Chris Dillow's Blog, page 6

February 24, 2023

Three types of "error"

It's often the case that sport can give us lessons for other walks of life. So it is with Mikel Arteta's recent reaction to Lee Mason's failure to draw the lines on the TV replay which would have shown that Brentford's equalizing goal was offside. He said:

That wasn���t a human error���it was a big, big, big, not conceiving or understanding your job. That���s not acceptable.

This distinction is a nice one. In environments where there is uncertainty, time pressure and incomplete information human errors are inevitable and thus forgivable (although the history of the airline industry shows they can be reduced). What's less forgivable, though, is just not understanding your job. We often see this in football; the player who mishits a backpass or misses an easy chance will usually be consoled by his team-mates whilst the one who fails to mark his opponent or track his runner will be criticized.

This distinction also applies in finance. The fund manager who picks a quality defensive stock might under-perform. But that's a human error. He at least understands his job - because we know that such shares in general on average do in fact beat the market. By contrast, the fund manager who buys a spivvy Aim stock and loses money is not even understanding his job, because Aim stocks on average under-perform badly, perhaps because investors systematically pay too much for lottery-type shares: the Aim index is lower now than it was in 1997 whilst the All-share index has almost doubled.

The failure of Neil Woodford's funds was, I think, a case of not understanding his job. Buying under-performing shares is mere human error. But Woodford's error was more culpable. He held illiquid stocks in an inappropriate vehicle - an open-ended fund - which meant that when investors wanted their money back he couldn't give it them.

This error was compounded by another failure of understanding the job - that the task of decision-makers must be to avoid egregious and well-known mistakes. One of these is that past success often makes people dizzy with success, with terrible effects. Woodford was following a pattern: Goodwin's success at taking over Nat West made him think he could do the same with ABN Amro, and Cameron's victories in the 2014 Scottish independence referendum and 2015 general election emoboldened him to think he could win a Brexit referendum. Both ended in disaster.

We should view policy mistakes through this same distinction. Some mistakes are inevitable and forgivable because of what Thomas Homer Dixon called an "ingenuity gap": there's a gap between the vast complexity and unknowability of the world and our puny knowledge.

I'd put some of the Covid reponses into this. Not locking down earlier when we first knew about the virus might well have been an error in retrospect. But it was a forgivable one: Covid was a new and unfamiliar threat.

Similarly, the Bank of England's failure to keep inflation down is also a partly forgivable error. It could not have foreseen the surge in oil and gas prices following Russia's invasion of Ukraine, and even if it had done so it could not have raised interest rates to the level needed to keep inflation at two per cent without inflicting massive damage on the economy. Yes, it might have raised rates in anticipation of mismatches between supply and demand driving up prices, but even had it done so inflation would now still be way above target.

What are not so forgivable, however, are fiscal policy errors. The purpose of fiscal policy is not to enact the voices in your head. It is to respond to economic facts on the ground. Failing to see this is to fail to understand the job of being chancellor. Which is what Kwarteng did in announcing a tax-cutting Budget at a time when markets were worrying about inflation.

And not just Kwarteng. Tight fiscal policy in the early 2010s when there were unemployed resources and interest rates were at their lower bound was also a misunderstanding of the job of chancellor - that looser policy is warranted in such circumstances.

Tory fiscal policy has been like Eric Morecombe's piano-playing; the right notes, but not necessarily in the right order*. Just as the one misunderstands the job of the pianist, so the other misunderstands the job of policy-making.

Useful as it is, Arteta's distinction is not a complete one. We might add a third type of error - that of professional deformation, that professionals are trained and selected to have a particular worldview. Politicians, lawyers and - yes - economists all have distorted views of the world by virtue of (and perhaps because of) understanding their job.

Journalism is an important example of this problem. A lot of what is wrong with it is due not to human error or to obeying the orders of billionaires. They are instead an inherent product of the profession of journalism itself: a bias towards individual agency and against emergence; towards human interest rather than statistics; towards individual events rather than slow-moving trends; and towards over-selling stories. Such biases exist even if the journalist is doing her job properly: journalism is not social science, and cannot give us an accurate picture of the world.

There's another problem here, inherent to our language. We apply words such as "error" and "mistake" to policy-making, forecasting or stock-picking as if we were teachers putting a red cross next to an exam answer. But this is sometimes wrong. In an uncertain world, nobody has the right answers except perhaps in hindsight. We need a different word, for a "mistake" which is inevitable and forgivable. Until we get one, we must ask other questions, the answers to which will vary from context to context. To what extent can human errors be reduced by better training and selection? Or might such training actually introduce other errors? Which errors would persist simply because the world is complex and our knowledge limited? And, if errors are inevitable, how can we ensure we are resilient to them, and which ones would we rather make - because in our complex world, this is sometimes all we can do?

* A pedant writes: technically, he wasn't, as he was playing in different keys.

February 21, 2023

Anti-business

Rachel Reeves claims to be "pro-business." At risk of mistaking a vacuous cliche for a serious proposition, I'm not sure she should be.

It's not obvious that business has intrinsic virtues. Yes, some businessmen are genuinely committed to virtues of excellence even if they don't use that MacIntyrean term, but equally business is a location of hierarchy, unfreedom, bullshit jobs and bullshit language.

What's more, the single-minded pursuit of short-term profit often displaces such virtues. It can crowd out altruism or professional pride; incentivize managers to chase a quick buck through fraud rather than by promoting a healthy corporate culture (pdf); encourage risk-taking; and reduce creativity (pdf).

Equally, whilst businesses can be part of a healthy market environment, they can also undermine that environment by bribing government, seeking special favours or hiding behind intellectual property laws that restrict competition. It's not obvious that governments should be pro-businesses such as PPE Medpro, Relx or Capita.

Instead, if we should be pro-business, it is because business is a means to achieving other things, the most obvious of which is prosperity.

Now, all economists agree that the determinants of a nation's prosperity are capital, labour, technology, institutions and culture. Which poses the question: to what extent do businesses contribute to these?

