Chris Dillow's Blog, page 13

June 1, 2021

Full employment, capitalism - and beyond

Is genuinely full employment possible? And if it is, is it compatible with capitalism? These are questions raised by President Biden���s ambition for an economy where ���employers have to compete for workers.��� This, he hopes, will ���give workers more ability to earn a higher wage��� and ���the power to demand to be treated with dignity and respect in the workplace.��� This, he claims, ���isn���t just good for individual workers, it also makes our economy a whole lot stronger.���

This might not be a purely American question. James Meadway has argued that a world of ongoing pandemic risk ���is one in which the balance of power at work can shift dramatically back in favour of labour.���

Certainly, there���s a precedent for por-worker policies making economies a whole lot stronger. In the 50s and 60s western economies had fullish employment (for men at least). And profit rates and equity returns were good: the S&P 500 for example delivered a real total return of 9.1 per cent per year between 1952 and 1972, which is even better than it has done in the last 20 years.

There are good reasons for this. Because workers tend to spend more of their income than billionaires, transferring cash to them can boost demand. The assurance of high demand can encourage firms to invest more. And the prospect of rising wages should incentivize them to invest in labour-saving technologies ��� things which can boost productivity. Through these mechanisms, everybody wins. This is what Marc Lavoie and Engelbert Stockhammer call wage-led growth (pdf).

But can we really return to the 1950s? One reason for thinking so is that anti-labour policies and low taxes in most developed economies have led to slower growth in both output and productivity. This fact, say ��zlem Onaran Giorgos Galanis, suggests that wage-led growth is possible (pdf).

I have my doubts, however. As Steven Marglin and Amit Bhaduri ��� and the bitter experience of the 1970s crises - showed, cooperative capitalism is only one possibility (pdf). It is also possible that full employment will squeeze profit margins and depress animal spirits and investment, resulting in lower growth and the end of full employment.

The first thing to note here is that the full employment Biden has in mind is very different to that of the 50s and 60s. Back then, aggregate demand was high largely because of high private sector demand, in part because the war had created a backlog of demand for civilian capital goods; the federal budget was in rough balance for much of this time. Biden���s ambition for full employment by contrast is founded upon an expansion in public investment. That���s an admission that in a world of capitalist stagnation, the private sector won���t get us to full employment.

It���s theoretically possible, however, that public spending will stimulate private investment via accelerator effects.

There is, however, an offsetting mechanism. It���s that neoliberalism is performative; it creates behaviour as much as describing it. For the last few decades the ruling ideology has been that low wages and low taxes are business-friendly. Capitalists might well therefore regard a world of rising wages and higher taxes as a scary prospect, and so they���ll depress animal spirits and capital spending. Also, whilst in the 50s and 60s businesses had the technical skills to replace labour with capital, these skills might well have been lost after years in which the question for businesses has been of how to exploit cheapish labour: ���robots taking jobs��� is something which is much more discussed than observed ��� as indeed, the productivity stagnation demonstrates. Sustained high aggregate demand, then, might not be sufficient to kick-start productivity growth.

There���s another reason for doubt. Remember a basic national accounts identity for profits. By rearranging the facts that GDP is equal to both the sums of expenditures and incomes, we get:

P = (C ��� W) + I + (G ��� T) + NX.

This tells us that if consumption (C) rises as much as wages then ��� ceteris paribus ��� profits (and indeed the share of profits in GDP) don���t change. What capitalists lose in high costs they recoup in higher revenues.

For much of the 50s and 60s this was indeed the case. In the early 70s, however, C grew more slowly than W and so profit margins were squeezed: this was more pronounced in the UK than US. I fear this could happen again if workers use higher wages to reduce debt or simply if those higher wages result in the government clawing back tax credits. (There���s also the issue that, with economies more open now than in the 50s and 60s, higher wages will leak more overseas in the form of increased imports rather than domestic demand.)

Even if all my doubts are wrong, however, there���s another problem: do capitalists really want full employment even if it is compatible with decent profits?

One problem here was famously described (pdf) by Michal Kalecki:

Under a regime of permanent full employment "the sack" would cease to play its role as a disciplinary measure. The social position of the boss would be undermined and the self assurance and class consciousness of the working class would grow. Strikes for wage increases and improvements in conditions of work would create political tension. It is true that profits would be higher under a regime of full employment than they are on the average under laisser-faire���But "discipline in the factories" and "political stability" are more appreciated by the business leaders than profits. Their class instinct tells them that lasting full employment is unsound from their point of view and that unemployment is an integral part of the " normal " capitalist system.

The other problem is that recent years have in the UK and US seen a big increase in the influence of finance capital relative to that of industry. And whilst full employment might have been good for General Motors (it increases demand for cars) it is not so good for Goldman Sachs. Finance capital requires low interest rates both to support asset prices and to render profitable strategies of ���picking up pennies in front of a steamroller.��� Low rates, however, require a sluggish economy.

We���re already seeing fears of higher inflation, in the UK and US. Economists reply to this that there���s a simple solution to higher inflation ��� to raise interest rates or reverse QE. Technically, this is correct. But it ignores the class aspect ��� that higher rates jeopardize some powerful interests. And it also ignores the fact that higher rates reduce inflation precisely by increasing unemployment. We could square this circle by tolerating higher inflation; as Servaas Storm says, wage-led growth requires (pdf) loose fiscal and monetary policy. But one lesson of the 70s is that higher inflation can itself kill off full employment, not least by creating uncertainty.

