Chris Dillow's Blog, page 9

February 14, 2022

How to shrink the state

Steve Barclay, the Prime Minister���s chief of staff, says he wants to ���restore a smaller state���. This is mere virtue signalling.

For one thing, the Tories��� actual behaviour shows no appetite for a smaller state. Quite the opposite. They oppose drug legalization; have authorized the security services to commit crime; and are seeking to suppress protest.

But there���s something else. It���s that if you are serious about cutting government spending as a share of GDP you need much more than libertarian instincts. You need a strong economy.

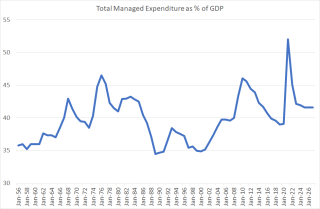

My chart shows the point, showing total managed expenditure as a share of GDP since 1955-56.

It���s not easy to discern from this alone any great political changes. Yes, the share of government spending in GDP rose in the 1960s as social democracy became more entrenched, and also grew during the second New Labour administration from 2001 to 2005. But it also rose in the early years of the Thatcher administration ��� from 41.5 per cent in 1978-79 to 43.3 per cent in 1982-83. And it fell in the first few years of the New Labour government. Few, though, would argue that Thatcher believed in bigger government and Brown in smaller.

Instead, what stands out more are economic booms and slumps. Government spending rose as a share of GDP after the oil shock of 1973; during the recessions of the early 80s and 90s; during the financial crisis of 2007-09; and during the pandemic. And it fell during the booms of the late 80s and late 90s.

The state of the economy is a stronger determinant of the share of public spending in GDP than is the ideology of the government.

We can put this more formally. The OBR has estimates of the output gap going back to 1972-73. Between then and 2019-20 (that is, just before the pandemic), the correlation between that gap and the share of TME in GDP was minus 0.4. A weak economy means a higher share of government spending, and a stronger economy a smaller share.

By contrast, the relationship between the share of TME in GDP and dummy variable measuring whether the Tories or Labour are in government is statistically insignificant. Which tells us that the state of the economy matters more for the size of government than does which party is in government.

Now, you might think that the output gap is a bad measure. I���d agree. But another measure tells a similar story. If we look at five-year changes in real GDP and in the share of public spending in GDP we also see a negative correlation. For the TME share it was minus 0.43 between 1955-56 and 2019-20. And for the share of current spending in GDP it has been even stronger, at minus 0.56. If we look only at the post-1973 period ��� that is, to exclude the Golden Age of strong growth, the correlations have been stronger, at minus 0.61 for the share of TME in GDP and minus 0.63 for the share of current spending. And these figures exclude the pandemic year, and so understate the correlation for the whole period.

I���m not very numerate ��� though am more so than many MPs ��� but I do know that a fraction comprises two parts, a numerator and a denominator. You can reduce a fraction therefore not by reducing the numerator but by increasing the denominator. And history tells us that this has been the main way in which state spending shrinks as a portion of GDP.

If you are serious about shrinking the state, you need to do more than wave Hayek and Nozick at us (or, Gawd help us, Ayn Rand). What you also need is stronger economic growth.

Which brings us to a problem. The Tories cannot deliver this, for four reasons:

- Brexit red tape is reducing trade and depressing GDP. Free trade agreements with other countries are unlikely to offset this damage.

- They are still austerians, as we are seeing with Sunak and Johnson���s promise to raise NICs even during a cost of living crisis. The OBR foresees cyclically-adjusted net borrowing falling from 8.3 per cent of GDP this fiscal year to 1.5 per cent by 2026-27. That means weaker growth and hence a still-high share of public spending in GDP: the OBR forecasts that even in 2026-27 TME will be over 41 per cent of GDP, much higher than it was during the New Labour years before the financial crisis.

- Tories electoral interests militate against promoting growth, even if they knew how to do so. A stagnant economy fosters reactionary illiberal attitudes and hence support for their culture wars.

- Tory supporters��� and donors��� interests are antagonistic to faster growth. Policies to promote growth would hurt rentiers ��� such as shifting incomes from incomes to property, liberalizing planning laws or promoting competition. And higher trend growth would probably entail higher real interest rates, thus hurting rentiers still more.

If you are sincere about wanting to shrink government spending as a share of GDP, you cannot support the Tory party as it currently exists. Given the party���s lurch towards illiberalism, however, you cannot support Labour either.

February 12, 2022

The puzzle of media influence

It���s sometimes said that Johnson is in trouble because his erstwhile supporters in the media have turned against him. I���ve no interest in that claim, but it raises an overlooked issue: why does the media still have so much influence despite collapsing newspaper circulation?

For example, since 1997 the Daily Mail���s circulation has fallen from 2.3m to under one million, and the Guardian���s from 428,000 to 109,000. And although the Sun, Telegraph and Times no longer publicise their circulation, data from 2019-20 show falls of over 50%. Of course, digital readership has risen, but it���s not clear that this sustains their political influence: you can read the Mail���s sidebar of shame without succumbing to the paper���s politics.

Such collapses in circulation, however, have not been matched by a decline in their influence. Nobody says the media is only one-third as powerful as it was in the 90s, although it would be if its influence had matched its sales.

Although it is easy to overstate this power ��� people can be right-wing idiots without the help of the Sun or Mail ��� it still exists. Two facts tell us this. One is the age-voting gradient. Older people consume much more legacy media (including the BBC) than others, and they vote right. In the 2019 election over-65s split 62%-18% Tories to Labour, whilst 25-34 year-olds went 23% Tory-55% Labour. The other is that In Liverpool, where the Sun is not sold, the Labour (and Remain) vote has been bigger than in otherwise comparable areas. As Mic Wright says:

Despite declining revenues and readership, the British press (and the broadcast media that hews closely to the agenda it sets) does not simply report the news, it creates it.

