Chris Dillow's Blog, page 26

November 8, 2019

Resilience and selection

If truth is the first casualty of war, social science is the first casualty of election campaigns. So it was with Sajid Javid���s speech yesterday. He claimed that Labour will tax everybody more, ���saddle the next generation with debt���, ���ruin your finances��� and would be ���letting prices run wild in the shops.���

All this is silly hyperbole.

I say so not just because, as Simon says. Labour���s spending plans are more sustainable than the Tories because it will not inflict a damaging Brexit upon the economy.

Instead, there are two other reasons why Javid is wrong.

One is that developed economies are resilient. They just don���t tip swiftly from prosperity to ruin. For one thing, high debt (even if we get it) is no barrier (pdf) to decent economic growth. Also, as Eric Lonergan says, ���inflation is truly dead, and policy makers don���t need to worry about it.��� Governments and central banks have struggled to raise inflation despite trying. It would be odd if Mr McDonnell had powers unknown to the ECB or Bank of Japan. And we must remember the finding of John Landon-Lane and Peter Robertson, that government policies don���t usually change trend growth by very much ��� a result that is comforting as well as dispiriting.

Adam Smith was bang right. There is a great deal of ruin in a nation. Countries can cope with bad policies. Those on the right who say the UK (well, actually Britain) can survive leaving the EU therefore have a point. But you cannot easily claim that the economy is resilient to changes in trading rules but ultra-vulnerable to moderate differences in fiscal policy and taxes.

There is, however, another reason why economies aren���t ruined by bad policy. It���s that such policies don���t persist. They get reversed. Examples of this include Mitterrand���s ���austerity turn��� in 1983 and Syriza's acceptance of EU-imposed austerity in 2015. But we have also seen examples under the Tories. Thatcher abandoned M3 targets and fiscal austerity in the mid-80s: cyclically adjusted net borrowing rose from a small surplus in 1981-82 to 2.8% of GDP in 1983-84. And Major pulled the UK out of the ERM in 1992.

Liberal democratic capitalism, then, selects against bad policies. Ones which damage the economy egregiously get reversed. If Labour���s policies are as bad as Javid claims (arguendo!) the correct inference is not that Labour will ruin the nation, but that Mr McDonnell will disappoint his supporters as so many of his predecessors have done.

Herein, I think, lies an under-appreciated reason for voting Labour. Selection pressures against bad policy apply more strongly to Labour than to the Tories, not least because policies that hurt capital arouse more powerful hostility than ones that only hurt the poor. Mediocre Labour policies will meet stiff resistance from the media and capital, whereas the Tories can get away with worse. The ���hostile environment policy ruined many lives. And Austerity killed over 100,000 people and is only now being reversed (and for other reasons). It���s difficult to imagine that Labour policies that did so much harm could persist for so long.

Risk-averse people who are uncertain about the social and economic impact of the party���s policies should for this reason favour Labour: the worst they can do is very likely ultimately better than the worst the Tories can do.

November 6, 2019

Shoring up capitalism

They are not talking about it explicitly, but one of the interesting divisions on the centre and right in this election concerns the question: how best to sustain British capitalism?

Here, there are two related issues.

The first is: are we in a wage-led or profit-led regime? Sometimes (pdf), profit rates can be raised by policies and institutions that promote (pdf) full employment and high wages, as these boost aggregate demand. At other times, though, restoring profits requires policies to depress wages and rebuild profit margins. Tory governments in the 50s and 60s pursued wage-led policies, but Thatcher pursued profit-led ones.

Whether wage- or profit-led policies work varies from time to time and place to place, as Marglin and Bhaduri (pdf) and Onaran and Galanis (pdf) have shown.

The second issue is that there is sometimes a distinction between legitimacy and accumulation. This was put by James O���Connor back in 1973:

The capitalistic state must try to fulfill two basic and often contradictory functions ��� accumulation and legitimation. This means that the state must try to maintain or create the conditions in which profitable capital accumulation is possible. However the state also must try to maintain or create the conditions for social harmony. A capitalist state that openly uses its coercive forces to help one class accumulate capital at the expense of other classes loses its legitimacy���But a state that ignores the necessity of assisting the process of capital accumulation risks drying up the source of its own power. (The Fiscal Crisis of the State, p6)

Brexit, I think, embodies this conflict between legitimation and accumulation. On the one hand, it���s bad for accumulation as it���ll reduce economic activity to some degree. But on the other, you can see it as an attempt to shore up legitimacy by showing that ���the elite��� can give the people what they want.

Which poses the question: what are the centre and right parties offering in these dimensions?

In wanting to stop Brexit, the Lib Dems are going for accumulation at the expense of legitimacy. Which isn���t to say they are ignoring the latter completely. Jo Swinson claims that:

Politics is no longer about left or right. It's about open or closed. Liberal or authoritarian.

This is a longstanding theme of centrists ��� an effort to pretend that we are divided by something other than class. In being mostly on the liberal-open side of this divide, capitalists are on the same side as many workers. Insofar as playing up this distinction works, it thus serves to enhance capitalist legitimacy by effacing the capital-labour divide.

