Chris Dillow's Blog, page 16

January 7, 2021

On bad government

There���s general agreement that the UK government has handled the pandemic badly in many (though not all) respects. Why?

It���s tempting to claim that ten years of Tory austerity has reduced the effectiveness of government and diminished NHS capacity: the UK has fewer doctors, hospital beds and ICU spaces than comparable countries.

Such a claim, however, runs into a problem. By some measures, the UK was actually reasonably well-prepared for the pandemic. In October 2019 the Global Heath Security Index ranked (pdf) the UK second in the world in its preparedness for the pandemic (just behind the US!). And the World Bank���s measure of government effectiveness placed the UK alongside the US and Taiwan - one of whom has handled the pandemic well and the other badly ��� and far above Vietnam, which has also controlled the virus.

This might tell us that such cross-country indices are flawed. Or it might tell us that the UK���s problem wasn���t with the state but with the government ��� a combination of Johnson���s own flaws and his having to kowtow to the lunatic fringe of the Tory party.

This too is plausible. But it too runs into a problem ��� that bad government long pre-dates Johnson. In 2013 Ivor Crewe and Anthony King published The Blunders of our Governments which analysed a litany of policy failures such as Individual Learning Accounts, public-private partnerships and various government IT projects: we might add the Iraq war to this. And even then, their complaint was not new. In 1995 Patrick Dunleavy wrote (pdf):

Britain now stands out amongst comparable European countries, and perhaps amongst liberal democracies as a whole, as a state unusually prone to make large-scale, avoidable policy mistakes.

Think of the monetarist experiment of 1979-81 which decimated industry, entering the ERM or the poll tax.

Not that policy errors began with Thatcher. Aris Roussinos likens the government���s errors in tackling Covid to the serial errors made in the early years of WWII.

From this perspective, Johnson is merely following a long tradition of incompetence.

But what causes this tradition? Paradoxically, Johnson���s errors have been the exact opposite of many of those identified by Dunleavy. He blamed ���overly speedy legislation��� and ���political hyperactivism���. But Johnson has been systematically guilty of the opposite ��� of acting too slowly.

There are, though, other structural faults.

Crewe and King cite a ���divorce between policy making and implementation���, arguing that Whitehall has traditionally valorized theoretical policy formulation over the dull grunt-work of management.

Crewe and King and Dunleavy also cite a lack of adequate checks and balances, perhaps exacerbated by our overly-centralized state ��� a problem magnified by George Osborne���s gutting of local government. It used to be said that one factor here, which distinguished us from mainland Europe, was our traditional lack of coalition government ��� although the 2010-15 experience has weakened this claim.

Another factor, they add, is a tendency to groupthink. This, I suspect, is worsened by the overconfidence of individual Prime Ministers. It might be no accident that our worst PMs disproportionately attended private school, as this inculcates (among other misperceptions) a tendency for one���s confidence to exceed one���s abilities.

There might be more ��� a fundamental problem with our political culture. It doesn���t even recognise what politics should be about. In principle, it should be about solving problems of collective action ��� of what happens when individuals pursuing their self-interest produce outcomes that are bad for us all. Too many people however ��� not least the media ��� don���t see this*. They think instead that a branch of marketing, or a game of jockeying for individual self-advancement. The upshot is that nobody takes proper politics seriously. Yes, Johnson is a clown ��� but he is a democratically elected clown, and thus a symptom of a problem.

For these reasons, conventional partisan politics misses an important fact ��� that it is not enough to get the right people elected; better government requires structural and cultural change.

But, but, but. If something persists for a long time, it���s because it suits some powerful interests. And a political system with the risk of big policy errors actually does this. Few people of influence care about competent government as long as taxes don���t rise or rents fall. And so dysfunctional government persists.

* Among those not seeing it is Whitehall itself. Our most powerful government department, the Treasury, has traditionally regarded the public finances as if they were a household���s finances. This is why governments have occasionally tried to circumvent the Treasury���s power by appointing ministers for economic affairs ��� without success.

January 4, 2021

What's given, what's not?

There is much talk of how Covid is putting pressure on the NHS. Such talk, however, often misses an important fact ��� that although NHS capacity is more or less fixed in the short-term, it is certainly not in the long-run. And past political choices have limited this capacity. For example, the UK has 2.8 doctors for every 1000 people compared to an average of three in OECD countries generally and more than four in Germany, Italy or Switzerland. We have only 2.46 hospital beds per 1000 people, compared to 8.0 in Germany or 5.9 in France. And we have fewer intensive care spaces than the average developed economy.

The NHS is under pressure because of past political decisions to limit its capacity. Failing to point this out exonerates what should not be exonerated ��� namely, a decade of fiscal austerity.

What���s happening here is, in fact, a widespread error ��� of regarding something as exogenous or given when it is in fact a creation of people, either deliberately via policy or inadvertently via emergent processes.

Another example of this mistake lies in the debate over how far Labour should accommodate itself to social conservatism. What some of this misses is that whilst there have always been social conservatives, they have not always been so salient or an insuperable obstacle to progress. Instead, the strength of social conservatism today is a product of economic conditions. As Ben Friedman has shown, stagnation breeds illiberalism. And Kenan Malik adds that, among working class voters, it is also ���the product of decades of neglect.���

The strength of social conservatism is partly endogenous. One trivial fact tells us this. It���s that before 2016 hardly any of us were ���leavers��� or ���remainers���; these are identities that were created by political debate.

