Chris Dillow's Blog, page 11

September 27, 2021

What Starmer misses: the C-word

One word is notably absent in Sir Keir Starmer���s recent essay ��� capitalism.

Our most successful politicians have had something to say about this ��� whether it be Thatcher���s belief that capitalism needed low inflation and weak unions if it were to thrive, or Blair���s belief that governments and people needed to adapt to capitalist forces of globalization. Starmer, however, has no such analysis.

For example, he notes that, ���entering the 2020s, Britain faced stagnant wages, vast inequality and the slowest growth in living standards since the second world war.��� But he attributes this solely to ���Tory failure���. Which is dubious. It omits the fact that slower growth in output and productivity ��� and the symptom thereof, lower real interest rates ��� are global phenomena. Larry Summers didn���t (re-) coin the phrase ���secular stagnation��� to describe bad policy in a single country.

Of course, we can debate the causes of this: falling profit rates, an ageing population, lack of monetizable innovations; depressed animal spirits as a legacy of the financial crisis; and so on. But Starmer seems unaware there���s even a debate. Which leads to this:

Business is a force for good in society, providing jobs, prosperity and wealth. But business has been let down by a Tory government.

But is it less of a force for good than it used to be? Stagnation, job polarization and deprofessionalization all mean that capitalism has become less good at providing jobs and prosperity for many people. To some extent, it is the Tory government that has been let down by business, not just vice versa.

Failing to ask this question leads to this:

A Labour government would provide a level playing field, a skilled workforce and a modern infrastructure, from transport to public services.

This is the politics of Prince: partying like it���s 1999. But capitalism has changed since then. We now need more than just good infrastructure and rules of the game to stimulate growth. Starmer shows no awareness of this possibility.

Which brings us to another omission. Starmer decries the nationalism and other ���identity-based politics in the Western world that has done immense damage to the progressive cause.��� But he fails to ask: why has such politics gained traction only in recent years? In the 90s and early 00s the Tories��� obsession with Europe led them into electoral oblivion. So why has it become so effective recently?

The answer ��� as regular readers will be bored of hearing ��� lies in Ben Friedman���s The Moral Consequences of Economic Growth. He shows that economic stagnation fuels illiberal nationalism, and sometimes worse. Populism is one more consequence of capitalist failure. If you don���t appreciate this, your critique of it is mere narcissistic moralizing: ���why can���t people be reasonable like ME?��� The cure for populism is economic growth. But if stagnation is due to capitalist failure as well as to Tory failure, this needs some kind of critique of capitalism ��� which Starmer lacks.

Here we run into another problem. Capitalism sets constraints upon what governments can do. These constraints operate in countless ways: lobbying; ownership of the media; offering ex-ministers well-paid jobs to incentivize them to behave whilst in government; controlling business confidence; emergently creating an ideology (pdf) which supports the existing order; and so on. These mechanisms mean that, as Pablo Torija Jimenez has shown, governments serve the interests of the 1%.

Good policies require much more than the goodwill and intellect of politicians. They require a material base, a particular set of class interests and balance of class power. We had this in the post-war era: a strong union movement and capitalist class that required a mass consumer market made full employment politically feasible. One challenge for social democratic politics is how to recreate such interests. In the absence of an analysis of capitalism, you cannot do this. Without it, though, your politics is just moralizing.

In lacking a critique of capitalism Starmer is actually more backward than capitalists themselves. One thing we���ve seen this year is the acquisition of companies such as Morrisons, Aggreko and Meggitt by private equity firms. This is happening in part because, as Michael Jensen famously pointed out, dispersed equity ownership is inappropriate for many firms ��� which is why we���ve seen a long-term decline in the numbers listed on stock markets.

But if capitalists themselves can ask the question of who should own assets, why shouldn���t politicians? It is quite possible that some forms of increased worker ownership will increase productivity, and so should be part of that suite of policies necessary to raise wages. This is not a terribly radical claim: it was part of the 1983 SDP manifesto. But it seems beyond Starmer. I fear his refusal to nationalize the big six energy companies is the product not of serious thought about the nature of ownership but rather an unthinking acceptance of the constraints set by capital.

Of course, I might be wrong here. Maybe capitalism is more dynamic than I believe and maybe it is less antagonistic to technocratic social democratic reforms. If you think I am wrong, though, you need to produce evidence and reasons. Which Starmer���s essay does not. It is one thing to be captured by capitalist interests. It is quite another not to even see the bars of your cage.

September 23, 2021

The death of free market ideology

Free market economics is dead as a political idea.

The government���s subsidy to CF Industries to ensure that it supplies a product that is (checks notes) soaring in price is just one of several examples of this. It has also introduced trade barriers within the UK, an almost unprecedent move for any developed nation in modern times. Even before the rise in National Insurance, it was planning on raising the share of taxes in GDP to what the OBR says would be ���its highest level since Roy Jenkins was Chancellor in the late 1960s.��� And you can interpret all the talk of ���levelling up��� (and it is all talk) as a renunciation of the free market idea that companies will relocate to areas where land and labour are relatively cheap.

