Chris Dillow's Blog, page 10

November 18, 2021

Frames, stories and political change

Sometimes, opinions change a lot even though the facts change only a little. So it seems to be with the case of MPs second jobs. Everybody knew for years that many MPs had them but most regarded it as acceptable. Until, suddenly, it is sleaze.

What���s happening here is not so unusual. We often see it in financial markets. In the mid-90s, for example, several Asian countries ran large external deficits. And for a long time, these were seen as healthy because fast-growing countries should suck in foreign investment ��� until, suddenly, they weren���t and we had a financial crisis. As Sushil Wadwani, a former MPC member said (pdf):

Countries with a current account deficit can have a currency that stays strong for a surprisingly long period, until, sometimes, there is an abrupt adjustment.

Similarly, in the late 90s high prices of tech stocks were seen as justified by the prospect of a new economy ��� until they suddenly were not. And the US housing market started to cool off in 2006, but for months nobody thought this was a problem ��� until suddenly it was.

A similar thing might be happening to Boris Johnson. Everybody has known for ages that he is a lightweight comic charlatan. He has not changed, nor done anything surprising. It���s just that the same person is now provoking different feelings amongst his erstwhile supporters.

To understand what���s going on here, we must remember that we rarely see things in isolation as bald facts. Instead, we select and interpret them. As MLJ Abercrombie wrote:

The information that a person gets���depends on the context, or total situation, and on his past experience, which is usefully thought of as being organized into schemata. Human relations play an important role in perception both in that they are often a significant part of the context, and in that they have contributed to the formation, testing and modifying of schemata (The Anatomy of Judgment, p18)

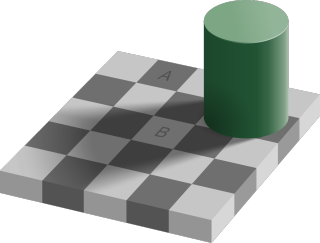

This is why we are so prone to mis-readings, typos and optical illusions: squares A and B in my picture are in fact the same shade.

Facts, then, come within frames (pdf). And as Daniel Kahneman wrote in Thinking Fast and Slow, ���different ways of presenting the same information often evoke different emotions.��� He gives the example of how even trained doctors react differently to the statement ���the odds of survival are 90%��� than to ���the mortality rate is 10%��� even though they are different frames of the same facts. And, he adds, ���your moral feelings are attached to frames, to descriptions of reality rather than to reality itself.���

Even irrelevant changes ��� from a 90% survival rate to a 10% mortality rate ��� can elicit big changes in emotions. And if irrelevant changes can do so, so too can small ones. Owen Paterson���s corruption, for example, might not be much different from that of other MPs in the past. But it has changed the frame. In the same way, small changes have tipped investors from not worrying about current account imbalances, valuations or housing markets to panicking about them.

But there���s more. Frames are created by stories. And as Robert Shiller shows (pdf) in Narrative Economics, these are like viruses: some just die whilst others spread rapidly. And as they spread, so they change the frames in which we see things. Sir Keir Starmer is trying to achieve just such a change when he says of Johnson that ���the joke isn���t funny any more.���

What I���m describing here is similar to but different from Timur Kuran���s account of preference falsification. He shows how oppressive regimes can survive for years because everybody believes that everybody else supports the regime and so keeps quiet. But when, suddenly, people realize their error they rise up and topple the government. In this way tyrants such as Harvey Weinstein or Nicolae Ceausescu saw their power disappear overnight.

My account differs from his because people aren���t misrepresenting their opinions. Sure, they are going along with the crowd ��� peer pressure being so powerful as Robert Frank has shown ��� but their expressed opinions are what they genuinely believe.

But it has something in common with it too. What we have in both cases is something described by Didier Sornette and Peter Cauwels; that social structures can seem stable only to suddenly change a lot.

And we cannot predict when or if this will happen or what will cause it; the triggers often seem innocuous. Which vindicates Jon Elster���s crucial observation ��� that we can sometimes explain without being able to predict. All of which means we must be much more humble about our ability to foresee political change.

November 14, 2021

The decline of economics

Edward Luce writes:

Bill Clinton���s 1992 campaign watch phrase was ���it���s the economy, stupid���. Today it would be ���it���s the culture, idiot���.

He���s right, but this poses the question: why did this change? The question of, course, applies to the UK as well as the US.

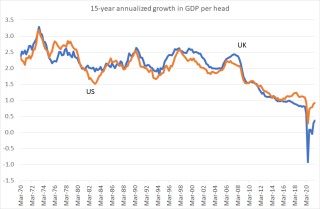

One fact deepens the puzzle. It���s that trend growth in GDP per capita has halved since the 90s*. This should have made economic issues more important, because it���s much less obvious now that the economy can thrive without policy intervention. Back in the 90s, politicians might reasonably have thought ���the economy will take care of itself as long as we don���t do anything too stupid, so let���s focus on other matters.��� Today, we cannot take growth for granted.

But in fact, the opposite has occurred. As economic performance has worsened, so the salience of economics in politics has declined ��� so much so that, as Stian Westlake has said, the Tories ���seem to have stopped talking and thinking about economics.���

I stress that word salience. There have always been clashes between cultural liberals and conservatives. For decades, however, these were generally secondary to economic debates. Today they are not.

So what changed?

The cause of the increased salience of the culture wars should by now be well-known. Events have vindicated the point Ben Friedman made in 2006 ��� that slower economic growth promotes illiberalism and reaction, which triggers hostility from social liberals and egalitarians.

But why has the salience of economics declined?

I don���t think it���s because politicians have accepted the advice of Dietz Vollrath or John Landon-Lane and Peter Robertson, that national policies can do little to raise long-term growth** - any more than they have heeded green calls for degrowth.

Instead, one possibility is that people just don���t want economic growth. Philip Hammond (remember him?) once said that people ���did not vote to become poorer���. But they did ��� in 2010, 2015, 2016, 2017 and 2019. This might not be a case of adaptive preferences, of people resigning themselves to not wanting what they can���t have. An ageing population means there���s a big constituency of retired or nearly-retired people who have little direct interest in increased prosperity. And the Easterlin paradox tells us that economic growth doesn���t make us much happier anyway. One reason for this is that it is a process of creative destruction ��� but this brings with it uncertainty and the disruption of jobs and communities. Why want that?