There���s more to politics than merely giving punters what they say they want. As Kenan says, it is also ���about standing on a set of principles and trying to win people over��� ��� or, I would add, shifting the agenda from the culture wars to economics.

Social conservatism, though, isn���t the only example of public opinion being (partly) endogenous. Kris-Stella Trump has shown that the same is true of our attitudes to fairness. When inequality is high we regard that as fair, and when it is low we also see that as fair. Our perceptions of fairness are anchored by (what we perceive to be) the actual distribution of income.

Even the most intelligent social observers can sometimes fail to distinguish between the exogenous and endogenous. I���m thinking here of two otherwise excellent recent books, Case and Deaton���s Deaths of Despair and Thomas Phillipon���s The Great Reversal. Both show how capitalists have captured the state in order to extend their monopoly power. But their response to this is to advocate better policy, as if doing so were only a matter of intellect and goodwill.

Which it is not. Such proposals fail to see what they themselves have shown ��� that dysfunctional policy is endogenous, the product of capitalists��� political power. The remedy for this is not for policy-makers to simply try harder. It is for us to work for a stronger anti-(crony?) capitalist movement, so that policies to restrain rent-seeking become more feasible.

There is, of course, another example of confusing the exogenous and endogenous and one that���s been with us for decades. I���m thinking of the tendency to regard capitalism as natural, as the result of some innate human impulse to truck, barter and exchange. But this is not true. And believing that it is limits our ability to imagine a better world. As Ellen Meiksins Wood has written:

The naturalization of capitalism, which denies its specificity and the long and painful historical processes that brought it into being, limits our understanding of the past. At the same time, it restricts our hopes and expectations for the future, for if capitalism is the natural culmination of history then surmounting it is unimaginable. (The Origins of Capitalism, p8)

But capitalism is not natural. People have made it. And what we have made, we can change.

December 16, 2020

Alienation & doublethink

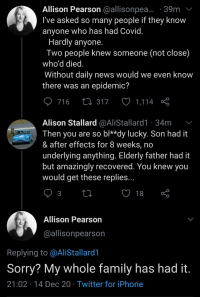

���The right side lost, but the wrong side won���. I was reminded of John Le Carre���s assessment of the Cold War by a recent exchange in which Allison Pearson claimed that she knew ���hardly anyone��� who knew somebody who���d had Covid only to immediately say that her whole family had had it.

This seems nonsensical. But it���s not. It reminds me of what happened in the former USSR, where the conflict between the reality of day-to-day life and the imperative to conform to ideology led to an Orwellian doublethink. As Timur Kuran has written:

The individual citizen���s mind was divided into two layers, one ���pragmatic��� and the other ���ideological���. The former layer contained the practical information necessary to get things done, derived mostly from experience���The latter consisted of abstract information, drawn primarily from public discourse. (Private Truths, Public Lies, p218)

People had to present different personalities. Kuran cites one Russian who said after the collapse of the USSR that he had six faces ��� one each for his wife; his children; close friends; acquaintances; colleagues; and for public display. There was, says Kuran, a sharp distinction between public and private opinion.

Ms Pearson was practising just such doublethink. Her public persona in the griftmedia required her to present an ideological face and downplay Covid, but her lived experience in her private life dictated otherwise. In that exchange she jumped from one face to another.

That she had to do so is the product of our latter-day media, well described by Sarah Ditum. She says she would look for ���something that I could be mad enough about to write 600-800 fiery words on it.��� But, she says, some of this writing ���had a dishonesty that made me feel ashamed���. As with Pearson and Soviet citizens, there was a public persona and a private one.

It���s not just journalism that produces such doublethink, however. Tony Yates tweeted yesterday:

I teach models with optimizing consumers, and spent 1/1000 time buying a new washing machines as I have so far spent sourcing a second hand 2nd bike.

Now, you can perhaps salvage some rationality from this particular example (see thread). But there is a general point there ��� that many academics have taught about optimizing consumers whilst knowing that such beasts don���t exist in reality. Students, Deirdre McCloskey has written:

Come to believe (until experience drives the madness out) that economics is about a certain mathematical object called an ���economy���. They have no incentive to learn about the world���s actual economy. (Knowledge and Persuasion in Economics, p173).

Again, we see a conflict between the public lie of academics telling their students about optimizing behaviour, and the private truth that they know people behave otherwise.

The point broadens. In Bullshit Jobs, the late David Graeber described the ���spiritual violence��� caused by a paradox ��� that our sense of self-worth is tied to working for a living, but we hate our jobs. Our jobs require us to pretend. Not just the pretence of grifter journalism or teaching about rational behaviour, but the pretence that managerialist waffle is meaningful or that bullshit jobs are actually worthwhile. Most of us, to some extent or other, must wrestle with the dissonance this causes.

This is of course not a new observation. Here���s Marx in 1844:

What, then, constitutes the alienation of labor?

First, the fact that labor is external to the worker, i.e., it does not belong to his intrinsic nature; that in his work, therefore, he does not affirm himself but denies himself, does not feel content but unhappy, does not develop freely his physical and mental energy but mortifies his body and ruins his mind. The worker therefore only feels himself outside his work, and in his work feels outside himself. He feels at home when he is not working, and when he is working he does not feel at home.