All of this fits with Johnson���s ���fuck business��� remark; his renunciation of the European single market; and wilful increase in political uncertainty. What we have here is a flat rejection of Thatcherism.

Of course, markets are still a massive part of capitalism (and I suspect they should be a big part of post-capitalism too). But they have few defenders in government,

Which poses the question: why have we seen so great an intellectual counter-revolution?

It���s a tricky question because of an astonishing fact which demonstrates the emergent genius of the Tory party ��� that it has made this move without a protracted debate. Whereas the Labour party tears itself apart over much smaller differences, the Tories just get on with it without feeling any need for ideological consistency or introspection. As Sir Keir Starmer says, they have ���a remarkable ability to shed their skin.���

Although the Tories aren���t telling us why they���ve made so great a change, I���d suggest several possibilities.

One is the simple empirical fact, that free markets haven���t worked as billed. I don���t just mean that the pseudo-market in retail gas and electricity has failed. I���m thinking also of the financial crisis and the long stagnation in productivity. All show in different ways that markets don���t deliver stability and growth as much as hoped. Of course, free marketers have defences against these points ��� but the point is that they need defences, and are now on the back foot.

We can turn this around. In what sector is there a clear case for introducing more market forces? It���s not obvious. (No, healthcare isn���t one).

There���s a second reason, which we can derive from Jesse Norman���s admirable book, Adam Smith: what he thought and why it matters. Markets, he says, are not isolated technologies. Instead, they ���are sustained not merely by incentives of gain and loss, but by laws, institutions, norms and identities.���

If we have the right such norms and institutions, the self-interest of market actors will indeed promote the public interest. If not, though, we get rent-seeking, corruption and cronyism, as Jesse says:

Capitalism can encourage people to behave in socially productive or unproductive ways: to devote their energies to building homes or finding new tax loopholes; to developing life-saving drugs or running offshore sweatshops. It can stimulate fruitful investment, or the search for unwitting clients to be ripped off.

Latter-day free markets have, however, given us too much of the unproductive activities: fraud; mis-selling; cronyism and rentierism (pdf). Thatcher hoped a market society would give us men like her father; in fact it gave us ones like her son. Actually-existing free markets have not been embedded in the norms and institutions that would make them work in the public good. Which has, maybe unfairly, discredited the case for them.

Relatedly, one lesson of recent years is that capitalism requires a more extensive state than Thatcherites thought - not just to provide infrastructure and regulation but to provide automatic stabilizers and support for those ���left behind��� by globalization ��� a group which was never in the free marketeers��� original script.

Perhaps, though, there is something else. Tory support for market forces was strong when they were operating to enrich capitalists and hold down wages, but it has waned now that they are starting to raise wages, if only in a few sectors. Business owners whining about staff shortages are showing a fine sense of entitlement but not so keen a grasp of market economics. The attitude of many on the right to the free market reminds me of Corporal Jones: ���they don���t like it up ���em���.

Perhaps free market ideology was, for many, never a principle but only just one more weapon in the class war, a means of protecting what Tories really care about, which is the defence of private sector hierarchies.

September 19, 2021

Capitalism and the state

Greg Smith and Dehenna Davison write:

For many in left behind parts of the country, the reality is that the private sector is stifled by a bloated public sector that is almost Soviet-sized in some areas of the North.

This seems to me to be a case of confusing correlation and causality. The reason why the public sector accounts for such a big share of economic activity in some areas is that the private sector in those places is so weak.

In fact, I���d suggest that ��� for the economy as a whole ��� a bigger state can work to the benefit of capitalism.

My story here is not about the several mechanisms through which the rich (pdf) disproportionately influence government policy, nor about crony capitalism, corporate welfare, bank bailouts and implicit subsidies, important as all these are.

Instead, let���s start in a less likely place - with a paper (pdf) written by Robert Merton in 1969. He showed that the proportion of wealth an investor should devote to risky assets rather than safe ones such as cash or bonds could be described by a simple equation. This says the proportion should be equal to the expected annual return on risky assets over safe ones, divided by the product of the variance of risky returns and a coefficient of risk aversion.

Let���s put some numbers into this. One bit of standard theory (p20 of this pdf) predicts that the expected risk premium should be only two percentage points or even less. The standard deviation of a well-diversified equity portfolio is around 15% giving us a variance of 0.0225. And a reasonable estimate of the coefficient of risk aversion is around three. This give us a solution to Merton���s equation of 0.02/(0.0225x3) = 0.296. Less than a third of one���s wealth should therefore be in risky assets.

For many people, the weighting of equities should be even less. If you could lose your job in a recession, equities are especially risky for you because they too would fall when your earnings disappear. And if you regard housing as an asset (say because you are planning on trading down) it too could fall in a recession, when shares fall. Both risks point to a low equity weight.