Why is this?

One explanation is that the legacy media still has a big comparative advantage. Granted, it is mostly useless at describing longer-term social changes and emergent processes or at scrutinizing legislation: think of the comparative lack of coverage of the police bill. But it is better than other sources at breaking Westminster bubble stories, such as those about the Downing Street parties. This fact alone gives it some influence over party politics.

But there might be more to it than this.

One possibility is that a belief in the power of the press is self-fulfilling. As Duncan Robinson says:

[The tabloids] maintain influence because they shape elite opinion - among ministers and the BBC - not because they speak for the people, who no longer buy them.

The media are like the Wizard of Oz, possessing power because people believe in that power. If a politician believes he can be made or broken by Murdoch or the Mail, he���ll stay in their good books and so they will indeed have power.

Secondly, political careers have become shorter. David Cameron, for example, spent only 15 years in parliament: Thatcher and Wilson were MPs for longer than that before becoming PM. And several New Labour MPs who would now have accumulated to the experience to be ���big beasts��� have long left national politics, such as David Miliband, Ruth Kelly, Ed Balls or James Purnell. With parliamentary careers truncated, politicians can no longer build reputations through campaigning within the party (the old ���rubber chicken��� circuit) or through diligent backbench work. Which means they need quicker routes to prominence, and the media offer these.

Thirdly, people don���t see politics as a discrete and separate activity with its own distinct criteria of excellence and failure. In fact, many politicians don���t even realize what the purpose of politics is ��� the solution or amelioration of collective action problems. Instead, we watch politics in the way our nans used to watch the wrestling, cheering the good guys whilst trying to hit the baddies with their handbags.

This gives influence to the dumbed-down media. Back in 2018 John Humphrys said of Brexit ��� on one of the BBC���s ���flagship��� programmes - that this is ���all getting a wee bit technical and I���m sure people are fed up to the back teeth of all this talk of stuff most of us don���t clearly understand.��� This revealed journalists��� disdain for policy analysis if favour of the ���drama��� of Westminster shenanigans. If we think of politics as being about policy, such attitudes would render the media irrelevant. But with so many regarding politics as cheap entertainment, so it retains influence.

Fourthly, party membership has fallen. Labour has less than 500,000 members, only half as many as in the mid-1950s, whilst the Tories have around 200,000 compared to a peak of almost three million. This means people are much less likely to hear political news and opinion from doorstep canvassers or (more importantly I suspect) from friends and work colleagues. The media���s influence has thus increased simply because an alternate source of influence has diminished. This is all the more true because people have limited attention. Few want to actively seek out information and ideas, preferring to consume it passively.

Fifthly, there���s an ageing population. Older people are not just more likely to buy a newspaper (pdf) than young ones, but are also more likely to watch TV news: 72% of viewers of BBC One���s news are aged 55 or more. And they are cut off from the effects of being in work ��� not only from material concerns about wages, working conditions and the state of the economy but also the influence of conversations with co-workers. This means media influence is greater, because a countervailing influence has disappeared ��� a fact especially true for the many older people who live lonely lives.

The ageing population less rooted in material conditions whilst being big media consumers makes it easier for the media to push the agenda of fanatics and hobbyists, be it Brexit or the culture wars. It might be no accident, therefore, that the salience of culture war issues has increased with the number of retired people.

I say all this for a simple reason. It���s common enough to bemoan the influence of the media ��� and reasonable, given that insofar as this influence exists it is largely pernicious. What we should ask, though, is: what socio-economic factors sustain this influence? The answer, I fear, is not pretty.

February 6, 2022

Strategic impotence

You all know a man who pretends to be unable to do basic household chores in order to avoid them and escape to his man-cave whilst his partner does the work: you might even be that man. This is a more widespread tactic than is generally appreciated. We can call it strategic impotence ��� using a claim to be unable to do something as means of pursuing one���s advantage or cementing privilege.

We���ve seen an example this week when Rishi Sunak claimed to be powerless on the face of rising energy prices:

No British chancellor can stop what is happening in Asia or stop a nuclear power station going offline in Germany

This is true as far as it goes. Which isn���t very far. As Sir Dieter Helm has pointed out, Chancellors could and should have spent recent years investing in greater energy capacity. And France is raising electricity prices by just 4%, in part by squeezing the profits of state-owned EDF. Sunak���s professed lack of control over prices is thus an example of strategic impotence.

There are countless others.

- Legal defences. Claiming a lack of responsibility is a common plea of innocence or mitigation. One of the most famous uses of this was that of Ernest Saunders who, having been imprisoned for insider trading, was released early from prison after suffering dementia only to make a miraculous recovery.

- Corporate websites. Making it difficult for customers to cancel their subscriptions looks like bad design, but it���s a way of maintaining income.

- Lady Macbeth. Lord Ashcroft���s claim that Carrie Johnson is to blame for her husband���s misdeeds denies his agency and responsibility. This follows a tradition of imputing Lady Macbeth-type spouses to powerful men in an attempt to deflect blame from them.

- Playing the victim. The right claim to be victims of ���wokesters��� who are suppressing free speech. This serves to efface the fact that it is the Tories who are the enemies of freedom, for example in criminalizing protest. In the same way, their claim to be victims of ���EU bullying��� is used to escape their own incompetent negotiations.

