Chris Dillow's Blog, page 18

August 28, 2020

Tories against Thatcher

Be careful what you wish for. This old saying applies to us lefties. For years, we���ve wanted to see the end of Thatcherism. And we���ve now got it. And it���s an ugly sight.

I say this because of Johnson���s campaign to end working from home and get us back into the office. This is anti-Thatcherite in two senses.

For one thing, Johnson is contradicting two of Thatcher���s favourite principles ��� that ���you can���t buck the market��� and that managers have a right to manage. Many big employers are happy for staff to continue working from home. So why should the government say otherwise? Ryan Bourne expresses the spirit of Thatcherism when he says it is ���quite frankly none of the govt���s business��� to tell us what we should be doing.

Also, Johnson is motivated by a fear that city centres are becoming ghost towns. Thatcher, however, was content for large areas of the country ��� mining towns ��� to meet this fate. She thought that miners could move to better jobs. A genuine Thatcherite would think the same should be true of sandwich makers.

These, however, are not the only differences between Johnsonism and Thatcherism. There are others, even if we disregard the massive increase in state intervention triggered by Covid-19.

First, Thatcher placed great emphasis upon the importance of stability, believing this to be necessary to help businesses plan and invest:

An economy will work best when it is built on a framework of clear and predictable rules on which individuals and companies can depend when making their own plans. Government's primary economic task is to frame and enforce such rules.

Today���s Tories, by contrast preside over huge and continued instability. Since the start of 2016 policy uncertainty, as measured by Baker, Bloom and Davis, has averaged twice as much as it did from 1998 to 2015.

Secondly, Thatcher was an architect of the single market, which she saw as ���a fantastic prospect for our industry and commerce!��� which offered ���complete freedom for our manufacturers, our road hauliers, our banks, our insurance firms, our professions to compete.��� Johnson, of course, is destroying that achievement. And whereas Thatcher wanted to cut red tape, Johnson is imposing it at a cost of billions. Johnson once said ���fuck business��� ��� a sentiment as far from Thatcherism as you can get.

Thirdly, Thatcherism was in many ways a modernising project. She wanted to modernise industry by removing over-manning and restrictive practices ��� which she did in the nationalized industries before selling them, as David Edgerton points out in The Rise and Fall of the British Nation. She attacked Labour for wanting to ���put back the clock��� whilst celebrating ���the wealth creators, the scientists, the engineers, the designers, the managers, the inventors���all those on whom we rely to create the industries and jobs of the future.���

Today���s Tories, by contrast, offer no such modernising project. Instead, their vision is an atavistic yearning for an imagined past. Whereas Thatcher offered young people hope ��� not least the hope of owning their own home - today���s Tories do not. Yes Thatcher wanted to achieve cultural change, but she saw economics as the means of achieving that.

Hence another stark difference between Thatcher and Johnson. Thatcherism was popular with young people. In the 1987 election, the Tories beat Labour by 39-33% among 25-34 year olds. In the 2019 election, they trailed massively. Thatcher created from young graduates a bunch of shoulder-padded, big-haired, champagne-swilling yuppies. From the same material, the Tories now have created a mass of discontent.

In all these respects, the Tory party is now fundamentally anti-Thatcherite. In one sense, it has to be, as Thatcherism failed, and not just because it ran out of other people's assets to sell.

And yet for all its intellectual revolutions the Tory party is still the Tory party. Just as Trigger���s broom had 17 new heads and 14 new handles but stayed the same, so the Tory party is still the Tory party. So where���s the consistency?

It lies, I suspect in the reason why Johnson wants to get us back to the office. It���s not because he cares about sandwich shop workers (many of whom are migrants) but because he���s worried about the landlords of office blocks. As Marx said in 1852:

The Tories in England long imagined that they were enthusiastic about monarchy, the church, and the beauties of the old English Constitution, until the day of danger wrung from them the confession that they are enthusiastic only about ground rent.

August 26, 2020

The politics of life & death

What, if anything, is wrong with the Kaldor-Hicks principle? This is the question raised by Chris Whitty���s argument that the benefits of reopening schools outweigh the costs of doing so.

Even if we suppose that this is factually correct - which it might not be ��� it does not follow that it is right to reopen schools. As David Hume said, we cannot derive ���ought��� from ���is���.

Which is where the Kaldor-Hicks principle comes in. It says that a policy change is an improvement if the beneficiaries of it could compensate the losers and still remain better off ��� even if compensation is not actually paid. This idea fills the Humean gap between the statements ���the benefits of reopening schools exceed the costs��� and ���schools should reopen���.

Which leads to the question I started with. I fear there are two problems with it, one philosophical, the other psychological.

