Chris Dillow's Blog, page 24

January 21, 2020

Inequality under New Labour

Zarah Sultana���s recent claim that we have suffered 40 years of Thatcherism prompted Blairites to point to a big difference between Thatcher and New Labour ��� that whilst inequality rose a lot under Thatcher it largely levelled off under New Labour.

Measured by the Gini coefficient, this defence is correct. According to IFS data for incomes after housing costs, this coefficient rose from 0.261 to 0.374 from 1979 to 1996-97, but edged up only slightly more (to 0.405) during the New Labour years.

What should we make of this? A bit of me recalls Chris Rock: ���you want some credit for some shit you���re supposed to do.���

Also, though, the Gini coefficient is, essentially, an average of all inequalities. It can stay the same if inequality increases in some respects but falls in others. And this is what happened under New Labour.

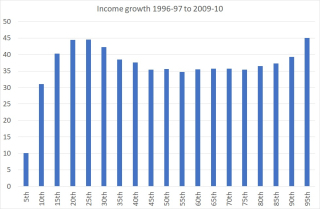

My chart, taken from IFS data, shows the growth in real incomes after housing costs, for each fifth percentile of the income distribution. It shows that it was the 20th-30th percentiles that did best under new Labour ��� that is, those worse off than three-quarters of people. These are those with incomes after tax and housing costs equivalent to around ��280 a week today for a childless couple.

Inequality tended to fall under New Labour because these got better off relative those on slightly higher than median incomes. This wasn���t just because of market forces. New Labour did genuinely help the moderately badly off with policies such as the minimum wage and tax credits.

Other inequalities, however, increased. One was between the very lowest incomes and this 30th percentile. Some of these shouldn���t be the object of our sympathy: they are wealthy folk who are living off their capital. Others, though, are those who have fallen through the safety net or are unemployed.

The other inequality that increased was at the top end. The 95th percentile ��� equivalent to a weekly income of ��1160 in today���s money ��� got even better off than the median. These IFS data don���t cover the very rich. But HMRC data do. And they show that the top 1% of taxpayers also did well under New Labour, with after tax incomes rising 56% compared to 38% for the median taxpayer. Peter Mandelson was famously ���intensely relaxed about people becoming filthy rich���. And they did just that.

The flattish Gini, therefore, disguises the fact that some inequalities fell whilst others rose.

Which poses two questions.

One is: how does the Tory government compare to New Labour?

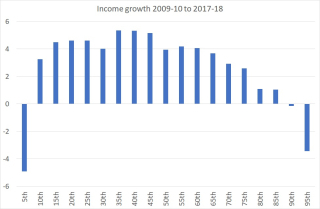

My second chart helps answer this. It shows a similar pattern in one regard: those slightly below median incomes have done well relative to both the very worst off and those on above-median incomes. But it also shows that the very best off have seen their incomes fall. Egalitarians should welcome the latter at least.

Perhaps the biggest difference with New Labour, though, is that the Tories have presided over little growth in incomes across the board. The group to have done best under the Tories are those around the 35th percentile (on ��340 a week in today���s money). Their incomes rose 5.3 per cent in real terms between 2009-10 and 2017-18. But this percentile saw income growth of 38 per cent under New Labour.

The second question is: which inequalities matter most? It is here, I suspect that New Labour was at fault.

The equality that it increased was that between those a bit below and those a bit above the median. This, though, is a second-order problem. People on moderately low incomes can live almost as well as those on moderately decent ones, at least with a bit of careful budgeting. Sure, they���ll have smaller houses and worse cars. But their spending on everyday items, and on nights out and even holidays, isn���t very much different.

Instead, what matters more are inequalities at both extremes. Very low incomes mean genuine distress; having to forego essentials; being only one accident away from catastrophe; the uncertainty about wondering how many hours you���ll get to work next week; and the cognition-sapping stress (pdf) of just getting through the week.

And at the other end, it is the increase in very high incomes (and the power that lies behind them) that has contributed to the slump in productivity growth. What���s more, such inequality undermines democracy as the ultra-rich leverage their wealth ��� and the undue deference they get ��� to acquire disproportionate political influence.

So, yes, Blairites are right: New Labour did greatly slow down the increase in equality we saw under Thatcher. But ��� in hindsight ��� it did not do enough to tackle the inequalities that most matter.

January 17, 2020

A case for nationalizing pensions

One of the fundamental questions in politics is: what should be done by the state, and what by the private sector? In at least one respect, I suspect that we have the mix wrong because there is a strong case for nationalizing pension provision ��� stronger, I suspect, than is the case for nationalizing utilities.

