Chris Dillow's Blog, page 5

May 26, 2023

Securonomics vs productivity

"Globalisation, as we once knew it, is dead" said Rachel Reeves this week. Which is a problem for anybody wanting a high-wage high-productivity economy.

I say so for a simple reason: globalization in the sense of faster world trade growth raises productivity.

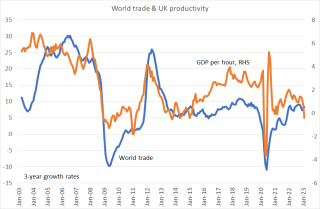

My chart shows the point, plotting three-year growth in world trade (as measured by the CPB) against UK productivity growth. It's clear that there's a correlation between the two. Of course, correlation is not causality. Some of the link is because the same things that depress one also depress the other - such as the financial crisis and the pandemic. But those events are not the whole story. The pre-crisis slowdown in world trade was associated with slower productivity growth; both grew weakly in the mid-10s; and both picked up in the late 10s.

In fact, we have strong reasons to think that faster world trade growth is indeed one cause of productivity growth (of many!). Productivity improvements ���seem to have been the effects of the division of labour��� wrote Adam Smith in the first sentence of the first book of modern economics. If you were to emulate Tom Good and try to become self-sufficient, you���d be poorer. What���s true of individuals is true of countries: just look at North Korea for an extreme example.

What's more, stronger world trade means greater competition. That encourages firms to increase efficiency or to innovate more, both of which raise productivity. It also means that managers visit customers and suppliers overseas and so can more easily learn tricks of the trade from best practice overseas.

Globalization doesn't just raise real incomes by raising productivity, though. It also does so by cutting prices thereby making people's wages go further. The deglobalization caused by Brexit, for example, has greatly added (pdf) to UK food bills.

If globalization is dead, therefore, we face a big obstacle to raising productivity and real wages. Which makes it all the more important to look for other methods of doing so.

But, but, but. Reeves is right to say that globalization had a downside: "whole industries were allowed to decline or disappear."

This, however, is what productivity growth is. Productivity does not rise because we become better at doing the jobs we are doing. It does so because low-productivity jobs disappear and are replaced by higher-productivity ones.

A famous paper by Jonathan Haskel and colleagues showed this (pdf). They estimate that during Thatcher's great shake-up of manufacturing "between 1980 and 1992 single establishment firms experienced no productivity growth among survivors." Instead, all the substantial growth there was came because inefficient firms closed, more efficient ones opened, and because big companies shifted output from their less efficient sites to more efficient ones. A similar thing, Haskel has found (pdf), is true in retailing: most productivity growth is due to the closure of old stores and opening of new ones, rather than to incumbents upping their game.

Growth, as Schumpeter said, is a process of creative destruction.

Which means there is a tension between Reeves' two objectives. An economy of high productivity growth is one in which there will be insecurity as low-productivity jobs will be in danger of being destroyed.

Policy-makers can in principle ameliorate this trade-off by having a more generous welfare state to support those whose jobs are destroyed and more active labour market policies to help the unemployed into those better jobs. (Yes, I mean help, not bullying). But Reeves' speech gave no hint of thinking along these lines.

Instead, she emphasises the upside of better jobs:

That means cyber amongst the former coal and steel communities of South Wales, robotics and AI in business hubs in Lancashire���s mill-towns and carbon capture and storage technologies pioneered and applied in the manufacturing landscape of Teesside.

But this still leaves the problem of job destruction. If these good jobs are created, people will move into them from low-wage work. Who then will do those jobs - the care work, the cleaning, the shelf-stacking?

This wouldn't be a problem if we had lots of unemployment or if Labour were endorsing high immigration. But neither is the case: Labour "want and expect net immigration to reduce."

Nor would it be a problem if the low-wage jobs were ones that we didn't want. But this is not so. "Skill" is an ideological construct: fund managers are considered skilled whilst care-workers are not. The "vibrant market" that Reeves wants might therefore move workers away from jobs that need doing.

Of course, the solution to this is to pay care workers more. But the taxes needed to do this will depress aggregate demand and so destroy other jobs.

But not necessarily the right ones. The jobs that need destroying are the bullshit jobs described by David Graeber; the producers of environmental, intellectual and risk pollution; DWP and Border Force staff who harrass benefit claimants and migrants; or those in the bloated financial sector. Job destruction, as I've argued, is not a task which can be left to the market.

It is, however, a question which Reeves is avoiding. Not only is she failing to see that "securonomics" and productivity growth are in tension, but she's not seeing that there must be losers from any serious attempts to raise economic growth - not just employers of low-wage workers, but also financiers and monopolists.

Yes, Reeves is breaking with New Labour in some respects, some of them welcome. But she's also continuing with them in at least one aspect - in not seeing that there are trade-offs and big conflicts of interest in economic policy-making.

Another thing: I'm also wary of Reeves' implicit assumption that we'll create lots of dynamic businesses if only we gave them easier access to finance. Whilst lack of finance is perhaps ones constraint on some firms, I suspect there are much bigger reasons for a lack of investment and entrepreneurship. But that's another story.

May 23, 2023

No magic money trees

John Rentoul has been mocked for claiming that "the Twitter consensus is that the magic money tree should pay to upgrade our sewage system". Such mockery is right; people think that water company owners should foot the bill. But John is dead right to alert us to the fact that, often, there are indeed no magic money trees.

His argument applies to privatizations. There is often no magic money tree that makes things more affordable in the private than public sector - as we see in water companies plans to make customers pay the costs of investing in the sewage system.

But that's just one example of a general pattern. The public-private partnerships and private finance initiatives, which New Labour greatly expanded, kept public debt off the books by promising companies who built schools and hospitals big cashflows for many years. But these proved more expensive for tax-payers than ordinary government borrowing would have been, which was why Philip Hammond scrapped them in 2018.