The psychological problem is that it���s very easy to glide from ���the benefits exceed the costs��� to ���the benefits are high: the costs are low.��� Johnson might be guilty of this when he says the risk of getting Covid-19 in schools is "very small"; he forgets that a small chance of a nasty event is something to be avoided. On the Today programme this morning Tory MP Huw Merriman went further, declaring schools to be safe.

Brexit gives us another example of this. Many Leavers ��� especially those whose media profile is disproportionate to their cognitive skills - have gone from ���the benefits of Brexit outweigh the costs��� to downplaying any costs at all.

Rather than face tricky, marginal decisions we exaggerate benefits and understate costs. Psychologists call this the choice-supportive bias.

The philosophical problem arises from the fact that the winners and losers from reopening schools are different people. Children win by getting a better education, but school staff and their families lose because they face a higher risk of catching Covid-19. And even a small extra risk across tens of thousands of people adds up to a few certain deaths. How is it legitimate to impose death upon some so that others benefit, especially when they are not being compensated for that risk?

There���s a long tradition which says it is not. John Rawls objected that the Kaldor-Hicks principle (which is just a refinement of classical utilitarianism) ���does not take seriously the distinction between persons.��� And from a different perspective, Robert Nozick wrote:

There is no social entity with a good that undergoes some sacrifice for its own good. There are only individual people, different individual people, with their own individual lives. Using one of these people for the benefit of others, uses him and benefits the others. Nothing more. What happens is that something is done to him for the sake of others. Talk of an overall social good covers this up (intentionally?) To use a person in this way does not sufficiently respect and take account of the fact that he is a separate person, that his is the only life he has. He does not get some overbalancing good from his sacrifice, and no one is entitled to force this upon him. (Anarchy, State and Utopia, p32-33).

Reopening schools is, however, not the only example of the government ignoring Rawls and Nozick���s objections. The awarding of A levels did the same thing. Until the government over-rode it, Ofqual graded students not just on the basis of their own abilities but on the basis of their school���s past performance. As Frances says, ���the algorithm did not treat people as individuals. It reduced them to points on a curve.��� It too did not take seriously the distinction between persons.

In truth, policy often does this. And the costs it imposes are often not just pecuniary as they are with taxes or Brexit. Fiscal austerity and benefit sanctions killed thousands of people so that the media could get the sense that the public finances were under control. And wars in Iraq and Afghanistan killed tens of thousands in the hope of benign regime change.

Such decisions are not always the result of bad policy (not that bad policy is always avoidable). Whenever a local authority decides not to reduce a speed limit it is in effect imposing a higher risk of death or injury so we can benefit from greater convenience on the roads. As Tom says, ���at government level, everyone���s a utilitarian.���

Even in a liberal democracy, people are sometimes killed for the greater good. Rather than face this fact and think about it seriously, governments simply forget Rawls and Nozick���s objections.

Which brings us to a problem. Whilst we accept this in some contexts, we rail against it in others. Here���s James Bloodworth on the ���useful idiots��� who defend repressive regimes:

What is contemptible is the relegation of other human beings to pawns in the supposed historical process. The latter results in people uttering glib phrases about ���omelettes not being possible without broken eggs��� when bouts of mass killing threaten to undermine a favoured cause.

For me, Arthur Koestler���s Darkness at Noon was as much an attack upon classical utilitarianism ��� the idea that some should suffer or die for the greater good ��� as it was upon Soviet communism.

There is, then, an inconsistency here. Sometimes we accept deaths for the greater good and sometimes we don���t*, preferring to pretend that we cannot put a price on human life even though we often must.

This is not to accuse anybody of hypocrisy. Very few of us apply moral principles consistently (and perhaps we shouldn't). The brute fact is, though, that politics is sometimes a matter of life and death. This fact is like the first Mrs Rochester: we���d like to lock it away and forget it, but we cannot.

* I���m not sure this can be resolved merely by the fact that critics of the Soviet Union were in fact objecting to the ideal of communism rather than its implementation.

August 21, 2020

For (and against) a sovereign wealth fund

In their excellent Angrynomics Mark Blyth and Eric Lonergan recommend that the government borrows at negative yields to establish a sovereign wealth fund. There���s more to be said for this than they think, because the UK is better situated than many countries to have such a fund.

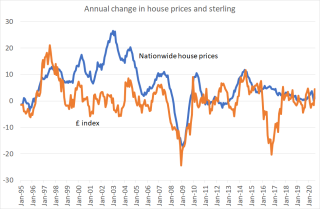

My chart shows why. It shows that sterling tends to fall when house prices do. In the mid-90s, 2008, 2011 and last year weakness in the housing market was accompanied by a weak pound.

