Chris Dillow's Blog, page 7

November 16, 2022

In praise of conventional thinking

When does innovation work and when not? I'm prompted to ask by Ed Smith's wonderful new book, Making Decisions, which argues for the need for"anti-processes", original thinking and spontaneity to resist "the slide into bureaucratic inertia":

If your decisions do not diverge from conventional wisdom in any important respect, you are failing to do your job. Indeed, you no longer have a job. You have a sinecure.

All this is good and true. Following process and protocols can degenerate into groupthink, cargo-cult decision-making, and an irresponsible deference to algorithms.

But, but, but. I read Ed's book whilst cryptocurrencies were collapsing: whilst Elon Musk was ruining Twitter; whilst we are still awaiting the "sunny uplands" of Brexit; and a few weeks after Liz Truss's promise of "doing things differently" ended in abject failure. All of which show that there's something to be said for cleaving to the conventional wisdom. As Edmund Burke said:

We are afraid to put men to live and trade each on his own private stock of reason; because we suspect that this stock in each man is small, and that the individuals would do better to avail themselves of the general bank and capital of nations and of ages.

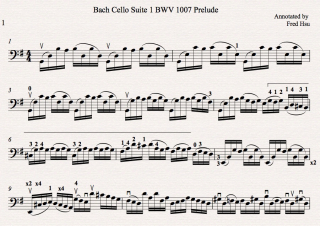

Reinforcing this point, whilst reading Ed I was listening to a lot of J.S. Bach, whose life shows that great genius sometimes consists not in originality but in sticking to rules.

Economics, perhaps, offers more examples of what I mean. It's not clear that recent new economic thinking - be it DSGE models or MMT - is much of an improvement on the functional finance and structural models we had before the 1980s. A while back, the Guardian used to run tiresome articles calling for new thinking about economics, when what I suspect they meant was a return to old thinking.

Nor is economics alone here. In Science Fictions, Stuart Ritchie describes "a deep corruption within science itself", which has a "dizzying array of incompetence, delusion, lies and self-deception." Hence the replication crisis which seems to have afflicted most academic disciplines. "New thinking" is often bad thinking with dubious results.

All of which raises the question: under what circumstances should we stick to conventional thinking, and which not?

Of course, the best time to innovate is when there is cheap money and lots of mug punters. The collapse of cryptocurrencies is yet another reminder that actually-existing markets incentivize bad innovation rather than good.

That aside, there are, I suspect, four conditions when we should reject Burke and Bach in favour of Smith.

One is that the conventional wisdom is sometimes merely the groupthink of the privileged, who use it to entrench inequality. Talk of a "fiscal black hole" for example is used to justify otherwise questionable austerity, just as talk of incentives or deregulation (pdf) can be a ideological cloak for inequality.

A second is that the cliche is true: necessity is the mother of invention. Bach had such abundant resources of genius that he could create brilliantly within existing conventions; he didn't need to innovate. The rest of us, though, often aren't so lucky. Francis Spufford's brilliant Backroom Boys describes how British boffins in the mid-20th century developed space rockets and computer games with little budget and puny computing power.

Ed had to do something similar. In 2019 England lacked top-quality opening batters and so experimented with a big hitter, Jason Roy, at the top of the order. That didn't work, but the subsequent performance of England's openers suggests it was worth a try.

A more successful example of innovation in response to lack of resources was "moneyball". The Oakland Athletics' small budget for players led their manager Billy Beane to evaluate players on the basis of statistics rather than conventional coaching judgements which led (briefly) to the recruitment of undervalued players and an improvement in the team.

Economic policy also provides an example. The UK adopted inflation targeting in 1992 in a panic and pretty much as a last resort after previous "monetary anchors" such as M3 targets, shadowing the Deutschemark or ERM membership had failed. Until recently, it worked much better than its predecessors.

A third circumstance favouring innovation and thinking outside the box is when the environment changes. Cricket provides another example. Jonathan Liew describes T20 as "an entirely different sport now" requiring the "shedding the decades of ingrained cultural baggage." In T20, a team's most aggressive batter should be not in the middle order but an opener, simply because he can then potentially face more balls.

The environment, of course, also includes technological possibilities. These don't just facilitate new companies, but also new strategies. As Stian Westlake and Jonathan Haskel have pointed out, modern intangible assets make production much more scalable which enables a few successful companies to get very big - hence the emergence of superstar (pdf) firms.

We see - or should see - this in politics too. The genius of Blair and Brown was to see that changing socio-economic conditions after the 1970s required a new form of social democracy. Equally, though, economic changes after the 90s requires yet another rethinking of social democratic politics. Most Blairites and Corbynites are too tribal to see it, but in important respects Corbyn was the heir to Blair.

But there is a limit here. It's easy to see a changed environment when in fact there is only fashion. One of the surest ways for investors to lose money is to believe "this time is different". Which it rarely is. Conventional thinking, such as intelligent momentum investing, beats believing hype about new technologies.

We could add a fourth circumstance when thinking outside the box works. In strategic interactions, be it sport or business, it can give one an edge over one's opponents. Arsene Wenger's use of healthy diets and more overseas players gave Arsenal big advantages in the late 90s.

The problem with these, however, is that one's opponents quickly learn to emulate such innovations, thereby neutralizing them. Wenger's use of sports science became less help as other coaches copied him, and Billy Beane's moneyball became less effective as rival teams adopted his methods.

The point generalizes. William Nordhaus has shown that the profits to companies' innovative activities are usually tiny simply because new products and processes get copied, thus bidding away initially high profits. Sustainable high profits come from conventional thinking about how to hold down costs, preserve brand power and fend off competitors thus maintaining what Warren Buffett calls economic moats.

All of which is to merely regurgitate an old saying of Niels Bohr: the opposite of a great truth is another great truth. Whilst there is sometimes (occasionally) a case for original thinking it is also true that conventional ideas are sometimes conventional for a very good reason. Which vindicates Ed's point: we will always need a "human dimension" if we are to have a hope of distinguishing the two.

November 4, 2022

The austerity choice

The Tories, aided by much of the media, are trying to pull a con trick. They want to present spending cuts as a technocratic necessity when they are in fact a political choice.

