Chris Dillow's Blog, page 8

July 20, 2022

Tories' structural stupidity

There���s widespread dissatisfaction at the low intellectual quality of the Tory leadership contest, with no candidate having any answer to our long-term productivity stagnation or cost of living crisis. As Phil says, they are ���lightweights with no answers to the serious problems the country faces.��� The Tories themselves share this discontent, having cancelled the third leadership debate for fear of the party being further damaged by being seen to be so inadequate.

This acute lack of talent among leadership contenders is, however, no accident. It is not merely a problem of inadequate personnel. Instead, it has its roots in material facts about politics and capitalism.

One is that the mechanisms that select for MPs have changed to reduce the calibre of politicians. Party membership has declined, meaning that cranks have more influence and that local parties are no longer so rooted in the interests of small businesses. And increased inequality means that even half-able people can earn good money outside politics with the result that the latter politics becomes dominated by people not good enough for careers in business or finance.

One of these selection mechanisms is our general culture. Nadine Dorries and Penny Mordaunt raised their profiles by eating ostrich arse and belly-flopping in a swimming cozzie, whereas Jesse Norman���s fine books on Burke and Smith did nothing for his appeal. That tells us that there has been a general dumbing-down which selects against people of ability.

The media is of course part (but perhaps only part) of the problem here. There mere fact that it devotes time to asking what is a woman at a time when the planet is on fire, the economy trapped in long-term stagnation and real wages are collapsing shows that it is the enemy of intellect and seriousness.

But there���s more than this. Even if Tories had the ability to find economic ideas, they don���t have the incentive. Voters don���t want economic growth: they voted against it in 2015, 2016, 2017 and in 2019. And why should they want it? Economic growth entails creative destruction which undermines communities and generates uncertainty. It means higher real interest rates, which would cut house prices and reverse the financialization from which Tory donors have greatly benefited. And, as Ben Friedman has shown, growth increases liberalism and tolerance which would diminish the Tories��� ability to fight atavistic culture wars.

We can put this another way. There���s a big difference between Thatcher and her epigones. Thatcher had clearly defined enemies (���the enemy within���) which she saw as barriers to economic growth: trades unions and nationalized industries. But who are today���s enemies? They are those the Tories cannot identify as such: monopolists, financiers and rent-extractors. Yes, Suella Braverman did try to portray benefit recipients as the enemy, but this was not so much economic analysis as soiling herself in public.

But the Tories have another problem. The last three Tory approaches to the economy were all one-off, time-limited. On a kind reading (there are others!) Thatcherite reforms raised potential GDP but output has long since converged to that higher potential, meaning that other growth-enhancing policies are needed. But what? Tory/Lib Dem austerity has left the NHS, local government and the criminal justice system semi-derelict, meaning that spending cuts are just impossible. And the thing about "Get Brexit Done" is that you can only do it once unless you look like a charlatan.

The Tories therefore need something new. Which brings us to the fact that the current conjuncture of capitalism makes it very difficult to come up with something. There are three inter-related problems here:

- How much legitimation does the system need, and what form should it take? Historically, one role of the Tory party has been to either suppress discontent (such as the Six Acts or Thatcher���s attacks on unions) or to buy it off (eg Disraeli���s electoral reform or the post-war accommodation to the welfare state and mixed economy). But which should today���s Tories do? Yes, they���ve introduced a windfall tax to ameliorate the most egregious unfairness of the cost of living crisis. But how much further should they go? Would increases in public sector pay and benefits be sufficient vote-winners to outweigh their costs in terms of higher inflation and interest rates? Or could it just garner support by continuing the culture wars?

- Are we in a wage-led or profit-led regime (pdf), to use Marglin and Bhaduri���s framework? Thatcher thought we were in a profit-led regime, wherein attacks on workers would restore profit margins and business confidence and so kick-start economic growth. But this might not be the case today. In curbing consumer demand, weak real wages depress profits and hence motives to invest. Instead, we might now be in a wage-led regime (pdf), wherein wage rises, full employment and stronger worker rights would lead to sustained growth not just by boosting consumer spending but also by encouraging companies to invest in labour-saving productivity-enhancing new techniques. Unless you have an answer to this conundrum, you���ve no hope of having a coherent economic strategy.

- Which sections of capital should the Tories serve? Falling real wages aren���t just bad for workers. They are also bad for those sections of capital dependent upon consumer spending. From this perspective, capital and labour would both win from policies that ameliorate the cost of living crisis. Such policies, however, are potentially inflationary to the extent that they would raise aggregate demand. Given the Bank���s current remit, that would mean higher interest rates and hence lower asset prices. That���s bad for rentier capital. Which is what Sunak means when he says he wants to ���get a grip of inflation���: he doesn���t want to hurt rentiers with unnecessarily higher rates.

These three dilemmas are perhaps more acute now than they were under Thatcher. Which means that the task of developing a sensible economic policy would be daunting even for people of much greater ability than the current candidates.

Many people are complaining that these ��� especially Truss ��� are cosplaying at being Thatcher, with cargo cult talk of tax cuts and (unspecified) deregulation.

True, these are no answer to our problems. The 2008 financial crisis should have taught us that economic growth cannot be achieved merely by the state backing off.

But it���s human nature to retreat into one���s comfort zone when faced with uncertainty. And cleaving to old ideas in the face of contrary evidence is normal. The Labour right does it: it still struggles to face the fact that its no longer the 1990s. And the left ��� certainly in the 80s and 90s and perhaps beyond ��� has also failed to fully adapt to new times. There���s a name for this: Bayesian conservatism. And it���s not confined to politicos: one reason why there is momentum in asset prices is that equity investors cling too much (pdf) to their prior beliefs.

We mustn���t therefore blame the Tory candidates for clinging to Thatcherism.

In fact, talk of their personal weaknesses ��� obvious as they are ��� misses they key point. The fact is that our political structures, incentives and the nature of current capitalism all militate against adequate Tory responses to our crises.

