Chris Dillow's Blog, page 4

March 8, 2024

On lazy moralizing

Politicians prefer lazy moralizing to intellectual enquiry.

I say this because of Sunak's speech last week in which he condemned far-right extremists "who are hostile to our values and have no respect for our democratic traditions." What he did not do in that speech is ask: why has right-wing extremism increased from a nuisance to something more troubling?

His opponents were quick to point out that Sunak's Tory colleagues have been promoting it. But that's only part of the answer. Anderson and Braverman have been sowing their seeds in fertile ground. We now have abundant evidence corroborating Ben Friedman's 2006 finding that economic stagnation breeds illiberalism and hostility to democracy. Ana Sofia Pessoa and colleagues have shown that "fiscal consolidations lead to a significant increase in extreme parties' vote share." Markus Brueckner and Hans Peter Gruener have described how "lower growth rates are associated with a significant increase in right-wing extremism". And other researchers have shown how deaths of despair - which are symptoms of underlying social problems - are correlated with higher support for Brexit and Trump.

Sunak, however, like Starmer, omitted to mention all this evidence. Public opinion is not an exogenous datum. It is shaped by socio-economic conditions and political activity. Intelligent politics wouldn't merely condemn some beliefs, but inquire into their origins.

This, however, is by no means the only sign that Westminster is divorced from social science. [image error]

Another example is the demand from many Tories for tax cuts and a smaller state. What this misses is that achieving this cannot be merely a matter of ideology and will-power. A smaller state requires particular socio-economic conditions, one of which is an economy healthy enough to provide decent public services with a lower tax take*.

Yet another example was Liz Kendall telling youngsters that there'll be "no option of a life on benefits". This is mere punching down which not only begs the question of how many people actually want such an option, but also deflects attention from much bigger economic issues, such as how to end our 15 years of stagnant productivity and real wages.

What we have in all these cases is vacuous moralizing where there should be serious thinking about the social sciences. Gary Younge is dead right to say that the commentariat is "more interested in denouncing what is happening than understanding���why���it is happening." And Phil Burton-Cartledge is right to say that political commentary is "superficial" with no grasp of the social relations, the articulations of interests". And what's true of commentators is true too of politicians. As Lewis Goodall recently tweeted:

The Westminster (and much of the internal Conservative) conversations continues to miss everything which is driving [the collapse in Tory support] - the quietly radicalising effect of a collapsed NHS, a broken housing market, near bankrupt local government, a still sclerotic economy.

In one respect, this ignorance is unusual. Thatcher and Blair both entered office with some ideas about society and the economy - Thatcher about how we needed to curb trades union power and bring down inflation and income tax rates down and Blair about how social democracy could be updated to tackle late 20th century social problems. Starmer's Labour, by contrast, shows no similar sign of engaging with social or economic analysis. There is, in media-speak, no "narrative."

Why is this?

Partly, it's part of a general decline in intellectual standards, which has seen the expunging of intellectuals from public prominence. It's always easy to prefer lazy moralizing to serious thinking: such moralizing, of course, has as much connection to serious moral philosophy as economicky talk has to proper economics.

One reason for this decline lies in the dominance of the worst sort** of journalist, the Westminster political correspondent who views everything through the single lens of what plays well to their own tiny minds. Starmer can get away with drivel about the Tories maxxing out the nation's credit card because it is a good "attack line". The truth? Well who gives a damn about that?

The dominance of that sort of journalism has another effect. Politicians' priority is to respond to 24-hour news, and news itself has a bias in favour of salient individual events and against slower-moving trends. This means that important emergent trends - those underlying forces shaping public opinion - are neglected: the rise of immaterial labour which has contributed to liberal attitudes among the young; the economic stagnation that's led to illiberal reaction among others; or the rise of an unpropertied graduate cohort that feels alienated from politics.

Such ignorance is of course reinforced by the media's class bias: although most journalists are poorly paid the most dominant media figures are not, and come from a privileged elite (pdf) which feels little need to understand society and economics.

Such insularity and incuriosity means that the political class has been systematically surprised by important developments such as Brexit, the popularity among the young of Corbynism or the sudden collapse in support for the Tories.

But there's something else. Labour and the Tories are scared to look at the economy for fear of what they might find. It's unlikely that productivity and real wages can be raised much by mere tweaks acceptable to the forces of conservatism and their gimps in the media. Instead, thinking people who are not especially leftist now realize that promoting growth requires changes in property rights: higher taxes on landlords; less power to nimbys to block new building; the break-up of big companies; less restrictive intellectual property law; and tax simplification. All of these measures would be opposed by powerful interest groups. And that's before we even consider the possibility that inequality and even capitalism itself might be barriers to growth.

Attacking benefits claimants or migrants is easy. Attacks upon the powerful - land-owners, financiers, rentiers and monopolists - are not.

Taking the easy line, of course, runs into the dilemma: either we see public services decline even further, or taxes have to increase still more. Either risks further enflaming hostility to the political class - a hostility which will not take an intelligent or enlightened form.

You might think there's a way out of this dilemma: politicians should show some intellect and courage. But then, to call for this in the absence of socioeconomic conditions that produce such people is itself another form of lazy moralizing.

* There are other pre-conditions. Marxists would point to an absence of class struggle, whilst the right might point to a society and culture of individual or community self-help. All agree that a smaller state is the product of social conditions, not merely a moral desideratum.

** There's stiff competition, from financial journalists who can't distinguish between expertise and vested interest or from music journalists who don't know an ostinato from off stump.

March 1, 2024

You're a Marxist!

Many of you are Marxists - even though you might not realize it.

To see what I mean, consider the following:

One reason for Britain���s high costs in construction may be the result of NIMBY power. We need therefore to reduce this power, perhaps by allowing home-owners to vote (pdf) on schemes that would enable higher-density building. We also need to reform the tax system by replacing business rates with a commercial land value tax, which would be payable by the landowner, not the business. We need also to rethink intellectual property laws as the present patent system restricts growth and innovation. We must break up inefficient monopolies such as Openreach to foster more competition. And we must enforce the end-to-end and right-to-exit principles in order to weaken big tech and so foster new tech start-ups and the development of the internet.

