Chris Dillow's Blog, page 15

February 13, 2021

Choosing charlatans

People choose to listen to charlatans even when it is against their interest to do so. That���s the message of some recent experiments.

Aristotelis Boukouras and colleagues got subjects to take a multiple choice exam during which they could choose to take help from one of two computerized advisors. One of these was an expert, who gave the answers that a panel of economists would. The other gave the answers that had been most popular with other people who had taken the test. They found that most people chose to take advice from the latter ��� even after they had been told that it was only giving the popular answers and even when they were paid for getting answers right. What���s more, even when people had the option of switching to the expert when they could see that the populist advisor was wrong, only around half did so. They concluded:

A charlatan espousing popular beliefs can lead laypeople to choose to follow her advice rather than the advice of a genuine expert. This is true even in the face of increasing negative evidence regarding the accuracy of the charlatan.

What���s going on here is a variation on the confirmation bias. ���People have a strong tendency to follow the adviser who suggests similar answers to the people���s own priors��� the authors say. And it is the charlatan, who gives the most popular answer, who is the more likely to do this.

This has been corroborated by some different recent experiments by Basit Zafar and colleagues. They asked people which articles about the pandemic they wanted to read, having shown them just the headlines. They found that pessimists tended to choose articles with pessimistic headlines and optimists articles with optimistic ones. What���s more, having chosen articles in line with their priors they then revised their beliefs more if the article confirmed their priors ��� so pessimists who chose to read a pessimistic article became even more pessimistic about the outlook for deaths and jobs whilst optimists who chose optimistic stories became more optimistic. In this way, beliefs became more polarized; this finding of course confirms earlier evidence (pdf).

Of course, these experiments have external validity. People believe Covid denialists and those who claimed economic benefits from Brexit. And they even believe charlatans when their own money is at stake ��� for example by investing in high-charging under-performing funds.

The thing about these experiments, though, is that people choose the charlatan even under ideal conditions. In the real world there are many other ways for charlatans to build support as well even ignoring the biased and ignorant media. These include:

- Ideological homophily. Boukouras and colleagues asked questions that weren���t hot ideological issues. Many issues on which we seek expertise, however, are. This causes right-wingers to regard Econ101ers as experts and MMTers as cranks whereas leftists do the opposite.

- Herding effects. As Robert Shiller shows in Narrative Economics, stories can spread exactly like viruses. This is one reason why asset price bubbles occur and why friends and colleagues have shareholdings and asset allocations (pdf) that are more similar than they should be.

- Ignorance of selection bias. David Hirshleifer gives an example of this. People talk more about their investment successes than their failures. This causes listeners to over-estimate the probable success of active stock-picking relative to sticking money in tracker funds, and to over-invest in speculative stocks.

- Lack of incentives. Even when people have big money at stake, they sometimes make bad decisions, for example by buying high-charging, low-performance actively managed funds. How much more likely are they then to make mistakes when incentives to be right are absent? As Jason Brennan has said, ������when it comes to politics, smart doesn���t pay, and dumb doesn���t hurt.���

- Snake oil sales tricks. In a brilliant paper (pdf), the late Werner Troesken showed how sellers of patent medicines stayed in business for decades by tricks such as: giving people a short-term pick-up with alcohol or opium that they mistook (pdf) for a genuine cure; appealing to people���s desperation (they knew, decades before prospect theory, that desperate people take risks); hyping their products and distinguishing them from others; and denigrating experts.

One implication of all this is that a public service broadcaster as the BBC purports to be cannot be impartial. If you offer people two sides of a story or two talking heads, many will choose the charlatan or false story over the true one. And we���ll get increased polarization ��� which might make for good TV but not necessarily for good politics or a good society.

But I think the implication is more devastating. All this undermines the conventional liberal faith in the marketplace of ideas. John Stuart Mill thought that ���wrong opinions and practices gradually yield to fact and argument.��� Experiments, however, confirm our real world experience that in fact the opposite can happen. And this isn���t simply because of our biased and dysfunctional media.

But let���s push the ���marketplace of ideas��� metaphor a step further. Markets must be embedded within social norms, rules and mechanisms if they are to work effectively, as Jesse Norman argues. In the marketplace of ideas these norms, rules and mechanisms are obviously inadequate. Which poses the question: what would effective ones look like? Too few people are asking this question ��� which might be because existing ones actually serve the interests of extractive capitalism rather well.

February 6, 2021

Labour's patriotism problem

Patriotism might be the last refuge of the scoundrel but it is the first refuge for a politician wanting to avoid the reality of the need for radical change. That seem to be the message of the call by some ���branding agency��� that Labour should appear more patriotic.

Which poses a question. How is it that Labour���s patriotism has come into doubt? For reasonable definitions, it is Labour that is the patriotic party more than the Tories.

Let���s define patriotism as love of one���s country, and let���s define love as wanting what is best for someone whilst valuing them as themselves, and the country as its inhabitants, past present and future.

By these definitions, Labour is patriotic. It wants what���s best for people. Of course voters rejected Labour���s conception of what���s best for them, but children sometimes reject their mother���s ideas of what���s in their interest (sometimes rightly!) - but this doesn���t mean their mother doesn���t love them.

By contrast, Tory policies have at least sometimes been motivated not by a genuine desire for the public good but by personal ambition. Cameron���s disastrous decision to hold a divisive EU plebiscite was motivated by a desire to strengthen his power over eurofanatics in the party: Johnson���s becoming a Brexiter owed more to his own ambition than to the merits of the case; and perhaps Sunak���s pushing for an early end to the lockdown is based on a desire to win favour with Tory MPs opposed to the restrictions.