There���s another way in which economic growth is undesirable. Measures to increase it would almost certainly hurt powerful vested interests. Centrist policies to improve productivity would include toughening up competition policy and shifting the tax burden from incomes to land. And that���s not to mention more radical options such as increasing worker democracy or reducing inequality. Also, faster economic growth would lead to higher real interest rates, which could reduce asset prices and deter the leverage on which the ���picking up pennies��� strategies of investment banks and private equity depend. There���s a powerful coalition for whom all this is a nasty prospect.

You don���t have to be a Marxist to believe that we���ve reached a point where the relations of production have become a fetter upon the productive forces. Joel Mokyr has written:

Every society, when left on its own, will be technologically creative for only short periods. Sooner or later the forces of conservatism���take over and manage through a variety of legal and institutional channels to slow down and if possible stop technological creativity altogether.

To those of us formed in the 70s and 80s, all this seems weird. We were brought up to see Thatcherite Toryism as an economic project ��� albeit one with the aim of achieving cultural change. So isn���t the lack of interest in economics yet another way in which the Tories have become anti-Thatcherite?

Perhaps not. Maybe Tories were not really interested in economics at all, but something else.

Their concern about the UK���s relative economic decline in the 70s might have been motivated less by a desire to raise living standards and more because they feared the UK���s loss of power and prestige on the global stage. In this context, it was the Falklands war more than economic policy than transformed self-perceptions of the UK, just as Brexit now bolsters the self-image of the UK as a strong independent ���nation���.

And perhaps Thatcher���s assertion of ���managers��� right to manage��� was not a means of increasing efficiency but rather a desire to impose traditional hierarchies. The crisis of the 70s was not so much an economic crisis ��� real GDP then grew better than they have in recent years ��� as a political one. Workers were getting uppity, and Tories hated that.

Maybe, therefore, the rise and decline of the salience of economics within the Tory party (and the media) isn���t so strange after all. Economics was only a tool for achieving a sense of national pride and preserving inequality, and the tool could be safely returned to the shed when the job was done.

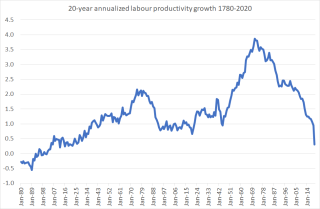

* This isn't simply the result of the financial crisis. My chart shows that rend growth was declining before then. And anyway, the crisis was endogenous.

* Note the strong correlation in my chart between UK and US growth. It is consistent with Landon-Lane and Robertson���s point that medium-term growth is the result of mainly supra-national factors.

November 8, 2021

Working less

Many people believe we need to work less if we are to avoid catastrophic climate change. We must ���dramatically reduce economic activity��� says George Monbiot. ���We should cut working hours to save the planet��� agrees Simon Kuper.

In truth, though, there are other reasons to work less, as Martin Hagglund argued in his brilliant This Life. Our most fundamental possession, he says, is time, and we can only be truly free if we can choose what to do with this scarce asset. For many of us, though, having to work long hours or for many years deprives us of this freedom.

Which runs into the objection that working significantly less would be bad for the economy.

Hagglund���s solution to this is ingenious. What we need, he says, is a ���revaluation of value���. We must judge economic success not by how much we produce, but rather by how much free time we have:

To be wealthy is to be able to engage the question of what to do on Monday morning, rather than being forced to go to work in order to survive.

He believes such wealth ��� such freedom ��� is impossible under capitalism. Yes, capitalism tries to economise on labour. But it does do erratically and inequitably, by creating unemployment (with the misery it causes) alongside others who work too much.

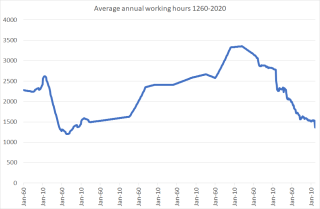

History suggests he has a point. Working hours increased markedly during the industrial revolution, as E.P. Thompson described (pdf). And whilst they���ve fallen since the late 19th century, the average working week is longer now than it was in the 15th century. (I'm using Bank of England data here.) What���s more, the pace of decline in working hours seems to have slowed. In the 30 years to 2019 they dropped less than 6%, compared to an 18% fall in the 1959-89 period: this fact might be connected to the weakening of trades unions in this time.

Of course, working hours are but one measure. By another, free time has increased hugely since the early 20th century because many of us are enjoying long retirements now. But progress here has stalled. The state pension age has risen, and young people ��� unable to save because of high rents - expect to work until they drop.

Which suggests Hagglund is right to say we need some radical economic changes if we are to increase free time.

Two other facts suggest as much.

One is that the smaller is the economy, the larger will be the share of government spending therein. If the economy shrinks spending on health and social care will not, so these will take up a bigger share of activity. Jason Hickel says that degrowth is compatible with increasing ���people���s access to the resources they need to live long, healthy, flourishing lives.��� But that means a big increase in the share of social spending in economic activity. Degrowth ��� for environmental or Hagglundian reasons ��� requires decommodification*.

The other is that whilst we wealthy people could easily work less and consume less, those who are working long hours just to get by cannot. One solution to this would be a cultural revalorization of work, to recognize the low-paid as being the skilled workers they in fact often are. But another would be greater redistribution, as Monbiot acknowledges.

In fact, we���ll need redistribution in another sense ��� from landlords to tenants. Hagglund���s democratic socialism would reduce capitalist exploitation, the fact that we work longer than necessary for the benefit of capitalists. But if we are to work less we also need to reduce rentier exploitation, the fact that we work longer than necessary to pay landlords. Otherwise, working less would mean handing over an even bigger share of one���s wages to landlords.

The inference is clear: cutting working hours and output cannot be an isolated change. It requires other big cultural and economic changes.

Which runs into a problem: how would such changes affect productivity?

You might think this irrelevant for green degrowthers. I���m not sure. Even if we are shrinking GDP we need to improve energy efficiency. And Hagglund���s vision of more time increasing our freedom requires that productivity be high. The sooner we can get our work done the sooner we can knock off, and some of us will want to spend our freer time on some activities that consume resources.