There's a common theme behind these proposals. It's a belief that we need to restructure property rights - reducing those of patent-holders, landlords and monopolists and big tech - because existing ones constrain growth. Which is just what Marx thought happened:

At a certain stage of development, the material productive forces of society come into conflict with the existing relations of production or ��� this merely expresses the same thing in legal terms ��� with the property relations within the framework of which they have operated hitherto. From forms of development of the productive forces these relations turn into their fetters.

Those calling for these changes, however, don't think of themselves as Marxists: I've quoted Sam Dumitriu, Sam Bowman, Ben Southwood, Stian Westlake and Cory Doctorow*. But in claiming that property relations have become fetters on growth, they are thinking in terms consistent with Marx. [image error]

And not just on this point. They presume that their proposals are feasible. They believe therefore that when there is a mismatch between what economic growth requires and actually-existing property relations it is resolved by the latter changing rather than by us having to accept stagnation**. This is what G.A. Cohen, in his Karl Marx's Theory of History: A Defence, called the primacy thesis: "the nature of a set of production relations is explained by the level of development of the productive forces".

This is historical materialism. I therefore welcome our new Marxist colleagues.

In being Marxist in this sense without knowing it they have an illustrious predecessor - Mrs Thatcher. The defining feature of her government was the belief that production relations had become a fetter on growth, and that these had to (and could) change. Hence the cuts in income tax - increasing income-recipients' property rights - and reductions in trade union power, which shifted the balance of power within production relations in favour of capital.

Thatcher was a better Marxist (and more successful politician!) than most of her Labour critics. Except for a short-lived sign of intelligence under John McDonnell, the party has not had in recent years a well-worked theory of how property relations must change to facilitate growth. Marxists and Stian and colleagues know something that social democrats often miss - that fostering economic growth sometimes requires more than merely looser fiscal policy.

Of course, accepting one Marxian proposition does not make you a Marxist, any more than my accepting Burke or Hayek's points about bounded knowledge and rationality make me a Burkean or Hayekian***. You can accept Marx's historical materialism which rejecting some of his other ideas such as alienation and reification; ideology; the labour theory of value; tendency for the profit rate to fall (pdf); and the centrality of economic class. I suspect you'd be wrong to do so, however, but then I also suspect that many non-Marxists haven't so much considered these ideas and rejected them so much as they just haven't thought about them at all.

Equally, of course, we Marxists aren't so confident that the incompatibility between the development of the forces of production and current property relations can be solved merely by moderate tweaks to the latter. It's possible that low profit rates (and expected profits) are stifling innovation and investment; that the crisis-prone nature of capitalism is also doing so (we're still living with the legacy of 2008); and that capitalist hierarchies are also inefficient. If so, more radical changes are needed than Dumitriu, Bowman, Southwood and Westlake are calling for. My view on this is merely empirical: we should go down their road and then see if we need to go further.

The fact that so many people are historical materialists in a loose sense does not of course make the theory true. Many of us would resile from its teleological element - the idea that it must inevitably lead to socialism. Others have questioned Marx's idea that production relations will change to enable the forces of production to develop on the grounds that it invokes functional explanations which can sometimes be suspiciously like just-so stories****: Wright, Levine and Sober's Reconstructing Marxism is good on this debate. And yet others might question whether we need big organizing theories at all: what's wrong, they say, with small-scale granular ideas of history or economics?

These are open questions. My point here, though, is to emphasize something that's often forgotten. Marxism is not just a normative theory of what should happen and it's certainly not, as Tories want to claim, some sinister conspiracy of loons. Instead, it is part of the western intellectual tradition - a set of ideas (many derived from Marx's predecessor's) which can help organize our ideas today. Non-Marxists shouldn't be so squeamish about borrowing his ideas or acknowledging his influence upon them.

OK then: some people distinguish between Marxians (those influenced by Marx's ideas without subscribing to revolutionary socialism) and Marxists. If you like this distinction, the Sams and Stian are Marxian. But, hey, why spoil a good title?

* I suspect, however, that Cory Doctorow, who advocates breaking up big tech firms, wouldn't be so surprised or alarmed to be called Marxist.

** Yes, dear reader, I am eliding here the distinction between what should happen and what does happen. But then, I'm not sure Marx wasn't doing the same.

*** Perhaps the difference between me and some others is that I acknowledge the fact that I think within intellectual traditions and make no claim to originality.

**** It's possible that the process is a little like natural selection in biology. "Goodish" production relations do eventually get selected for because people with an interest in developing the productive forces sooner or later get the power to change them. Such a process is consistent with there being long periods of tension between the productive relations and productive forces, just as somewhat maladapted species can survive for a while.

August 31, 2023

Thatcherism is dead: Thatcherism lives

Thatcherism is dead. It has ceased to be. It has expired and gone to meet its maker. It has kicked the bucket, shuffled off this mortal coil and joined the bleedin' choir invisible. That seems to be the obvious inference to draw from Penny Mordaunt's call for the reintroduction of national service.

Let's call this what it is - forced labour. Whereas Thatcher long and loudly proclaimed the value of freedom - so much so that the Economist's obituary labelled her a "freedom fighter"- her epigones now want to deny people the most basic of freedoms of what to do with their lives, thus rejecting Thatcher's assertion that "a man's right to work as he will" is "the essence of a free economy."

This, however, is by no means the only way in which today's Tories are profoundly anti-Thatcher.

She declared the single market to be ���a fantastic prospect for our industry and commerce��� which offered ���complete freedom for our manufacturers, our road hauliers, our banks, our insurance firms, our professions to compete.��� The Tories have of course ripped up these freedoms.