In capitalism, even well-paid, comfortable jobs ��� perhaps especially well-paid comfortable jobs ��� require a denial of ourselves and of reality, that we adopt a different personality.

Which brings us back to Le Carre. One good objection to Soviet communism was that enforced widespread dishonesty. People had to deny fundamental truths which thwarted their true natures and hence their freedom. That���s why the right side lost the cold war. But capitalism does the same thing. Which is why the wrong side won.

December 13, 2020

Restraining capital

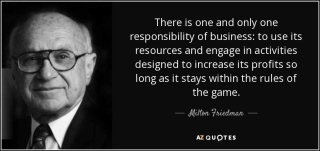

Martin Wolf argues that Milton Friedman was wrong to claim that the only social responsibility of business is to increase profits. I agree with him, but I fear he under-rates two important facts: historical context and class power.

Friedman thought (pdf) that profit maximization promoted the social good only under two conditions.

One, stressed by Luigi Zingales, is that markets must be competitive. Where this is the case, corporations have little power to egregiously exploit consumers or workers. In fact, they must maximize profits or go bust - and going bust is rarely in the public interest.

The second is that profit-seeking is only socially desirable so long as the firm ���stays within the rules of the game, which is to say, engages in open and free competition without deception or fraud.��� This echoes Adam Smith, especially as interpreted by Jesse Norman (pdf) ��� that a well-functioning market economy depends upon social norms.

However, things have changed since the 1970s so that even if Friedman was right then, he no longer is. There are four, inter-related developments here.

First, markets have become less competitive, as Thomas Philippon has shown.

Secondly, social norms have eroded. In the 1970s, pharmaceutical companies did not deliberately sell addictive opiates as they do today*. And whilst misreporting of earnings was rare in the 70s, it is more common (pdf) today, albeit less so than a few years ago.

Thirdly, firms are makers and not just takers of the ���rules of the game���. As Martin says, they successfully lobby for favourable rules. The US healthcare industry alone spends over ��500bn on lobbying, and employs five lobbyists for every one Congressman. Which is just profit maximizing behaviour. If it���s cheaper to campaign for handouts or lax regulation than to develop good products then profit maximization requires that firms do just this. The upshot is that as Martin Gilens and Benjamin I. Page say (pdf):

Economic elites and organized groups representing business interests have substantial independent impacts on U.S. government policy, while average citizens and mass-based interest groups have little or no independent influence

Fourthly, trades unions have greatly declined. In 1970 firms faced a countervailing power which inhibited them from cutting workers pay and conditions or jacking up CEO pay. Today, they no longer do so.

Now, these developments have been more pronounced in the US than in the UK or Europe. Their overall effect, though, Is to remove the conditions in which Friedman���s claim made sense. Which leads to Martin���s conclusion:

The challenge is to create good rules of the game, via politics. Today, we cannot.

That word ���cannot��� is important. Creating better rules of the game isn���t primarily about technocratic fixes such as rules again lobbying, breaking up the tech giants, raising banks��� capital requirements or (in the US) reforming healthcare. Any fool can have good ideas.

Instead, the issue here is power. The same forces that empower big corporations to make the rules also empower them to inhibit reform ��� or even to reduce the chances of a reforming government being elected at all; some of these forces are of course not under the deliberate control of specific capitalists but are rather emergent processes.

A lot of technocratic politics and economics is idle fantasising: ���here���s what I���d do if I were king���. It misses the point: how do we achieve the power to restrain big capital?

Centrists criticise the left for failing to see that good ideas are useless unless you win elections. But we can turn this jibe around. From the point of view of restraining capital, there���s a difference between winning office and winning power. As I���ve long complained, technocrats are too often blind to the realities of capitalist power.

The challenge for anybody wanting a healthy capitalism, then, is how to achieve the power, the leverage, to do so? Insofar as capitalism operated in the wider public interest at the time that Friedman was writing (which of course is a matter of dispute) it did so because it faced countervailing power. Today, it no longer does so to the same extent.

Here, the left has an insight, if not a successful application thereof ��� the need to build an anti-capitalist hegemony, something which can only be done outside of parliamentary politics.

There���s general agreement that non-parliamentary action can create such hegemony. Rightists who complain about ���wokeness��� allege that the left has just done this in cultural domains. Perhaps a better example, though is Brexit. Farage and Ukip were negligible as a parliamentary presence, but achieved their aims anyway.

Neither of these hegemonies, however, have greatly challenged capitalist power: although Brexit is not in the material interest of some segments of capital, it has the redeeming virtue of having deflected blame for stagnation from capitalism onto the EU and migrants.

Which leaves the question: is it possible to create an anti-capitalist hegemony, and if so how? Technocrats have been insufficiently interested in this question.

* Corporations did, however, produce thalidomide and DDT, though the adverse effects of these might have been partly unintended.

