Chris Dillow's Blog, page 22

April 2, 2020

Inequality, morals & Marxism

One thing this crisis is demonstrating is that there are plenty of bad employers: the Guardian and Labour List both have lists of them. Another is that, as Sarah O���Connor says, ���the people we need the most are often the ones we value the least.��� As Paulo dos Santos says, society ���grossly undervalues��� care work and other jobs essential to fighting the pandemic.

Both these facts show the need for a Marxian perspective.

First, we must ask: why are care workers and others so underpaid? It is certainly not because they lack moral desert. Nor is it because they lack skills: caring demands immense ���soft skills��� such as patience, discipline and an ability to get on with people as well as physical ones. From a purely technical point of view ��� that is, one divorced from socio-economic factors ��� it would be cretinous to claim that a nurse is less skilled than the grifter opinion-mongers who pollute the media.

Instead, care workers are badly paid because they lack power. Some of this is the result of longstanding norms: work done by women and immigrants has long been stigmatized, devalued and regarded as ���unskilled.��� But another part of it is simply a lack of outside options and hence of bargaining power. As Paulo says:

Market wages and conditions reflect the precarious social positions and sometimes utter desperation of those who typically perform them.

The point, of course, broadens. As Rick said, ���all pay is, ultimately, a function of power.��� It is trivially true that labour is the source of value, as this lockdown is reminding us. But how that value is distributed depends upon power. Your ���skills��� are only one element in your power: parlaying these into a decent income is another matter.

Power also lies behind the fact of bad employees. Big firms have a degree of monopoly power: they wouldn���t be profitable if they did not. Good employers use this power to share rents with workers. Bad ones, however, use their monopsony power to jack up the rate of exploitation.

What should be done about this? Some leftists think we need to make a moral case for paying key workers more and that we need to shame bad employers into improving.

Moral exhortation, however, might work sometimes but it is not enough. We do not reduce burglary or murder merely by appealing to criminals��� better nature. We use force as well. Similarly, we won���t abolish poverty pay and bad working conditions merely by asking nicely.

We must instead realize, as Marxists do, that material conditions matter. As the late great Norman Geras wrote in his essay Marxism and Moral Advocacy, ethical analysis and advocacy:

Need to be done with some thought for the social and material conditions of attaining any given ideals, the means of and agencies for attaining them, [and] the social interests and movements that can conceivably be coupled with or become attached to the ideals and imperatives in question.

It is easy to see how we might abolish the material conditions that give rise to inequality, bad employers and poverty wages. Macroeconomic policy must be aimed at ensuring over-full employment. We need strong trades unions and a high citizens basic income to empower workers to reject bad pay and conditions. And government (and local authority) procurement should be used to encourage coops.

Most social democrats would agree with this. We Marxists, however, have two doubts.

The first concerns how to get there. How do we mobilize the social movements and interests that would deliver a government committed to these, and weaken those that would prevent such a thing?

The second is that these policies are only stepping stones, part of what Erik Olin Wright called an interstitial transformation (pdf). They will lead to a squeeze on profits. When this happened in the 70s, it led to a backlash against social democracy and to Thatcherism. The challenge is to ensure that it leads instead to socialistic forms of ownership. Historically, social democrats have resiled from this challenge.

This crisis has increased the salience of inequality and injustice. But there���s a huge distance between an issue being salient and it actually being properly addressed. We have little hope of closing this distance without a Marxian perspective.

March 29, 2020

The Tories' dilemma

Matthew Parris in the Times raises a challenge for Tories ��� but not, perhaps, the one he thinks he does.

The government���s willingness to borrow to get through the crisis, he says, undermines the traditional ���Conservative case for prudence in public spending.��� And if there are not the limits the Tories thought on public spending, then:

The Tories had better brace themselves serious questions about how we can do it for a virus but not to save a shipyard, or the planet from climate change. Or double the future capacity of our hospitals, or legal aid limits, or nurses and carers��� wages.

I think Tories have ��� and always have had - two answers here. But they contradict each other.

First, let���s dispose of bad reasons for ���prudence.���

In part, it is a legacy from different times. In the relatively closed economies of the 70s and 80s, there were limits on how much governments could borrow, set by inflation and savers��� reluctance to lend to the state. Although these limits haven���t been binding for a long time, it���s common for people���s ideas to outlive the reality behind them.

Also, the idea that government debt is a burden on future generations is wrong, and not just because they can roll it over to the next generation and because interest rates are negative. There���s plenty else that can impose a burden on our children. Recessions have scarring effects, both by reducing the skills and experience young workers acquire, and by making people more risk-averse (pdf) in later life. Equally, poor education and inadequate infrastructure depress people���s incomes in future. And a lack of action on climate change might be catastrophic for our grandchildren. Reducing the ���burden on future generations��� might as well justify increased government borrowing as lower.

Why, then, have the Tories had an instinctive (if not always realized) desire to limit public spending?

Simple. It���s because they want a large private sector. If there were no moral or prudential limits on government spending, they fear, the state would expand at the expense of the private. Voters do not instinctively favour a market economy.