- Refusing pay rises. Bosses who reject requests for better pay and conditions on the grounds that they can���t afford them are often telling the truth. But sometimes they are not. "My hands are tied" is the slogan of the strategically impotent.

- Admitting forecasting errors. David Viniar, Goldman Sachs CFO, said during the financial crisis that ���we were seeing things that were 25-standard deviation moves (pdf), several days in a row���. And in 2012 Vince Cable justified fiscal austerity in the face of low growth by pointing to the spillover effect of the euro crisis: ���no one was expecting that the situation across the channel would deteriorate as much as it has done.��� It���s true that nobody can accurately foretell the economic future, but claims such as Viniar���s and Cable���s are inadequate. A policy that is based upon a forecast of a particular outcome is wrong: policy must be based instead upon the range of possible outcomes. These are therefore examples of claims to impotence being used to avoid guilt and maintain power.

Perhaps the most important example of strategic impotence, however, lies in the public finances. The idea that we cannot afford increased public spending because of the state of the public finances is of course plain wrong. At current long-term interest rates, governments can borrow tens of billions and repay less in real terms. As Maynard Keynes said, ���anything we can actually do, we can afford���. The constraint on public spending is a lack of sufficient labour and materials, not of money. Denying this fact is strategic impotence. The claim that we cannot do something is used to hide the fact that we choose not to do so.

(We should not here that the BBC has been complicit in this lie, as we saw in Kuenssberg���s talk of government borrowing being ���absolutely maxxed out���. Which touches on another example of strategic impotence: the BBC���s claim to be impartial and a mere reporter of events is used to efface the fact that it influences public opinion.)

In speaking of strategic impotence I am of course echoing two closely related ideas. One is Lindsey McGoey���s idea of strategic ignorance, whereby a lack of knowledge ��� sometimes genuine, sometimes not ��� is mobilized for political purposes. The other is capitalist realism, the idea that alternatives to capitalism have become unimaginable. That could be an emergent process (as much ideology is) whereas I���m thinking of instances where strategic impotence is used as a conscious strategy.

Strategic impotence, however, has a flipside. At the same time as the ruling elite deny their own power and agency, they overstate the agency of the poor. The government���s threat to withdraw benefits from people who fail to seek jobs for which they are unqualified overstates the ability of people to find work. It echoes Tebbit���s claim that the jobless could find jobs if only they got on their bike. In the same spirit, Kirstie Allsopp says young people can afford houses if only they stop going to the gym or move to where there are no jobs. (Yes, there is a contradiction there, but hey ho). That attributes to them more agency than they actually have.

The ruling class and its shills want to deny the obvious fact that there are huge inequalities of power and influence. Strategic impotence is one of the tricks it uses to do this.

January 22, 2022

Power, not prices

We���re heading for a cost of living crisis because of big price rises for essential items such as gas and food. Everybody knows this. Which is unfortunate, because it���s not quite true.

Of course, I don���t deny that prices are rising. They are. What���s doubtful is that they are the sole cause of falling real incomes.

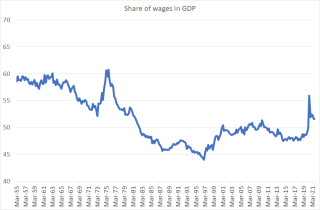

Simple statistics tell us this. Since quarterly data began in 1955 fluctuations in annual inflation (measured by the consumption deflator) have explained only 4.2% of the variation in annual growth in real households��� incomes; for longer-term changes such as three or five-year ones the explanatory power is even lower. This tells us that rising prices alone have been only a tiny cause of changes in real incomes.

What���s more, our period of highest inflation actually saw real household incomes do well. Consumer prices more than tripled during the 1970s, in part because the oil price rose by a factor of ten. But real households��� disposable incomes then grew by an average of 3.4 per cent a year ��� more than twice as much as they grew in the ten years before the pandemic, a period of low inflation.

Inflation on its own, therefore, is not a sufficient explanation of falling real incomes. Sometimes, as in 2016, real household incomes fall when inflation is low. And sometimes they rise when inflation is high, as in the 70s.

So, what does explain variations in real incomes?

Power, that���s what. There are two big differences between now and the 70s.

One is that back then many workers had the bargaining power to extract pay rises to maintain their real incomes in the face of rising prices. In the mid-70s the wage share in GDP rose sharply. It was capitalists and shareholders who suffered a crisis, not working households.

The other was that government borrowing rose markedly, which helped support incomes. Because that increased debt was devalued by inflation (in those na��ve days before index-linked gilts) this meant there was in effect a transfer of real resources from gilt investors to other households.

Today, things are different. Except in a few industries, workers don���t have the power to protect real wages that they had for a while in the 70s. ONS data show that average weekly wages rose 4.2% in the year to November and that median monthly pay rose 5.3% in the year to December. Both measures fall short of CPI inflation.

What���s more, fiscal policy is being tightened. The OBR foresees cyclically-adjusted net borrowing falling by 4.4 percentage points of GDP in 2022-23. Higher NICs, the cut in Universal Credit and public sector pay restraint are all taking real incomes from households.

Real household incomes are not, then, falling solely because of inflation. They���re falling because people lack the market or political power to protect themselves from external shocks in the way they did in the 70s. Back in the 70s, working people were portrayed as greedy knaves; today they are seen as pawns, victims lacking agency (to borrowing Julian Le Grand���s terminology (pdf)). There���s a reason for this change.

A fall in some people���s real incomes at a time when GDP is growing ��� as is likely this year ��� is a transfer of real resources, from those without power to those with it. Inflation is a means (often unintended) whereby this transfer occurs. It is not the sole cause of it.