December 5, 2020

News versus emergence

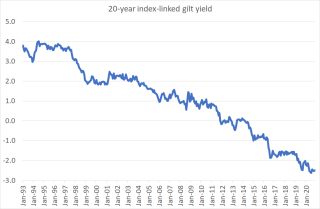

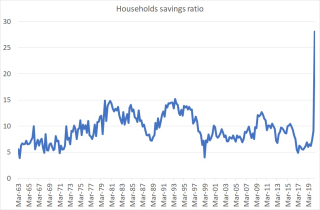

From an economist���s point of view, there are two big facts about the public finances. Fact one is that the government is now being paid to borrow. 20-year gilt yields are minus 2.5% which means that for every ��100 the government borrows it must repay only ��60 over the next 20 years. Fact two is that record government borrowing is, by definition, the counterpart of the fact that the household savings ratio hit a record high in Q2.

Many political journalists, however, underweight these facts. Laura Kuenssberg talks of the nation���s credit card being maxxed out, whilst Matthew Parris rages at those of us who have the temerity to criticise her.

Which poses the question: why is there just a gulf between political journalists and economists here?

I suggest it���s because political journalists and economists see the world differently. The news is usually about the day-to-day events of what individuals do and say. A lot of economics, however, is not like that. It is the study of emergence, of states of affairs which arise from decentralized human action but not intention. This isn���t just true of economics, but of the social sciences generally ��� which is why there are great limits upon what you can learn about history and politics from biographies alone.

Take, for example, the long-term decline in interest rates since the 1990s. This reflects a slowdown in economic growth in western economies ��� a fall into what Larry Summers has called secular stagnation. There are several possible (and non-exclusive) explanations for this. Maybe a falling rate of profit has reduced incentives for firms to invest and expand. Perhaps a shortage of safe assets and increased risk aversion has depressed demand. Perhaps there are fewer (pdf) big innovations to drive growth. Maybe the 2008 financial crisis has had a long-lasting scarring effect on animal spirits. Maybe firms have finally wised up to William Nordhaus���s finding that the returns to innovation are generally small. Or maybe the fear of competition from future technologies is deterring investment today.

For my purposes, all these explanations have some things in common. All are the result of countless decisions by countless individuals. They cannot be traced to the action of any single policy-maker. And they are gradual processes. At no stage in the last 20 years could we have said for sure: ���the world economy has today entered a new era of permanently slow growth.���

These processes get overlooked by journalists who are focused instead upon precise day-to-day events and the actions of identifiable persons. News is one thing; emergence another. And so journalists��� are insufficiently awake to the downtrend in interest rates.

Government borrowing is also an emergent process. It is at a record high this year because household savings are at a record high: the lockdown and fear of catching Covid-19 has kept us out of gyms, pubs and restaurants. None of us, however, thought: ���I shall save more and so cause the government to borrow more���. But that is the aggregate result of our actions. And the same economic weakness that arises from increased private savings also justifies the Bank of England���s buying of government bonds ��� which is another reason not to worry about government borrowing.

Both government borrowing, and the ease of financing it, are the result of emergent processes - processes which even good journalism under-rates.

Of course, political journalists can be forgiven for overlooking economic processes. Except that economic events shape political ones.

Anti-Europeanism, for example, has been a longstanding strand in UK politics: the Sun���s notorious headline ���Up Yours, Delors��� is now 30 years old. But in the late 90s and early 00s, the Tories were punished harshly in elections for their obsession with the EU. So what changed?

The economic climate, that���s what. Ben Friedman has shown that economic stagnation fosters intolerance and nationalism ��� perhaps because a sense of national decline leads to a yearning for the past. And Thiemo Fetzer and Nick Crafts have shown how austerity contributed to Brexit. It is wrong to treat public opinion merely as a datum; it is shaped by the economy ��� often in ways we can only identify with hindsight.

Emergent processes set the climate. But journalists who focus only on the day-to-day weather miss this. And so they worry unnecessarily about government borrowing ��� and mislead their viewers and readers, some of whom are politicians.

Now, I am emphatically not making a purely partisan point here. Emergence doesn���t only give us stagnation and Marxian exploitation. Hayek regarded the spontaneous order of a market economy as a benign form of emergence. And the decline in global poverty and disease in recent decades has also been (partly) an emergent process. Journalists��� bias against emergence also leads them to neglect these. And again, in doing so they mislead the public: people are unduly antipathetic to markets and under-estimate the extent to which living conditions have improved for billions.

The news, then, is not the whole truth. It is in this sense, rather than simple-minded partisanship, that the BBC is biased.

November 26, 2020

Maxxed out?

Laura Kuenssberg said yesterday:

���This is the credit card, the national mortgage, everything absolutely maxxed out. Enormous levels of the country basically being in the red.���

This is obviously the most abject drivel. (Hint: how many credit card companies will pay you to borrow when you are at your credit limit?) What interests me, though, is: how can any sentient being utter something so stupid?

Some of you will blame dishonesty and partisanship. But I suspect some more interesting, and insidious, errors are at work.

One is something I���ve complained about before. The BBC is insufficiently aware of emergence ��� the fact that many social phenomena are the product of human action but not deliberate design.

The public finances are one such phenomenon. It���s true that government borrowing has hit a record high this year. But so too has something else ��� the household savings ratio. Isn���t it a remarkable coincidence that two records have been broken at exactly the same time?

No, because they are the counterparts of each other. Every pound borrowed must equal a pound lent, so government borrowing is by definition the counterpart to private sector net saving. The lockdown, plus the health risks of going out and the uncertainty about our personal finances, has caused private sector net saving to soar. The counterpart to this is that government borrowing has also soared.