One reason why the Tories want a large private sector, of course, is that they are the party of capitalism, and capitalism is about making profits.

This explains why their belief in ���prudence��� has waxed and waned. Sometimes ��� as in the early 80s - austerity is needed to depress wages and so relieve the squeeze on profit margins. But at other times, such as the early 90s and now, capitalism requires increased public spending to shore up legitimacy, compensate for weak private sector demand, or provide the infrastructure that capitalism needs.

But there���s a second reason why Tories want a thriving private sector. It���s that this can sometimes deliver the goods.

The USSR put a man into space but couldn���t give its citizens comfortable shoes. Which shows the strength and weakness of the state. It���s good at achieving single agreed-upon objectives such as winning wars or (we hope) defeating viruses: there are no libertarians in foxholes. But it���s bad at delivering a variety of goods or at innovating to improve the quality of those goods. For this, we need a market economy.

It���s not just material goods that a market economy delivers, some Tories think. Following McCloskey and Montequieu, some believe in ���doux commerce��� - that commercial society inculcates virtues. They believe that success in markets requires an understanding of what others want, sobriety, prudence and the cultivation of good reputation.

Herein lies the real problem for Tories. These two cases for a large private sector can conflict with each other. ���Doux commerce��� requires constraints upon capitalists. As Jesse Norman writes in Adam Smith: What He Thought and Why it Matters:

Markets are sustained not merely by incentives of gain or loss, but by laws, institutions, norms and identities, and without those things they cannot be adequately understood.

Profit maximization, however, sometimes requires that these institutions and norms be ripped down, the better to pursue rapacious exploitation, monopoly, and cronyism. You can interpret that much-abused term ���neoliberalism��� as the process whereby ���doux commerce��� is supplanted by a harsher form of capitalism ��� in which we lose the James Timpsons and get the Mike Ashleys.

In this process, says Jesse:

Business activity loses any relation to, and often clashes with, the public interest;���business merit is separated from business reward. These features then feed off and into a culture in which values of decency, modesty and respect are disregarded, and short-termism and quick rewards come to dominate long-established norms of mutual obligation, fair dealing and just reward.

It's not just in the realm of morality that there���s a conflict between capitalism and commercial society, however. There���s also a conflict in economics. A genuinely thriving free market would see few concentrations of private wealth or power, because competition and creative destruction would eliminate them. American leftists have the slogan ���every billionaire is a policy failure���, but it would be equally true to say that every billionaire is a market failure.

Herein, I suspect, lies the biggest dilemma within conservative thinking. It does not concern their attitude to ���prudence��� in the public finances: it is sometimes correct to suspend such prudence. Instead, their problem is: why do they want a large private sector? Because there is a conflict ��� which has grown markedly in recent years ��� between a healthy commercial society and more exploitative forms of capitalism.

We might wonder why this dilemma is not more publicly discussed. One reason, I suspect, is that here we have another example of an idea outliving their material base. In the mean and nasty 70s, it was plausible that there was little tension between these two conceptions of a market economy; one could believe that more capitalism would mean doux commerce. It is, however, less plausible now. Another reason, perhaps, is that the Tory party has, in one respect at least, an emergent intelligence that Labour lacks: it knows instinctively that some issues should not be raised.

March 27, 2020

Another wasted crisis?

In the immediate aftermath of 9/11 there was much talk that the real heroes were firemen rather than hedge fund managers. That talk soon disappeared, and Americans��� indulgence of plutocrats continued as normal. This warns us about clapping for carers: it might prove to be a brief emotional spasm with no lasting social effect.

Yes, crises can be turning points. But those of the 1970s and 2008 tell us that, for the left, they can also be wasted opportunities.

Here are five uncertainties about how the legacy of this one.

Will the crisis shift politics in a more technocratic direction?

It has taught us that we need more spare capacity in the NHS and that the government has prioritized static ���efficiency��� too much at the expense of resilience. It���s also taught us that the we need to build a welfare and monetary policy infrastructure so that help can be funnelled quickly to those in need ��� for example, ensuring everybody has a bank account so that helicopter money can be delivered immediately, or ensuring that people don���t face long waits and Kafkaesque bureaucracy when claiming benefits. Yes, this crisis was sudden and unpredicted, but so were previous recessions. We need the means to respond to them quickly.

In short, what we need are technically competent politicians focused on improving state capacity.

But will we get this? I had hoped that the Grenfell catastrophe would drive politics in this direction, I was wrong. The fact that people could vote Tory and then clap for carers a few weeks later shows that too many have forgotten (if they ever knew) that politics should be about collective action and regard it instead as a TV gameshow. And there are powerful forces entrenching such a conception, such as Bayesian conservatism and the incumbent grifter media.

Will the crisis increase global cooperation?

Gordon Brown says it shows the need for a global effort to produce vaccines and medical supplies and for global support for emerging markets, whose economies might well be hardest hit. But on the other hand, the Orange Imbecile���s talk of the ���Chinese virus��� shows that the crisis is also stoking up crude nationalism. Robert Shrimsley says it could provoke ���a new emphasis on self-sufficiency��� with protectionism and subsidies for farmers and key manufacturers.