Thatcher also thought that a key role for government was to provide stability, so that companies could plan better for their futures:

An economy will work best when it is built on a framework of clear and predictable rules on which individuals and companies can depend when making their own plans. Government's primary economic task is to frame and enforce such rules.

Today's Tories, by contrast, lurched from creating years of uncertainty about Brexit to inflicting the ideological fanaticism of Truss upon the economy. "Fuck business" was perhaps the only sincere thing Boris Johnson ever said.

Also, the Thatcher government favoured a tax system that was neutral between income and capital gains, so that labour was not penalized relative to capital ownership: Nigel Lawson argued that taxing the two differently "creates a major tax avoidance industry". Today's Tories, however, regard tax-dodging as a feature not a bug, and want to encourage rentierism at the expense of real work.

And then, of course, there's home ownership. Thatcher was smart enough to know that if you wanted people to support capitalism you had to give them at least a chance of owning property. Today's Tories have forgotten this. Which explains one massive difference between the 80s and now - that in the 1987 election the Tories actually led Labour by 39-33% among 25-34 year olds, whereas today (pdf) less than 15% of under-50s support them.

It's not just the Tories who have abandoned Thatcher, though. So too in many regards has public opinion. The majority of voters support public ownership of utilities and transport companies and a wealth tax. And many opponents of London's ULEZ plan favour vandalising cameras, which would have horrified Thatcher with her strong support for the rule of law.

Thatcher, it has been said (by John Gray, I believe), hoped to create a society of men like her father - a hard-working entrepreneur in a market society - but in fact left us one with men like her son, a talentless amoral grifter who made money by exploiting political contracts. We see evidence for this is not just in the economy's regress to feudalism in which wealth depends upon political power and asset ownership, but also in daytime TV. Programmes such as Homes Under the Hammer and Bargain Hunt show that the British public prefer to make money from rising house prices and selling tat rather than from the hard work, innovation and entrepreneurship which Thatcher lauded.

But, but, but. Despite all this. many Tories still think of themselves as Thatcherite, and many leftists believe our economy is Thatcherite. How can we explain this?

Simple. Although Thatcherism was an abject failure in terms of promoting support for widespread freedom and creating an entrepreneurial property-owning market economy, it was a success in another respect. It certainly did increase inequality. What matters here is not just income inequality, although the share going to the top 1% has risen from 6.8% to 12.7% since 1980. Inequalities of power in the workplace have increased with the smashing of trades unions and reassertion of "management's right to manage" (a now-overlooked Thatcherite slogan). And so too have inequalities of political power: whereas Labour used to be "in hock to the unions", it now defers abjectly to the billionaire-owned media.

And it is these inequalities that the right values far more than rhetoric about liberty and free markets. As Corey Robin has said, "the priority of conservative political argument has been the maintenance of private regimes of power." Or as the man put it:

The Tories in England long imagined that they were enthusiastic about monarchy, the church, and the beauties of the old English Constitution, until the day of danger wrung from them the confession that they are enthusiastic only about ground rent.

August 13, 2023

Benefits for capitalists

A recent Yougov poll found that most people think that people out of work should not be able to afford smartphones, takeaways, visits to the pub or pets. This is not just evidence of their mean-spiritedness, but also of their anti-capitalist attitudes.

I say so because of a basic economic idea - the circular flow of income. Out-of-work benefits are not so much payments to people as payments through them. They are payments to Greggs, Primark and Aldi and other places where recipients spend their money. Just as there's tax incidence, so too is there benefit incidence. The beneficiaries of benefits are those capitalists and employees who sell to the unemployed.

In this way, benefits serve several useful functions.

One is that they help to stabilize demand and cushion us from recessions. Monetary and fiscal policy cannot do this simply because, as Prakash Loungani has shown, recessions are unpredictable. The best such policies can do is hasten the recovery. To moderate the downturn we need automatic stabilizers of which out-of-work benefits are one. This matters, because stability tends to boost investment, as Nick Bloom has shown.

Secondly, such benefits subsidize and hence facilitate the creative destruction which is necessary for higher productivity. When benefits are mean we see more violent opposition to redundancy plans; less geographical mobility because people want to stay close to family and friends who could support them in hard times; and people being loath to move into potentially good but insecure jobs. In all these ways, out-of-work benefits help increase labour mobility.

To see a third benefit, imagine out-of-work benefits were increased. Recipients would probably not spend much of the extra on gas and electricity, but would do so on little treats - better food, a night out and suchlike. More spending on "luxuries" would therefore help increase the size of the competitive sector of the economy relative to the monopoly sector. It would support entrepreneurs against rentiers. That's good not only for allocational efficiency but also for dynamism and growth.

And for something else - the legitimacy of capitalism itself. An economy dominated by rentiers and monopolists is one that will struggle to justify its existence. One that can plausibly claim to give people what they want at reasonable prices has less difficulty.

In all these ways, intelligent capitalists favour reasonable out-of-work benefits. It's no accident that, in many countries, they were introduced not by leftist governments but by pro-capitalist ones.

Of course, against all these advantages must be weighed two potential drawbacks.

One is that when we are near full employment such benefits must be paid for by taxes or cuts in other parts of government spending, and those taxes would curb demand for the outputs of the competitive sector.

I'm not sure this is a grave problem though. If instead benefits were paid from a clampdown on procurement and subcontracting costs, the competitive sector would benefit relative to the extractive rentier sector. You might not like Tim Martin's politics, but a healthy economy has more Wetherspoons and less Capita.

A second possible drawback is that higher out-of-work benefits could reduce work incentives. This, however, is not a knock-down argument. For one thing, we could get people into work by making them fit to do so, for example by reducing NHS waiting lists. For another, work incentives are about the gap between out-of-work and in-work incomes. If both of these rise so that the latter remain well above the former, work incentives remain strong. And for another, a tight labour market should be a good thing as they encourage firms to economize on the use of labour by investing or improving working practices.

My point here is that you don't need to be a bleeding heart lefty to favour decent benefits for the unemployed. In fact, they are in the interests of capitalists (and people in work) themselves.