A big part of this trick is the idea that there is a fiscal "black hole" that needs to be plugged. Fiscal black holes, however, are not like stellar ones. They are not objective physical facts, but are subjective economist-made artefacts. This is partly because they are products of economic forecasts and any forecast, as Carsten Jung says, "depends hugely on the assumptions for economic growth, inflation and interest rates." But it's also because, as Ed Conway says, "they exist only relative to particular fiscal rules." If the fiscal rule mandates a large surplus, a given forecast deficit will imply a big "black hole" but if it permits a large deficit - voila - the black hole disappears.

For example, the IFS's Carl Emmerson says:

We need a credible plan to ensure that government debt can be expected to fall over the medium-term.

But this poses questions. Why must government debt be expected to fall? Why isn't mere stability sufficient, given that there is no credible evidence that a particular debt-GDP ratio leads to trouble? What does "medium-term" mean - two or three years, or five or ten? And should the requirement to cut debt be absolute, or instead contingent upon factors such as economic growth, inflation or bond yields?

The size - or even existence - of the "black hole" is therefore a choice. It depends upon the choices you make when you produce economic forecasts. And it depends upon your choice of fiscal rule. And fiscal rules, remember, are very much a political choice: since 2010 the government has changed (pdf) them in April 2011, March 2014, December 2014, October 2015, January 2017 and January 2022.

The only black hole that exists for sure in this debate is in the media, where political journalists are so dense that little can escape from them.

None of this, however, is to rule out some type of austerity. There might be a case for it. But if so, it is for a reason the Tories don't want to advertise.

Quite simply, it is because we are a poorer country than we would like to be, and if we are poorer we just can't afford stuff (yes, economics can be simple.)

One reason for this, of course, is that higher energy prices are cutting our real incomes. To the extent that these are temporary, there is a strong case for government borrowing to smooth out higher costs over several years. But it's not clear that this is wholly the case: although gas prices have fallen since the summer, they are still well above their pre-2022 levels.

But there are other causes of our low incomes. Some are policy choices, such as Brexit, antipathy to migrants and the failure to invest in infrastructure. Others, though, are the failures of the private sector that have given us 15 years of flatlining productivity. One symptom of this, as Duncan Weldon has pointed out, is that labour-intensive hand car washes have replaced automated ones.

And herein lies the fiscal policy problem. Our economy is so labour-intensive that we are near full employment - maybe not actually at it, but near it. There is therefore a real resource constraint upon fiscal policy: a loosening of fiscal policy will lead not so much to increased employment and output but to inflation - which is one reason why bond markets took fright at the Truss/Kwarteng Budget.

Herein lie not one but two different arguments for austerity.

Argument one is that tigher fiscal policy will cut aggregate demand and thus inflation, and so prevent interest rates rising as far as they otherwise would. Austerity, then, is the price to pay for lower mortgage rates.

This is a choice. Such a policy would benefit home-owners, and especially that minority that benefits from rising house prices, to the detriment of public service workers and users. Which poses the question. Why should wealthy people gain more at the expense of some of the most vulnerable such as those with serious health or educational needs? Talk of needing to fill a fiscal black hole effaces this question, and denies a key fact - that policy-making is about power, and choosing whom to throw under the bus.

Argument two is that when we are near full employment, fiscal austerity is necessary to release the real resources needed to work on our priorities. If we want more nurses, social care workers, home insulators or solar panel manufacturers we need to stop some people doing the jobs they are currently doing so they can transfer to these others. The question "where will the money come from?" has always been a bullshit question asked only by dickheads. But the question "where will the nurses come from?" most certainly is not.

Of course, in a rationally governed nation, part of this answer would be: from migrants. In the real world, however, the answer lies in tighter fiscal policy. This was the (largely unspoken) logic behind Sunak's health and social care levy: higher national insurance contributions would cut consumer spending, thereby forcing some retail, hospitality and nail bar workers out of their jobs, from where thry could find work in social care.

Which brings us to the problem. Neither left not right are making this argument. The right isn't justifying austerity on the basis that it's needed for a greener, caring economy. Nor, of course, can they, because such an economy requires higher public spending. And Labour are dodging the question. To a greater extent than other taxes, windfall and wealth taxes seize money that would otherwise be saved rather than spent. They therefore do little to depress demand and thus little to free up labour. Such taxes are vindictive (for me, a feature not a bug), but they are cargo cult fiscal policy - a worshipping of the fetish of "sound money" whilst failing to identify the fundamental question.

Which is: what kind of economy do we want? In a resource-constrained economy, we cannot have more private consumption, more people working to decarbonize and more social services. Nor even can we have adequate public services at current levels of taxation and economic growth.

We must choose. Carys Roberts is right: macroeconomic policy "isn���t simply a technocratic exercise to fill a 'black hole'. It���s deeply political."

Which is why talk of fiscal black holes is so nasty. Not only is it terrible economics, but it is also terrible politics in two ways. First, because it tries to pretend that politics is a merely technocratic recognition of necessity, thus effacing the fact that it is about choice. And second, because it denies the fact that years of economic dysfunction have left us with real and nasty choices.

October 19, 2022

The cost-cutting error

It's being said that the government is looking to cut costs. Such a framing is in many cases wrong and dangerous.

To take an example, in this clip the BBC's Jon Kay puts it to Jonathan Reynolds that "we can't afford [the pensions triple lock]; the economy can't afford it...so how are you going to afford it?"

The problem here is that cutting real-terms state pensions is not a saving. A lower state pension means that younger people must either save more privately for their old age or work longer (or both). Cutting the state pension therefore does not save money. It merely shifts the cost of provision for old age from the collective to individuals. To speak of the government cutting costs in this context is therefore plain wrong. It's not cutting costs, but merely shifting them.

The same applies to some other possible government cost savings. In scrimping on hospital provision the government has pushed NHS waiting lists up to record highs, one effect of which is to increase the number of people going for private treatment. Again, what's happening here is not that the government is cutting a cost, but that it is transferring it - from the state to those who can afford to go private.

An even more obvious example of what I mean are benefit cuts. These merely transfer costs from government to benefit recipients who must cut their spending and lead meaner lives.

The cost does not fall on them alone, however. It also falls upon those companies who suffer lower demand when benefit recipients cut spending. When Tesco chairman John Allan says we have "a moral responsibility" to look after people suffering from the cost of living crisis, he's appealing to the government to help his firm. Smarter capitalists know that austerity hurts them too.

In cases such as these, therefore, talk of the government cutting costs is plain wrong. What it is doing is shifting the costs, from the collective to individuals.