How will the crisis change attitudes to risk?

We know, not least thanks (pdf) to the work (pdf) of Ulrike Malmendier, that recessions can have scarring effects. Memories of them can make us more cautious (pdf) even years later.

The political manifestation of this is, however, uncertain. On the one hand, we might hope that an awareness of one���s vulnerability to unemployment might increase demands for redistribution: support for the post-war welfare state was founded in part upon memories of the Great Depression. But on the other, it was (in part) the people who suffered from unemployment in the 80s who handed the Tories their election victory last year.

What���s more, scarring isn���t the only mechanism. There���s also a framing effect. This time next year we���ll be seeing the economic damage done by post-Brexit trade barriers. But these will look small compared to the drop in output we���ll see in the next few weeks and they will therefore seem tolerable to some. A lot of ERGers will be saying ���we got through the coronavirus so we can get through this.���

What���s the future of fiscal policy?

One lesson of the crisis is that western governments have much more fiscal space than austerians pretended. And as it���s likely that borrowing costs will stay negative and tax revenues will recover as the economy normalizes, there should be no urgency to cut borrowing much.

But on the other hand, some Tories might see the higher debt-GDP ratio as a pretext for demanding more spending cuts.

How will the crisis change the balance of class power?

James Meadway says a retreat from globalization and workers���s ability to withdraw labour on public health grounds should shift this balance ���dramatically back in favour of labour��� ��� especially if we also get a universal basic income.

But higher unemployment will have the opposite effect. And just as memories of the Great Depression squashed wage militancy for a generation ��� it only re-emerged in the 60s when workers with those memories started to retire ��� so might memories of this crisis cow labour too.

All of this is deliberately inconclusive. As Jon Elster said, the social sciences are a toolbox of mechanisms which sometimes help us explain without being able to predict. There is little inevitability in human affairs. Those of you who want this crisis to lead to a better world need a lot more than gestures and hope.

March 20, 2020

Against "aggregate demand"

One legacy of the 2008 crisis has been that firms have built up big cash piles. Bank of England data show that non-financial firms now have over ��425bn of sterling deposits. That���s equivalent to over two months of GDP and over 12 months of profits. You might think this is a great comfort, as it suggests that companies can respond to their loss of revenues not just by borrowing but by simply running down these cash piles: isn���t that what they are for?

But, but, but. There���s a huge problem here. The firms suffering the biggest drops in cashflow might well not be those with the cash mountains. To the extent that the two groups differ, there will be genuine distress.

Which alerts us to a fact overlooked by basic macroeconomics. The economy does not comprise a ���representative agent��� firm supplying ���aggregate demand.��� Instead, it comprises tens of thousands of different ones, with very different balance sheets (even within the same industry) supplying different goods, who respond differently to changes in economic policy.

This is not a trivial fact. It matters enormously. A given fall in ���aggregate demand��� which hits cash-strapped firms will be much nastier than one that hits cash-rich ones. We can have no confidence that this crisis will see the latter happen.

Also, as Daron Acemoglu has shown, recessions can be a story of the interconnections (pdf) between firms. The 2008 crisis was so bad in part because banks were key hubs in networks, so when they cut supply everybody suffered.

Networks could amplify this downturn. If a firm fears its customer will go bust, it���ll not supply it on credit and so it might well fail: in this way, expectations can be self-fulfilling. Equally, one way in which multiplier effects work is that one firm���s failure and one worker���s redundancy (or, importantly, one freelancer���s lost contract) depresses demand for others.

There���s another problem. Let���s say you buy a coffee every morning on your way to work, but you then work from home for a month. You won���t buy 26 coffees on your day back in the office. But you will have over ��50 more to spend on something else. The losers from this downturn will not therefore necessarily be the same as the winners from the upturn. Even if the macro data show a V-shared recovery, the ground truth will be that the upward leg of the V is different from the downward leg.

This wouldn���t matter much if capital and labour were fungible ��� if, say, car manufacturers could easily switch to making ventilators. But they are not. Instead, as Banerjee and Duflo point out in Good Economics for Hard Times, economies are ���sticky.��� Resources cannot switch from one job to another. The pit closures of the 80s and 90s, for example, led to longlasting unemployment and poverty, contrary to the just-so fairy tales of Econ101ers.

Which raises a problem. If unemployed waiters and bar staff cannot easily shift to become (say) the construction workers needed on the government���s new infrastructure projects then we might see unemployment co-exist alongside labour shortages.

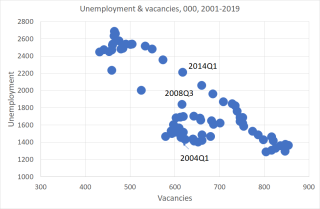

This is a common effect of recessions. They don���t just cut ���aggregate demand��� but shake up the pattern of it. My chart shows this. It plots the Beveridge curve ��� the link between unemployment and job vacancies.

As you might imagine, many points lie on a downward-sloping line: in recessions we are at the top-left, with high unemployment and low vacancies, and in good times we���re at the bottom right, with low unemployment and lots of vacancies.