And Labour ���more than the Tories ��� loves Britain for what it is. Orwell famously described England as ���a family with the wrong members in control���. Which is how social democrats have seen it. As Phil says, Labour���s ambition has been to redefine the image of the nation as one ���in which everyone has its place - a one nationism from below���. Hence Rebecca Long-Bailey���s talk of progressive patriotism and Lavery, Smith and Trickett���s claim that ���it is possible to love your country and learn and reflect on its history proactively and critically.���

Again, this contrasts with the Tories, who have often expressed hatred for much of the country. Johnson has claimed that Muslim women ���look like letter boxes���; that Liverpool wallows in victim status���; and that the children of single mothers (including me) are ���ill-raised, ignorant, aggressive and illegitimate���. And this is not to mention the Tories��� long history of racism, homophobia and class hatred, reinforced in recent years by contempt for the young.

This disdain for many of our people is matched by attacks upon our institutions such as the BBC, judiciary, universities and local government ��� attacks which signify a distaste for the traditional British ways of doing things.

And of course, several of the Tories��� cheerleaders don���t love Britain enough to pay taxes or even live here.

The Tories��� relationship to the country is like that of an abusive husband towards his wife. He might claim that he loves her, when in fact he belittles her and seeks only to control her.

From this perspective, therefore, it is Labour that is the patriotic party, not the Tories.

Why, then, does it seem otherwise? It���s because my definition of ���the country��� is dubious. As Ed West says, there are two patriotisms. In the second form, the ���country��� is not so much its inhabitants but a collection of symbols: the flag, the armed forces, the monarchy and ��� yes ��� a largely false image of history. It is these that ���patriots��� love. To paraphrase Tom Paine, they love the plumage but care little for the bird. Yes, all nations are imagined communities, but the Tories vision of the nation is a reified one. And when some on the left question this, they allow themselves to be painted as unpatriotic.

And insofar as Tory ���patriots��� think of the ���country��� as being a group of people, they do not identify it with all the people. Their image of Britain is less than fully-focused upon the burka-clad Muslim or gay man. Such a restricted view of the political community is of course an ancient one. Here is C.B.Macpherson on 17th century attitudes to the poor:

The Puritan doctrine of the poor, treating poverty as a mark of moral shortcoming, added moral obloquy to the political disregard in which the poor had always been held...Objects of solicitude or pity or scorn and sometimes of fear, the poor were not full members of a moral community...But while the poor were, in this view, less than full members, they were certainly subject to the jurisdictions of the political community. They were in but not of civil society. (The Political Theory of Possessive Individualism, p226-27)

Such a view leads to absurdities such as claims that ���the country can���t afford��� to support the poor and that ���keeping the country safe��� consists in a strong military rather than a decent welfare state. The Tories��� view the state as an iron fist not a helping hand.

Which brings us to Labour���s problem. This conception of patriotism is so well-entrenched that it is unlikely to be defeated by weapons as puny as fact and logic. I therefore have little problem in itself with Sir Keir wrapping himself in the flag: politicians must campaign in lies but govern in truth. The problem is that as such plastic patriotism might be, as Tom Blackburn says, not so much a packaging for social reform as a substitute for it.

February 3, 2021

Hedge fund humbugs

At the end of the Wizard of Oz the wizard is revealed not to be somebody of superhuman powers but ���just a common man���, ���a humbug���. Hedge fund managers are like that. Whereas their enemies, such as some of the posters on Wall Street Bets and indeed many on the left generally, sometimes pretend that they are evil geniuses the truth is much more mundane.

Data from Hedge Fund Research tell us this. They show that the average hedge fund has made 5.6% a year in the last five years. That might sound OK. But you could have made twice as much by just leaving your money in a fund that tracks MSCI���s world index; over 10 per cent in gold; and 3.8% in US Treasuries. Which means reasonably balanced funds which any investor could create for themselves have done as well as the hedge fund; in recent years any fool could have been a decent asset allocator.

The average equity market neutral fund ��� the sort that takes short positions in stocks - has done worse than this, making less than 2% in this time.

Of course, some funds have done much better ��� but then, somebody wins the lottery every week ��� but others have done worse. Crispin Odey���s Odyssey fund, one of the UK���s higher-profile funds, has lost almost 50% since 2016.

Hedge funds, though, aren���t the only mediocre funds. Conventional equity unit trusts also do badly. The Financial Conduct Authority says these ���did not outperform their own benchmarks after fees.��� And David Blake and colleagues have concluded that (pdf):

Almost all active fund managers fail to outperform the market once fees are extracted from returns.

Hedge fund managers, like their conventional counterparts, are not great wizards.

If you believe the efficient market hypothesis ��� which says that all information is in the price and that you therefore cannot beat the market except by taking extra risk ��� this is just what you���d expect.

But there���s a puzzle here. As I���ve said for ages in my day job, there are two (and perhaps only two) well-attested ways to beat the market ��� by investing in defensive (pdf) stocks or simply in ones that have risen in recent months. We���d expect many funds to do well simply by adopting these strategies.

And yet they don���t. Why not?