This is why I say government borrowing is emergent. It is an unintended result of countless private sector decisions. Which is why interest rates are so low: the same rise in private sector savings that causes government borrowing to rise also causes interest rates to fall.

If you have a bias against emergence ��� as the BBC has ��� you���ll not be alive to this. Instead, Ms Kuenssberg seems to regard government borrowing as the result of government agency, in the same way that an individual has control over her personal borrowing ��� hence her talk of credit cards. But this is not the case.

This error is compounded by others.

One is the failure to see that some opinions are more important than others. The opinion that matters about government borrowing isn���t Ms Kuenssberg���s or mine or yours. It is that of the people lending to the government, of gilt investors. And not only are these willing to lend at sharply negative real rates, but also they expect rates to remain negative for years. This fact alone tells us the ���credit card��� is not maxed out. Unless you are providing strong reasons why clever people with skin in the game are mistaken, your opinion is irrelevant waffle.

A further error is a lack of historic perspective. David Cameron claimed that ���our nation���s credit card��� was maxed out back in November 2008. Public sector net debt was then ��672.2bn. It���s now ��2076.8bn (much of which is owed to the Bank of England.) Mr Cameron was, therefore, plain wrong ��� by a factor of at least three. Anybody with a sense of perspective would ask: if he was so egregiously wrong then, why should the claim be right now? I fear that the obsession with 24-hour news cycles ��� and with over-dramatising stories - might have distracted Ms Kuenssberg from such a perspective.

Perhaps, though, there���s something else. It���s the valorization of talk over evidence. Ordinarily, somebody claiming that the nation���s credit card was maxed out would ask: what evidence do we have for this claim? In terms of objective fact there is of course none, zero, zip, diddly squat. In terms of talk, however, I suspect there is plenty in the circles in which Ms Kuenssberg moves, as many MPs (perhaps not all of them Tories) and political journalists have imbibed and recycled Cameron���s untruth. If so, Ms Kuenssberg has fallen into the common error of groupthink: as Robert Frank has shown, our views are often influenced by our peers. Ms Kuenssberg���s error is an egregious one, but perhaps not an isolated one.

Whether it is or no, the fact is that it is a costly error. An ONS report this week has found that the public is ill-informed about basic economics ��� a finding which corroborates other evidence of their lack of knowledge of social facts. As our dominant broadcaster, the BBC must be partly responsible for this ignorance. And I suspect the responsibility is not so much Ms Kuenssberg���s alone as it is the result of biases which are shared by many political journalists.

November 18, 2020

Full employment, capitalism & regress

The Guardian is reinventing the wheel. Its leader yesterday said:

Nobody but the government can take responsibility for maintaining the total level of spending in the economy at a level that keeps the country as close to full employment as possible.

Like all the best ideas, this is not original. In fact, it���s as new as powdered eggs or Woolton pie. It echoes this from William Beveridge in 1944 (pdf):

It must be a function of the State in future to ensure adequate total outlay and by consequence to protect its citizens against mass unemployment. (Full Employment in a Free Society, p29)

Which poses the question: why has Beveridge���s thought been so forgotten that it must now be rediscovered?

The answer is that, by the mid-70s, full employment was causing inflation, industrial unrest and a squeeze on profit margins, much of which vindicated Kalecki���s famous prophecy (pdf):

Under a regime of permanent full employment, the 'sack' would cease to play its role as a disciplinary measure. The social position of the boss would be undermined, and the self-assurance and class-consciousness of the working class would grow. Strikes for wage increases and improvements in conditions of work would create political tension.

Partly fueled by this, there was an intellectual backlash against Beveridge���s Keynesianism. Insofar as full employment was a policy aim at all, many economists thought it should be pursued by the control of inflation, supply-side reforms of labour markets such as controlling trades unions and curbing welfare benefits, and giving businesses a stable environment in which to invest and grow. Although this general approach took many specific forms - monetary targets were swiftly abandoned for example ��� New Labour largely continued it, as did the Tories with George Osborne���s idea of ���fiscal conservatism and monetary activism���.

This approach, however, has failed. Even at its low-point last year, there were 1.3 million officially unemployed, another 1.9 million out of the workforce wanting a job, and millions more not working the hours they���d like.

Which lends credence to the Guardian���s rediscovery of Beveridge���s claim.

But would this actually work?

In a sense, it���s not really ever been tried. We didn���t see much counter-cyclical fiscal policy in the post-war decades. Full employment probably owed more to the fact that the war had created a huge backlog of demand ��� although it���s also possible that the mere assurance that governments were committed to full employment helped sustain expectations of demand.

And it might not work this time.

If wage-led growth is to be feasible (pdf) capitalists must continue to invest in the face of incipient wage pressures in the expectation that aggregate demand would stay high.

But this is doubtful. Higher wages might not lead to proportionately higher demand. This would be the case if workers use their pay rises to pay off debt or save more, or if they buy foreign goods and services instead: some researchers have found that wage-led growth is less likely in open economies for this reason.

Also, there are two big differences between now and the immediate post-war period. Back then, capital spending and private sector hiring stayed strong because there was a backlog of innovations and a high profit rate. But as Robert Gordon and Michael Roberts have shown, these factors are now absent.