What���s more, for many people the opportunity cost of holding equities is not cash or bond yields but rather paying off the mortgage or credit card bills, the interest rate on which is higher than that on cash. Yulia Merkoulova and Chris Veld point out that, for these people, the personal equity risk premium is very low or even negative. That can justify holding no equities at all.

Some standard economics therefore predicts that demand for equities should be very low indeed. Which suggests that stock market capitalization should be paltry.

So why isn���t it?

Enter the welfare state. The wealth in Merton���s equation means your total wealth. Wealth is merely capitalized income*. And income includes pension income. The state pension is therefore a big part of your wealth. At current annuity rates, the basic state pension is worth over ��170,000 for a 70-year-old. This means that, following the maths above, somebody with ��100,000 of other wealth should have not ��30,000 in equities but ��80,000.

The state pension thus boosts demand for equities. In giving us a safe income, it allows us to take financial risks we otherwise would not.

Of course, this is not the only way the welfare state supports the stock market. It acts as an automatic stabilizer, helping to mitigate recessions; this is especially important as policy-makers cannot predict recessions and so cannot always use monetary and fiscal policy to stabilize the economy. Such stabilization policy reduces the cyclicality of corporate earnings and also our background risks such as the cyclicality of or jobs and small businesses. On both counts, it raises demand for equities.

We often talk of tax incidence, the fact that taxes aren���t necessarily paid by the people they directly fall upon. But there is also benefit incidence: welfare benefits don���t benefit only those who receive them, but also those who own the businesses where those benefits get spent.

In fact, there���s a third historic benefit of the welfare state. In buying off discontent, it has reduced the threat of revolution which has also supported shares.

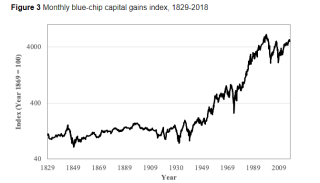

All of this explains a big fact ��� that stock markets in developed economies did best whilst the role of government in the economy was expanding. The UK market made no capital gains on average during the free market era of the 19th and early 20th century, but soared in the post-war era.

One reason for the famous equity premium puzzle (pdf) of Mehra and Prescott is that the riskiness of equities fell in the latter part of the 20th century and so share prices rose ��� as the threat of depression and political unrest fell. The larger welfare state is a big part of that story.

What Marx said in 1848 is therefore still valid: ���the executive of the modern state is nothing but a committee for managing the common affairs of the whole bourgeoisie.��� The state functions to support capitalism.

Of course, this is not to say that the current boundaries of the state are exactly those which are optimum for capitalism. Reasonable people can disagree on what these are: they might include a lot of social democracy.

Instead, my point is merely that there are many channels through which a big state can ��� and should! ��� sustain capitalism. Which is why few intelligent capitalists are minimal state purists, and perhaps why so many rightists have very comfortably abandoned the small state thinking of the 1980s.

* This is why wealth taxes should be redundant. If we���re measuring income properly (which the tax system does not), wealth taxes are just capitalised income taxes.

September 18, 2021

Cancel culture, & the death of classical liberalism

Most of us by now are bored with rightists complaining about cancel culture. But we shouldn���t be, because they show that the left has won an important battle about the meaning of liberty.

What I mean is that such complaints show that the right has abandoned a classical liberal conception of the term.

Let���s take Friedrich Hayek���s discussion of liberty. He defined this in negative terms, as the absence of coercion, where coercion is something which ���occurs when one man���s actions are made to serve another man���s will, not for his own but for the other���s purpose.���

But what exactly is and is not coercion? Here���s Hayek:

Coercion should be carefully distinguished from the conditions or terms on which our fellow men are willing to render us specific services or benefits���in a free society these mutual services are voluntary, and each can determine to whom he wants to render services and on what terms���If a hostess will invite me to her parties only if I conform to certain standards of conduct and dress, or my neighbour converse with me only if I observe conventional manners, this is certainly not coercion. (The Constitution of Liberty, p135-6).

In this sense, ���cancel culture��� is not coercion and not therefore a violation of freedom. If hostesses withdraw your invitation to speak to a student union because you don���t conform to their standards you are not being coerced. Nor are you if the Guardian withdraws the benefit of its employment from you - because in free society that is its choice.

Of course, the student hostesses and Guardian might be unwise or silly to ���cancel��� you. But on Hayek���s view of freedom they are not depriving you of your liberty. It is stupid of the Daily Telegraph to deny their readers the benefit of my wit and brilliance by not employing me as a columnist, but in doing so, it is not denying me freedom in Hayek���s sense.

But isn���t such no-platforming an example of what Mill called the tyranny of the majority?

Not for Hayek. For him, Mill���s complaint ���overstated the case for liberty���. Instead, for him social pressures could be a good thing:

There can be little question that these moral rules and conventions that possess less binding power than the law have an important role to perform and probably do as much to facilitate life in society as do the strict rules of law���Conventions and norms of social intercourse and individual conduct do not constitute a serious infringement of individual liberty but secure a certain minimum of uniformity of conduct that assists individual efforts more than it impedes them. (The Constitution of Liberty, p144-7)

This gives us a defence of ���woke��� social norms which forbid racism, homophobia or transphobia. Such norms ���facilitate life in society��� for people of colour, gays and trans folk by reducing the overt prejudice they used to suffer.