The idea that there was a magic money tree the state could shake to finance schools and hospitals has been refuted. And there was, at bottom, a simple reason for this. Governments can borrow more cheaply than the private sector. Shifting debt from the public to the private sector thus increases borrowing costs. And given that companies are less able to bear high debt than governments - because they can't print their own money or raise tax - it also increases financial fragility, as we saw with the collapse of Carillion.

Another example of what I mean are pensions. It's sometimes said that the pensions triple lock is unaffordable. It's not. If it stays in place, state spending on pensioner benefits will rise from 5.9% of GDP now to just under 8% in 2057-8. This is much less than many European governments - such as in Germany, France Austria or Italy - spend on pensions today.

What's more to my point, though, is that if we don't provide for an income in our old age via the state will we have to do so privately. And it's here that there's no magic money tree. Private pension fund managers charge big fees which compound hugely over time, and they entail big investment risk and longevity risk - risks which the state is better able to carry.

Health care is another example of what I mean. Long NHS waiting lists are forcing people to go private. What people save in taxes by not funding the NHS is thus, for many, offset by paying for private care. Austerity - back door privatization - therefore does not always save money; it merely shifts the cost from the healthy to the ill. Again, there's no magic money tree.

The same applies to talk of reforming the NHS. Of course, the NHS is inefficient, but that's just another way of saying it is a large organization. But the same things that cause it to be inefficient - lack of management skill, vested interests, whatever - also make reform so damned hard. The last major efforts at reforming the system - the introduction of internal markets and Lansley's reforms - were so ineffective they were subsequently reversed. The idea that reform is a magic money tree which can substitute for increased spending is optimistic.

"There's no magic money tree" is usually used as an argument against extra state spending. But it can just as often - and sometimes with more justification - be an argument against privatization.

Now, there are two objections to this. One is that the Treasury's short-termism and failure to see that balance sheets have two sides puts a block upon public sector investment. Privatization gets round this and so is in effect a money tree, a way of releasing investment. This is why Blair and Brown greatly increased private finance initiatives. It's also why privatization began in earnest in 1984: Thatcher sold off BT to prevent big investment in the phone network from showing up in the government borrowing data.

We must not, however, mistake bureaucratic convention and groupthink for economic reality. The reality is that governments can borrow more cheaply than the private sector, and so escaping the maw of the Treasury adds to borrowing costs.

A second objection is that privatization might increase efficiency and so cut costs. But this only works if monopoly is replaced by competition. Which often hasn't been the case. Water charges are 4.3 times as high as they were when the industry was privatized, whilst electricity prices are 5.7 times as high: consumer prices generally are 2.3 times as high. There's little sign here of competition driving down prices.

My point here is simple. What stops us doing good things are lacks of real resources - of capital, labour, technology, materials and managerial skill. It is only if we can create or mobilize these that we can have more or better schools, hospitals, utilities or whatever. If you have a plan for doing this - and maybe some of Labour's proposals to reform the NHS do - then you have an intelligent policy. Otherwise, you are just wibbling about magic money trees. And this is as true of some rightists as of leftists.

May 16, 2023

What the people want

Years ago, before the Great Forgetting, economists knew that people's preferences often did not originate with themselves but were instead cultivated by producers themselves.

Inspired by Vance Packard's best-selling 1957 book, The Hidden Persuaders, J.K. Galbraith wrote:

Production fills only a void that it has itself created...That wants are in fact the fruit of production wll now be denied by few serious scholars...The even more direct link between production and wants is provided by the institutions of modern advertising and salesmanship. These cannto be reconciled with the notion of independently determined desires, for their central function is to create desires - to bring into being wants that previously did not exist. (The Affluent Society, p 132-3)

This, he wrote, brings into doubt the question of why we should satisfy those preferences:

The individual who urges the importance of production to satisfy these wants is precisely in the position of the onlooker who applauds the efforts of the squirrel to keep abreast of the wheel that is propelled by his own efforts...The fact that wants can be synthesised by advertising, catalysed by salesmanship and shaped by the discreet manipulations of the persuaders shows that they are not very urgent. A man who is hungry need never be told of his need for food. (p132,35)

Not that Galbraith's point was new. Aesop's fable of the fox and the grapes made precisely the point that our wants are shaped by what we believe to be available. As G.K. Chesterton said: "no man demands what he desires; each man demands what he fancies he can get" - a point developed in Jon Elster's superb book.

Nor are our wants shaped only by others' deliberate acts - as Aesop recognised. They are also determined by our peer group as Robert Frank has shown, or by our moods - unhappy people spend more and save less - or even by the weather; in the summer prices of houses with swimming pools and convertible cars are higher.

All of which has led psychologists to fear that what we want is a poor guide to what will make us happy. "People are systematically prone to make a variety of serious errors in the pursuit of happiness" says Daniel Haybron. And Christopher Hsee and Reid Hastie write:

People systematically fail to predict or choose what maximizes their happiness...These findings challenge a fundamental assumption that underlies popular support for consumer sovereignty...namely, the assumption that people are able to make choices in their own best interests.

This poses a question: might a similar thing be true in politics? Certainly, some of Galbraith's near-contemporaries thought so. Peter Bachrach and Morton Baratz argued (pdf) that one aspect of political power was that "some issues are organized into politics while others are organized out":

Of course power is exercised when A participates in the making of decisions that affect B. But power is also exercised when A devotes his energies to creating or reinforcing social and political values and institutional practices that limit the scope of the political process to public consideration of only those issues which are comparatively innocuous to A.

Brexit is an example of this. Before 2015, less than ten per cent of voters thought the EU was the most important political issue, whereas after 2016 half did so. This change was the product of political activity: the people we now call Brexiteers successfully agitated to organize Brexit into politics. The demand to leave the EU was catalysed by salesmanship and shaped by the not-so discreet manipulations of the persuaders.

