Chris Dillow's Blog, page 21

May 26, 2020

Hoist by his own petard

There is genuine anger at the behaviour of Dominic Cummings not just among the usual suspects but among some Tory MPs such as Roger Gale and Douglas Ross. It's worth exploring why this should be the case.

It's because of cultural evolution. Early humans worked out (or stumbled upon) an important fact, that we often thrive best when we cooperate. As Axelrod and Hamilton showed in a classic paper (pdf):

Cooperation based on reciprocity can get started in a predominantly noncooperative world, can thrive in a variegated environment, and can defend itself once fully established.

Or as Ken Binmore put it in Natural Justice:

We don't need to pretend that we are all Dr Jekylls in order to explain how we manage to get on with each other fairly well most of the time. Even a society of Mr Hydes can eventually learn to coordinate on an efficient equilibrium in an indefinitely repeated game.

This cooperation takes the form of the Golden Rule, or do as you would be done by. As Binmore shows, pretty much all societies have some version of this principle. I agree to obey rules - even at a cost to myself - because I expect you to do so.

But how are such norms enforced? By punishing defectors, that's how. In Axelrod and Hamilton's formal scheme, this takes the form of tit-for-tat strategies. Less formally, we use mockery, ostracism and even violence: "snitches get stitches."

Most of us have internalized these norms. We know this from experiments with the ultimatum game, wherein one player is given some money and can split it with another, with the other choosing to accept or reject the offer. Purely selfish offerers would offer the lowest amount possible, and purely selfish receivers would accept. But this is not what happens. Offers of less than 30-40% are only occasionally made, and often rejected when they are.

This shows that we have a norm of fairness. Offerers don't make unfair offers even if they'd benefit from doing so, and receivers reject such offers even if they'd be financially better off accepting. Both sides do so because the norm of fairness over-rides short-term financial gains.

It's for a similar reason that people leave tips even in restaurants they'll not return to. We feel bad not tipping; we don't want to be thought badly of; and we want to uphold incentives for good service because we'd expect visitors to our regular restaurants to do the same for us.

This, I think explains the anger towards Cummings. It's because people think he has broken one of the oldest social norms, of thinking the rules that apply to us don't apply to him. Millennial of cultural evolution mean this norm is now viscerally internalized. Hence the power of the charge "one rule for them, one for us".

In this context, it is pointless to wiggle about claiming that Cummings observed the letter of the rules. Such legalistic pedantry misses the point - that it is the spirit of the rules that matter.

This also explains Conservatives' disquiet. Some of them genuinely believe in the rule of law - the principle that laws apply to us all, which is part of the Golden Rule. For them, Cummings has broken a core moral principle.

One irony here is that Cummings should have been aware of all this. As he himself wrote:

Most of our politics is still conducted with the morality and the language of the simple primitive hunter-gatherer tribe...Our ���chimp politics��� has an evolutionary logic: our powerful evolved instinct to conform to a group view is a flip-side of our evolved in-group solidarity.

Binmore points out that it was in tough times that norms of conformity were most strongly enforced, because it's then that survival requires them. Or as Marshall Sahlins put it:

During lean food seasons the incidence of generalized exchange should rise above average...Survival depends now upon a double-barrelled quickening of social solidarity and economic cooperation. The social and economic consolidation could conceivably progress to the maximum: normal reciprocal relations between households are suspended in favour of pooling of resources for the duration of emergency. (Stone Age Economics, p213-4)

Stone Age man's greater emphasis upon community and solidarity in hard times has a strong echo today. Because we're all suffering from the lockdown, we even more than usual expect everyone to muck in together and so are hostile to defectors.

But it has for decades had another echo. As Ben Friedman showed, in recessions we become more intolerant of outsiders, as solidarity with our tribe increases.

Which leads to an exquisite irony. Having exploited that atavistic sense of heightened solidarity so well during the Brexit campaign, Mr Cummings is now a victim of it. He is being hoist by his own petard. It takes a heart of stone not to laugh.

May 23, 2020

Austerity, power & BBC bias

George Osborne gave a revealing interview (1'52" in) to Radio 4 yesterday - revealing, not untypically for the BBC, for what it did not say.

Osborne said that sometime in the "next two or three years":

Markets, and indeed the country, will look to governments to set out plans for how they are going to eventually bring balance back to the public finances.

The first thing that was not said here - and certainly not by his fawning interviewer - is that the more educated parts of the country will be looking for no such thing. Intelligent economists (as well as me) agree that fiscal austerity will be counterproductive. With demand for gilts strong - even at negative yields - government borrowing is sustainable for now. And the best way to get it down is simply to ensure a strong economy. As Maynard Keynes said in 1933: "Look after the unemployment, and the Budget will look after itself."

Which poses the question. Why, then, would anybody prate about the need for austerity?

Which brings us to something else that was unsaid - that whilst austerity might not be technically necessary as a tool of macroeconomic management, it suits the interests of financial capital, a section of which pays Mr Osborne handsomely (another fact unsaid in the interview).

The reason for this is simple. For a given inflation target (the inflation target shouldn't be given but let that pass) monetary and fiscal policy are substitutes: tighter fiscal policy means looser monetary policy and vice versa. And this combination - what Osborne called fiscal conservatism and monetary activism - disproportionately benefits the finance sector for several reasons:

- Many trading strategies carry very low returns even when they pay off; various carry trades, arbitrage or near-arbitrage, or picking up pennies in front of steamrollers. To make them pay well requires leverage. Which needs cheap and easy money.