In pursuing Brexit, however, the Tories are going for legitimacy at the expense of accumulation. Their attitude to the latter, though, seems ambivalent. On the one hand, promises to raise the minimum wage and public spending suggest a wage-led mindset. But on the other, the prominence in government of Britannia Unchainders such as Patel, Raab and Truss suggest a profit-led tendency ��� a possibility consistent with the fact that Johnson���s Brexit deal opens the door for cuts in UK labour protections. This division might well reflect a division among capitalists themselves, with what Phil calls ��� the most backward, uncompetitive and socially regressive sections of capital��� having disproportionate influence.

Another interesting case is the Brexit party. Pursuing the hardest possible Brexit is obviously a threat to accumulation. But I���m not sure either that they are trying to shore up legitimacy. Quite the opposite. In fuelling permanent resentment against the elite they are undermining it: there might in this sense be no great incongruity in Claire Fox���s migration from the RCP to Brexit party. Granted, the resentment is directed at political rather than economic elites. But this is a distinction that might be hard to sustain; the problem with rocking the boat is that there���s no telling who���ll fall out.

None of these answers to the question of how to sustain capitalism seems wholly satisfactory ��� which isn���t entirely surprising given that none of the parties has the wit to ask the question explicitly. Which is why a few intelligent capitalists, such as Dan Davies, are attracted to Labour.

But why aren���t they offering good answers? It might be that they���re just not smart enough. Sam Bowman and Stian Westlake have suggested ways in which the centre-right might bolster accumulation, but their ideas haven���t yet been embraced. But it might instead be that it���s not at all obvious what would shore up capitalism: wage-led policies might work, but then again might not. If so, the parties��� confusion reflects the messiness of the real world.

November 1, 2019

The right's mega-rich problem

���I don't think anyone in this country should be a billionaire��� said Labour���s Lloyd Russell-Moyle yesterday, at which the BBC���s Emma Barnett took umbrage. The exchange is curious, because from one perspective it should be conservative supporters of a free market who don���t want there to be billionaires.

I say so because in a healthy market economy there should be almost no extremely wealthy people simply because profits should be bid away by competition. In the textbook case of perfect competition there are no super-normal profits, and in the more realistic case of Schumpeterian creative destruction, high profits should be competed away quickly.

From this perspective, every billionaire is a market failure ��� a sign that competition has failed. The Duke of Westminster is rich because there���s a monopoly of prime land in central London. Would Ineos��� Jim Ratcliffe be so rich if pollution were properly priced, or if his firm faced more competition? How can hedge funds get away for so long with their ���2 and 20��� pricing? (Hint: it���s for the same reason that Friedman thought government spending was inefficient, because people are spending other people���s money.) And so on.

What���s more, monopoly pricing is a form of tax ��� a tax which often falls upon other, smaller businesses, as Frederick Guy argues (pdf):

Monopolies, by their nature, set prices and extract rents from their customers. Current technology monopolies are collecting taxes based on the global distribution of their products like ancient empires exacting tribute from distant provinces and returning them to spatially concentrated bases. Microsoft produces its Windows and Office products in the Seattle area, and harvests license fees globally, as does Monsanto (Bayer) for the seed varieties and complementary herbicides engineered in St Louis. Booking intermediaries like Airbnb, Trip Advisor, Booking.com, Expedia (Microsoft, again), and Uber take significant slices of revenue from many thousands of globally dispersed small businesses.

In this sense, not only are billionaires a symptom of an absence of a healthy competitive economy, but they are also a cause of it: their taxes on other firms restrict growth and entrepreneurship. What Brink Lindsey and Steven Teles say of the US economy is probably true of the UK too:

The US economy has become less open to competition and more clogged by insider-protecting deals than it was just a few decades ago. These deals make our economy less dynamic and innovative. (The Captured Economy, p5)

In a similar spirit but different perspective, Michael Kremer, Christopher Snyder, Albert Chen show that the costs of monopoly are greater than conventional economics suggests.

Tories are wrong, therefore, to portray attacks on the mega-rich as the politics of envy. It���s not. The existence of billionaires is a sign and cause of a dysfunctional economy. Equally, though, this is not solely a tax issue.The way to stop people becoming billionaires is to have much stronger competition policy and less restrictive intellectual property laws as well as support for new entrepreneurs who want to compete against incumbents: entrepreneurial Marxism is a thing. Taxes upon the mega-rich should be seen as a backstop, a way of compensating for past market failures.

In fact, logically, it is rightists who should be most concerned by the concentration of wealth. We lefties can point to it as evidence that the system is rigged. But Tories should worry that it undermines the legitimacy of the existing order not only because people don���t like inequality, but because it slows down economic growth and so encourages demands for change.

Those of us formed in the 80s see another paradox here. Back then, Tories championed the ���free market.��� Great wealth, though, is a sign that the free market isn���t working well, that there isn���t enough competition, which should trouble free marketeers.