If the marketplace of ideas is to work properly, some thoughts must be cancelled. Just as a well-functioning market drives out shoddy goods, so it should also drive out bad ideas. ���Cancel culture��� is therefore an essential part of a market.

David Aaronovitch in the Times complains about self-censorship that arises from the fear ���of losing our livelihoods, disadvantaging our families or of not succeeding���. On a Hayekian view, however, such extra-legal penalties are not coercion and not ���a serious infringement of individual liberty���. They even serve a useful function: we want holocaust deniers, vax-opposers, racists and fruitloops to bite their tongue. If we didn���t self-censor, there would be a Hobbesian war of all against all. Do you really want to know my unself-censored opinions?

Again, you might object that our social norms are wrong. Fair enough. On a Hayekian reading, however, you cannot complain that they violate your liberty.

You might reply here, though, that Hayek���s conception of liberty was, as Martin Hagglund says in his superb This Life, merely ���formal��� and ���utterly impoverished��� as it is insufficient to provide substantive freedom.

Precisely.

Hayek had a reason for defining freedom this way. He wanted to show that coercion was something imposed by the state whilst the market and private sector were (except in circumstances he considered exceptional) ���a very Eden of the innate rights of man*.��� His idea of freedom was a way of promoting the market and a small state.

Those who complain about cancel culture being a threat to freedom, however, reject this project. If a few dippy students can violate your rights, mightn���t other private sector actors do so too in other ways? If employers limit your freedom by insisting you have particular political beliefs, don���t they also do so by insisting upon erratic or unsociable hours or low pay or bad working conditions? And if denying you a job for political reasons violates your freedom, isn���t your freedom also violated if the government, for political reasons, creates unemployment?

Once you think that ���cancel culture��� is anti-freedom, you are conceding the left���s claims that the private sector and employment relations are sources of unfreedom and that people should have not just political rights but substantive economic ones too, such as the right to well-paid work without oppressive employers.

We have, therefore, a lovely paradox ��� that classical liberalism in the Hayekian sense has been defeated not by the left but by the right itself.

So why did the right make this move? One possibility is that Hayek���s philosophy was only ever a cover for the pursuit of their material interests. In the 70s and 80s they regarded a smaller state and market forces as a means of asserting capital���s power over workers. Today, though, their concern is with protecting another type of inequality ��� the ability of old white men to spout off without challenge from hitherto marginalized people such as ethnic minorities, youngsters, or LGBTQI people. Conservatives��� main priority, as Corey Robin has argued, is to defend private sector hierarchies, and philosophy is subordinate to this end.

* That line is of course Marx���s.

September 10, 2021

The politics of abstraction

���Migrants will be turned back to France��� cheers the Daily Express ��� alongside a picture celebrating Emma Raducanu who is herself a migrant, the Canadian-born daughter of Chinese and Romanian parents.

Of course, an Express front page should normally be beneath our notice. This one, however, is significant as I suspect it embodies a widespread phenomenon in mainstream politics ��� the prioritizing of abstractions over real people.

The Express���s doublethink has happened because, for much of the right, ���migrants��� are not real people such as Ms Raducanu, or the parents of most of the England team which did so well in the summer���s Euros, or the perfectly nice people you meet at work and in shops. They are instead an abstraction, a phantom invoking a vague sense of the nation (another abstraction) losing control of its borders. This is why hostility to immigration has often been stronger in areas with fewer migrants rather than in cities with many of them. And it is why Priti Patel is threatening to turn back boats carrying migrants. So what if they drown? It���s not as if they are real people.

It���s not just in attitudes to immigration that we see this abstraction. The same has happened with Brexit. This was never about improving the living standards of real people but rather an appeal to abstractions such as national sovereignty and taking back control*.

This isn���t to say that the prioritizing of abstraction over ground truth is confined to the right. It���s not. In all its reports on the state of the public finances the BBC has not, as far as I know, ever interviewed a real person who has described convincingly how high government borrowing has worsened their own personal life. Fretting about the public finances is elevating an abstraction over the real lives of real people as it means devaluing the truth that austerity probably caused thousands of deaths.

Centrists are guilty of the same thing in another way. The ground truth is that the financial crisis taught us that capitalism is more unstable and less capable of generating growth in real wages than New Labour believed. This should have led to a rethinking of how to best achieve stability and rising living standards. But it didn���t. All the political centre has to offer is abstract waffle about electability. Hence (for example) Sir Keir Starmer���s inability to answer the simple question of how to pay for increased public spending on health and social care.

Older readers will detect a puzzle here. Back in the 90s New Labour spoke a lot about evidence-based policy-making. A generation later, however, what we have is abstraction-based policy-making. The story of how one gave way to the other needs to be told ��� and it will be one with no heroes but many villains.