And then there���s the problem that neoliberalism is partly performative. For decades, industrialists have become accustomed to slack labour markets and a quiescent labour force. Ending this regime could in itself weaken animal spirits.

What���s more, a big section of capital would be ill-served by wage-led growth. Finance capital does well from weak aggregate demand because this cuts the interest rates on which leveraged strategies depend: Ford might have needed full employment; Goldman Sachs does not.

For these reasons, there���ll be strong capitalist opposition to a return to Beveridgeism - objections which I fear will apply just as strongly to a job guarantee. Which matters, because full employment is not merely a matter of technical know-how, but of class power. As Kalecki said:

The assumption that a government will maintain full employment in a capitalist economy if it only knows how to do it is fallacious.

But what inference should we draw from this?

It is NOT that full employment is impossible. Rather, it is that it is incompatible with capitalism.

This, of course, is not a new inference nor even a uniquely Marxist one. The monetarist/new classical backlash against Keynesianism was not the only intellectual response to the crisis of the 70s. There was another one. Some economists showed that full employment could be sustained with worker ownership: Martin Weitzman called this the share economy and James Meade wrote of labour-capital partnerships. Full employment created inflation because it fueled a ���battle of the mark-ups���. But if workers and capitalists are the same people, the battle lines disappear.

Beveridge actually anticipated something like this response. In 1944 he wrote:

Whether private ownership of means of production to be operated by others is a good economic device or not, it must be judged as a device. It is not an essential citizen liberty in Britain... If���it should be shown by experience or by argument that abolition of private property in the means of production was necessary for full employment, this abolition would have to be undertaken. (Full Employment in a Free Society, p23)

This approach has, however, been almost totally forgotten ��� including, it would appear, at the Guardian.

So great and so total has been the intellectual regress of recent decades that our most left-wing newspaper today is far to the right of a man whose mindset was that of a nineteenth-century liberal.

November 13, 2020

Our priorities

One of the dafter genres of political writing is the offering of unsolicited advice to leaders. Nevertheless, I���d like to suggest what I would do if I were Sir Keir Starmer. You can think of this as advice if you���d like, but I���d rather regard it as a way of contrasting two different types of politics.

What I���d do is to greatly beef up the party���s National Policy Forum, giving it more resources, a much higher profile and emphasising that it is open to all. We need ongoing informal and widespread public inquiries in which experts, the public and interest groups are engaged. These should be exercises in deliberative democracy in which devices such as citizens��� juries are combined with academic research.

Connecting with grassroots is not an alternative to technocracy. The two are complements because good policy requires a detailed knowledge of ground truth.

I stress here that these are not focus groups: the party must ask not ���what do you think?��� but ���what do you know?��� And the results of this research must form policy, and not be over-ridden by the instincts of party leadership or by the search for quick headlines. Phil says that:

Labourist politics relies on mass passivity, it's an elite project where the masses vote in the politicians, and they make the changes by passing legislation.

This must change.

Here are some examples of what I mean:

- What is global best practice? Why have some countries such as South Korea and New Zealand handled Covid much better? Why is French childcare so good and cheap? Why has Finland (until recently) had better education outcomes? Can we learn from these, or are there cultural factors that prevent us importing their success? And so on with respect to public transport, infrastructure, vocational training etc. In contrast to Tory waffle about a ���world beating��� test and trace scheme, Labour should have detailed empirical evidence on best practice in public services from around the world.

- How do we put in place the right policy infrastructure for fighting recessions? This year���s events have reminded us that recessions are unpredictable. And the government���s response has been patchy, with many (especially the self-employed) not getting the financial help they need. Which poses the question of how to ensure the government or Bank of England can get support quickly to everybody in the next downturn. The means of delivering helicopter money or people���s QE must be in place.

- How do we reform the tax and benefit system? Yes, there���s a case for land value tax. But the details are key: how to value land, what to do about people who are asset-rich but cash-poor and so on? Ditto lots of other tax changes, such as ending the bias towards corporate debt. The same���s true of benefit reform. Whilst a basic income is appealing, can we reconcile it with wide variations in personal needs and housing costs? In these questions, the experience of benefit users is crucial: how can we make the system as simple and quick as possible, so users do not face weeks without cash, or uncertainty and harassment, and how can we ensure that the transition from benefits to work is as smooth as possible?

- Why have real wages stagnated since the mid-00s, and how might this be reversed? The main reason is stagnant productivity rather than increased exploitation. And there are many likely causes of that stagnation. But how can we get productivity going again? Increased aggregate demand is part of the answer. So too is better training and management, stronger competition (included from overseas), more innovation and R&D and - yes- greater equality. But how to achieve these?

- What are the links between economic growth, institutions and values? We know from Ben Friedman���s work that economic growth increases tolerance and liberalism, so we need it to reduce the right���s ability to exploit culture wars; the left will win these by economic growth, not by being dragged onto the right���s terrain. Necessary as growth is, though, this does not suffice to get us to socialism. Some believe that this requires a change in values, towards more reciprocal altruism. But what institutions might promote such values? Failing that, how might we harness self-interest to promote socialism? How far can or should we promote decommodification, for example?

- How can we empower working people? We know that union membership and more autonomy improve worker���s well-being ��� which is great not only in itself but also because happier workers are more productive. But how can these be extended? Is a shorter working week also feasible? How else might job satisfaction improve?