All of which poses the question. Why, then, are rightists like Ms Barnett and Douglas Carswell standing up for the mega-rich when it is they who should be most discomfited by their existence?

Adam Smith had one theory:

The great mob of mankind are the admirers and worshippers, and, what may seem more extraordinary, most frequently the disinterested admirers and worshippers, of wealth and greatness.

There is, though, another possibility. Maybe all that cheering for a dynamic free market economy was simply insincere. Tories might like the forces of competition when they throw miners and steel-workers out of jobs, but are not so keen on them if they threaten the very rich. Maybe the right doesn���t really believe in things like free markets or liberty after all. Instead, their one principle is the support of inequality. As Corey Robin has written: ���the priority of conservative political argument has been the maintenance of private regimes of power.���

October 31, 2019

Trust cycles in politics

Opinion polls, for what they are worth, show that support for the Lib Dems has risen. This seems part of a cycle. Support for the party rose from the 70s to mid-80s, then declined to the late 90s, then rose again until 2010 before slumping in 2015 but has risen since.

Coincidentally, something else is also cyclical ��� trust. You all know somebody who has been repeatedly let down by their partner. You might even be that person. The cycle is familiar. After a betrayal you say you���ll never trust her again. But then the memory fades and wishful thinking and horniness take over so you get back with her until she lets you down again. And so the cycle starts again. As Frank sang:

Time and time again I went away

But then would come the time when I would need you

And once again these words I'll have to say

I'm a fool to want you

Minsky cycles (pdf) in financial markets work the same way. In good times, investors gradually build up trust that risky assets will pay off well: Nicola Gennaioli and Andrei Shleifer���s A Crisis of Beliefs is a nice description of how this happened in the 00s. This causes increased speculation which leads to a crash. After the crash, everyone is burned and distrustful. But eventually, as with lovers, memories fade and wishful thinking returns and so the cycle begins again.

Fraudsters exploit this cyclicality. When trust is low, they need to build it. They have several ways of doing so, some of them described in Dan Davies��� brilliant Lying for Money.

One thing they do is act honestly for a while. In long firm frauds con men run an apparently legitimate business and build up trust so they can get longer credit lines. And when they���ve borrowed a lot they suddenly run off with the money.

Such apparent honesty supports something else - the need to wait for memories to fade, or for new marks to arrive who have no memory or knowledge of betrayal. It���s now nine years since the Lib Dems voted to triple tuition fees.

They also exploit desperation. The sick person desperate for a cure is easy prey for quacks. The woman desperate for a man will find a wrong ���un. Investors disappointed with returns on conventional pensions might well cash them in and turn to scammers instead. And the voter disillusioned with the two main parties���

Yet another trick is product differentiation. Werner Troesken showed in a magnificent paper (pdf) that snake oil sellers thrived for decades because each took great effort to distinguish himself from his rivals. Millions of women have been cheated on by men who ���aren���t like the others.��� And Lib Dems��� popularity has for years risen or fallen according to whether they can successfully distinguish themselves from the ���discredited two main parties.���

And then there���s affinity fraud. We trust people who seem like ourselves. Con men know this: Bernie Madoff���s victims were fellow Jewish county club members. The man who claims to have been cheated on can lure the vulnerable woman. Similarly, Lib Dems will win votes from Labour if they can successfully claim affinity with Remainers, but will lose them if Labour can instead associate them with austerity.

Of course, some of you might claim that the Lib Dems are not in fact con artists. Maybe not, But it���s surprising how many parallels there are.

October 30, 2019

Mechanisms, not numbers

The NIESR claims that Johnson���s Brexit deal ���would ultimately lead the UK economy to be about 3.5% smaller than it would have been had the UK remained in the EU.��� Reaction to this, I fear, highlights an important way in which the media and public misunderstand economics. They pay too much attention to numbers (and seek a spurious precision in them) and too little to mechanisms.

To see what I mean, consider the NIESR���s reasoning. This starts from the fact that leaving the EU���s single market will throw a little sand into the wheels of trade by imposing trade barriers ��� ���not the classic barriers of tariffs, but the insidious ones of differing national standards, various restrictions on the provision of services, exclusion of foreign firms from public contracts.��� (I���m quoting Lady Thatcher, who called the single market ���a fantastic prospect for our industry and commerce.���) A few days ago, Dominic Raab and Priti Patel claimed that Johnson���s deal was great for Northern Ireland because it gave the region ���frictionless trade��� with the EU. But if frictionless trade is good for them, its absence must be bad for us.

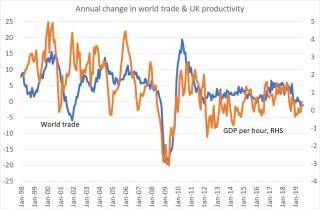

Now, you might object that these barriers will be small ��� and they will initially given that we start from the same regulations and product standards. But this is where another mechanism becomes absolutely crucial. My chart hints at what this is. It plots annual growth in world trade (as measured by the CPB) against UK GDP per worker-hour: the data starts in 1997 as this is when monthly GDP data begins. It���s obvious that there���s a strong correlation between the two.

