Chris Dillow's Blog, page 27

October 9, 2019

Financialization as symptom

���To understand the person you have to know what was happening in the world when they were twenty.��� I was reminded of this (correct) line from Napoleon Bonaparte by reading Grace Blakeley���s Stolen.

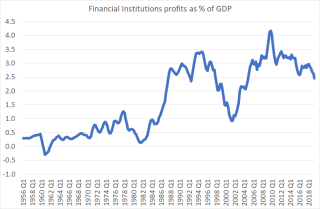

To an intelligent person of Grace���s generation, the defining event of one���s formative years was the financial crisis of 2007-09, which highlighted the fact that capitalism had indeed become financialized, in the sense that financial institutions play a much bigger role in driving booms and slumps than they did previously. One indicator of this process is the growth in profits of financial companies, from less 1% of GDP in the 50s and 60s to over 3% in the mid-00s*.

My generation of leftists, by contrast, was shaped by a crisis of non-financial capitalism ��� that of the 70s and early 80s. I therefore enjoyed Michael Roberts��� review of Stolen.

What I want to do here, though, is consider the links between these two crises. I agree with Grace that financialization ���has been driven by the logic of capitalism itself���. But I���m not sure she draws out the mechanisms here.

To see them, let���s start with the crisis of the 70s. Profits were then being squeezed by wage militancy. Thatcher���s response to this was to weaken labour���s bargaining power by (inadvertently!) creating mass unemployment, and reasserting ���management���s right to manage��� (a popular Tory slogan in the 80s).

But how does this restore profits? To see the possible mechanisms, let���s use a national accounts identity. GDP is equal to the sum of wages (W), profits (P) and taxes on production (T). It���s also equal to the sum of consumption (C), capital spending (I), government spending (G) and net exports (NX). Rearranging these gives us an identity for profits:

P = (C ��� W) + I + (G ��� T) + NX.

Profits can rise if and only if the right-hand terms rise. But how can this happen? One possibility is that more quiescent workers improve capitalists��� animal spirits and so raise I. Another is that lower wage growth and greater efficiency improve competitiveness and so raise NX. Both, though, are weak.

Leaving aside fiscal policy, this means that C ��� W is doing the work. Which highlights the problem. Bashing workers ��� by raising unemployment and cutting labour���s share of GDP ��� does not, in itself, raise profits if workers cut their spending. As Michal Kalecki said, ���a reduction of wages does not constitute a way out of depression���.

Which is where financialization comes in. The defining event on the road to financialization in the 80s was not big bang: at the time, this was seen as merely the ending of a restrictive practice rather than the start of the creation of global investment banks. Instead, it was the credit liberalization of the early 80s, which made mortgages and consumer credit much easier to get.

This did not merely increase the activity and hence profits of lenders: note the big rise in financial profits in the mid-80s. It did something even better for capitalism. In allowing workers to borrow more it raised C ��� W and thus boosted profits: the household savings ratio slumped in the 80s.

In this sense, financialization was a solution to a crisis in the real capitalist economy ��� albeit one discovered by accident.

But it was only a temporary solution. Even with the most liberal credit conditions, there is a limit to how much people can borrow and how far C ��� W can rise. Worse still, the inequality unleashed by Thatcher in the 80s had a detrimental effect upon productivity and investment. (Grace says that inequality depressed growth by transferring income to people with a low propensity to consume, but I fear this understates the many other mechanisms whereby inequality harms output). Alongside other factors depressing capital spending ��� such as the fact that capitalists had learned that investment doesn���t pay ��� the result was that by 2005 Fed chairman Ben Bernanke was complaining about a ���dearth of domestic investment opportunities��� in the west.

This gave another spur to financialization. It meant that the Asian savings glut was invested not into productive real projects in the west but instead into Treasury bonds, which reduced their yields and hence facilitated the creation of mortgage derivatives. As Adam Tooze wrote:

Emerging market investors bought first Treasuries and then GSE-issued agency debt. This left other institutional investors looking for alternatives. What filled the gap was financial engineering. If pension funds, life insurers and the managers of the gigantic cash pools accumulated by profitable corporations and the ultrawealthy needed safe assets, AAA-rated securities were a product America���s mortgage machine knew how to synthesize. (Crashed, p59)

In this sense as well, financialization is the result of a crisis in the real capitalist economy; the lack of real investment opportunities meant that cheap money flowed into the financial sector instead. As Ravi Jagannathan has said (pdf), the crisis was a symptom.