Now, I���m using house prices here as a proxy for something more general ��� bad times for the UK economy generally. The chart therefore tells us that a UK-based investor makes a profit on foreign currency assets when the UK economy faces hard times. Although house prices didn���t fall then, the Brexit referendum in 2016 is another datapoint in support of this hypothesis: the markdown in UK growth expectations was accompanied by a markdown in sterling.

This isn���t merely because demand for sterling depends upon actual and expected economic activity. It���s also because sterling is regarded by global investors as a riskier currency than dollars, euros or Swiss francs - which means that in hard times, when risk aversion increases, they dump sterling. This is why sterling fell during the worst of the stock market falls this year.

This means that for the UK a SWF could be a countercyclical asset. In recessions a falling pound would mitigate losses on overseas equities and generate profits on gold, overseas bonds and foreign currency.

This year���s experience demonstrates this. In the day job I showed that a simple portfolio of dollars, gold, global equities cash and gilts would have lost barely anything during the worst of this year���s stock market falls even with half its money in equities ��� thanks to profits on gold and dollars. Slightly more cautious portfolios would have risen.

Because a UK SWF would hold up in bad times it can be a counter-cyclical device. Payments from the fund could be raised (slightly) in hard times without greatly jeopardizing its long-run returns.

Better still, it needs no skill to achieve this. The weights in my portfolio were based on no more than reasonable round numbers. That vindicates a point made by the LBS���s Victor DeMiguel, that na��ve diversification works well (pdf) (which itself is a specific instance of Robyn Dawes point (pdf) that there is a ���robust beauty��� in improper linear models.) We don���t therefore need a genius to run the fund. All we need is a mediocrity with a plausible manner to lend it authority. And the UK has an abundant supply of mediocrities with plausible manners.

Sadly, though, I fear this oversells a SWF.

One problem is that it will come under political pressure to invest domestically and to bail out struggling UK firms rather than to diversify internationally. I���m not sure Eric and Mark are selling an SWF when they suggest it bails out UK airlines. For the SWF, that should be a pure investment decision not a political one. If you think UK firms are starved of finance ��� and I���m not at all sure airlines would be exhibit A for this hypothesis - the solution is a national investment bank, not a SWF.

A second problem is that a SWF that was sufficiently cautiously managed to hold up in bad times would under-perform or lose money in good. Logically, this is no problem at all. One of the basic principles of financial economics is that what matters is your portfolio as a whole. If the SWF loses money when our other assets are doing well ��� our human capital and domestic businesses ��� there is therefore no problem. Quite the opposite: the SWF is doing exactly what it should.

Sadly, however, economic logic and the media are not often even nodding acquaintances. We can see this from today���s reports of UK government borrowing, which reveal an utter ignorance of the basic facts that balance sheets have two sides and that one person���s debt is another���s asset. The moment the SWF loses money ��� which of course even the best funds do sometimes ��� the idiotmedia will run stories of the ���scandal��� of ���taxpayers������ money being wasted.

From a portfolio management point of view, running a SWF is easy. From a political point of view, it is not.

August 20, 2020

Cents and sensibility

Would Labour have handled the A level fiasco better than the Tories? There���s a reason to think so, and it has nothing to do with the parties��� relative competence.

Instead, it���s because Labour ministers would have had different sensibilities, or sympathies. They would have been more awake than the Tories to the situation of 18-year-olds from poor schools and hence more alert to developments which might hurt them.

The point here is a Smithian one. Smith thought that sympathy ���arise[s] from an imaginary change of situations with the person principally concerned.��� But, as Smith saw, our imagination is limited. It���s easier to put yourself in someone���s shoes if you have actually been in them, or if you have friends or family in those shoes, or if you expect to be in them later. Although there are many exceptions on either side, Labour MPs therefore sympathize more with people from poor backgrounds whilst Tories are more likely to sympathize with landlords, bankers or bosses. For this reason, some sections of capital would have disproportionate influence over a Tory government even if not a single pound changed hands.

Not that capital wants to leave it at that. It���s the principle of sympathy that justifies JP Morgan hiring Sajid Javid. Politicians around the world will look at that and think ���that could be me���. This feat of imagination will increase their sympathies with bankers.

Obvious as it seems, this Smithian idea explains a lot. It explains why some people sympathize more with migrants than others. If you feel an outsider in the UK ��� say because of your race, class, sexuality or just idiosyncratic temperament ��� you���ll find it easier to put yourselves in the shoes of those who feel compelled to leave their country. Logically, rightist lovers of freedom should support freedom of movement as much as leftists. But differences in sympathies mean that in fact things are otherwise.

It also explains why so many on the left had misgivings about New Labour, even though it did much to help working people such as introducing the minimum wage and tax credits. There was a feeling that its sympathies lay more with bosses and bankers than with working people.