But look at the vertical line in the middle of the chart, where vacancies are around 600,000. In 2004, this level of vacancies coexisted with unemployment below 1.5m. By 2008, however, the same level of vacancies existing alongside unemployment of 1.8m, and by 2014 with unemployment of 2.2m. This tells us that the crisis created a greater mismatch between labour demand and supply.

And we���ve not recovered from it. Those points in the middle of my chart below the main curve all depict the pre-crisis years. Since the crisis, we���ve moved down the curve, but the curve has stayed further out than it was pre-crisis.

There���s a danger that this recession will shift the curve even further out, causing unemployment to coexist alongside vacancies.

Which would mean that the unemployed won���t even serve the interests of capital because they���ll not bid down wages: unemployed baristas in London would compete against construction workers in the north.

Now, this might not be a severe problem for capital if immigration adjusts, so that we replace one group of migrant workers with another, as baristas return to Poland whilst construction workers come over.

But this is unlikely to be the whole story. Which is why there is an overwhelming case for stopping firms laying off workers in this crisis. The case is not just a humanitarian one, but an economic one; the workers who lose their jobs won���t easily find new ones, and won���t even be a decent reserve army of labour.

March 18, 2020

Against one-trick ponies

Those of you who believe that bourgeois economics is mere ideology have had two data points of corroboration recently.

First, Stephen Moore, Art Laffer and Steve Forbes said: "don���t expand welfare and other income redistribution benefits like paid leave and unemployment benefits that will inhibit growth and discourage work."

This contain layers of nonsense. For one thing, during the current public health crisis we want to discourage people from working so they don���t infect others. But even in normal times. Their statement would be wrong. In one survey of the evidence Abhijit Banerjee and Esther Duflo conclude that ���there is no evidence that cash transfers make people work less.��� (Good Economics for Hard Times, p289). One reason for this is suggested by the fact that the unemployed are much unhappier (pdf) than a lack of income alone would predict: work is a source of meaning and identity.

The second piece comes from ECB council member Robert Holzmann who claimed that the virus might ���release positive cleaning forces.���

It is true that some recessions (pdf) can sometimes have this effect. If aggregate demand falls, people are likely to cut spending on the goods and services that offer worse value, which are likely to come from the worst-managed firms. And capital scrapping can raise aggregate profits and so spur future investment. But it���s obvious that this recession is not one of these cases. The hardest-hit firms will be those most hurt by lockdowns such as pubs and restaurants. These are not necessarily the least efficient or profitable ones.

What we have here, then, are two especially egregious examples of an error which Dani Rodrik warned us against (pdf): we must not impose the same model upon every problem. Instead, we must have a variety of models or theories and apply the right one in the right place. Economists cannot be one-trick ponies ��� especially when as in Laffer���s case, that trick is a lousy one.

In this sense, there���s a big difference between these rightists and we Marxists. As I���ve said, many of us are unideological about many matters (such as the impact of minimum wages) because we���ve no dog in those fights.

This is true of crises. Although Marx held the ideological (and correct) view that capitalism was inherently prone to crises, he saw that these would take many different forms. As one of the earlier and better of his commentators put it:

Crises are extraordinarily complicated phenomena. They are shaped to a greater or less extent by a wide variety of economic forces���the actual economy [is] so much more complicated than the model systems which were analysed in Capital (Paul Sweezy, The Theory of Capitalist Development, p133)

It should be obvious to anyone who isn���t an ideologue that a public health crisis, and the attendant economic crisis, requires a greater degree of state intervention than would be appropriate in normal times. Just as there are no atheists in foxholes, nor are there any intelligent libertarians.

The smarter people on the right get this. ���Treating this event as a normal market adjustment seems perverse��� says Ryan Bourne. He says the aim of policy should be to

mitigate distress among vulnerable households and businesses, preventing business failures or mass layoffs in viable firms, or severe hardship for those without significant savings or employer benefits.

���Paying people not to work���, he says, ���becomes, for the time being, a virtue.���

He would put far more stress on those words ���for the time being��� than many of us on the left would, who favour more redistribution and automatic stabilizers even in normal times. This, however, should be a debate for another time. The fact is that what���s appropriate in a crisis might not be appropriate in normal times*. Today, the distinction is not between left and right, but between those who get this and those who don���t.

* This is true in another sense. A universal basic income and/or helicopter money are, I suspect, good ideas for the future, but not so appropriate today.

March 12, 2020

Winning the argument?

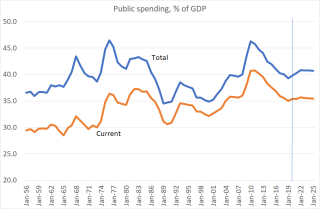

The reaction of many on the left to the big spending rises in yesterday���s Budget is that they show that Labour has ���won the argument��� for higher public spending. This is partly true.

On current plans (pdf), total public spending will rise to 40.8% of GDP by 2024-25*. That���s a bigger share than Labour spent between 1997 and 2008. The Tories��� justification for this is correct: low borrowing costs make it sensible to borrow to support economic growth and improve our infrastructure. But this is exactly what most on the left ��� as well as mainstream macroeconomists - were saying years ago. In this sense, the left has won.