Financialization, then, is not a Bad Thing done by Bad People. It is instead an endogenous response to a longstanding crisis of real capitalism.

* My chart uses ONS code identifiers NHCZ and YBHA. This measures the profits generated in the UK by financial companies, so excludes the foreign profits of UK-based banks.

October 6, 2019

On commodification

It���s a sign of our times that one of the more insightful comments this week should come not from our debased media but from a minor royal. Prince Harry���s complaint that his mother and wife have been ���commoditised to the point that they are no longer treated or seen as a real person��� hints at an important aspect of capitalism ��� commodification.

This is the process whereby people and social relations are marketized and turned into goods and services to be bought and sold. Capitalism ���has left remaining no other nexus between man and man than naked self-interest, than callous ���cash payment������ wrote Marx and Engels. ���It has resolved personal worth into exchange value.���

Very broadly speaking, there are two types of commodification. One is endogenous such as in the case Harry is complaining of, whereby the media treat its subjects (in some cases with their cooperation) as commodities to be used to sell papers. Another example is when non-monetary motives such as professional pride are displaced by financial ones. Yet another is when internet companies such as Facebook and Google convert data about their customers into something they can sell to advertisers.

A second type of commodification occurs with state assistance. One huge way in which this occurred was through the privatization of land, via the dissolution of the monasteries and enclosure acts. These helped create not only markets in land, but also in labour (pdf) as peasant farmers were driven into the industrial labour force. This process is still going on. Other examples are: privatization and outsourcing; the imposition of tuition fees which have converted universities into commodities; copyright laws which allow capitalists to commoditize elements of music; and low state pensions which have given space to companies to sell over-priced private pension management.

Many of these moves are a response to capitalist stagnation. Profit rates (pdf) have been in long-term decline. This means capitalists need the state to help it create new markets, new ways of making profits.

You might wonder: what���s so bad about all this? After all, markets are often a great way of allocating goods and services efficiently.

One problem is that this is not always the case. Commodified universities are in many respects worse than their predecessors, offering devalued degrees and shoddy research. Financial motives can produce worse behaviour and less innovation than intrinsic motives. And sometimes the state is just better at doing things than the private sector: this, I think, is true of pension provision.

The second problem is that markets change culture. Sometimes, this is for the better. As Dierdre McCloskey has argued, they can promote bourgeois virtues. But not always. G.A Cohen has written:

The market posture is greedy and fearful in that one���s opposite-number marketeers are predominantly seen as possible sources of enrichment, and as threats to one���s success. These are horrible ways of seeing people���The market is intrinsically repugnant.��� (Why Not Socialism? p40)

Whether Cohen or McCloskey is correct depends upon context. In the context Prince Harry is speaking, Cohen���s right. Farmers��� markets, by contrast, vindicate McCloskey. There���s a big difference between a healthy commercial society and rapacious capitalism. For this reason some forms of decommodification are to be welcomed, be they Parkrun, LETS or proposals for abolishing tuition fees or introducing universal basic services (pdf).

My point here is twofold, and should be (but perhaps isn���t) trivial. First, the creation of markets is often not a natural process, but often involves heavy state intervention. And secondly, the question of whether goods and services should be allocated by market, state or voluntary cooperation is not merely an arid technocratic one but one which shapes future culture and morals.

September 18, 2019

The trouble with capitalism

Are the faults of capitalism curable, or are they instead symptoms of a chronic disease? This is the question posed by Martin Wolf:

What we increasingly seem to have���is an unstable rentier capitalism, weakened competition, feeble productivity growth, high inequality and, not coincidentally, an increasingly degraded democracy.

There is much to admire in this piece. But I fear it understates the problem with capitalism.

The Bank of England has given us a big clue here. It points out that the rising profit share (a strong sign of increased monopoly) is largely confined to the US. In the UK, the share of profits in GDP has flatlined in recent years. Few, however, would argue that UK capitalism is less dysfunctional than its US counterpart. Which suggests that the problem with capitalism is not increased monopoly.

So what is it? Here, I commend some brilliant work by Michael Roberts. Many of the faults Martin discusses have their origin in a declining rate of profit (pdf) ��� a decline which became acute in the 1970s but which was never wholly reversed.