Such activity might also explain the oft-noted paradox that hostility to immigration is (with some exceptions) greater in areas of low migration. It's because such hostility is manufactured, whilst those with actual lived experience of it can see it to be much less worrisome.

We might be seeing the same thing now. Politicians tell us it is possible to "stop the boats" but don't tell us it's possible to have economic democracy. Is it a surprise, therefore, that voters want one but not the other? It wouldn't be to Aesop, Chesterton, Galbraith or Elster.

In fact, we have stronger reasons to question political preferences than consumer ones. In our everyday shopping we at least sometimes learn from experience whereas in politics this is harder because political issues are sometimes new, and certainly arise in different contexts. Yes some regret voting for Brexit, but - unlike consumer goods - you can't take it back to the shop. And, of course, if we buy shoddy goods we lose money ourselves whereas with a bad vote the costs are spread across everybody, thus diluting our incentives to think carefully.

What's more, there's a powerful emergent process which shapes political preferences - that of adaptation. As Amartya Sen put it:

The deprived people tend to come to terms with their deprivation because of the sheer necessity of survival, and they may, as a result, lack the courage to demand any radical change, and may even adjust their desires and expectations to what they unambitiously see as feasible (Development as Freedom, p62-63)

Kris-Stella Trump has shown how this is true of inequality: the higher is inequality, she shows, the more likely people are to regard greater equality as legitimate. A plan to cut the post-tax incomes of the richest 1% by, say, one-third would seem very radical today - even though it would leave them better off relative to the rest of us than they were in the mid-80s. Such resignation to inequality means there is less demand for redistribution, even without any work by the media.

The converse of this is also true. The rich get an over-inflated sense of entitlement and so their minor peeves - such as not getting the precise type of Brexit they imagine in their fevered dreams - come to dominate political discourse.

So, yes, Galbraith's point does apply to politics. Why then should we make a fetish of what the public wants? Suella Braverman says "the British people want us to stop the boats". But why is this a reason for doing so?

For some thinkers, it's not. Daniel Hausman has argued that it is only rarely the case that there is a good ethical reason to satisfy preferences, and thinkers such as Byan Caplan and Jason Brennan have argued for restricting democracy.

Such a view isn't as radical as it seems. When Margaret Thatcher described referenda as "a device of dictators and demagogues" she was (deliberately) echoing Clement Attlee and Roy Jenkins. Parliamentary sovereignty is a different thing from popular sovereignty.

Thatcher, like her contemporaries in all parties, thought the job of politicians was not so much to sheepishly follow public opinion as to shape it. In her 1975 speech opposing the EU referendum, she approvingly cited a letter to the Evening Standard pointing out that if it had been left to the will of the people. "we would have no Race Relations Act, immigration would have been stopped, abortions would still be illegal and hanging still be in force."

But why have politicians lost that conception of politics and replaced it with the "customer is king" approach?

The mere fact that they seem unaware of these contrasting positions is itself confirmation of Bachrach and Baratz's point, that some questions are excluded from politics.

One possible answer is that we are indeed living in the dystopia described by Alasdair MacIntyre at the start of After Virtue: we've lost the ability to reason about moral and political issues because all we have are fragments of different, contradictory frameworks and traditions.

But there's another possibility. It lies in the fact that our political system is failing. Politicians are regarded with contempt, not least because they have no coherent answers to the failures of British capitalism. In light of this, "parliamentary sovereignty" has lost its appeal. Why not, then, invoke the will of the people?

But of course, the likes of Braverman are selective in their love of this will, being much keener to cut migration than to tax the rich or nationalize utilities. That's of course no surprise: the Tory party exists to support inequality and the status quo. What should concern us is that the Labour party also does so.

May 5, 2023

Why not celebrate full employment?

To someone of my generation, there's a curiosity about politics today - that the Tories are not making more of the fact that unemployment is remarkably low.

Two facts make this especially strange.

One is that the government has bugger all else to celebrate. As Henry Hill, a Tory sympathizer, says "the Government���s list of achievements is thin." NHS waiting lists are at a record high; real wages have stagnated for 15 years; shit is pouring into our rivers and seas; housing is unaffordable and sometimes uninhabitable; record numbers of people are dependent on food banks; and our poorest citizens are becoming poorer than those of Slovenia or Poland. Given this litany of abject shame, why not highlight the one area where the UK is doing well?

And near-full employment is indeed something to celebrate. Joblessness causes misery and crime (pdf), and can leave lifelong financial and emotional scars. As David Bell and David Blanchflower wrote (pdf):

Increases in the unemployment rate lower the happiness of everyone, not just the unemployed...Unemployment increases susceptibility to malnutrition, illness, mental stress, and loss of self-esteem, leading to depression.

Which was why, for so long, full employment was considered the prime goal of governments. Back when policy-making was influenced by men of intellect William Beveridge wrote (pdf) that being without work was a "personal catastrophe." "Idleness even on an income corrupts; the feeling of not being wanted demoralizes."

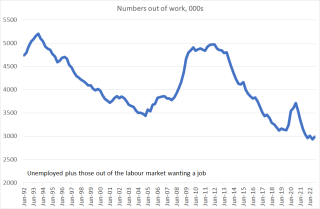

This isn't to say that one of Beveridge's "five giants" - idleness - is completely slain. Although the official unemployment rate is close to its lowest level since 1974 - a remarkable achievement given the nasty terms of trade shock that is high gas prices - there are still almost 1.8 million people out of the labour force who would like a job.

Nevertheless, the total out of work, at just under three million, is near a multi-decade low, and lower than anything reached under the New Labour government - although there are still more people under-employed now than there were for much of the 1997-2010 period.

Of course, it's not at all clear how far this is due to actual government policy. But there's no reason why this should stop the Tories claiming credit for it. A party that blamed Labour for the global financial crisis doesn't scruple about attributing economic outcomes.

Hence my puzzle: why are the Tories so quiet about this?