For years - long before Brexit - the UK has had low capital investment and a lack of vocational skills. Which tells us that businesses' ability to grow the first two of these has been limited.

But a more interesting case is technology. The best companies have organizational capital; they are more productive than you would imagine from looking only at the capital and labour they employ. Compare, for example, Amazon and Evri. There's not much difference between their drivers and vans. And yet Amazon is an excellent at delivering goods and Evri less so. It has organizational capital, an ability to do things with capital and labour that other firms cannot. It is more than the sum of its parts.

We have a rough way of measuring investors' assessment of such organizational capital. It is the ratio of the share price to book value, the value of a company's capital stock. For years, Amazon's price-book value has been high, meaning that investors have considered it to be worth much more than the sum of its parts. In this sense, the Amazon business adds value by doing clever things. So too do other big tech companies such as Microsoft or Apple*.

It makes sense to be pro these sorts of business; they create wealth by being good businesses, not simply by buying capital and labour power.

But not all busineses are like this. Many don't so much create wealth as divert it. Fund managers are mostly quacks and snake oil salesmen whilst banks are mainly property lenders with casino sidelines. They are, as Adair Turner said, socially useless.

This is especially the case for utility companies. Water companies pour shit into seas and rivers; gas and electricity suppliers rip off their customers; and train companies cancel thousands of services, meaning they fail in their basic duty of getting capital and labour in the right place. There's no reason we should be pro these.

Put it this way. If E.On or EDF were to disappear tomorrow, what would we lose? As long as we have electricity and gas production and distribution - that is, real resources and technologies - not much. Such companies are no more than the logo and letterhead to whom you send your bill.

Even outside of egregious cases such as these, many firms destroy value. Many - including household names such as National Express, Vodafone or Saga - have low price-book values, suggesting that the market thinks they subtract value from the resources they employ (though of course whether the market is right is another matter).

You might think such inefficiency will be corrected by market forces either by product market competition driving out bad businesses, or by them being taken over. But this does not happen in those sectors such as utilities where competition is absent. And it happens only weakly in other markets. As Nick Bloom and John Van Reenen have shown, there is a "long tail of badly managed firms". Yes, there's a case for strengthening market forces to ensure that competition is stronger, but this only reminds us that pro-market policies can and should be anti-(some) business ones.

Which brings us to the nub. If Labour is serious about boosting trend growth - and it should be - then it needs policies which are anti-business, or at least anti some businesses. Tougher competition policy would be bad for incumbent businesses but would foster the creative destruction necessary for productivity growth. A shift from taxing profits to taxing land would be anti businesses that own commercial property but would perhaps incentivize productive capital spending. Encouraging alternative means of financing start-ups (such as a state investment bank) would be anti-bank - more competition for them - but pro-entrepreneur. And encouraging worker democracy would be anti-business in the sense that it would undermine the power and self-regard of the worst sort of bosses, but we've good evidence that it would (pdf) raise productivity.

Labour should be pro the small shop confronted with a rapacious landlord; pro the pub or restaurant owner being ripped off by the utility company; and pro the start-up struggling to raise finance from a dysfunctional banking system. It should not be generically pro-business - and in fact given conflicts of interests such as these it cannot be.

Of course, there's isn't always a conflict between policies that are pro-growth and those that are pro-business. Rejoining the single market, for example, would be both; that Labour is not advocating this suggests its embrace of pro-business principles is mitigated by other considerations.

All this should sound familiar. For one thing it is bog-standard conventional economics: proper economics, remember is not the free market fairy tale of Tufton Street but an analysis of how the real world operates. And for another, it echoes Ed Miliband's distinction between producers and predators.

And yet his distinction was howled down by his opponents in the Tory party and (what is much the same thing) the media. Perhaps Reeves has to retreat behind mindless cliches because she knows that intelligent political discourse is not possible.

* A high PB ratio is often a sign that a company has a lot of intangible assets. But such assets are at least sometimes how they create value - a knowledge of how to do clever things with assets that other companies cannot.

February 12, 2023

Lee Anderson & the nature of politics

Lee Anderson's promotion to deputy chairman of the Tory party highlights an under-rated fact about politics - one which perhaps the right understands instinctively better than the left.

Defenders of his elevation claim that Anderson represents interests and ideas that would otherwise be underweighted in Westminster politics. Matt Goodwin points out that Anderson, unlike an increasing number of Labour MPs, had a "working class" job before entering parliament. Dominic Lawson says he "speaks for millions". And Dan Hodges says:

It's important we have voices like Lee Anderson as part of the political mainstream. 52% of voters support the death penalty in certain circumstances. You can't just say to half the electorate, "sorry, we're excluding you lot".

Even if we allow for the tendency for some posh rightists to project their own reactionary attitudes onto a partially-imagined "white working class", there is a germ of truth in this.

But it inadvertently reveals a bigger truth - that politics is not a matter of rational debate about issues we agree to be important, but rather is a struggle for what gets discussed; whose ideas are represented; and whose interests are given mainstream voice.

The thing is that there are hundreds of interests, people and ideas which are underweighted in mainstream politics. I don't just mean identities: women and young people are under-represented in parliament, though less so ethnic minorities and gay people. I mean people such as the disabled, those with special educational needs or others who are dependent upon dwindling local government resources; low-wage workers; tenants facing lousy landlords and exorbitant rents; people with mental health difficulties; those who need probabation services; those dependent upon public transport; or single parents. The recent Dilnot-Blastland report (pdf) showed how the BBC's coverage of the public finances was distorted because it neglected interests such as these.

What's more, there are countless ideas which are under-weighted in Westminster in part because MPs and journalists are selected not to have them - such as the importance of emergence; the fact that work is for millions futile drudgery; the importance of bounded knowledge and rationality; the fact that capitalism constrains policy-making; or that top-down managerialism is not the only model of decision-making. Ideas as different (and I think important) as Oakeshottian conservatism, Ricardianism or free market egalitarianism don't get the attention in politics they should. Nor do many important questions such as why the UK is such a poor country, or why our politics is so anti-intellectual and philistine.