I say so because, as I point out in the day job, retirees and those approaching retirement face enormous uncertainties if they are managing their own pension: how long will I live? What will my spending needs be? And what will be investment returns? (Yes, equity returns have been great in recent decades, but we have no assurance whatsoever that the future will resemble the past.)

The state, however, is much better placed than the private sector to bear these risks. It can obviously pool longevity risk. And tax revenues are more stable than investment returns: in the financial crisis they fell only 3.4 per cent peak-to trough whereas MSCI���s world index in sterling terms fell eight times as much*. In particular, there is one source of risk to equity returns that the state can pool whereas retirees cannot ��� distribution risk, the danger of a shift in incomes from profits to wages. This would clobber (pdf) share prices, but not tax revenues.

And then, of course, there are deadweight costs. A private pension fund manager might easily charge a management fee of 0.5 per cent per year. On a ��100,000 pension pot invested over 20 years, that can add up to over ��20,000. State pensions are cheaper to administer. Fund managers are rich, civil servants are not, That���s a clue.

A common objection to a higher state pension is that it is unaffordable. This is nonsense in both fact and theory.

It���s nonsense in fact because spending on the UK state pension is projected to stay low. The OBR estimates that spending on pensions and other old-age benefits will rise from around six per cent of GDP now to 7.9 per cent in 2057-58. This would mean the state will spend less then than many European countries do today - among them Germany, which is not noted for fiscal profligacy.

It���s nonsense in theory too because, in a closed economy, all pensioners��� incomes must come from value-added created by current workers. The question is whether they pay pensioners via the tax system, or via the dividends and interest their employers pay**. For a given level of pensions, the burden is the same ��� only the name changes.

Granted, private pensions change this calculation by investing overseas and so extracting pensioners��� incomes from foreign workers. But the state can do this too. As Eric Lonergan has argued, we could set up a sovereign wealth fund which borrows at current gilt yields (almost minus 2% real) to buy higher yielding assets. Over time, this should give us all a big pension pot.

Even without that, however, we can achieve a sort of creeping nationalization over time by slightly strengthening the triple lock, one of George Osborne���s few laudable achievements in office. If we could look forward to a more generous state pension, we���d have less need to buy a private one so the latter would gradually wither.

We should regard the privatization of pensions as an example of how technocratic economic rationality can conflict with the logic of capitalism. Technocratic rationality says there���s a case for high state pensions. The logic of capitalism, however, requires that capitalist firms have sources of profits.

Another issue here is of course political risk: can we trust future governments to continue to raise pensions? Doing so requires there to be strong public demand for such a rise so that governments will fear a backlash if they do backslide. In this respect, the British can learn a lot from French protesters against pension cuts. We must regard a high and rising state pension not as a benefit but as an entitlement.

Which brings me to an under-appreciated point. The problem here is not merely one of economic privatization. A feature of modern British capitalism ��� neoliberalism if you like ��� has been a form of psychological privatization. What should be regarded as social problems have become individual ones. We see this with a lot of discussion of personal debt and mental health ��� an insufficient awareness of the social pressures which generate these. The same has happened with pensions. The question: ���how can we as a society provide a decent income for older people?��� has become: ���how can I provide for my pension?��� For too many ��� even the well-informed and affluent ��� this is too difficult a question.

* Of course, returns on more balanced portfolios were far more stable than equities ��� especially if they held decent quantities of non-sterling cash. But there are huge uncertainties about future risks and returns to balanced portfolios as well.

** OK, so taxes might deter investment, if they are badly designed. But so too do dividends and interest: high equity returns and bond yields mean a high cost of capital, by definition.

January 16, 2020

Great economics, bad politics

Non-economists (and quite a few trained economists too) often claim that mainstream economics is a simple-minded defence of free markets and inequality. Abhijit Banerjee and Esther Duflo���s Good Economics for Hard Times is a superb refutation of this.

They argue that:

It is unreasonable to expect markets to always deliver outcomes that are just, acceptable or even efficient.

A big reason for this is that the economy is ���sticky��� and that ���resources do not always flow to their best use. Workers who are laid off because of international trade or technical change do not quickly move to decent jobs: instead, job loss has permanent adverse effects on wages. Banks are slow to lend to good new ventures and to cut credit to failing firms. Efficient companies find it hard to displace less efficient incumbents. And so on.

In this respect, much of their book is a repudiation of rightists��� belief in a flexible market economy. Though they don���t say so explicitly, all this gives ample reason to doubt that firms will be able to seamlessly adapt to take advantage of post-Brexit trading opportunities (even assuming them to emerge.)