The ���classical dichotomy��� ��� the idea that real variables affect only things and monetary variables (such as prices) only monetary ones ��� is sometimes wrong. But not always; it usefully reminds us to think about real factors, not just monetary ones.

Those who attribute the cost of living crisis to inflation are therefore wrong. But their error is an old one. It���s what Georg Lukacs called reification, the process whereby:

A relation between people takes on the character of a thing and thus acquires a ���phantom objectivity���, an autonomy that seems so strictly rational and all-embracing as to conceal every trace of its fundamental nature: the relation between people.

It���s what Marx called commodity fetishism ��� the way in which relations between people assume ���the fantastic form of a relation between things.���

Even well-meaning talk of inflation, therefore, is ideological: it effaces a brute fact about capitalism, that some people have more power than others.

January 13, 2022

How to commit fraud

It is fitting that Boris Johnson���s premiership should be in doubt so soon after Elizabeth Holmes has been found guilty of defrauding investors, because both show us how easily people are fooled.

Inspired by them, here are some tips for any would-be con artist.

Exploit wishful thinking. Experiments by Guy Mayraz have shown just how easy it is to induce this. People want to believe there���s been a great medical breakthrough, or that an obscure mining company has discovered huge mineral deposits, or that they���ve met ���the one��� who won���t cheat on them.

Ms Holmes preyed on this: people wanted to believe there was a new Steve Jobs, and the wish was father to the belief. Similarly, Johnson���s supporters in 2019 thought you could get Brexit done by sunny optimism rather than hard bargaining. And, writes Robert Hutton, ministers are now defending him in the ���hope that, when Johnson is finally removed from office, the stink won���t linger on them or their party.���

FOMO is your friend. This is clearly the case for Prime Ministers or would-be PMs: MPs will support you in the hope of winning office themselves, and journalists will do so for fear of being frozen out and denied scoops. But it also worked for Ms Holmes. Private equity investors not wanting to miss the next unicorn pile into start-ups, sometimes without adequate research. Fear of missing out drive stock market bubbles, and it also enables fraud.

Be glamorous. ���Investors are attracted to stocks that have emotional ���glitter������ says Alok Kumar. We���re also attracted to people who glitter. We���re apt to trust good-looking ones even if they don���t deserve it ��� a fact Ms Holmes used on Henry Kissinger.

Of course, Johnson doesn���t have physical attraction on his side. But his schtick of raffish charm, bumbling good humour and optimism appeals to some. You���d rather go for a drink with him than Theresa May, even if you would have to buy it yourself.

Like attracts like. Affinity frauds are good business, because it���s easier to win the trust of people who think you are one of them. Bernie Madoff, for example, sold his Ponzi scheme to people like himself - affluent, respectable-looking Jews.

Similarly, Ms Holmes appealed to the rich because she was from a ���good family���. One investor ���says he thought Holmes would come by medical talent naturally because her grandparents had their name on a hospital.���

Hence the power of the ���Boris��� brand. Calling him by his first name creates an impression that he���s your mate. And you trust your mates, don���t you?

Have a story. Vanity Fair reports:

Holmes also paid indefatigable attention to her company���s story, its ���narrative.��� Theranos was not simply endeavoring to make a product that sold off the shelves and lined investors��� pockets; rather, it was attempting something far more poignant. In interviews, Holmes reiterated that Theranos���s proprietary technology could take a pinprick���s worth of blood, extracted from the tip of a finger, instead of intravenously, and test for hundreds of diseases���a remarkable innovation that was going to save millions of lives and, in a phrase she often repeated, ���change the world.

Narratives matter. People believe them more than they should. And better still, as Robert Shiller shows in Narrative Economics, some of them go viral. People will do your work for you, by repeating your story.

Johnson also has used this trick. ���Get Brexit done��� and ���levelling up��� are stories ��� albeit ones we have to fill in ourselves.

Exploit deference. We have, wrote Adam Smith, a ���disposition to admire, and almost to worship, the rich and the powerful.��� You don���t have to be very rich or powerful to get such admiration. Some experiments in 1968 showed that drivers were less likely (pdf) to honk their horns in impatience at expensive cars than at cheap ones, for example.

This gives the fraudster his chance. If you pretend to be a bank official or policeman, somebody will hand over their account details to you out of deference.

And it���s part of the secret of Holmes and Johnson: journalists at least defer to bosses and Prime Ministers. The corridors of power turn venality into virtue and stupidity to wisdom.

Be different. In a superlative paper (pdf) the late Werner Troesken showed how snake oil salesmen thrived for centuries in part by differentiating their products. Disenchantment with some quack remedies therefore merely fuelled demand for others.

Ms Holmes exploited this. Merely by being a woman she stood out in male-dominated Silicon Valley.

And it���s part of Johnson���s success too. Tom McTague has written:

Johnson is nothing like the other prime ministers I���ve covered. Tony Blair and David Cameron were polished and formidable. Gordon Brown and Theresa May were rigid, fearful, cautious. Johnson might as well be another species.

That���s his appeal. In differentiating himself from both the cold fish Theresa May and from the technocratic style of New Labour, people disillusioned with both of those thus turned to him.

Now, in writing all this I���m not suggesting that you become fraudsters. For one thing, it���s difficult to pull off these tricks, especially if you are from the wrong background. For another fraudsters, like other businessmen, need not just personal skills but the right opportunities too. And for another, I've missed out some necessary advice - how to have an exit strategy and avoid getting caught.