But raising productivity is a massive task even in the best of times. It requires that we overcome not just vested interests but also Baumol���s law (it���s hard to raise productivity in many services), diminishing returns, and a lack of big innovations. Indeed, it might be that it���s impossible to do so, as productivity is determined by global factors rather than those under the influence of national governments.

And shrinking output and working hours would add to these obstacles.

For one thing, it would put us on the wrong side of Verdoorn���s law, the correlation between aggregate demand growth and productivity growth. If companies are to invest in energy or labour-saving technologies they need confidence that future demand will be sufficient to cover the cost of doing so. Degrowth reduces that confidence.

And for another, technical progress and innovation require competition: a lot of productivity growth comes not from incumbents upping their game, but from new entrants and exits (pdf). But degrowth increases the share of the social sector in GDP and shrinks the share of markets.

We mustn���t be wholly pessimistic, however. We���ve decent evidence (pdf) that cutting working hours ��� at least moderately ��� can raise productivity (pdf). And socialism could remove the barriers to productivity created by inequality and managerialism, not least by encouraging worker coops.

Nevertheless, all this leaves us with a big question: how to reconcile socialism with the competition necessary (but not sufficient!) to raise efficiency? This is made all the more difficult because nobody in British politics seems to be thinking about it*.

But there���s another issue here. Working significantly less is not a change in degree but one of kind. And it���s one many of us will struggle to adjust to. As Maynard Keynes wrote in a famous essay (pdf):

There is no country and no people, I think, who can look forward to the age of leisure and of abundance without a dread. For we have been trained too long to strive and not to enjoy.

Being free from work can mean being free from roles, from meaning: think of the ennui endured by the women in Jane Austen novels or housewives such as Betty Draper in the mid-20th century. I���ve a sense of this myself. I���m planning on retiring next year, but I approach this as my teenage self regarded beautiful girls ��� with desire mixed with fear.

I fear there���s a bigger danger. Recent years have confirmed what Benjamin Friedman wrote in 2006:

The history of each of the large Western democracies ��� America, Britain, France and Germany ��� is replete with instances in which [a] turn away from openness and tolerance, and often the weakening of democratic political institutions, followed in the wake of economic stagnation that diminished people���s confidence in a better future.

The biggest support for the Green party, remember, came in 1989 ��� at the peak of a boom.

Which provides another challenge for degrowthers: how to prevent lower GDP leading to reactionary politics?

If all this reads like a critique of degrowth, it shouldn���t. Rather, my scepticism is directed towards a particular type of politics ��� very often found among centrists as much as on the left - which I���ll call the ���if I were king��� conception. We should not think of policies as standalone interventions imposed from the top down. Instead, they are embedded in, and arise from, particular cultures and configurations of class interests. Policy is endogenous.

I don���t think this is a counsel of despair. It is to say that the left and greens must campaign for the cultural change without which degrowth is impossible. The precedent here is perhaps free market ideas in the 50s and 60s. These were marginalized, but years of often-neglected work by campaigners and thinktanks eventually led to them becoming accepted in the 80s. You can do a lot of important political work without having power.

* The papers cited in this sentence are paywalled ��� hence the links to scihub. Yes, there is irony in this fact.

** I am perhaps unique in believing that the decline in interest in market socialism is one of many intellectual wrong turns we have made in recent years.

October 28, 2021

Government spending, profits & capitalism

Simon Clarke, Chief Secretary to the Treasury, says there has been ���something of a philosophical shift��� in Tory attitudes to public spending. Which poses the question: why?

I���m not sure it is the result of high-falutin and rigorous debate. Instead, I���d suggest something else. To see it, let���s start from the perspective that philosophy follows interests and that the Tory party is emergently intelligent: whilst any individual seems cognitively limited, the party itself has a formidable genius.

If these premises are correct, we have a ready explanation for this ���philosophical shift���. It���s that the health of capitalism, for now at least, requires big government. This is true in several ways. I���ll focus on just one ��� that big government spending is necessary to support profits.

To see my point, recall basic national accounts identities. These tell us that GDP is the sum of consumer spending (C), government spending (G), investment (I) and net exports (NX). It���s also the sum of incomes: profits (P), wages (W), other incomes such as those of the self-employed (O), and taxes on production (T). Rearranging these gives us an expression for profits:

P = (C ��� W) + (I ��� O) + (G ��� T) + NX

This just tells us about the circular flow of income. It says that higher wages don���t necessarily cut profits if workers spend those wages. And it tells us that capital spending is good for aggregate profits, as one firm���s outlays are another���s orders. And so on.

This Is an identity, but it helps organize our thinking.

The lockdown of shops and pubs last year forced us to spend less and save more; the household savings rate, which had for years wobbled between 5 and 10% shot above 20%. And even now it���s above 10%. C ��� W has therefore nosedived (as indeed has investment as projects have been put on hold). Our identity tells us that, on its own, this would have caused a massive drop in corporate profits.

But we saw no such fall, because the government acted. Increased public spending supported the economy and hence profits. We credit such spending with protecting jobs. Which it did: in the absence of such spending, firms would have slashed employment in an effort to protect profits. The point is that capitalism required higher government spending. The ���philosophical shift��� to big government was therefore necessary to sustain profits.

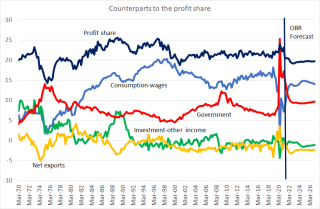

My chart summarizes this, by showing the counterparts in my equation. You can see that in 2020 the C ��� W element collapsed and G ��� T rose, the net effect of which was to actually slightly raise the share of profits in GDP.

And here���s the problem: will we return to the pre-pandemic world in which C ��� W supported profits?

The OBR forecasts (shown in my chart) suggest that we will to a large extent. If foresees the savings ratio falling below 5% by 2024. That would mean a rise in C ��� W which would tend to support profits even if G ��� T falls.