Many do try to exploit momentum: several of the most shorted stocks in the UK are long-term munters such as Cineworld, Premier Oil or Metrobank. But it���s dangerous to short even bad stocks because their prices can jump quickly: in the first two weeks of November, for example, Cineworld���s price jumped 50%. Such jumps require shorters to put up more cash ��� the margin call, which, says Dan Davies, is ���one of the most frightening things in the financial world.��� Shorting is much easier in theory than in practice ��� which is one reason why markets are not fully efficient.

This, however, just raises the question: if hedge fund managers are duffers, why are they rich?

It���s because they are clever not at asset management but at asset gathering. They make their money from fees: why do you think they go to the hassle of dealing with clients rather than simply trading at home on their own account? Hedge funds typically raise money from other institutional investors who are managing it on behalf of you and me. And as Milton Friedman pointed out years ago, when people spend other people���s money on other people, ���they don���t economize and they don���t seek the highest value���.

Many also benefit from a tax break: their fees are taxed at an anomalously low rate.

My point here is more about politics than finance. Our class enemy are not evil geniuses practising some arcane magic; investing successfully requires little intellect. Instead, they are beneficiaries of emergent processes such as principal-agent failures and deference towards the rich and of the cronyism that gives them special treatment from the state. There are no wizards, just common little humbugs.

January 31, 2021

On attitudes to risk

There���s a nice juxtaposition between two of the biggest stories of recent days: retail investors piling into Game Stop; and the reluctance of ethnic minorities to take Covid vaccines and the slowness of the European Medicines Agency to approve them.

The thing is that these are all stories about extreme attitudes to risk. Small investors buying a dodgy company looks like risk-loving behaviour, whilst refusing to approve or take the vaccine looks like high risk aversion.

What explains such a big contrast?

Conventional neoclassical economics has no answer. It sees them as mere differences in tastes, which it regards as exogenous.

This won���t do. It���s just shrugging your shoulders. Not that this is the only problem they have. As Thaler and Rabin have shown, the standard approach to attitudes to risk predicts that we reject even good bets. And in fact, it struggles to explain such a basic fact as why people both gamble and buy insurance.

There is, however, a much better way of thinking about people���s attitudes to risk, inspired by a paper (pdf) by Michael Woodford and colleagues.

When we think about a risk, such as a 50-50 chance of winning or losing ��100, it���s natural to ask: how would I feel if I lost or won ��100? We try to translate expected monetary values into mental states. But this translation, says Woodford, is prone to ���noisy coding��� and yields answers that are only ���approximate���. Faced with the same gambles, therefore, willingness to bet can vary from person to person not because of differences in the marginal utility of wealth, but because of differences in coding. And in fact, the same person���s willingness to bet will vary from context to context because the coding varies.

This might seem trivial, but it explains a lot. For example:

- Why we gamble and buy insurance. The questions ���how would I feel if my house burnt down?��� and ���how would I feel if I lost ��1000 in the casino?��� have answers which are coded very differently. It���s not that we have different marginal utilities over wealth as Friedman and Savage claimed (pdf). It���s that these are utterly different questions.

- Why we pay more to cut risk from (say) 10% to zero than from (say) 30% to 20%. It���s difficult to translate a 20% chance into mental states, so we still face uncertainty. A zero probability, however, eliminates this uncertainty. And we���re willing to pay for that.

- Why some people back longshots or speculative stocks despite their poor prospects. In terms of expected value, a 1% chance of a ��1000 win is worse than a 15% chance of a ��100 win. Some people, though, code it differently. They figure that ��1000 will do more than ten times as much good for them as ��100 ��� for example by allowing them to break even after past losses or to pay off their debts. (This is of course compatible with prospect theory).

- Why some are reluctant to take the vaccine. Mere talk of the issue raises the subject of death and so colours the coding: ���the jab could kill me���. This is especially true for people who distrust authority.

- Why our attitudes to risk aren���t always accurate as a guide to future utility. Just before the 2008 crash, Christoph Merkle asked UK equity investors how they���d feel if they lost a lot. He then surveyed them after they had actually lost money. And he found they were less miserable than they expected to be. This is consistent with noisy coding. In early 2008, it was difficult to translate a 20% loss into a mental state. By the end of the year this difficulty had disappeared. (I suspect people in early 2008 under-estimated the extent to which they���d be comforted by the knowledge that everybody else was in the same boat.)

- Why bubbles sometimes form. One driver of them is a shift in coding. Investors change from ���this stock could lose me money��� to ���if I don���t buy I���ll miss out.��� And ��� in Game Stop���s case ��� to ���my buying will sock it to hedge funds.��� In this way, investors anaesthetize themselves against the possibility of loss.

- Why people more capable of cognitive reflection (pdf) tend to take more risks. It���s because they are better at coding expected monetary values into mental states, and so face less uncertainty.

What we have here, though, is not merely a story about attitudes to risk. It���s also a story about how some of the presumptions of neoclassical economics are doubtful. It presumes that our preferences can be described by a simple equation describing marginal utility. But this needn���t be so. Our psychology is more interesting than that. It also presumes that preferences are just given. But in fact we can intelligently ask how they are formed. For example, past losses can make us more risk-seeking to get even, and good stories can encourage us to take risk. (A general failing of neoclassical economics is its incuriosity about genealogy). It also presumes that preferences are a guide to our future happiness. But as Merkle has shown, this is not the case: where there is noisy (or plain bad) coding, our preferences need not fulfil our interests.

What looks like an arcane area of economics is therefore central not only to how we behave in important respects but also to some of the shortcomings of neoclassical economics.