Instead, what I���m trying to do is solve a puzzle raised in the Times recently by Matthew Parris. He describes how ���scores of individuals��� have had their reputations ruined because ���they got themselves mixed up with a superlative confidence trickster���. What he doesn���t do is say why so many people fell for Johnson. It���s not because they are stupid. Isaac Newton and Jonathan Swift both lost money in the South Sea bubble which tells us that even brilliant men can fall for cons. Instead, it���s because there are so many ways to trick even intelligent people.

January 10, 2022

Against work

The FT has a nice piece on the rise of the anti-work movement in the US, which encourages people to cut down on their paid employment: although different, this movement has something in common with the ���financial independence, retire early��� community.

All this contrasts with the Labour party since the 1990s, most of whose leaders ��� Sir Kier Starmer included ��� have valorized ���hard-working families���*.

By this, they don���t mean people who work hard tending their allotments, practicing guitar or painting Warhammer figures. Instead, what Labour values ��� and the FIRE and anti-work movements do not ��� is paid employment.

There is, of course, a very long tradition on the anti-work side. Ancient Greek intellectuals despised manual workers because they could not devote their time to cultivating the mind ��� a tradition that inspired the ideal of the gentleman amateur in England.

Adam Smith had this in mind when he described the debilitating effects of the division of labour:

The man whose whole life is spent in performing a few simple operations, of which the effects are perhaps always the same, or very nearly the same, has no occasion to exert his understanding or to exercise his invention in finding out expedients for removing difficulties which never occur. He naturally loses, therefore, the habit of such exertion, and generally becomes as stupid and ignorant as it is possible for a human creature to become. The torpor of his mind renders him not only incapable of relishing or bearing a part in any rational conversation, but of conceiving any generous, noble, or tender sentiment, and consequently of forming any just judgment concerning many even of the ordinary duties of private life. Of the great and extensive interests of his country he is altogether incapable of judging.

It's not just manual work that has such effects. John Malesic describes how it leads to burnout. And John Danaher complains that employment ���colonizes��� our lives by dominating our mental space. Those contestants on Christmas University Challenge illustrate his point: ���distinguished careers��� (a malefaction I have been spared) can lead to an ignorance of everything outside one���s work.

Which aren���t the only problems. As Danaher says, ���work is a source of freedom-undermining domination���. This isn���t only true in the many cases of egregious tyranny. As Martin Hagglund describes in his superlative This Life, even benign work steals that important scarce resource, time.

There is nothing ���natural��� about any of this. In his Stone Age Economics Marshall Sahlins shows how stone age men typically worked only a few hours a day. ���Work as we know it is a modern invention��� wrote Andre Gorz in his Critique of Economic Reason. The ethic of hard work, he wrote, ���was a revolution, a subversion of the way of life��� of pre-industrial times ��� a revolution, as Stephen Marglin showed, imposed by capitalist hierarchy. E.P Thompson has described (pdf) how it arose ��� over generations - from ���the division of labour; the supervision of labour; fines; bells and clocks; money incentives; preachings and schoolings; [and] the suppression of fairs and sports.���

Hard work, then, is at best like physical courage ��� a virtue only in unpleasant circumstances.

Which has led to ideas such as Aaron Bastani���s fully automated luxury communism, a society in which commonly-owned technologies free us from drudge work.

Bastani���s terminology and inspiration might be Marxist, but you certainly don���t need to be a Marxist to buy into this ideal. In fact, historically, the great Liberals have espoused it too. John Stuart Mill wrote in 1848:

I am not charmed with the ideal of life held out by those who think that the normal state of human beings is that of struggling to get on; that the trampling, crushing, elbowing, and treading on each other���s heels, which form the existing type of social life, are the most desirable lot of human kind, or anything but the disagreeable symptoms of one of the phases of industrial progress���.It is only in the backward countries of the world that increased production is still an important object

In this tradition, Bertrand Russell wrote In Praise of Idleness, in which he looked forward to a short working week encouraging arts and science and ���simple happiness���. And Keynes famously thought (pdf) that a 15-hour working week would be ���quite enough to satisfy the old Adam in most of us!���

All of which poses the question. If the case against work is so strong, why has the Labour party for years valorized hard work so much?

There is a good reason. The transition from a world of hard work and accumulation to one of degrowth is difficult enough for individuals ��� which is why so many of us postpone retirement ��� and harder still for societies: it requires enormous social and cultural change.

But there are also bad ones. One is Labour���s fear of being seen to be on the side of benefit recipients. (There���s actually no evidence that it is, but evidence rarely plays a big role in party politics). Another is that politicians tend to be monomanic dullards, and they are sublimating that vision of life onto the rest of us. Also, social democratic politics requires economic activity to finance a big state: valorizing hard work and economic growth are alternatives to demanding massive redistribution.

And then, I fear, there is capitalist realism. It is too easy to see capitalist jobs ��� with their alienation, unfreedom, burnout and thwarting of our potential ��� as unavoidable. But in fact they might be, as Mill thought, merely ���disagreeable symptoms of one of the phases of industrial progress���.

* Ironically, the one leader least prone to use that clich�� ��� Jeremy Corbyn ��� was the one who more than the others actually won the votes of working people. Which might be a neat example of John Kay���s obliquity.

December 30, 2021

Class, sympathy & solidarity

The conviction of Ghislaine Maxwell has promoted some sympathetic headlines. Both ABC and CBS write of her ���fall from grace��� and the BBC of her ���downfall���. All of which reflects Rachel Johnson���s attitude, that ���it���s hard not to pity��� her.