It���s not just the far-right they challenge. They question even conventional economists��� attachment to free trade. In the US, they write:

Those zones more affected (pdf) by the China shock experienced substantially larger reductions in manufacturing employment. More strikingly, there was no reallocation of labour to new kinds of jobs. The total number of jobs lost was often larger than merely the number of jobs lost in the industries that were hit (P81).

A similar thing, they say, was true in other countries (pdf).

Because of this, they show, the gains to an economy from international trade are small:

If the US were to go back to complete autarky, not trading with anybody, it would be poorer. But not that much poorer (p86)*.

They stress, however, that this is not to endorse Trump���s trade war. This, they say, causes a new set of economic disruptions which people struggle to adapt to.

Banerjee and Duflo also flatly reject rightist arguments against redistribution. High top tax rates, they say, ���are a perfectly sensible way to limit the explosion of top income inequality��� as there is no evidence they deter work effort or growth. And they add, ���there is no evidence��� that cash transfers to the poor make then work less.

Banerjee and Duflo never use the word neoliberalism. But in all these respects, Good Economics for Hard Times is a refutation of it. And as you would expect from them, it is magnificently evidence-based. All economists, I suspect, would learn a lot from it.

But but, but. Whilst the economics is wonderful, the politics is not. They write:

Bad economics underpinned the grand giveaways of to the rich and the squeezing of welfare programs, sold the idea that the state is impotent and corrupt and the poor are lazy, and paved the way to the current stalemate of exploding inequality and angry inertia. Blinkered economics told us trade is good for everyone. (p326)

Any they plead with us to ���set ideology aside���.

But Diane is right to reply to this that ���good economics is about more than technical expertise.���

Brexit give us one example of this. Economics clearly says this was a bad idea. But voters chose it anyway. This wasn���t only because the corrupt media prevented economists��� voices being sufficiently heard. It was also because voters had other priorities. Banerjee and Duflo rightly champion the economic benefits of immigration, but some voters looked instead at what they perceived to be the adverse cultural impact of it.

Worse still, Banerjee and Duflo over-rate the importance of ideas and under-rate the sheer power, material and ideological, of the rich. Martin Gilens and Benjamin I. Page (pdf) and Pablo Torija Jimenez show that western democracies favour their interests over those of the median voter. It requires much more than abundant economic evidence to fight this power. Banerjee and Duflo have given us lots of bullets to fire in the class war. But are they sufficient?

* Even I���m a bit queasy about this. I���m not sure it takes sufficient account of the fact that exposure to international trade raises productivity.

January 14, 2020

Two conservatisms

The death of Sir Roger Scruton reminds us of an overlooked fact, that there is a massive difference between the sort of conservatism he championed and free market economics.

Scruton defined conservatism as the ���instinct to hold on to what we love, to protect it from degradation and violence and to build our lives around it.��� The creative destruction of the free market economy, however, often endangers what we love. It is always threatening to destroy traditional communities and industries. Coal miners and steel workers in the 80s, protesting against pit and plant closures, were conservatives on Scruton���s definition but certainly not Thatcherites. And Patrick Minford���s vision of a post-Brexit economy in which manufacturing disappears is surely alien to the Scrutonian love of tradition.

Scruton himself was of course awake to this. The Times obituary quotes him as saying that ���Thatcher was completely indifferent to our kind of conservative philosophy.��� And at many points, he opposed modern-day capitalism: in his antipathy to big housebuilders with their ugly and shoddily-built boxes; in his defence of high culture against marketized ���pop��� music; in his claim that supermarkets are ���not only poisoning the world with packaging, they���re also destroying the ability of communities to survive without central distribution���; and in his critique of ���absentee capitalism.���

All of this, though, raises a question. Why is there not more hostility between Scrutonian and free market conservatives? Why is there not the vicious bitterness we see in the Labour party between Corbynites and their critics?

One reason, I suspect, is that disputes about thought are often less rancorous than those about power or personality. This is especially true for people who are wise enough, as many Tories are, to know that politics isn���t everything.

Also, Scrutonian and free market rightists have much in common. They share a scepticism of top-down state intervention and reverence for unplanned emergence ��� for what arises from the market in one case, and from tradition in another. Both believe, with some justification, there���s more unstated wisdom in emergent orders than there can be in conscious top-down direction.

Some of you might add a corollary to this, that both wings of Tory thought are united by a love of freedom. I���m not so sure. Whilst Scruton undoubtedly incurred cost and jeopardy in supporting dissidents in the old Soviet bloc, many Tories have been less enthusiastic about freedom and much more selective in whose liberty they have championed: that of Chileans and South Africans (and for many years women and gays in the UK) had a lower priority than east Europeans���.