Biden���s hopes for full employment are therefore a bold experiment. But what if they fail?

The answer is not to retreat back to regressive neoliberalism. Instead, as Marglin and Bhaduri concluded, we must ���recognise the ultimate desirability of making accumulation independent of profitability���. As William Beveridge wrote in 1944:

If���it should be shown by experience or by argument that abolition of private property in the means of production was necessary for full employment, this abolition would have to be undertaken. (Full Employment in a Free Society, p23)

Mainstream economists have long forgotten this ��� if indeed they ever knew it ��� and have discussed employment and inflation on the implicit assumption that capitalistic ownership is immutable. But it needn���t be. James Meade and Martin Weitzman, for example, thought the solution to the collapse of wage-led growth was to introduce a big dose of profit sharing between capitalists and workers. As long as firms��� aggregate revenues ��� wages and profits combined ��� are growing well, they (only might) have an incentive to expand.

Of course, a lot of work needs doing on the precise form such post-capitalistic ownership structures will take: it���ll vary from industry to industry and country to country. And it poses the question: what function do capital-owners actually fulfil?

But that���s my point. Biden���s talk of fiscal expansion, higher minimum wages and full employment shows that the left has won a lot of intellectual battles. But the ultimate battle ��� about who should own companies and how ��� has barely even started.

May 29, 2021

Playing the victim

Here are four recent developments:

- The University of Leicester is sacking academics because they are doing research in critical management studies. The Tories, however, are silent on this whilst at the same time condemning a handful of students who are unsuccessfully campaigning to get Eric Kaufman sacked from Birkbeck. They tolerate actual violations of academic freedom whilst deploring attempted ones.

- Laurence Fox calls for the Leicester City players who carried a Palestinian flag after the FA Cup final to be hounded out.

- Matthew Offord MP demands that the BBC not broadcast an edition of Desert Island Discs because of Alexei Sayle���s ant-Zionism.

- Several people complained to the police about a tweet from an SNP councillor about the Eurovision song contest.

These are all examples of how the right (and bosses) are opposed to free speech. And of course there are countless other examples of Tory hostility to freedom such as their harsh immigration controls, clampdown on protests and erection of trade barriers within the UK.

And yet these attacks upon freedom come from people who claim to be champions of free speech and protectors of academic freedom. They present themselves as victims of repression, beleaguered by ���wokesters���, ���not allowed to say that these days���, and subject to no-platforming. Oliver Dowden, for example, recently whined about a ���cancel culture whereby a small but vocal group of people claim to have the monopoly on virtue, and seek to bully those who dare to disagree.��� In this, way, as Will Davies said:

A reader of the Times or the Daily Mail can convince themselves that they are a marginalised minority.

It���s not just in the context of free speech that the right makes this pretence. They also claim to be victims of ���EU bullies���.

This is strange. Traditionally, political movements and politicians have wanted to project power: think of things as otherwise diverse as the Nuremberg rallies; Thatcher rejoicing in the nickname ���the iron lady���; the classical Marxian hope that the working class would grow strong enough to overthrow capitalism; Black Power; gay pride; Blair and Brown���s endless talk of ���strong leadership���; or leftists boasting of the number of people on large demos. What we have here is the exact opposite ��� a claim to weakness by those who in fact are in power. We have Harry Flashmans masquerading as Tom Brown.

What���s going on here?

In part, it���s that old saying: ���when you���re accustomed to privilege, equality feels like oppression.��� As Dawn Foster says, the right think free speech means the right not to be criticized. They are perturbed to find previously marginalized people and perspectives challenging their own viewpoint and their historical myths.

More troubling for them is the sense that these challenges are the shape of things to come. The right���s voting base is greying and dying whilst the future will be that of immaterial workers and graduates sympathetic to socialism; Tories are less rooted in statecraft and with the elite than they used to be; and the party has lost serious intellectual foundations (Thatcher had Popper, Hayek and Friedman: who has Johnson got?). Of course, there right are in power now, but this power is brittle.

And its pretence of victimhood serves to shore up such power. It effaces inequalities. Men can pretend they are oppressed by feminism and white people by ���critical race studies���, thereby denying the realities of gender and racial inequality.

And, of course, class inequality. The idea that privileged people are being bullied by wokesters and eurocrats has allowed public schoolboys like Johnson and Farage to pretend to be men of the people ��� even though the latter is so weird he doesn���t listen to music or watch TV. The revolt against elites has merely facilitated the rise of another elite.

The art of bourgeois politics has of course always been to hide the true nature of inequality. What is remarkable is just how many ways those in power have of performing this trick.

May 20, 2021

Starmer, skill and luck

Why is Sir Keir Starmer making such a mess of being Labour leader? A good perspective on this comes from a 2006 article (pdf) in the Harvard Business Review by Boris Groysberg and colleagues: I fear most journalists and Labour activists have overlooked this because the HBR is too left-wing for them.

They looked at what happened when senior managers at General Electric became CEOs of other companies. And they found that bosses with similarly impressive CVs had hugely different performances in their new firms. This, they say, is because what matters is not so much the individual boss���s skills but the match between those skills and the job requirements. So if for example a cost-cutter took over a firm whose priority was to grow rapidly, he failed, whereas he succeeded if he took over a firm that needed to cuts costs in order to undercut its competitors.