In another sense, though, this is awkward for the left. It tells us that the Tories can increase spending at least as much as Labour can. One reason for this is the old clich�� ���give a man a reputation as an early riser and he can sleep til noon.��� The Tories can raise spending a lot for the same reason that Nixon could pursue d��tente. Their (wholly unjustified) reputation with the media and voters for sound stewardship of the public finances means they can better get away with raising spending. Whereas John McDonnell���s promise of ��500bn of infrastructure spending was portrayed as reckless, Sunak���s ��600bn is ���the road to riches��� and a ���bold battle plan���. Yes it���s unfair, and appalling double standards. But this is the world we live in.

if we identify leftism with higher public spending, the Tories do leftism better than Labour.

But of course, we should not identify the two. There are still at least five big differences between the Tories and the left:

1. Day-to-day spending. Although Sunak has stopped cutting, he's not reversing Osborne's cuts, as Simon points out. That increased share of spending in GDP owes a lot to more spending on the NHS and pensions. This suggests that plenty of other areas of spending, such as by local authorities, will remain under pressure.

2. The environment. Freezing fuel duty and building more roads will give us more cars and pollution. Sunak might have been converted to fiscal common sense, but this Budget was not the Green New Deal.

3. Income equality. This Budget fell way short here. As Aditya says, it failed to raise sick pay or extend it to gig workers. And as the Resolution Foundation says in its excellent assessment (pdf), ���this Budget was silent on arresting ongoing welfare cuts��� ��� cuts that will increase income inequality. Yes, Sunak promised cuts in NICs and a higher minimum wage. But as the IFS points out, these are not especially egalitarian:

Only 8% of the gains from the NICs cut would accrue to the poorest fifth of working households. And only 22% of minimum wage workers live in the poorest fifth of all households.

4. Economic institutions. There is, though, more to inequality than incomes. Genuine equality requires more equality of power, and breaking the dominance of the ultra-rich (pdf). Which requires institutional change. As James Meadway has said, this means that ���ownership and control of productive resources��� should be decentralised, democratic, and collective as far as possible.��� Worker ownership should be a key part of any leftist platform.

5. Productivity. The Tories��� conversion to the idea that infrastructure spending can raise productivity is welcome. But we need more than this. The OBR estimates that the rises in government investment spending will, if sustained, eventually raise productivity by 2.5%. But this is only a fraction of the productivity shortfall we���ve suffered since the crisis: if productivity had grown as much since 2007 as it did in the 40 years up to then, it would now be 22 per cent higher than it actually is. Boosting productivity requires far more than public spending. Whilst some of these things should be compatible with Tory sentiments ��� such as tougher competition policy ��� others might not be, as such as shifting taxes onto landlords, pursuing a softer Brexit** or fighting workplace inequality and cronyism.

So yes, the left has won the argument on public spending. But there is much more to leftist economics than spending. And these arguments are far from won.

* My eyeball econometrics suggests there are upward trends in my chart. Maybe Wagner���s law still holds.

** The OBR says we have so far suffered only one-third of the total adverse effect of Brexit on productivity.

March 10, 2020

On (un)predictability

It���s a clich�� that stock markets have been in panic mode recently. But why? The answer is not as obvious as you might think. And the issue matters not just for equity investors but for everybody interested in social science.

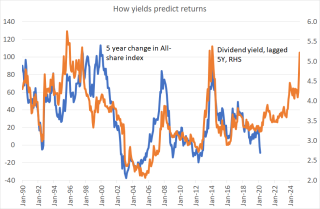

My chart shows the point. It shows that the All-share index has been largely predictable simply by the dividend yield. Since 1985 the correlation between the yield and subsequent five-year changes in the index has been a humungous 0.8. With the yield now over 5%, history suggests we have the best buying opportunity since 2009.

But, but, but. If investors had believed that the dividend predicts returns, we would never have seen any significant sell-offs of the sort we���ve seen lately. Any incipient rise in the yield would have triggered buying with the result that the yield and prices would have been stable. The pattern in my chart exists only because people didn���t believe it would exist.

Why, then, has the yield been so volatile?

One answer is that it only predicts medium-term returns. Most stock market participants, however, don���t care about these. For many, ���the long-term is this afternoon.��� Over shorter periods, returns are unpredictable: the correlation between the yield and subsequent monthly returns has been only 0.1. A cheap market can get cheaper ��� hence the saying, ���never try to catch a falling knife.���

In the short-term, participants focus on two things other than the dividend yield.

One is trying to anticipate others��� beliefs. As Keynes put it:

Professional investment may be likened to those newspaper competitions in which the competitors have to pick out the six prettiest faces from a hundred photographs, the prize being awarded to the competitor whose choice most nearly corresponds to the average preferences of the competitors as a whole; so that each competitor has to pick, not those faces which he himself finds prettiest, but those which he thinks likeliest to catch the fancy of the other competitors, all of whom are looking at the problem from the same point of view. It is not a case of choosing those which, to the best of one���s judgment, are really the prettiest, nor even those which average opinion genuinely thinks the prettiest. We have reached the third degree where we devote our intelligences to anticipating what average opinion expects the average opinion to be. And there are some, I believe, who practise the fourth, fifth and higher degrees.