It also explains the long-running electoral success of the Tories. Their sympathies make them instinctively more likely to placate enough of the rich and powerful to earn a reputation for competence. Nobody gives a damn if your policies hurt single parents in Wigan.

Which is why it matters that top jobs are dominated by people from private schools. Because we all find it easier to sympathize with people like us, the dominance of the privately educated therefore skews decision-making (not least in the media) towards the interests of the rich and against those of the poor. And this would be the case even if the decision-makers were honest and of good will.

All this both justifies representative democracy and helps explain why it goes wrong.

Voters aren���t qualified to judge the technical competence of the parties, nor even their detailed policies ��� not even in aggregate, given that the conditions required for the wisdom of crowds are absent. What they can do, though, is say which set of sympathies they prefer. And that's reasonable. In politics there is an agency problem - the danger that the government won't act in our interests. Knowing that its sympathies are in line with our own, however, reduces this risk.

Differences in sympathies, however, can also help explain some of the bigger policy failures of our times. Thatcher���s introduction of the poll tax arose from not sympathizing with people who didn���t own property. The occupations of Iraq and Afghanistan might have been less disastrous if New Labour had better sympathy with military men, and wouldn't have occurred at all if Blair had more sympathy for working people and less for George Bush. The introduction of Universal Credit would have gone better had there been sympathy for benefit recipients. And so on up to the A level mess.

Which brings us to a problem. The greater are divisions within a society, the harder it is for one side to sympathize with the other. Which means that policy errors are more likely. As long ago as 1995 Patrick Dunleavy argued (pdf) that the UK was ���unusually prone to make large-scale, avoidable policy mistakes��� ��� a point confirmed by Ivor Crewe and Anthony King in The Blunders of our Governments and of course corroborated by subsequent events. Which poses the question. Might it be that this unusual proneness to error arises in part from our deep class divisions*? If so, then good technocratic government actually requires the abolition of those divisions.

* Dunleavy, Crewe and King offer more proximate explanations for bad government. But at least one of these - overconfidence - is most certainly a class issue.

August 18, 2020

Algorithms & reification

The A levels U-turn has prompted the question: what went wrong with the algorithm?

The answer is: nothing, zip, diddly, jack.

What went wrong wasn���t the equation, but people. People create algorithms and they do so according to the principle garbage in, garbage out. The error here was not of high-level maths. It was a basic failure to appreciate the nature of statistics. Statistics cannot discover what isn���t there. And the information we really needed ��� how to compare students across schools ��� just wasn���t there. As the great Dan Davies puts it:

No statistical method in the world is going to be able to give you good results if the information you���re looking for is fundamentally not there in the dataset that you���re trying to extract it from

The problem wasn���t the algo. It was that the people in charge of it combined stupidity with class hatred. And it is of course not good enough for Williamson to claim that ���Ofqual didn't deliver the system that we had been reassured and believed that would be in place.��� Ofqual isn���t some organic food company delivering a strange-looking vegetable. It is, or should be, under government control.

What���s going on here is in fact an old and widespread error. Its what Georg Lukacs called reification ��� the process whereby ���a relation between people takes on the character of a thing���. What actually happened was that people in power allocated A level results. That���s a relation between people. But to some, this relation appears as a thing, an algorithm. Which effaces the basic fact that those in power are the enemy of young working class people.

With algorithms and big data becoming increasingly important, the danger is that the reification fallacy will increasingly serve as a means of effacing the reality of class power.

In fact, of course, it has done so for decades. When Luddites smashed machines, they were transferring their anger from people to things ��� just as people do today when they rail against IT systems failures rather than against the mismanagement that create them.

And in 1845, Marx described how capitalism appears to people not as the product of human action but rather as ���an alien power existing outside them, of the origin and goal of which they are ignorant, which they are no longer able to control.��� Of course, this does not mean that specific individuals are always to blame as they are in the A level case: often, social outcomes are emergent, the product of human action but not human design. Nevertheless, they are human-made.

A classic example of this reification is how some people use the phrase ���market forces��� to defend income inequality. What this misses is that ���the market��� is not some entity existing above us but is really only a relation between people. And it is a relation of power. As Rick said, ���all pay is, ultimately, a function of power.��� Bosses and bankers have power; they must be bribed not to misappropriate their firms��� assets. But care-workers do not ��� often because they are women and migrants who lack outside options.

All this, of course matters for the reason Marx thought it did. If we regard inequalities and inefficiencies as arising from abstractions ��� be they algos or market forces ��� we are apt to either attack the wrong target or, worse still, to resign ourselves to fate. We need not do either. Technology - which includes social technologies such as markets - is a human construct.

August 16, 2020

Empirical vs fantasy politics

News items this week have highlighted an under-appreciated political division ��� between issues that involve clear harm to identifiable individuals and those that don���t.