In part, there���s an echo of a sentiment we���ve largely lost ��� a tendency to sympathize with the criminal. Vast amounts of country music express this: The Banks of the Ohio, San Quentin, Folsom Prison Blues or Pancho and Lefty to name but a few. Tom Jones version of Green Green Grass of Home, remember, was one of the best-selling hits of the 1960s.

And there���s a reason for this pity. We don���t become criminals merely because we are irredeemable wrong���uns: to believe that is to commit a crass form of the fundamental attribution error. Instead, incentives, weakness of will, or peer pressure are all important causes. As David Friedman wrote:

A mugger is a mugger for the same reason I am an economist���because it is the most attractive alternative available to him.

Or as Iris Dement sang:

And I traveled to a prison; I saw my share of shattered dreams.

Were the tables slightly tilted I could be bound, they could be free.

Why not extend such thoughts to Ms Maxwell? She was born into and lived in a criminogenic environment.

But, but, but. The sympathy of headline writers is tightly circumscribed. They rarely speak of a downfall or fall from grace after working class people are convicted. Ms Johnson���s pity does not extend to them, and the BBC���s ���due impartiality��� does not apply in matters of class.

What���s going on here was pointed out by Adam Smith:

We frequently see the respectful attentions of the world more strongly directed towards the rich and the great, than towards the wise and the virtuous. We see frequently the vices and follies of the powerful much less despised than the poverty and weakness of the innocent.

This, he wrote, is because the wealth and comfort of the rich elicits not envy but sympathy:

When we consider the condition of the great, in those delusive colours in which the imagination is apt to paint it. it seems to be almost the abstract idea of a perfect and happy state���We feel, therefore, a peculiar sympathy with the satisfaction of those who are in it. We favour all their inclinations, and forward all their wishes. What pity, we think, that anything should spoil and corrupt so agreeable a situation!... Every calamity that befals them, every injury that is done them, excites in the breast of the spectator ten times more compassion and resentment than he would have felt, had the same things happened to other men.

Reactions to the conviction of Ms Maxwell fit this pattern.

But Smith���s reasoning helps explain something bigger and more powerful ��� of why there is more class solidarity among the rich than among the working class. We see this in several contexts. One minor but nevertheless revealing example is in the circle jerk of blue-tick columnists praising each other, as Justin Horton has documented. Another example is that right ���libertarians��� are relaxed about clampdowns upon migrants and protestors because these bear upon the poor and weak rather than the rich and the great.

More importantly, this helps explain the unity of the Tory party. Johnson has ��� at least until recently ��� retained support from erstwhile Thatcherites even though his ���fuck business��� attitude is the diametric opposite of hers. And the party has almost seamlessly shifted from a social liberalism that supported gay marriage to a confected war on wokesters.

Of course, such deference-based unity is imperfect. But it is much greater than we see on the left, where divisions are rife and where working class consciousness has never developed to the extent that early Marxists had hoped.

Those headlines about Ms Maxwell, then, are not trivial. They shed light upon one of the great strengths the ruling class has over the rest of us.

December 12, 2021

On purified identities

One of my favourite social thinkers of recent years is Richard Sennett. There���s one particular idea of his that deserves especial attention today ��� that of a purified identity.

Such an identity arises, he says, when:

The threat of being overwhelmed by difficult social interactions is dealt with by fixing a self-image in advance, by making oneself a fixed object rather than an open person liable to be touched by a social situation. (The Uses of Disorder, p6)

People with such identities ���create an aura of invulnerable, unemotional competence for themselves��� by screening out or devaluing evidence that conflicts with that self-image. For such people, wrote Sennett, dissonances are ���interpreted as less real than the consonances with what is known.��� There are numerous psychological mechanisms at work in this: the confirmation bias, strategic ignorance, Bayesian conservatism and so on.

This is what Janan Ganesh is getting at here:

It is, at bottom, an almost childlike craving for the world to have order and structure. It is an intolerance of ambiguity���.Life must answer to a system of thought.

You might think that although Sennett wrote all this in 1970 it applies to ���snowflakes��� today who are ���triggered��� by microaggressions, and so want to ���cancel��� them.

Maybe. But the phenomenon is much wider than that. Sennett gave the examples of people who choose career paths early in life and stick to them, or who believe in ���the one���, an idealized romantic partner who overshadows actual real imperfect lovers. We might add to this people whose musical tastes are fixed in their adolescence and never progress.

Such purified identities contrast with people who are more open to new experiences, more accepting of disorder and dissonance ��� who have, in Sennett���s words, ���the courage to be self-doubting and confused.���

What���s more, said Sennett, we don���t just fix a self-identity for ourselves. We also create purified identities of societies:

The image of the community is purified of all that might convey a feeling of difference, let alone conflict, in who ���we��� are. In this way the myth of community solidarity is a purification ritual. (The Uses of Disorder, p36)

In this sense, ���woke snowflakes��� and opponents of migrants have more in common that either would like to admit. Both are trying to screen out dissonant elements in an attempt to preserve a static purified identity. All nations are imagined communities, but many on the right see Britain (or is it England?) as one in which migrants or Muslims or the poor are less than fully typical members. Which is why the left has a problem with patriotism.

Saying this shows that the distinction between the fixed purified identity and the more open personality is orthogonal to the left-right divide. The city planning debates between Robert Moses and Jane Jacobs, for example, are better seen as between purified and open personality types than a left-right issue. And James Scott���s Seeing Like a State is an analysis of how rulers with purified identities try to impose their fixed rationalist plans onto complex societies whilst ignoring dissonant feedback from those societies which would complicate their visions. Yes, those plans are sometimes leftist (for example the Soviet collectivization of farms), but they are sometimes not ��� for example shock therapy or the Chicago Boys plans for the Chilean economy in the 70s.