- Low interest rates and QE raise asset prices. And guess who benefits from these.

- As Costas Lapavitsas & Ivan Mendieta- Mu��oz show, bank profits depend a lot on the net interest margin. And this is often higher when banks' financing costs are lower. As Thomas Philippon and Guillaume Bazot have shown, the finance sector is oligopolistic, so lower costs don't get passed onto customers.

- Low interest rates encourage people to take on more debt, to the benefit of banks. They also encourage savers to "reach for yield" and thus entrust their money to high-charging fund managers. If annuity and savings rates were high, savers would be less inclined to buy expensive funds.

Whilst fiscal austerity doesn't serve the interests of the country as a whole, therefore, it does suit the finance sector.

And it has disproportionate influence over policy. We don't need conspiracy theories to appreciate this. Nor is it because the sector pays Mr Osborne's wages: he served its interests long before he entered its employ. Nor is it even because of direct lobbying, important as that is.

It's also because of what James Kwak calls "cognitive capture". Finance professionals enjoy undue influence because they are perceived to have high status and expertise and network with politicians and journalists. They thus benefit from both the mere exposure effect and from the fact that, as Adam Smith said, the "respectful attentions of the world [are] more strongly directed towards the rich and the great, than towards the wise and the virtuous.

Yet another mechanism of influence has been described by Timo Walter and Leon Wansleben. Policy-makers, they say, have been drawn into "a kind of ���ontological complicity��� with the dynamics of financialized capitalism" because large liquid markets give central banks more means of influencing the economy and hence greater power.

In these ways, financialization is self-reinforcing: a bigger financial sector gives finance greater pwoer.

Which is why I say that interview with Osborne was so inadvertently revealing. The (one-sided) discussion was framed in terms of what seems best for the country as a whole. But this of course is a fiction. Policy-making is not a technocratic exercise in what is best for the country but rather a matter of the extent to which policy is constrained by the influence of capital.

But how does that influence operate? How strong is it? Whose interests therefore does policy serve? These are questions which BBC usually overlooks. Which means that it is systematically and dangerously biased.

May 19, 2020

What we don't see

Daniel Hannan recently tweeted:

Around 80% of us say we support the lockdown. But, looking around me, I���d say that no more than 20% are still observing it rigorously. Is this a case of what economists call ���revealed preference��� - or do people want everyone else to apply stricter rules than they do themselves?

It might well be neither. Instead, it���s an example of the sampling bias. The people we see are, by definition, those who are outdoors and thus who are disproportionately likely to be breaching the lockdown. What Mr Hannan isn���t seeing are the countless thousands of us staying indoors and observing the lockdown. He���s failing to appreciate that what he sees is a biased sample of what there is.

In fairness to him, this is a common error, as experiments by Benjamin Enke have demonstrated. Here are a few other disparate examples of a similar mistake.

Benefit fraud. People greatly over-estimate the extent of this. A survey by the TUC a few years ago found that ���people think that 27 per cent of the welfare budget is claimed fraudulently, while the government's own figure is 0.7 per cent.��� One reason they do this is that they can see fraudsters whereas they don���t see the millions trapped indoors by disability or depression.

Opportunity cost. As Frederic Bastiat pointed out, we see the shopkeeper spending money to replace his broken window but don���t see that he would have spent money elsewhere had his window not been broken. We thus wrongly infer that some activities ��� be it breaking windows or going to war ��� boost economic activity when in fact they often don���t.

The unseen counterfactual. Because we don���t see the road not taken, we don���t benefit from the Jim Bowen effect: ���here���s what you could have won.��� We don���t therefore blame governments sufficiently for policies which impoverish us relative to a plausible counterfactual ��� such as austerity or Brexit.

Social transmission bias. In a recent paper David Hirshleifer describes how people���s savings and investment decisions are distorted by the biased signals they get from others. Because people are more likely to discuss their successes than their failures, they talk more about low-return but high-risk strategies that happened to get lucky. This leads listeners to believe that stock-picking works better than tracker funds and that speculative shares pay off better than defensive ones when in fact (pdf) they generally don���t.

Survivorship bias. The shares that are listed on the stock market are by definition those that have not gone bust. They are therefore a biased sample of all stocks. Because investors don���t fully appreciate this bias, they under-estimate the chances of corporate failure, especially over the long-run, and so over-estimate their chances of picking good stocks. In fact, as Hendrik Bessembinder shows, most stocks actually lose money over their lifetime, and stock market rises are due to great performance by a tiny minority of shares.

Biased news. As the ancient saying goes, ������dog bites man��� is not a story but ���man bites dog��� is���. What we see reported on the TV are, therefore, unusual events. But by definition these do not describe reality. It���s partly for this reason that the fear of crime has not fallen as much as actual crime has. Also, in reporting salient events, the news understates slow-moving but world-changing trends ��� be it the decline in global poverty, stagnation in productivity or long-term decline in government borrowing costs. In this sense, the news ��� even if presented wholly honestly ��� distorts our perceptions of reality.

Immigration. People see what they think to be an adverse effect of immigration: ���some immigrants arrived a few years ago and I���ve lost my job since.��� What they don���t see, however, are the many mechanisms which counteract this apparent effect.