Contrast the crime* that is the mishandling of A levels with reports of migrants crossing the channel in dinghies. There���s a massive difference between the two. The mis-marking of A levels imposes real suffering upon identifiable people. But a few migrants in dinghies do not: even if you believe ��� wrongly ��� that immigration cuts wages and jobs, it is not the few desperate people who arrive in boats that are doing so.

The latter ��� what Chris Grey calls an ���artificial emergency��� - is not the only example of reified, unempirical politics that is unconcerned with real material harm. The BBC reports on record government borrowing without pointing to a single individual who is suffering because of it. Claims that borrowing imposes a burden on future generations miss the point that government borrowing is also an asset for some people, and that such borrowing bequeaths assets to future generations in the form of better infrastructure and education, and by preventing the loss of businesses and skills that would occur if borrowing were not so high.

Similarly, even the more articulate Brexiters often fail to point to a material harm done by being in the EU or a material benefit from leaving, preferring to speak of windy abstractions such as sovereignty. Of course, the EU like all human institutions has its faults, but leaving on account of its fisheries policy is like jumping out of a plane because you don���t like the in-flight meal. And if you really want to boost UK exports, there are countless better ways to do so than trying to negotiate new trade deals.

These are serious examples of unempirical politics, but there are unserious ones too. At a time when thousands of people are losing their livelihoods, futures and even lives because of government incompetence, the Times saw fit yesterday to run a piece fantasising about a Labour government nationalizing Marx and Spencer (ooh, my sides are splitting).

Compare all this to empirical people-based politics. Issues such as poverty, the inadequate benefits system, excess deaths from Covid-19, mass job losses and a decade of wage stagnation all involve real material suffering.

This division between the politics of empirical suffering and the politics of fantasy and abstraction overlaps to a large extent with the left-right divide. In recent years much of the left has focused upon the empirical harms of poverty and austerity whilst the right has been obsessed with sovereignty and ���control of our borders.���

From one perspective, this is an odd inversion. Those of us formed in the 70s were told that conservatism was an empirical tendency concerned with the amelioration of identifiable evils whilst the left had abstract utopian visions. Here, for example, is Oakeshott (pdf):

[The conservative] thinks that an innovation which is a response to some specific defect, one designed to redress some specific disequilibrium, is more desirable than one which springs from a notion of a generally improved condition of human circumstances, and is far more desirable than one generated by a vision of perfection.

By this standard, it is the left that is conservative, worried about specific defects of poverty and the mismanagement of the exam system whilst it is the right that has a ���vision of perfection���, a vision of perfect sovereignty and controllable borders.

In this divide, the BBC ��� let alone the rest of the media - horribly fails to maintain due impartiality. Imagine the mass media didn���t exist so your only knowledge of political issues came from the personal experience of you and your family, friends and neighbours. How would politics appear to you?

Chances are, empirical issues would loom large. You would know people who hadn���t had a real pay rise for years; had missed a top university place; or was worried about their job or business. Most of you wouldn���t, though, feel any material harm from being in the EU and would not know a few dozen migrants were crossing the channel. In drawing our attention to the latter and diverting us from the former, the media biases us against empirical politics. ���Due impartiality��� is not merely a matter of how the BBC reports particular issues. It is about what it chooses to report.

But why has this left-right division between empirical and unempirical politics emerged? It���s a relatively recent development. Thatcher, for example, attempted to solve genuine problems such as inflation and our poor economic performance.

Personally, I doubt that it���s because rightists suffered a bang on the head all at the same time. Instead, I suspect it is because extractive rentier capitalism precludes ��� to a greater extent than used to be the case ��� remedies for specific defects. Which means that fantasy politics is all the right have got.

* I say ���crime��� because three unforgiveable errors are involved: the class war that has seen students from poor backgrounds hit hard; the fundamental misunderstanding of statistics (no method can uncover information that���s just not there); and the failure to appreciate that there was an obvious solution.

August 15, 2020

Limits of radicalism

Earlier this year, Dominic Cummings appealed for "more genuine cognitive diversity" in government, wanting to hire "true wild cards" and weirdos. The A level results which have seen talented students punished for being poor shows that he has not yet achieved that ambition.

I say this because there was in principle an obvious solution. The government should have adopted a version of the Texas 10 per cent rule, which requires that the top 10 per cent of students from each school be admitted to Texan state universities. Adapting this to the English case would have meant asking schools to give A* grades to the best 8.9% of students in each subject, A grades to the next 18.7% and so on (I've used these numbers to match this year's distribution of grades.)