Which poses the question: why then, as that Yougov survey showed, is there such hostility to them?

One answer is overconfidence; people in work don't expect to lose their jobs, and so regard out-of-work benefits as payments to others rather than as insurance for themselves.

Another answer, I suspect, lies in reference group theory. We compare ourselves (pdf) to those around us, so many people on low incomes resent benefit claimants more than rich bosses - a resentment reinforced by our tendency to hate being thought of as mugs.

Whilst these might help explain popular antipathy to benefits it doesn't explain the Tories' hostility. Instead, this lies in a nasty fact, that there's something the right loves more than capitalism, and certainly more than free markets - hierarchy and inequality. As Corey Robin wrote:

The conservative defends particular orders ��� hierarchical, often private regimes of rule ��� on the assumption, in part, that hierarchy is order. (The Reactionary Mind, p24)

Decent welfare benefits undermine hierarchy. And for many on the right, defending inequality is more important than promoting well-functioning market capitalism.

August 4, 2023

The labour shortage "problem"

One of the tricks of bourgeois politics is to blame workers for the systemic failures of capitalism. So it is with the claim that there's a problem with increasing numbers of over-50s being out of the workforce. The Guardian, for example, says:

This is placing strain on the labour market, with many employers struggling to recruit, and is part of the reason for high inflation, the Bank of England has said.

The numbers, however, don't bear this out. There are now 3.47 million people aged between 50 and 64 who are economically inactive. Whilst this is 250,000 more than at the 2019 low-point, it is less than a year ago and less than the average in the 20 years before 2008.

Which poses the question: if 3.5 million over-50s being economically inactive was not a problem before 2008, why do the Bank of England and government think it is now?

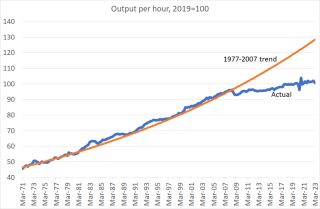

A big reason is that we've had 15 years of flatlining productivity. We need to work harder - and have more of us doing so - because we are not working smarter.

Had GDP per worker-hour grown at the same rate since 2007 as it did in the preceding 30 years, it would now be 28% higher than it actually is. That means the average worker could be over ��150 a week better off, or that all of them could take a day off a week without being worse off than they are now.

As it is, though, we are a poor country. To produce the things we want - that is, to overcome the lack of capacity which the Bank believes to cause inflation - we therefore need more workers simply to make up for our inefficiency.

One reason for this inefficiency is that many people are in the wrong jobs. There are the bullshit jobs described by David Graeber; guard labour such as supervisors, security guards and some middle managers which are needed to overcome the distrust engendered by capitalism and inequality; too many lawyers and accountants because of the complexity of the tax system; too many Border Force or DWP employees because of malevolent policy choices; and a bloated financial sector because of unpriced risk pollution and an false and ideologized perception of the fund management industry.

If bosses are "struggling to recruit" it is because too much labour is absorbed in doing things that are the product of capitalist failure.

But there's something else. Very few people have the luxury of cushy, enjoyable jobs where their employer will indulge their writing bullshit and harassing co-workers. Instead, many 50-somethings are leaving employment because it is dull or stressful - things which are often the result of rank bad management (and the public sector might be even worse than the private in this regard).

It was Adam Smith who wrote:

The man whose whole life is spent in performing a few simple operations, of which the effects are perhaps always the same, or very nearly the same, has no occasion to exert his understanding or to exercise his invention in finding out expedients for removing difficulties which never occur. He naturally loses, therefore, the habit of such exertion, and generally becomes as stupid and ignorant as it is possible for a human creature to become. The torpor of his mind renders him not only incapable of relishing or bearing a part in any rational conversation, but of conceiving any generous, noble, or tender sentiment.

Why wouldn't anybody who can afford to do so want to escape this fate?

This is especially the case because capitalism is the thief of time. As Marx pointed out, we must work longer than we need for our own ends because we must also work for capitalists and the state*. As we get older we appreciate that our time is running out - a point brilliantly made by Martin Hagglund's This Life - so this surplus labour time becomes more onerous.

My point here is simple. Insofar as government and capital need more people in work, it is only because of the failure of capitalism; the failure to increase productivity recently; the failure to allocate labour efficiently; and the failure to offer satisfying work. The labour problem is therefore in reality a capitalism problem. The system's lackeys and useful idiots, however, must go to great pains to deny this truth.

* We might add that many of us must also work for landlords, but this will actually keep younger people in work for decades.

Another thing. Some Tory fool says we over-50s can become Deliveroo drivers. Having been knocked off my bike yesterday by somebody who didn't realize that we drive on the left in this country, I have a lively impression of why people might choose not to do this.

July 24, 2023

The right's "woke" capitalism problem

Whatever happened to the right's faith in market forces? I ask because of their complaints about "woke capitalism" after Coutts refused Nigel Farage's custom.

Farage says:

I find it extraordinary that in modern corporate Britain, being seen to be politically correct matters more than making profits.

In theory, though, market forces should solve this problem. Imagine a business were to systematically turn away customers whose views it didn't like. Then a rival company that wasn't so fussy could serve them. This rival would expand at the expense of the "woke" one, possibly even driving the latter out of business. In a well-functioning market economy, companies have to care about making profits because if they do not they go bust.

There's an analogy here. Gary Becker claimed that this would be the fate of racist employers. Companies that discriminated against black people - that is, ones that thought that being politically incorrect mattered more than making profits - would, he said, suffer a competitive disadvantage as non-racist rivals hired good black workers or served black customers.

This isn't wholly fanciful. Becker pointed out that young industries with small growing companies were less likely to discriminate than older bigger firms where market forces weren't so powerful; in the 1920s Hollywood and Tin Pan Alley were more hospitable to Jews or blacks than less competitive banks or steel firms.