It could be that their silence is another symptom of their intellectual decline: they have lost the ability to think about economics. But I think something else might also be at work.

Of course, there would be an irony in the party of Thatcher - who denied that governments should have full employment as an objective - celebrating our proximity to its achievement. But the Tories have repudiated Thatcherism in other ways - in leaving the single market; in having the highest tax burden in 70 years; and in having a Prime Minister who wanted to "fuck business". So why not break with her in another way?

You might think it's because there is in fact little to celebrate. Many of the jobs created are low-productivity, low-paid and insecure ones.

In theory, however, full employment should be the solution to this problem.

For one thing, it should boost productivity as companies seek to replace scarce labour. Beveridge applauded "the stimulus to technical advance that is given by shortage of labour":

Where men are few, machines are used to save men for what men alone can do. Where labour is cheap it is often wasted in brainless, unassisted toil.

And for another, a sellers' market for labour-power should increase workers' bargaining power and hence, eventually, real wages.

Which brings us to the issue. There's little sign of either of these mechanisms working right now. The volume of business investment is still lower than it was in 2016. And real wages have actually fallen 2.1 per cent in the last 12 months.

This raises two dangers, one for all of us and one for the right.

The danger for all of us is perhaps that decades of abundant labour has caused bosses to lose the ability to replace labour with capital or to improve efficiency by any means other than brute coercion. If so, then it will be even harder than we think to raise productivity growth.

The danger for the Tories, though, is that workers won't always remain quiescent. We see their fear not only in their hostility to striking workers but also in Huw Pill's assertion that workers "need to accept" that they are worse off and stop bidding up wages*. What Beveridge saw as a benefit of full employment is for them a threat. As Kalecki famously wrote (pdf):

It is true that profits would be higher under a regime of full employment than they are on the average under laisser-faire; and even the rise in wage rates resulting from the stronger bargaining power of the workers is less likely to reduce profits than to increase prices, and thus affects adversely only the rentier interests. But "discipline in the factories" and "political stability" are more appreciated by the business leaders than profits. Their class instinct tells them that lasting full employment is unsound from their point of view and that unemployment is an integral part of the " normal " capitalist system.

Yes, unemployment poses challenges for the left. But it's a bigger problem for the right.

* Pedants might point out that Pill is a Bank of England economist and not a Tory. But as Arnaud Amalric said: "Caedite eos. Novit enim Dominus qui sunt eius."

April 21, 2023

Devaluing excellence

Disputes about wages are rarely about financial considerations alone, but are often tied up with ideas of respect, expectations and morality. The fact that we call wages "earnings" alerts us to the close link between pay and our sense of desert. As Daniel Kahneman, Jack Knetsch and Richard Thaler wrote in a famous paper (pdf), "rules of fairness can also have significant economic effects."

We should regard the pay disputes of academics and junior doctors in this light.

The thing is that they all did what teachers tell us are the right things to do. They studied hard and got top grades. And their reward? For junior doctors, it's a mere ��14 an hour (pdf). And many academics cannot afford (pdf) basic necessities and face job insecurity.

Yes, some will become well-paid senior doctors and professors (although even the latter have seen pension cuts). But their landlords won't accept the promise of big money in future instead of payment now, so why should they?

Hence their sense of injustice - a sense heightened by the contrasts between doctors' pay and the millions handed to firms' for often-defective PPE, and between academics' pay and that of vice-chancellors.

What we pay is what we value, and these priorities signal that the Tories value cronyism and managerialism more than learning.

From this perspective, we should regard the underpayment of junior doctors and academics alongside cuts to arts funding and the BBC's attacks on the BBC Singers and orchestras. (Yes, redunancies have been suspended, but the mere initial announcement of them indicated the BBC's priorities.) What all these have in common is an undervaluing of academic and technical excellence and an overvaluing of cronyism - not just in PPE contracts but in the BBC appointing Tories such as Robbie Gibb, Richard Sharp and John McAndrew to senior positions.

Here. as so often, we need Alasdair MacIntyre. He distinguished between goods of excellence - which consisted in mastery of particular practices - and goods of effectiveness: wealth, power and fame. Sometimes these two goods go together: if you are an excellent footballer, you'll acquire the goods of effectiveness. But often they don't, as when musicians struggle to earn a living.

The word "neoliberalism" is much misused. We might, however, attach that label to the valorization of the goods of effectiveness over those of excellence - of winning at all costs over performing well. This is true not just in the NHS, the BBC or universities. Barney Ronay's observation that the Chelsea team shows the "distorting effects of money without sense or love or care" is a complaint that the goods of effectiveness have eclipsed those of excellence. It's also a trend in both business and the public sector generally, where managerialism is eroding professional skill and autonomy; a big reason why many erstwhile "middle-class" people voted Labour in 2019 was that they have become proletarianized.

The intellectual decline of the Tory party is part of this trend. When MPs such as Dorries, Gullis or Anderson flaunt their boorish ignorance like pigs wallowing in muck they are demonstrating the same contempt for learning that causes them to underpay well-qualified professionals. Not that the disease is confined to a few grotesque outliers. Even the "sensible technocrats" such as Sunak or Hunt never give any hint of being influenced by serious thinkers in the way that Thatcher often expressed her debt to Hayek, Popper or Friedman. Matt Goodwin, emboldened perhaps by the knowledge that in the land of the blind the one-eyed man is king, has espied a gap in the market for a Tory intellectual - but his sneer that anyone demonstrating a sign of education is a member of the "liberal elite" merely further reveals the party's philistinism.

Which, from a historic perspective, is odd. Many Tories traditionally aligned themselves with an educated elite. Think of Edmund Burke fearing that, in a revolution, "learning will be cast into the mire and trodden down under the hoofs of a swinish multitude." Or Michael Oakeshott's claim that education is "an initiation into a civilization". Or Roger Scruton's defences of "high culture" against the depredations of the left. Or Allan Bloom's defence of the "canon" against the "closing of the American mind".