All of which poses the question. Why are Goodwin and Hodges (and Sunak and most of the Tory party) so keen that reactionary older people get a voice and yet so unconcerned that countless other voices are not being heard in Westminster? To put this another way, why is it so important to hear from ex-mining communities now when it was important not to hear from them in 1984-85?

The answer is that the right are not interested in the democratic ideal of equal representation for everyone. They want the likes of Anderson to have a voice precisely so that other voices are not heard. If we are debating the death penalty or immigration or travellers we are not debating other things such as falling real wages, stagnant productivity, the social murder that is austerity or the failure of British capitalism. And guess who that suits?

The right is engaged in a Gramscian war of position, wanting to promote reaction and silence the left, the powerless and (a more recent development) intellectuals. Of course, many on the right don't want to appear so oikish as to actually express Anderson's views themselves. For them, Anderson is a sort of ventriloquist's dummy, a comic entertainment saying what they cannot bring themselves to.

Herein lies the danger. In taking Anderson at face value the left risks being sucked onto the battlefield the right wants - that of culture rather than economics. But then, to quote Orwell out of context, "so much of left-wing thought is a kind of playing with fire by people who don't even know that fire is hot."

February 10, 2023

Weird politicians

Our political system is dysfunctional. It selects for the incompetent, the dishonest and the downright deluded.

So much is obvious to those who care to think about it. What's not so obvious is that there is a more subtle bias in politics which distorts and diminishes political debate.

Recall that all institutions are selection devices: they select for some people and ideas and against others by filtering out some types and by disproportionately attracting others. Even if we had a well-functioning system which selected against crooks, fools, narcissists, egomaniacs and sociopaths our politicians would still be unrepresentative of the people, even of educated and informed people.

To see this just ask: what sort of people are attracted to political careers?

In a well-functioning polity, the answer would be (and in fact is for many MPs now): those who think politics matters, that it can make a difference. If you think it can't - either because a ��2.5 trillion economy is hard to change, or because the power of capital constrains reform, or whatever - you'll choose a different career.

And what sort of folk think that politics can make a difference?

Those who are overconfident - if not about their personal abilities then about the potential for small policies to have large effects; or about the ability of policy-makers to escape the constraints imposed by capital; or about their ability to overcome bounded rationality and knowledge; or about the potential for "good chaps" to stay in charge of government.

Such overconfidence will have systematic effects. It will lead to a neglect of the need for policies and institutions which are resilient to error so it will (for example) underweight the need for automatic stablizers in the belief that policy-makers are smart enough to use discretionary policy to prevent recession. It will cause them to favour tricksy policies such as tax credits or corporation tax over simple ones such as a basic income or land value tax because they over-rate their ability to design and implement complicated policies. It will cause a bias towards belligerent foreign policy by underweighting the risks of intelligence or military failures. And there'll be a bias against freedom because, as Hayek said, "we will rarely know what we lose through a particular restriction of freedom" - and overconfident policy-makers will not be awake to the limits of their knowledge.

Closely related to the faith in policy is a belief that the economy and society can be managed from the top down whilst under-appreciating the importance of complexity and emergence. Marx thought that "the emancipation of the working classes must be conquered by the working classes themselves" - that socialism would be an emergent process. Parliamentarians, by contrast, have been squeamish about such agency. As Ralph Miliband put it, they have "treated the voters not as potential comrades but as possible clients." Labourism, says Phil Burton-Cartledge "was born for the compromises, Byzantine procedures, and plodding constitutionalism of the House of Commons."

In the party, this has for years meant a hostility to "extraparliamentary" action. As Miliband put it in Parliamentary Socialism:

The leaders of the Labour Party have always rejected any kind of political action (such as industrial action for political purposes) which fell, or which appeared to them to fall, outside the framework and conventions of the parliamentary system. The Labour Party has not only been a parliamentary party; it has been a party deeply imbued by parliamentarism.

This is echoed today in Starmer's ambivalence towards railworkers' strikes.

It also means the party has accepted managers' right to manage. We saw this particularly in Gordon Brown's acquiescence to bosses in the belief - refuted by the financial crisis - that they had especial skills of foresight and control. And as Phil says, for Labour economic issues have traditionally been "about 'fairness', not contesting the employer's right to run matters as they see fit." The party has long been wary of economic democracy for this reason.

For the same reason politicians also have a bias against free markets because these too are emergent processes; the creation of private sector monopolies is not, remember, the same as the creation of a market.

Not that this under-weighting of emergence is confined to Labour. Far from it. It is one of the more egregious examples of BBC bias. The BBC has long neglected slow-moving emergent processes such as the productivity stagnation and has failed to see that government borrowing is the counterpart of private sector decisions to save or (not) invest: it is emergent.

This overconfidence in top-down control can have fatal effects. The Chilcott report found that one reason for the failure of the Iraq invasion was that over-optimism "can prevent ground truth from reaching senior ears."

Sometimes, however, it is through small windows that we see a big picture. So it is here. Politicians and political journalists are avid consumers of political biography and have less interest in the social sciences. That fits with overweighting the potential for "great men" to change events whilst underweighting socio-economic forces.

There's something else. The problem with politics is that, to paraphrase Michael Walzer, it takes too many evenings. Professional politicians must attend to their constituents and various hobbyists with bees in their bonnets. They are therefore selected to be busy cunts, to borrow Jaap Stam's famous description of the Neville brothers. It's no surprise, therefore, that all politicians value "hard working families" and neglect Bertrand Russell's essay in praise of idleness. Nor is it surprising that they regard increasing numbers of over-50s leaving work as a problem rather than as something to be celebrated - people being liberated from drudgery and hierarchy.

If your evenings are consumed by political meetings, you can't go to concerts,watch TV or read. Politics will therefore select for philistines. Hence the cuts to arts funding; squeezing of music and arts out of schools; and destruction of adult education.

My point here echoes Peter Allen's The Political Class. Politicians are unrepresentative not just because they are disproportionately male, stale and pale but simply because they are politicians. All professions tend to have a partial and distorted view of the world merely by virtue of attracting particular types and developing particular ideas and dispositions. Politicians are no different.