This means we face what Mordecai Kurz has called endogenous uncertainty ��� uncertainty not just about the so-called fundamentals, but about other investors��� beliefs (or their beliefs about others��� beliefs and so on).

A second concern in the danger of a positive feedback loop, whereby falls lead to further falls. These can arise simply because leveraged traders, facing big margin calls, are forced to sell. Or they are the result of ���risk parity��� trades, whereby traders trying to maintain stable volatility in their portfolios sell stocks when volatility rises. (This isn���t as daft as it seems).

Of course, not all uncertainty is generated only within financial markets. Some exists because the world really is unknowable. What investors must worry about is not merely the central case scenario but the distribution of risks. As David Meenagh and colleagues have shown, small but reasonable changes in the probability we attach to a catastrophe can justify big swings in prices.

In this context, my chart overstates the predictability of share prices. For decades, the UK stock market has recovered from most setbacks*: we���ve enjoyed what Dimson and Marsh called the triumph of the optimists. Disasters have not materialized and it has therefore paid off nicely to buy when investors have worried about them.

But we have no assurance whatsoever that history will repeat itself. Instead, we face what Richard Bookstaber called radical uncertainty ��� the unknowable chance that the past won���t be a guide to the future. Returns might be non-ergodic.

It���s reasonable to worry about this now. As Paul Krugman says, ���markets are implicitly predicting not just a recession, but multiple years of economic weakness.��� With conventional monetary policy almost maxxed out, central banks can do less than before to support equities. Covid-19 might accelerate deglobalization and the productivity gains it has brought. The low aggregate rate of US profit might ensure continued secular stagnation. ���Sticky��� economies (to use Banerjee and Duflo���s useful term) cannot adapt well to shifts in the pattern of demand wrought by Covid-19. And so on.

Sure, a high yield in the past has been a predictor of high returns. But it might today instead be a predictor of low profit growth. And even if it isn���t, it would be imprudent to bet the house this way.

We have known since Shiller���s work (pdf) in 1981 that share prices are more volatile than underlying dividends. What���s not so certain is whether this is because investors are irrational or not.

Now, I know a lot of you aren���t interested in stock markets. Insofar as they are full of pompous posh white men, I share your lack of interest. But there���s more to them than this. Markets raise questions of general importance: is there predictability in human affairs? Is history a guide or not? How do beliefs not only reflect the world but shape it too? Does the pursuit of individual incentives lead to efficient aggregate outcomes or not? What are the roles of rationality and irrationality? Markets matter not because of a few points here or there on the Footsie, but because they are a window onto the social sciences.

* Not all, though. The market is lower than it was during the tech bubble of 2000.

March 7, 2020

On centrist decline

One of the BBC���s most successful comedy shows of recent years is Radio 5���s 6-0-6, wherein actors pretending to be football fans phone in to spout gibberish about the game. A recurring trope is the need for ���passion���: managers are expected to be passionate, and teams lose because they ���didn���t want it enough.���

I was reminded of this by a tweet from Andrew Adonis, that Labour must ���get real about winning��� ��� as if the party would win elections if only they wanted it more.

This is yet another example of one of the great political changes of my lifetime ��� the utter intellectual collapse of the Labour right.

Think back to the mid-90s. Blairism ��� lest we forget - was at the time a genuine intellectual project, an attempt to accommodate (mild) social democracy to the economic realities of the time. So, for example, tax credits were intended to help the low-paid and boost work incentives in the face of weak demand for unskilled work: the minimum wage was in part a way of limiting the fiscal cost of such credits. Expanding universities was a way of meeting the increased demand for educated workers (as signalled by the rising graduate pay premium) whilst also capping inequality. Fiscal rules were an attempt to reassure bond markets: real long-term yields were then over 4%. And such rules, along with central bank independence were intended to reduce policy uncertainty, thereby encouraging investment.

This programme had its flaws but it was intellectually serious.

Today, though, the economy has greatly changed and poses different questions. What should we do now the inequality which matters is not so much the 90-10 ratio as it was in the 90s but the high incomes of the 1% or 0.1%? Is inequality really only a matter of income but also of ownership and power, and if so what should be done about this? What (if any) adverse effects does inequality have and how might we mitigate them? What should macroeconomic policy be when real interest rates are sharply negative? What should we do about unaffordable housing? How can we restart productivity growth? How can we ensure macroeconomic stability given that we learned in 2008 that stable macroeconomic policy alone is insufficient?