This, however, is far from certain. The fact that retail sales have fallen since their post-lockdown bounce in April suggests we���re a long way from our old spendthrift ways. Some of us have fallen into more frugal habits. Others might need to rebuild the savings they ran down last year as their hours and jobs were cut.

Hence the need to avoid large cuts in public spending. Imposing these at a time when the prospects for consumer spending are still uncertain (and capital spending too) would jeopardize profits. Instinctively ��� emergently ��� the Tories grasp this. Hence their ���philosophical shift.���

But note something else about my chart. It shows that the government sector has for years been a big counterpart to profits, even more so during recessions. In fact, apart from a brief spell in the late 80s, it has far outweighed investment counterpart. This was not always the case. In fact, in the 60s the investment counterpart was bigger.

Now, I stress I���m only talking identities here. Perhaps if the government were to shrink significantly, capital spending would surge and so we���d see sustained profits and a small state. This did not, however, occur during the austerity of the 2010s, perhaps because of what Ben Bernanke way back in 2005 called the ���dearth of domestic investment opportunities.��� The Tories can be forgiven for not wanting to take this risk. There���s a good reason why there are so few libertarians among business lobbyists.

There is, therefore, perhaps a simple and powerful reason (or certainly justification) for the Tories��� conversion to bigger government: it is what capitalism requires.

October 24, 2021

Markets and freedom

One of the great political changes of my adult lifetime has been the right���s abandonment of free market economics, as illustrated by the government imposing trade frictions within the UK and putting up the tax burden to what the OBR says will be ���its highest level since Roy Jenkins was Chancellor in the late 1960s.��� Two books I���ve read recently pose a question: might this shift be due in part to an awareness that markets are no longer the foundation of freedom we once thought they were?

To see my point, let���s start with the classical liberals that so influenced Thatcher. They thought free markets were essential for a free society. As Friedman wrote:

Historical evidence speaks with a single voice on the relation between political freedom and a free market. I know of no example in time or place of a society that has been marked by a large measure of political freedom, and that has not also used something comparable to a free market to organize the bulk of economic activity. (Capitalism and Freedom (pdf), p9)

Or, as Hayek said in The Road to Serfdom, ���a directed economy must be run on more or less dictatorial lines.���

And a market economy is itself liberating. As Friedman put it:

So long as effective freedom of exchange is maintained, the central feature of the market organization of economic activity is that it prevents one person from interfering with another in respect of most of his activities. The consumer is protected from coercion by the seller because of the presence of other sellers with whom he can deal. The seller is protected from coercion by the consumer because of other consumers to whom he can sell. The employee is protected from coercion by the employer because of other employers for whom he can work, and so on*. (Capitalism and Freedom, p14)

Two recent books, however, challenge this perspective. Here���s Martin Hagglund:

To lead a free life it is not sufficient that we are exempt from direct coercion and allowed to make choices. To lead a free life we must be able to recognise ourselves in what we do, to see our practical activities as expressions of our own commitments. This requires that we are able to engage not only in choices but also in fundamental decisions���This is why capitalism is an inherently alienating social institution. To lead our lives for the sake of profit is self-contradictory and alienating, since the purpose of profit treats our lives as means rather than as ends in themselves (This Life, p299-300).

There are (at least) two distinct problems here. One is that free markets are a cover, behind which lie exploitation and oppression. The labour market, Marx wrote, is ���a very Eden of the innate rights of man��� wherein ���both buyer and seller of a commodity, say of labour-power, are constrained only by their own free will.��� Once the transaction has occurred, though, things change:

He, who before was the money-owner, now strides in front as capitalist; the possessor of labour-power follows as his labourer. The one with an air of importance, smirking, intent on business; the other, timid and holding back, like one who is bringing his own hide to market and has nothing to expect but ��� a hiding.

Secondly, markets themselves are a form of what William Clare Roberts calls ���impersonal domination���:

Because they are dependent for their lives upon the market, as slaves are dependent on their masters, producers of wares for sale must keep a ���weather eye��� out for changing market conditions, which are, at bottom, nothing but the will and caprices of their customers and competitors. (Marx���s Inferno, p57)

This dependence afflicts capitalists as well as workers. As Marx famously wrote:

Free competition brings out the inherent laws of capitalist production, in the shape of external coercive laws having power over every individual capitalist.

You might think all this is a mere philosophical debate. Far from it. Four big developments since the 80s vindicate Marx, Hagglund and Roberts against Friedman and Hayek.

One was the financial crisis. This showed that mortgage derivatives ���products intended to reduce risk ��� actually increased systemic risk (pdf) and made the financial system as a whole less manageable. Such products were, in the title of Richard Bookstaber���s book, a demon of our own design.

That phrase echoes perfectly Marx���s idea of alienation, of how man-made structures come to exercise impersonal domination over us:

The object which labour produces ��� labour���s product ��� confronts it as something alien, as a power independent of the producer���It means that the life which he has conferred on the object confronts him as something hostile and alien.

Secondly, casualization in academia, greater stress among teachers and doctors, the rise of bullshit jobs, falling relative pay in journalism and deadly working hours in investment banking are all facets of a single phenomenon ��� the degradation of erstwhile good jobs. People in jobs that were once ���middle class��� experience less freedom at work. Yes, the dark satanic mills have shut and terrible working conditions diminished, but more people now experience labour markets as a front for domination and alienation. And they vote accordingly.

Thirdly, there���s the housing market. In the 80s we young people regarded this as a source of liberation. After just a few years work, we could buy our own place and so free ourselves from the uncertainty caused by dependence upon the rental market. Today���s young people have much less chance. For them, this important market confronts them as an alien force, thwarting their hopes and subjecting them to domination by landlords.

Fourthly, there are globalization and deindustrialization. Many in the US and UK experienced these as causes of and decline, as processes of uncontrolled domination rather than liberation. The vote for Brexit was in large part an expression of frustration by the ���left behind.���

That slogan ���take back control��� tapped in brilliantly to those feelings. To a Hayekian or Friedmanite, the slogan should seem weird: haven���t 40 years of marketization given people more control of their lives? From the perspective that markets aren���t liberating, however, its appeal is clear.