Except, I suspect, that it is harder for them to see it. The tendencies I've described aren't confined only to MPs, but also to many political journalists and the talking heads who appear on those speak your branes shows. They are therefore reinforced by echo chambers and groupthink. Fish don't know they are wet.

This is not to say this view of the world is wholly wrong. It's not: sometimes moderate top-down reforms do work. Nor is it to say that all MPs and political journalists share all of these dispositions. They don't; it's just that they are more prevalent among the political class than the general educated public.

And - what is important - this would be the case even if there were no nepotism in journalism or rigging of the choosing of parliamentary candidates, and even if politicians were intelligent, rational and well-intentioned. It's simply the result of selection effects - effects which are inherent in even the best-functioning representative democracy. Which is why there's a case for considering alternatives such as sortition and deliberative democracy.

January 30, 2023

Cargo cult economics

In the first pages of After Virtue Alasdair MacIntyre imagines people trying to revive science after it has been destroyed by catastrophes and know-nothing governments. They would, he said, have only fragments to build upon; bits of theories unrelated to other bits or to experimental evidence; and partial ideas unrelated to their context. They would use scientific words but the beliefs and evidence behind such words would be missing.

This, I fear, is the state in which economics has fallen in politicians' hands. They use economicky words, but stripped of the context and evidence in which such words made intelligent sense.

Here are some examples of what I mean.

Tax cuts.

The FT reports that, despite the evidence of the Truss-Kwarteng Budget, some Tory MPs still want tax cuts. Such demands might have made sense in the 60s and 70s, when top tax rates were so high that it was at least plausible that we were on the wrong side of the Laffer curve. And they might also have been sensible when public services were adequately funded.

But neither condition now holds. Tax rates are quite possibly below (pdf) their revenue-maximizing levels (pdf). And even if they weren't, the dire state of the NHS, local government and legal system mean that any future government would have to reverse tax cuts. Fearing cuts would only be temporary people would not change jobs or boost spending in response to them, and so they would not increase growth so much.

"Tax cuts", then, are words cut off from the context in which they made sense.

Profit maximization.

Milton Friedman famously argued (pdf) that "the social responsibility of business is to increase its profits". That was a tenable view when companies were constrained from egregious exploitation by strong unions, competition or regulation. In a world where these constraints are weak, however, a relentless pursuit of profit leads to shit in rivers and seas, terrible service and degrading working conditions.

Incentives.

High-powered financial incentives might sometimes adduce better performance. But they can also encourage reckless risk-taking (pdf); crowd out other motives such as professionalism or altrusim; discourage creativity; encourage fraud; or distract managers from important but difficult-to-measure tasks (pdf). It all depends upon detailed context. Idle talk of incentives cut off from precise individual context is mere handwaving - and often ideologically-motivated hand-waving.

Bashing trades unions.

This was a plausible position in the 1970s when profit margins were squeezed, leading to lower investment, and when regular strikes hampered productivity. Nobody, however, believes these conditions apply today.

None of this, however, is to say that context-free pseudo-economics is confined to the right. Here are two examples on the left.

Nationalization.

There's a tendency to see this as a solution in itself, echoing what James Scott in his marvellous Seeing Like A State calls "high modernism" - an overconfidence in the ability of the state to manage complex systems from the top down. Such a view - though now discredited - made sense in the context of the 1940s and 50s when wartime planning (plus the apparent success of the Soviet Union) lent it credence.

But this is not the context we live in now. We know that nationalized industries, in Tory hands, can be used as a weapon in the class war - to defeat unions (as in mining in the 80s), or to enrich their clients by selling them cheaply.

The question, then, is how to avoid this fate - how to ensure democratic control of the nationalized industries. Which also poses the question of what aims nationalization should serve: in electricity, for example, it could be used to shift from marginal to average cost pricing.

The point is that nationalization is not an end, but a means.

Wealth taxes.

Of course, a wealth tax would raise money. But the government does not need money: it can print as much of it as you want. It needs real resources: nurses, care-workers, builders, quality managers and so on. The question is how a wealth tax would release these from the private sector. It would do so if the rich respond to it by cutting their spending. But it won't if they merely run down their savings.

Again, what we have here is an idea out of context. In a context where governments cannot print money (such as in the euro zone), it might make sense. In a British context, however, the case for a wealth tax (if there be one) lies elsewhere - perhaps, in simple vindictiveness.

It's not just in what people say that they demonstrate context-free ideas. What's revealing is also what is not said, what's not on the agenda. Whilst politicians worry about shortages of labour, they are mostly silent about shortages of adequate management - despite the fact that even mainstream economists agree that these are a big cause of the UK's stagnant productivity*. They are stuck in an out-dated context of unthinking deference to bosses and hierarchy.

What we have here is, however, not unprecedented. In WWII some Melanesian islanders saw American soldiers marching and pointing lights towards the sky, after which cargo would be dropped from planes. They inferred that if they did similar things, they too would get valuable goods. They performed rituals, without understanding the causal link between those rituals and actual outcomes. So it is with so much talk about economics: it imitates the words of proper economics, but without comprehension of the circumstances in which such words have meaning or use.

* And perhaps of labour shortages too: some people are retiring early because of stressful work, which itself is caused by poor management.

January 15, 2023

On resilience

Two apparently different things I've seen recently illustrate a common mistake which distorts our thinking about politics and organizations.

First, 30p Lee tried to show that one could eat very cheaply with Tesco's Weetabix. And then when somebody posted a picture of a mouldy Tesla, Musk's incel fanboys claimed the fault was "owner error."

Anderson's mistake is to fail to see that whilst one perhaps could subsist adequately if one were a joyless calculating machine (what a great advert for capitalism), few people are such machines. And Tesla's fans fail to appreciate that even if Teslas do keep well in optimum conditions, few of us are so careful of our vehicles.

The common error here is an inability to see that products and systems must be resilient to human error simply because such errors are widespread and an inevitable part of the human condition.