Starmer���s problem is that whilst there was a good match between his skills and the job requirements of being Director of Public Prosecutions, there is a less good match between them and what it takes to be a good Labour leader. As DPP one can occasionally get away with dumping blame upon an underling, but this is harder for a Labour leader especially when those underlings have a significant powerbase and mandate of their own. More importantly, a DPP needs mainly to just keep the organization running. He doesn���t need a vision with which to inspire waverers. But a Labour leader certainly does. To use Groysberg���s framing, moving from being DPP to Labour leader is like moving from running a monopolistic utility to a growth company needing to catch customers��� attention in a competitive environment. It���s no surprise that a man can succeed at one but fail at the other.

Of course, there���s nothing at all unusual in a man being a good fit in one job and a bad one in another. It is the story of many football managers: Jose Mourinho was a great fit with Chelsea at least in his first spell there but not so much at Sp*rs, for example. Many successful businessmen who go into politics have mediocre careers. And countless men are geniuses in one field but fools in others: think of Bobby Fischer, William Shockley, James Watson, Richard Dawkins���

You might object here that this assessment of Starmer is founded upon hindsight.

Damn right it is. And that���s the point. We often cannot tell in advance who will be the best fit for the job ��� which is why so many hiring decisions go wrong. As William Goldman famously and rightly said, nobody knows anything.

We should therefore change our frame. Success can be the product not of skill and intention but of the luck of being the right person in the right place at the right time. Think of politics and indeed business as being like natural selection: randomish chances spring up ��� particular individuals, companies or strategies ��� and the environment selects for and against these. For example, whilst they were MPs it was not at all obvious that Boris Johnson would make a more successful Prime Minister than Theresa May ��� which is why Tories voted her leader in 2015. But he has, because the environment has selected for his mix of strengths and weaknesses whilst it selected against hers. (Whether this will remain the case is, of course, another matter.) To take another example, John Denham says the Tories have ���managed extraordinarily well to appeal to English-identifying voters". He's right. But Tory appeals to nationalism failed abysmally in the late 90s and 00s, so why are they succeeding now? Could it be because the environment that once selected against such appeals now select for them?

People are, however, terrible at distinguishing between luck and skill. The most striking evidence for this comes from experiments by Nattavudh Powdthavee and Yohanes Riyanto. They got students in Singapore and Thailand to bet upon tosses of a fair coin and found that they were willing to pay to back the bet of students who had correctly called previous tosses. ���An average person is often happy to pay for what could only be described as transparently useless advice��� they concluded. Startling as it seems, this has been corroborated by other experiments.

And people make this error even when they have real money at stake. Investors around the world (pdf) lose money because they buy unit trusts that have performed well for a few months, failing to see that short-term returns are largely due to luck. They ���confuse risk taking with skill��� says Christoph Merkle. They ���lose money because they buy unit trusts after short periods of good performance, failing to see that this can be due to dumb luck rather than to fund managers��� skill��� say Andrew Clare and Nick Motson at Cass Business School.

Most fund managers are not skilful ��� but some get selected for by the luck of the environment. Maybe the same is true of politicians. And Starmer is being selected against and Johnson for ��� at least for now.

You might think that my depiction of success as owing more to luck than skill is a leftist mindset. But the left has a long (and I think ignoble and ineffective) habit of ignoring this principle and instead looking for heroes ��� from Napoleon through Ho Chi Minh and Che Guevara to Hugo Chavez. But there are no heroes, and even if there were we would lack the talent to find them.

May 16, 2021

Markets & the right

Samuel Gregg reminds us of an important fact about rightist thinking ��� that the right has always been ambivalent about markets.

This is as true in the UK as in the US. We saw this, for example, in the 19th century when the Tories split up over the abolition of the corn laws and when Thomas Carlyle damned economics as the ���dismal science��� for wanting to abolish slavery. We saw it too in Roger Scruton���s mixed feelings about Thatcher:

She leaned too readily on market economics, and ignored the deeper roots of conservatism in the theory and practice of civil society.

And we see it today in the Tories imposing trade barriers not just between the UK and EU but even within the UK. Perhaps the most spectacular example of this is John Redwood���s seamless move from ardent Thatcherite to supporter of autarky.

All this poses the question, though: why is it now that the right is moving away from free market thinking rather than twenty or thirty years ago?

The answer, I suspect, lies in part in the one thing that conservative thinking has always been consistent about ��� its concern to protect private sector hierarchies. As Corey Robin says:

The priority of conservative political argument has been the maintenance of private regimes of power.

And here���s the thing. Free markets sometimes help maintain these regimes but sometimes threaten them. In the 80s and 90s, markets helped to entrench capitalist power, because deindustrialization and globalization helped to weaken the power of organized labour. (This isn���t to say that the decline of unions was purely due to market forces: the coppers at Orgreave were agents of the state.) In these circumstances, the right discovers a love of markets.

At other times, though, markets disrupt hierarchies. The free trade espoused by Smith and Ricardo was bad for landlords: Smith was, in his day, a heterodox economist.

What we���re seeing today is a reversion to those times. Markets now are a danger to the existing order, in three different senses.

First, some employers are befuddled by the unusual sight of localized labour shortages. Obviously, Econ101 says the answer to this is to raise wages ��� which some are loath to do. The notion that market forces might actually work to workers��� advantage rather than capitalists��� is an unfamiliar and disturbing one.