Of course, the slogan took a reasonable feeling and diverted it towards a pointless end. The challenge for our time is to give it more useful expression. How can we increase economic democracy and people���s real control over their economic lives without damaging too much the genuine good that markets do as technologies of allocation? Hardly anybody in politics, however, is interested in this.

* Note that Friedman���s argument only applies to imperfect markets. In the textbook case of perfect competition all sellers and all employers are the same.

October 18, 2021

Productivity in late capitalism

In the debate about how to increase productivity, everybody seems to be making an assumption that I find questionable - that feasible policy changes can make a significant difference.

We need some historical context here. My chart shows that big, sustained productivity growth is in fact very rare; growth of over 2.5 per cent a year was only seen over lengthy periods between 1945 and 1990. Our idea that rapid growth is normal and stagnation not might owe more to the influence of our formative years than it does to the wider historical evidence.

To see why strong growth should be so unusual, imagine an industry could treble its productivity over ten years. If it accounted for two per cent of the economy, it would add less than 0.3 percentage points to total annual productivity growth. This tells us that a few dynamic sectors are not enough to achieve good aggregate growth. Productivity growth was minuscule in the early decades of the industrial revolution because fast-growing sectors were only a small part of the economy.

Which is the problem we face now, in modified form. The economy is dominated by services, in many of which efficiency gains are terribly difficult to achieve: teachers, waiters, care workers and hairdressers have few ways of significantly improving productivity: this is Baumol���s cost disease. As Dietrich Vollrath writes:

Most service industries have relatively low productivity growth, and most goods-producing industries have relatively high productivity growth. As we shifted our spending from goods to services then, this pulled down overall productivity growth. (Fully Grown, p5)

Perhaps, then, strong productivity growth was the aberration and stagnation is the norm. Certainly, this is what classical economists thought. All of them foresaw a ���stationary state��� in which growth ceased because the forces of diminishing returns outweighed technical progress. As John Stuart Mill wrote:

It must always have been seen, more or less distinctly, by political economists, that the increase of wealth is not boundless: that at the end of what they term the progressive state lies the stationary state, that all progress in wealth is but a postponement of this, and that each step in advance is an approach to it.

Marx���s view that a falling rate of profit would ultimately lead to capitalist stagnation was essentially an elaboration of his predecessors��� thinking: Marx���s admirers and detractors both under-appreciate the kernel of truth in Paul Samuelson���s gibe that he was a ���minor post-Ricardian.���

It���s not just Baumol���s disease and diminishing returns that limit productivity improvements, however. There���s also a collective action problem. Companies will only invest to raise profits if they believe (rationally or not) that there���s a profit for themselves in it. This obviously limits investments that have spillovers: as William Nordhaus showed, firms capture only a ���miniscule fraction��� of the total returns to innovation. It can also curb investment if firms fear that future change will render today���s technologies obsolete: why spend ��1m on a robot today if it will be competing against a ��500,000 one in a few years��� time? And then there���s the likelihood that a series of crises ��� the tech crash, financial crisis and pandemic ��� have depressed animal spirits.

All this means that even if productivity-enhancing technologies are available, companies have good reason not to use them.

There���s another obstacle to productivity growth. As thinkers such as Mancur Olson and Joseph Schumpeter pointed out, economic growth produces powerful groups with vested interests in blocking further progress. Joel Mokyr calls this Cardwell���s law:

Technological progress encounters resistance from various groups that believe they stand to lose from innovation. These pressure groups will try to manipulate the political system to suppress successful innovation���.Under fairly general conditions, it can be shown that the single economy will move inexorably to an absorbing barrier of technological stagnation.

So, for example, big companies push for harsh intellectual property laws to preserve their monopoly profits, at the expense of expanding knowledge: there���s a reason why that link to Mokyr���s paper takes you to Scihub. Bosses prefer to use new technologies for surveillance and guard labour (pdf) rather than for expansionary or liberationary purposes. And bankers want high-powered incentives that boost their incomes even if these come at the risk of financial crises that contribute to years of stagnation.

Such conservatism is especially restrictive in our rentier-dominated economy. Rentiers oppose some changes that might raise productivity, such as shifting taxes from incomes to land. They also want low interest rates rather than the high aggregate demand that might drive productivity gains. In the post-war years General Motors needed a large well-paid working class; the latter-day Goldman Sachs does not. All of which blocks productivity improvements because it is this minority of people who have disproportionate political power.

There���s a reason why Johnson���s attempt to raise productivity by restricting immigration is so daft: more intelligent ways of doing so are countermanded by our political system.

All of which suggests that Marx might have been right:

At a certain stage of development, the material productive forces of society come into conflict with the existing relations of production or ��� this merely expresses the same thing in legal terms ��� with the property relations within the framework of which they have operated hitherto. From forms of development of the productive forces these relations turn into their fetters.

Capitalism was once a progressive force, but ��� especially perhaps in the UK ��� it no longer is. And this is due not to external shocks but to endogenous developments.

The point of this is of course not to say that if we had a revolution we could all live happily ever after. It is instead to pose a challenge to anybody discussing the UK���s productivity problem. It���s not sufficient to ask what measures might raise productivity: there are countless good candidates. We must also ask: are those policies possible within the constraints of the UK���s political system? Technocrats must take class politics more seriously.

October 14, 2021

The house price puzzle

Everybody knows that the housing market has become financialized, as Josh Ryan-Collins among others has documented. But what kind of financial asset is housing? The answer is far from straightforward.

In one sense, house prices are like share prices. Both are claims upon future incomes ��� profits in the case of equities and wages in the case of houses (it���s fair to assume rents are a stable fraction of wages). Both tend to fall in recessions. And both have over the years delivered a risk premium ��� though how great depends upon which time period you use, how you account for liquidity risk and so on.

But there���s a massive difference between house prices and share prices.

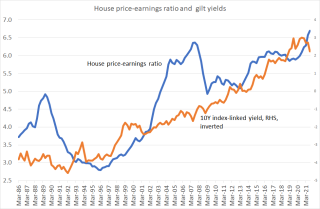

Since the mid-90s house price valuations have soared. In 1998 the average house prices was 3.1x the income of first-time buyers according to the Nationwide. Today it is 6.7x. Equity valuations however (at least in the UK) have not much changed in this time. The ratio of the All-share index to dividends or earnings is much the same as it was in 1997-98. In this sense, house prices have behaved far more like bonds than equities: they have risen as interest rates have fallen whereas share prices have not.