Risible though these examples are, similar mistakes are common.

Brexiters who complain that Brexit has been poorly implemented should have foreseen the chance that the process would have been undertaken by fallible individuals. In policy-making, implementation must not be a mere after-thought. A policy that only works if everyone is competent is not a serious policy at all.

The same is true of those calling for reform of the NHS. Maybe there is some kind of insurance system which would be an improvement. But this is only a voice in your head. In this world, we must guard against the (high) risk that the task of reforming the NHS will be undertaken by vicious incompetents in hock to US insurance companies.

My call for policy and institutions to be robust to human error is in fact one with a long tradition. Burke famously said:

We are afraid to put men to live and trade each on his own private stock of reason; because we suspect that this stock in each man is small.

Marx said that "the emancipation of the working classes must be conquered by the working classes themselves" because he did not trust individual leaders. (Marx and Burke aren't so unalike).

The US's founding fathers created a system of checks and balances "to control the abuses of government." "If angels were to govern men, neither external nor internal controls on government would be necessary" wrote James Madison, knowing that men were far from angels.

And Warren Buffett has said: "I always invest in companies an idiot could run, because one day one will." He looks for companies that are resilient to human error. The damage caused by such error can be enormous; one cause of the financial crisis was Fred Goodwin's tyrannical management of Nat West.

So, what would a polity that embeds this principle look like?

In some ways, like our present one. There are nine decision-makers on the MPC to help guard against any one of them being fallible. Judges are constrained by sentencing guidelines to avoid rogue ones making erratic decicions. Where markets function well, they eliminate the bad products resulting from human error. And there's increasing use of algorithms because, as Daniel Kahneman and colleagues have concluded, "simple models beat humans" (although of course algos can go wrong because they are made by flawed humans).

But could we do better? Yes. Here are four possibilities:

- A more generous welfare state. In my context, the case for this isn't just that Anderson is wrong and people need an income well above subsistence levels because they cannot budget with maximal efficiency. It's also because fiscal and monetary policy-makers cannot adequately foresee the future which means that discretionary policy is unreliable. Stronger automatic stabilizers - a higher safety net - thus do a better job of protecting is in bad times.

- Improving selection mechanisms. Our media-political institutions select not for the best but for the worst: they attract incompetent MPs and ministers, and filter out intelligent ideas. They thereby magnify our vulnerability to the human factor: the story of Truss and Johnson is one of systemic rather than individual failure. We must think how to reverse this.

- Increasing diversity. Cognitive diversity reduces the danger of us accepting bad policy by ensuring that all views - not just those of narcissists flattering themselves they are "contrarian" - get heard. Institutions that might facilitate this include citizens assemblies and forms of sortition.

- Economic democracy. The UK has a shortage of good managers. Econ 101 says we should economize on scarce resources. We must find ways of reducing our dependence upon incompetent, rent-seeking or hubristic bosses. One way to do so is strong competition policy: in well-functioning markets, bad companies are competed out of business and easily replaced by rivals. Failing that, tougher regulation of financial "services", rail companies or utilities is needed; one lesson of the financial crisis is that our economy was too dependent upon a few flawed individuals. And there's a case for worker democracy too.

I know. All these proposals are vague. I mention them not as a blueprint - there's no point writing a menu if you don't have a kitchen - but to highlight how far short our existing institutions fall from the ideal of ensuring resilience to bad decision-makers.

This issue is, however, off the political agenda. One of the many defects of our political debate is a belief that things will be tolerable if only we could find the right people; this is Bonnie Tylerism, holding out for a hero. This, however, is the wrong question. We should be looking not for good people but for the right institutions, selection mechanisms and processes - devices which would make our economy and politics more resilient to idiots or crooks.

January 11, 2023

The full employment challenge

Many technocrats think the UK is at or around full employment. What they don't say is that this requires some radical thinking about economic policy.

The Bank's chief economist Huw Pill recently said that the labour market so tight that higher interest rates might be needed to cut aggregate demand and inflation. And Sir Keir Starmer says: "We���re going to have to be fiscally disciplined." The only charitable reading of this is that it means he thinks he's going to inherit a reasonably tight labour market (albeit perhaps not as much so as now) and so a fiscal expansion would be inflationary.

Which raises a big problem. Any intelligent government will need many more workers in some sectors: in health and social care; in housebuilding; in insulating homes; or making and installing solar panels and windmills. But where will these workers come from? The answer used to be simple: migrants and the dole queues. If these are not sufficient to supply the extra staff, however, we need something else - to destroy some existing jobs. Rachel Reeves has promised to "create good jobs", but this might require the abolition of bad ones.

At full employment, doing the things we want - building houses, improving social care, greening the economy - means doing less of something else. Progress must be a matter of creative destruction.

Which jobs should be destroyed? It's here that we need radical thinking.

For a long time, many economists have thought that the labour market was micro efficient but macro inefficient. As Keynes said:

I see no reason to suppose that the existing system seriously misemploys the factors of production which are in use. There are, of course, errors of foresight; but these would not be avoided by centralising decisions. When 9,000,000 men are employed out of 10,000,000 willing and able to work, there is no evidence that the labour of these 9,000,000 men is misdirected. The complaint against the present system is not that these 9,000,000 men ought to be employed on different tasks, but that tasks should be available for the remaining 1,000,000 men. It is in determining the volume, not the direction, of actual employment that the existing system has broken down.

If this is the case, then the solution to our problem is simple: higher taxes would destroy private sector jobs generally, thus making room for job creation in priority sectors.

But it might not be the case. There are reasons to think the existing system does seriously misemploy factors of production.

I don't mean that simply that people spend too much on trinkets of frivolous utility, thus creating over-employment in nail bars, takeaway restaurants or in sports car manufacturing. Instead, I'm thinking of five other mechanisms.

Agency failure. The "bullshit jobs" described by David Graeber are a product of this: middle managers would rather expand their empire of underlings than maximize "shareholder value". So to is the guard labour documented by Samuel Bowles and Arjun Jayadev: security guards, supervisors and some of legal system are in employed to ensure that agents (workers) do what principals (capitalists) want. I'd add many fund managers to this category: savers don't know that active managers on average under-perform the market and so employ too many of them.