January 29, 2021

The death of economic policy

One of the great and under-appreciated changes of recent years has been the disappearance of serious economic debate from Westminster politics.

For decades the big political divide was about economics: the causes and cures for the UK���s relative economic decline; the precise mix of state and private sector; what to do about industrial relations; monetarism vs Keynesianism; how to achieve macroeconomic stability; how to redefine social democracy in the 90s; and austerity after 2010.

Today, though, mainline politics is largely innocent of economics. The Tories, Stian Westlake has said, ���seem to have stopped talking and thinking about economics.��� We see this, for example, in the decline of John Redwood from being a serious Thatcherite to a sub-North Korean driveller about juche. More starkly, it was once inconceivable that any Tory would utter the phrase ���fuck business��� ��� let alone become Prime Minister having done so.

It���s not just Tories, though, who have abandoned economic thought. So too have centrists. The TIG (or whatever they called themselves) were silent on economics except for waffle about fiscal responsibility. And Chris Leslie���s Centre Ground pamphlet (pdf) said nothing about how the financial crisis requires us to rethink economics, despite his boast that centrism chooses ���an evidence-based rather than ideologically-driven approach to the world.���

I fear that Labour might go the same way, and lose its McDonnell-inspired interest in fundamental change of our economic institutions.

There is a justification for this lack of interest. Raising medium-term economic growth is hard: in fact, growth rates might well be determined more by international factors than local ones. And it���s not worth the effort. You don���t have to subscribe fully to the Easterlin paradox to suspect that economic growth doesn���t translate into great improvements in well-being; the fact that well-being seems to have improved in recent years despite our sclerotic economy is consistent with this.

What���s more, many important issues can be addressed without policies to raise general economic growth ��� such as food poverty, the housing crisis or climate change.

You might add a further justification for the declining importance of economic policy. It���s that voters don���t care about it. As Stephen Davies says in The Economics and Politics of Brexit, that "the main division in society has switched from being primarily about economics to being about culture and identity��� ��� that there has been a realignment in politics along cultural lines.

These, I suspect, are justifications rather than reason. Voters��� attitudes are not exogenous. They are instead the product of both economics (stagnation tends to breed reaction) and of political forces ��� the way in which eurofanatics forced what was once a fringe issue to the top of the agenda.

Instead, I suspect there are two reasons for the loss of interest in economic policy.

One is that centrists and the right just don���t have a clue.

From the 70s to 2008, the question for neoliberal economic policy was how to unleash capitalism���s incipient dynamism. Whether it was Thatcher blaming the unions or high inflation or Brown blaming unstable macro policy, politicians thought that the role of government was merely to create the right conditions for growth and that capitalism would then deliver it.

Subsequent events have refuted this view. The 2008 crisis showed that lightly-regulated capitalism was unstable. And weak trend growth since then suggests that governments might have to intervene more in the economy to stimulate growth. Not having answers to these problems, the centre and right have gone quiet.

Secondly, there are fewer interests that are served by economic growth. As Brett Christophers has described, the economy is dominated by rentiers. Their wealth depends less upon revenue growth and more upon maintaining and securing rights to assets, sometimes via cronyism. It���s not just companies for whom this is true. Many retired pensioners with expensive houses are in the same position.

In fact, for many of these, economic growth might actually be a bad thing. Sustained strong growth would raise real interest rates. But this would depress asset prices by raising the discount rate applied to future rents and by increasing the cost of leverage. Fordist capitalism required a large and growing mass market; rentier and financialised capitalism do not.

Perhaps, though, politicians were never really that interested in promoting growth even when they claimed to be.

Sure, they all talked about the UK���s relative economic decline in the 50s, 60s and 70s. But maybe this was less because they wanted to raise living standards and more because they feared the UK���s loss of power and prestige on the global stage. And if they did care about raising living standards it was less out of concern for workers��� well-being and more out of the desire to buy off discontent ��� to show, in the face of the communist threat, that capitalism could deliver the goods.

And perhaps Thatcher���s assertion of ���managers��� right to manage��� was not a means of increasing efficiency but rather a desire to impose traditional hierarchies and put workers back into their subordinate place. As Corey Robin has argued, the one common theme in conservatism is its love of hierarchy.

Traditionally, Marxists have thought that capitalists need economic growth. Which is true of capitalism operating within markets. But it is not true of all types of exploiters: feudal lords did perfectly well for themselves in stagnant economies. Perhaps, then, the loss of interest in economic policy is a symptom of the fact that capitalism today in fact is characterised by powerful elements of feudal exploitation. Rightist and centrist politicians are no longer interested in economics because they no longer need to be.

January 24, 2021

Endogenous policy

In a justly criticised piece in the FT, Morgan Stanley���s Ruchir Sharma says:

My team also found a statistically significant link between periods of rising government debt and slow GDP growth. These studies cannot show causation, but the consistent link between growing deficits and weakening growth is unlikely to be coincidence.

True, it���s unlikely to be coincidence. What is likely, though, is that the causality runs from a weak economy to rising government debt. Slow growth causes rising government debt not just because it depresses tax revenues and raises welfare payments but also because it causes governments to loosen policy.

Sharma���s failure to give due weight to this obvious possibility is an egregious example of a widespread error ��� an inability to appreciate that policy is endogenous. This arises from the very language of economics. We tend to speak of policy as ���interventions���, as if policy-makers were outside the economic environment, stepping in only to meddle or to correct a market failure (delete according to ideology). But in fact, policy-makers are an inescapable part of the environment, and their beliefs and actions are influenced by it and vice versa.