And herein lies the point. The social sciences are, as Jon Elster said, fundamentally a collection of mechanisms. But many of these are unseen. It is the role of social science to expose these mechanisms, and to show us that what we see is not all there is. As Marx said: "If there were no difference between essence and appearance, there would be no need for science." Or as Marvin Gaye, another great social thinker, famously put it: ���believe half of what you see and none of what you hear.��� Mr Hannan could learn something from him.

May 14, 2020

How to be wrong

���The tradition of all dead generations weighs like a nightmare on the brains of the living.��� I was reminded of these words of Marx by the Telegraph���s report that some Treasury officials are pushing for tax rises and spending cuts in part because there is a ���plausible��� risk of a sovereign debt crisis.

Of course, Simon is right: there is no such risk as the Bank of England can, in extremis, buy up gilts. Certainly, financial markets aren���t worried; the latest gilt auction saw record demand. And it would be foolish to begin austerity before the recovery is well-established.

Which only poses the question: why do intelligent people believe such silly things?

Part of the answer lies in selection effects. The interests of capital constrain policy options, and the rise of financial/rentier capital and decline of Fordist capital has increased pressure for easier monetary policy rather than looser fiscal policy.

This is compounded by the fact that the marketplace in ideas is failing. John Stuart Mill thought that ���wrong opinions and practices gradually yield to fact and argument���. But for various reasons ��� not least being our media ��� this does not happen. Nick Robinson���s claim on the Today programme yesterday that "the money has to be paid back somehow" shows that the myth of the government as a household stays obstinately alive.

But there���s more to it than this. There are also powerful psychological mechanisms that cause the Treasury���s error ��� mechanisms which, of course, occur all the time in other contexts. Here are three.

Formative years.

Napoleon was right: ���to understand the man you have to know what was happening in the world when he was twenty.��� Those of us in our 50s remember talk of the government having to go ���cap in hand to the IMF���. And we were educated at a time when real interest rates were high and so we thought fiscal policy was constrained both by the fact that high yields would cause debt to increase and by the danger that borrowing would raise interest rates and so crowd out private sector spending. Of course, we now live in a completely different world of a savings glut, negative real rates and dearth of investment. But it���s hard for our minds to fully adapt. Marx was right; they are shaped by the past, not just the present.

We have good empirical evidence here from another context. Erin McGuire and Ulrike Malmendier (pdf) have both shown that our attitudes are disproportionately shaped by how the economy appeared to us in our formative years. People who suffered hard times, they show, invest less in equities even decades later. The distant past thus unduly influences behaviour today.

Bayesian conservatism.

We hate admitting that we were wrong. We therefore stick to our prior beliefs more than we should. If you sympathised with post-2010 austerity, therefore, it���s hard to admit you were wrong even in the face of strong evidence.

Again, it���s not just Treasury officials, journalists and politicians who make this error. People make the same mistake even when there is big money at stake. One of the strongest tendencies in equity investment is the so-called disposition effect; people hold onto badly performing shares because selling them would mean admitting ��� if only to themselves ��� that they were wrong.

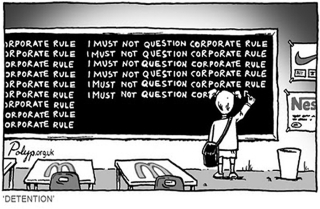

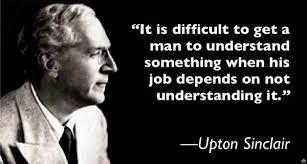

Deformation professionelle.

Our professional training doesn���t just give us skills. It also inculcates particular biases into us ��� ways of seeing the world which are only partial. For decades, the Treasury���s role has been to watch the pennies ��� and in fairness somebody has to. This can easily lead to the belief that the pennies must be watched even when thy don���t need to be ��� a tendency reinforced by bureaucrat���s habit of mistaking bureaucratic convention for objective reality. And it is further reinforced by our reluctance to abandon ideas on which our career is built. As Upton Sinclair said, ���It is difficult to get a man to understand something, when his job depends on not understanding it.��� We apply the sunk cost fallacy to our beliefs.

Again, though, Treasury officials are not unusual here. Economists tend to over-estimate the role of financial incentives; lawyers over-estimate the role of the law as an agent for addressing social problems; and as for engineers���(pdf).

My point here is that it is incredibly easy to be wrong. The three mechanisms I���ve described here are powerful and ubiquitous. You can no doubt think of many other ways in which they apply ��� not least to me. This makes it all the more important that in politics we have filtering mechanisms which weed out errors. Our problem is that not only do we not have such mechanisms but that too often we have the opposite ��� ones that select not against error but in favour of it.

May 6, 2020

Technocrats & class

Are centrists even more utopian than socialists? I���m prompted to ask by a passage at the end of Anne Case and Angus Deaton���s Deaths of Despair. They write:

We believe that capitalism is an immensely powerful force for progress and for good, but it needs to serve people and not have people serve it. Capitalism needs to be better monitored and regulated, not to be replaced by some fantastical socialist utopia.