Wrong policy choices. One obvious example here are the Border Force agents and lawyers needed to enforce an illiberal immigration policy. I'd add the lawyers, accountants and DWP staff employed to cope with an excessively complicated tax and benefit system, and the police required to enforce anti-drugs laws.

Ideology. Skill is a social construct, a product of ideology. Fund managers are considered skilled even though ���the vast majority��� of them are ���genuinely unskilled��� measured by their ability to beat the market. Conversely, care workers are considered unskilled not because they lack technique because they are disproportionately women or ethnic minorities. The result is excessive demand for some workers (many financiers and managers) and insufficient for others.

Externalities. Where the social cost of pollution is unpriced or under-priced, some industries are larger than would be socially optimum and so have too many workers. Standard examples here are those which emit carbon and other air pollutants. But these aren't the only forms of pollution. There's also risk pollution. The costs of financial crises are borne by all of us rather than internalized with the financial system, and so there is excess employment in the sector. Similarly, when Bulb went bust, we all had to pay more, reminding us that privatized utilities might employ more people than necessary. But there's something else. A lot of "journalism" and poshcuntstalkshit programmes are intellectual pollution; they degrade the public sphere and contribute to bad government.

Peer pressure. Robert Frank has shown that some types of consumer spending (such as on big cars) are fuelled by a desire to keep up with the Joneses, leading to excessive employment in those sectors. He advocates a progressive consumption tax to - in effect - ratchet down this arms race.

Here, though, is a problem. Except perhaps in our last case, higher taxes in general will not on their own destroy the right jobs. We need other policies: tax simplification; deregulation in some sectors and more regulation in others; nationalization; carbon taxes and Pigou taxes; worker democracy; cultural change to valorise care work; better financial education; and so on. It's not clear to me, however, that Labour is thinking along these lines, or even is aware of the problem.

Maybe it is right to be. Perhaps the labour market isn't as tight as Pill believes: this is a purely empirical question the answer to which must not be coloured by one's ideology. (The level of unemployment is not a sufficient metric here: what also matters are mismatches between demand and supply). Or perhaps it will be loose by the time Labour takes office.

Herein lies a paradox. In some respects, inheriting a recession would make things easier for Labour. In such a world, it could create jobs in the care sector and green economy simply by fiscal expansion - assuming it has the will to reject moronic talk of fiscal responsibility. Intellectually, there is no challenge here.

If, however, the labour market is tight, decarbonizing the economy and fixing health and social care will require much more thought.

For decades, we've thought of full employment as an ideal. Which in many ways it is: joblessness is a big cause of unhappiness. In a sclerotic, low-productivity economy, however, it also brings with challenges - ones which are largely neglected.

January 9, 2023

The two agendas

During my long adulthood there has been an under-appreciated change in British politics: whereas left and right used to at least agree upon what the issues were, this is now less true.

Historically, left and right disagreed upon economic issues: nationalization or privatization; capital or labour; fiscal or monetary activism; regulation or deregulation; austerity or not. But for all our differences, we at least agreed that these were the big questions.

This agreement, though, has faded. Whist many of us are still pre-occupied by economic questions - how to raise productivity, decarbonize, democratize the economy and so on - many others are not. Their concerns lie elsewhere: in combatting imagined attacks on freedom whilst ignoring real ones; in identity politics; in talk of "diversitycrats", wokeness or "gender identity ideology"; in what should be taught in schools; or in "stopping the boats."

This divide is not wholly a left-right one. There are some on the left who are obsessed with identity politics (albeit far fewer than in the right's fevered fantasies) and others in the Labour party who fret about second-order issues, whilst some centrists haven't abandoned interest in economics. Nevertheless there is, I sense, an overlap between the left-right split and the disagreement about what matters.

Which leaves many of us older economic-orientied leftists befuddled. As Duncan Weldon tweeted:

Worst NHS crisis of my lifetime, dire economic situation and the public policy discussion today is about a maths teaching plan for the mid to late 2020s which we don���t have the teachers to deliver.

To a degree I've not seen in my lifetime, left and right disagree not just about policy but about what the issues are.

Brexit was an example of this. Before 2016, the big division wasn't so much between Leavers and Remainers: such words had no meaning then. Instead, it was between a few rightists who thought EU membership was a big issue and the rest of us who didn't: one of the right's great rhetorical tricks was to call themselves "eurosceptics" rather than what they really were - which was eurofanatics.

Which poses the question: why has this division emerged?

Part of the story is the spread of poshcuntstalkshit programming. The lack of demand and supply of genuine experts means these are filled with "commentators" whose main talent is being able to turn up to a TV studio at short notice. As these are unable to talk intelligently about complex issues - the stalling of productivity growth, fiscal policy; falling real incomes; the NHS's problems - they resort to the drivel one could hear from thousands of golf club gammons.

But there's something else. It's that actually-existing British capitalism - whether you call it neoliberalism, financialization, rentierism or whatever - has failed most people; even before the jump in gas prices real wages were barely higher than they had been 15 years previously. If you are going to talk about economics, then, you must either talk of big change or defend a system that works only for a minority. It's no wonder therefore that many on the right would rather point to a dead cat: Prince Harry is the latest one, but there'll be another along soon enough. "Culture wars" are a product of capitalist stagnation.

With the economy flat-lining, tricky questions arise. Should we allow public services to deteriorate or raise taxes, if so on whom? Do we really want to cut private consumption to make room for more public consumption? Given that higher energy costs mean that the UK is poorer as a country, whose real income should take the hit: nurses and railworkers, or others, and if so whom? In short, who do we throw under the bus?

These are nasty trade-offs. Which many don't want to talk about. This is true more of the centre and right than left: whereas the latter are comfortable demanding higher taxes on the rich (maybe too comfortable) the former don't like to call explicitly for the impoverishment of nurses.