And in the 1970s black footballers were rare, partly because of racist stereotypes of them being lazy and ill-disciplined. Then West Brom manager Ron Atkinson* signed the "three degrees" and his team, inspired by them, did so well that other teams hired black players. Yes, those stereotypes persist but there are countless more black players in football now than there were when I was a kid.

The analogy is not perfect, however. Whereas racist businesses refused to hire or serve black people, "woke" ones are generally not refusing to employ Remainers or declining their custom: Coutts is closing Farage's account because it will no longer meet the criteria it imposes on all accounts, as Frances Coppola has explained.

But the point holds. If people don't like "woke" companies, there's a market opportunity. Non-"woke" companies can appeal to them and take business from the "wokesters". Competition should select against companies that pursue goals other than maximizing profits. Companies who think that "being seen to be politically correct matters more than making profits" should therefire shrink and go out of business. The market should solve the problem of "woke" capitalism, just as Becker thought it should solve the problem of racist capitalism.

Granted, it does so at a cost. Becker warned that the profit-maximizing solution would lead to racial segregation as black workers flocked to non-racist companies or served black clients rather than racist whites. But I don't see this applying to "woke" and "non-woke" firms. Yes, there are probably more Remainers in Starbucks or Prets than in Wetherspoons, but this probably reflects our big demographic divide than the professed ideology of those businesses. We're a long way from Jim Crow.

Also, it's not clear historically how far Beckerian competition caused racist companies to decline rather than the effects of legislative and cultural change. Which poses the question: could it be that the right whine about "woke capitalism" because it fears it is on the wrong side of cultural change and so cannot hope to reverse the tide of "wokeness"?

But the question remains: why hasn't the market (yet) selected against "woke" businesses?

One thing Farage has said actually sharpens the question: "they're all woke; they're all remainer". But this just means there is a bigger potential market for a non-"woke" company.

There's one answer Becker gave to this question that doesn't seem to apply. Profit-maximising employers, he said, had to consider the tastes of their customers or of other workers. They could lose business if racist customers refused to eat in the same cafes as black people, and lose staff or productivity if racist workers were unhappy to have black colleagues. And so even profit-maximizing firms might discriminate against blacks.

But this doesn't apply to "woke" companies today. Coutts is not closing Farage's account because "woke" customers refuse to bank with a firm that has him as a client. Nor are other "woke" capitalists such as Starbucks or Ben & Jerry's facing an efflux of customers who refuse to buy coffee or ice cream from companies that might occasionally sell to Brexiters.

Instead, I suspect the answer lies in a mundane fact - one that applied also to racist or sexist companies. Quite simply, the wheels of competition do not grind finely. Nick Bloom and John Van Reenen have shown (pdf) that there is "a long tail of extremely badly managed firms." If market forces don't weed out these, why should they weed out "wokesters" - especially as professing (not necessarily sincerely) political correctness might be a handy marketing strategy? There is, as Adam Smith said, a great deal of ruin in a nation.

It's easy to see why. In many industries there are big barriers to entry in the form of high capital requirements (have you tried setting up a bank?), intellectual property protection, the difficult of finding good premises, or simply the hassle to customers of switching.

Of course, lefties have pointed out such frictions for decades: that's why they were sceptical of the more optimistic interpretations of Becker's analysis.

What's odd is that the right has, implicitly, come round to agreeing. Which poses some questions. As Robert Shrimsley has asked, if the right no longer supports free markets what exactly is their mental model of the economy? And were the right ever sincere in the support for free markets, or was this support only strong when those markets were operating to weaken the working class?

* Atkinson, like many men of his time, had racist attitudes. Which shows that you don't need to be a saint to combat racism, but just someone who cares about winning football games and making money.

July 19, 2023

Fiscal conservatism, economic radicalism

Sir Keir Starmer has ruled out significant rises in public spending under a Labour government. He's partly right. What his supporters and many critics fail to appreciate, however, is that a tight fiscal stance is wholly consistent with some very left-wing policies.

First, why is he partly right?

The answer has nothing to do with "iron-clad fiscal rules". Such talk is merely to appease the nonces, imbeciles and billionaires' gimps in the media.

Instead, Labour's problem is that we are close to effective full employment; certainly, there are very few doctors or builders out of work. This means that any increase in public spending in excess of taxes would be potentially inflationary and would therefore (given the current inflation target) lead to the higher mortgage rates Sir Keir warns us of.

Just as Blairites fail to see that it's not 1997 any more, so some of Starmer's critics fail to see that it's not 2010 any more. There aren't the unemployed real resources to permit a significant fiscal expansion.

This does not, however, justify sticking with every detail of the Tories' spending plans such as the two child benefit cap. From an economic point of view, increased public spending is perfectly acceptable if it is matched by taxes which would offset the boost to aggregate demand. Sticking with the Tories' plans might be a coherent media strategy, but it is not an economic necessity.

Rigid fiscal discipline, however, by no means rules out radical policies. Here are a few Labour could follow:

Economic democracy.

It's no accident that our 15-year long stagnation in productivity and real wages followed rising inequality, because there are many channels through which inequality can depress output. Fixing this requires institutional change. As Joe Guinan and Martin O���Neill say:

The institutional arrangements at the heart of today���s British capitalism ��� concentrated private ownership, corporate dominance, and the overweening might of London-based finance capital ��� together form a powerful engine for the extraction of value and its distribution upwards. It is this basic institutional design that drives the outcomes we are seeing in terms of crumbling public infrastructure, social atomisation, environmental degradation, and a widespread sense of popular disempowerment.

Part of the solution here involves tougher regulation and tax reform, such as abolishing the carried interest anomaly - a fiscal tightening Labour should approve.

Another part requires the encouragement of more worker democracy (pdf), simply because we have evidence that this would raise productivity. As Virginie P��rotin puts it:

Worker cooperatives are more productive than conventional businesses, with staff working ���better and smarter��� and production organised more efficiently.