Such a system would have had six great advantages. It would have avoided the problem of trying to compare students across schools in the absence of public exams. It would have been more transparent than this year's effort at standardization. It would have prevented grade inflation, as the proportion of grades could have been determined in advance. It has a proven track record: it has worked well enough in Texas for years. It would have ensured that grades were determined by those who most knew what they were doing. As Ofqual itself says (pdf):

The best judges of the relative ability of students in a school or college were the teachers who had been preparing these students... we know from research evidence that people are better at making relative judgements than absolute judgements and that teachers��� judgements tend to be more accurate when they are ranking students rather than estimating their future attainment.

And it would have embodied a principle of equality of opportunity, as it would reward students for their own efforts and abilities and not have punished them for going to poor-performing schools. Although John Roemer best articulated this principle, it is also a Thatcherite one: she wanted "a land in which individuals will have a fair chance, by their own efforts, of winning happiness". The Texas rule fulfils this aim better than an algorithm which punishes people for their background.

Sure, there would have been a few issues: how to treat borderline cases, or schools where very few students sat some subjects. But these issues are surely minor compared to those afflicting the current system.

Which poses the question: why was this method not even discussed (at least in public)?

Ignorance is no excuse: I was writing about the Texas rule 16 years ago, and anybody who knows less than me is utterly unqualified for any position of authority.

Instead, it's because it challenges the class system in two ways. For one thing, it would require the government to respect the judgement of teachers and to treat them as professionals rather than proletarian objects of managerialism. And more importantly, such a rule would advantage bright people from poor schools and penalize mediocre ones from posh schools - which would undermine the point of the UK class system*.

What all this shows is that Cummings' radicalism is if not fake then at least limited. Cognitive diversity and weirdness must stop at the point when it challenges class privilege.

Of course, Cummings is not alone here. There's a long tradition of posh people pretending to be radical, up to the point at which their own privilege is challenged. George Orwell (not perhaps a wholly reliable witness) wrote in 1937:

The typical Socialist is not, as tremulous old ladies imagine, a ferocious-looking working man with greasy overalls and a raucous voice. He is either a youthful snob-Bolshevik who in five years' time will quite probably have made a wealthy marriage and been converted to Roman Catholicism; or, still more typically, a prim little man with a white-collar job, usually a secret teetotaller and often with vegetarian leanings, with a history of Nonconformity behind him, and, above all, with a social position which he has no intention of forfeiting...most middle-class Socialists, while theoretically pining for a class-less society, cling like glue to their miserable fragments of social prestige.

Mutatis mutandis, we see similar things nowadays. Greg Dyke called the BBC "hideously white" without actually solving the problem. "Satirists" mocked the government but shat their pants when presented with a mildly social democratic alternative. Class tourists think that poor is cool. We see it too in woke capitalists; in Guardian types who think that "cool and edgy" are terms of praise rather than indicators of unutterable kack; in some leftists who favour crank conspiracy theories over proper class analysis; and in celebs who profess to be green whilst using private jets. And this is not to mention the slightly different but equally long tradition of "angry young men" of the 50s, "hip young gunslingers" of the 70s or RCPers of the 80s becoming tiresome reactionaries.

Cummings' radical posture is therefore part of a long and widespread tendency. What's going on here?

The question gains force from an intellectual tradition - associated with Burke and Oakeshott - which has linked political conservatism (preserving inequality) with cognitive conservatism (scepticism about the power of rationality). If you're benefiting from the system, why rock the boat? The cognitive biases programme should, in principle, have reinforced this link by teaching us of the tight limits of our abilities.

So, why do we so often see those with a vested interest in preserving class hierarchies profess a form of radicalism? There are countless possible explanations, among them daddy issues and the tendency for posh schooling to inculcate the over-confident belief that one knows better than the wisdom of ages.

But there is a kinder explanation. Actually-existing British capitalism is unjust and inefficient. The smarter and better beneficiaries of the system recognise this. Yes, doing so whilst retaining class privilege makes them hypocrites, but hypocrisy is the tribute that vice pays to virtue.

* It would, of course, be unfair to characterize this government as comprising posh mediocrities. Many of them cannot even aspire to the dizzy heights of mediocrity.

August 13, 2020

On woke capitalism

Just because you are an idiot doesn't mean you are always wrong. So it is with James Cleverly's denunciation of Ben & Jerry's "virtue-signalling" after the company spoke out against the government's ill-treatment of migrants.

The thing is, he was right. Ben & Jerry's fine words contrast with the company's reluctance to improve the rights of its own workers until it came under huge pressure to do so - thereby demonstrating the truth of Marx's claim that "capital is reckless of the health or length of life of the labourer, unless under compulsion from society."