July 19, 2022

Trinkets of frivolous utility

We���re living in an ���age of anti-ambition��� says Elle Hunt. And Stefan Stern says increasing numbers of over-50s are taking early retirement. As one of that happy band, let me suggest why.

It���s because with a modest effort, you can live well on around an average income, having days out, city breaks and good holidays. And ��� which is insufficiently remarked ��� such an income gives you access to the greatest books, films and music (unless you want to go to the opera or god help you, an Adele gig.)

Beyond a certain point therefore ��� attainable by most middle-class 50-somethings ��� the acquisition of wealth becomes futile. There���s not much point buying a big house because you can only sleep in one bed at a time. Fancy cars will just get caught in traffic jams or by speed cameras. Expensive restaurants often serve bad food to the world���s worst people. And cruises are, a friend tells me, the Daily Mail at sea. His point generalizes. Expensive pastimes such as golf, horse-riding or yachting are all excellent ways of meeting people I would pay good money to avoid*.

One look at the mega-rich shows the futility of great wealth. Jeff Bezos, for example, goes on amusement park rides alone and makes brief trips into near-space, thereby only emulating a mid-ranking Soviet Union Air Force officer of 61 years ago. That���s a pathetic return on billions of pounds.

Scientific research corroborates all this. Whilst there is some albeit mixed evidence that money does buy happiness, it does not buy much. That���s why things like a good social life have such high monetary equivalence in terms of their impact on well-being: they, more than money, make for a good life. Which is nasty, because the hours spent accumulating money can prevent you developing a fulfilling social life.

As Porter Wagoner sang

Money can't buy back your youth when you're old

Or a friend when you're lonely, or a love that's grown cold

The wealthiest person is a pauper at times

Compared to the man with a satisfied mind

He was echoing some other great thinkers. Wealth and prestige said Adam Smith ���are mere trinkets of frivolous utility���:

Power and riches appear then to be, what they are, enormous and operose machines contrived to produce a few trifling conveniencies to the body���They keep off the summer shower, not the winter storm, but leave him always as much, and sometimes more exposed than before, to anxiety, to fear, and to sorrow; to diseases, to danger, and to death.

In 1930 Keynes looked forward to the economic problem ��� that of securing subsistence ��� being solved, a stage which some of us have achieved. When this has happened, he wrote:

It it will be those peoples, who can keep alive, and cultivate into a fuller perfection, the art of life itself and do not sell themselves for the means of life, who will be able to enjoy the abundance when it comes.

From this perspective, the question is not why people like me are stopping working or downshifting, but why more well-paid people do not do so.

One answer is that they���ve made imprudent life-choices. Ex-wives, private education for one���s children, drink and gambling habits, yachts, fast cars and a desire to live in London all keep the City supplied with senior staff.

So too does something else. Many successful people don���t regard work as something to be escaped at all, but as a means of fulfilment. Warren Buffett and even Elon Musk think what they are doing is fun. Paul McCartney and the Rolling Stones have kept working into their 70s and 80s, but their contemporaries who became accountants have mostly stopped.

This might help explain why the UK has relatively few unicorn businesses. At some point in a company���s history, running it stops being a fun job of solving engineering and coding puzzles and becomes instead grunt bureaucracy. Why not then sell up to some bureaucrats and live off a few million? There are several reasons: ego gratification; power; prestige; a sense of being a success; or a desire to beat your peers or father. A desire for what money buys, however, is, I suspect, low on the list.

For those of us without these other motives the one great thing that wealth buys is not so much goods and services as freedom ��� the ability to step out of the rat race.

If they���ve read this far, younger readers will be screaming their heads off: ���all this is the solipsism of a privileged boomer.���

Which it is of course. They don���t have my luck in being able to retire early, simply because the unaffordability of housing means that cash that would otherwise go into pension savings is diverted towards mortgage or rent payments or paying off student loans. High energy prices, of course, have the same effect. Rather than save for retirement, as I could in my 30s, today���s young people must support rentiers.

Their righteous discontent, however, demonstrates my point. They take little comfort in consumer goods such as smartphones and flat screen TVs because these are indeed trinkets of frivolous utility. What really matters to them is the freedom that would come from being able to live cheaply ��� a freedom that has been stolen from them.

Capitalism today does a good job of supplying youngsters with new affordable gadgets. But it does not give them the greater goods of real freedom and autonomy.

You might think this is a feature, not a bug. Even if most individuals ��� beyond a point - don���t need to accumulate material goods, capitalism as a system does: accumulation is its very nature. This isn���t a contradiction. For one thing, even if only a minority of rich people do want to become even richer, it is this minority that gets to run companies. And for another, capitalism is an emergent process which constrains even of the privileged and in which outcomes are independent of individuals��� wishes. As Marx said:

Capital is reckless of the health or length of life of the labourer, unless under compulsion from society���But looking at things as a whole, all this does not, indeed, depend on the good or ill will of the individual capitalist. Free competition brings out the inherent laws of capitalist production, in the shape of external coercive laws having power over every individual capitalist.

You might also think that a system that requires the accumulation of profit also requires a big supply of workers. From this point of view, debt bondage is a good thing: it forces people into employment thus enlarging the pool of pliant labour-power. Elementary economics says that if skilled older people drop out of work the economy loses human capital and hence potential output and (more importantly) profits.

In this sense, Keynes was na��ve in thinking that the problem of adjusting to an affluence that makes leisure possible was merely a psychological one ��� a naivete that arose from his lack of a class analysis. The problem is also that capitalism cannot cope with a society of frugal leisure-seekers.

Or can it? Perhaps this view is too harsh on capitalism. Older people can be one of what Joel Mokyr calls the ���forces of conservatism���. They can be cantankerous, hard to manage, resistant to change, and uncomfortable with new technology; to this extent ageism in the workplace has a rational basis. Letting them go might therefore pave the way for productivity improvements and innovation.