That the right has, perhaps with the sole exception of Jesse Norman, abandoned this tradition shows just how far it has been taken over by an obsession with money and power to the exclusion of excellence.

It's not just its crass philistinism that should trouble us about this. Everyone with a stake in currently-existing capitalism should be worried.

Intelligent defenders of capitalism have long known that its stability requires a large and contented middle class. Thatcher tried to create a property-owning democracy for just this reason. Which is just what her epigones are not doing. In alienating professionals such as junior doctors and academics (and squeezing them out of property ownership) they are creating a narrow elite to which erstwhile allies are now hostile. If doctors - a traditionally conservative bunch - won't side with the ruling class, then who will?

History has a warning here. Peter Turchin has shown that revolutions are more likely when the ruling elite becomes narrow, closed and antagonistic to the middle-class: think of the French and Russian revolutions.

Which is why everyone wanting capitalism to be sustained must support academics and doctors - not just because doing so valorizes intellectual achievement, but because it forestalls a dangerous isolation of the ruling elite. Sometimes capitalism needs an inoculation - a small illness to prevent a worse one.

You might think it odd that a Marxist is making this point. Well, whilst my brain and heart favour revolution, my Isa statements do not. As Hayek said (pdf):

The main task of those who believe in the basic principles of capitalism must frequently be to defend this system against the capitalists.

Of course I appreciate that some conservatives don't want to support "woke" academics, just as some leftists won't like seeing that there's a conservative case for higher pay in the public sector. But politics, if it is to be a worthwhile activity, must not be a search for ideological purity but rather a building of alliances.

April 15, 2023

When clever people do stupid things

Simon Wren Lewis asks:

There is no doubt that Lawson was far better qualified than many other Chancellors, and also that he was clever, so why did he get these major judgements wrong?

It's a good question because it broadens. Clever people gave us the poll tax, the invasion of Iraq, financial crisis and collapses of Silicon Valley and Credit Suisse.

So why do they so often get it wrong. There are many reasons.

One, which Simon attributes to Lawson, is arrogance. In ignoring his advisors, Lawson did not go as far as Kwasi Kwarteng (double first, PhD and Browne medal) who sacked one of his. And observers agree that one of the defining features of Fred Goodwin which contributed to the collapse of RBS was his arrogance. Being clever tempts men to ignore Burke's advice:

We are afraid to put men to live and trade each on his own private stock of reason; because we suspect that this stock in each man is small, and that the individuals would do better to avail themselves of the general bank and capital of nations and of ages.

Instead, they are prone to what Daniel Kahneman has called an illusion of skill. They believe their intellect equips them to foresee or control events which are largely unpredictable and uncontrollable in a complex world.

We see this in finance. Although intelligent investors do perform slightly better than others, they still make errors - such as buying expensive but poorly-performing funds - because they think they have the ability to spot good assets.

Closely related to arrogance is the failure to see that intellectual ability is often context-specific, that there are no general purpose experts. They forget Charlie Munger's advice: "one skill is knowing the edge of your own competency." Many men have made fools of themselves by spouting off outside their field of expertise: think of William Shockley, Bobby, Fischer, James Watson or Richard Dawkins...

Failing to know one's limitations isn't the only way intelligent people go wrong, as the story of Vicky Pryce shows. She went to prison because her great intellect was eclipsed by her hatred for her ex-husband. Which is a dramatic exemplar of a widespread tendency, for our intellect to fail us in times of stress. The better financial advisors tell people to never take decisions when we are emotionally aroused because this clouds our judgment and so "produces substantial financial costs".

Warren Buffett has famously warned of this. "Investing is not a game where the guy with the 160 IQ beats the guy with a 130 IQ" he has said. "You don���t need a lot of brains to be in this business...What you do need is emotional stability."

The ancient Greeks had a good word - phronesis, which referred not to mere intellect, but to the ability to apply that intellect appropriately in the right context. You all know clever people who lack that skill.

One reason they lack it is that intellect is not the same as biasfreeness. In Human Inference, one of the earliest books in the cognitive bias literature, Richard Nisbett and Lee Ross wrote:

There is no inferential error that can be demonstrated with untrained undergraduates that cannot also be demonstrated in somewhat more subtle form in the highlt trained scientist.

And David Robson has written that "greater education and expertise can often amplify our mistakes while rendering us blind to our biases."

One such bias is groupthink. In The Blunders of our Governments Anthony King and Ivor Crewe say this was true of the emergence of the poll tax. The people charged with reviewing local government finance were very bright - William Waldegrave was a fellow of All Souls - but they also, say Crewe and King, "developed a considerable esprit de corps". And this can drain any group of self-criticism:

Some of the best and brightest in British government - none of those intimately involved was remotely a fool - nevertheless contrived to produce one of the worst and stupidest pieces of legislation in modern British history.

But we don't need groups to turn smart people into bad decision-makers. We can do it on our own. There is, for example, no link between intelligence and the myside bias. In fact, greater intelligence makes us more able to see the flaws in opposing ideas and more able to defend our own with sophistry. It's perhaps for this reason that George Orwell said that "some ideas are so stupid that only intellectuals believe them."

What he's getting at here is ideology. Of course, we all have ideology - yes, even (especially) "moderate" and "reasonable" centrists. What we must not do, though, is let our ideology distort our assessment of the facts. This is what Lawson and Kwarteng failed to do: the ideology that tax cuts would swiftly boost potential supply led them to underestimate the impact they would have on inflation, inflation expectations and interest rates. Similarly, proponents of the poll tax let the ideological view that users should pay for public services colour their judgment about the feasibility of that tax.