But perhaps there���s something else. A while back, Bryan Caplan coined the phrase ���the libertarian penumbra��� to mean a set of beliefs which, whilst strictly not constitutive of libertarianism are in fact widely shared by libertarians. There is perhaps also a Tory penumbra, at least for those Tories who never bought into Cameronism. Things like a love of fox-hunting, a search for a genetic basis for inequality, hostility to climate change activists, hatred of the EU, or a perceived victimhood in the face of ���wokeness��� are perhaps not essential features of Toryism. But plenty of Tories share them ��� enough to create sufficient fellow-feeling as to compensate for what would otherwise be a large ideological gulf between conservatives and free-marketeers.

The flip-side of homophily, though, is exclusion. A love of ���home��� (a key element of Scruton's thinking) can easily spill into animosity towards immigrants; a defence of Christianity can tip into Islamophobia; and support of ���high��� culture can become a poncy snobbery.

Herein, I think, lies the reason why so many leftists hated him. Many ��� especially immigrants, ethnic minorities and even (despite Scruton���s own humble origins) those of us from working class backgrounds - sense that we don���t just belong among Scrutonian Tories. We fear that what also unites free market and Scrutonian Tories is, as Corey Robin said, a love of hierarchies ��� ones in which people like us are at the bottom.

Which raises a paradox. If we take Scruton���s definition at face value, almost all of us are conservative (just as almost all of us are working class on Marx���s definition!) The difference between us and Tories lies in what we love. People who value UK membership of the EU, or fear that VAR is ruining football are all Scrutonian conservatives. So too was the Communist Ewan MacColl when he tried to defend and revive English folk music in the face of commercial pressures for its decline. One of my favourite blogs, Jonathan Calder���s Liberal England, combines a reverence for English countryside and culture with Lib Dem politics. And one can argue ��� as Hilary Wainwright does ��� that Jeremy Corbyn is heir to an English tradition of radical dissent.

England has many traditions and customs, loved across the political spectrum. Tories who claim a monopoly on the love of tradition are adopting a very partial and reified notion of Englishness. Scruton himself saw this. In England: An Elegy (a book whose very title is anti-Thatcherite) he describes how his father blamed the Tories for the ���desecrated townscape of High Wycombe.��� Scruton pere was a conservative, not a Conservative. As are many of us. Which makes it all the sadder that Scruton himself was so sectarian and divisive a figure.

January 8, 2020

The strange death of libertarian England

It wasn���t just the Labour party that took a beating in last month���s general election. So too, but much less remarked, did right-libertarianism.

The Tories won on policies that repudiated many of their professed beliefs: a higher minimum wage; increased public spending; and the manpower planning that is a points-based immigration policy. And the manifesto (pdf) promise to ���ensure that there is a proper balance between the rights of individuals, our vital national security and effective government��� should also alarm libertarians. John Harris quotes an anonymous minister as saying that the libertarianism of Britannia Unchained is ���all off the agenda��� and that ���some of the things we���ve celebrated have led us astray.���

Tories are not out of step with public opinion here. If anything, it is even more antipathetic to right-libertarianism than are Tories. Most voters support higher income taxes on the rich, a wealth tax, and nationalizing the railways, for example. Rick was right months ago to say:

British voters don���t share the free-marketers��� vision���The important thing to understand about right-wing libertarianism is that it is a very eccentric viewpoint. It looks mainstream because it has a number of well-funded think-tanks pushing its agenda and its adherents are over-represented in politics and the media. The public, though, have never swallowed it.

A bit of me sympathizes with right-libertarians here. I suspect that one reason for public antipathy to free markets is that people under-appreciate the virtue of spontaneous order ��� that emergent processes can sometimes deliver better outcomes than state direction.

Nevertheless, all this raises a question: why are we not seeing more opposition to Johnsonian Toryism from right-libertarians?

You might think its because right-libertarianism has morphed into support for Brexit. Whilst I don���t wish to deny there is some link between the two, many Brexiter MPs have failed a basic test of libertarianism. In 2018 the likes of Bridgen, Cash, Duncan-Smith, Rees-Mogg and Francois all voted against legalizing cannabis.

One possibility is that they regard him as the lesser of two evils ��� they are supporting him with a heavy heart.

A second possibility has been described by Tyler Cowen. Intelligent right-libs have realized that free markets are not the panacea they thought and have shifted their priorities towards improving state capacity. Examples of this might ��� in different ways ��� be Dominic Cummings or Sam Bowman.

Perhaps relatedly, right-libertarianism has lost its material constituency. It once appealed to people by offering tax cuts. Today, however, many of the sort of businessmen who in the 80s wanted lower taxes now want other things, such as better infrastructure.

If these are respectable reasons for the decline of right-libertarianism, I suspect there are less reputable ones.