Secondly, in a free market employers can hire whom they want ��� which means immigration. A market society is a cosmopolitan society. Rightists who feel awkward about hearing foreign languages don���t want that*.

And thirdly British capitalism is now to a large extent a rentier economy, as Brett Christophers has shown. A genuinely free market, however, would undermine this. Freer copyright laws would curb intellectual property rents; ending banks��� implicit subsidy and encouraging competition would cut financiers��� rents (pdf); more competitive government tendering could reduce what Christophers calls contract and infrastructure rents; and shifting taxes from income to land value would end landlords��� power to expropriate for themselves the positive externality of improvements to local areas. In ways such as these, introducing more market forces would undermine actually-existing capitalism.

It���s no accident, therefore, that the right should now be falling out of love with free markets ��� because these are no longer a way of preserving the existing order. You cannot tell intellectual history purely through the lens of ideas. Material interests matter, and it is these that are turning the right away from markets.

If this sounds conspiratorial, it shouldn���t. Think of politics as being a little like natural selection. Policies and ideas arise if not as random mutations then at least sometimes wholly or partly independently of material interests. But the environment then selects which ones survive or thrive ��� and a key part of the environment is class interests. The Tories good fortune has been to find a way which reconciles voters��� longstanding hostility to free markets with both their own interests, their love of order and inequality and electoral success.

My story here is not just about the right, however. There���s a message for technocrats. They tend to see markets as a mere engineering problem: sometimes they work well and sometimes they need fixing. Maybe this would be true in an ideal society. But we don���t live in such a society. Instead, we have a class-divided one in which capitalists and rentiers have the whip hand ��� and that hand determines when and how markets get to work.

And there are points here for the left. The powerful sections of the right are no longer free marketeers. Pretending that they are is a tactical error, which fails to see that one of the Tories��� great strengths is its ability to change. Also, if markets can be a threat to actually-existing capitalism, perhaps many leftists should rethink their instinctive antipathy to them.

* No. Immigration does not reduce natives' wages (except very slightly for a minority).

May 11, 2021

Class

There���s much talk, some sensible and some less so, that the Labour party has lost touch with the working class. Khalid Mahmood for example complains that the party is ���doing better among rich urban liberals and young university graduates than it is amongst the most important part of its traditional electoral coalition, the working-class.���

Of course, you can use words to mean whatever you want them to, but to those of us in the Marxian tradition, such a complaint makes no sense because of how we define ���working class���.

For us, being working class is not about your lifestyle or background but about economic relationships. If you don���t own (significant) means of production and must sell your labour-power, you are working class. By this definition, young graduates and people drinking fancy coffees in That London are just as working class as an older manual worker in Hartlepool. Ponces are just as working class as racists.

Nor is class simply a matter of income. An employee on a high wage is working class whereas a self-employed person on a lower income is not: s/he is a petty bourgeois in Marx���s words.

Being a worker matters in capitalism because it is a source of unfreedom and alienation. The unfreedom might be merely (!) a matter of having to spend time doing something you���d rather not, or it could mean suffering tyranny and degradation. The alienation comes from the fact that our work is a way not of realizing our nature but rather is foreign to us.

On both counts, graduate jobs can be as bad as manual labour. One feature of recent years has been that professional jobs have seen more onerous hours, less autonomy and more precarity - which is one reason why such workers have become less likely to vote Tory . And bullshit jobs are experienced as pointless and alienating whilst some manual work can be a source of pride.

And on both counts, we can't really speak of retired people as working class. If they don't need to work (and increasing numbers of over-65s in recent years have had to) they are free from the unfreedom and alienation that is the plight of the working class.

Of course, members of the working class differ in their individual bargaining power and many can use this power to claim a share of profits. This does not alter the fact that they are working class: their share of the pie is conditional upon them selling their labour-power*.

From this perspective, the working class comprises much more than older, white less educated people. Migrants, ethnic minorities and LGBTQIA people are just as working class too. What matters is whether one must sell one���s labour power. This simple fact unites people with otherwise very different experiences and viewpoints.

There working class have never been an homogenous mass. Labour���s old Clause IV, written in 1917 by the Fabians Sidney and Beatrice Webb, spoke of ���workers by hand or by brain��� precisely because it saw a commonality between manual and non-manual work. That was right, just as today the working class can be in the material or immaterial economy.

Of course, Marxists have always known that class in this objective sense differs from how people feel. As Erik Olin Wright said, "it���s never been true that class, by itself, explains consciousness". It often takes redundancy or a bad boss for people to learn what class they are in. Ash Sarkar is right:

How people perceive their own class has little to do with the economic base. As the oft-quoted Stuart Hall once said, ���politics does not reflect majorities, it constructs them.���

You might object that by this definition almost everybody is working class.

This isn���t quite true: I���m not as I can afford to live off my capital and am working only to retain optionality. Insofar as it is, however, this a feature not a bug.

For one thing, it vindicates Marx���s prediction that the working class would grow:

The lower strata of the middle class ��� the small tradespeople, shopkeepers, and retired tradesmen generally, the handicraftsmen and peasants ��� all these sink gradually into the proletariat���Thus the proletariat is recruited from all classes of the population.