Few people claim that the post-mid-2000s productivity slowdown was due to a loss of talented people, nor that the post-1945 productivity surge was caused by an influx thereof. And nor should they. The biggest determinants of productivity are institutions: organizational capital, state capacity, well-functioning markets and so on. Capitalism can survive seeing its more privileged subjects drop out or downshift. Whether it can survive increasingly dysfunctional institutions is another matter.

* In fact, if you come from a poor background and are in a well-paid job the mere act of going into the office will surround you with people you don���t feel comfortable with. This, I suspect, is an under-appreciated cost of social mobility.

June 7, 2022

Johnson's class handicap

There���s a nice and unremarked irony about the impending end of Johnson���s premiership ��� that he is being brought down by the same class structure that took him to Number 10.

It is surely no accident that the vote of no confidence in him took place as soon as possible after he was heard being booed by a crowd of royalists outside St Paul���s.

Those booing him had gone to St Paul���s to celebrate a woman who knows what Johnson does not ��� that wealth and power bring with them responsibility, duty and discipline. Of course, the Queen is absurdly privileged, but the flipside of this is that she has spent seventy years keeping her opinions to herself and meeting some of the most absurd, self-regarding and pompous people on the planet without telling them to go fuck themselves (at least not in so many words). That���s amazing restraint ��� a quality alien to Johnson.

But not one confined to the Queen. For millennia, thinkers have acknowledged that privilege and power can entrap their holders: this was one theme of Xenophon���s dialogue, Hiero. Noblesse oblige and paternalism have not always been myths. In fact, they have sometimes exacted the highest price: in WWI junior officers were disproportionately killed as they led their men over the top.

For Marx, a feature of capitalism was that it constrained capitalists as well as workers. Capitalism, he thought, comprised ���external coercive laws having power over every individual capitalist.���

Those laws were the forces of competition, which Marx thought (not wholly correctly) forced capitalists to drive down wages and working conditions regardless of individual capitalists��� ���good or ill will���.

But competition, or the threat thereof, doesn���t consist only of market forces. Monarchs and tyrants face competition from potential republics or coups and those who ignore this leave messy corpses as Charles I, Louis XVII, Mussolini and Nicholas II (to name but a few) discovered. And political leaders face competition from rivals ��� whether it be deadly competition for crowns or the more benign competition for political leadership.

In fact, capitalism as a system has faced competition within our lifetimes. It���s no accident that inequality declined in many western economies as the threat of communism increased, but increased as that threat diminished. Competition constrains.

Very few of those in positions of privilege, therefore, have unfettered power. They must show restraint not merely out of morality, but because it is necessary to preserve their social position and power.

Those royalists who boo Johnson, and those Tory MPs who want him gone, can see that Johnson isn���t sufficiently heedful of this fact. Even in a polity as deferential as ours, there���s a limit to how much you can take the piss.

It���s a commonplace to blame this upon Johnson���s dishonest incontinent semi-criminal character. But that���s only part of the story. A sensible PM would have stopped those parties in Downing Street not just because of good character or from obeisance to the law, but because he would have asked: ���how will this look if it leaks out?��� Johnson failed to do this. And he did so because of his class background.

His personal history is one of being indulged and forgiven for his many misdemeanours by his patrons and the media ��� an indulgence that would never be extended to the less privileged, be they the lower orders, ethnic minorities or women. Given that he had got away with so much, why shouldn���t he have thought that he could get away with wine and a few nibbles?

But there���s more. In presiding over those parties, Johnson behaved like former Attorney-General Geoffrey Cox did when he went to Brussels in a hapless attempt to negotiate Brexit only to offend his hosts by boasting of not visiting the city for 40 years and calling Sabine Weyand "my dear." Both men made the same mistake ��� of failing to think how their behaviour would seem to others, and so failing to change.

And they didn���t do so because their class background hadn���t prepared them. If you glide through private school to Oxford and then to many professions, you associate largely with those like yourself: sure, you���ll encounter oiks but it is they and not you who are the outsiders who need to fit in. The upshot is that when you need to adapt your behaviour, you���ll be unable to do so. Which is another example of how class traps even the privileged.

Of course, this is not to say that every posh person would have made Johnson���s error: maybe Cameron would not have, who knows? Some can escape the constraints imposed by their class, just as some from poor homes can be upwardly mobile; or some capitalists gain a monopoly position and so are freed from the external laws or competition; or some people escape from prison. The fact that some can free themselves does not mean that the cage does not exist.

If I am right, though, what we have is a nice symmetry: Johnson���s downfall is the product of the same class system that propelled him into office.

May 24, 2022

Capitalism's self-preservation society

Here are three recent items:

- E.On boss Michael Lewis calls for ���very substantial" government help with fuel poverty.

- CBI Director-General Tony Danker says the government must ���help people facing real hardship now���

- Some ���patriotic millionaires��� want higher taxes on the rich: #taxmenow

These people are not revolutionaries nor even moral crusaders, despite Danker���s words. Instead, they see that egregious rates of exploitation, inequality and poverty are not in the interests of at least parts of capital. They want some redistribution and a solution to the cost of living crisis not because of a fit of morality but because they are a self-preservation society.

One reason for this lies in the simple fact of the circular flow of income. Lewis, I suspect, doesn���t give a damn about fuel poverty; if he did he would cut prices himself. What he does care about ��� because he is paid to ��� is that increasing numbers of his customers are in arrears and cannot pay their bills. ���Very substantial��� help for them means very substantial help for him; it improves E.On���s cashflow.

And not just him. Supermarket sales are falling, and discount retailers are gaining market share. That���s another effect of falling real incomes. Anything that boost incomes will help to slow or stop this trend and hence support the profits of retailers. Welfare benefits aren't so much a payment to claimants as a payment through claimants. Which is one reason why Justin Webb isn���t entirely right to claim that a windfall tax on oil and gas companies will hurt pensioners because it will reduce the share prices of Shell and BP. Maybe it will, to an extent. But the revenues generated thereby will be spent in the wider economy, thus supporting profits and dividends elsewhere.