* You might object here that in causing shortages of lorry drivers and hospitality workers Brexit is driving up wages. But this is true only of a minority of workers. And the price rises that are the counterpart of their pay rises mean cuts in real incomes for others ��� which is inevitable if higher pay isn���t accompanied by higher productivity. Sure enough, the ONS reports that real wages have actually fallen so far this year.

August 19, 2021

What's the mechanism?

The late great Andrew Glyn always asked: ���what���s the mechanism?��� The west���s abject failure in Afghanistan highlights both the importance of this question and the fact that too many policy-makers and influencers fail to give it sufficient attention.

President Biden says ���we did not go to Afghanistan to nation-build.��� Which poses Andrew���s question: what, then, was the mechanism through which the Taliban would be defeated? We know for certain that it was not the ones actually operating: western military strategy as it was implemented failed.

Exactly why this was the case is another matter, and one not relevant for my purpose*. Instead, my point is that the failure to satisfactorily ask and answer Andrew���s question was not confined to those supporting the military adventure in Afghanistan (or Iraq, or Libya). In fact, the failure is widespread.

For example, Anna Soubry still defends Tory-Lib Dem fiscal austerity, even though it caused (at the margin) the Brexit she detests. She is, even now, in denial of the mechanism that led to Brexit.

And then there are those centrists and Tories who now deplore Johnson���s corruption and incompetence but who failed to prevent it in 2019 by the only means possible ��� supporting Labour. In the 2019 election supporting Corbyn was the only means of preventing a Johnson premiership. Not doing so was to fail to ask: what���s the mechanism?

Much of the Labour right always fails to ask: through what mechanism can Labour win power if not (as a necessary but not sufficient condition) having a mass party to combat the effect of the mass media?

This failure, though, is not confined to airhead MPs and columnists. Even Nobel laureates are guilty of it. In Deaths of Despair Angus Deaton and Anne Case, having documented how American capitalism has been a force for mass social murder, write:

Capitalism needs to be better monitored and regulated.

They omit to ask: what���s the mechanism whereby this will be accomplished? There are many obstacles to it ��� one of which they themselves document: the fortunes spent on lobbying by big business. Humane, well-regulated capitalism requires a particular conjunction of class forces ��� one in which capitalists perceive that what���s good for workers is also good for them, and in which there is countervailing power (such as strong trades unions) to the tendency for capitalism to degenerate into cronyism. This conjunction existed in the post-war decades, but no longer does so. In its absence, the better-regulated capitalism urged by Deaton is as fantastically utopian as he believes socialism to be.

What we have here, then, is a widespread error. In not asking ���what���s the mechanism?��� we neglect the crucial importance of ground truth and implementation ��� the conditions of policy success or failure. Without these, however, policy-making is mere wishful thinking. This error of course is fuelled by a media bias: windbag opinion-mongers and Westminster gossips distract policy-makers and voters from facts on the ground, mechanisms and levers of power.

Which gives us a descent into crude identity politics. If you are not asking ���what is the mechanism by which we defeat the Taliban, or Johnson, or Brexit?��� you are left merely asserting your moral superiority without doing the hard work of thinking, discovering ground truth and ��� yes - making compromises. Which leaves you with little more than narcissism.

* I know nothing at all about foreign affairs, which it seems puts me on a par with the State Department and Foreign Office.

August 12, 2021

Ambition in capitalist society

Ambition, writes Lucy Kellaway, is both necessary and corrosive. She omits an important aspect here, which adds to its corrosiveness ��� class.

Class influences the level of ambition through two channels. One is that it distorts your awareness of opportunity. In Michael Apted���s superb TV series Up, the privately-educated Andrew knew (16'21" in) at the age of seven that he would go to Cambridge and become a lawyer. For the rest of us, our path to even modest success is not so pre-determined. I never thought about Oxford University until a teacher told me I could get in, and I never met anyone with a degree who wasn���t a teacher until I was in my 20s. If you���re not aware of the possibilities, you are less likely to be ambitious.

Another mechanism is that class sets the reference level of our income. When I realized that I would not have to worry about the leccy bill or becoming homeless, my ambition drained away. I was once one of those men brilliantly described by Adam Smith ��� a ���poor man's son, whom heaven in its anger has visited with ambition���. But I was lucky enough to have learned before my deathbed that ���wealth and greatness are mere trinkets of frivolous utility.��� If you���ve nobody you want to impress, money soon loses its point.

By contrast, those from posher backgrounds can feel failures if they don���t emulate their father���s success. For many of them, wealth and greatness are not of frivolous utility but are instead the benchmarks by which they compare themselves to their parents and contemporaries.

Both these mechanisms help explain the fact that people who have experienced poverty as children earn less as adults even controlling for education.

But they also tell us something else. What seems to be ambition is in fact fear ��� whether it be the fear of poverty or the fear of falling short of parental expectations.