- What corporate forms should government encourage? We���ve evidence that coops can raise productivity, and that a stock market listing can reduce efficient investment. Which poses the questions: how far can cooperatives be rolled out? What form should worker control take? What are the relative merits of regulation and nationalization in dysfunctional industries (I suspect there���s a stronger case for nationalizing banks than utilities)? How can nationalized industries be put under effective and democratic control? How far should outsourcing go, and should it be dominated by the usual suspects? Can procurement policy be used to encourage coops? I���m not sure there are general answers here. Context is everything.

- How might we best achieve value for money in the public sector? We all know that the only binding economic constraint upon fiscal policy is inflation. But there might come a time when this constraint bites. So efficient public spending matters. But how can we ensure that government procurement isn���t dominated by cronyism? How can we empower public sector workers to identify waste and improve efficiency?

- How can we best promote green growth? We know we need it. But what are the mechanisms? How do we best encourage green R&D and innovation? What���s the role of taxes and subsidies?

You might reply here that we know some of these answers. Maybe. But politics isn���t only about ideas. It���s about what ideas get mobilized and which side-lined. The point of such an exercise is to increase the salience of these policy areas ��� to ensure that they, and not the passing faff of newspaper headlines, form the agenda. This requires a form of message discipline from Labour MPs - to stick to issue that matter and not respond to media froth.

What���s more, abstract centralized knowledge of principles is not enough. We need detail and ground truth. And this comes from mobilizing not just academic experts, but local experts ��� those with hard experience of getting benefits, working in the NHS, setting up a small firm and so on. Hence the need for widespread, bottom-up deliberation.

This might seem technocratic stuff. And God knows we need that. But it���s a different sort of technocracy. It���s not the bullshit managerialism of New Labour, but a genuine drive to harness local expertise. Ground truth is everything.

But it���s more than that. What all this amounts to is a different way of doing politics. It sets the agenda. It says: our focus is upon real, material living standards, and we must resist distractions from this. It also says that policy is to be developed not with regard to fleeting newspaper headlines but to hard empirical evidence. Policy is not something to be pulled out of your arse or a newspaper column.

The aim of this exercise should be to marginalize the likes of Kuenssberg and Peston, as well as all those centrists and right-wingers who think that politics is about the voices in your head rather than the ground truth of living standards. The message to these should be: you are irrelevant.

Now, it should be obvious that my point in saying all this is not to offer advice to Starmer but rather to highlight how a different politics is possible, and how Westminster-centric politics is a trivial distraction from material truths. In an age of stupidity, the pursuit of expertise becomes a revolutionary act.

November 4, 2020

Farage's dangerous appeal

Nigel Farage���s effort to rebrand the Brexit party as an anti-lockdown faction poses the question: what���s the link between being pro-Brexit and anti-lockdown?

It might seem there���s none. Sure, anti-lockdowners are proclaiming the virtues of freedom. But the anti-migrant sentiment Farage stirred up during the Brexit referendum is the antithesis of libertarianism. If we put it nicely, Reform UK is an unstable coalition between cultural conservatives and libertarians. Less nicely, it���s just another toxic grift.

Perhaps, though, there is a common theme between hostility to migrants and the lockdown. It lies in something Richard Sennett wrote fifty years ago in The Uses of Disorder. Social life, he said, is a process of awkward encounters not just with other people but with a reality that is other than we���d like it to be. Many people cope with this by developing a ���purified identity��� that denies dissonances and discomfort:

The threat of being overwhelmed by difficult social interactions is dealt with by fixing a self-image in advance, by making oneself a fixed object rather than an open person liable to be touched by a social situation.

Such a self-identity, said Sennett, is ���a fearful defence against the unknown future��� which arises from ���a fear of the sources of human diversity that create history.���

Farage���s reaction to feeling ���awkward��� on hearing foreign languages on a train exemplifies this. It was not to celebrate the freedom that people have to come to the UK, nor to wonder what benefits diversity brings. Instead, it is to resist such migration. His fixed identity must have priority over dissonant reality. (We might add that this fits Perry Anderson���s idea of ���imagined communities.��� As Sennett says, ���the myth of community solidarity is a purification ritual.���)

In the same way, rather than see the lockdown and mask-wearing as the price we must pay to combat the virus, Farage resists it. He wants to screen out dissonance and assert the priority of his preferences over the imperfect solution to a collective action problem. This is the attitude of a narcissistic toddler throwing a tantrum because he is unable to accept that the world is not as he wants it to be.

To put this point into sharper focus, we can contrast this to two other attitudes. One is expressed in Dar Williams��� astounding song After All. ���Once upon a time I had control and reined my soul in tight��� she sings. This purified identity however led her to the brink of suicide. But, she continues:

Cause when you live in a world

Well it gets in to who you thought you'd be

And now I laugh at how the world changed me

Our fixed identity can jeopardize our mental health. Throwing it off and embracing dissonance enables personal change and growth ��� and survival.

But the hatred caused by dissonance need not always be channeled inwards. It can also be directed outwards. Noreena Hertz, following Hannah Arendt, argues that loneliness and isolation, and an inability to engage with the world as it is, fuels populism. Farage is tapping into this, and not in its most toxic form: think also of ���incels��� and perhaps Islamist terrorists.