But of course, Ben & Jerry's are not alone in their hypocrisy. Amazon (among many other companies) has spoken in support of Black Live Matter despite being a notoriously bad employer. Facebook and Twitter bosses have supported BLM whilst allowing race hate speech on their sites. Starbucks enthusiasm for being "an ally to the lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgender and queer community" is matched by its enthusiasm for avoiding tax. And as Sarah O'Connor points out, several "sustainable" fund managers are better at PR than at actually forcing improvements in working conditions. And so on and so on.

Blackwashing is the new greenwashing. Luke Savage is right. What we're seeing here is "the commodification of social justice" - using virtue-signalling to shift more product. Sometimes, the twin goals of capitalism - raising profits and trying to legitimate the system - happen to coincide.

All of which poses the question: is "woke capitalism" feasible or even desirable?

Certainly, capitalism has historically been associated with patriarchy, racism and slavery - although the contribution of the latter to capitalism is still a matter of debate. But of course, so too have been other modes of production.

The question is: are racism and sexism inherent features of capitalism?

There are two reasons to suspect so. One is that racism fulfils a useful function by dividing the working class and promoting national identity at the expense of class consciousness: Tory and media attempts to stir up anti-migrant feeling whilst employment is collapsing is just the latest example of this.

The other is that in capitalism those with little bargaining power lose out relative to others - which means that women and migrant workers often get a raw deal. In this context, the idea that sexism and racism could be eliminated if only capitalists were more woke is a mistake. Some injustices arise from emergent processes independent of intentions. As Marx wrote:

[The fate of the worker] does not, indeed, depend on the good or ill will of the individual capitalist. Free competition brings out the inherent laws of capitalist production, in the shape of external coercive laws having power over every individual capitalist.

Granted, some have been more optimistic about these external coercive laws. Gary Becker, for example, thought that competition could eliminate discrimination - although it seems it is yet to actually do so.

Let's assume, however, that all this is wrong and that capitalism could be woke, in the sense that there were no gender or ethnic pay gaps, that women and minorities were as likely to achieve prominent positions as white men, and that there was no racism or sexism in the workplace. What then?

Well, every criticism Marx made of capitalism would still be on the table. Marx did not criticise capitalism because of its racism and sexism* - a fact that has historically led some Marxists to understate the importance of these. Instead, his complaints were that it was alienating, oppressive, a force for inequalities in wealth and power, and prone to crises and stagnation. The fact that capitalism currently works to the disproportionate benefit of mediocre white men is but one of its flaws.

Of course, you can deny the force of these criticisms. But the point is that Marx's critique of capitalism is independent of racism and sexism. Even if we had the most perfectly woke capitalism, Marxists would find huge problems with the system. (I think rightly, but that's by the by.)

All of which is to endorse Helen Lewis's point, that there's a big difference between social and economic radicalism. Some - maybe many - capitalists might be the former, perhaps sincerely. But they are not the latter.

* With the caveat that the process of primitive accumulation was often accompanied by racism.

August 11, 2020

A policy failure

Sometimes, the humane thing to do is also economically efficient, and this government is doing neither. This is the message of today���s employment numbers.

We must not be fooled by the fact that unemployment, at 1.34 million, fell slightly in the second quarter and is unchanged from a year ago. This disguises huge job losses. PAYE data show that the number of employees fell by 740,000 between February and July. And as the furlough scheme is withdrawn, further job losses are likely. On top of this, the numbers of self-employed slumped by 238,000 in Q2,

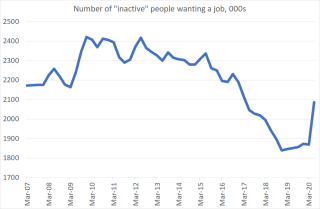

So, why didn���t unemployment rise? One reason is that there have been lots of jobs lost among the over-65s: 161,000 in Q2. Many of these will have returned to retirement. The number of people who are economically inactive but would like a job rose by 218,000 in the quarter.

A second reason is that it is foreigners who have lost jobs: the number of non-UK people in work fell by 327,000 in Q2. Some of these will have gone home.

All of which poses a danger ��� that the economy has lost potential supply. Some of those migrant workers (and perhaps some of the over-65s) might not return to the UK if or when labour demand picks up. The formerly self-employed might decide that self-employment is too precarious for them and so seek staff jobs instead. That will cause shortages for those industries (such as much of the entertainment business) dependent upon the flexibility that freelancers offer. And to the extent that small businesses close, their surviving rivals will enjoy greater monopoly and pricing power.

If we get a decent recovery in demand, therefore, it might stoke up inflation. Not very much inflation, granted. But enough to limit the expansion somewhat. What should have been a temporary shock might therefore have longer-lasting adverse effects upon potential growth.