And for another thing, the fact that so many people are working class means that class politics can be a source of unity and solidarity. As Janan Ganesh ��� no Marxist he ��� has written, the class divide:

feels less fraught than the rifts over race, gender and sexuality that make up what we know, for want of a better euphemism, as identity politics. It is a matter of numbers. A crude campaign against the one per cent would put, at least in theory, all other Americans on the same side.

Which brings us to the point. There are powerful reasons why the right and their quislings want to deny this perspective on class. They want to distract us from the fact that the economy and society is structured around ownership and that what you own determines what power you have. They also want to divide and rule. The more people are divided between towns and cities, graduates and non-graduates, leavers and remainers, black and white, trans and cis, and so on and on and on, the less likely they are to realize how much they have in common.

Of course, bourgeois politics has always been pulling these tricks, and one way of doing so has been to pretend that class is just another lifestyle rather than a manifestation of economic structure. What is remarkable is that such tricks are as successful today as they always have been.

* A more awkward type for Marxists is what Wright (whose work I commend) called ���contradictory class locations (pdf).��� Bosses and investment bankers, for example, are working class in the sense that they sell their labour, but are capitalist in that they get a chunk of the proceeds of others��� labour and so are exploiters. I���m not sure how this invalidates the Marxian scheme though: a taxonomy can be useful even if some people are members of more than one set.

May 8, 2021

On centrist vacuousness

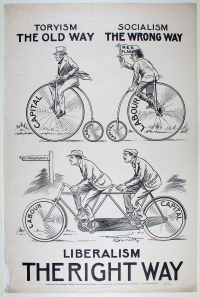

What would you think of a political party that promised to: cut unemployment by one million over two years; increase public investment; borrow more to finance extra welfare benefits and NHS staffing; increase foreign aid; promote worker coops; and aim for ���a major extension of profit sharing and worker share-ownership to give people a real stake where they work���?

It���s pure Corbynism isn���t it?

Well, no. All these were in the 1983 Liberal-SDP manifesto. Back then, they were centrist policies.

Not that this was unusual. In 1924 ��� the year of picture opposite ��� Liberals called not just for workers to get a share of profits but also for the compulsory purchase of land for housing development and came close to advocating a land value tax.

By contrast, today���s centrists show no such enthusiasm for empowering workers. The LibDems had five years in government without expanding worker coops an inch. Change UK (remember them) were silent on them. And the Labour right are hardly deafening us with their calls for greater worker democracy.

I suspect there���s a simple explanation for this. Centrism is intellectually parasitic, preferring triangulation to developing its own ideas. Its support for coops and profit-sharing was a way of splitting the difference between the right���s belief in private ownership and the left���s in more full-blooded public ownership, and a way of trying to pacify a militant labour force. With workers having been defeated in recent years, however, centrists see no need for such pacification. Indeed, they don���t even need to use the language of ���capital��� and ���labour��� as they did in the 1920s. Instead, they���ve retreated into the comfort zone of acquiescence to capital ��� as demonstrated by the post-Westminster careers of Nick Clegg and the Cukkers.

This explains something else ��� centrists��� lack of interest in economic policy, or indeed policy generally. It���s clear what they don���t want ��� the sort of Corbynite policies centrists advocated in the early 80s. But it���s much less obvious what their positive agenda is. What, for example, are their answers to the problems of inequality, stagnant productivity and real wages, unaffordable housing and so on?

We heard this vacuousness from Peter Mandelson on the Today programme yesterday (2���19��� in). Nick Robinson asked him what changes he���d like to see Labour make. ���I���ll come to that��� replied. But he didn���t.

Even when they have deigned to write down some ideas, political centrists have ignored such issues. Pretty much the only reference to economic policy in Change UK���s launch manifesto was to the need for the government���s ���responsibility to ensure the sound stewardship of taxpayer���s money���, as if we were still in a world of bond vigilantes. And Chris Leslie���s Centre Ground paper (pdf) made almost no reference to the fact that the financial crisis and subsequent stagnation in real wages and productivity requires centrists to re-assess the economic idea they had in the 90s.

Instead of intellectual analysis, centrists offer us two things. One is pure retail politics, accommodating itself to a selective perception of what voters want: Mandelson ��� once a Remainer ��� for example now thinks Labour must embrace ���Brexit values��� without also noting that higher taxes on the rich and more nationalization are also popular. Among its many flaws ��� among which is that this would alienate lots of Labour voters - this ignores the fact that public opinion is changeable: Brexit, for example, moved from being the obsession of a few cranks to the dominant issue in politics as a result of right-wing campaigning and economic stagnation. Taken opinion as given thus means skating to where the puck is rather than to where it is going.

A second strand of centrism is more common among media centrists. Take for example Jonathan Freedland���s anger at Johnson���s corruption. When given the choice between Johnson and the alternative centrists like Freedland ducked out, failing to appreciate that real life is sometimes a choice of the lesser of two evils. In this sense, centrism is a form of identity politics ��� an urge for what Richard Sennett called a purified identity which leads to a whine about ���why can���t you all be sane, rational and honest like ME?���

Now, in saying this I���m not damning all centrists. If we look outside the political-media circle we can find signs of intelligent life such as in Radix or in Sam Bowman and Stian Westlake���s work. Much of this, however, underplays the class problem ��� of how to build support for policies such as land taxes or tougher competition policy in the face of hostility from rentiers.

That���s a separate argument, though. The fact is that even where centrists do have good ideas these have not (yet?) found their way into the political centre.