There���s an obvious explanation for this. Lower real interest rates raise the net present value of future rents (or of rents saved if you are an owner-occupier) so they raise house prices. As Bank of England economists say: ���the rise in real house prices since 2000 can be explained almost entirely by lower interest rates.��� My chart shows that there���s a huge correlation between the house price-earnings ratio and the ten-year index-linked yield. House prices, then, have behaved like bond prices. And if it walks like a duck and quacks like a duck���

In theory of course, a lower discount rate should have also raised share prices. I suspect it hasn���t because the same stagnation and risk aversion that���s pushed bond yields down has depressed expectations for dividend growth and increased the risk premium investors demand on equities.

But why haven���t these same factors also depressed house prices? Surely increased risk and the prospect of lower rental growth should be bad for them?

The answer might be that, in fact, housing is a safe asset just like a bond.

One way in which this is true is that protects us from future rises in rents: the demand for owner-occupation is a demand for rent control. Also, as Cristian Badarinza and Tarun Ramadorai have shown, foreign investors have regarded the London housing market as a safe haven (pdf) from economic and political risk ��� just as they regard western bonds.

What���s more, for many of us our house is not wealth so we shouldn���t care if its price falls. And an asset whose price fall doesn���t bother us is similar to one whose price doesn���t fall in the first place.

Put it this way. I grow a lot of kale in my garden, so I never need buy any from the shops. The price of kale therefore doesn���t bother me. If it falls I���m worse off as a kale-grower but better off as a kale-consumer to exactly the same extent. The net impact is zero. As an owner-occupier I���m in the same position. I���m providing housing services to myself. A rising cost of those services benefits me as a supplier and makes me worse off as a consumer with no net effect. As Mervyn King said (pdf) back in 1998:

A rise in house prices leads not only to an increase in wealth but also to an increase in the cost of housing services. Or, to put it another way, if the price of your home goes up, you will not be able to spend more on other things if you wish to carry on living in your home.

This shows that housing like a bond in another sense. A rise in bond prices is ambiguous for bond-holders. Yes, it makes them better off in the sense that their assets are worth more. But it makes them worse off in that they will have to pay more in future to obtain a given income: ���higher bond prices��� is another way of saying ���lower annuity rates���. For many, the net impact is zero.

Obviously, this is not true for everybody. If you are a landlord or someone planning on trading down ��� that is, on consuming less housing services in future ��� rising house prices do make you better off.

Such people, though, are a minority. Atif Mian and Amir Sufi estimate that the boom in housing transactions in the US during the bubble of the mid-00s was driven by the 1% of people who bought and sold many houses quickly. The vast majority didn���t behave as speculators ��� but as Ulrike Malmendier and Adam Szeidl show (pdf) bubbles are generated by minority behaviour.

But for everybody who is long of housing, somebody else is short such as younger people wanting to buy a home. Net, as Willem Buiter pointed out, housing is not net wealth (pdf).

If all this is right, it has an encouraging implication. It suggests that measures to definancialize the housing market such as credit controls, curbs on speculation or land value taxes are ��� from an economic point of view ��� a free hit. They would reduce the economic harms done by high house prices such as increased instability (pdf); lower productivity (due in part to encouraging longer commutes); and greater labour market frictions ��� not to mention the cultural and psychological damage they do. And they���d do so at very little cost: if house prices aren���t net wealth, cuts in them don���t matter.

This is not to say the job is politically easy: the tiny minority for whom house prices are wealth would resist such measures, and it is they who control politics. The point is, though, that what we have here is an obvious cost-benefit win.

But is it right? There���s a different explanation for the contrast between bond and equity behaviour in the face of falling interest rates.

It���s possible that housing speculators have priced in the good news of lower bond yields (a lower discount rate) but not the bad, that they betoken stagnation.

There���s a sort of precedent for this. Back in 1979 Franco Modigliani and Richard Cohn argued that shares had fallen in the 70s because they were only half reacting (pdf) to higher inflation: they were taking on the bad news of higher interest rates and hence discount rates but not the good, that inflation would raise future earnings. Maybe the housing market is also doing some half-pricing in ��� taking on the good news of lower interest rates whilst ignoring what those lower rates symptomize.

If this is the case (and I don���t know if it is) then prices should eventually fall of the own accord. In which case we don���t need policy to definancialize housing: the market will do it anyway.

October 12, 2021

Skill as a social construct

Imagine we lived in a society scared of germs, which prized cleanliness not only as a way of ensuring good health but also of improving productivity as people avoided the sniffles and minor ailments. In such a society good cleaners, who could get a place really spotless, would be highly valued and paid.

This isn���t a wholly fanciful example. In industries that need ultra-clean rooms, such as semi-conductor manufacturing, cleaners are indeed well-paid and valorised. It tells us that the value we attach to jobs is a product of culture. A germophobic culture would regard good cleaning as a skill and pay accordingly for it.

You might think such a culture would be irrational. Maybe, maybe not. But the valuations our current society attaches to some jobs is also irrational. City University���s David Blake has shown that ���the vast majority of fund managers��� are ���genuinely unskilled.��� If we regard skill as a matter of technique, this is correct: they don���t beat tracker funds. But skill isn���t just about technique. It���s about what gets valued. Those fund managers are paid handsome salaries because they are valued even though they lack technical ability.

Similarly, Nick Bloom and John Van Reenen have shown (pdf) that there is ���a long tail of extremely badly managed firms��� and Paul Ormerod and Bridget Rosewell have shown (pdf) that ���firms have very limited capacities to acquire knowledge about the likely impact of their strategies.��� In many cases, therefore, managerial ���skill��� is technically lacking. But their pay suggests otherwise.

Skill, then, is a social construct ��� the result not just of technical ability but of what society values, what it sees (which might not be there), and what it doesn���t see. This is a longstanding theory (pdf) in sociology, but a perspective missing from economics. Economists talk about demand curves and value -added. But doing this they are entering the play during the second act, missing the one that describes the cultural formation of value and demand curves and hence of skill.