But there���s a second reason why smarter capitalists favour redistribution. It���s that, as James O���Connor pointed out in his famous book, The Fiscal Crisis of the State, capitalism requires more than economic conditions favourable for profits. It also requires legitimacy, which requires that the system be regarded as fair.

This isn���t just because without such a feeling there is a threat of revolution ��� although it might be no accident that inequality in capitalist countries declined after the Russian revolution and increased after the collapse of Communism. It���s also because inequality can generate political uncertainty ��� and as Nick Bloom has shown, this depresses what he calls investment and what Marxists call capitalist accumulation. What���s more, a sense of unfairness is likely to undermine respect for property rights. It���s no accident that retailers are reporting increased levels of shoplifting.

For both these reasons, capitalism sometimes requires a degree of equality not because of romantic notions of justice, but because it is in the interests of capital. Two big facts tell us as much.

One is that in the UK the era of social democratic capitalism was for years better for many capitalists themselves than what followed. UK non-financial company profits rose by 4% a year in real terms between 1948 and 1973, compared to just 2.3% a year between 1979 and 2019.

The other is that the most egregiously unequal nations have rarely been happy places even for investors. Back in 1996 Roland Benabou pointed out that South Korea���s economic performance had far exceeded (pdf) that of the more unequal Philippines. The point broadens: several very unequal countries (such as South Africa, Brazil or Argentina) have delivered poor long-term returns for equity investors because high inequality (pdf) can retard accumulation.

Of course, this is not to tell some just-so story about how capitalism and a degree of fairness can be compatible.

For one thing, the extent of this compatibility depends upon economic conditions and so varies from time to time and place to place. If profit margins are squeezed by worker power and militancy (as they were in the mid-70s), capitalism requires an attack upon workers��� living standards, not support for them.

And for another thing, the interests of capital can themselves conflict. Whereas customer-facing businesses sometimes want decent incomes for the masses, finance capital���s priority is more often low interest rates. Social democratic capitalism might have been good for Ford, but extractive neoliberalism better suits Goldman Sachs.

Which is the context for the Tories��� divisions over the cost of living crisis. Whilst some of them do see that capitalism needs shoring up with redistributive measures, others (and their corrupt cronies) regard capitalism in the same way that looters regard a burning supermarket: they don���t want to put the fire out, but just grab what they can before the roof collapses.

May 21, 2022

Stealing a living

Now I am retired, I can safely make a confession: for years, I was stealing a living.

I say so because the general financial advice any retail investor needs is actually very simple:

- Minimize taxes and charges. Avoid expensive fund manager fees. Don���t trade very much. Make full use of Isa and Sipp allowances.

- Make the power of compounding work for you, not against you. Start investing as early as you can. And remember that fund managers��� fees compound horribly over time; an extra half percentage point in annual fees can easily add up to over ��2000 for every ��10,000 invested over twenty years.

- Diversify sensibly. Hold equities for growth, and non-equity assets (which might just be cash or your earning potential) to spread risk.

- Invest regularly, via monthly direct debits. The habit of savings is important.

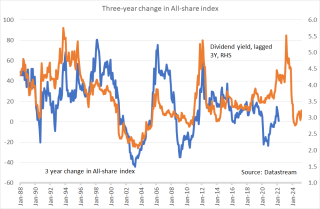

Granted, we can finesse this. History suggests we can use market timing; equity returns have been partly predictable by consumption-wealth ratios, the dividend yield, ten-month moving averages or simply the time of year. And two types of stock have beaten the market on average over the long-term: defensives and momentum: yes, most stock market anomalies are illusory (pdf) or short-lived, but not these two.

But retail investors don���t need these add-ons, not least because we���ve no guarantee that past relationships will continue to exist. Many people can safely invest in tracker funds and cash and get on with their lives. You needn���t bother with portfolio optimization. It can���t be done. Simple (pdf) diversification works. Satisficing is the best we can do.

Everything useful that needs saying about investing can thus be written in a few words. Beyond this, there are sharply diminishing returns and I suspect even negative ones. Which is why I say I was stealing a living.

And so too have been thousands of finance professionals:

- Equity analysts. ���corporate growth rates are random��� concluded Paul Geroski in one study (pdf). ���There is no persistence in long-term earnings growth beyond chance��� found Chen Karceski and Lakonishok in another (pdf). ���Firm growth is characterized by a predominant stochastic element, making it difficult to predict��� concluded Alex Coad in another survey. All of which means that, insofar as equity analysts are paid to forecast earnings (and in fairness they do other things) they are getting money for nothing. The big price falls we���ve seen recently in Netflix and Peloton (along others) shows the dangers in relying upon forecasts for earnings growth.

- Economic forecasters. Prakash Loungani has shown that these have consistently failed to predict recessions around the world: they are better at forecasting GDP growth in normal times, but that���s when we don���t really need forecasts. If you want to know the chances of recession, just look at the yield curve.

- Fund managers. These, said the Financial Conduct Authority in a recent report, ���did not outperform their own benchmarks after fees.��� The ���vast majority��� of them, said David Blake and colleagues in another ���were not simply unlucky, they were genuinely unskilled.��� Such findings corroborate evidence which we���ve had for years (pdf) in the US (pdf). Granted, there���s some evidence fund managers can pick stocks, but the benefits of this are dissipated by their need to hold more shares to reduce liquidity risk, or by their poor selling strategies.

Many people in finance, then, are simply quacks, snake oil salesmen.

I use the analogy for a reason. Quacks and snake oil salesmen thrived for decades: the market does not always weed out charlatans. Our latter-day snake oil salesmen prosper because they use similar techniques to their 19th century counterparts, described (pdf) brilliantly by Werner Troesken. They use product differentiation (such as the launch of new funds, be it small cap ones in the 80s, TMT ones in the 90s or ESG ones today); exploit wishful thinking and the public���s ignorance or distrust of experts; and they rely upon people not distinguishing between skill and luck.