In this cases, the key question is: who is best able to bear costs - the state or individual?

In the case of pensions, I think the answer is clear - the state. Private pension provision is difficult and expensive. Not only do we face high fees from the organized theft that is the fund management industry, but we also face investment risk and longevity risk. The state is better on all three counts.

Similarly, scrimping on NHS spending introduces risk into our lives - that of being impoverished by ill-health. Benefit cuts have a similar effect, forcing individuals and retailers into being more exposed to bad economic times. They therefore weaken the automatic stabilizers that help protect us from recession.

In all three cases, the Tories are stepping back from a classic function of the state, which is to pool risks. It is transferring risk from government to individuals, who must take more investment risk, risk of impoverishment by ill-health, or risk of income loss in bad times. In this context asking "how great is the 'black hole' in the public finances?" is the wrong question. The question is: which costs and risks should be borne by the state and which by individuals?

This is not to say however that all possible government cuts are merely shifting costs.

One pure cost saving would be the reduction in the deadweight costs of administering taxes and benefits. Shifting taxes from incomes to land would be one such saving; land taxes don't have the disincentive effects that other taxes do. So too would simplifying the benefit system.

Other cost savings would be reducing the functions of the police, for example by legalizing drugs. Yet another would be cutting military spending: if you cut health spending, we might buy a private operation, but if you cut military spending we'll not buy our own private nuclear weapons. You can think of other examples.

You might reply that even in these cases, cutting government spending is not a pure cost saving as it entails job losses. Not necessarily. We are close to full employment, which means we must consider not only the volume of employment but the nature of it: do we really want arms manufacturers and a surveillance state rather than care workers and medical equipment?

Now, you might quibble with my individual judgments of particular cases. But I think the distinction I'm making between cost savings and cost transfers is robust and important. What we must ask is not whether the government needs to find savings, but other questions: what costs must be borne by the state and which by individuals? And what goods and services do we want more of, and what less?

October 17, 2022

(Non) lessons of the fiasco

All of us tend to interpret political events as confirming our prior beliefs. We must, however, resist this temptation when thinking about the now-reversed Kwarteng/Truss Budget. There are two interpretations of this fiasco which are not as robust as you might think.

The first one is that it shows that small state conservatism is impossible. I don't think this inference is warranted.

Imagine that Budget had been announced at a time of recession when inflation was below target and both short and long-term interest rates near zero. In such circumstances, I suspect markets would applaud: looser fiscal policy is the right thing to do then - as many of us were saying in 2010-12. Yes, bond yields would rise - but that's natural and desirable as a consequence of escaping recession, and it's possible that gilt losses would be accompanied by share price rises.

Of course, we would quibble with the redistributive impact of cuts to top taxes, and we'd argue that spending rises would be better at reflating the economy than tax cuts. But in macroeconomic terms, the Kwarteng-Truss Budget would have been acceptable.

And a few years after the Budget, Kwarteng/Truss could claim not only that they had averted recession, but also that subsequent growth had been good. Yes, orthodox economists would reply that this was due more to standard accelerator effects and diminished uncertainty than to supply-side effects of tax cuts. But that's the point: we would be debating whether tax cuts had worked. We wouldn't be claiming that the Kwarteng/Truss approach had been refuted.

This counterfactual tells us that the fatal flaw in the Kwarteng/Truss Budget was its macroeconomic judgement, not its supply-side measures.

Let's try another counterfactual. Imagine their Budget had been announced after a positive supply shock - something that had both boosted growth and reduced inflation. Tax cuts would then look "affordable", because the stronger economy had reduced government borrowing. Nobody would panic. The way to shrink the state, remember, is to have a strong economy.

What would such a supply shock be? One candidate would be sharp reversal of this year's oil and gas price rises. The right, however, might add another candidate: non-fiscal supply-side measures such as planning reform. On that view, the Kwarteng/Truss error has been to do policy in the wrong order: tax cuts should have followed other supply-side policies, not preceded them.

Now, personally I am of course very sceptical that cuts to top tax rates would greatly stimulate the supply-side. But this scepticism is not enhanced by the Tories' latest fiasco. What this proves is that their macroeconomic and market judgement is atrocious. It does not prove that rightist supply-side measures are always doomed to fail. To establish that, you need other evidence.

There is another hypothesis which I think is unproven by recent events. This is that, contrary to the claim of modern monetary theory, bond markets are in themselves a constraint on government borrowing.

My problem with this idea is that we've seen bonds sell off at a time of high inflation. It is possible that what gilt markets are worried about, therefore, is not a flood of issuance but simply that tax cuts will further add to inflation. On this view, MMTers are right. It is indeed inflation that is the constraint upon government borrowing. Bond markets are merely a mechanism through which this constraint becomes obvious to government.

Of course, something would refute MMT - if we were seeing bonds sell off at a time of low inflation. But this is not what's happening.

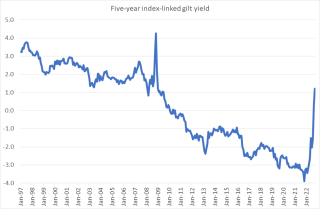

There is, however, a wrinkle here. What we've seen since the summer is not just a rise in nominal gilt yields but also a sharp rise in real ones too. You might think this consistent with the market fearing a glut of debt, not just inflation - that markets are, in Paul Krugman's words, pricing in a "moron risk premium."

Possibly, but not certainly.

For one thing, this risk premium might reflect not the quantity of debt but rather the manner of conducting policy: in sacking Sir Tom Scholar and sidelining the OBR, Kwarteng/Truss signalled that they were heedless of dissonant voices. That's just bad policy-making.

For another, higher real yields are themselves a sign the markets fear inflation. Real yields are higher because markets expect higher real short-term interest rates. Which is just what should happen as the Bank tries to reduce inflation.

And for a third thing, even now real yields are well below their 1990s levels. In a longer-term context the bond market vigilantes are still softies.

This issue matters for how the left should think about fiscal policy. If the problem is indeed too much borrowing then there might be a case for wealth taxes merely to raise revenue. If, however, the problem is inflation then wealth taxes are a less good solution: insofar as the rich don't spend their wealth, such taxes won't much reduce inflation.