Hence Labour���s problem right now. Whilst people will vote for something, even if it���s lousy, they don���t often vote for nothing. The vacuity of the centre has left Labour with a clapped out leadership bereft of ideas without a vision or a coherent message. As Grace says: ���Labour has a choice to make: socialism or Pasokification.���

Of course, it has not always been this way. It���s easy to forget that New Labour actually had an intelligent and coherent ��� if flawed ��� economic narrative. The challenge for the Labour right is to either discover a version of that narrative fit for the 2020s, or to remain the braindead quislings of rentier capital.

April 29, 2021

Capital's political power

The Tories are corrupt. That���s the message of handing out PPE contracts to government cronies; Cameron���s lobbying for Greensill; the murky financing of Johnson���s home ���improvements���; and Robert Jenrick���s doing the bidding of Tory donors. All this, says Grace Blakeley, highlights the problem of ���politicians and business people being in each others��� pockets.���

All this, however, is only part of the story. Even if our politicians were honest and even if the media were unbiased capitalists would still have disproportionate (pdf) power over government. Grace is right to say that ���our ���democracy��� works for the powerful, not the people.��� But this is due not to the shortcomings of particular individuals, but to systemic forces.

One of these was pointed out by that great left-wing economist Adam Smith. We have, he wrote, a ���disposition to admire, and almost to worship, the rich and the powerful, and to despise, or, at least, to neglect persons of poor and mean condition���:

We frequently see the respectful attentions of the world more strongly directed towards the rich and the great, than towards the wise and the virtuous. We see frequently the vices and follies of the powerful much less despised than the poverty and weakness of the innocent���The great mob of mankind are the admirers and worshippers, and, what may seem more extraordinary, most frequently the disinterested admirers and worshippers, of wealth and greatness.

Gordon Brown ��� a more honest man than his successors ��� was prone to this. He praised top bosses as ���wealth creators��� and courageous leaders, inviting several to become ministers or advisors, such as Mervyn Davies, James Crosby, Shriti Vadera and David Freud.

The financial crisis and decade-plus long stagnation in productivity have of course shown that bosses in aggregate do not have the especial expertise Brown imputed to them. But the deference continues. If you listen to pretty much any 7.20 interview on Radio 4���s Today programme you hear bosses being interviewed as if they were impartial (even heroic) experts, whereas trades unions are portrayed as sectional interests.

It���s not just politicians and journalists who are deferential, though. So too are voters. How else to explain their belief that the Tories are economically competent when the truth is that they are criminally stupid?

Such deference amplifies a separate lever that capitalists have ��� business confidence. This, it is believed, is essential for investment and job creation. And so, wrote Michal Kalecki, ���everything which may shake the state of confidence must be carefully avoided because it would cause an economic crisis.��� Hence the success of demands for low corporate and top tax rates.

There���s a third lever ��� ideology. John Jost has written of system justification theory (pdf), which he defines as the ���process by which existing social arrangements are legitimized, even at the expense of personal and group interest.��� This works through many mechanisms. There���s a form of anchoring (pdf) effect: Kris-Stella Trump shows how our perceptions of what���s fair are heavily influenced by the existing distribution of income. There are reference group effects: we compare ourselves to those around us, so many low-wage workers resent benefit claimants more than rich bosses. Then there are status quo biases and the just world illusion ��� mechanisms whereby we tolerate or even deny existing injustices.

Related to this is an asymmetric noise effect. As Amartya Sen pointed out, the very worst off are often ���more easily reconciled to deprivations than others reared in more fortunate and affluent circumstances��� (Ethics and Economics, p45). And so they make less noise than the wealthy, even if the latter���s complaints are trivial or arise from narcissistic over-entitlement.

I���ve no doubt that our media magnify these ideological biases towards capital. But I���m not sure they create them. One reason I say this is that we see the same cognitive biases that dispose voters to accept inequality in other domains such as the stock market. For example, analysts��� forecasts for a firms��� earnings growth are wrongly anchored (pdf) by the industry average growth, and the same reference group effect that causes people to punch down or across rather than up might help explain where there is often no risk-reward trade-off in finance. It has long puzzled me that when I write about cognitive biases in stock markets I���m seen as an intelligent technocrat but when I discuss the same ones in politics I become a loony Marxist drivelling about false consciousness.

None of this is to say that it is always a terrible thing that capital has undue sway over politics: sometimes the interests of capital and labour coincide. Our problem is that, in recent years, it has been the most backward segments of capital that has had most influence ��� rentiers rather than genuine entrepreneurs.

My point, though, is that the political power of capital over governments is not merely the result of cronyism and corruption. It is not therefore something to be cured simply by electing decent, honest people ��� although this job seems too much for the British electorate. If we are to have genuine democracy ��� in the sense of equality of political power ��� we need structural change.

April 25, 2021

On selection mechanisms

Market research is vital. Had the breakaway six done some, they���d have known it was an unpopular idea and so wouldn���t have destroyed their bargaining power with UEFA and their (in some cases tiny anyway) popularity with fans.

Market research is a menace. Sir Keir Starmer���s concern with focus groups is creating timidity and a lack of direction. It���s causing him to reject Wayne Gretzky���s advice to skate to where the puck is going to be rather than to where it has been. Henry Ford never actually said ���if I had asked people what they wanted, they would have said faster horses.��� But it captures a limitation to how much we should listen to market research.