The analogies between the finance and patent medicine industries aren���t perfect, however. One difference is that the finance industry is less competitive. Thomas Philippon (pdf) and Guillaume Bazot (pdf) have shown that the costs of financial intermediation (such as fund managers��� fees or spreads between borrowing and lending rates) haven���t changed for decades. The IT revolution has done nothing to lower costs for customers.

Huge swathes of the finance industry are therefore failing their customers. This is not because of mis-selling or crime. It happens in the legal everyday operation of the industry. Adair Turner was bang right to describe much of the finance industry as "socially useless".

Which is true in another way ��� the financing of business. For every ��1 banks have lent to UK manufacturing companies they have lent ��34 in personal mortgages. And in 2019 (the last normal year before the pandemic) banks��� net lending to non-financial companies was just ��11.5bn compared to household savings of ��72.2bn. The idea that banks use household savings to finance business isn���t just wrong in theory (savings don���t create loans): it is wrong as a matter of numbers. Banks are property lenders with a casino sideline, rather than financiers of industry.

The financial system, then, does not serve its customers well.

There���s another way in which this is true ��� financial innovation.

As Robert Shiller has shown (pdf) ��� based on Arrow and Debreu���s work in the 50s - financial products could in theory protect individuals from big economic risks. If we could trade securities which were claims on GDP or occupational earnings, people worried about or exposed to downturns could protect themselves by going short. This is especially useful because, given the impossibility of predicting recessions, monetary and fiscal policies are not sufficient protection.

In fact, though, we don���t get such useful innovations ��� or at least not on the scale we need. Instead, we get scams and gimmicks such as ICOs or NFTs.

There���s a reason for this. The innovation we get depends upon whether innovators can capture a sufficient fraction of their benefits. They can do so for (say) NFTs, but not for Shiller-type products.

It���s tempting to infer from this that we have a financial system which is not fit for purpose. Such an inference is wrong. It is superbly well-equipped for purpose ��� if that purpose is to funnel wealth from clients (and wider society) to itself.

You might think this claim is a radical one. Maybe, maybe not. It is, however, one that is rooted in wholly conventional economics. You don���t need heterodox thinking to challenge the existing order.

May 9, 2022

House prices: who wins, who loses

I grow my own kale and never buy any from the shops. If the price of kale rises, do I therefore win or lose?

The answer is: neither. On the one hand, I could profit if I were to sell the kale I grow. But on the other, the cost of eating my own kale ��� the money I would make if I were to sell it ��� has also risen. Net, I���m neither better or worse off.

Some of you might not care very much about the kale-growers of Rutland. What���s true of kale, though, is true of something many of you do care about ��� house prices.

Just as I am self-sufficient in kale, so I���m self-sufficient in housing. As an owner-occupier, I���m a supplier and buyer of housing services in equal amounts. What���s true of kale prices, therefore, also applies to house prices. A rise in my house price would make me richer if I were to sell. But to the same extent it increases the cost of me occupying the house ��� the money I���d make if I were to sell. Net, it���s a wash. For me, house prices are not wealth. And what���s true for me is true for many other owner-occupiers. As Mervyn King said (pdf) back in 1998:

A rise in house prices leads not only to an increase in wealth but also to an increase in the cost of housing services. Or, to put it another way, if the price of your home goes up, you will not be able to spend more on other things if you wish to carry on living in your home.

(See also this pdf by Willem Buiter)

Who, then, does gain from higher house prices?

Plenty of people. Those who are sellers, or who expect to be. These include owner-occupiers planning on trading down, say because their house is part of their pension, or landlords looking to cash out. It also includes people expecting bequests of their parents��� or grandparents��� houses.

But of course, if prospective sellers benefit from higher prices prospective buyers lose.

High house prices, then, are a transfer not so much from young to old ��� many of us oldsters don���t give a damn about house prices and many more shouldn���t ��� but from many young people to a subset of owners and inheritors.

But is it a zero-sum transfer, or a positive- or negative-sum one?

In some cases, it���s positive-sum. Rising house prices also benefit those planning on using their house as collateral to borrow for consumption, home improvements, to start a business or to use home equity release schemes to top up their pension. These are winners without corresponding losers. In fact, to the extent that higher house prices encourage business start-ups (and there���s evidence (pdf) at least from the US that they do), everyone gains from increased aggregate supply and competition.

On the other hand, though, it can be negative-sum. Insofar as they increase household debt, higher house prices increase economies��� vulnerability (pdf) to financial crises. And there are several channels through which they depress productivity. In increasing commuting times and distances workers are more likely to become stressed and absent. Insofar as they encourage construction booms they divert economic activity into less productive sectors of the economy. If people are spending huge sums on housing costs ��� either mortgages or rent ��� they���ve less to spend in dynamic sectors or upon the goods and services supplied by new companies, all of which deters entrepreneurship. And high and rising prices divert potential entrepreneurs towards rentier activities such as landlordism whilst also channelling savings away from business and towards property.

Net, rising house prices are a bad thing.

Boris Johnson, however, has other priorities. He said recently that if the government does more to help people with the cost of living ���that will mean that people���s interest rates on their mortgages go up, the cost of borrowing goes up, and we face an even worse problem���.

There���s a germ of truth here. Anything that supports aggregate demand would tend to raise inflation (relative to what it would otherwise be) and hence raise interest rates.

But why would this be ���an even worse problem��� than hunger and fuel poverty?