My point here is to try to lean against the old habit of seeing our prejudices confirmed everywhere. Macroeconomics and politics are often afflicted with the Duhem-Quine problem, that hypotheses can never be tested in isolation. Recent events do not prove that small-state supply-side policies are impossible, and nor do they prove that the bond market and not inflation is the constraint upon borrowing. Maybe they are, maybe not - but this fiasco does not establish so much.

Instead, it proves just one thing - that the Tory reputation for economic competence was not justified. And perhaps it never was.

October 6, 2022

Origins of the Tory implosion

The implosion of the Tory party suggests I was wrong.

I had thought that economic stagnation - which has seen real wages fall below 2007 levels - would benefit the Tories. As Ben Friedman showed, a weak economy leads to illiberalism and reactionary politics which creates a constituency for culture war politics and attacks on migrants, "wokesters" and the EU. Also, the low real interest rates caused by stagnation sustain house prices thus giving older home-owners an illusion of wealth, whilst at the same time boosting the profits of some financiers who back the Tory party.

This seemed to be the case until recently: the Tories led Labour in the polls until this year, and even in the summer had only a small deficit. But no longer. Labour now has a 30pp lead, predicting the wipeout of the Tory party at the next election.

So what changed?

Putin, that's what. His invasion of Ukraine caused energy prices to soar, with the result that the cost of living crisis increased in salience, whilst culture wars diminished. Which has revealed a division in the Tory party.

This division arises from a brute economic fact. You can have both low taxes and decent public services only if you have a strong economy: history tells us that the shares of taxes and state spending in GDP are driven more by economic fluctuations than by government ideology.

Fifteen years of economic stagnation therefore forces Tories to choose: you can have tax cuts, or you can avoid cuts to welfare benefits and public services. But you cannot have both.

For years, the Tories have dodged this question by talking little about economics and more about culture wars, of which Brexit is a part. That is now no longer an option: those Tory MPs who moan about migrants and Harry Potter courses at universities merely embarrass themselves.

Kwarteng tried to dodge this question by pretending that tax cuts would stimulate growth or that the government could easily borrow to cut taxes. Neither claim survived more than a few days.

For one thing, there is little (pdf) evidence that lower taxes do stimulate growth. The UK economy grew much better when the Kinks complained that "the taxman's taken all my dough" than it did in the years after Nigella's dad cut the top rate to 40%*.

And for another, government borrowing has gotten more expensive: five-year nominal yields have jumped from 0.8% to over 4% so far this year. That's partly because of a rise in global yields, and partly because we are now closer to full employment and the point at which looser fiscal policy leads to inflation rather than real growth. It's also because the government has reduced confidence in UK assets by sacking Sir Tom Scholar and sidelining the OBR; the US can afford to elect a braindead ideologue because it has exorbitant privilege but the UK cannot be so cavalier about international perceptions and so doesn't have that option.

The Tory dilemma is therefore acute: tax cuts or public services? Of course, many Tories have an ideological instinct for tax cuts. But they also have a predilection for "sound finance" and - even more so - for getting elected. And with voters not wanting a smaller state (pdf) they cannot have all three.

Let's be clear, though. The issue here is not only ideology and electoral considerations. Underpinning it is 15 years of economic stagnation. Just as poverty-stricken individuals face horrible choices, so too do countries. In fairness to them, Truss and Kwarteng realize this - hence their concern to raise economic growth. Sadly, though, they are unaware that achieving this requires years of hard slog and that the enemies of growth exist in their own party - in Brexiteers, nimbys and financiers and rentiers who benefit from the low interest rates that stagnation usually brings.

The Tories had the luck or skill to avoid these choices for years by fostering culture wars, which led me to think stagnation would continue to benefit them. I was wrong, because economics has now become the centre of party politics again. Tory divisions and unpopularity are not just the unfortunate result of having profoundly inadequate personnel. They are the product of underlying economic forces.

* Between 1948 and 1971 (when the top income tax rate averaged 90%) UK real GDP grew by an average of 3.3% a year: since 1988, when it was cut to 40%, it has grown only 1.9%.

Another thing. All this, I think, is an example of a point the great Jon Elster made in Nuts and Bolts for the Social Sciences. The social sciences, he wrote, are a box of mechanisms. But we often cannot foretell which mechanism will operate more strongly. So whilst there are some mechanisms linking stagnation to Tories thriving, there are others linking it to their demise. What we've seen is a shift from one to the other. As Elster wrote, "sometimes we can explain without being able to predict." (Personally, I don't see this as a great defect in the social sciences - but that's another story.)

September 27, 2022

The full employment question

"Never mind the public finances. Look after the economy and the deficit will look after itself." For years, critics of George Osborne such as me echoed Keynes' old line. At last, the Tories are, by their own lights, heeding this call. And financial markets hate it. Does this mean the Keynesian advice was wrong all along?

No. There's a big difference between the 2010s and now.

This difference is not that Kwarteng is mistaken to think that tax cuts will stimulate long-term productivity growth. He probably is, but this isn't the main problem. Even if he had announced the best supply-side policies imaginable, these would not have a significant impact on the economy in the next few months simply because it takes time for capital and labour to learn of new and better opportunities and move to them. As Banerjee and Duflo showed in Good Economics for Hard Times, economies are sticky and slow to adjust to change.

Instead, we are closer to full employment now than we were ten years ago. And full employment changes how macro policy should be conducted. When there is unemployment any fiscal policy that boosts aggregate demand will lead to the greater utilization of unemployed assets (capital and labour) and hence to increased real output. At full employment, however, this cannot happen and so we get inflation instead. Tax cuts might have boosted growth ten years ago when there were idle resources, but now we are nearer to full employment they are more likely to lead to higher inflation.

Which is what financial markets expect. Their fear of higher inflation has driven five-year gilt yields up to 4.4%, compared to only 1.4% as recently as May*.

This raises three issues.

One is: how much will this fiscal stimulus add to demand? In this context, the fact that the tax cuts are skewed to the rich is a good thing: the rich have a high propensity to save and so won't boost aggregate demand and inflation much. But even so, the impact is positive - as of course is the impact of capping energy prices**.

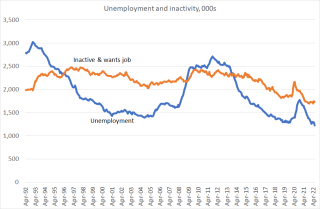

A second issue is: how close are we actually to full employment? The official jobless level is just over 1.2m. That's less than the number of vacancies, and its lowest since 1975. On top of this, though, there are 1.7m people out of the labour force who would like a job. Adding these to the officially unemployed gives us a level of 2.9m, which is the lowest since data began in 1992. Official figures show that there are also 2.8m people who are working fewer hours than they'd like - although this is the lowest number since before the financial crisis.