To questions such as these centrist politicians and pundits (most of the latter having not lost their jobs) have no answer. They have learned nothing since 2007. Neither Chris Leslie���s ���manifesto��� nor CUK���s launch document contained any meaningful economics at all. As Phil says, they offer ���not one scintilla of policy, or rumour of an alternative to Corbynism.���

Labour���s election defeat might have been the ideal opportunity for centrists to reassess Corbynomics and to question its critique of capitalism. But for the most part they have not done so. Far more of the reaction to that defeat has been to ask how Labour might better do retail politics, or how it might accommodate itself to socially conservative voters. What discussion of Labour���s economic policies there has been has focused upon its lack of appeal to voters rather than upon any intellectual defects in it. Of a centrist alternative to Corbynomics there is little sign.

This is not entirely for want of resources. You could put together a reasonable economic platform from the work of folks like the Bennett Institute, Radix or Sam Bowman and Stian Westlake. Instead, all we get is vague talk of electability and endless amounts of punching left.

Of course, we should not see politics merely as a matter of technocratic policies ��� and still less, in postmodern capitalism ��� as delivering real solutions to real problems. Centrists, for all their talk of being evidence-based rationalists, are as tribal as the rest of us. Hatred of the left is the premise of their thinking, not the conclusion.

Politics is also, of course, about class. And herein lies a problem for centrists: what is their class base supposed to be? Blair succeeded by forming an alliance of the low-paid; businessmen alienated by the Tories economic incompetence; and public sector workers.

But where is the equivalent today? Labour have captured workers alienated by high house prices and the neoliberal managerialism which New Labour accelerated. And the Tories have retirees and rentiers scared of redistribution. I suppose centrists could, if they tried, find a platform that appeals to the more progressive elements of capital and those workers who identify with them. But one lesson of Brexit is that such elements are insufficient.

Perhaps, then, the intellectual decline of centrism is a symptom of a decline in its client base. If so, then we have less to learn from Blair���s electoral successes than centrists pretend.

March 4, 2020

On capitalist stagnation

One of the problems with even the best journalism is that it reports day-to-day events without putting them into context, thereby telling us about the weather but not the climate. So it is with the news that ten-year Treasury yields have hit a record low.

Although the latest move is due to increased risk aversion triggered by the coronavirus this merely continues a long-term trend. Nominal yields have been trending down since the 80s, and real yields probably since it 90s.

Why? Standard explanations talk of the shortage of safe assets and global savings glut. Useful as they are, such explanations miss something important. This is that basic theory (and common sense) tells us that there should be a link between yields on financial assets and those on real ones, so low yields on bonds should be a sign of low yields on physical capital.

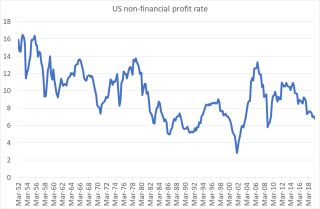

And they are. My chart shows that the profit rate for US non-financial companies has trended down since the 1950s. I���m not using fancy Marxian calculations here ��� though they tell a similar story. I���m simply using the Fed���s own numbers, expressing pre-tax profits as a percentage of non-financial assets measured at historic cost. Although this profit rate is higher than it was in the crises of 2000-01 and 2008-09, it is much lower now than it was in the 60s and 70s. And profits have never sustainably recovered from the crisis of the 70s and 80s. Even by their own lights, therefore, neoliberal policies ��� such as lower taxes, sharper CEO incentives, weak unions and a focus on shareholder value - have failed.

You might find this surprising. How can we reconcile it with the fact that, until a few days ago, the stock market was at a record high? Simple. For one thing, listed firms are an unrepresentative sample of all firms. They tend to be bigger and more monopolistic than the average ��� and the bigger ones among them are more profitable. And for another, the market���s high valuations reflect the hope that firms which are not very profitable (or loss-making such as Tesla) today will deliver monopoly profits in future. If we look past a few giant monopolies, the typical American firm has been struggling.

In light of this, three Big Facts make sense.

The first is the slowdown in productivity growth. Having risen by 2.2% per year in the 50 years to 2007, output per worker-hour has grown only one per cent per year in the last ten years. One reason for this (of several) is that lower profits reduce the incentive to invest and innovate. This is especially the case when low profits for many firms co-exist alongside monopoly power for a few, because monopolies prefer to entrench their power rather than innovate. Secular stagnation did not drop from the sky. It���s the product of trends within capitalism.

The second is capitalism���s vulnerability to crisis. To see this, imagine a different world in which there were abundant big profit opportunities for non-financial firms in the early 00s. The flow of savings from Asia would then have financed these cheaply. We���d thus have seen strong growth in the real capital stock and in productivity and profits (and maybe wages and employment too). But we didn���t, because there were few such opportunities. Savings flowed instead into housing and mortgage derivatives thereby stoking up a bubble which led to the crisis.

The third fact is documented by Anne Case and Angus Deaton in their new book, Deaths of Despair, wherein they show that, for middle-aged white people without much education, deaths from suicide, alcohol and drug misuse have soared since the 90s. A big reason for this is that employment opportunities for such people have worsened; even in today���s supposedly ���tight��� labour market, people without degrees are much less likely to be in work than they were in the 90s. And many of those who are in work are in worse jobs. Case and Deaton note that white men without a degree earn less in real terms than they did in 1979. Fewer and worse jobs mean a lower sense of self-worth, stress, family breakdown and hence deaths of despair.