Those political and economic pundits who go from one wrong prediction to another without any interval of self-doubt are other examples of the purified identity: we should contrast them to those who take dissonance, error and uncertainty more seriously, and ask about the sources and limits of predictability.

It's in this context that I get irritated when Marxists are accused of having a dogma. Yes, some do: Marxism is one of the many forms that a purified identity can take. But others of us are erratic Marxists, being self-doubting and more open to dissonant evidence. A good example of this were the analytical (pdf) Marxists of the 70s and 80s, who tried to reconcile Marxism with conventional social science. They had the exact opposite of a fixed, purified identity ��� and in fact in retrospect their mistake was to be too open, too sceptical of conventional Marxism.

By the same token, many centrists do have purified identities, being so closed to new evidence that they don���t realize it is no longer 1997.

There���s a sharp distinction between extremism and fanaticism. You can be a cool-headed sceptical extremist (I don���t use the word ���rational��� because nobody is wholly rational) or a fanatical centrist. The person with a purified identity can be found across the political spectrum, as can more open-minded types.

Now, this isn't to say there's a sharp distinction between purified identities and open personalities: they are two ends of a spectrum. And we can have purified identities in some respects but not others: I think I'm more fixed and dogmatic in my political views than in my day job, for example.

Purified identities are a mixed blessing. Zealotry and fanaticism ��� passion if you like ��� spur people to work long hours and thus succeed in their careers to a greater extent than can more open-minded people with a range of interests. This gives us great musicians, but it also gives us single-minded fanatical politicians: one reason I could never have gone into politics is that it takes too many evenings.

And even if such identities are good for our careers they might not be so great for our mental health. If you don���t embrace the dissonance between your conception of yourself and the world and reality ��� and accept imperfection - it can destroy you. This was brilliantly described in a great song by Dar Williams*. ���Once upon a time I had control and reined my soul in tight��� she sings, but this leads to suicidal thoughts until she abandons control:

Cause when you live in a world

Well it gets in to who you thought you'd be

And now I laugh at how the world changed me.

* Songs are sociological, psychological and philosophical documents, every bit as valid (if not more so) as academic research.

December 8, 2021

The decline of the impartial spectator

That video of Allegra Stratton laughing about a Downing Street Christmas party last year shows that the government is taking for fools those who observed the law ��� even to the point that it meant leaving relatives to die alone. There is indeed ���one law for us and another for them.���

Naturally, this has aroused widespread anger. As Adam Smith wrote, ���All men, even the most stupid and unthinking, abhor fraud, perfidy, and injustice, and delight to see them punished.���

This poses the question: what is the disease of which Stratton���s laughter is a symptom?

I ask because to someone formed in the 1980s the sight of a Tory showing contempt for the law is perplexing. Thatcher often and loudly proclaimed the importance of the rule of law; I can���t imagine her laughing about illegal parties in Downing Street. What we have here is another example of how today���s Tories are anti-Thatcherite.

Nor, I think, is it simply a matter of class difference. The Queen, famously, observed social distancing rules even during her husband���s funeral.

Instead, I want to suggest that this reflects something else, something found in Adam Smith.

We are, he wrote, naturally selfish: ���we are always so much more deeply affected by whatever concerns ourselves, than by whatever concerns other men.��� But, he said, this selfishness is restrained by an impartial spectator who lives within us ��� what others call conscience. It is this spectator who ���shows us the propriety of generosity and the deformity of injustice���, and who reminds us that if we act unjustly we will ���render ourselves the proper object of the contempt and indignation of our brethren.��� The fear of such contempt keeps us honest, thought Smith. And even if our misdeeds go undetected by others, this ���man within��� will give us an ���inward disgrace.���

D.D. Raphael summarized Smith���s theory thus:

The approval and disapproval of oneself that we call conscience is an effect of judgments made by spectators. Each of us judges others as a spectator. Each of us finds spectators judging him. We then come to judge our own conduct by imagining whether an impartial spectator would approve or disapprove of it (The Impartial Spectator p 34-5)

The fact that Stratton saw flagrant injustice as a matter for laughter rather than shame suggests that, within her, the impartial spectator is weak.

And not just in her. One purpose of the spectator, said Smith, was to remind us that ���we value ourselves too much and other people too little.��� But this over-valuation ��� what Smith called self-love ��� is evident in others: in Johnson attempting to place himself above the law; in the Luckhurst���s contempt for their customers at Durham University*; in Rees-Mogg thinking the party was a laughing matter; or in Geoffrey Cox���s disregarding his constituents in favour of more lucrative employment. Indeed, we could see the cult of shareholder value and profit maximization as examples of capitalists generally acting in an anti-Smithian way, by ���prefer[ring] the interest of one to that of many.���

And of course, if one���s peer group are pursuing self-love there is no shame in doing so oneself. What Smith considered to be a great restraint upon selfishness ��� fear of disgrace in the eyes of others ��� thus disappears.

But why is the impartial spectator so weak? I���d suggest three reasons.

One is the decline of religion. One difference between the Queen and Johnson is that she is religious, and has thereby acquired a greater sense of duty and (a Smithian word) propriety.

A second force is the rise of a perceived meritocracy. When he coined this word in 1958, Michael Young meant it as a warning:

If the rich and powerful were encouraged by the general culture to believe that they fully deserved all they had, how arrogant they could become, and, if they were convinced it was all for the common good, how ruthless in pursuing their own advantage. (The Rise of the Meritocracy, pxvi)

You might think that Stratton and her like have little merit. But that���s not the point. They think they have, and so become ���insufferably smug��� as Young predicted.