For example, in the 1960s the women who sewed car-seat covers for Ford were seen by managers as unskilled and paid accordingly. But in fact ��� and as the women proved ��� such work was difficult. It was seen as unskilled not because it was technically easy, but because it was women���s work. It���s not obvious that such gender-based perception of skill has wholly vanished: it might explain why care work is under-valued.

Ian Hampson and Anne Junor give us another example, that of an education support worker helping a disabled child (pdf):

She had acquired the haptic skills of having a constant ���feel��� for the way the child���s muscle system was coping with spells of standing. She contributed to the stable and happy climate of the centre by unobtrusively managing medication, ambulance calls and feeding without interrupting the f low of class activities. She needed negotiation skills at the level of problem-solving and solution-sharing, to shape other children���s responses and to guide parents. She managed awkward ���upward��� feedback, convincing a higher-status classroom teacher to forego exciting new teaching methods that were actually causing the child to regress. These skills appear mundane, but were subtle sources of social development.

She is, not, though, paid and valorised as a skilled worker.

Philip Moss and Chris Tilly point to another example. Young black men, they say, are perceived as lacking soft skills ��� the sort that don���t carry formal credentials ��� and so are under-represented in jobs requiring these. Just as ���skill��� is gendered, so it is also race-based.

Harry Braverman points (pdf) to yet another example. In the early 20th century, he says, an ability to ride a horse and carriage was seen as unskilled whilst the ability to drive a car was a skilled job. Today, it is the opposite way round.

We might add to all this David Graeber���s theory of bullshit jobs. Flunkies and box-tickers do jobs which they themselves regard as lacking social value. But they are often paid as skilled jobs because they have private value to their immediate bosses who want to build their empires*.

And of course, there is the matter of unpaid care work. Frances Coppola tweeted today:

Underlying the casual assumption that families can care for relatives themselves is a toxic belief that people - especially older women - who give up work to take on the care of relatives aren't productive anyway.

They aren���t productive because of a social construct ��� that in capitalism the only labour that has value, and so is productive, is that done for profit. The wages for housework campaign challenges this ��� and in doing so shows us that other valorizations are possible.

There are several elements of the social construction of skill:

- Marginal product. This approach is entirely consistent with the idea that wages equal marginal product**. It���s just that our ideas of what is a high marginal product are a matter of taste and ideology. In a fabulous paper (pdf) the late Werner Troesken showed that snake oil sellers were highly productive for decades even though their products were mostly useless, making them much like fund managers today. And footballers (and top sportsmen generally) are much more highly valued now than they were in the 60s or 70s. What���s changed isn���t their technical skill ��� Fred is not a better footballer than Bobby Charlton was ��� but our sense of value.

- Payment for the bare minimum. In some jobs, we pay the bare minimum for the bare quality of work. In others, we pay extra for ���talent���. Which it is can be a matter of power and preferences, not just technical ability. For example, although most care-workers are paid the bare minimum, skilled ones can get more by escaping the maw of council sub-contractors and going private. And where ���talent��� is rewarded it is often not actual ability that matters but the fact of having proven that one is just good enough ��� which is why many professions are dominated by mediocrities, as Marko Tervio has shown.

- Management recognition. We���ve all rang up call centres and found that some staff are immensely helpful and efficient and others less so. Such helpfulness, however, doesn���t always bring with it appropriate pay. As Hampson and Junor say, some skills are unrecognised because they ���lack managerial authorization.���

- Avoiding externalities. Oil workers are well-paid and valued ��� if, that is, you ignore the pollution they generate. Similarly, many bankers seemed skilled before 2008 because we under-rated the risk pollution they were generating. And (some) journalists, columnists and rentagobs have private value, because the intellectual pollution they cause isn���t priced.

My point here is that value and productivity are not exogenous technical data. They are instead the product of societal judgments which valorize some activities and de-valorize or under-valorize others.

Which suggests that both left and right are missing a trick. We can raise the wages of the low-paid not by creating shortages or by hiking up the minimum but by a shift in what we valorize and don���t. It���s easy to imagine ��� unless you���ve been captured by capitalist realism ��� a society that is reasonably egalitarian simply because it values cleaners and care workers more and bosses, financiers and bullshit jobs less.

Of course, this isn���t to say we can simply think ourselves richer: I���m talking about relative values here. And of course cultural change takes time. But we should start the process. Which requires us to recognise that skill and productivity are social constructs. And what we build, we can change.

* Graeber���s theory is more economically orthodox than his admirers would want to admit. It���s an example of the point Michael Jensen made in 1989 ��� that listed companies with dispersed shareholders have inadequate oversight of managers who can therefore pursue their private interests at the expense of shareholders. These interests might include building an empire of bullshit jobs.

** It���s also consistent with Marx���s theory. There���s a reason why he equated value with *socially* necessary labour-time.

October 3, 2021

In search of the centre ground

In the FT, Robert Shrimsley writes:

Starmer is leading his party back to the centre ground and has positioned it where it needs to be and patently was not under Jeremy Corbyn���.The problem in contesting the centre ground is that you do actually have to fight for it and the Tories will not lightly surrender.

This poses the question: what is this centre ground, and how can it be said that the Tories occupy it?

It���s a puzzle.

We could define the centre ground as being what the median voter believes. But the majority of voters want a ��15ph minimum wage, higher taxes on the rich, and nationalization of railways and utilities. From this perspective, Starmer is leading his party away from the centre ground which Corbyn and McDonnell claimed ��� a ground which the Tories don���t occupy.

Clearly, Shrimsley doesn���t have this conception of the centre ground in mind.

But there���s another. It arises from the theory of valence politics.

This says that voters don���t judge parties by the entirety of their manifestos, which only cranks and obsessives read. Instead, they judge parties, and especially leaders, by their performance on what they care about most.

On this view it can be said that Corbyn abandoned the centre ground, despite having many policies popular with the median voter. Median voters saw him as unpatriotic and as unable or unwilling to get Brexit done, defects which outweighed his attractive economic policies. Johnson could thus seize the centre ground in 2019.