This could be done by - for example - using central and local government procurement to favour worker-owned companies or social enterprises; giving workers first refusal when a business is sold; encouraging lenders to better support coops (assuming that a National Investment Bank is off the agenda for wrong-headed fiscal reasons); or giving tax breaks to employee ownership schemes.

Tougher regulation.

Beefing up competition policy doesn't require more public spending. Nor does an attack upon regulatory capture: the revolving door between Ofwat and water companies' management shows that the former does a poor job of keeping the latter in its place.

We don't necessarily need nationalization to address this problem. We could convert water companies into franchises which bid for time-limited contracts to supply water, run sewage networks and so on.

Alternatively, the government could simply impose price caps itself on utilities rather than have captured regulators do so. The theory of the second-best shows us that where there is a market failure (such as a natural monopoly) another market "distortion" can be efficient.

Tax and benefit reform.

Taxes and benefits both need to be simplified. Reducing the conditions attached to Universal Credit, for example, would be a small step towards a basic income and would actually be "fiscally responsible" by cutting the number of administrators and work coaches.

And the goal of tax reform should be to shift towards taxing (pdf) inheritances and land rather than incomes - starting perhaps with a commercial land tax.

A maximum wage.

This is typically justified in terms of fairness, to stop executives earning hundreds of times more than their employees.

There is, however, a case for such a limit in terms of efficiency.

For one thing, big inequality can reduce an organization's efficiency as middle management spend their efforts on office politics or looking for the next job; or as they look to highly-paid bosses to give the lead rather than taking their own initiative.

Against this, you might argue that such a maximum would reduce the supply of talented bosses even more than it is currently restricted. This, however, could be a good thing: if it encourages the break-up of large firms it would decrease monopoly power.

If the maximum does not apply to companies where the CEO has a large ownership stake, it would have another advantage. It would encourage CEOs to set up their own companies. In this way, we'd get an increase in the number of talented entrepreneurs.

Now, I've not gone into detail on these because, to paraphrase Marx, there's no point writing recipes when you don't have a kitchen. Instead, I'm just saying that Labour could in principle be economically very radical even whilst having a tight fiscal policy and ruling out nationalization.

There's a strand of social democracy - I'm thinking of Polly Toynbee - which see politics largely through a tax-and-spend lens and which is therefore disappointed by fiscal restraint. Such a social democracy however works only if capitalism is healthy so that economic growth will deliver taxes. But capitalism is not healthy. We need radical supply-side measures to boost productivity.

You'll object here that the policies I've outlined are neither "practical" nor "credible".

And that's the point. Although these policies might well boost economic growth (and I've not mentioned rejoining the single market) whilst reducing inequality Labour is not offering them. Which suggests that its talk of fiscal discipline is not merely an economic policy. It is instead part of a wider message - of placating the right by showing that it is no threat to inequality and extractive capitalism. Labour is capital's second XI - and the second XI of the most backward and regressive parts of capital at that.

July 11, 2023

On being conservative

Katherine Birbalsingh recently tweeted something insightful:

"Having small c conservative values" is not political. Many lefties have them.

True. I think of myself as one of these.

The conservative disposition, wrote (pdf) Michael Oakeshott, "is averse from change, which appears always, in the first place, as deprivation." And there have been many changes in my lifetime which are indeed deprivations: the dumbing down of the public sphere and disappearance of the public intellectual; the loss of music teaching in state schools; the closure of thousands of pubs; the insertion into football of billionaire owners backed by repressive states; the loss of cleanish bathing water in our seas and rivers; the declining quality of popular music. And don't get me started on cricket.

But here's the thing. Many of these losses have been inflicted upon us by neoliberal capitalism: the privatization of water; the view that schooling (or at least state schooling) must merely prepare youngsters for labour; the opening up of English institutions to predators of all nations; and a university management which valorizes unreplicable "research outputs" over genuine intellectual work.

Not least of these impositions have been the forces that have diminished the traditional "middle-class". Financialization has led to thousands of people in professional jobs being unable to buy a house - a development which would have appalled Thatcher with her advocacy of property-owning democracy. And the professions themselves have been degraded by managerialism - hence gruelling hours and the loss of autonomy.

Neoliberal capitalism has done much more damage to the traditional English way of life than "cultural Marxism" or "wokesters" ever have.

In fact, the very use of those terms by the right is a sign of a temperament antithetical to small-c conservatism. Whereas small-c conservatism - as expressed by Burke or Oakeshott - advocates cool-headed scepticism and attention to empirical fact, talk of "wokesters" or "cultural Marxists" is that of fanatics who live in their own head or (what is just as bad) get their ideas of the world not from the evidence of their own eyes but from the scribblings of billionaires' gimps.

Not that their fanaticism stops there. Liz Truss was propelled into government by a small cult. And her belief that a tax-cutting Budget could boost growth even when the economy was close to full capacity was a denial not only of conventional macroeconomic thinking but also of Burke's conservative dictum:

Circumstances (which with some gentlemen pass for nothing) give in reality to every political principle its distinguishing colour, and discriminating effect. The circumstances are what render every civil and political scheme beneficial or noxious to mankind.

Her ill-fated premiership was at one with Brexit in this regard. The conservative, wrote Oakeshott, is "cool and critical in respect of change an innovation", preferring the tried to the untried. Brexiters, however, were the opposite of this - fanatics for change who, in most unBurkean fashion, over-estimated the capacity of government to achieve a satisfactory post-Brexit settlement.

"We tolerate monomaniacs, it is our habit to do so; but why should we be ruled by them?" asked Oakeshott, adding that goverment should "protect its subjects against the nuisance of those who spend their energy and their wealth in the service of some pet indignation."

In all these respects, therefore, the small-c conservative should be antipathetic to today's Tory party and to the neoliberal capitalism it (partially) represents.