It's not just partisan ideology that can hinder our intellect. So too does professional deformation, the tendency of our professional training to distort our perceptions. Academics, for example, might be antipathetic to my point here because they are apt to overweight the importance of intellectual ability. In the same way, engineers to often see everything as a control problem; lawyers over-estimate the role of law in social change and - yes - economists can exaggerate the importance of incentives.

The same applies to politicians. Even the very smartest of them, merely by virtue of being politicians, will be biased. They are disproportionately likely to be over-optimistic about the ability of good policy to improve things; to exaggerate the competence and knowledge of top-down controllers (which contributed to the Iraq disaster); to under-play the value of emergence and freedom; and to overvalue hard work.

Raw intellect, then, is on its own useless and sometimes downright dangerous.

This is not to say decision-makers should be chosen for their stupidity: if this were so, we would now be living in a golden age of governance. What it is is an argument against epistocracy.

It's also an argument for ensuring that intellect exists not in individual brains but in institutions and habits. Except for a little seasonal investing, my investments are all passive: I merely make a regular monthly payment into tracker funds. I do this because good habits matter more than thinking about investing with all its pitfalls. The same should be true in companies. The best ones have organizational capital, routines which help limited people do good things. Well-functioning markets also do this, by weeding out egregiously incompetent companies. And the same could be true in politics: deliberative democracy could in principle mobilize the general bank and capital of wisdom.

But of course, our actually-existing institutions are far from ideal. The marketplace of ideas - of which the media is a big part - selects against good ideas and in favour of bad. Economic policy is bad not (just) because politicians are stupid but because there are powerful pressures from the forces of conservatism operating against good policy. Companies sometimes select in favour of psychopaths (pdf) and the overconfident. Academics produce bad research not because they are stupid but because of the compulsion to "public or perish." And the financial crisis was caused in part by bad incentives: bankers were paid well to ignore risks.

Which brings me to my point. We must avoid the schoolteacher attitude to politics and business, marking the work of politicians and businessmen as if it were a test of intellectual ability and singling out the best and worst students. Instead, we must consider institutions. Do we have those institutions which help filter out incompetence and bias, or which are resilient to error? The answer, for now, is: no.

April 1, 2023

Why not raise CGT?

The Labour party is more influenced by the Tory press than by economic rationality. That's the inference to draw from Rachel Reeves saying she has no plans to raise capital gains tax.

I say this because there is a widely-accepted economic logic for doing so. It is that income and capital gains are much the same: what should matter on any investment is the total return, not the form in which that return comes. Taxing capital gains at a lower rate than income therefore distorts individual behaviour. For assets held outside of tax shelters, this pushes investment towards shares that don't pay dividends - which are often spivvy Aim stocks - and away from dividend-paying ones. It encourages investors to sell some shares merely to realize a capital loss and to hold others to avoid a capital gains tax bill. It encourages people to take their returns as capital gains rather than as income, which often entails the deadweight costs of keeping armies of lawyers and accountants looking for tax fiddles. And it favours financial capital over human capital.

In all these ways, having a lower CGT than income tax rate is iniquitous and inefficient. This argument is separate from the question of whether or not we should tax the rich more.

Sensible economists have long appreciated this. "Capital gains need to be taxed at the same rate as other components of income" said the Mirrlees Review (pdf) in 2011. And back in 1988, Nigel Lawson said:

In principle, there is little economic difference between income and capital gains, and many people effectively have the option of choosing to a significant extent which to receive. And in so far as there is a difference, it is by no means clear why one should be taxed more heavily than the other. Taxing them at different rates distorts investment decisions and inevitably creates a major tax avoidance industry.

Why, then, is Reeves so loath to raise CGT? Doing so feeds into the impression that Labour lacks not just ideas, but any basis in serious thought.

The answer, I think, is simple. The Labour leadership is terrified of the headlines that would accompany even rational tax reforms: "tax raid on millions", "attack on business" and so on. As I've said, what matters in politics is not intellect, but power. Intellectually, there's a case for equalizing CGT and income tax rates. But intellect loses to power.

A sensible Labour party could however use the media to its own advantage here, at least once it is in office: it is always easier to get forgiveness than permission.

Another media attack upon Labour is that of fiscal profligacy: "where will the money come from?" Labour could answer this question by using CGT simply as a revenue-raiser.

Strictly speaking, of course, this makes little sense, and not just because the rise wouldn't raise very much. What a Labour government will need is not money but real resources: nurses, care-workers, builders, skilled management and so on. Raising CGT would tax cash that would largely be saved rather than spent, and so would do little to release these resources.

But we don't live in a polity in which good arguments prevail, not least because years of intellectual pollution from the media have replaced them with mindless drivel. The media would therefore have no right to complain if Labour were to raise CGT merely to "raise revenue". If you make bombs you don't win any sympathy if one goes off in your face.

March 30, 2023

Against schoolteacher politics

There's a common mistake in looking at politics which is shared by the left and right - to regard bad policy as mere intellectual error.

Here, for example, is Mike Denham of the TPA complaining that Jeremy Hunt "has not tackled the big problem" of "excessive public spending", as if the Chancellor were simply not just clever enough. What he fails to say is that such a high and rising share of public spending in GDP is not just the result of demographic forces and a lack of productivity growth in the NHS. There's something else - economic stagnation.

Some back-of-the-beermat calculations show the point. Since 2007 real GDP has grown by just 1% a year. Had it instead grown by 2% (which is still less than it did in the 40 years before then) the economy would be 16% bigger than it is. Which means that for the same level of government borrowing we could have ��100bn more public spending and still have lower shares of spending and taxes in GDP than we have now. Alternatively, with the same tax take, we could have eliminated the deficit and still had ��13bn higher public spending. Or, if you prefer, we could have the same deficit and a six percentage point lower share of spending in GDP, or five percentage point lower share of taxes.

In other words, "excessive" public spending is the product not (merely) of regrettable political choices but of weak growth. The share of public spending in GDP is driven much more by the state of the economy than it is by the will or ideology of governments. Had we had happier economic circumstances, it's highly likely than Denham's complaints would have less force.