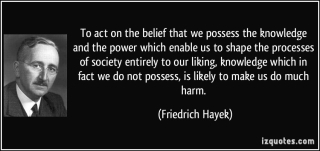

One is that we have lost the cast of mind which underpins right-libertarianism ��� that of an awareness of the limits of one���s knowledge. We need freedom, thought Hayek, because we cannot fully understand or predict society:

Since the value of freedom rests on the opportunities it provides for unforeseeable and unpredictable actions, we will rarely know what we lose through a particular restriction of freedom. Any such restriction, any coercion other than the enforcement of general rules, will aim at the achievement of some foreseeable particular result, but what is prevented by it will usually not be known....And so, when we decide each issue solely on what appear to be its individual merits, we always over-estimate the advantages of central direction. (Law Legislation and Liberty Vol I, p56-57.)

We live, however, in an age of narcissistic blowhards who are overconfident about everything. This is a climate which undervalues freedom.

Worse still, I suspect that some right-libertarians were never really sincere anyway. They professed a love of freedom only as a stick with which to beat the old Soviet Union. Liberty was only ever a poor second to shilling for the rich. And their antipathy to Gordon Brown was founded not upon a rightful distaste for the authoritarian streak in his thinking but upon simple tribalism. Maybe Corey Robin was right:

The priority of conservative political argument has been the maintenance of private regimes of power.

This isn't just a UK phenomenon, illustrated by Paul Staines: some (not all) US libertarians found it easy to throw in their lot with Trump.

Whatever the reason for the demise of right-libertarianism, however, there is perhaps another lesson to be taken from it ��� that you cannot nowadays achieve much political change via thinktanks alone.

January 4, 2020

Labour's public opinion dilemma

To what extent should Labour accommodate itself to public opinion, and to what extent should it try to change it? This fundamental question is posed, perhaps inadvertently, by Jess Phillips in an interview with the Times.

She says that people didn���t trust Labour to deliver the many promises in its manifesto:

People in working class communities know that you can���t always have everything. They know that this week you���ll put the money away for your holiday, next week you���ll put the money away for Christmas.

Now, I���m willing to accept that this is a fair description of many people���s attitudes to Labour���s borrowing plans. But it is, of course, a wholly wrong assessment of the economics.

For one thing, government borrowing is not like household borrowing. When the government borrows, it raises other people���s incomes and so increases its own tax revenues. And for another, governments can borrow on much better terms than working class households. Whereas they face interest rates of hundreds of percent, and have insecure incomes and so cannot be confident of being able to repay, government tax receipts are more stable and it can borrow for the long-term at a real rate of minus two per cent. This means that for every ��100 it borrows, it must repay only ��67 in today���s money over the next 20 years. Bond markets are paying the state to borrow. And if people are paying you well to do something, you should do it.

Voters can be forgiven for not knowing this, just as I hope I can be forgiven for not knowing the first things about dentistry or plumbing: civilization depends upon the division of labour. This is especially true because they have been ill-served by the media. One of the BBC���s many failings has been its near-total absence of any reporting of one of the most remarkable developments of recent years ��� that government borrowing costs have repeatedly hit record lows and stayed low.

All this leaves Labour with a dilemma. Should it base its manifesto upon reality, which is that increased borrowing makes sense? Or should it instead defer to public opinion and adopt a milder manifesto which appears ���credible���?

There is something to be said for the latter. You cannot change many people���s minds by snatched conversations on doorsteps during election campaigns. The job takes years, and requires resources (such as a benevolent mass media) which we do not possess. And in many cases, it���s a good idea to under-promise and over-deliver. Effective political parties should campaign in lies but govern in truth.

On the other hand, though, there are dangers here. One of Labour���s few advantages over the Tories is its mass membership. A centrist (and wrong) manifesto risks demotivating these supporters. And there���s the big risk that party leaders get high on their supply: if they prate about moderation and credibility long enough, they might come to believe such nonsense.

I���m not sure there is a correct answer to this dilemma. I would, however, hope that the next Labour leader at least appreciates that there is a difference between what���s true and what wins votes. I would also hope that he or she does not wrestle with it publicly.

January 3, 2020

Conservative arguments for radical ideas

In my previous post, I used a rhetorical device which I think leftists should copy. This is that we should use conventional, orthodox economics to reach radical conclusions.

The point here is that we don���t persuade people by telling them that their worldview is wrong and by demanding that they change the ideas of a lifetime. We are more likely to succeed by showing them that their ideas are consistent with things they might not have considered.

Here are some examples of what I mean.