Whether such numbers mean we are actually at full employment is moot: there's always some frictional unemployment and under-employment simply because of mismatches between supply and demand***. What we can say, though, is that we are much closer to full employment than we were ten years ago. Back then there were one million more under-employed and two million more unemployed and inactive wanting a job. Which means it is plausible that a given boost to demand now will lead to a worse output-inflation mix than it would have done in 2012.

Thirdly, even if we are at full employment, is this inflationary? In the past companies have responded to high demand by figuring out (pdf) ways to raise productivity. That's one reason why full (male!) employment in the 50s was not inflationary. But markets can be forgiven for doubting whether a repeat is possible. For one thing, forty years of mass unemployment has made bosses lazy: in relying upon abundant labour they've lost the habit of thinking how to raise productivity. For another, high policy uncertainty deters companies from investing in the capital equipment that might raise productivity. And for yet another, high demand now is less likely to lead to a big influx of migrant labour, in part because sterling wages no longer buy so much in foreign currency.

It's likely, therefore, that a fiscal stimulus today will be more inflationary and less good for output than it would have been ten years ago. Hence the market reaction.

It's in this context that Sunak's health and social care levy made sense. if we want more health and social care the question is not: where will the money come from? It can be borrowed. Instead, it is: where will the real resources come from - the carers, nurses and premises for care homes?

When there is mass unemployment, the answer's simple: they come from the dole queue and vacant property. At full employment, however, the answer is different: they must come by shifting people from one employment to another. The logic for higher national insurance contributions was that it would do this: it would depress consumer spending and hence facilitate a shift in labour from retail and hospitality to the care sector.

Granted, the implementation of the policy should have been better, for example in helping people more to retrain as health and care workers. But the macroeconomic logic was sound, assuming we were near full employment. Today's Tories are rejecting this logic. That wouldn't be a problem if there was significant unemployment. But there might not be, and indeed Kwarteng's attempts to cajole UC claimants into working more suggests that he believes there is not.

Now, you might question the facts here. Maybe we are still some way from full employment, or maybe our nearness to it won't be as inflationary as feared.

For my purposes, however, this is not the point. The point is that the policy that's right for unemployment is not the same as that which is right for full employment. Macroeconomic economic policy should be a merely empirical matter, not a matter of ideology or sloganeering. In this respect, however, the Tories have been consistent: they were wrong in the 2010s, and might well be wrong in the 2020s. But that's the thing about them: they are so much more ideological than we Marxists.

* Granted, all the rise is due to a rise in real yields: Bank data shows that inflation expectations have actually come down since then. But that is because markets expect rate rises to curb inflation: higher mortgage rates will crater discretionary consumer spending.

** Yes, the price cap cuts inflation as a mathematical fact. But it raises it as a behavioural one: because we'll have more money to spend than we otherwise would, demand will be higher which is potentially inflationary.

*** From a macroeconomic point of view, "full employment" is defined as the unemployment rate at which inflation takes off. This need not be the same as full employment from a human point of view.

September 13, 2022

Why do we want free markets?

There's a paradox: Liz Truss's government contains many members who claim to be free marketeers, and yet the first policy of her premiership has been to freeze energy prices and subsidize energy suppliers.

This poses the question: what does it mean to be a free marketeer today? One way to consider this is to ask what's so good about markets anyway, and whether these values can be strengthened (or even salvaged) in today's economy.

First, though, let's remember what are not arguments for free markets.

It is not the case that they yield "optimal" outcomes. Yes, they do so in theory, but only under conditions which have never actually existed.

Nor is it the case that free markets are "natural" and government "interventions" therein artificial. As Jesse Norman wrote in his excellent Adam Smith: what he thought and why it matters: "It makes no sense to speak of humans in a state of nature prior to society, because humans are social by nature." And in Free to Choose (pdf), Milton Friedman said: "There is nothing 'natural' about where my property rights end and yours begin." Sensible defenders of a market economy have always acknowledged that it rests upon the foundation of a well-functioning state.

Still less is it the case that markets deliver economic stability. Perhaps the nearest we have come to a free market was in 19th century England and the US. But both saw frequent recessions: 15 in the US between 1857 and 1914 according to the NBER, whilst the UK saw 13 calendar years of falling real GDP between 1846 and 1914. Still less do markets deliver social stability: an essential feature of them is the creative destruction that wipes out the industries on which some communities depend.

If these are not the virtues of markets, what are?

Let's start at the beginning, with Adam Smith. His phrase, "the invisible hand" appears only once in the Wealth of Nations as an almost throwaway remark. Instead he, like his kindred spirit Edmund Burke, devoted far more time to excoriating monopoly - the East India Company. It, he said, not just "oppresses and domineers" Indians but also impoverishes the English:

Since the establishment of the English East India Company, for example, the other inhabitants of England, over and above being excluded from the trade, must have paid in the price of the East India goods which they have consumed, not only for all the extraordinary profits which the company may have made upon those goods in consequence of their monopoly, but for all the extraordinary waste which the fraud and abuse, inseparable from the management of the affairs of so great a company, must necessarily have occasioned.

For Smith, the antithesis of the free market was not big government but monopoly and privilege. And well-functioning free markets attack privilege by allowing new companies to compete away the profits of erstwhile monopolies. They are an egalitarian device. Every billionaire is a market failure. As Jesse Norman wrote:

High profits over any sustained period are a sign for Smith of poorly functioning markets...They're associated with poorer, not richer, societies; and with failure not success.

Free marketeers in the Burke and Smith tradition cannot defend water companies which, like the EIC, are pure monopolies. Nor can they be happy with sustained profits of any business, insofar as these might well be signs of barriers to entry and inadequate competition.

Smith saw another virtue in well-functioning markets. For him - as Norman stresses - markets both require and cultivate sympathy. If you want to thrive in a competitive market you must put yourselves in the shoes of the customer by asking: what does he want? This simple act leads to a fellow-feeling in a way that relations of domination and subjection do not. And repeating the act leads naturally to an extension of that fellow-feeling into other domains. Which is why Montesquieu thought that commerce ���polishes and softens barbaric ways.��� Richard Cobden, for example, was not just an anti-Corn Law campaigner but also a pacifist.