Of course, a big reason for this is that the same things drive both, such as fluctuations in credit conditions, animal spirits and aggregate demand. But this is not the whole story. We���ve strong reasons to think that world trade drives productivity. One reason for this was pointed out in the first lines of the first book on modern economics. ���The greatest improvement in the productive powers of labour��� wrote Adam Smith ���seem to have been the effects of the division of labour.��� Greater world trade means greater division of labour and hence more efficiency. Also, freer trade encourages exporting firms to expand, which raises productivity as workers shift to these better firms. And then there���s the fact that more trade increases competition which spurs firms to raise efficiency and innovate. There���s also a knowledge diffusion channel; if managers visit suppliers and customers overseas, they should learn from them ways of increasing efficiency. As Danny Blanchflower says, you can learn a lot just by walking around.

These mechanisms are crucial. Over the long-run, they act as a multiplier. They cause apparently small barriers to trade to lead to significant losses of income because less trade means less productivity.

But we don���t know precisely how powerful these mechanisms are. Yes, fact and theory tell us their direction: the natural experiment of dividing Korea proves that openness creates prosperity. But their magnitude is uncertain; this is why the NIESR's estimate differs from that of the UK in a Changing Europe (pdf).

In fact, there���s another uncertainty. We don���t know what future trading arrangements will be. Brexiters claim the frictions in trading with the EU will be minimized by a deep free trade agreement, and compensated for by freer trade elsewhere. Many, though, are sceptical of this: as the old saying goes, a bird in the hand is worth two in the bush. Even 10% rises in goods exports to China or Japan would not compensate for a mere 1% loss of exports to the EU ��� and 10% is perhaps an optimistic estimate of what free trade deals typically achieve.

For these reasons, Julian Jessop is right to say there are big uncertainties around the NIESR���s estimate. This does NOT, however, justify philistine sniping at economists: ���what do they know, ner, ner?��� Instead, it directs our attention to the main issues: how strong is the link between trade and productivity? How likely are we to get meaningful trade deals? And what would these do to actually boost trade? It is possible to have a rational, intelligent debate about these issues ��� not that we���ll get one on the BBC.

Julian says these uncertainties cause him to ���give little weight to long-term forecasts.��� Some of us, however, draw the opposite inference: what is the point of introducing such uncertainties into the economy when there was no pressing need to do so?

October 29, 2019

On constraints in politics

When I tell people that I work from home, they ask me how I have the discipline to do so. The answer is that I don���t. I just have a habit: I start work every weekday after breakfast without fail, so I can often get a few hours done before I���ve started thinking. If I were to wake up every morning and ask ���what do I feel like doing today?��� I���d never do any work.

I use a similar rule in my investments. Mostly, I make a direct debit into a tracker fund each month and an Isa contribution every November. If I had to do otherwise, I���d not save enough or make all sorts of silly stock picks. And I do the same for exercising: I go to the gym four times each week at about the same time so I���m on the crosstrainer before I���ve had a chance to ask whether I feel like it or not.

Strict habits do for me what tying himself to the mast did for Ulysses when he feared the Sirens would lure him onto the rocks. They save me from my own mistakes. All of us are potentially irrational in countless ways, in the sense of acting against our own interests. Like Ulysses, we need constraints to prevent us acting on this irrationality.

Which raises a problem. In politics, these constraints aren���t strong enough. As Paul Evans says, the EU plebiscite helped weaken our traditional system of representative democracy which was ���almost specifically designed to stop leaps into the unknown.���

63% of voters think MPs should do as their constituents wish, even if this goes against their own judgement: they don���t think MPs should act as constraints upon the hasty opinion of the mob. Not that MPs are well able to do so anyway: parliamentary candidates are selected by a handful of cranky fanatics often on the basis not of ability of ideological conformity. You all like to point and laugh at the likes of Bridgen, Francois or Burgon. But what you should be doing is ask: if they���re so stupid, how did they become MPs?

And then, of course, there is the media. This does not reveal truth and expose lies but instead operates as a broadcaster of those lies.

None of this is to claim there was ever a Golden Age of wise legislators exercising Solomonic judgment. There wasn���t. But it does mean we have a problem. We know that we all have limited rationality and knowledge. If we are to tackle socio-economic problems we must try to overcome these limits by restraining ignorance and irrationality. And yet our political system does not do so. Worse still, many politicians and commentators treat politics as just another marketing exercise and don���t even see a problem. They don't even see the question asked by Daniel Hausman: why should we satisfy preferences that are irrational or mean-spirited?

But there is. And this should not be a partisan matter. Those Brexiters who are so keen on invoking the ���will of the people��� should ask: would I be so enthusiastic about this will if a leftist government were to appeal to it to justify widespread nationalization?