But why have such job opportunities declined? It���s easy to blame globalization or technical change. But these are different ways of saying that it is no longer profitable for capitalism to employ less-skilled people at a decent wage.

The drop in bond yields is therefore one of the more innocuous symptoms of a dysfunctional capitalism.

Of course, all these trends have long been discussed by Marxists: a falling rate of profit (pdf); monopoly leading to stagnation; proneness to crisis; and worse living conditions for many people. And there is plenty of evidence (pdf) for them. The problem is, however, that many people want to shut their eyes to this evidence. In this sense, perhaps today���s two big stories ��� the record-low for bond yields and the success of Joe Biden in the Super Tuesday primaries ��� are related.

February 26, 2020

Incentivized stupidity

Two good things I���ve read this morning raise an under-appreciated point ��� that people can be incentivized to behave in ways that seem stupid.

First, there���s Tom Chivers��� review of Mervyn King���s and John Kay���s Radical Uncertainty. He says it is ���completely terrifying��� that they thought their book needed to be written, because economists and finance types shouldn���t need to be told that ���models are not 100% precise representations of reality.���

Of course, he's right. Models are unreliable and the historic data that goes into them might not be a guide to the future ��� points well made by Richard Bookstaber in The End of Theory and by Nicola Gennaioli and Andrei Shleifer in A Crisis of Beliefs. But investment bankers have indeed made precisely this error, most famously when Goldman Sachs��� David Viniar sais that during the crisis ���we were seeing things that were 25-standard deviation moves, several days in a row���.

It is trivially true that if you are regularly seeing 25 SD events, then you have horribly (pdf) mis-specified your model. So why did Mr Viniar do it?

Incentives, that���s why. Goldmans wanted to take big positions in mortgage derivatives, and persuading themselves that they were safe was the way to do this. Banks need precise measures of risk to set trading limits, liquidity positions and gearing. You can���t run a bank by saying ���we don���t know��� even if this is true. And banks��� bosses don���t pay their underlings fortunes to say they don���t know. You need at least an illusion of knowledge. And because profits are privatized whilst losses are socialized, bankers have an incentive to believe that risk is smaller than it is. Mr Viniar might have seemed stupid when he said that. But he���s richer than you or me.

My next example of motivated stupidity comes from Geoff Mulgan���s pessimistic assessment of whether Dominic Cummings really can improve the efficiency of government.

Geoff says:

The average tenure of many Ministerial roles is barely a year now. Since it takes a year for even a smart minister to learn how to do the job, the result is that most ministers, most of the time, are incompetent.

But Prime Ministers have incentives to do regular reshuffles. They need to remind ministers who���s boss, and they maintain party discipline in part by offering backbenchers the prospect of office. If a PM promised to go five years without a reshuffle, he���d lose authority.

Geoff continues:

Without buy in from the bottom the top down changes rarely stick, even in states with authoritarian powers far beyond what UK ministers could dream of���If there is no strategy for engaging hearts and minds the programme is almost certain to fail.

But again, there���s an incentives problem. People in power don���t have an incentive to give underlings a voice, even if doing so would make an organization more efficient. This is why we see so much heavy-handed top-down corporate management even though we know that worker democracy is often more efficient.

And Geoff adds:

One of the big vices of Westminster and Whitehall is their valuing of words over deeds.

Again, there are strong incentives for this to be the case. It���s much easier (especially for Tories) to manage the media by briefings, soundbites and press releases than it is to put in the hard graft of actually changing things.

What I���m describing here are specific examples of a general fact. Good government is (by definition) a common good, whereas maintaining power and prestige is a private one. Politics is therefore always in danger of delivering a tragedy of the commons*.

What we have in both finance and politics is therefore incentivized stupidity - or at least the appearance of stupidity**. (And not just these occupations: journalism offers us other examples of this.)

A recent paper by Christine Exley and Judd Kessler give us experimental evidence for this. They show that when people had incentives to behave selfishly ��� for example in splitting cash between themselves and a charity ��� they often behaved apparently irrationally to give themselves more. They say:

Individuals make unambiguous decision errors ��� acting as if they suffer from cognitive limitations or behavioural biases ��� in order to make more selfish choices���Behaviour that could be attributed to a behavioural bias (such as anchoring���) might instead be indicative of self-serving motives.

I say all this as a corrective to a common error, particularly among Econ101ers. This is the belief that incentives are usually a good thing ��� that as Adam Smith said, ���it is not from the benevolence of the butcher, the brewer, or the baker that we expect our dinner, but from their regard to their own interest.���

Yes, incentives can be powerful. But sometimes make us act against the public interest. Getting incentives right is not easy.

* Of course, what Ostrom said of the tragedy of the commons is also true in politics: outright tragedies are often avoided thanks to unwritten rules and conventions. But these need shoring up. They cannot be taken for grant

** Whether such behaviour actually is stupid is questionable, given that it enhances the power and wealth of those engaging in it.

Chris Dillow's Blog

- Chris Dillow's profile

- 2 followers