Which leads to a puzzle. Ms Birbalsingh went on to commend National Conservatism as a grouping of small-c conservatives. Its defining features, however, seem to me to be not hostility to Brexit, Truss and neoliberalism but to migrants, "gender ideology" and "wokesters". Yes, there are complaints that policy-makers have put "the abstract goal of global free trade ahead of the economic welfare of all citizens." But the new right is defined more by culture war issues than by an antipathy to actually-existing capitalism.

Part of the reason for this is that conservatives love what they have come to know, which leads to Scruton's point*:

The disquiet over immigration [is] the result, it seems to me, not of racism, but of the disruption of an old experience of of home, and a loss of the enchantment which made home a place of safety and consolation. (England: An Elegy, p7-8)

This, however, runs into two problems. One is that migration isn't the only thing that's disrupting our old experience of home. So too (for example) is the environmental change caused by water companies and climate change. We would therefore expect anti-migration sentiments to be correlated with support for green policies. Whilst this is true in some cases, such as some nimbys or Zac Goldsmith, the opposite is more often the case: Ukip, for example, is campaigning against decarbonization policies and wants to reopen coal mines.

The second problem is that those areas that have actually experienced more immigration - and therefore one supposes more disruption of home - are more accepting of it; it was areas with low migration who were more likely to vote for Brexit, for example.

This might be because fear is worse than reality. Or it might be because of something else.

That something is that the idea of home is, for some, not merely an empirical matter of one's local area and the people and places we see every day but is instead a reified and ideologized notion. "Britain" is a bundle of symbols and myths, such as of a benign Empire or wholly heroic Churchill. And this "Britain" is identified with rich, white (and southern) people so that Russian agents are more "British" than Muslims or trades unionists. Which is a legacy of an old attitude described by C.B. Macpherson in The Political Theory of Possessive Individualism: "the poor were not full members of a moral community...They were in but not of civil society."

Such patriotism is thus a love of a cleansed and mythologized nation.

Which is paradoxical. For me, one of the attractions of small-c conservatism is its empiricism and distrust of abstractions and dreams. And yet small-c conservatives on the right too often invoke just such an abstraction - that of what Benedict Anderson called an imaginary community. This is not to say they are flat wrong: we all need myths and legends. It's just to say that we can and should separate small-c conservatism from anti-migrant sentiments. To fail to do so is to miss the many strengths of conservatism.

* Scruton went on to add that "the right of asylum is an untouchable provision of the English law", putting him to the left of today's Tories.

July 3, 2023

Inflation: a political problem

Why is inflation a problem? I ask because the common sense answer is wrong, whilst a standard answer among economists is out-of-date.

You might think the answer is obvious: inflation is making us poorer. Not so. Of course, wages haven't kept pace with prices, especially of food and fuel. But this, strictly speaking, isn't inflation. It is a change in relative prices. If utility bills were rising 17 percentage points faster than wages and food prices 12 percentage points we'd have a problem even if other components of the CPI were falling so that overall inflation were low.

Nor are higher mortgage rates a cost of inflation. They are a cost of bringing inflation down. And this is a policy decision in two senses: first to want to cut inflation; and secondly to do so through higher interest rates rather than through other means such as higher taxes or price controls.

We define inflation as a rise in the general price level, in which prices and wages rise at the same rates. What's so wrong with that?

For years, the standard view among economists was: not much, unless the inflation is unexpected. As Milton Friedman wrote (pdf):

Anticipated inflations or deflations produce no transfers from debtors to creditors which raise questions of equity; the interest rate on claims valued in nominal terms adjusts to allow for the anticipated rate of inflation. Anticipated inflations or deflations need involve no frictions in adjusting to changing prices. Every individual can take the anticipated change in the price level into account in setting prices for future trades. Finally, anticipated inflations or deflations involve no trade-offs between inflation and employment.

And in 1995 Robert Barro found that it was only high inflation - above 15% - that had a statistically significant impact in reducing economic growth.

Why, then, worry about inflation?

One answer is that it can raise taxes. If our wages rise by, say, 10% at a time when prices are rising 10% we are no better off. But that 10% rise will make us pay more tax, and push many of us into a higher tax bracket. Which is happening now. HMRC says that the number of people paying the higher rate of income tax rose by over 40% from 2020-21 to 2023-24.

I don't think this is a cost of inflation, though. It is a cost of the government's conscious decision not to index tax allowances to the rate of inflation - something which, thanks to the Rooker-Wise amendment of 1977, used to be the case.

Instead, Friedman's beef with anticipated inflation was different. Higher inflation and higher interest rates, he said, caused us to economize on holding cash; because it pays no interest it is more expensive the higher are interest rates. That in turn means that, rather than carry lots of cash on the hip, we have to make more trips to the bank which means we waste more time walking there and standing in queues. Economists called these "shoe-leather costs". In the late 90s, Bank of England economists estimated these to be significant - equivalent to ��60bn at the time, which is almost ��120bn in today's money.

But obviously, this is out-of-date. Many of us rarely use cash today; the quantity of notes and coins in circulation has fallen in the last two years, and many of these I suspect are sitting in vaults and jars rather than changing hands rapidly.

If shoe-leather costs are no longer so significant, then, what is wrong with inflation?

Maybe not much. Good judges have for years advocated raising (pdf) the inflation target, on the grounds that the benefits of low inflation are small and outweighed by a cost - of the risk of low inflation becoming a deflation which drags us towards the zero bound wherein monetary loses its efficacy.

I suspect, though, that there are reasons why inflation is a bad thing.

For one thing, it creates uncertainty; this is perhaps one reason why the inflations of the 70s and late 80s were accompanied by rises in the households' saving ratio.

The uncertainty here isn't just our reaction of "how much?!" when being charged ��13 for a pint of beer and glass of wine at the Hornblower. It's deeper than that. Inflation enriches some at the expense of others. And it does so not on the basis of contribution to society but upon factors such as: how real interest rates move; whether one has a nominal fixed income (such as an annuity or contract to deliver goods at a given price); or - of course - one's bargaining power. As Maynard Keynes wrote (pdf):

The sight of this arbitrary rearrangement of riches strikes not only at security, but at confidence in the existing distribution of wealth... and the process of wealth-getting degenerates into a gamble and a lottery. Lenin was certainly right. There is no subtler, no surer means of overturning the existing basis of society than to debauch the currency.