In this context, Lucy���s advice that we must sometimes slough off ambition is a counsel of perfection. It���s fine for those of us who have paid off the mortgage and so no longer fear homelessness. Younger people facing high rents or mortgage payments cannot afford a lack of ambition, even if they are consumed by anger when it is thwarted.

Again, class matters. It limits your options.

Here, though, we must ask: ambitious for what? Alasdair MacIntyre distinguished between goods of excellence such as mastery of a craft and goods of effectiveness such as wealth and power. Sometimes, pursuit of one brings the other: achieving the good of excellence in football will bring with it wealth, fame and at least some influence: Marcus Rashford���s campaign against child poverty would have been less successful if he���d played for Stockport County.

In other cases, however, the two conflict. I doubt that the country���s most excellent journalists are the best-paid. Being an excellent academic won���t necessarily bring you the big money that comes from being university vice-chancellor. Prime Ministers aren���t always drawn from the most excellent MPs or ministers. And bosses aren���t necessarily the people who were best at the jobs their underlings do.

One component of that slippery term ���neoliberalism��� is, I suspect, the valorization of wealth, power and hierarchy over goods of excellence such as professional standards and craft skills.

Ambition for the goods of effectiveness can, though, be corrosive not just for individuals but for the economy. The man who is hungry for power and income will seek advancement even where he is not equipped for the job. And because employers (and voters) don���t always know (pdf) what they are doing they will sometimes hire that man. Hence the Dilbert principle, of which Gavin Williamson is perhaps only the most prominent of many examples.

Here, incentives matter. Where there are disproportionate rewards in terms of income, power and status for advancement, people will seek promotion even when they are unsuited for it. You might prefer to be a first-rate coder than a third rate boss, but if being that boss means a big pay rise you will go for it. And so talent will be misallocated. What we have here therefore is yet another way (of many) in which big inequalities are bad for the economy.

To see my point, imagine an egalitarian socialistic society in which inequalities of power and income are small; there is less social distance between rich and poor families; and whose culture celebrates the goods of excellence in professional and craft work more than those of effectiveness: it would be a MacIntyrean or Walzerian-type utopia.

In this society, there���d be less incentive to be Dilberts like Gavin Williamson because you could earn a decent living as a first-rate coder (or third-rate fireplace salesman) and so have less need to ���get on���. What John Stuart Mill called ���the trampling, crushing, elbowing, and treading on each other���s heels��� would diminish. And those who did ���get on��� would find their new roles, and the people they surround themselves with, less alien. So their ambition would not be the curse Smith thought it was. In these ways ambition would be less damaging to individuals and society.

You might think it hard to imagine such an environment. But then, as someone said, it is easier to imagine the end of the world than the end of capitalism.

August 7, 2021

Embracing Blair's legacy

Sir Keir Starmer wants Labour to ���embrace Tony Blair���s political legacy.��� Which poses the question: what is that legacy?

The usual response is merely an exchange of tribal grunts: ���Iraq��� versus ���won three elections���. The truth is more interesting.

Blair���s (and Brown���s) great genius was to see that social democracy had to adapt to new times. So, for example, his expansion of universities was a response to the increased wage inequality between graduates and non-graduates; tax credits were an attempt to tackle the prevalence of low pay caused in part by the weakness of trades unions and globalization; fiscal rules were a reaction to high real interest rates; and the granting of independence to the Bank of England represented the awareness that policy uncertainty had contributed to economic instability.

This was serious, sensible economics. And it contributed to some genuine achievements. New Labour cut child and pensioner poverty ��� it���s easy to forget that the latter was a big problem in the 90s ��� improved the NHS, and the expansion of universities helped to create a large progressive-liberal constituency.

But he also had grave faults. The biggest of these, I suspect, was his managerialism, his faith in the ability of bosses and governments to impose order from the top down. It was this that underpinned the target culture that demoralized public sector workers; the excessive deference to bosses and tolerance of the increased power and wealth of the 1%; the clampdown on migrants and benefit recipients; and the illiberalism that spawned thousands of new criminal offences.

I would argue that the Iraq war was a consequence of this. It arose from what James C. Scott has called ���high modernist ideology��� - too much confidence in the possibility of centralized knowledge (and the wisdom of leaders) which led to an under-valuing of ground truth.

Which brings me to why Starmer is dead right. Labour must embrace Blair���s legacy, in the sense that it must do what he did and adapt to new conditions. For example:

- In contrast to the 90s, real interest rates are now negative. This means tight fiscal policy is neither necessary nor ��� given the zero lower bound ��� desirable.

- In the 90s, Labour, like most economists, thought that a stable macroeconomic policy framework was sufficient to achieve stable economic growth. The financial crisis and subsequent productivity stagnation has shown this to be too optimistic. To promote growth, government must be more activist.

- Peter Mandelson was famously ���intensely relaxed��� about the very rich getting richer ��� a view consonant with Blair and Brown���s deference to business leaders. This can no longer be the case. It is very possible that the wealth- and power-grab of the top 1% is a cause of our poor economic performance.