Which of these paragraphs is correct?

Both. What we have here is an example of Niels Bohr���s saying: the opposite of a great truth is another great truth.

We should think of all decision-making systems ��� be they corporate management, research methods, government regulation, our own mental habits and so on - as selection mechanisms.

Sometimes, such as in politics, these selection mechanisms select the worst, leading to inadequate politicians and bad ideas. Other mechanisms, though, can select against the worst whilst not necessarily selecting the best. I suspect this is true of market research. It���s perfectly possible that market research would have told the breakaway six they were backing a turkey whilst at the same time not telling Labour what will win most votes: one reason for this could be that people don���t actually know their preferences, and certainly not their future ones.

If this is the case (and this post is not really about that) then what we have here is one of a set of decision-making systems which function better at weeding out egregiously bad results than they do as selecting for the best ones.

Perhaps the best-known example of this is the US constitution. Its function is more to protect against tyranny than it is to ensure the best possible government, which might on occasion require a more activist state than the constitution permits.

Another example is Friedman���s idea (pdf) of monetary policy. The best it can do, he thought, is to ���prevent money itself from being a major source of economic disturbance.��� It cannot itself achieve really good things such as lasting full employment or rapid growth. That requires the working of ���those basic forces of enterprise, ingenuity, invention, hard work, and thrift���. Friedman, I think, was too optimistic about the extent to which monetary policy would facilitate the latter. But the point is that, for him, good monetary policy was mostly ���a negative proposition: avoid major mistakes��� ��� advice which, admittedly, his epigones did not wholly follow.

Yet another example comes from my day job. There���s a lot stock-pickers can do to reduce the chance of bad outcomes such as avoiding the recency bias and disposition effects, knowing the edge of one���s competence, or not trading too much. These rules reduce the chance of us losing a lot. But they don���t much help in picking the best stocks ��� not least because, as Hendrik Bessembinder has pointed out, these are only a tiny fraction of all the stocks on the market.

A further example is medical regulation. Demanding that drugs meet stringent safety standards before coming to market can prevent catastrophes. But this comes at the expense of delaying the roll-out of a vaccine that would allow life to return to normal. In this case, procedures that select against bad outcomes can also impede good ones.

In his new book, Economics in One Virus, Ryan Bourne claims this is true generally. Regulations, he says, ���restrict businesses and individuals��� adaptability to new conditions ��� they curb within-market innovation.���

Selecting against bad outcomes, then, is different from selecting for good ones. And indeed, doing the one can sometimes actually impede the other. Neoliberal management of universities, for example, has probably done a good job of selecting against academics who are idle drunks, but given the replication crisis ��� incentivized by the pressure to publish ��� it���s done less well at selecting for good work.

Which selection mechanism we should adopt depends upon context: what would have worked for the breakaway six (arguably) doesn���t work for Starmer. As Edmund Burke said: ���The circumstances are what render every civil and political scheme beneficial or noxious to mankind.��� If you���re running a nuclear power station your focus should be upon avoiding worst-case outcomes, whereas in creative industries mechanisms should instead select more for best-case ones: this entails trade-offs because, as Dan Ariely has shown (pdf), dishonesty and creativity are often two sides of the same coin.

My point here is simple. We must ask of any decision-making system ��� that is to say, any power structure ��� what does it select for, and what does it select against? Yes, this is true of government regulation, but it is equally true of corporate management and political processes.

April 19, 2021

Capitalists against competition

Capitalists hate competition. That���s the message of plans by several big clubs ��� as well as Sp*rs ��� to form a ���super��� league in which they���ll be protected from the danger of relegation or from competition from emerging teams.

The smarter capitalists have of course long known that profits come from avoiding competition. Warren Buffett advises shareholders to look for companies with ���economic moats��� ��� things that protect them from competition. And Peter Thiel says start-ups should aim to become monopolies. ���Competition is for losers��� he says.

But here���s the thing. Striving for monopoly is by no means always a bad thing. The pursuit of brand power ��� one of Buffett���s moats ��� causes firms to try to make high-quality products consumers can trust. The urge for more market share causes them to undercut rivals and so keep prices low. Or the desire to win the natural monopoly that comes from having a dominant platform business leads firms such as Facebook or Twitter to give away services.

In ways such as these, capitalists��� attempts to overcome competition can work for everyone���s benefit.

But, but, but. This is only part of the story. Proposals for a breakaway league remind us that there are more malevolent ways of seeking to over-ride competition. Adam Smith famously saw one of these:

People of the same trade seldom meet together, even for merriment and diversion, but the conversation ends in a conspiracy against the public, or in some contrivance to raise prices.

We can add to this the pursuit of restrictive patents and copyrights; driving down of wages and working conditions; or lobbying governments for special favours.

Which poses the question: what can be done to ensure that capitalists strive for monopoly in benign rather than malign ways.

Changing ownership is not always the answer. Yes, there���s a case (pdf) for football clubs to be run by fans. But accountancy firms have long been worker-owned, and few people pretend that business is a model of a well-functioning market. This isn���t to say there���s no case for worker ownership ��� there definitely is. It���s just that coops��� many merits do not include being a magic bullet for producing the right kind of competition.