My second point of contrast is with Friedrich Hayek. The thing about freedom, he said, is that we cannot foresee its benefits:

Since the value of freedom rests on the opportunities it provides for unforeseeable and unpredictable actions, we will rarely know what we lose through a particular restriction of freedom. Any such restriction, any coercion other than the enforcement of general rules, will aim at the achievement of some foreseeable particular result, but what is prevented by it will usually not be known. (Law Legislation and Liberty Vol I, p56-57.)

If we are to truly embrace freedom, with the benefits it brings (many of which are non-economic) we must therefore be prepared to tolerate some disorder, sights and sounds that some fixed identities would resist ��� be it foreign languages on a train or same-sex couples dancing on Strictly.

Which brings me to a paradox. The right sometimes accuse students and the left of being ���snowflakes��� ��� of having a Sennettian fixed identity which seeks safe spaces against uncomfortable interactions. Maybe this is right, maybe not - though as I am past the age of 21 student politics no longer interests me. Such an accusation, however, applies just as much to many on the right. And perhaps it does more social damage there.

October 30, 2020

"A great deal of ruin"

���There is a great deal of ruin in a nation��� wrote Adam Smith in 1777, suggesting (possibly) that countries can cope with poor policies. These are wise words, in many contexts.

Take for example, the NAO���s claim that there is ���likely to be considerable amounts of fraud and error��� in the government���s furlough scheme and the Resolution Foundation���s estimate that the government has paid around ��1.3bn to self-employed workers who in fact suffered no loss of income. No doubt this is sub-optimal, an element of ruin. But this is not in itself a decisive objection to the schemes. It was essential that people hit by the lockdown got quick support. And as the old saying goes: ���Good, fast, cheap: choose two.��� In choosing ���fast���, the government sacrificed a little ���cheap���. It incurred some ruin. But this, I think, was a reasonable choice*.

To take another example, Tory MP Ben Bradley has claimed that free school meals vouchers are ���effectively��� a handout to a crack den and brothel. Even if this is true ��� and the evidence for it is less than overwhelming ��� so what? It is impossible, except at colossal administrative cost, to target help to the deserving poor and only the deserving poor. The question is what ruin do we want to incur ��� that of some help going to crack dealers, or that of some children going hungry? Many of us would prefer to err on the side of the former ��� and in an imperfect world we must err.

Economic policy entails trade-offs ��� a fact which holds even if there is no binding constraint (yet) upon government borrowing. For example, a small welfare state might incentivize people to find work, but it also imposes greater cyclical risk upon workers and indeed businesses. Or a vibrant market economy entails economic and social instability. We cannot avoid some element of ruin. Sometimes, we must choose which type of ruin to incur.

There���s another form of ruin ��� ignorance. Michael Story and Stuart Ritchie describe how experts were initially wrong about Covid-19, for example in resisting the use of masks and calls for an early lockdown. Again, though, this form of ruin is inevitable: the world is complex and unknowable. We must choose which errors to make, what ruin to incur. Where we might justifiably blame the experts is not so much for being wrong but for exaggerating their knowledge.

And where knowledge is unobtainable ��� as it often is about the future - optimization is futile. We can only satisfice ��� which entails (with hindsight) waste, or ruin.

All this applies to policy-making. But it is not just states that contain a great deal of ruin. So too does the private sector ��� as anybody who has worked in it will know. Nick Bloom and John Van Reenen have shown (pdf) that in all countries there is ���a long tail of extremely badly managed firms.��� Competition does not eliminate inefficiency. Ruin remains.

This is not just because there are all sorts of obstacles to strong effective competition such as excess regulation or rent-seeking. Even where competition is strong and incentives to succeed are sharp, people fall short of optimality. We know this from the economics of sport. NFL teams have punted too much (pdf) on fourth downs; ice hockey teams don���t replace their goalminders often enough when they are trailing; and golfers don���t put as much focus (pdf) into birdie putts as par ones.

Markets are a great technology. But they are not the devices for achieving optimizing that simple-minded Econ101 tells us.

We must not, however, think that ruin is necessarily a bad thing. It���s not. There���s a trade-off between optimization and resiliency. Redundancy (ruin) can give us the flexibility to respond to crises**. Had the NHS had more beds and doctors before Covid struck, it would have coped better ��� but at the expense of ���wasting tax-payers��� money��� in normal times. As Jo��o Ferreira do Amaral wrote (pdf):

There is I think a good case for keeping a system flexible to cope with surprise even if this mean more uncertainty and less efficiency.

There is, though, another form of ruin, of imperfection ��� the trivial fact that there are so many idiots in the world. It���s tempting to try to engage with these. But often wrong. As Tim Harford has shown, myth-busting often doesn���t work. Mill was wrong: wrong opinions do not ���gradually yield to fact and argument.��� In many cases ��� where the opinions are those of obscure cranks ��� we should just ignore them. Haters are gonna hate and twats are gonna twat.

Not only is it better for the level of debate if we recognise that there is a great deal of ruin in a nation, but it���s probably also better for our mental health as well.

* In fact, it also sacrificed some good. The RF points out that lots of hard-hit self-employed got nothing. For me, this is a less forgivable error.

** The converse is also true: in 2008 banks went bust because of their "optimized" portfolios.

Chris Dillow's Blog

- Chris Dillow's profile

- 2 followers