This comes after 260 pages in which they document how American capitalism has recently been a force not for progress and for good, but for mass social murder. They describe how the collapse of demand for unskilled labour has caused ���the loss of meaning, of dignity, of pride, and of self-respect��� and so led to tens of thousands of needless deaths of despair among the white working class ��� from suicide, alcoholism and drug abuse. The pharmaceuticals industry, they say, is ���profiting by destroying lives��� ��� not only through its over-prescription of opiods but because in forcing up the cost of health insurance it prices the low-paid out of the labour market.

How, then, can they believe in the face of their own evidence that capitalism is a force for good?

The answer is that centrists are prone to a form of utopianism, of wishful thinking.

They believe that reasonable policies and institutions could constrain capitalism���s rapacious and murderous tendencies and so make it a force for good. What this fails to see is that the same rapacity that makes capitalism a force for bad also forbids such change. Any child could think of a better healthcare system than the US���s; just look at any other advanced country. The US does not have such a system not because of a lack of intellect but because of the power of capital. As Case and Deaton show, the healthcare industry spends over ��500bn on lobbying, and employs five lobbyists for every one Congressman.

Lobbying, though, is only one of several levers that capital has over the state. The prospect of well-paid jobs after they leave politics incentivizes politicians to do capitalists��� bidding whilst in office. Blackrock isn���t paying George Osborne a fortune for his expertise; it is doing so to show finance minsters around the world the rewards of playing by the rules.

There���s also ideology. Capitalism (or indeed any social system) endogenously generates beliefs which help sustain its power structures, a process reinforced by the media: John Jost calls this system justification (pdf).

And then there���s plain deference. As Adam Smith wrote:

We frequently see the respectful attentions of the world more strongly directed towards the rich and the great, than towards the wise and the virtuous

And of course, there are also economic levers. Governments feel the need to preserve business confidence in order to create jobs, which of course constrains its policy-making.

Given all these channels, a finding (pdf) by Martin Gilens and Benjamin I. Page should not surprise us:

Economic elites and organized groups representing business interests have substantial independent impacts on U.S. government policy, while average citizens and mass-based interest groups have little or no independent influence

Pablo Torija Jimenez shows that this is true in most developed economies.

The power of capital over the state has not always been so malign. In the three decades after WWII, there was good evidence for Deaton and Case���s faith. Capitalism did indeed deliver full employment and rising wages, and there was a modicum of equality: the share of US incomes going to the 1% was barely half what it is today.

The Golden Age of capitalism was not, however, the product of mere goodwill. It was the result of material interests. Fordist capitalism required domestic mass markets, which required highish wages and full employment. And the threat of communism forced capitalists to prevent discontent. Yes, the US never had a large socialist party. But it did once have something nearly as good - a fear of socialism. Capitalism was kept tolerably decent by what j.K. Galbraith called countervailing powers.

Today, though, this has changed. Capitalism has become more extractive and financialized, requiring high margins and cheap money more than mass markets. General Motors needed a large well-paid working class; Goldman Sachs, not so much.

The murderous power of the US healthcare industry and the vote for Brexit are both, in their different ways, signs of the victory of regressive capital.

Today���s capitalism, then, rules out the humane policies favoured by Case and Deaton, and thus refutes their optimism. Jeremy Cliffe recently asked ���why the Anglo-Saxon model keeps going so wrong.��� It���s because the dominance of extractive capitalism over the state precludes good technocratic politics.

In saying this, I am not making an original point. I���m merely echoing what Kalecki said (pdf) in 1943. He noted that economists knew technically how to achieve full employment, but feared that capitalists would oppose such policies:

The maintenance of full employment would cause social and political changes which would give a new impetus to the opposition of the business leaders. Indeed, under a regime of permanent full employment, the 'sack' would cease to play its role as a disciplinary measure. The social position of the boss would be undermined, and the self-assurance and class-consciousness of the working class would grow������Discipline in the factories' and 'political stability' are more appreciated than profits by business leaders. Their class instinct tells them that lasting full employment is unsound from their point of view, and that unemployment is an integral part of the 'normal' capitalist system.

���The assumption that a government will maintain full employment in a capitalist economy if it only knows how to do it is fallacious��� he said.

Granted, he was wrong for 30 years after writing that. But the point is bang on today. Which is why Case and Deaton are missing something important. Good policy doesn���t require merely technical know-how. It requires the right material conditions, the right power bases. It is these, rather than technical know-how, that are lacking.

Case and Deaton are of course not alone in this error. Let���s take just two recent examples, though you can no doubt think of many more. Layla Moran calls for a universal basic income. Such an income ��� if meaningful ��� would empower workers to reject bad jobs. But Ms Moran does not ask whether this is compatible with an extractive capitalism which wants a mass supply of cheap and quiescent labour. And Nick Cohen rightly lambasts our government of charlatans and dilletantes without asking whether this is the product not merely of individual bad character but rather of the nature of British capitalism: it prefers incompetents to anybody who challenges the system.

But why is the error so common among highly intelligent people?

I suspect what we have here is an example of schools functioning inadvertently as what Louis Althusser called ideological state apparatuses. At impressionable ages we are brought up to believe that success comes from knowledge and intellect. We thus believe this even in contexts where it is wrong. We���d be better prepared for politics if teachers gave top marks not to the brightest students but to the school bullies.

It���s in this context that many of us applaud Corbynism. It mobilised an albeit-modest countervailing force to extractive capitalism ��� a base of renters, public sector workers and immaterial labour. Whilst this wasn���t sufficient for electoral victory, it did help pressurize the government into relaxing austerity.