Another example of this type of error is when it���s said ��� often by a type of Austrian economist ��� that QE and zero interest rates have pushed asset prices up to ���artificial��� levels, as if policy were an unnatural deviation. But this is wrong on two counts. For one thing, the only prices that matter are those at which assets actually change hands; it is your imaginary counterfactual world that is artificial. And for another, it���s likely that policy measures to reduce interest rates only reflect economic forces such as low growth and capitalists��� reluctance to invest.

That error reflects a wider and longer-standing one ��� one that dates back to Smith���s claim that humans have a natural ���disposition to truck, barter, and exchange���. It���s the idea that markets are natural and thus that interventions are unnatural. But this is not the case. Markets were, wrote (pdf) Polanyi, ���incidental to economic life��� before capitalism, and a market society is, wrote David Graeber, a ���relative newcomer.���: Ellen Meiksins Wood is also good on this. There���s nothing artificial about state involvement in the economy; it���s been going on for centuries.

It���s not just people with daft ahistorical ideas about markets who fail to see the endogeneity of policy. Here are some other examples.

1. A few years ago, the Independent ran a series in which people said what they���d do if they were PM. This told us plenty about the writers, and nothing about politics. The Prime Minister and his policies don���t fly in from outside to rescue us like the Thunderbirds. They are the outcome of socio-economic structures that select for policies and individuals, and not necessarily the best.

2. Sarah O���Connor describes how ���some benefits of a higher minimum wage can leech away in an under-regulated labour market��� as employers cut overtime pay or hours or simply fail to comply with it. What this omits is that such under-regulation is no accident. It���s endogenous ��� a consequence of the power of capital to resist what few demands there are for tighter labour market regulation.

3. Several recent books, such as Lindsey and Teles��� The Captured Economy, Case and Deaton���s Deaths of Despair and Thomas Philippon���s The Great Reversal describe the rise of rent-seeking and cronyism in the US and advocate policies to counteract it. It is, however, wrong to think that rolling back cronyism is merely a matter of policy-makers knowing what to do. It also requires a favourable balance of class power. And right now, (some) capitalists have the power (pdf) to bend government to their will. Crony capitalism is endogenous ��� the result of capitalist power. Reversing it significantly requires a diminution in that power.

4. Donald Trump did not become president because Americans suffered a collective knock on the head from which they recovered last November. His popularity is instead the result of socio-economic conditions. The ���white anxiety��� which he exploited is, says Jonathan Metzl, ���a problem, not just of individual minds or attitudes, but of larger social and socioeconomic structures.��� Part of the story here is that these structures contributed to industrial decline and a loss of income and status among some voters. Trumpism, says Samuel Farber, is ���a right-wing response to the objective conditions of economic decay.��� And, adds Branko Marcetic, it is ���the logical, some would say predictable, product of the failures of not just Barack Obama, but decades of neoliberal politics.��� Back in 2006 Ben Friedman showed that economic stagnation fuelled racism, intolerance and anti-democratic sentiment. Trumpism vindicates that view. Unless these socio-economic conditions are significantly changed, we risk seeing a re-emerging of some form of Trumpism.

My point here is to challenge a particular view of politics which is perhaps widespread among centrists. It���s the belief that we could have better policies if only we were governed by people of intellect and goodwill. But this misses a big fact ��� that actually-existing capitalism tends to militate against good government by, for example, promoting cronyism, managerialism and reaction and selecting against technocrats. Liberal, technocratic government requires that we challenge capitalism.

January 20, 2021

Character, context and work

It is fitting that Donald Trump should leave office in the same week that Phil Spector died, because both remind us that the quality of a man���s character is not the same as the quality of his work.

As a human being, Mr Trump recalls the words of the great Fred Thursday: he���s worth nowt a pound, and shit���s tuppence. As a president, however, his performance wasn���t quite as disastrous as his character. He didn���t start any new wars (though he did continue old ones); broke the confines of fiscal orthodoxy; (marginally) reformed the awful criminal justice system; and showed an awareness that millions of Americans were let down and alienated from conventional politics. Of course, there���s huge downsides too ��� on immigration policy and climate change not to mention the mishandling of Covid (though the awful handling of Hurricane Katrina suggests he���s not the first president to horribly fail during a natural disaster.)

My point here, though, is not really about Trump. It is that we cannot judge a man���s work by his character. Phil Spector exemplifies this much better than Trump, producing great music whilst being utterly reprehensible as a person. And of course he is just one of a long line: think of Richard Wagner, Eric Gill, Woody Allan, Jimmy Donley, William Shockley, Steve Jobs and so on. So much so, in fact, that it has long been a clich�� that we must separate the man (less so the woman) from the work.

What���s going on here? It���s not that genius requires drive and selfishness that are only found in monsters. Good people can be geniuses too: think of David Bowie, Duke Ellington, Thomas Hardy or Jane Austen.

Instead, what matters is context. Had they not gone into politics, Stalin would have been just a failed seminarian and Pol Pot an average engineer.

Herein lies an under-appreciated merit of markets. When they work properly the make bad people do good things. As Adam Smith said,

It is not from the benevolence of the butcher, the brewer, or the baker that we expect our dinner, but from their regard to their own self-interest. We address ourselves not to their humanity but to their self-love, and never talk to them of our own necessities, but of their advantages.