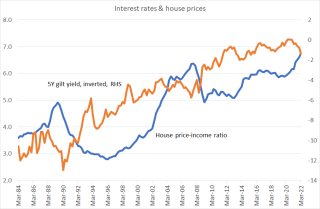

My chart shows why. It shows that the rise in house prices relative to incomes since the 1990s has been closely associated with the long-term downtrend in interest rates. This is because houses are an asset, and the price of an asset is the discounted value of future incomes ��� be they rent or the rent you save by being an owner-occupier. Lower interest rates mean a lower discount rate and hence a higher asset price. There is therefore widespread agreement that house prices depend heavily (pdf) upon interest rates. And indeed, on the rare occasions when interest rates have risen (such as in the late 80s or mid-00s) house prices subsequently fell soon after.

Which is why the Tories are so scared of rising interest rates. It���s because they would lower house prices. Which is nasty for that minority who do depend upon high and rising prices, such as those hoping for a bequest or landlords. It is these ��� whom Phil rightly describes as the most backward, uncompetitive and socially regressive sections of capital - who are Johnson���s client base.

And their interests collide with those of three other groups. One is those who most need help with cost of living. In refusing to support these for fear of higher interest rates, the government is sacrificing them to protect landlords and those hoping for a big inheritance. The second group are renters and wannabe buyers. And the third group comprises many entrepreneurs and potential entrepreneurs ��� those whose businesses are being stymied their potential customers are handing cash over to utility companies and landlords instead of spending it with them. If we had an intelligent opposition, it would be trying to form a coalition of these interest groups.

Of course, house prices are a deeply political issue. But let���s be clear what the division of interests is. It is not young versus old, but rentiers versus the rest of us.

April 3, 2022

Privatized Keynesianism

Everybody���s talking about the cost of living crisis. Which poses the question: why are we not therefore also talking about recession?

The Treasury���s regular survey shows that private sector forecasts for real GDP growth this year range between 3.3 and 5.7 per cent, with a median of 4.1%, and the OBR is forecasting 3.8% growth. How can we reconcile this with Bank of England Governor Andrew Bailey���s talk of ���an historic shock to real incomes��� and with the OBR and private sector forecasters predicting a fall in households��� real incomes?

It���s certainly not because fiscal policy will support demand. It won���t. It will tighten this year: the OBR foresees cyclically adjusted net borrowing falling from 6.1% of GDP in 2021-22 to 4.4% in 2022-23 thanks to higher NICs and real-terms cuts to departmental spending.

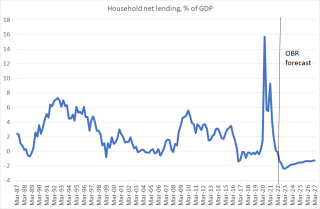

Instead, forecasters expect something else to rescue the economy ��� household borrowing.

The OBR foresees the household savings ratio falling to 3.1% in 2023, its lowest rate in over 60 years. And it expects households to be net borrowers throughout the next five years, something unprecedented since current data began in 1987.

In part, this is because it expects us to run down some of the savings we built up during the pandemic. But of course, not all of us did build up savings: those on low incomes or who lost their jobs never got the chance to do so. The OBR expects these to borrow more. Granted, it doesn���t see aggregate debt rising much more than post-tax incomes over the next five years, but the debt is likely to be concentrated among those in poor financial health to start with.

What the OBR expects is, therefore, a form of what Colin Crouch called privatized Keynesianism (pdf). Government borrowing won���t support demand much, but ��� it believes - private sector borrowing will.

In three respects, however, this is inferior to conventional Keynesianism.

One is that we cannot wholly rely upon it happening. Perhaps the pandemic has thrust us into more frugal habits, such as eating and drinking at home with friends rather than going to pubs and restaurants. Perhaps the fear of Covid will keep us out of shops and pubs. Perhaps we���ll fear that the squeeze on real incomes will be long-lasting ��� and if our permanent income falls, so too should our spending. And of course, some of us are credit-constrained: who���ll lend to a single parent on a zero-hours contract?

In this respect, the prospects for privatized Keynesianism are less good than they were in the first iteration of that project, the 1980s. Back then household borrowing rose strongly, supporting demand. But things were different then. Years of credit regulation meant that households began the 1980s with debt below desired levels. We cannot say the same today. And borrowing then was based on those who kept their jobs being (reasonably) optimistic about their future incomes. But there���s a difference between borrowing because you expect your incomes to rise, and borrowing to buy necessities ��� one of them being banks��� willingness to lend to you.

Secondly, privatized Keynesianism is simply less efficient as a way of transferring real resources from the future to the present. Even after the recent rise in gilt yields, the government can borrow at real yields of less than two per cent ��� which means that for every ��100 it borrows for 20 years it will have to repay only ��65. Households, however, have no such luxury. Even the best personal loan rates are only marginally negative in real terms ��� and of course not everybody is creditworthy enough to get these. Somebody who responds to the income squeeze by cutting their pension contributions will miss out on a real return of probably 3-5% a year. And of course, there are those who���ll have to resort to loan sharks at usurious rates.

If you believe that government borrowing imposes a burden upon future generations, you much think this is even more true of household dis-saving. Affluent households who cut their pension contributions or bank balances will leave less to their children. And stressed-out lower income parents will be less able to buy books, musical instruments or school trips for their children, thus impairing their education and future earnings.

Which takes us to a third problem. Privatized Keynesianism increases financial fragility. Households who have run down their savings or built up debts are more likely to cut their spending when made unemployed, thereby exacerbating the next recession. Banks who extend their balance sheets are more likely to restrict credit in bad times. And of course, even if there are no adverse macro-level effects of increased debt, individuals who have run up debts face stress, uncertainty and violent threats from loan-sharks.

All of which poses the question: why would anyone prefer privatized to government Keynesianism?

A good answer is that if you really believe that households will borrow a lot so that demand grows well then conventional Keynesianism is not only unnecessary but dangerous, as it would add to inflation.

But there are less good answers. One is that the government is making a fetish of the public finances, and is ignoring the fact that private borrowing to support demand is more dangerous than public borrowing.