But why have we have such weak growth? Here, we encounter another example of the mistake I have in mind: the financial crisis of 2007-08 is often attributed to bankers' bad decisions and/or the failure of regulators*.

What this misses is the point made (pdf) by Ravi Jagannathan and colleagues - that the crisis was "the symptom not the disease". High savings by fast-growing emerging economies such as China forced down western interest rates. In a better world, this would have financed a boom in useful capital spending, thereby increasing productive potential and real incomes. But it didn't because there was, as Ben Bernanke said in 2006, a ���dearth of domestic investment opportunities��� in the west. The upshot was therefore a boom in property speculation and a reach for yield that fuelled demand for mortgage derivatives. In this way, falling yields led not to greater wealth for all but to financial fragility and bust.

The crisis, therefore, was not (merely) the result of individuals making bad decisions. Yes, they did, but people make mistakes all the time; blaming the crisis on mistakes is like blaming a plane crash on gravity. Instead, it was the product of fundamental forces within capitalism.

Yet another example of what I have in mind is fiscal austerity. Countless economists have pointed out - correctly - that this is terrible economics (pdf). What this misses is why such a bad policy was selected for. The fact is that austerity served many interests - low interest rates suit financiers and rentiers - and the media, partly because it represents these interests, fails to scrutinize adequately such policies. Austerity wasn't just an intellectual failure, but an institutional one.

A further example lies in policies towards economic growth. Intellectually, these are trivial; most economists would agree upon half a dozen pro-growth policies even if they disagree about their weighting: planning reform; tax reform; rejoining the market; better competition policy; infrastructure investment; better vocational training; and so on. The absence of these policies, however, is not an intellectual error. It's because powerful vested interests would be opposed to them. Achieving pro-growth policies is a matter of power, not brains.

A final example is Peter Stefanovic, whose regular videos expose Tory dishonesty. The problem here is not that his work is wrong. It's not. It's that it begs the question: so what if the Tories lie? All informed Tory voters knew in 2019 that Boris Johnson was a serial liar. And they didn't care. Dishonesty is a path to power. In this context, the truth doesn't matter.

What's going on here is, I suspect, an example of how even good schools inculcate an ideology into us. We learn at school that if you are clever and honest you will get a reward or at least avoid punishment. And we carry this lesson with us even into domains where it is not true, such as politics. It might be no accident that the mistake I'm describing is often committed by academics. Take for example this from Case and Deaton:

If technological change and globalization have been responsible for hurting the working class, it is not because that is what technological change and globalization must do; it is because policy was neither wise nor imanginative. (Deaths of Despair p222).

They treat bad policy as if they were marking a bad student's essay. Which is professional deformation. Bad policy is not mere intellectual error. It is the product of capitalism - of economic stagnation and of how capital exercises power over the state. This is true whether you regard bad policy as "excessive" public spending, austerity or lax regulation.

My point here is that political analysis and change requires much more than intellect and knowing the truth. Politics is not merely a matter of asserting one's intellectual or moral superiority. It requires an analysis of capitalism: why it has delivered stagnation, and why it holds so much power over government.

You might think this is a Marxian claim. Well, not entirely. It's also Econ 101 - the idea that people, including politicians, respond to incentives. It is incentives that got us into this mess. And it is different incentives that will get us out of it.

* Regulatory failure is the kindergarten theory of economics: it regards bankers as being like unruly children who need constant close supervision. If such a theory is correct, it is hardly a defence of capitalism.

March 13, 2023

Technical regress

There's a fascinating TV series on now about modern social and economic history. I refer of course to the re-runs of Brookside on STV Player.

One thing this shows is how many opportunities there in the 80s were for workers to top up their wages by stealing from their employers, either by putting their hands in the till or by nicking stuff to sell to their friends. The closure of such opportunities thanks in part to technical change might help explain increased inequality and the Easterlin paradox, as I discussed here.

But there's something else. In one episode the post arrives at breakfast time. Today, this is unheard of. What a poverty-stricken city could achieve 40 years ago is now not possible even after decades of IT improvements. What we have here is technical regress.

Of course management of the Royal Mail and Post Office has long been indistinguishable from dogshit, but this regress is not confined to the postal system. The UK has lost the ability to build train lines. The BBC is less able (or willing) to make high-brow TV programmes whilst much of its current affairs output has become unwatchable. Water companies have become unable to maintain clean rivers. Construction productivity in the US has fallen since the 1970s. Academic research has deteriorated. And Cory Doctorow has described how platforms have become enshittified.

Lest this sound like an old man's nostalgia, I'll point to ONS data. These* show that there are many industries where gross value added per hour worker is lower now than it was in 2007, among them mining, pharmaceuticals, construction, water and wholesaling. In this sense, technical regress has been widespread.

All this alerts us to the fact that supply shocks are not just rises in the costs of raw materials due to wars. They can take the form of companies becoming less able to do things.

Some economists have long scoffed at this. Brad DeLong has called it the "great forgetting" theory of recessions. But I think there's something to be said for it.

For one thing, organizational capital is brittle; it can be destroyed by bad management, which is one reason why so many once-good companies get into trouble.

What's more, such declines and failures don't merely mean that capital and labour are swiftly redeployed at more efficient companies. Economies don't move seamlessly from one happy equilibrium to another. Instead, as Banerjee and Duflo point out in Good Economics for Hard Times, they are sticky: adjustments are slow, so technology shocks can lead merely to stagnation rather than to faster growth.

This is especially the case when, as Xavier Gabaix has shown (pdf), some companies are so big that their getting into trouble is itself a macroeconomic event, or if those companies are hubs, or key members of networks (pdf).