There are tens of thousands of greedy, psychopathic narcissists in the world, and market forces compel them to serve the social good.

I���d add an indirect benefit of markets. In providing affluence and innovation they give more people more ways to develop and demonstrate their genius. Without a film industry Woody Allan and Roman Polanski would just have been nonces. And without a music business Phil Spector would just have been a psychopath.

But of course, well-functioning markets are only one of many things that mediate character and outcomes. Another was recognised by Marx:

Capital is reckless of the health or length of life of the labourer, unless under compulsion from society.

Which is why capitalism worked best in the post-war period, when social norms and trades union power mitigated exploitation.

Here, we might contrast Trump with one of his predecessors, Lyndon Johnson. As a man, Johnson shared Trump���s crassness and was perhaps even more racist. And yet in getting the Civil Rights Act passed he did more for racial equality than many presidents. Why? In part, because he was under compulsion from society: he���d not have done it if it had been a vote-loser.

By the same token, much of what we dislike about Trump���s presidency reflects social pressures. His anti-migrant policies for example have been popular; his mishandling of Covid might be a reflection of a lack of state capacity; and his racism, conspiracy theories and contempt for the truth resonate with millions of Americans.

We���ll wake up tomorrow with a new president. But we���ll also wake up with the same longstanding American problems: racism; capitalist stagnation and the intolerance that it breeds; chronic inequality; neoliberalism; cronyism; and the strength of the military industrial complex. It is these that shape policy, more so than good or bad men.

All good businessmen know that every bad employee is a bad hiring decision. The same is true in politics. Rather than persist in a simplistic moralistic search for heroes and villains we must ask how to change politics and society so they either select against the likes of Trump or at least channel nasty impulses towards more useful purposes.

January 17, 2021

Debates, fake and genuine

There might not be any general purpose experts, but there are general purposes idiots. That���s one inference from Ipso���s ruling that one of Toby Young���s Covid denialism columns was ���significantly misleading.���

In fact, though, this episode tells us something more general about the nature of capitalist power.

The thing is that Young is not an isolated fool. There is a small industry of Covid-deniers, as Neil O���Brien (one of the few Tory MPs brave enough to make a pubic display of intelligence) reminds us. Which poses the question: why do people with no knowledge of medicine or epidemiology feel the need to jump in with silly takes?

It���s because they have an incentive to do so: there���s a demand for gobshites. And it doesn���t come only from trash media such as talkRADIO or the Telegraph. It also comes from the BBC. Only a few days ago, for example, it invited Young onto Newsnight despite the fact that events have discredited his spewings on Covid.

Patrick Howse blames this on the BBC���s ���erroneous pursuit of balance���:

Instead of actually trying to establish the truth, BBC News programmes often now content themselves with merely presenting different ��� usually extreme ��� points of view. And it doesn���t seem to matter tremendously whether these opinions have any basis in reality or any evidence to back them up.

Janan Ganesh says one reason for this lies in the rise of 24-hour news with its need to fill airtime:

TV producers are bound by the imperative to fill time. The contrived debates, the tendentious guests from campaign groups, the ���engagement��� with viewers: the aim here is to populate a schedule, not to cretinise or incite���.TV news established the idea that what matters about an event is its contested meaning, not its core of facts.

I���m not sure about this, though. The are lots of useful debates to be had about our response to Covid. For example, how do we trade-off mental against physical health and what can be done to mitigate the adverse impact of lockdowns upon the former? How do we value lives and thereby assess the costs and benefits of lockdowns? What types of behaviour are most likely to spread Covid and do the benefits of these activities really outweigh the costs? What can be done to mitigate the economic impact of Covid, and how reasonable is it to shift the burden of doing so onto future generations? And so on. We don���t need grifters to discuss these: we can use health experts, economists and philosophers.

In principle, broadcasters and newspapers could fill space intelligently.

The point of course, broadens. There are loads of debates the media could be having which aren���t ��� or at least which are not filling up enough space. Such as: why have productivity and real wages flatlined since 2007? Is this because of the failure of capitalism, or of economic policy, or what? And what can be done about this? Have we seen a decline of productive entrepreneurship and rise of rentierism and cronyism and if so why? Why are the government���s borrowing costs so low? What are the constraints upon fiscal policy? Why is it drivel to say the government���s credit card is ���maxxed out���? Does the government even have a right to exclude migrants? Is there a case for open borders? Why are bosses paid so much? Is there a case for a maximum wage? Should we have a citizens��� basic income? Should the tax base be moved from incomes to land or consumption? Is there a case for worker ownership and if so what form should it take?

And so on and so on. You can all add to this list.

The point is that even if we concede that the media must fill space with debate, it could do so in a very different way than it actually is. In theory, we could have phone-ins along the lines of: how bad are your working conditions? Is your boss mismanaging your firm? Instead, we get blowhards spouting off about things they don���t know.

But we don���t get such debates ��� and they certainly do not dominate the agenda in the way that Brexit has or the culture wars threaten to do so.

Why not? You might say it���s because audiences don���t want such debates. True. But this misses the point that before 2015 people weren���t much interested in the EU either: in 2015 less than 10% (pdf) of people thought it the important political issue. It became prominent because a handful of cranks manipulated the BBC into making it a big issue.

Which is where capitalist power comes in. Such power does not consist merely in overt shows of force or bribery. It also consists in manipulating the agenda ��� deciding what questions get debated and what don���t.