Even nastier than this, however, is another possibility. In our stagnant economy, there are few profitable opportunities, so the government needs to create some. And one way of doing so is to create conditions in which households are forced to borrow at high rates. We have a government for loan sharks.

March 24, 2022

Inflation: the real problem

Everybody says we have an inflation problem. Everybody is wrong. What we have is a relative price problem.

The biggest reason for high inflation is that petrol prices and utility bills are soaring ��� up by 22.3% and 23.1% respectively in the last 12 months, contributing 1.5 percentage points to February���s 6.2% CPI inflation.

Imagine, though, that prices in the rest of the economy were flat, so that inflation were below its 2% target. Would everything be OK? No. We would still be handing over a bigger chunk of our incomes to monopolistic utility companies and to foreign despots.

What we have is a relative price problem. And this is a real problem in the sense that it���s a transfer of real resources.

This echoes an old phenomenon, described by David Ricardo in 1815. As the economy and population grow, he said, farmers would have to cultivate less and less fertile land to meet demand for food. That, he said, meant that food prices would rise over time. Which would squeeze real incomes and thus eventually kill off growth. It would also mean, he said, that owners of the best land could charge higher rents and prices, thus transferring income from renters to themselves.

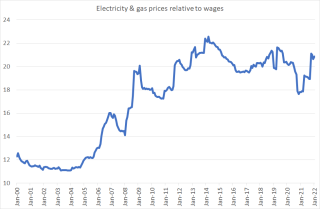

Ricardo���s theory was wrong for food; thanks to trade and technical progress (two similar things) their prices fell after he wrote. But the gist of it was right. We are transferring a growing portion of our incomes to a different type of rentier ��� owners of utility companies and gas and oil reserves*. And this is not merely a short-term problem: in the last 20 years, gas and electricity bills have doubled relative to wages**.

This threatens to have the same effect that Ricardo predicted. If we are handing all our cash over to utility companies, we���ve nothing left to spend in more dynamic sectors. And so growth will slow. This is a version of Baumol���s cost disease.

The OBR thinks we���ll escape this fate this year because households will respond to the squeeze on incomes by saving less and borrowing more: it foresees the savings ratio dropping to a 60-year low. Even if this happens this year (which is questionable) it still leaves us with a longer-term problem. Stagnant productivity, a rising relative price of services (not least of which are government services) and the fading away of the effect of cheap imports from China all threaten to continue to squeeze real incomes. If fuel and utility costs continue their long-term uptrend, the squeeze will only be worse.

So, what���s the solution?

We should accelerate decarbonization. As Eric Lonergan and Corinne Sawers point out, this requires more than tax changes. It requires a greater availability of alternatives to carbon-based fuels and greater ease in switching to them.

There���s also a case for nationalizing utilities and oil companies so that their rents are socialized and could be recycled back to us. This would prevent the growth-depressing transfer of real resources that Ricardo feared.

Neither of these, however, fully solve the problem. As long as productivity is stagnant, so too will be real incomes. Which means that any big change in relative prices where demand is inelastic will cut someone���s real income.

Which brings us back to what all sensible economists have been saying for years ��� that our fundamental problem is a lack of productivity growth.

* And not just these: Ricardo's theory also applies to prime commercial and residential land.

** The course of oil prices in is trickier. Although these are much higher now relative to consumer prices than they were at the start of the century, they are much lower than they were in 1980.

March 20, 2022

The politics of abstraction

There���s a link between two of the more absurd events of the weekend: David Cameron���s boasting of volunteering at a food bank; and Natalie Elphicke���s attempt to join a protest against P&O���s mass sackings.

Both are trying to repair the damage they themselves have done. Acute poverty, and hence the need for food banks, is the direct result of Cameron���s own austerity policies. And P&O can only replace its staff with agency workers because Elphicke and her fellow Tory MPs voted against Barry Gardiner���s bill to outlaw the practice.

What we have, then, is an apparent absurdity ��� people objecting to the foreseeable consequences of their own actions. How can this happen?

Part of the story is that most people have a strong urge to feel they are doing the right thing. We do not smirk like Dick Dastardly as we take pleasure in our evil schemes but instead perform intellectual contortions to satisfy ourselves that we are in fact the goodies; this is one form of self-serving bias. It���s this instinct that has given rise to ESG (environmental, social and governance) investing with all its greenwashing and hypocrisies.

In itself, however, this instinct need not have led Cameron and Elphicke to act as they did. In many minds instead it leads only to arguments that austerity or voting for bad bosses was necessary for the greater good.

So why didn���t Cameron and Elphicke pursue this line instead? Here���s a theory: their ideology blinds them to the fact that policies hurt real people. Politics isn���t merely about finding positive-sum solutions; it���s about choosing who to throw under the bus.

But they don���t want to face this fact. Instead, for them, politics is about abstractions independent of real lived experience. It���s about what plays well in focus groups; what appeals to the media; what does well on ���the grid��� (to use a 90s metaphor). And politics goes no further than that.

So for example, ���cutting red tape��� is a sign that you oppose big government rather than are content to risk people burning to death in high-rise buildings. In the same way, austerity or voting against firing and rehiring are merely symbolic acts, signals that one is on the right side, rather than acts with consequences.

This echoes Joe Stalin. "If only one man dies of hunger, that is a tragedy. If millions die, that���s only statistics" he said. And by statistics he meant not the fact that statistics is the plural of anecdote but that they are just another abstract debating point to be manipulated on the Posh Twats Talk Shit shows that pass for politics programmes. Hence Elphicke���s discombobulation when confronted with the unavoidable fact that actions do have consequences, that politics hurts real people.

Johnson gave us a clear example of this politics of abstraction yesterday. His likening of Ukrainians to Brexit voters is of course too far beneath contempt to deserve comment. What���s also revealing, though, is this:

When the British people voted for Brexit, in such large, large numbers, I don���t believe it was because they were remotely hostile to foreigners. It���s because they wanted to be free to do things differently.