- Fiscal policy. We don���t need MMT to argue for a significant fiscal loosening. Simple maths tells us that we can run big deficits and still see government debt fall as a share of GDP when real interest rates are negative, as they now are. And as Simon has said for years, the idea that we should use fiscal expansion when nominal interest rates are near zero is orthodox economics.

- The efficient market hypothesis. You don���t need heterodox economics to show that this is wrong. Instead, you can point out that the first test of the EMH���s corollary, the CAPM, found it to be false. That was conducted by those high priests of orthodoxy, Myron Scholes, Fischer Black and Michael Jensen. Their finding that defensive stocks do better than they should has been corroborated many times. And the other great challenge to the EMH ��� the out-performance of momentum (pdf) stocks ��� was first noted in that most conventional of publications, the Journal of Finance.

- Worker ownership. This sounds like a radical idea. But it���s not ��� and not just because law and accountancy practices are routinely owned by their workers. One inspiration for it comes from Hayek���s important point, that central planning is impossible because economic knowledge is fragmentary and dispersed. Worker control, more than hierarchy, can mobilize such knowledge. Hayek���s key insight ��� ���you don���t know what you are doing��� ��� is a challenge to top-down managers.

- Rents. The idea that landlords��� high rents are killing high streets and choking off economic growth might seem radical. But it���s not. It was one of the many brilliant insights of David Ricardo, the man revered by orthodox economists for discovering, among other things, the theory of comparative advantage.

- The falling rate of profit. This idea (which is true) is of course associated with Marx, because it predicts that capitalism will become increasingly stagnant and crisis-prone. But again, it���s not uniquely Marxian. The idea that diminishing returns would lead to a stationary state was, again, Ricardo���s.

What I���m suggesting here is, of course, nothing new: I pray each night that I will never have an original idea. All these are versions of an immanent critique ��� showing that existing conventional ideas aren���t necessarily as internally consistent as one might think, and might instead have radical implications.

This, I suspect was what Marx was doing when he argued that whilst the labour market looked like ���a very Eden of the innate rights of man��� things change when we go behind the factory door:

The can perceive a change in the physiognomy of our dramatis personae. He, who before was the money-owner, now strides in front as capitalist; the possessor of labour-power follows as his labourer. The one with an air of importance, smirking, intent on business; the other, timid and holding back, like one who is bringing his own hide to market and has nothing to expect but ��� a hiding.

Enlightenment ideas such as ���Freedom, Equality, Property and Bentham���, Marx showed, were not as compatible with capitalism as their advocates thought ��� something which remains true today.

Now, you might object that we need to do more than show merely that radical ideas are in fact quite compatible with conventional economics, and that we need to challenge it more. I agree: in particular, mainstream economics does a poor job of explaining inequality and exploitation.

However, if there is one thing we have learned in recent years, surely, it is that telling the truth does not always win arguments.

January 1, 2020

Wages vs social value

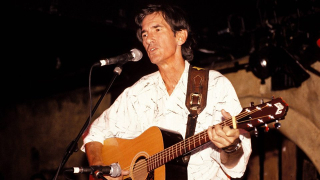

Today is the 23rd anniversary of the death of Townes Van Zandt, who is now universally regarded as one of the greatest songwriters ever.

And yet during his lifetime he made very little money. Even in his best years he got less than $100,000 from song-writing royalties, and for much of his life he might well have earned more from the oil drilling rights bequeathed by his rich family than from his music.

Which vindicates a recent tweet from Cameron Murray:

Actions that have social value only rarely coincide with actions that are monetarily compensated.

In Van Zandt���s case, this was partly because his genius was not fully recognised during his lifetime. But there are other reasons why Cameron point is correct in many more cases ��� reasons which are in fact entirely consistent with mainstream economics. I���m thinking of three ideas here.

1. Externalities. Let���s assume (heroically) that people are paid their marginal product. Even where this is the case, it is the private marginal product for which they are rewarded, not the social marginal product. The two differ because of externalities. A worker whose job generates huge carbon emissions or other pollution will have a wage greater than their social value.

There are other forms of pollution. There���s also risk pollution. In the run-up to the financial crisis, bankers were paid more than their social value because the risks generated by their activities would fall upon others; they were externalities. I suspect this is still the case.

And then there���s intellectual pollution. ���Writers��� such as Giles Coren or Toby Young have a highish marginal product for their employers, but their gibberings coarsen the public sphere. One baleful effect of Twitter is that this is brought to wider attention than previously and thus imposes a greater negative externality.

By the same token, there are also positive externalities, as when researchers��� findings inspire further ones. William Nordhaus has famously shown that innovators have captured ���only a miniscule fraction of the social returns from technological advances.���

2. Compensating advantages. Adam Smith thought the rewards to work tended to be equal across all occupations, once we considered both financial and non-financial returns. And, he said:

Honour makes a great part of the reward of all honourable professions. In point of pecuniary gain, all things considered, they are generally under-recompensed.