Instead, if they must talk of economics they wibble about electability or a lack of money - which is only slightly less moronic than asking about nationalizing sausages. Better for them that they retreat to the comfort zone of culture wars.

I would read Truss's ill-fated premiership in this context. Although she spoke of being pro-growth and breaking with Treasury orthodoxy, this was mere cargo-cult economics. It was language without substance, and assertion without evidence - for example that tax cuts would boost growth. Instead, it was identity politics - invoking a (partly fictitious) image of Thatcher and appealing to Tory prejudices rather than seriously engaging with genuine issues.

Whatever the reason for this divide about what we should talk about, it has an important implication. One facet of political power is control over the agenda: if we're talking about immigration or trans people or "wokesters" we are not talking about the failure of capitalism. One under-appreciated route through which the media exercise influence is in deciding what it is that we do talk about. Given this, it's not at all clear to me that it is even possible for the BBC to be truly impartial.

December 15, 2022

Why economists need history

Should economists pay more attention to intellectual history? I'm prompted to ask by Jan Eeckhout's book, The Profit Paradox.

His thesis is that, since the early 80s, many industries have become dominated by a handful of superstar companies whose increased market power allows them to enjoy higher profit margins. The result is higher prices than would otherwise be the case which in turn means lower output, lower demand for labour and lower real interest rates. It's not just workers who suffer from this but also smaller companies who face tougher competition from giant firms and higher costs from them too. We should read all this alongside Thomas Philippon's The Great Reversal and Lindsey and Teles' The Captured Economy, both of which also document how American capitalism has become less competitive and dynamic.

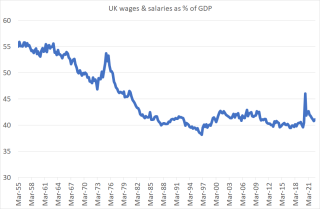

Whilst all this might be true of the US, I suspect it is much less so here in the UK. Of course, we have monopolies, but many of these are privatized rentiers rather than firms like Apple and Amazon that have won the competition for markets. The UK has very few superstar companies - and indeed not many that even reach the height of mediocrity. This much is evident in the fact that the share of GDP going to workers in the UK hasn't changed much since the late 80s yes, real wages have stagnated here for 15 years but this owes more to flatlining productivity than to firms' increased market power.

This, however, is not my beef with Eeckhout. Instead, my problem is that he gives us no historical context.

The idea that capitalism would see increased monopoly power is an old one. Marx wrote that:

The battle of competition is fought by cheapening of commodities. The cheapness of commodities demands, caeteris paribus, on the productiveness of labour, and this again on the scale of production. Therefore, the larger capitals beat the smaller. It will further be remembered that, with the development of the capitalist mode of production, there is an increase in the minimum amount of individual capital necessary to carry on a business under its normal conditions. The smaller capitals, therefore, crowd into spheres of production which Modern Industry has only sporadically or incompletely got hold of. Here competition rages in direct proportion to the number, and in inverse proportion to the magnitudes, of the antagonistic capitals. It always ends in the ruin of many small capitalists, whose capitals partly pass into the hands of their conquerors, partly vanish. Apart from this, with capitalist production an altogether new force comes into play ��� the credit system, which in its first stages furtively creeps in as the humble assistant of accumulation, drawing into the hands of individual or associated capitalists, by invisible threads, the money resources which lie scattered, over the surface of society, in larger or smaller amounts; but it soon becomes a new and terrible weapon in the battle of competition and is finally transformed into an enormous social mechanism for the centralisation of capitals.

And in 1966 Paul Baran and Paul Sweezy argued in Monopoly Capital (pdf) that American capitalism had become dominated by giant corporations with market power, with the result that the economy was stagnating. In essence, that's similar to Eeckhout's theory.

But Eeckhout mentions none of this.

Does this matter? I suspect so.

First, at least some of the monopolistic giants of Baran and Sweezy's time subsequently ceased to be so: think of General Motors, US Steel or Eastman Kodak. This tells us that monopolies are not always as longlasting as they seem. Instead, technical change, competition from unlikely sources, diseconomies of scale or management hubris and over-reach can eventually slay them.

Of course, maybe this time is different. Perhaps companies such as Apple, Alphabet and Microsoft have better economic moats than did 1960s monopolies. But Eeckhout never poses this question - perhaps because that absence of history means it didn't arise.

Eeckhout's omission here is not, however, a personal failing but a symptom of academia. The history of economic thought is not taught as much as it once was. And pressure to publish and to sell books have led to an over-valorization of "original" contributions and thus a failure to locate one's work in an intellectual tradition: the replicability crisis shows us that original work is often not good.

One effect of this is that economists sometimes need to reinvent the wheel. MMT, for example, is in essence the (welcome) rediscovery of functional finance. The result is not only a lack of intellectual progress as we fail to stand upon the shoulders of giants, but also an entrenchment of neoliberal individualism - the selling of research as individual output rather than collective tradition.

But there's something else. Such neglect of intellectual history - and especially the Marxian tradition - leads to naive politics. Eeckhout calls for the establishment of a powerful "Federal Competition Authority" to restrict mergers and promote competition.

But this begs the question: how is such change to be achieved? To paraphrase Marx, this is merely writing a recipe for a cook-shop of the future. Yes, it's valuable in showing that a better world is possible, but it leaves open the matter of how to achieve this world.

Again, this is not a personal failing of Eeckhout. His work reminds me of Case and Deaton's Deaths of Despair. Both skilfully document how capitalism is failing the American people but then assert that the system can be redeemed by technocratic fixes whilst showing little curiosity about systemic change: Eeckhout says that "only pro-market capitalism can attain healthy competition" without even considering market socialism. Both are remarkably optimistic about the potential to reform capitalism whilst unable to conceive of more radical alternatives to the system.

In fairness, he's not wholly blind to the problem here. He acknowledges that such a call is "very idealistic" given that market power buys political power via paid lobbyists. But this misses the point that capital has many other sources of influence over government. There's simple deference; Gordon Brown's kowtowing to bosses was not motivated by personal greed. There's the belief (which as Eeckhout shows is sometimes dubious) that high profits are necessary to create jobs. There's simple ideology, which politicians have internalized. And of course, there is the influence of the media.