But there���s more to valence politics than this. As Peter Kellner has said, valence voters

judge parties and politicians not on their manifestos but on their character. Are they competent? Honest? Strong in a crisis? Likely to keep their promises?

Johnson does not occupy the centre ground on these criteria. But then, nor does Starmer. As Kellner wrote recently: ���the average ���valence��� scores of the two parties are dreadful.���

On this conception, then, nobody in England commands the centre ground.

And, perhaps, nor could they. Median voter theory assumes that voters are distributed along one dimension ��� traditionally left and right ��� and so there is some kind of centre: the theory is closely analogous to Hotelling���s Law. But this might be changing. If voters are divided along other dimensions, such as culture or age, the centre ground becomes much harder to define ��� which is perhaps why the Lib Dems and ChangeUK lost so heavily at the last election. In 2019, Labour won among under-39 year-olds but lost heavily among older voters. It won the younger median voter but lost the older one. What does the centre ground mean here?

How, then, can Shrimsley be writing anything other than utter guff?

Simple. There���s a third conception of the centre ground.

Which is just the status quo, and minor tweaks thereto.

In the 60s and 70s, for example, the centre ground believed that utilities should be publicly owned. By the late 90s, it believed they should be privately held. And before 2016 the centre ground supported UK membership of EU single market. Now, it opposes them. It is in this sense that ���Starmer is leading his party back to the centre ground��� ��� by abandoning support for freedom of movement.

Centrism, then, is parasitic and deferential to the existing order.

These different conceptions of the centre ground explain the intellectual trajectory of centrists during my adulthood. In 1983 the SDP manifesto wanted a fiscal stimulus to cut unemployment and raise welfare benefits, increased foreign aid and ���a major extension of profit sharing and worker share-ownership.��� Centrists today are just gimps for billionaires.

This transformation happened because the SDP were using a median voter conception of the centre ground; they tried to split the difference between left and right as they existed at the time. Today, though, centrists see no need to stake out a defined position between left and right. ���Moderation��� means accepting the status quo.

When columnists like Shrimsley speak of the centre ground, therefore, what they mean is merely ���something that doesn���t scare me���.

From this perspective, Starmer is indeed returning to the centre ground, by not challenging the existing capitalist order. However, it is one thing to actively argue for the status quo and another to merely passively accept it without intellectual effort, as Starmer is doing. Worse still, defending capitalism when it is delivering rising living standards and better jobs (as centrists could plausibly claim in the 90s) is very different from defending it when it has delivered a generation of crisis, rentierism, and stagnation. The centre ground is now just a fetid swamp.

September 28, 2021

The minimum wage dilemma

Should the national living wage rise to ��15 an hour? For me, it���s a dilemma because there are two competing and powerful perspectives.

The economic perspective is sceptical. Econ 101 says a higher price means lower demand, so a higher minimum will lead to job losses or ��� just as importantly but often overlooked ��� cuts in hours.

Granted, Econ 101 might be wrong. Where employers have monopsony power, a higher minimum wage can lead to employment actually increasing.

Which leads us to the thorny question of empirical evidence. Here, we have a problem. It���s possible that previous rises in the minimum wage have had little effect upon labour demand simply because they have been small ��� enough to generate favourable effects by reducing monopsony but not so big as to have the effects predicted by Econ 101*. It���s like taking paracetamol; one or two will make you feel better, but it does not follow that a whole bottle will make you even better.

What we need, then, is evidence from big rises in minimum wages. Much of this comes from Seattle, which gradually raised its minimum from under $10 an hour in 2015 to $15 this year.

Sadly, this evidence is mixed. Some has found (pdf) no adverse (pdf) employment effect (pdf), whilst other research has found that hours (pdf) worked fell and prices rose. And other research suggests that big rises rises in minimum wages do cut jobs (pdf) even though small ones don���t.

Net, the economic perspective, I suspect, says that a ��15 minimum wage would be a risky experiment.

But it is not the only perspective. There���s another one. It says that pay is not just a matter of technical skill and effort ��� much minimum wage work requires lots of both ��� but of power. ���Skill��� is a social construct. People are low paid because they lack power and because society grossly undervalues some types of work ��� not least the sort traditionally done by women and minority workers. And because we tend to equate people���s worth with the worth of their labour-power, this means that some people are devalued. A higher minimum wage is an attack upon these inequalities.

Herein lies my problem. If we take only the economic perspective we are guilty of capitalist realism, of failing to imagine an alternative to inequalities. But if we take only the latter perspective, we are guilty of at best wishful thinking and at worst recklessly endangering the livelihoods of the worst off.

So, can we combine both perspectives?

Perhaps.

Part of the answer is to regard a higher minimum wage not as a standalone, isolated technocratic fix but as one of a suite of policies to improve life for the worst off.

The most important of these is to run the economy hot, to achieve genuine full employment. One reason why some of those Seattle studies have not found adverse effects of jobs is that the economy was booming as the minimum wage rose. As Dan Davies has said, whatever your preferred social policy objective is, full employment is a good way to achieve it. But we should add into the mix in-work income support (say through a basic income) to mitigate any loss of hours and stronger trades unions. Personally, I regard minimum wages as a second-best, a means of achieving what would in a better world be done not through state diktat but collective bargaining.

There���s something else. What we also need is a revalorization of work, that recognizes the worth and merit of those who clean up after us. We don���t try to employ bosses or TV presenters on the cheap, so why should we think we can get social care or meals out on the cheap?

Of course, all this poses deep questions. How ��� if at all - can we effect such a big cultural change? Are higher wages in the interests of capital (because they might raise aggregate demand) or not ��� that is, is wage-led growth feasible? And how might we counter the potential inflationary impact of full employment and higher wages, for example by spreading profit-sharing?

Frankly, I don���t know the answer to these questions. But I do know two things. One is that they should be asked and answered by cleverer people than me. The other is that we should at least acknowledge the dilemma created by that clash of perspectives.

* Even this might not be wholly true, though. A recent paper (pdf) found that ���employment growth from 2015 to 2018 was in the region of 2 or 3 percentage points lower in firms affected by the introduction of the National Living Wage.���

Chris Dillow's Blog

- Chris Dillow's profile

- 2 followers