So, for example, professions such as nursing carry low wages but these are offset by a sense of pride and honour. But professions where these are lacking must pay more to offset that lack.

In his wonderful Bullshit Jobs, David Graeber has revived this idea. Many businesses, he writes, ���now feel that if there���s work that���s gratifying in any way at all, they really shouldn���t have to pay for it.��� But the same bosses who begrudge paying writers, he says, ���are willing to shell out handsome salaries for 'Vice Presidents for Creative Development' and the like, who do absolutely nothing.��� This is pure Smith: financial rewards offset the dissatisfaction that comes from doing a bullshit job, whilst enjoyable work pays less.

3. Bargaining. Your income does not depend upon how much social value you produce. It depends upon your power to extract that value. And Van Zandt was typical of musicians in being unable to do so. In Rockonomics, Alan Krueger wrote that ���musicians are not rewarded fairly for their services��� because they earn little compared to the countless hours of entertainment they deliver. He pointed out that the typical musician made only $100 in 2018 from streaming and that many artists have suffered from bad record deals: Paul McCartney, he says, made more money with Wings than he did with the Beatles. Jolie Holland, the Van Zandt of our era, has said:

I barely make a living. I think you have to be famous to make a living. I live out of a suitcase.

Although Econ101 tells fairy stories of how W=MP, bargaining (pdf) models are in fact mainstream economics: I recommend chapter 5 of Sam Bowles Microeconomics for a discussion of them.

Yes, we can and should supplement such models with analyses of how power relations (which of course include sexism and racism) also affect (pdf) wages and drive further wedges between social value and earnings. But we don���t need to do so to see that Cameron is right. Mainstream economics alone shows that wages need not often coincide with social value.

December 31, 2019

Yes, the BBC is biased

Over the weekend we saw two related examples of BBC bias. One came from Emily Maitlis, who said:

So often people read conspiracy into a thing when it���s really a confluence of cock-ups.

Sensible people, however, do not allege any conspiracy at the BBC. Instead, we have other concerns. Some are about incentive structures: which mistakes does it regard as mere cock-ups, and which as more serious offences? Another is that journalists, like all professionals, are prone to deformation professionelle ��� the fact that our training inculcates into us particular, and partial, ways of seeing things ��� which entails missing other things.

It is factors such as these that lead the BBC into error. Tom Mills, for example, says the corporation is too deferential to business and the state. It was perhaps this that, for example, led Laura Kuenssberg to repeat the government���s false allegation that a Labour activist had assaulted one of Matt Hancock���s aides. And Mark Oliver complains, rightly, that the Beeb wrongly prioritizes speed over context; misuses experts and thinktanks; and worries too much about reach and not enough about improving public understanding.

My second example of bias lies in Broadcasting House���s review of the decade (11���25��� in). It failed to mention what is the most important fact about the last ten years ��� the productivity stagnation*. And yet it was this that led both to Brexit and Corbynism, in part because flat-lining living standards provoked discontent with both elites and capitalism. I���ve said it before, and I���ll repeat it: the most important book for understanding the last ten years is Ben Friedman���s The Moral Consequences of Economic Growth.

I say these are both related examples of bias because they demonstrate something of which I���ve complained before ��� that the BBC has a bias against emergence. It does not see that many social phenomena are not simply the product of individual agency but instead arise independently of what people intend. Sometimes, these outcomes are benign, sometimes not: this issue was one of the differences between Smith and Marx **.

So, for example, Ms Maitlis doesn���t seem to realise that the BBC, like many organizations, can develop a logic of its own; they are not simply individuals writ large. Equally, the productivity slowdown is not the result of any individual���s action; it���s the unintended by-product of millions of dispersed decisions.

The BBC has consistently under-reported the latter because of another bias, shared by most journalists (what was that I said about deformation professionelle?) ��� a tendency to neglect slow-paced but important change. This is the same bias that has caused it to largely overlook the decline in global poverty in recent decades.

In saying this, I don���t pretend that the bias against emergence is confined to the BBC. It���s part of journalists��� training to look for agency ��� to ask, who���s to blame? Whodunnit? But the social sciences are not (often) an Agatha Christie story.

What we have here, therefore, is a troubling distance between the BBC and the social sciences; the latter are confined to niche programmes on Radio 4 whilst TV prefers the moronfests of Question Time and vox pops. Andrew Neil���s recent tweets claiming that ���the academic study of politics is increasingly irrelevant and in sad, serious decline��� and deprecating ���academic econometrics��� are symbolic of this distance.