The left realized that good, sensible decent technocratic policies require not just expertise but a material base in the form of particular types of class power and interests. And in the UK and US, this base is missing. In failing to realize this, centrists are too na��ve.

April 29, 2020

Avoidable unemployment

We Marxists are often accused of being ideologues. This is silly. Everybody has an ideology, in the sense of a set of preconceptions about how the world works. The difference between we Marxists and others is that we are sufficiently self-aware to know this. By contrast, some of the most dangerous ideologies are those which their believers take for granted despite being wrong. This, I suspect, helps explain what is otherwise a paradox.

The paradox is that most voters approve of the government���s handling of the coronavirus crisis despite the fact that Universal Credit claims show that unemployment is soaring, especially perhaps among freelancers: the ONS expects (pdf) it to rise by two million, to over 10 per cent of the workforce.

This rise, though, is largely preventable. In principle, the government could protect jobs and income via tax rebates or debt interest or rent holidays. Of course, the lockdown means that output and incomes must fall. But in principle, all of this fall could be borne by the public finances, leaving firms and individuals cocooned.

Now, there is a case against doing this, as Giles Wilkes has shown. Protecting firms in this manner would mean bailing out firms that would have gone bust anyway: many retailers and restaurants were failing before Covid-19 struck.

Giles has a point. Economic growth requires creative destruction: one reason (of many) for our stagnant productivity since the financial crisis has been that zombie firms have blocked the growth of more efficient ones, as weeds prevent desirable plants from growing.

What���s true in normal times, however, is not necessarily true in crises. Right now, the best-run restaurants and non-essential retailers are seeing exactly the same collapse in demand as the worst ones. What determines their survival chances is not so much their efficiency as their balance sheets: cash-rich firms have better survival chances than indebted ones. But the correlation between efficiency and balance sheet strength might not be high: a firm can have high debt because it has been badly managed, but it could also be because it is a well-run outfit that had sensible expansion plans. Letting market forces work now would not, therefore, necessarily see the survival of the fittest.

What���s more, we need creative destruction in normal times so that the resources released by failing firms can go to more efficient ones. But this won���t happen when even efficient firms are locked down. So there���s no economic benefit from letting firms fail now. There is however a massive psychological cost. Even in the best of times, unemployment (pdf) is a huge source of misery. To force people out of work when they have no immediate hope of finding another job would be an act of cruelty.

For these reasons, I think firms should be supported now. The time to let creative destruction rip is when aggregate demand has recovered. Giles is right to say this will require a huge and difficult pivot. But it should be tomorrow���s problem, not today���s.

Whatever its merits, though, Giles��� argument, however, does not explain why the public are so accepting of soaring unemployment: voters don���t really support a free market economy, and certainly not the chill winds of creative destruction.

Instead, I suspect this tolerance reflects an often-implicit ideology, which rests upon two related errors. One, which I���ve described earlier is that people often conflate costs with what are in fact transfers. Journalists speak of the ���cost��� of the Job Retention Scheme when what they really mean is the size of the transfer. In fact, it is wrong to speak even of this as a ���cost��� to the Exchequer. It���s plausible that preserving jobs today will permit a stronger expansion in future ��� for example, by preserving valuable matching capital; maintaining capacity thereby reducing the inflation constraint on growth; or by mitigating scarring effects upon animal spirits. If so, the Exchequer will gain future tax revenue.

This error is especially nasty when combined with another one ��� the tendency to think of the government finances as being like a household���s. Because we as consumers cannot afford some things, we infer that governments cannot afford them either, and so consider it impossibly expensive for the government to fully cocoon the economy.

Of course, as sensible economists have pointed out for ages, this is plain wrong. We can print money to buy increased government debt. The only constraint on government borrowing is inflation. And you don���t fight inflation tomorrow by destroying economic capacity today.

As I say, the cost error and the government-as-household error are often only implicit in most voters��� minds. But they have been reinforced down the years every time an interviewer asks ���where will the money come from?��� and confuses costs with transfers.

For many, ideology, like culture, is ���everything you don���t notice��� ��� and, therefore, what you don���t question. Every economist knows that the government-as-household metaphor is gibbering imbecility, but it has been implicit and unquestioned in the media and in voters��� minds.

This leads to a version of what Georg Lukacs called reification. Although the economy is a set of relationships between people and therefore something which we should be able to control, people come to see it as an external force which governs us because they under-estimate (often unconsciously) the amount that governments can do. As Lukacs put it:

A relation between people takes on the character of a thing and thus acquires a ���phantom objectivity���, an autonomy that seems so strictly rational and all-embracing as to conceal every trace of its fundamental nature: the relation between people.

Rising unemployment is thus seen as a natural disaster rather than what it is - a man-made catastrophe. And so the government escapes blame.

April 24, 2020

Risk in capitalism

One thing this crisis is demonstrating is that in modern capitalism it is workers and small businesses that bear risk to a greater extent that does larger capital.

As Paul Evans points out, some of the biggest losers are freelance workers who are ineligible for furlough schemes. And Charles Gascon at the St Louis Fed adds that it is low-paid workers who are most at risk of losing their jobs:

The occupations at the highest risk of unemployment also tend to be lower-paid occupations. The average annual earnings of the low-risk occupations is $64,600, about 75% higher than earnings in the high-risk occupations, at $36,600. This indicates the economic burden from this health crisis will most directly affect those workers who are likely in the most vulnerable financial situation.