Nor, I suspect, are laws and regulations. Technocrats often forget that the law is endogenous. It is not imposed from outside by benign philosopher-kings, but is instead prone to being captured by capitalists. As Pablo Torija Jimenez has shown, the state serves the interests of the rich.

A third possibility ��� proposed for example by Jesse Norman in his book, Adam Smith: What He Thought and Why it Matters ��� is for capitalists to have the right kind of social norms, a sense of fair play. But of course, if they ever had such norms, they no longer do so.

Which leaves one other option ��� countervailing power. Strong trades unions in the post-war period, for example, not only prevented wages (of white men at least) being egregiously cut but also limited bosses��� rent-seeking.

If we are lucky, such countervailing power will kill the European super league. If enough players and managers resist it, along with fans, then club owners might cave in.

I���m reminded here of something Luigi Zingales has said. He points to what happened in 1994 when shareholders tried to stop Maurice Saatchi giving himself a lot of share options. He flounced off, taking with him clients and colleagues. The lesson of this, said Zingales, is that formal ownership is not the same as control. In the same way, Fenway Sports Group might formally own Liverpool FC but if Jurgen Klopp and some players were to oppose a super league, could they really force the club into it?

There���s no point making a firm prediction here: we���ll find out soon enough.

Instead, the point is that capitalists��� hatred of competition sometimes works for the public good and sometimes not. Which it is ��� and whether non-capitalistic forms of ownership can do better ��� depends upon context and environment which differ from industry to industry, place to place and time to time. It does seem, though, that recent years have seen these contexts change for the worst.

April 16, 2021

On generational difference

There���s been a little pushback to this claim by Ezra Klein, but I suspect there���s a lot in it:

I���ve been struck by the generational divide within the Democratic Party. Washington is run by 20- and 30-somethings who run the numbers, draft the bills, brief the principals. And there is a marked difference between the staffers and even the politicians whose formative years were defined by stagflation, the rise of Reaganism and the relief of the Clinton boom, and those who came of age during financial crises, skyrocketing personal debt, racial reckonings and the climate emergency. There are exceptions to every rule, of course ��� see Sanders, Bernie ��� but in general, the younger generation has sharply different views on the role of government, the worth of markets and the risks worth taking seriously.

We have lots of evidence that our formative years can shape our perceptions many years later. For example, Ulrike Malmendier has shown that people who experienced recession in their youth own fewer (pdf) equities than others even in old age; that CEOs who saw the Great Depression run their companies more conservatively (pdf) than others; and that FOMC members (pdf) who saw higher inflation when young and impressionable are more likely to be hawks. And Erin McGuire writes:

Individuals who begin their lives by observing an economic downturn remain pessimistic and risk averse with respect to investments over the course of their lifetimes.

Napoleon, then, was correct: ���to understand the man you have to know what was happening in the world when he was twenty.���

This, I suspect, bears upon the debate about how big a threat is inflation. Oldsters (like Larry Summers?) whose formative years saw high inflation are more worried about it now than are the (western) under-40s who have never experienced it.

This is consistent with David Hume���s thinking. What we see when we are in our teens and early 20s are impressions, things which enter our mind with ���most force and violence.��� What happened before then is what we read about in books, and what happens after are events which have less impact on our crusty minds. They are ideas, which are mere ���faint images���.

Now, put yourself in the shoes of someone who is, say, 30. The financial crisis happened when you were in your late teens, and your subsequent years have seen stagnant real wages, unaffordable housing and high student debt. The impression you get is that capitalism doesn���t work. Of course, some older folk will tell you that there was a time when capitalism was functional, but for you this is a mere idea, a faint image.

By contrast, someone in their late 40s might well have had the collapse of communism make a forceful impression on them, whilst they saw affordable housing and years of economic stability. They have a much more favourable impression of capitalism therefore.

But of course, not all of us wrinklies have such an impression. My formative years were ones of violent class struggle, industrial decline and the deep recession and mass unemployment of the early 80s. Hence my sympathies with the likes of Grace Blakeley and Aaron Bastani.

Many of my contemporaries as teenagers had experiences like this:

Father (who left school during the full employment of the late 50s): Get off the settee and get a job.

Son: There aren���t any jobs.

Father: There are if you look.

Much effing and jeffing by both parties. Son slams door and walks out ��� to visit his grandad who, having grown up in the 1930s, knows his predicament.

Of course, not all 50-somethings share the formative experiences of my youth. David Cameron and Boris Johnson are around my age. But the 1980 recession looked very different from Eton than it did from a single-parent terraced house in inner-city Leicester. Napoleon���s point still holds. Class matters, as well as age.

We could extend the point. One reason for the generational divide over Brexit is that older folk who came to maturity before we joined the EU have the impression that we can do well outside the EU, whilst younger folk who have known nothing but EU membership see no reason to rock the boat.

All of this (as you'd expect) is to echo Marx:

The mode of production of material life conditions the general process of social, political and intellectual life. It is not the consciousness of men that determines their existence, but their social existence that determines their consciousness

The conditioning, however, is not simply mechanistic: it���s not that this year���s economic circumstances alone influence our thinking, but rather that those of our formative years do so.

This helps explain why some bad ideas ��� such as a belief in fiscal rectitude ��� linger on after their material justification has vanished. We do not sufficiently update the thoughts acquired in our formative years, but rather are Bayesian conservatives who cleave to our priors. OK, boomer?

Chris Dillow's Blog

- Chris Dillow's profile

- 2 followers