A third factor is that recent decades have seen an significant form of increased social distancing. For a long time, the ruling class was dominated by men who had done military service and so come into close contact with working class men ��� an experience which reminded them of their own good fortune and taught them respect for that class. For them, the ���man within��� at least occasionally spoke with the voice of a working-class soldier. The Times��� obituary of Lord Carrington wrote:

He found himself sleeping in a hole beneath his tank with his four crew who came from poor backgrounds and had suffered hardship during the pre-war years. The experience shaped his politics, he said later. ���You could not have got a finer or better lot than they were. They deserved something better in the aftermath of the war.���

Something like this attitude persisted into my adult lifetime. In my first job most equity salesmen had army backgrounds and so were accustomed to working with the working class. It might be no accident that some of the Tories most critical of the government, such as Tobias Ellwood and Tom Tugendhat, are army men.

It���s not just the decline of military men that has weakened the impartial spectator, though. Perhaps the decline of manufacturing has had a similar effect. Factory bosses who encountered working class men on the shopfloor had some arrogance knocked out of them in a way that those who travel the private school-Oxbridge-professions escalator have not.

Of course, in saying all this I don���t mean to romanticize the past: exploitation and injustice have always been with us ��� although remember that inequality was lower in the post-war era than it is now. All I���m suggesting is that class arrogance and over-entitlement is more obvious and egregious now than it used to be.

Which is a counterweight to calls for Johnson to resign.

Maybe he should. But what we also need to be rid of is the mindset which he represents. And disposing of that is a much bigger task.

* Yes, customers. If you are charging ��9250 a year you are in the customer experience business, not the vigorous debate business.

November 27, 2021

The end of evidence-based centrism

One of centrists��� great conceits is that they are rational and moderate whist the left are fanatical ideologues. New Labour for example championed ���evidence-based policy-making���; Chris Leslie claimed (pdf) that they favour ���evidence not ideology���: and Steven Pinker has a BBC radio show telling us how to think better. Two recent interventions remind us that all this is self-serving nonsense.

One came from David Blunkett, who told the Today programme (2"57' in) that if we let in a few refugees, ���Nigel Farage might end up being Prime Minister���. That of course is mere speculation. What is evidence is that the UK does not get many asylum applications. There were only 29,456 in 2020, compared to 102,525 in Germany, 37,860 in Greece, 86,380 in Spain and 81,735 France. Lord Kerr is right: ���we are not the preferred destination in Europe��� for refugees. And given that the labour market impact of migration is tiny, we could easily accommodate more. The only ���migrant crisis��� is that of the migrants themselves: from the UK���s point of view, there is no crisis - only maladministration and cruel racism.

The other intervention came from Tony Blair. He claims that Labour ���is seen as being for everyone other than the hard-working families who feel their taxes aren���t spent on their priorities.���

Seen by whom? Not by hard-working families themselves. As Ben Walker has pointed out, in the 2019 general election Labour out-polled the Tories among working-age voters living in households with annual incomes below ��100,000. Labour���s problem is not with working people; it is with the retired.

Blair���s detachment from the evidence does not stop there. He goes on to claim that Labour must ���push the far left back to the margins��� and reject ���the old-fashioned statist view of the left���. This misses the fact that the ���far left��� is rejecting old-fashioned statism. It is fighting against the Tories assault upon civil liberties. And the ���defund the police��� slogan of Black Lives Matters, whatever its merits or not, is a profoundly anti-statist sentiment.

Of course, there is an authoritarian statist tradition on the left. But it is one of which Blair himself was a big part: New Labour created over 3000 new criminal offences and greatly increased the prison population, trends which the ���far left��� deplore.

There���s another odd thing about Blair���s comments. In attributing statism to the left, he omits to point out that its is the Tories who are increasing the size of the state: the OBR forecasts the tax burden rising to its highest level since the early 50s.

This increase will happen because of weak GDP growth, so public services must be financed by taxes rather than economic growth.

Blair, however, makes no mention of this long-term economic stagnation. Which is no idiosyncratic omission, but rather a consistent theme of centrists. Leslie made little reference to the financial crisis and its aftermath in his Centre Ground pamphlet, and the Independent Group/CUK omitted mention of it in its launch statement.

This blindspot matters enormously. Economic stagnation is a major cause of the current state of our politics. As Ben Friedman showed in 2006, hard economic times fuel reactionary politics ��� hence Brexit and anti-migrant bigotry. If Blair is sincere in wanting ���liberal, tolerant��� politics, he needs some way of kickstarting growth.

Here, though, it is the left that is evidence-based whilst the centre is trapped by outmoded ideology. Blair says Labour needs ���a new future-oriented policy agenda based on an understanding of how the world is changing.��� But this is just what Corbynite economic policies offered. They were based upon the recognition that the world has changed since the 90s, being characterised by stagnant productivity, negative real interest rates and the concentration of wealth and power among the 1%. By all means, argue with their remedies, but I don���t think you can charge the left with not seeing that the world is changing.

Which brings me to a curious phenomenon. Mainstream economists acknowledge the need to kickstart productivity; the role of fiscal policy in fighting stagnation; and the fact that immigration in economically benign. Blunkett and Blair seem much less alive to these facts. The political centre is now very different from the economic centre. And it is the left, more than some centrists, that is evidence-based.

Chris Dillow's Blog

- Chris Dillow's profile

- 2 followers