One manifestation if this today is "woke capitalism": in an effort to shift product, some companies profess to support liberal causes. Granted, such claims can be hypocritical - hypocrisy is the tribute vice pays to virtue - but no free marketeer in the Montesquieu tradition can object to them.

The opposite of a great truth, though, is another great truth. G.A. Cohen has said that markets lead us to view others as either threats or potential sources of enrichment which are, he wrote, "horrible ways of seeing other people." This is more likely to be true when markets don't function well. Water companies pouring shit into the sea; Royal Mail bosses taking big bonuses whilst demanding that workers take pay cuts; and scammers looking for new marks validate Cohen's view more than Smith's.

Another virtue of free markets - stressed by Friedman and Hayek - is that economic freedom is associated political freedom. As Friedman put it:

A predominantly voluntary exchange economy...has within it the potential to promote both prosperity and human freedom. It may not achieve its potential in either respect, but we know of no society that has ever achieved prosperity and freedom unless voluntary exchange has been its dominant principle of organization (Free to Choose, p11)

Smithian sympathy is one mechanism here. If our economic transactions lead us towards a fellow-feeling for others, we'll be more likely to want him to have political freedom. And if we are free to choose our butcher or coal merchant, we will want to be free to express our political or religious opinions.

This argument for freedom, however, runs into the obvious Marxian objection. Whereas markets are, he said "a very Eden of the innate rights of man", they lead to the exploitation, domination and unfreedom of the worker, who "is bringing his own hide to market and has nothing to expect but - a hiding." The free marketeer who values real freedom will thus support measures which prevent workers being forced into egregiously degrading work - such as policies to promote full employment or a basic income.

Well-functioning free markets don't just foster equality, freedom and civility, though. They can also enhance economic efficiency.

One way they do so was stressed by Hayek. A great virtue of markets is that they aggregate dispersed, fragmentary and fleeting information into one simple fact - a price - and so facilitate better, quicker decision-making:

We need decentralization because only thus can we insure that the knowledge of the particular circumstances of time and place will be promptly used...in a system in which the knowledge of the relevant facts is dispersed among many people, prices can act to co��rdinate the separate actions of different people.

Of course, this doesn't always work effectively. In asset markets especially agents can misinterpret prices thereby "chasing noise" and creating bubbles. But for free marketeers following Hayek, it is an advantage over state direction.

There are, however, some corollaries of this from which some free marketeers resile.

One is that a lot of private sector economic activity consists in overlooking dispersed localized information. Large companies are centrally planned economies in which workers' knowledge is ignored or effaced: Harry Braverman's beef with scientific management was that it destroyed craft knowledge. There's a Hayekian case for worker democracy (pdf).

Another is that oligarchic mass media might have a pernicious influence. Insofar as it gives excessive weight to a few very similar points of view it over-rides localized dispersed knowledge and causes ideas to become more correlated across people. That weakens the conditions necessary for there to be wisdom in crowds.

A further way in which markets facilitate efficiency is by sharpening incentives. Friedman said that when you spend your own money on yourself "then you really watch out what you���re doing, and you try to get the most for your money." By contrast:

If I spend somebody else���s money on somebody else, I���m not concerned about how much it is, and I���m not concerned about what I get. And that���s government.

It's for this reason that free marketeers should be queasy about the government's plan to cap energy prices. Yes, there's a case for intervention: gas prices are high largely because of Putin's invasion of Ukraine, which is not market activity. But the cap means that rather than spending our own money on our energy, the government is spending other people's money on it. That weakens incentives to curb energy use. Sunak's policy of letting prices rise but giving lump sums to every household was, from this perspective, closer to a free market solution.

But, but, but. Not all private sector economic activity consists of us spending our own money on ourselves. Fund managers spend somebody else���s money on somebody else - which is why hedge funds thrive despite poor returns. Likewise, the investment decisions of large companies mean people spending other people's money, with often lacklustre results.

The point here is that not all private sector economic activity delivers the goods of liberty, equality or efficiency. Where there is monopoly, or the opportunity for egregious exploitation, or agency failure, then the case for free markets diminishes. You can therefore be a free marketeer whilst opposing private sector monopolies such as the utilities, favouring financial regulation or supporting institutions such as trades unions. Markets best facilitate the virtues claimed for them when they operate within the right cultural and institutional framework. As Jesse Norman wrote:

Markets are sustained not merely by incentives of gain or loss but by laws, institutions, norms and identities.

Economies performed much better - in terms of faster and more equitable growth - in the post-war period than they have since the 1980s, not least because norms and institutions (one of which was strong trades unions) facilitated that.

As Edmund Burke said:

Circumstances (which with some gentlemen pass for nothing) give in reality to every political principle its distinguishing colour, and discriminating effect. The circumstances are what render every civil and political scheme beneficial or noxious to mankind.

From this perspective, free marketeers must be saddened by rising energy prices just as they bewail increased state spending - because both mean that the proportion of economic activity devoted to beneficial market activity is shrinking.

By now, some of you will think I'm being horribly naive. "Free marketeers", you might say, are not those who believe that some markets, in some conditions, promote virtues. Instead, they are just shills for monopolists and rent-seekers. You'd be right. Just as the left should reclaim the cause of freedom from the right so too should it reclaim the cause of free markets. To the faux free marketeers on the right we should paraphrase the Muslim speaking to the terrorist: "You ain't no free marketeer, bruv".

August 30, 2022

In praise of Enough is Enough

One of the few silver linings to the cost of living crisis has been the re-emergence of trades union power and the start of the Enough is Enough campaign. These could potentially be the start of a new and better politics.

As Enough is Enough say:

We can���t rely on the establishment to solve our problems. It���s up to us in every workplace and every community.

This is a challenge to Labourism, in which as Ralph Miliband put it, the Labour party "have treated the voters not as potential comrades but as possible clients." It is a rejection of retail politics, in which people are victims of policy and not contributors to it, mere passive consumers who wait until a general election to make their choice.

Which is to be welcomed, because what matters in politics is not intellect but power. Brexit did not come to dominate the agenda because it was the best idea around, but because it had influential and rich supporters. Living standards cannot be adequately protected merely by appeals to decency or reason. They must be protected by force. A stronger, more organized and more vocal working class is one such force.