- New Labour thought that education was the route to prosperity. Given the degradation of erstwhile ���middle class��� jobs and the unaffordability of housing, this is now doubtful.

- We have learned that there are limits what bosses and top-down management can do. New Labour���s excessive faith in these contributed to stagnant (pdf) public sector productivity and the financial crisis: bosses, it turned out, could stop banks going bust.

My personal view is that answers to these issues should entail more democratisation of economic life. But that's not my main point. It is instead that we should embrace Blair���s legacy by addressing the question he asked and answered: ���what does a modern social democracy look like?��� He rejected the idea that Labour could live in the world as it was twenty years previously. We should follow him in that rejection. In this sense, Blair had a wisdom which is wholly missing in his epigones.

August 4, 2021

The social mobility con

Strange as it might seem, we owe some thanks to Digby Jones ��� because he has reminded us that social mobility is a con.

Over the weekend he tweeted:

Enough! I can���t stand it anymore! Alex Scott spoils a good presentational job on the BBC Olympics Team with her very noticeable inability to pronounce her ���g���s at the end of a word. Competitors are NOT taking part, Alex, in the fencin, rowin, boxin, kayakin, weightliftin & swimmin.

Now, Ms Scott epitomizes the meritocratic ideal of someone coming from a poor background and succeeding through personal ability. She is a child of Thatcher:

it doesn't matter what your background is. I believe in merit, I belong to meritocracy, and I don't care two hoots what your background is. What I am concerned with is whatever your background, you have a chance to climb to the top.

Jones by contrast is telling us that background does matter. However brilliant a working class person might be, he will find a way of hating them.

Of course, not all of those in the establishment blurt out their hatred as crassly as Jones did. Just as many racists avoid using the N-word, so class haters are rarely so explicit. Nevertheless, his attitude is widespread. Here for example is Sajid Javid:

He describes going for an early interview at Rothschild and being confronted by a row of white men in pin-striped suits who asked him what his father did and where he went to school. ���The British merchant banks in those days would always go to the old school tie. If you didn���t go to the right country parties and spend the weekends in the right place you had got no connection,��� he says. ���I thought even if they offer me a job I���m never going to fit in.���

Everybody of obviously working class origin has experienced a degree of froideur in our encounters with posher colleagues, clients or bosses. With better men than Jones ��� and you can carve a better man than him from a turd ��� this will be subtle: those Rothschilds men were no doubt impeccably charming. But there is always a sense of being othered, a mutual awareness of difference ��� which, if you point it out, invites the accusation of chippiness. There is always, always, an undertow.

The best relationship the upwardly mobile can expect with posher colleagues is that of a trusted NCO with a good commissioned officer: it might be friendly and effective, but both sides always know there���s a difference.

One effect of all this is to depress social mobility. Sure, some people like Javid and myself can find well-paid jobs outside Rothschilds. But there are fewer places for us than there are for the posh boy.

And this can happen without overt class hatred of the sort displayed by Jones. It���s wholly reasonable for employers to want people they can trust or who look like they are safer bets. Like hires like ��� which diminishes the chances of people from working class backgrounds, or women, or ethnic minorities, or the disabled.

And those who overcome these barriers face another problem. We can never fully transcend the class of our birth. People from working-class backgrounds earn less than those from posh ones even when they have the same levels of experience and education. That���s because networks operate to their disadvantage.

Such networks diminish social opportunities as well as career ones. Men from poor homes are less likely to be married in later life (pdf), even controlling for their own incomes. This isolation, allied to the subtle stresses of living a life in unfamiliar surroundings is bad for our heath. As Michael Marmot has written:

Where you come from does matter for your health���Family background, measured as parents��� education and father���s social class, are related to risk of heart disease.

We know that immigrants tend to suffer from worse mental health than others. Perhaps migration across class borders has a similar effect.

All of which makes me think that Adam Smith had a point:

The poor man's son, whom heaven in its anger has visited with ambition���labours night and day to acquire talents superior to all his competitors. He endeavours next to bring those talents into public view, and with equal assiduity solicits every opportunity of employment. For this purpose he makes his court to all mankind; he serves those whom he hates, and is obsequious to those whom he despises. Through the whole of his life he pursues the idea of a certain artificial and elegant repose which he may never arrive at, for which he sacrifices a real tranquillity that is at all times in his power, and which, if in the extremity of old age he should at last attain to it, he will find to be in no respect preferable to that humble security and contentment which he had abandoned for it. It is then, in the last dregs of life, his body wasted with toil and diseases, his mind galled and ruffled by the memory of a thousand injuries and disappointments which he imagines he has met with from the injustice of his enemies, or from the perfidy and ingratitude of his friends, that he begins at last to find that wealth and greatness are mere trinkets of frivolous utility.

The point of all this is not to say that young working class people should not be ambitious. Instead, it is to suggest that social mobility is no substitute for genuine equality.