In fact, it also consists in something else - in subtle and emergent ways in which people accept capitalist injustices and inefficiencies ��� what John Jost calls system justification (pdf) ��� and so don���t even ask about those injustices.

This acceptance is not created by the media: people acquiesced in injustice long before the mass media came along. But the media does amplify it by its decisions on what gets debate and what doesn���t.

And these decisions are not consciously made to defend capitalism. One reason why we don't get the debates I'd like is because the news by its very nature under-reports slow-moving trends - even though it is these, much more than day-to-day events, which shape our lives.

But the collective, emergent, upshot of these editorial decisions is to bolster an unquestioning acceptance of capitalism. As Steven Lukes wrote:

Is it not the supreme and most insidious use of power to prevent people, to whatever degree, from having grievances by shaping their perceptions, cognitions and preferences in such a way that they accept their role in the existing order of things, either because they can see or imagine no alternative to it, or because they see it as natural and unchangeable? (Power: A Radical View, p28)

Yes, you are all right to decry the attention given to Young (and Hartley-Brewer, and Grimes, and so on). But this attention is the product of an emergent system which functions to deflect attention away from the failings of capitalism. It is, in this sense, yet another symptom of capitalism���s dyfunctionality.

January 13, 2021

On forecasting

What���s the point of forecasting? This is the question posed for me by Michael Story���s account of superforecasters��� predictions for the course of the pandemic.

Take this:

Our central estimate that the death toll will peak at 1,278 with an 80% confidence interval of 892 to 5,750.

So what? It���s not all clear how this affects the debate about how tight the lockdown should be. That depends upon how the virus is transmitted; the trade-off between mental and physical health; how far the economic effects of the lockdown can be mitigated; and so on. Yes, that claim that the daily death toll could be 5750 is alarming, and speaks to the need for a tight lockdown. But you don���t need any precise number to make that case. The mere chance of a high death toll does as well.

Similarly the forecasters��� 80% confidence interval that between six and 20 million people will be vaccinated by end-February is also irrelevant for policy. What matters is that the vaccine is delivered to as many people as possible. That���s a matter of logistics, not of forecasts.

If the forecasts are irrelevant for policy, what use are they?

Yes, if you���re spread-betting on the final death count, they might be useful. But few of us are doing this. And anybody who is faces the problem that superforecasters��� views should in theory get quickly embedded into prices. Which means that by now they don���t help us beat the market. We���re no better off.

Another potential use of forecasts is that they test hypotheses: a correct forecast should strengthen our confidence in the theory upon which it rests, whilst a wrong forecast should weaken it. We must therefore always ask of a forecast: was it right or wrong, and if so why and what do we learn from this? as Jonathan Portes does here and I did here.

But again, it���s not obvious how the superforecasters help us in this respect. Let���s say we see low numbers of vaccinations, so the superforecasters are wrong. What hypothesis is then weakened? Sure, faith in the government���s logistical ability would be ��� but we don���t need superforecasters to assess this, merely progress in vaccination against the government���s own targets.

My reaction to this piece, then, is the same as that to very many forecasts, such as those for November���s US presidential election: there���s no point to them, as we���ll find out soon enough anyway.

In fact, for me, exercises such as this miss four more interesting issues in forecasting.

First, is there any predictability in human affairs, and if so what is its origin?

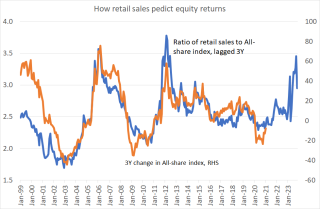

Take for example, my chart. It shows that medium-term returns on UK equities have been highly predictable by a simple ratio of retail sales to the All-share index: this ratio predicts decent returns over the next three years (as I say, a forecast should be a test of a hypothesis).

This measure works for two reasons. First, consumer spending is, partly, forward-looking: if we anticipate good times we���ll spend more than if we anticipate bad, and on average across millions of consumers forecast errors largely cancel out. Secondly, equity investors do not fully price in this wisdom of crowds, causing equities to be under-priced when retail sales are strong relative to share prices. (For more sophisticated versions of this theory, see Lettau and Ludvigson (pdf) and this paper from the Bank of England).

What we have here, then, is evidence of predictability and a reason for it. What are the analogues of these in other domains?

Secondly, who are the best forecasters: foxes (who know many things) or hedgehogs (who know one thing)? Philip Tetlock argues that foxes do better. This is not true in all domains, however. In my example, the hedgehog who looked only at the retail sales to All-share ratio would have done better than foxes who tried to process all possible information about prospective market returns. Also, if you want to know the chances of a recession, a single glance at the yield curve does far, far better than economists��� foxier forecasts. What works in one context doesn���t work in another.

Thirdly (and perhaps relatedly): do forecasts change the environment or not? Most of those discussed by Tetlock do not: this is true of the Covid forecasts as well. Other forecasts, however, do. Optimistic forecasts for (say) where Bitcoin or Tesla shares raise their prices today and hence reduce future returns. Investor sentiment ��� which is correlated with share price forecasts ��� can predict future returns.

In such cases, we need a different approach. We should ask not: ���what will happen?��� but ���what information (if any) are market participants ignoring?��� To use a useful anology in Meir Statman���s Finance for Normal People, superforecasting is a game you play against the environment whereas investing is one you play against other investors. These are different things.