The right has for decades practiced extra-parliamentary action, through "think" tanks; control of the mass media; corporate lobbying; regulatory capture; the promise of lucrative jobs to MPs on leaving office; and so on. Which is why the interests of the richest 1% dominate policy-making. To believe that Labour can win office and implement pro-worker policies in the face of the pressures created by such action is like thinking you can win a marathon by turning up in your brogues without doing any training.

Policy-making is driven by the fear of losing office. We need the Tory and Labour parties to fear the working class as much as they have feared the racist rabble aroused by Farage. In this sense, the trades union movement is what J.K. Galbraith called a countervailing power - a balance to the influence upon government of capitalists, racists and assorted fantasists. It was this that humanized the Tory party under Macmillan in the 1950s. Owen Jones is surely correct to say that it is the fear of the mob on the streets that inhibits attacks upon people's living standards. As Tony Blair said, what matters is what works.

Such countervailing power, however, brings something else - cognitive diversity. As Peter Allen argues in The Political Class, "inclusive decision-making results in better outcomes than its exclusive counterpart". A voice for the organized working class forces the Westminster bubble to heed real problems such as living standards rather than culture war fantasies. It reminds politicians and journalists that there is more to politics than the voices in posh people's heads.

From this perspective, the re-emergence of working class voice is the start of a reversal of a project begun under Thatcher, well discussed by Phil Burton-Cartledge in Falling Down. He describes how she wanted to restore state authority so that the relationship between state and individual was unmediated by any other independent authority, be it local government, a neutral civil service, or trades unions. You can interpret the Tories' hold over the BBC, its dismissal of experts, and the Daily Mail's describing judges as "enemies of the people" as extensions of this tradition. Believers in limited government should therefore welcome Enough is Enough as a constraint upon government.

So too should democrats. The value of democracy lies to a large extent in the idea of political equality. This requires that a worker have as much political influence as a newspaper proprietor. Stronger unions nudge us slightly towards this direction.

Of course, in saying all this I might be claiming too much. Enough is Enough is, as Phil says, only a beginning. We've seen activist movements come and go before: think of Occupy. Whether the revival of unionism can withstand the coming recession and rise in unemployment - not to mention the capitalist media backlash - remains to be seen. Nevertheless, it offers hope - and that, right now, is scarce and valuable.

August 1, 2022

Energy bills: rentiers vs entrepreneurs

Everybody knows that soaring utility bills will plunge millions of people into desperate poverty in the autumn. Even those who don���t care about those on low incomes, however, should worry ��� because such huge price rises are a threat to economic dynamism, entrepreneurship and the free market.

I say so for a trivial reason ��� that if we are handing more cash over to utility companies, we���ve less to spend elsewhere. Even if you are on a decent income, having to spend an extra ��150 a month on gas and electricity will cause you to cut your discretionary outgoings.

For some, these outgoings will be savings or pension contributions: they will pay for their electricity by working later into life. For others, it will mean less spending on goods and services. Already people are cutting subscriptions to streaming services whilst non-petrol retail spending has fallen steadily over the last 12 months. Such cut-backs will intensify in the autumn. I wouldn���t want to be a publican or restaurateur facing the double danger of soaring costs and falling discretionary spending.

What we���re seeing, then, is a transfer of real resources away from competitive entrepreneurial sectors of the economy towards rentiers ��� those who can get rich merely by owning scarce assets such as gas and oil fields.

This could reduce economic dynamism and productivity, simply as more of our spending goes on sectors with low productivity growth and less on higher-growth sectors.

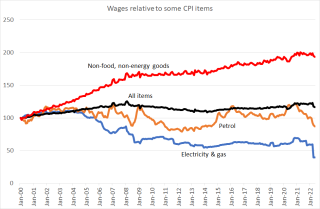

My chart provides context here, showing real wages since 2000 relative to some CPI items. The point is that there have been enormous changes in relative prices, even before October���s leap in utility bills. Relative prices of goods such as clothing, TVs and phones have fallen sharply this century ��� so much so that an average wage will now buy almost twice as many of them as it did in 2000. Prices of gas and electricity (and to a lesser extent petrol) have, however, risen sharply, so that wages buy only half as much of them as they did in 2000*.

As we spend more on the latter, however, the weight in the economy of dynamic sectors declines. The upshot is that productivity and dynamism dwindle.

What I���m suggesting here echoes an old idea ��� David Ricardo���s theory of rent and profits. As the population expands, he said, so too will demand for food. That means that the most fertile land would become more scarce, allowing its owners to charge monopoly rents:

By bringing successively land of a worse quality, or less favourably situated into cultivation, rent would rise on the land previously cultivated, and precisely in the same degree would profits fall; and if the smallness of profits do not check accumulation, there are hardly any limits to the rise of rent, and the fall of profit.

In a similar way, growing economies need more gas and oil, which means that worse-quality gas and oil fields must be employed ��� those where the products are more difficult to extract or those located in hostile countries such as Russia. The result is a transfer of real resources to the rentiers who own better-quality fields and away from incomes in the rest of the economy. The effect of that might well be to ���check accumulation��� ��� to depress growth. As Ricardo said:

The interest of the landlord is always opposed to the interest of every other class in the community.

Which is why I say that anybody who values dynamism, entrepreneurship and a thriving market economy should be alarmed by soaring oil prices ��� even if they don���t give a damn about the poor. They are also a threat to all non-energy businesses, especially if they use a lot of energy or are dependent upon discretionary consumer spending.

The danger isn���t only at the economic level, however. It���s also political. Soaring energy prices will bring into question both the fairness and efficiency of our neoliberal** system. So far, the discontent is manifesting itself only in pockets of wage militancy, but it could spread further.

So, what���s the solution?

The government could freeze the energy price cap: give households more cash: or cut VAT or green levies. The first entails energy suppliers borrowing during the crisis, the other two government borrowing. Both, however, are predicated upon assuming that high energy costs are only temporary. Yes, they might be, but such an assumption overlooks the fact that real wages were stagnating (and falling relative to gas and oil prices) before Russia invaded Ukraine.

Nor is nationalization, in itself, an answer. It is, at best, a device for ensuring that energy companies serve socially-determined ends. To do this, however, we need to decide what those ends are: for example, do we want high prices to encourage people to economize on fuel alongside income support; do we want lower prices and the greater energy usage they stimulate; how much extra investment do we need, and in what?