Of course, traditionally, there have been many Ulyssesian constraints, some of which still exist. One of course is the law, which is sometimes regarded as a substitute for politics. Technocrats have devolved some decisions to experts, such as in giving the Bank of England operational independence. Rightists have traditionally favoured limited government so that political irrationality can do only little damage ��� although this option has fallen out of favour recently, not necessarily for good reasons. And yet others ��� such as Jason Brennan ��� advocate limiting the franchise to knowledgeable electors.

But there are other methods. What we need is the promotion of what Habermas called communicative rationality ��� methods of debate which rest upon truth and rationality and in which everybody has an equal say. Such methods mean that irrationality is constrained whilst cognitive diversity is encouraged. In his book Save Democracy, Abolish Voting Paul advocates mechanisms for doing this. We also require institutions (pdf) of deliberative democracy, whereby citizens can weigh evidence properly rather than act upon irrational whims.

One thing we���ll learn from the upcoming election campaign ��� and, I fear, perhaps the only thing ��� is that our existing institutions are a million miles away from such an ideal. And worse still, very few people care.

October 25, 2019

Narrative Economics: a review

For years, thinking about economics has been heavily influenced by the idea of homo economicus ��� that people are rational and well-informed. Robert Shiller���s latest book, Narrative Economics, is an attempt to replace this conception with that of people as homo narrans (pdf) ��� story-telling animals. He writes:

Ultimately, the mass of people whose consumption and investment decisions cause economic fluctuations are not very well informed. Most of them do not view or read the news carefully, [and they���d be little better informed if they did ��� CD] and they rarely get the facts in any discernable order. And yet their decisions drive aggregate economic activity. It must be the case, then, that attention-getting narratives drive these decisions.

Much of the book (which is an extension of an earlier paper (pdf)) is an enjoyable and well-informed description of such narratives. I especially liked his discussion of bimetallism, wherein he shows that Brexit is not the first debate about an abstruse issue which triggered a culture war ��� although bimetallism has the advantage of bequeathing us the Wizard of Oz.

There���s one Big Fact which is consistent with the idea that narratives drive economic activity. It is that asset prices are prone to momentum. This is especially the case in the housing market. Since Nationwide monthly data began in 1991, there has been a significant correlation (of 0.45) between annual inflation in one period and in the next. And Meb Faber has shown that a simple rule of buying equities when prices are above their ten-month moving average and selling when they are below it has beaten a buy-and-hold strategy ��� something which applies to UK and emerging market stocks as well as the S&P 500.

One reason why momentum exists could be that prices are driven by narratives and that these spread like epidemics ��� a point previously made (pdf) by Christopher Carroll. A story that���s driven prices up in one period can infect other investors and so drive prices up in the following period.

Perhaps, then, homo economicus is itself an example of narrative economics, a story that has gained hold - ��� as Katrine Marcal has argued.

For me, this raises three issues.

One is: what causes some narratives to go viral whilst other don���t? It is not merely their truth-value: the Laffer curve and the Great Moderation were both popular stories too. Shiller says there���s a big random element to whether a story will take hold:

Just as it is difficult or impossible to predict which motion picture will be a box office hit, it is difficult to predict which narrative will eventually have economic impact.

Again, a Big Fact is consistent with this. It is that economists have consistently failed to forecast recessions ��� which might be because they���ve under-rated the role and spread of narratives.

A second issue is: how consistent is all this with homo economicus?

On the one hand, it might merely add substance to max U stories: it is narratives that form our tastes (not least for risk) and shape expected returns; think of the stories that drove up tech stocks in the late 90s.

On the other hand, though, stories are dangerous. They encourage us to see patterns and to overlook randomness. We thus get an illusion of knowledge and hence overconfidence. And so we take on more risk and buy more speculative stocks than a rational investor might. In this way, homo narrans is at war with homo economicus.

My third issue is: if narratives matter to people in their economic lives, when their own money is at stake, might they be even more influential in areas where individuals have less skin in the game? Perhaps narratives matter more in politics than in economics. Which, given that their popularity is not a function solely of their truthfulness, might be a problem.

October 24, 2019

Politics as natural selection

I wrote the other day that the division over Brexit suits our rulers just fine, because it helps to distract from the class division. This sounds like a conspiracy theory. But it���s not. It reminds us that we should think of politics as being a bit like natural selection; mutations/policies emerge randomly and the environment selects among them so that only mutations/policies that are suited to the environment persist.

Take, for example, Thatcher���s privatization programme which has been called ���her most important and enduring economic legacy.��� This, however, was not originally intended to be so transformative. As the Institute for Government says (pdf), the first of Thatcher���s privatizations ��� of some shares in BP and of British Aerospace and Cable and Wireless - ���were treated as discrete sales whose aim was to raise revenue for the Exchequer.��� And Jon Stern says (pdf) the first big privatization, of BT in 1984, ���was largely driven by the need to get BT���s investment programme off the Public Sector Borrowing Requirement.���

We can think of privatization, then, as being like a random mutation. It was a policy adopted for one reason that became successful and long-lasting for other reasons. The environment selected for a randomish mutation.