The UK is unlikely to be much different.

By contrast, most asset-owners could with only moderate care have avoided big losses; in the IC, I���ve shown that simple diversified portfolios have lost only tiny sums.

This contrast is the culmination of several long-term trends which have seen capital de-risk in recent years at the expense of workers. For example:

- The shift to a two-tier workforce with a core of staff and periphery of gig workers and freelancers means that companies can more easily shift cyclical risk onto workers. As Paul says, firms have ���managed to shovel all of the risk related to their industry down the pipe to freelancers.���

- Some workers are now in fact capitalists in the sense that they supply capital ��� for example freelance sound mixers supply their own expensive kit; Uber drivers take on debt to supply cabs; and some delivery drivers must supply their own vans and uniform. This exposes them not just to ordinary job risks, but also to the dangers of losing a capital investment.

- Some capitalists make themselves secured creditors which means they lose little when ���their��� business fails, whilst the cost falls upon workers and subcontractors ��� as we saw, for example, with the collapse of Carillion.

- As Rene Stulz and Kathleen Kahle have shown, stock market listed companies have become older, bigger and more cash-rich in recent years: this is true of the UK as well as US. This means the typical equity investment is less risky than it used to be.

- The closure of final salary schemes means that the investment risk involved in saving for retirement has been transferred from firms to workers, even though they are unable to carry such risk efficiently.

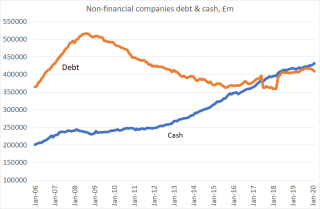

- UK companies generally have derisked their balance sheets since the financial crisis. Bank of England data show that their (sterling) cash holdings have doubled since then, and that non-financial firms now hold more cash than debt. (This is partly a reflection of the growing importance of intangible assets, though whether these are any riskier than tangible assets such as machinery is moot.)

- The shift towards monetary activism and fiscal conservatism tends to benefit asset holders (especially leveraged ones) more than workers, as asset prices benefit from low interest rates and QE.

Now, this is not to pretend that there was a golden era in which workers had security whilst capitalists did not. As Judy Stephenson reminds us, piece-work is as old as capitalism and was one way in which capital transferred risk to labour. Nevertheless, it is the case that recent trends have been for larger capital to transfer risk to workers, subcontractors and smaller firms. The idea that the boss of a large firm is a swashbuckling risk-taker is a fiction as great as any portrayed in Hollywood, as Olivier Fournout has shown.

This raises two questions. One is: what function, then, do capitalists fulfil?

It is certainly not the provision of finance capital. Governments can do this cheaper and in greater abundance, as Rishi Sunak implicitly acknowledged this week with his plan to support innovative businesses. Nor is it clear that they effectively finance smaller firms. The stock of UK bank lending to manufacturing SMEs is a mere 9.4bn. That means that for every pound banks have lent to small manufacturers they have lent ��155 in mortgages on houses.

Instead, increasingly, capitalists simply supply platforms. They act as middlemen connecting workers to other workers and to customers.

A second question this poses is: who should own firms? Common sense says that owners should be those with the most skin in the game. If you have most to lose from a firm going bust you have the biggest incentive to ensure that it doesn���t. This points to a case for subcontractors, freelancers and workers to have equity stakes ��� especially to the extent that they supply firm-specific capital and skills. As it is, current ownership structures give big capital exposure to upside risk whilst its workers and freelancers who face the most downside risk.

What we have here might yet another example of how ideas can outlive their evidence base. We still think of capitalists as like Victorian mill-owners who face the risk of ruin if their investments fail, and so are entitled to ownership and rewards on that account. But this is no longer the case. We must ask: what exactly is it that capitalists do and does this justify ��� even on narrow grounds of efficiency ��� their ownership?

April 16, 2020

When rules don't apply

It���s a clich�� that this is a crisis. But what exactly is a crisis? I like Richard Bookstaber���s idea ��� that it is a time when normal economic rules don���t apply.

For example, in normal times investors can reasonably think about valuations and corporate earnings. But in crises what matters instead is risk and liquidity. In normal times, negative feedback loops dominate: cheap assets will rise in price. But in crises, there���s a heightened danger of positive feedback whereby selling begets more selling.

In the 2008 crisis, for example, some opposed bank bailouts fearing a moral hazard problem. But they were applying normal times thinking. What mattered much more was keeping the financial system alive.

We���re seeing the same thing now. This crisis means that some normal ideas don���t apply. Here are five.

1. Robert Peston asks whether the furlough scheme is destroying work incentives. He���s not alone. Universal Credit was designed to incentivize work, by making the application process complicated; by ensuring a long wait between application and payment; and by keeping unemployment benefits low.

But this is not the issue now. Quite the opposite. We actually want to disincentivize work, to ensure that people don���t spread the virus.

2. Fiscal rules might be needed in normal times. But we don���t need them now. The same crisis that is raising government debt is also increasing demand for safe assets. This is why gilt yields have fallen this year despite the OBR���s forecast (pdf) that the crisis will add ��429bn to public deby by 2021.