July 28, 2021

Cummings on complexity

One of the more interesting errors people sometimes make is to have a useful insight but draw incorrect inferences from it. So it is with this tweet from Dominic Cummings:

I get all sorts wrong all the time. And i don't *know* if Brexit is good or bad. Unlike remain twitter I think the world is highly complex & rapid error-correction of inevitable constant errors is almost the ultimate value.

It is wholly correct to stress that the world is complex and that errors of planning and policy are therefore inevitable. Politicians and journalists should be more aware of this.

I suspect, however, that Mr Cummings might not have drawn the right inferences from it..

Our reaction to complexity should not be to blunder around with a sledgehammer and then try to absolve ourselves by saying: ���who knows what would have happened? Things might have got broken anyway.���

In fact, there���s a longstanding principle which recommends the exact opposite. I���m thinking of Brainard conservatism (pdf). It says that in making policy central bankers should do less than models recommend. Think of adjusting the thermostat in a strange hotel room. You don���t turn it up a lot only then to boil and turn it down a lot: you���ll never get comfortable that way. Instead, you gently tweak the thing and wait and see what happens. Alan Blinder says this idea ���was never far from my mind��� when he was vice-chair of the Fed in the mid-90s.

As with most general principles, Brainard conservatism isn���t always correct: there are circumstances (pdf) where over-reaction is reasonable. It is, however, a specific application of an idea that surrounds us in business and everyday life ��� that uncertainty and complexity makes us do less than we otherwise would. We know, for example, that businesses respond to uncertainty (pdf) by reducing capital spending. In a complex world, irreversible investments are risky.

But of course, the Brexit referendum was like an irreversible investment. Whereas voters in general elections can correct their errors by changing their vote a few years later, they cannot do the same with a referendum.

Somebody who truly acknowledged complexity would not, therefore, have wanted a referendum in the first place.

And if they had, they wouldn���t have voted Leave. The effect of doing so was to introduce more complexity into the environment and so depress business investment.

Which is why I say Cummings might have drawn the wrong inference. For me, the existence of complexity was precisely a reason to oppose Brexit. As I wrote at the time:

Brexit is ���a very messy prospect, with years and years of negotiation lying ahead in a climate of uncertainty over the outcome���. Such uncertainty could dampen capital spending and investment in exporting activity.

There���s something else. Acknowledging complexity does not mean we should throw our hands up and say we know nothing. Of course, we cannot foretell the future. But we do know a few mechanisms. One of these is that trade frictions with the EU tend to reduce trade which in turn ��� via several channels - means less productivity. This tells us that Brexit will tend to make us poorer (pdf) over time, relative to what we would otherwise be.

Of course, in a complex world we can���t know how much poorer ��� and we���ll never know for sure even after the fact. But this poses the question: what plausible offsetting mechanisms are there through which Brexit will enrich us? Despite having years to answer this question, Leavers have so far come up with nothing but smoke.

For me, then, acknowledging complexity is a reason to oppose Brexit. Not, necessarily, in the sense of *knowing* for sure that it���s bad. But rather in the sense of seeing no advantage in adding more uncertainty to an already-complex world.

I suspect that Cummings��� incorrect inferences don���t stop here. It is correct, wise and important to say that ���rapid error-correction��� is valuable. But how do we achieve this?

It is not by relying upon smart people and superforecasters. Being clever is like having a wank ��� self-gratifying but of little use to anyone else. Instead, I���d suggest three other things.

First, avoid the obvious errors in the first place. We now have a long inventory of cognitive biases. Much of my day job consists of warning retail investors to be on guard against these. Policy-makers should also be vigilant. But I see little evidence that they are: the most important such bias, says Daniel Kahneman, is over-confidence. How much of this is there in politics?

Secondly (and relatedly) avoid judgment and stick to rules. The investment environment, for example, is tremendously complex. The solution is to stick to a few rules, such as holding tracker funds; avoiding high-fee funds; and reducing exposure when prices fall below a ten-month average. The analogue on politics is to rely upon a few things that you know for sure.

Thirdly, we need automatic feedback which corrects errors: this is the great virtue of the market mechanism when it operates properly. Such feedback loops can be imported into policy-making. We know ��� thanks to the work of Prakash Loungani ��� that economists cannot forecast recessions: that���s consistent with complexity. Even the best monetary and fiscal policies, therefore, can only repair the damage after the event. What we need instead are powerful automatic stabilisers which include progressive taxes and a strong welfare state.

In the same way, labour market regulations and complicated welfare policies entail all sorts of trade-offs and uncertainties. One answer to such complexity is to pursue a simple alternative. As Dan Davies says: ���whatever your favourite social policy might be, full employment is probably the best way to achieve it.���

So, I suspect Cummings has drawn entirely wrong inferences from his premise. But I cannot be harsh on him, because in acknowledging complexity he has made a leap which most of the rest of the political-media class has not. And until they make that leap, the important question of how we cope with complexity will not get the attention it deserves.

Chris Dillow's Blog

- Chris Dillow's profile

- 2 followers