Thatcherism provides other examples. Her using the 1981 recession to smash trades union power was accidental; the recession was unintended and unpredicted. But it worked. And Big Bang was not intended to kickstart the financialization described by Grace Blakeley; it was seen at the time as an attack on another restrictive practice. Again, it was a mutation that thrived.

This isn���t to say that Thatcher���s mutations all succeeded; the poll tax was one that was killed off.

Nor is it to say that even successful mutations survive forever. A nice example here is the wage-led economic regime (pdf) of the post-war era. In the 50s and 60s rising wages and the promise of high demand encouraged firms to invest more and so the economy grew well. For many years wage-led growth was a successful mutation. But in the 70s, this ceased to be the case: a squeeze on profit margins deterred investment and reduced growth. The environment then selected against wage-led growth and ��� in the US and UK at least ��� in favour of profit-led growth, whereby a reassertion of capitalist power restored growth. Today, however, this mutation is in doubt; perhaps wage-led growth would now work better (pdf).

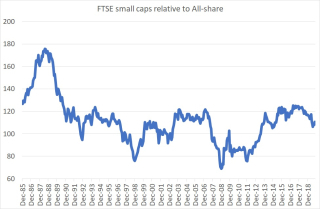

If so, what we have here is a process a little like the population cycle in biology: a successful species can eventually deplete its environment and so die back. Andrew Lo has shown how such a thing happens in financial markets: as investors pile into successful strategies, these grow too big (causing the mispricing to disappear) and their profitability wanes. But then, when the strategy/species is small enough relative to its food source/profits, it begins to grow again. The performance of small stocks fits this pattern. They did well in the 80s as investors realized they had been under-priced. But as the ���buy small caps��� strategy expanded it depleted its food source with the result that small caps under-performed in the 90s. By the late 90s, though, they had fallen so far out of favour that the strategy could again pay off ��� until 2007 when they became over-priced again.

Politics might be similar. The environment can select for a policy in one period, against it the next, and for it later.

But what is the environment that���s doing the selecting? It is not economists��� idea of optimal policy. Instead, it is admixture of capitalism and the media-political system (two things which of course are not separate). A big aspect of this is that policies that seriously endanger profits and growth get selected against - eventually.

The selection need not, however, be fierce. Just as some mildly maladapted species can survive, so might policies: there is, as Adam Smith said, a great deal of ruin in a nation. Austerity might be an example of this.

One complication here is that profitability isn���t the only thing that determines whether a policy is adapted or not. What also matters is legitimacy. Policies and institutions can persist if they jeopardize profits if they help to sustain the legitimacy of the system.

Perhaps Brexit fits this. No Tory ever thought "let's divide the country into Leave and Remain so that people are distracted from class politics." The Leave-Remain divide is a random mutation (from the point of view of capitalism) that has been selected for - so far.

The Tories��� populist turn can be seen as trading off some accumulation in order to achieve greater legitimacy, in the sense of more hostility to the left. One reason why many capitalists are sceptical of this, however, is that they aren���t sure the trade-off worth making.

Is it? I don���t know. Just as natural selection is a random and unpredictable process, so too perhaps is policy selection ��� which is why so much political forecasting, long-term and short, has failed. The question: "what is the right policy?" doesn���t necessarily yield the same answer as: "what policy gets selected?"

Now, I concede this framework is vague ��� hey, it���s only a blog post, a first draft. But I think it has at least one virtue. It enables us to speak of policies as favouring capitalism without having to invoke conspiracy theories or the idea that we are ruled by evil geniuses.

October 22, 2019

Detoxifying Brexit

The Brexit debate has become ever-more fraught, and whatever happens next it is likely to remain so. Which poses the question: what can we as individuals do to dial down the hysteria and civilize the debate? Here are some suggestions.

Draw the right inference from the media.

Whenever I hear a Brexiter on the BBC, I���m inclined to believe more strongly in the case for Remain. Be it Mark Francois thinking he���s re-enacting the Battle of Britain, or the cynical bad faith or Raab and Patel���s claim that Johnson���s deal is great for Northern Ireland because it gives it ���frictionless trade��� with the EU, their arguments are often counter-advocacy.

But we should not infer from this that all arguments for Brexit are nonsense. Instead, they tell us more about the media and politics than about Brexit. They tell us that selection mechanisms are broken ��� that MPs are selected for fanaticism not competence and that the BBC wants ���good TV��� and ���senior sources��� rather than to enlighten its audience.

Construct a counter-argument for yourself.

If you support Brexit, ask: what is the strongest case for remaining? And if you don���t, ask: what is the best argument for leaving? For me, the strongest argument is not so much that the EU is a barrier to trade with the rest of the world ��� high tariffs (pdf) might instead be a sign of the difficulties of striking free trade deals ��� but that it suffers a democratic deficit and, in its treatment of Greece and tolerance of fiscal austerity, is insufficiently pro-growth.

Also, we should ask: what are the weaknesses of our side? Those who favour remaining should ask why their campaign failed in 2016, especially with the ���left behind.��� And those who support leaving should ask why all reputable economists think that doing so will make us poorer.