Right now, this "arbitrary rearrangement" is benefiting higher earners and larger capitalists who can exercise their greater bargaining power.

You might think this is welcome from a capitalist point of view.

Not necessarily. Capitalism requires not just favourable conditions for profit-making but also legitimacy. And inflation undermines this by reminding us that the notion that incomes depend upon marginal product is an ideologized fiction. Although discontent for now is manifesting itself only in lukewarm support for an unimaginative Labour party from mortgage-saddled former Tories, there's no assurance people will remain so passive if inflation persists. The inflation of the 70s, remember, fuelled sincere talk of a "crisis of democracy", and earlier hyperinflations in Europe had nastier effects.

From the point of view of rentiers and some larger capitalists (if nobody else!) British capitalism was working well in the low inflation era. Why risk rocking the boat?

June 14, 2023

The joyless polity

No, you can't. This is the mindset of our political class.

Labour has this week reneged on its promise to offer universal free childcare for children following Rachel Reeves' delaying of Labour's proposed ��28bn of green investments on the spurious grounds of the need to observe fiscal rules.

At the same time, the government - with Labour's connivance - is further restricting our right to protest. Which fits a pattern of hostility to freedom seen recently in the proposed ban on "buy one get one free" offers on fatty foods; the call for cycling helmets to be compulsory; and the demand from Darren Rodwell, Labour leader of Barking and Dagenham Council, to evict families if their children do not snitch on people who commit knife crime.

All this adds up to a pattern. The kneejerk attitute of our ruling class - both main parties and the media - is to say no. Not just "no, you can't do that", but "no, you can't have freedom of movement in the EU"; "no, you can't trade freely with our neighbours"; "no you can't have decent cycling infrastructure": "no you can't have an adequate train service in the north"; "no you can't have decent public support for culture": "no you can't have clean rivers"; "no you can't have free broadband." No, no, no.

Historically, there has been a debate about the merits of collective versus individual action. Our political class has resolved this by declaring neither to be feasible or desirable.

We also see this naysaying attitude in local transport. Too often, the emphasis is upon making car travel harder and more expensive rather than making public transport or cycling easier or cheaper.

We also see it in Starmer's "contract with the British people", which echoes New Labour's emphasis upon people's responsibilities and valorization of "hardworking families":

You can expect the opportunity to acquire new skills but you will be expected to work hard and do your bit. You can expect better neighbourhood policing but you will be expected to behave like good neighbours in your own community too.

To highlight my point, just ask: in what ways are politicians offering an expansion of our opportunities or freedoms? Thatcher allowed tax-payers to keep more of their money; people to buy their houses; and companies to trade freely with the EU. New Labour offered Sure Start centres and more support for the low-paid. But what's the offer now? Where are our ruling class saying (to anyone other than the ultra-rich): "yes, you can do that", or "yes, we can have that"?

George Orwell was exaggerating when he wrote: 'if you want a picture of the future, imagine a boot stamping on a human face ��� for ever." What we have is something much more familiar to him, that of a petty officious jobsworth saying no.

Why are we in this mess?

Some of the reasons lie in the fact that politicians, like all professionals, are selected to have particular casts of mind. One of these is that they are - in Jaap Stam's beautiful phrase - "busy cunts"; they are toilers running from meeting to meeting and expect the rest of us to lead such monomanic joyless existences.

Also, politicians are selected to have excessive faith in top-down management and to be overconfident about their ability to prescribe what the rest of us should do. The flipside of this is a scepticism - and often even lack of awareness - about the merits of spontaneous order as promoted by Hayek or Ostrom. And so politicians have an inherent bias against freedom - a bias which has the same roots as their lack of interest in economic democracy.

But there's something else, which I regret is not confined to politicians - something pointed out back in 1970 by the great Richard Sennett. Many of us, he wrote, create for ourselves "purified identities":

The threat of being overwhelmed by difficult social interactions is dealt with by fixing a self-image in advance, by making oneself a fixed object rather than an open person liable to be touched by a social situation. (The Uses of Disorder, p6)

This is what Margaret Hodge was (maybe unwittingly) getting at when she said that different food in the shops or different faces in schools "creates fear". If you are a fixed object with a fixed idea of what faces or food should be, then different ones are a threat to that identity and so a cause of fear. Hence the demand for immigration controls.

Hence too demands for crackdowns on other people who aren't like us, be they cyclists, protestors, or poor people wanting cheap food. The outgroup is a threat to be repressed, rather than part of a complex, diverse society.

There's one final thing. Contrast the joyless unambitious naysaying of our political class to John F. Kennedy's 1962 speech promising to put a man on the moon:

We choose to go to the moon in this decade and do the other things, not because they are easy, but because they are hard.

No British politician today could express such ambition: even Corbyn's modest social democratic proposals were decried as absurd.

Why the huge change? It's because capitalism has changed. In the 60s, the US's economic problem - described by Galbraith's The Affluent Society or Baran and Sweezy's Monopoly Capital - was that it's vast productive potential threatened to exceed demand. Kennedy's response to this was to invest skills and capital in the space race.

Today, however, there is no such potential. Two decades of stagnant productivity mean that nobody is optimistic about what we can achieve through either market forces or state direction. Keynes was of course bang right to say: "Anything we can actually do, we can afford." Our problem is that we cannot actually do very much. Talk of fiscal responsibility as a reason to row back on green investments might be pure drivel, but there is a better reason to do so - that we simply lack the skills and management ability to implement big investments quickly.

In this sense, naysaying is a response to capitalist failure.

Of course, another possible response would be ask why capitalism has failed and whether we can do better. But of course, to do this would be to commit a grave political sin.

Chris Dillow's Blog

- Chris Dillow's profile

- 2 followers