Reigning in monopoly power requires governments to overcome these forces. And that in turn requires the growth of either a threat to capitalism itself or at least a countervailing power to capital. It's no accident that capitalism was more equal (and productive) when there were strong trades unions and a threat of communism.

So yes, I think we do need intellectual (and social and economic) history - because it teaches us that meaningful improvements in economic policy must be a collective effort and not merely clever people proposing technocratic tweaks.

December 1, 2022

It's not about the money

One common mistake non-economists make when thinking about economics is that they think about money when money is often not the issue.

I suspect people appreciate this implicitly in their everyday life. The ��50 you spend in a record shop matters because it is ��50 you then don't have to spend on dinner with your partner. What you are giving up when you buy those records is something real - a date night.

It's in this context that higher energy bills are so nasty. The higher cost of gas means that even those of us who are quite well off must forgo something real, something nice - nights out, books or music. That hurts. And not just us personally. What's going on is a transfer of resources from dynamic, entrepreneurial sectors of the economy towards rentiers. As David Ricardo pointed out 200 years ago, that's the sort of thing that can push an economy into long-term stagnation.

Money, then, is in many contexts not the point. What matters are real resources and opportunities - the good things we must sacrifice to get other things. Money is just one measure of such sacrifices. But it is just that - a measure.

And not the only one. As I approached retirement, I thought of big-ticket items in terms of how much longer I'd have to work if I bought them: a car was a year's work, a holiday a month's work and so on. A labour theory of value makes sense because labour - leisure foregone - is a measure of what we must give up to get stuff.

All this might seem obvious, but it is often forgotten in politics.

For example, Mark Harper says it is "unaffordable" to give public sector workers pay rises that match inflation. "I do not have a bottomless pit of taxpayers��� money" he said.

But money is not the issue: governments can print limitless amounts of the stuff. What Harper should have said is that higher gas prices mean that the UK has become poorer: as a nation, our real income has fallen. Which poses the question: why should public sector workers not share in this fall?

Of course, you might well have a good answer to this: many have suffered years of falling real incomes, and there are others who should bear the cost instead.

And that's the point. Harper was using a nonsense claim about money to disguise what is a profoundly political choice, of who should suffer from our country's impoverishment.

It's not just Tories who talk of money when they should speak instead of real resources. Lisa Nandy has said that "the big problem is that there isn't enough money."

She is of course wrong to say there isn't enough money. But she is bang right to say there is a big problem. We lack real resources. Anyone wanting a big increase in public spending must answer the question not "where will the money come from?" but "where will the workers come from?" We are closer to full employment than we have been for many years, and there are certainly very few unemployed doctors or nurses. The government can print money, but it cannot print workers.

This is a big reason why the Truss-Kwarteng budget was such a disaster. The gilt market feared that tax cuts at a time of near-full employment would lead not so much to higher employment and output but simply to higher inflation.

It's in this context that Sunak and Johnson's health and social care levy made sense. We don't need higher NICs to finance public spending; printing money can do that. We need them to release labour that is otherwise unavailable when employment is so high. We need to reduce consumer spending so that retail and hospitality workers lose their jobs and become care workers instead.

Which poses a problem for the left. If we want more builders, home insulators, solar panel makers, care workers and NHS staff where will we find them?

Immigration, of course, must be part of the answer. Another part of the answer is that Labour might well take office when unemployment is higher than it is now, and so these workers can be taken from dole queues without raising inflation.

But what if these answers are insufficient? Then we might need higher taxes to force capital and labour to move from parts of the private sector to healthcare, greening the economy and building houses.

Not all taxes, however, would do this. Wealth and windfall taxes could in principle raise billions. But if these billions would otherwise be merely hoarded in bank accounts real economic activity does not decline and so there will be no release of capital or labour and thus no more potential housebuilders or nurses. The nasty fact is that if we want more health workers or more people working to decarbonize the economy then we need the sort of taxes that depress economic activity elsewhere - that is, taxes that don't just fall upon the mega-rich. The left needs to be honest here.

There's another sense in which some on the left are ducking a tough question - nationalization.

They are, of course, correct to say that money is no obstacle to this: it's quite sensible to borrow at a real interest rate of around 1% to buy a higher-yielding asset. But my question arises again: how does nationalization affect real resources? There's no question that the railways and Royal Mail are atrociously managed. But will nationalization change this? Yes, if bad management is due to bad incentives which public ownership could correct. But it does not if the problem is simply a lack of management ability. Nationalization is not an end in itself, but a means to an end. And we need to think more about those means and those ends.

My point here should also shape how we think about fiscal rules. High government borrowing becomes a problem when it deprives the private sector of real resources - either by creating a tight labour market or by raising real interest rates.

Clearly, neither is a problem at times of deficient demand of the sort we saw after the financial crisis. So fiscal rules should not constrain borrowing then. But when should they?

The answer depends in part upon the extent to which government borrowing raises interest rates, and also upon how much those higher rates depress healthy investment. If they deter firms from making emissions savings or productivity enhancements then government borrowing should be reduced. If instead they deter crypto-mining or property speculation, then high government borrowing is not so troubling. Personally, I don't think we can generalize on this point.

But there's another issue here: what sort of economy do we want? Do we want private affluence and public squalor (to use Galbraith's phrase) or something closer to the opposite? This is fundamentally and unavoidably a political choice. Talk of fiscal rules often effaces this fact in favour of arid technocracy.

And that's the point. We must think of economic policy in terms of real resources, not money. Whilst the question of how many unemployed resources there are must be a purely empirical one uncoloured by ideology or wishful thinking, the question of how we want to employ those resources - in healthcare, housebuilding, decarbonizing or in private consumption - must always be a political one. Talk of money and finance can sometimes be a technocratic trick to distract us from this fact.

Chris Dillow's Blog

- Chris Dillow's profile

- 2 followers