Ask: why would intelligent people support the other side?

The 52% who voted Leave are not all fools, any more than are the 48% who voted Remain. As Simon Kuper says in a different context, ���treat every situation as a learning opportunity.���

Forget conspiracy theories.

Leave supporters are not disaster capitalists. And Remain supporters don���t support EU membership because the EU pays them.

Ask: what type of democracy do we want, and how can we sustain it?

Of course, Brexit is no longer just (or even mainly) about the EU. Some who support Leave, I suspect care more about respecting the ���will of the people��� than about the details of Brexit. The conflict, therefore, is about whether we want direct or parliamentary democracy.

Both sides should scrutinize their own position here. Leave supporters should remember that the ���will of the people��� will not always be on their side. Would Jacob Rees-Mogg or Iain Duncan Smith be so keen on the will of the people if it were used - as polls suggest it could be - to justify widespread nationalization? They should therefore ask what sort of filters should be applied to the will of the people. And remain supporters should ask: why has parliamentary democracy become so unpopular, and what can be done to reverse this?

Avoid cognitive biases.

It���s easy to see cognitive biases in the other side. I suspect that Brexit supporters are prone to a form of halo effect and wishful thinking in believing that Brexit will be good for the economy.

It���s harder, though, to see them in ourselves But this is all the more reason to try. I fear I am prone to groupthink and deformation professionnelle (the tendency for ones��� professional training to distort one���s perspective: I tend to agree with the mass of economists who oppose Brexit, and I perhaps overweight economic considerations and underweight ones about identity. I might also be guilty of asymmetric Bayesianism: I���m so revolted by Farage and Francois that perhaps I become more militantly pro-Remain than the evidence might warrant.

Dial down the fanaticism

Millions of people are wrong about millions of things all the time. Being wrong is the human condition and is forgivable. What matters is that our errors be corrigible. And this requires that we not be fanatics, that we stand back from our beliefs ��� that we adopt what Richard Rorty called liberal irony.

You might object that a 6%+ hit (pdf) to GDP is something to be worked up about. Up to a point. The distributional impact of this (to an extent) is a matter of political choice ��� a choice separable from Brexit. And I suspect that Christoph Merkle���s finding about the financial crisis applies to losses caused by economic policy as well: the anticipation of them hurts us more than the actual experience.

Take identity out of it.

So far, I���ve avoided the terms ���Brexiter��� and ���Remainer���. There���s a reason for this. The nastiest disputes are those about identity: if you think you are underpaid and your boss doesn���t, you can negotiate but if you think he���s an arse and he thinks you���re a serial whiner, things will be more fraught.

For example, Simon says he is angry about Brexit because Brexiters are denying that economics can be knowledge. From one perspective, his anger is understandable: they are denying his (well-earned) identity as an economic expert.

But we can change the perspective. Brexiters don���t really support Brexit because of its economic benefits: belief in them is, as a I say, a halo effect rather than a rational or even sincere belief. Instead, they see Brexit as an intrinsic good, an expression of national sovereignty; this is why Sajid Javid thinks it ���self-evidently��� in the national interest. What we have (or should have) therefore is a dispute between two different conceptions, of intrinsic versus instrumental goods.

The Leaver-Remain divide is so bitter because it���s become not about our relations with Europe but a battle of identities, with the two sides now being proxies for other things. Remainers see Leavers as social conservatives; Leavers see Remainers as elitists.

Remember: identities can change.

Herein, though, lies a reason for optimism: political identities can change. If I���d told you a mere four years ago that I was a Remainer, you wouldn���t have known what I was on about. Back then, relations with the EU were a low-salience matter: only around 10% of voters (pdf) thought them the most important issue. And we could have had a civilized debate about them, had we been bothered to do so.

Our political identities can therefore change. It���s for this reason that a lot of the most passionate disputes in the past now seem hard for us to understand ��� for example ���wets vs dries��� in the Tory party or the battles over Clause IV or nuclear weapons in Labour. This gives us hope that a return to sanity is possible

There is, however, a problem here. The people who most need to know all of the above are those who are least likely to read it. The mainstream media seem keener to inflame passions than to dampen them.

A bit of me thinks the reason for this isn���t just to do with winning clickbait ��� something which the BBC, unforgiveably, seems as concerned about as the commercial media. Whilst we are divided about Brexit, we are not divided about something else ��� class. In this sense, Brexit hysteria suits our rulers just fine.

October 16, 2019

Why we are wrong

Eric Lonergan asked a good question yesterday: "why does it take so long for economic beliefs which are repeatedly falsified to change?" I can think of several reasons.

A failure to appreciate that the institutional background has changed.

Take, for example, big bonuses paid to bankers and CEOs. The idea that we need these to incentivize people is (mostly*) wrong. Instead, they crowd out other motives (pdf) such as professional ethics and can encourage excessive risk-taking.