This misses two things. One is that Brexiters have so far failed to tell me what I am free to do now that I wasn���t in 2016. The other is that this government is actually suppressing freedom by seeking to criminalize protest and is reducing freedom even in the narrowest Thatcherite terms by raising taxes to their highest level in decades. Johnson���s love of freedom is a pure abstraction, divorced from his actual actions.

But here���s the thing. In treating politics as a reified activity separate from lived experience, the Tories are not alone. In their book Managing Britannia Robert Protherough and John Pick describe how modern management ���deals largely in symbols and abstractions��� ��� which is how oil companies can claim to be green.

And some critics of the Tories do a similar thing. Some are more agitated about Johnson���s possible receipt of a fixed penalty notice than they were about the mass social murder of austerity. The image of hypocrisy matters to them more than the reality of tens of thousands of deaths.

It���s tempting to see all this as vindication of T.S. Eliot���s claim that ���humankind cannot bear very much reality.��� But I���m not so sure this is all there is. Tories have not always tried to deny the consequences of their policies. Thatcher called miners ���the enemy within���; she didn���t try to join them on the picket line as Elphicke would have. And Norman Lamont called unemployment a price ���well worth paying��� and never felt the need to do a stint in a Job Centre.

So what changed? A bit of me thinks the Tories retreat from reality is because the truths of capitalism ��� stagnation, corruption and inefficiency ��� are no longer ones that can be uttered in public. But it might instead simply be that they have become vacuous idiots.

March 2, 2022

The same old mistakes

War, wrote Carl von Clausewitz, ���is merely the continuation of politics with other means.��� Which implies that the mistakes made in thinking about war will be similar to those made when thinking about domestic policy. This is especially true of those, such as Dan Hodges, calling for a no-fly zone in Ukraine.

Of course, Mr Hodges is a squit who is best ignored. What���s significant is that his call reflects two widespread errors.

Error one is that you must base policy not upon what you hope will happen, nor even upon what you expect to happen, but upon the range of possible outcomes. For example, in the IC, I tell my readers to hold a decent proportion of cash to protect against the possibility not just of losses on equities, but of falls in equity and bond prices at the same time. Imposing a no-fly zone in Ukraine would require shooting down Russian planes which would risk triggering all-out war with Russia. There���s no point dismissing this risk: you don���t know enough about Putin���s mind to do so. What matters is avoiding it. And to their credit, Boris Johnson and Ben Wallace seem to be doing so.

You might think this principle is an obvious one. It���s not. Brexit was based in part upon wishful thinking to the neglect of the downside risk that the EU would prove a tough negotiator. A post-Brexit trade deal would be "one of the easiest in human history" said Liam Fox. ���The day after we vote to leave, we hold all the cards and we can choose the path we want��� said Michael Gove. Subsequent events have not necessarily vindicated such optimism.

Ditto fiscal austerity after 2010. There might have been a case for this if the world economy were strong and the UK sector sufficiently dynamic to take up the slack created by weak government demand. But they weren���t. Sensible fiscal policy would have heeded the risk of this. When in 2012 Vince Cable tried to excuse the UK���s weak growth by pointing to the euro crisis, he was actually drawing attention to how bad policy was, because it was not founded upon the distribution of probabilities.

Ditto Iraq. The lack of post-occupation planning was due in part to wishful thinking rather than to a consideration of probabilities, one of which was that the country would sink into chaos.

It���s not just government policy that can go terribly wrong by failing to consider probability distributions. So too can corporate policy. RBS���s takeover of ABN Amro ��� which contributed greatly to the financial crisis ��� owed much to Fred Goodwin thinking he could reap synergies to the neglect of evidence that takeovers have a high probability of poor returns for the bidder.

There is, though, a second error in calls for a no-fly zone which has a counterpart in domestic policy. It���s what I���ve called the pawn mistake ��� of regarding the objects of your policy as pawns who will do your bidding, rather than strategic actors with their own agency and objectives.

The first question to ask of a no-fly zone is: how would Putin react? The answer to which is: possibly not as we would wish him to.

Again, you might think this is obvious. But again, it���s not been obvious to our rulers. In 2019 Digby Jones tweeted:

Hey Mr Tusk. Those who pushed for Brexit did have a plan but it required your lot not to bully the UK, for Remoaners & the Establishment not to sabotage the wish of the majority & for Jezza���s mob not to play tribal party politics with a major National issue.

His discombobulation reflects the assumption of (some) Brexiteers that the EU would do the UK���s bidding, that they would defer to a posh English accent. But the EU wasn���t a mere pawn.

Brexiteers aren���t the only culprits here, though. One reason why target culture has not improved productivity (in the private as well as public sectors) as much as its advocates hoped is that workers are not mere pawns but strategic actors. So they meet targets not by doing more or better work but by teaching to the test; distorting clinical priorities; producing unreplicable academic research; or cooking the books.

I suspect one reason why the Labour right has discovered an appetite for party unity ��� which it oddly didn���t have in 2015-19 ��� is an anger that the little people aren���t merely passive fund-raisers and door-knockers but have the temerity to have thoughts of their own. They don���t see, and still less appreciate, that people are agents not pawns.

Again, though, it���s not just in politics that we see this error. We see it too in stock markets. One of the best-attested anomalies is that of IPO underperformance: newly-floated stocks on average do badly in their first three years on the market. A big reason for this lies in investors��� failure to think strategically. They don���t ask: if this is such a great company why are its owners, who know more about it than anyone else, so keen to sell?

Calls for a no-fly zone are therefore indeed the continuation of politics in that they are the continuation of widespread errors.

But here���s the thing. These errors should be widely known by now: if a twat in Rutland knows them, so should anybody with political influence. The fact that they seem not to be tells us something significant ��� that a good portion of politics has become divorced from serious thinking about policy and unable to learn from past mistakes.

Chris Dillow's Blog

- Chris Dillow's profile

- 2 followers