Fourthly, do we need forecasts at all? Sometimes we don���t. I���ve shown that investors who diversified very simply have done perfectly well without forecasting anything. In the same spirit, the stock-picker who simply bought momentum or defensive (pdf) stocks would over time have out-performed those who tried to forecast returns for individual stocks or the market.

In other contexts, what matters is not a point forecast but rather the distribution of possibilities. The case for zero interest rates isn���t based on a particular forecast, but upon the balance of risks: there���s a risk of sustained high unemployment but less risk of soaring inflation.

The best policies should not rest upon a forecast. For example, a basic income can and should be justified on many grounds other than that we need one because automation will destroy jobs (maybe it will, maybe it won���t). And one reason why we need stronger counter-cyclical automatic stabilizers is that we cannot rely upon a predict-and-control approach to macro policy.

Now, I don���t say all this to attack superforecasting. Mr Story is bang right to say that bad forecasters should be driven out of the marketplace of ideas: the fact that they are not is because of perverse incentives in the media. And a lot of advice on how to be a better forecaster is valuable as advice on how to think better.

Forecasts are perhaps the least interesting part of the superforecasting project.

January 9, 2021

On fantasy politics

One of the great political divisions today is between those who acknowledge reality and those whose politics derive solely from the voices in their head.

After Trumpites stormed Congress earlier this week Ian Austin tweeted that ���I don't believe the hard left would have accepted an election defeat��� ��� ignoring the fact that only 13 months ago the left did indeed accept Labour���s defeat peacefully.

And then Matt Goodwin tweeted:

Johnson is socially liberal at heart, Trump is authoritarian. Johnson is instinctive free trader, Trump is protectionist. Johnson is pro-migration at heart, Trump is xenophobe.

Again, this is untethered to reality. As mayor of London, Johnson banned alcohol on the tube and tried to use water cannon on protestors; he was a member of the government that pursued the hostile environment policy; and his Brexit deal erects trade barriers.

We can add to this Andrew Neil���s claim that ���academia today is often more interested in closing down debate than encouraging free speech���, which echoes the right���s largely deluded (and certainly hypocritical) obsession with cancel culture; anybody past the age of 21 who���s interested in student politics needs to give their head a wobble,

What���s going on here is more than just normal political lying, which at least can serve the function of getting one out of a tight spot or advancing a policy you might advocate on other grounds. It���s a gratuitous denial of basic reality.

In my formative years, the right wanted lower taxes and weaker unions ��� demands which had at least some connection to facts. Today, they fantasize about cancel culture and promote Covid denialism; their American counterparts are of course even more barking.

Which poses the question: why is post-truth politics so widespread?

Of course, we all retreat into fantasy when reality is uncomfortable. Michael Oakeshott saw this. In his classic essay, On Being Conservative (pdf) he describes the conservative inclination as being an empirical one:

To be conservative���is to prefer the familiar to the unknown, to prefer the tried to the untried, fact to mystery, the actual to the possible.

But, he said, ���If the present is arid, offering little or nothing to be used or enjoyed, then this inclination will be weak or absent.���

And from a rightist point of view, the present is indeed arid. There are, I suspect, three aspects of reality that are forcing many on the right and centre into these fantasies.

Phil points out one ��� that right-wing politics, at least in its current form, is living on borrowed time:

Conservatism and right wing politics presently constituted are in long-term decline. Social liberalism is the commonsense of the rising generation, and as older people pass on the cap doffing, imperial nostalgia, and anti-social bloody-mindedness is not getting replaced like for like. The consequence is in the medium to long-term the eventual diminishing of the audience for their wares - despite the explosion of rightist outlets and a pantheon full of interchangeable atavists. Banging on about leftists and cancellation is an expression of their terror for an irrelevant future, a manifestation of the threat they feel in their marrow.

A second is that much of the right suffers a cognitive dissonance. On the one hand, they like to think of themselves as freedom fighters but on the other hand hard facts show that it is the left that���s on the side of freedom and the right of repression. So-called ���libertarians��� such as Desmond Swayne oppose drug legalization and the Tory government has pushed through a bill permitting the security services to break the law in the face of opposition from the left. The right���s response to this dissonance has been to invent stories of how the left is oppressing them.

Thirdly, (neoliberal?) capitalism is failing. The financial crisis taught us that light regulation does not ensure stability or growth. And productivity ��� and therefore wages ��� has stagnated for almost 15 years. Exactly why this has happened is a matter of debate among economists. Possible causes include: investment being depressed by a fear of future innovation; a falling rate of profit; scarring (pdf) effects upon animal spirits of the 2008-09 recession; the long-term effects of high inequality; firms��� realization that innovation and investment don���t pay; the rise of rentierism squeezing entrepreneurial profits; a slowdown in the rate of innovation; falling productivity of R&D and so on.

The point is, though, that Tories (and centrists like Austin too) are ignoring this debate. As Stian Westlake has said, ���the Tories, both in government and more generally, seem to have stopped talking and thinking about economics.��� Their response to the crisis of capitalism has not been to try and fix it, as Thatcher did, but to deny that it exists ��� to either pretend that Brexit will unleash a new golden age or to retreat into culture wars.

Now, this is not to say that all Tories have lost touch with reality: Jesse Norman and Neil O���Brien, to name two, are still connected with it. Instead, the point is that the rightists haven���t collectively suffered a bang on head. They have retreated from reality because in some respects that reality is unpleasant for them.

Chris Dillow's Blog

- Chris Dillow's profile

- 2 followers