In truth, though, investment bankers��� bonuses did not begin as an incentive at all. BITD when stockbrokers were owned by partners, they were instead a way of smoothing the partners��� earnings: in bad years, they could protect their incomes by cutting bonuses. They weren���t an incentive: having (often scary) partners looking over one���s shoulder was incentive enough.

In not appreciating sufficiently that the world has changed, people continue to believe that big bonuses are efficient, even though they might not be.

I suspect there are other examples here. Ideas such as the Nairu or output gap might have made sense in closed economies when inflation expectations were volatile. But they are less valid in open economies with stable expectations. And the idea of expansionary fiscal contractions made sense when private sector capital spending was constrained by high real interest rates and low profit margins, but is nonsense now we���re at the zero bound. And I suspect that some of those who champion the achievements of capitalism are insufficiently awake to the fact of stagnation now.

Bad ideas serve the rich.

There���s another reason why so many believe in the efficacy of high pay and big bonuses; they suit the well-off. And there���s never a shortage of people happy to defend their interests. As Adam Smith said:

The great mob of mankind are the admirers and worshippers, and, what may seem more extraordinary, most frequently the disinterested admirers and worshippers, of wealth and greatness

Bayesian conservatism.

It���s perfectly common for all of us to fail (pdf) to update our beliefs sufficiently in light of new evidence: this is one reason we see momentum effects and post-earnings announcement drift in stock markets. And it���s not unreasonable to err on the side of conservatism; new evidence can be unreliable and Burke was right to claim that there is the wisdom of ages.

Sadly, though, this reasonable motive can be amplified by others. Ego involvement causes us to cleave to strongly to an idea merely because we���ve expressed it ourselves. And groupthink causes us to stick to bad ideas if our colleagues do.

Sunk costs.

A friend recently showed me a rejection letter for a paper he���d written. Reviewer 2 claimed not to understand a section because it was ���purely descriptive.��� It was, of course, wholly comprehensible. What Reviewer 2 was doing was protecting his investment. He���d sunk his human capital into formal max U (pdf) modelling, and was damned if he was going to accept other ways of doing things**.

In this vein, if you���ve spent years solving DSGE models you���ll be loath to abandon them in favour of more useful approaches.

Few ideas are wholly false.

Take the efficient market hypothesis. It���s wrong, in the senses that defensive and momentum stocks do better than the EMH predicts, and that the aggregate market does sometimes over-react. But it is correct in predicting that active fund managers are mostly useless (or worse!). When faced with ideas of mixed truthiness, it���s easy to exaggerate their validity: it���s a form of halo effect ��� inferring from one quality that something possesses other ones.

The Duhem-Quine problem.

It���s rare that an idea is cleanly and wholly falsified; even the best experiments test joint hypotheses and are subject to the problem of external validity. This is even more true in macroeconomics. Does the lack of significant inflation in the face of low unemployment mean the idea of a Phillips curve is wrong, or are there just some variables which have confounded the relationship between unemployment and inflation? Is the weakness of western economies in the face of low real interest rates a sign that conventional monetary policy is futile, or does it just tell us that its impact has been outweighed by the forces of secular stagnation and declining profits? And so on.

���The poison is the dose���

The minimum wage has had little impact on labour demand. The Low Pay Commission says:

None of the research that we have commissioned has shown strong evidence that minimum wages have led to falling employment���[There is] some evidence of falling hours in response to higher minimum wages, but again the findings are not consistent across different specifications, and the effects are generally small.

This means opponents of the NMW were wrong to predict large adverse effects. But it doesn���t mean they���ll always be wrong. If we jacked the NMW up to ��50, they might well be right.

Our formative years matter

Our beliefs are disproportionately shaped by our formative years. Erin McGuire and Ulrike Malmendier (pdf) have separately shown that people who grew up in hard times own fewer equities than others even decades later (controlling for obvious confounders). Bad times in our impressionable years make us unduly worried about recessions.

I suspect this explains why the ECB has been too scared of inflation. Memories of the high and volatile inflation of the 70s and 80s have undue influence on the minds of 50- and 60-somethings.

We���re creatures of history

It���s not just our own personal histories that shape our beliefs. So too does the distant past. For example, David Fielding has shown (pdf) that, in the UK, people���s opinion of

21st century immigrants is significantly more positive when the respondents live in a constituency that was home to a medieval Jewish immigrant community. On average, these respondents also express less authoritarian views about crime and civil rights, and show less support for far-right political parties.

In this light, isn���t it plausible that German���s hostility to inflation should be based not so much upon current evidence as upon memories of the 20s?

If our beliefs are not formed by current evidence, why should they be changed by it?

Now, in saying all this I am NOT pretending these factors apply only to other people. I suspect I���m as prone to them as others. It���s just that it���s easier to see others��� errors than our own.

* I say mostly, because there is an exception. Big bonuses might deter bosses or bank traders from selling assets cheaply to rival firms.

** Anonymity cuts both ways. It enables you to dish out abuse, but also enables us to attribute the worst motives to you.

Chris Dillow's Blog

- Chris Dillow's profile

- 2 followers