3. In normal times we should worry about allocative efficiency, and not bail out lame duck companies. In this crisis, however, this concern is a low priority. James Tobin���s famous remark is more true than ever: ���it takes a heap of Harberger triangles to fill an Okun gap.���

4. Economic forecasts are sometimes useful ��� although as Prakash Loungani has been saying for years they always fail to foresee recessions in time. But they���re not so much now. We know that economic activity is plummeting and that unemployment is soaring. But we cannot know the magnitudes and do not need to. If I were to say that GDP will drop 10 per cent this year rather than 15, it would be daft to infer that we should support the economy less. 10 per cent is still a lot. And given the uncertainty around it, we should err on giving maximum support. If a man if falling from a plane, he doesn���t need to know at what speed he���ll hit the ground: he needs to know how to open a parachute.

5. Ordinarily, we should worry about the distributional impact of support packages, incentive effects and whether systems will be gamed. In a crisis, though, these are low priorities. What matters, as Eric says, is that the support be immediate and large. If your house is on fire, you should not worry about your carpets getting wet. You should put the fire out and clean up the mess later.

Our priority must be to protect valuable economic assets. This means protecting jobs, because unemployment is a source of much misery. It also means protecting companies, because organizational capital and firm-specific human capital are valuable assets. Contrary to the simple-minded Econ-101ers, capital and labour are not fungible.

Yes, supporting firms means keeping some lame ducks in business, such as the many mediocre retailers and restaurants that would have gone bust even if the virus had not struck. But If they are to go bust, let���s have them do so during the recovery, when their labour and assets can be hired by expanding firms.

And there���s tons more the government can do. It could give tax rebates to firms and the self-employed. It could give rent holidays: unlike workers and firms landlords don���t (for the most part) provide useful assets and so should be a low priority for support. And it could also provide loan repayment holidays too, if necessary by taking a bigger place in banks��� capital structures. In this sense, Sunak���s support does not go far enough: the fact that Universal Credit applications are soaring tells us as much.

In ordinary times, these would not be great ideas, and they'd have to be reversed in the upturn. But these are not ordinary times. And we must all be intellectually flexible enough to spot the difference.

April 12, 2020

What centre?

The election of Keir Starmer as Labour leader has caused some leftists to fear that the party will move to the centre. Such fears, though, miss the point ��� that there is no centre.

By this I don���t just mean that there are no votes there, as the LibDems and CUK (or whatever they called themselves) discovered in December. I also mean that there are no ideas there either. One feature of CUK was its utter lack of economic thinking and obliviousness to the fact that the economy has changed a lot since the 90s and so requires new policies. Almost the only substantive thought in its launch document was the notion that government has a ���responsibility to ensure the sound stewardship of taxpayer���s money��� ��� an idea that has aged as well as Rachel Reeves desire to be tough on the unemployed.

But this poses a question. Is this vacuity due merely to the inadequacy of centrist politicians? Or does it instead reflect capitalist reality?

To see what I mean, think about two contrasting ideal types of capitalism. Type one relies for its profits on a mass market in consumer goods produced by skilled workers. It has significant profit opportunities but faces a consistent risk of unforeseeable recessions. And it also faces the danger of a socialist uprising.

This type of capitalism would welcome a centrist agenda of Moderate Progress Within the Bounds of Capitalism. Policies to underpin wages would help sustain demand and profits. A decent welfare state acts as an automatic stabilizer, thus reducing capitalists��� risk of recession. The need for skilled workers means capitalists welcome public spending on education and science. High profits mean some redistribution is tolerable ��� and, indeed, necessary given the need to buy off discontent and so prevent socialism.

In such an environment, there���s plenty centrists can do to ameliorate the worst effects of capitalism whilst respecting the power structures of the system. Centrism should then be healthy.

Imagine instead a very different type of capitalism. Here, capitalists believe they need not a mass market but policies to increase profit margins, and so need profit-led rather than wage-led growth. It also has low profits and few profit opportunities and so resists more fiercely higher taxes, and is less supportive of expansionary macroeconomic policies that might empower workers. Facing no threat of revolution, it has less need to buy off discontent. Being more dependent on unskilled workers it needs guard labour and surveillance methods more than skills. And having a large finance and rentier sector it needs to protect its methods of extracting surplus more than means of expanding real capital. And that same financialization means it wants not a large welfare state and automatic stabilizers but simply looser monetary policy.

In this world, there���s much less room for centrist reforms. Capitalists will protect their own power and extractive institutions whilst socialists will want more radical change than centrists can stomach.

Of course, I���m talking ideal types here. Actually-existing capitalism is an admixture of the two ��� although post-war Fordism was close to type one. But there can be little doubt that British capitalism has shifted from type one towards type two. Hence the decline of centrism; there���s just no space for it.

This is not to say that there are no centrist ideas at all. I commend Sam Bowman and Stian Westlake and the Radix thinktank. Several of their ideas, however, would face strong opposition from vested interests ��� for example, the proposals to cap CEO pay, regulate finance more strongly, or introduce a land value tax.

We can imagine a world in which such opposition would be offset by support from a client base within capitalism. Type one capitalists would welcome a shift in taxes from profits onto landlords and curbs upon financial extraction: if you want to hear extreme hostility to bankers, don���t speak to me or Grace Blakeley, just ask anyone running a manufacturing business. The influence of this client base is, however, weak: the vote for Brexit told us that.