But it matters. If journalists ignore the social sciences they will find it even harder to overcome the blindspots created by their own backgrounds and training: the sociological imagination can be a good corrective to journalists��� own distorted perspective.

That perspective, however, in turn distorts public debate. The fact is that the public are woefully misinformed about many things. Of course, this is not wholly the fault of the media: as Bobby Duffy points out in his excellent The Perils of Perception, people can go wrong without the help of journalists. But surely, the BBC ��� as the dominant source of news ��� must accept some of the blame for it. That it does not do so, at least in public, betokens an overconfidence which is the enemy of learning and improvement.

* To his credit, Niall Ferguson did allude to this.

** Both men were right: it depends on context.

December 17, 2019

A case for collective leadership

The debate about who should be the next Labour leader begs the question: should there be a single leader at all rather than a leadership team?

There���s much to be said for the latter*. For one thing, a good leader must do several jobs. They must develop policy; unite and inspire the PLP; win the votes of older Northerners without alienating metropolitan liberals; and motivate and recruit activists and organize an effective ground campaign. (The latter is important: Labour cannot win a top-down campaign and needs a strong mass membership to combat media lies.) There���s no reason to believe that the candidate best able to do one or two of these jobs an do them all. That���s a case for collective leadership.

Nor is there any reason to suppose that Labour members are well-equipped to choose a single best leader, and not just because they prioritize perceived ideological homophily over evidence of competence. Leftists have a long history - from Napoleon to Chavez and perhaps Corbyn ��� of investing leaders with qualities they do not in fact have and of regarding leadership as some magic quality. Collective leadership would put an end to these silly habits.

It would also help defuse the personal attacks which the next leader will face from the media. It will present (say) Keir Starmer as an out-of-touch privileged elitist but unleash a torrent of snobbery and sexism against (say) Rebecca Long-Bailey. But what if both were members of the leadership team? They could make one attack, but not the other. They���d be playing a futile game of whack-a-mole.

And there���s much to be said for collective leadership. As Jeffrey Nielsen showed in The Myth of Leadership, rank-based organizations demotivate subordinates and ignore the tacit knowledge of the many. In the same spirit, Archie Brown argues in The Myth of the Strong Leader that ���strength��� is much less of a virtue in leaders than things like energy, wisdom, adaptability and ability to handle diversity ��� virtues more likely to be found in a group than a single person. When a leader dominates his party, says Brown, he is often in fact kowtowing to some other group or person: Corbynites who attack Blair for following Bush and Murdoch, and Blairites who attack Corbyn for being in thrall to Milne would both agree with this. Collective leadership avoids that problem.

Better still, for me, is that it would help change the agenda. In choosing a leadership team rather than a individual, Labour would be making an important and true point ��� that large complex organizations cannot be run by a single person from the top down, and the belief that they can is a big cause of both inequality and inefficiency. They would raise a key question about all organizations: does this need to be run by Stalinist top-down methods and of so why? That���s the start of a direct assault upon inequality and centralized power.

For this reason, choosing a leadership team would be very different from the ���all must have prizes��� indecision that led to the Booker and Turner prizes being jointly awarded. A single prize is justified for an outstanding candidate. But leadership is not a prize. It is a means to an end. And sometimes, the end is best achieved by collective leadership.

Of course, such leadership requires that the joint leaders subordinate their egos to the collective good. But anybody unwilling or unable to do this is, by definition, unfit to hold a senior position in a socialist party.

The counter-argument to all this is that it doesn���t answer the question voters and the media will ask: who���ll be Prime Minister if Labour win the next election? One answer to this is that the UK does not have a presidential system, and shouldn���t. Prime Ministers used to be regarded as primus inter pares, and the question of who chairs Cabinet meetings should be only one that voters ask, and not be the most important. Politics is not an episode of Love Island, where you vote for your favourite character.

Yes, offering a leadership team will be presented by the media as "weak." But so too will any individual Labour leader, and leaders of the opposition often look weak simply by virtue of not being in power. Labour could reply to such silly allegations that there is strength in numbers, and the party has enough talent to provide several leaders, not one.

I say all this in the sure and certain expectation that Labour will do nothing like it. The party���s fixation with top-down (rent-seeking) leadership emulates the worst of capitalism. In this respect, it is not as radical as it should be.

* The Green party has, on and off, had co-leaders and principal speakers for years. I���m not sure whether their experience teaches us much, though. The challenge for a small party is how to raise its profile whereas the challenge for Labour is, in part, to avoid its leader being a liability.

Chris Dillow's Blog

- Chris Dillow's profile

- 2 followers