This is a policy failure. In theory, the government could have preserved the economy in aspic when we went into lockdown thus protecting all jobs and businesses, taking it out only when the threat of Covid-19 passed. It did not do so. Instead, as James Smith at the Resolution Foundation says, the support was inadequate and ��� as Paul Evans notes ��� insufficiently targeted at freelancers.

Which poses the question. Why has policy failed?

I don���t think the main reason was concern about horizontal equity ��� paying people to do nothing is unfair on those still working.

I suspect a stronger reason was insufficient intellectual flexibility. The Tories aversion to massive intervention in markets is reasonable in normal times but inappropriate in a crisis when the pandemic prevents normal market functioning*. They failed to make a big enough shift.

Also, there has been a lack of policy infrastructure. What we most needed back in March was immediate and massive support for everybody. But as Eric has pointed out, the systems were not in place for this. And whilst there were possible ways of working around this ��� as Eric has shown - both the Bank and the Treasury weren���t sufficiently intellectually agile to adopt such methods. One lesson of this crisis is that the government should put the infrastructure in place to ameliorate the next downturn ��� so that a basic income, job guarantee or helicopter money can be swiftly introduced.

Perhaps the greatest reason for the failure, however, is that the government (and media) make a fetish of the public finances. Even Faisal Islam ��� who should know better ��� has said that the furlough scheme is ���being paid by the taxpayer.��� You don���t need to believe MMT to see this is not quite right. The cost of supporting jobs need not and should not be borne by current taxpayers. The government can borrow over decades and so spread the cost not only to our grandchildren but to their grandchildren too: It���s only a few years ago that the government paid off the fiscal cost of the Napoleonic war. Better still, this cost falls over time. 25-year gilts now yield minus three per cent in real terms, which means that for every ��100 the government borrows today it need repay less than ��50 in today���s money over the next quarter-century.

If I���m even ball-park right that today���s losses of jobs and businesses will reduce future capacity, and that they are due in part to the fiscal fetish, we have a nice irony ��� that an attachment to ���sound money��� might prove to be inflationary. In policy-making, intentions and outcomes are sometimes different things.

* I say pandemic rather than lockdown because, as Sweden���s fall in GDP shows, Covid-19 would have reduced economic activity even without a lockdown simply by scaring people out of shops and offices.

August 6, 2020

Government for spiv and rentier

���The executive of the modern state is but a committee for managing the common affairs of the whole bourgeoisie.���

Recent news seems to vindicate Marx���s aphorism. Today, Robert Jenrick relaxed planning laws a few months after seeing big donations to the Tories from property companies. This is of a pattern with his giving planning permission for a development by Richard Desmond soon after Mr Desmond made a donation to the Tory party. Support for jobs and businesses is being used to pay dividends and big CEO salaries. And an advisor to Liz Truss made millions from selling unusable PPE to the NHS.

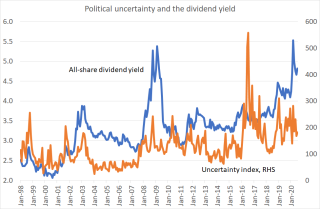

Not so fast. My chart tells another story. It shows that there is a decent correlation (0.48 since data began in 1998) between the dividend yield on the All-share index and UK political uncertainty, as measured by Baker. Bloom and Davis*. Greater political uncertainty means lower share prices. The Brexit referendum, and uncertainty about the terms of our exit last year, greatly depressed share prices. In creating political uncertainty ��� much more so than under most of the Labour government ��� the Tories have costs capitalists billions. And with uncertainty still well above its long-run average, this cost is ongoing.

How can we reconcile this with Marx���s claim?

One possibility is that it shows that the state has a degree of autonomy. It does not mechanistically always do the bidding of capital.

Another answer is that the government is not the same as the state. The government comprises damn fools who do all sorts of silly things. But essential functions of the state do serve capital���s interests ��� for example, in providing infrastructure, skilled (and quiescent!) workers, protection of property rights and economic stabilizers to mitigate recessions.

But there���s something else. Although capital has some common interests, it also has conflicting ones: bankers versus manufacturers; small businesses versus monopolies; landlords versus retailers. And so on. The interests this government is best serving are not those of productive capital. Whilst it is cutting red tape for property developers it is imposing billions of pounds of it onto road hauliers and exporters. And whilst the lockdown is jeopardizing countless smaller businesses, the government is protecting banks and landlords.

It is, then, promoting the interests of rentiers (pdf) and spivs.

Which poses questions. Does this tell us about the character of this government, that it should align itself with shysters? Or does it instead tell us something about the nature of British capital ��� that its most regressive elements are those that are now most dominant?

* The correlation is far stronger between the yield and global policy uncertainty, where the latter has been raised significantly by the Orange Cretin.

Chris Dillow's Blog

- Chris Dillow's profile

- 2 followers