A better base for challenging this type of capitalism, therefore, is to have a large clientele opposed to the interests of rentiers and with an interest in radical reform. Corbynism activated just such a base, and it shouldn���t go away.

I���m not, therefore, very worried that Starmer can shift Labour to the centre on economics, even if he wanted to. There is no meaningful, viable centre.

Instead, I have a different concern. The media ��� including the BBC ��� is creating a climate which rules out questioning of the Dear Leader and which regards measures to support economic activity as a cost rather than benefit. I fear that Labour will become infected by this poison. Which is why we desperately need a counterweight in the form of leftist critiques of the media ��� to remind Starmer that he need not be swayed by it.

There might be no intellectual pressure on Labour to shift to the centre. But it could drift there simply under media influence. Corbynistas, then, should not keep quiet.

April 7, 2020

"We've established that, madam"

George Bernard Shaw, it is said, once met an actress and asked her: ���would you sleep with me for a million pounds?��� ���I would think about it��� she replied. ���Would you sleep with me for a pound?��� he then asked. ���No��� she replied. ���What sort of woman do you think I am?��� He replied: ���We���ve established that, madam. Now we are haggling about the price.���

We should thing about policies the same way. Sometimes, it is worth establishing the principle, and then haggle about magnitudes and timing.

For example, New Labour introduced the minimum wage at a derisorily low rate in 1999. But having established the principle of a minimum it was easy to raise it, and so the UK���s minimum is now comparable to those of many other nations. Similarly, Thatcher���s privatizations began as a small-scale attempt to reduce government borrowing, but they quickly scaled up. In the same vein, this is why so many of us on the left have zero tolerance for racist or anti-immigration rhetoric and why we were repulsed by Ed Miliband���s ���controls on immigration��� mug. Once such discourse becomes acceptable, it leads to the hostile environment policy and the Windrush disgrace.

It���s from this perspective that we should regard debates about the policy response to Covid-19. It���s an opportunity to ���establish that, madam��� ��� to create a consensus for policy principles which we can expand or refine later.

In the case of fiscal policy, this has already happened. In borrowing to subsidize wages among other things, Rishi Sunak has established that the UK has abundant fiscal space and that the notion that there is a binding limit on the ���nation���s credit card��� is nonsense. As Eric says, austerity was a ���fraud.���

Similarly, Spain is introducing something like a basic income. Whilst purists might worry that it is not as universal or unconditional as a true UBI, I���m not sure this much matters for now, What does matter is establishing the principle. Once a policy is in place, even in mild form, we have overcome a huge obstacle - the status quo bias. It is much easier to reform than to introduce.

A lot else, though is up for grabs. One reason why so many Germans are opposed to the idea of coronabonds is that they would establish the principle of a euro-wide backed bond and so be a stepping stone to a fuller fiscal union and to fiscal transfers. Which of course is why so many others are pushing the idea.

Also, one thing this crisis has taught us is that we need in place the infrastructure to give support to people quickly. In this regard, whilst the current depression is almost unprecedented in speed and severity, it is not unprecedented in being unpredictable. As Prakash Loungani has shown, mainstream economists and policy-makers have failed to foresee almost all recessions. Which means that monetary and fiscal policies which operate on demand with a lag are insufficient: they might moderate the downturn and accelerate the upturn, but they can���t prevent the downturn. Hence the need for automatic stabilizers.

What I���m arguing for here is to seize the moment, to use this crisis to establish policies and institutions that are hard to reverse. Many of you think this crisis will change public opinion in favour of redistribution and greater public spending. I���ve no such confidence. We tend to project (pdf) our current preferences too much into the future and fail to see that they���ll change. We cannot, then, rely upon the public mood staying as it is.

In this sense, I���ve mixed feelings about Frances��� claim that now is not the time for a universal basic income or helicopter money. She might be right speaking of them as technical fixes, but now is the time to establish the case for them in principle, and to lay down the plumbing to enable them to work ��� such as, for example, ensuring that everybody has a bank account.

Much of what I���m saying here might seem obvious, even cliched. ���Thin end of the wedge��� and ���slippery slope��� have long been conservative objections to mild social reform.

But I���m not sure it is. What I���m saying here contradicts some common views of policies. Technocrats see them as fixes of current problems whilst some na��ve leftists always complain of their inadequacy. What both perspectives miss is that policy-making is not merely an engineering matter of pulling levers and fixing things. Even apparently mild policies can lead to bigger things.

We must always ask, therefore of any policy: where will this lead? Sometimes, it opens a door to further change ��� as with the NMW. At other times, though, it can be a dead end. New Labour���s increases in public spending died with its electoral defeat, whilst its embrace of new public management (pdf) alienated many traditional Labour supporters and failed to increase public sector productivity.

But of course, policy doesn���t merely change the intellectual climate. It also changes the material base of support for future policy change. Thatcher, for example, both destroyed the unions and ��� via expanding the financial sector and selling off council housing - enlarged the client base for financialization. And in expanding universities, New Labour expanded the cohort of immaterial labour with a globalist outlook: it was Blair who laid the foundations for Corbyn.

My point here is a simple one that���s often overlooked. Policy-making is a dynamic, not a static process. It is not merely a matter of getting the right technocratic fixes.

Chris Dillow's Blog

- Chris Dillow's profile

- 2 followers