You can read the financial crisis as a form of technology shock - banks became less able to produce credit - and that had spillovers onto the general economy. Or the inability of TransPennine "Express" or Avanti West Coast to run trains has spillovers onto productivity generally as people can't get to work or meetings or are stressed out if they do. Or the failure of large department stores such as Debenhams leads to depressing high streets and shopping malls, causing less custom for other shops.

Now, you might reply here that a lot of these examples aren't so much of technical regress as of bosses degrading quality to get a bigger slice of the pie at the expense of workers or customers. In some cases, yes. But this merely reminds us that the production process is not merely a matter of solving constrained optimization problems as the neoclassical fairy tale says, but is also a location of class struggle.

All this should be troubling for mainstream economics. It means (some?) downturns are not merely fluctuations in demand which are ameliorable by monetary or fiscal policy but are instead the result of company- or industry-specific supply shocks. The fact that recessions have been almost all unpredicted is, I suspect, consistent with this.

This is not just an economic issue. It's a political one. Keynesian economics offered social democratic governments the possibility of controlling economic growth without having to interfere in capitalist management of workplaces. That option, however, exists only if recessionary threats come only from demand shocks and if productivity continues to grow thanks to capitalist dynamism.

Such conditions, however, are now absent. Which means we must take an interest in what Marx called "the hidden abode of production". We must take seriously the possibility that managerialism can no longer raise efficiency and that, as Michael Roberts says, there is a case for "giving workers democratic control of production and services and ending the autocracy of grotesquely overpaid chief executives and shareholder power."

This should not be so radical. Basic economics says that if a resource is scarce we should try to economize on it - and quality management is very scarce.

There is, of course, little evidence that the Labour party is thinking along these lines. Evidence-based policy-making has fallen out of fashion now that the evidence shows that capitalism isn't working.

* Yes, these. Suck it up, FT style guide.

March 6, 2023

Economic growth: who loses?

Labour's promise to "secure the highest sustained growth in the G7" is so far a mere aspiration without a detailed plan to achieve it. It is like a man claiming to want to become a great guitarist without practising or studying - and just as impressive and as likely to succeed.

The party promises to correct this omission in coming months. I would hope that one question it answers is: who is it going to hurt?

I say this simply because even mainstream policies to increase economic growth would undermine many vested interests and ideas. For example:

- Nimbys. Economic growth requires more liberal planning laws - be it to enable universities to build more laboratories, to get us more wind or solar farms, or of course to build more houses (which itself could raise productivity). That's going to hurt nimbys. Westlake and Bowman's idea for street votes on new developments might mitigate a lot of this hurt - by ensuring residents benefit from such developments - but it won't appease all the die-hard nimbys.

- Land-owners. Most economists, I suspect, agree that we need to tax businesses less and land-owners more: Westlake and Bowman, for example, advocate replacing business rates with a land tax. Whilst this would encourage business formation and expansion and help solve the problem of high streets being blighted by closed shops, it would of course hit commercial property owners.

- Financiers. Westlake and Bowman also advocate eliminating the tax deductibility of corporate interest payments to end the bias towards debt financing (and by implication the bias against equity finance). That'll hurt some lenders. So too would a state investment bank aimed at supporting start-ups, simply because it would create more competition. And of course, one effect of higher trend growth would be higher real interest rates - the two are correlated - which would raise the costs and dangers of all leveraged strategies.

- Monopolists. The UK has some of the highest energy costs in Europe, thanks to lax regulation of our privatized industries. This squeezes economic growth in exactly the way David Ricardo described 200 years ago; if we are spending all our money on economic rents, there's less to spend on other things and hence less revenue for genuine entrepreneurs. Pro-growth policies would therefore either cap energy prices or tax away the profits of energy companies.

- Incumbent companies. Economic growth requires fiercer competition, not least because productivity increases come not so much from existing firms upping their game but from new companies starting and efficient ones expanding. This in turn requires tougher competition law to help new start-ups or to break up large inefficent firms such as BT.

- Some workers and employers. We might be close to de facto full employment: the sum of the unemployed and those outside the labour force wanting a job is close to its lowest since records began in 1992*. This means that if Labour really wants to create significant numbers of good jobs in the green economy, care sector, housebuilding or wherever it will have to destroy some others. This of course is what "fiscal responsibility" means: cutting some spending or raising taxes to pay for other spending priorities means cutting jobs and businesses. The question is: which jobs and businesses does Labour wish to destroy? It shows no interest in this question.

- Brexiters. One of the few big, quick ways to raise growth would be to rejoin the single market. Which would of course outrage Brexiters and the right-wing media: liberalizing migration policy would have the same effect. The more intelligent of these might also oppose economic growth because they know that stagnation breeds reaction and illiberalism and so feeds their agenda.

Nothing I've said here is terribly left-wing. I'm not talking about radical pro-growth policies such as economic democracy, income redistribution or universal basic income but merely bog-standard orthodox economics. And yet even such mainstream policies would upset a lot of vested interests. Indeed, there's little evidence the voters want economic growth: they voted against it in 2010, 2015, 2016, 2017 and 2019.

Any serious economic policy must be aware of this opposition to growth, and be prepared for the fight.

The challenge here is not an intellectual one. Most economists roughly agree what type of policies we need to raise growth, even though we differ upon the relative importance we'd attach to them or to just how effective they'd be. But politics is not about intellect, and raising growth is not merely a technocratic exercise. Instead, it's about power. Would Labour have the power to face down anti-growth interests? Can it mobilize countervailing forces to them? If stronger growth is to be any more than an idle aspiration, it must be serious about these questions. A purely top-down managerialist ideology cannot be sufficient.

* That phrase de facto is important. Labour isn't wholly fungible, and there'll always be some unemployment simply because of mismatches between labour supply and demand. What matters is whether the unemployed have the skills or health to do the jobs Labour wants; it is improbable that people suffering from long covid will quickly be able to work on building sites, for example.

Chris Dillow's Blog

- Chris Dillow's profile

- 2 followers