There is, though, something else ��� something in the spirit of Ricardo. For him, the problem was that landlords were owners of a monopoly asset (fertile land) and so could extort high rents. The answer to this, he thought, was to weaken that monopoly either by technical progress which improved less fertile land or by allowing the free import of corn. Both, in effect, created competition to that best land and so reduced its monopoly power ***.

In the same vein, what we need is greater competition to gas and oil suppliers. As Eric Lonergan has brilliantly shown, we need to create substitutes for them by greatly stimulating the supply of renewable energy and technologies that use less carbon such as electric cars:

You need perfect substitutes and a small price advantage, or near-substitutes and a large price advantage, to dramatically affect behaviour���. We need to mobilise investment in substitutes, ensure they are ���close��� enough for the user and that they are priced more favourably than the emissions intensive option.

This, I suspect, requires a broad spectrum approach including tax incentives, state aid and an attack nimbyism: there���s no reason why our motorways shouldn���t be lined with windmills or solar panels. The point is to attack the monopoly power of rentiers whose interests are ���opposed to the interest of every other class in the community.���

In this sense, Tories face the same question now that they did in the 1840s when the conflict described by Ricardo fuelled fierce debate about whether to abolish the corn laws; are they on the side of rentiers who are blocking economic growth, or that of entrepreneurs? Not only are they not answering this question, however, they do not even seem aware of its existence.

* You might wonder what���s happened to rents. The answer is: not much. These have risen roughly as much as wages over time ��� perhaps because landlords have always charged as much as they can.

** I know some of you don���t like that word. But I can���t think of better: what we have now is certainly not a free market system.

*** Ricardo saw free trade and better technology as being very similar. Which they are: both give us cheaper access to things that were previously expensive or unobtainable.

July 25, 2022

The futility of economic policy debate

Sam Bowman writes on the divide between boosters and doomsters - those who believe we can boost economic growth and those who don't. He misses, however, an important point.

This is that economic policy is not made by Sam, nor by Giles Wilkes, Stian Westlake, Aaron Batani or Torsten Bell. Policy-making (at least in the UK now) is not a meritocracy in which the people with the best ideas get the most say. Nor of course is it a democracy in which we all have equal say.

Instead, a mere glance at the Tory leadership contest (and a mere glance is all any of us can stand) tells us that policy is made not by the masses, nor by those of ability, but by those who can best appeal to a small minority who have little knowledge of economics and little desire for higher growth.

Given this, talking about what policies will raise growth is futile*. It begs the question: how can we create a polity in which sensible economic policy is even feasible?

The problem is that there are many structural barriers to growth-enhancing policies.

One was described by Joel Mokyr almost 30 years ago:

Sooner or later the forces of conservatism, the "if-it-ain't-broke-don't-fix-it," the "if-God-had-wanted-us-to-fly-he-would-have-given-us-wings," and the "not-invented-here-so-it-can't-possibly-work" people take over and manage through a variety of legal and institutional channels to slow down and if possible stop technological creativity altogether.

These forces of conservatism block some policies that could boost growth. Landlords would oppose any measures to reduce house prices or to shift the tax base from incomes to land. Lawyers and accountants don't want tax simplification (one good benchmark for any Budget should be the question: how many accountants will it make redundant?) Nimbys oppose inrastructure spending, even if it is green. And incumbent companies oppose tougher competition policy, or even anything that fosters business start-ups.

I'd add that the financial sector generally is such a force of conservatism. it benefits from the low real interest rates that stagnation brings. Sure, General Motors favoured pro-growth policies in the 50s as it needed a mass market. But Goldman Sachs has much less need.

Pablo Torija Jimenez and Martin Gilens and Benjamin Page (pdf) have shown how policy is set with regard to the interests of the mega-rich. But many of these are opposed to the reforms necessary to boost growth.

Rentiers, though, aren't the only force of conservatism. Back in 2006 Ben Friedman showed that economic stagnation fuelled illiberalism, racism and reactionary politics. Subsequent events have proved him right. But this means there's another big constituency opposed to growth, and not just gobshite culture warriors such as Farage or GB News. Why should Tories trouble themselves with the tough thinking and difficult admin required to raise economic growth when they can win elections simply by promising to deport migrants?

Yet another such force, of course, is the media. And I don't mean only the mouthpieces of tax-dodgers, rentiers and racists. I'm thinking too of our most influential outlet, the BBC. As Simon Wren-Lewis has documented, it has for years thought of economic policy merely as being about "the nation's finances" with good policy being only about fiscal responsibility - which is of course oblivious to basic economics.

We heard an example of this error on the Today programme this morning, when the interviewer accepted Rachel Reeves' claim that nationalization was inconsistent with Labour's proposed fiscal rules thereby missing the big story - that Ms Reeves is unqualified to be Chancellor because she doesn't know the basics of double-entry book-keeping.

The media, though, is not the only barrier to sensible policy-making. So too are voters. A vote for a hard Brexit was a vote against economic growth. Sure you might think this was because voters were misinformed about its economic effects. But this only raises the question: if they ignored good economics on Brexit, what makes you think they'll accept good ideas to raise economic growth?

I fear there's another issue here - a form of what John Jost calls system justification (pdf). 15 years of stagnant incomes has merely led to resignation, adaptation and learned helplessness. Many voters think we just cannot have nice things, and that any party offering them is dealing in fantasy economics.

Of course, good economists are having the debate Sam describes, of whether policy can raise growth**. But this debate is like writing a menu when you don't yet have a kitchen nor even much hope of ever getting one. Before thinking about economic policy we must think about how to give sensible economics any political influence. Brains are not enough. What matters is power.

I confess to not having answers here. Part of the answer, though, I suspect is to build and support movements which offer countervailing power to the forces of conservatism - movements which tell politicians that there are costs to them of kowtowing to rentiers and reactionaries. This is why some of us welcomed the mass politics inspired by Corbyn - but also, of course, why that met with swift repression.

* Well, maybe not entirely. Such talk could be a transitional demand - a way of saying "here's what you could have if our system wasn't so dysfunctional", and thus a way of raising discontent with the system.

** FWIW, I incline to the doomster camp but believe that many potentially growth-boosting policies (tax reform, better immigration policy, competition policy, better vocational training) are free hits: even if they don't boost growth much, they'll not hurt it either.

Chris Dillow's Blog

- Chris Dillow's profile

- 2 followers