The causes of this decline are many and debated: an over-accumulation of capital in the 1960s and again in the tech bubble; increased worker militancy in the 60s and 70s; greater competition both from overseas and internally (see for example William Nordhaus���s work); a slower rate of innovation in many sectors; an inability of shareholder-owned firms to exploit potential profit opportunities; weak aggregate demand; and so on.

Granted, actually measuring the rate of profit is fraught with difficulty, due to myriad problems in measuring the capital stock. But the fact that capital spending has been weak for many years (before Brexit) suggests that incentives to invest are weak ��� one plausible reason for which is low profitability.

The financial crisis was a symptom of this. Imagine there had been an abundance of profitable investment projects in the real economy in the early 00s. The savings glut and fall in bond yields would then have financed these so we���d have seen a boom in investment, jobs and incomes. But there was no such abundance, so the savings glut instead financed a bubble in housing and credit derivatives which ended in crisis.

Many of the things social democrats like Martin deplore about capitalism are in fact responses since the late 70s to this crisis of profitability. The assertion of management power ��� a symptom of which is high CEO salaries (pdf) ��� is a (successful) suppression of worker militancy. Privatizations are an attempt to expand the realm in which capitalists can make profits. Financialization is the result of a shift away from low-profit activities in the real economy. And rent-seeking and cronyism reflect attempts to sustain profits in the face of competition and crisis.

Stagnant productivity tells us that these measures have not wholly worked, in part perhaps because the same inequality* they have generated tends to depress productivity growth.

If all this is true, or roughly so, then the problems Martin describes are not so easily cured. When Martin says that ���fixing this is a challenge for us all��� he is understating the case.

But is it true? The way to find out is to see if attempts to reform capitalism actually succeed. Mirabile dictu, there are even some proposals here that do not come from the left. Sadly, though, one effect of capitalism���s crisis has been, as Martin says, to so degrade democracy as to take intelligent economic policy off the agenda.

* Yes, UK inequality stopped rising a few years ago. But the damage it does is still with us. If a man has been hit by a bus, you do not restore him to health merely by stopping the bus.

September 17, 2019

A start, or an end?

Sometimes, the simplest questions get overlooked. Just as we must always ask of any statistic ���is that a big number or not?��� so we must ask of any policy: is it the end or the start?

I ask because of a recent ComRes poll which found that 48% of voters agree with the statement ���I ���don���t really care whether or not or how the UK leaves the EU, I just want the uncertainty to be over.���

But of course, it is nonsensical to think a no-deal Brexit will end the uncertainty. Instead, as Tom Kibasi says, it will mean ���a decade of Brexit, Brexit and more Brexit.��� No deal is the start of a process, not the end.

There are other policies where we should ask the same question: is this the start or the end? For example:

- Nationalization. Viewed as an end, this is just a way for the state to seize dividends. But we should instead see it as the start of the transformation of businesses. For the left, this means managing them in a (well-defined) conception of the public interest. For the right, by contrast, it raises the danger of sloppier management. A big criticism of the part-nationalization of Lloyds and RBS is that it missed the opportunity to change the way banks are run. It was an end, not a start.

- Labour���s plan to give workers a 10% stake in the business they work for. Viewed as an end, this is small beer ��� a small dividend cheque for workers, a small dilution of current owners. It���s merit, however, lies in the hope that it is the start of something. Giving workers a stake might raise productivity, and lead to demands for a bigger stake and more control. As Tocqueville wrote:

Democracy does not give the people the most skilful government, but it produces what the ablest governments are frequently unable to create: namely, an all-pervading and restless activity, a superabundant force, and an energy which is inseparable from it and which may, however unfavorable circumstances may be, produce wonders. These are the true advantages of democracy.

- Scrapping tuition fees. Viewed as an end, this is mildly regressive. It���s merit, however, lies in it being a start. It���s part of what James Meadway has called decommodification ��� an expansion of the realm in which market values do not dominate. And, over time, it could return universities to their traditional educative function and prevent them being mere consumer experiences wherein the customer is king.

- Basic income. As an end, this is technocratic welfare reform of dubious merit. But as Guy Standing says, its value lies instead in it triggering longer-term cultural change:

People who have basic security become more altruistic and tolerant, and thus better citizens. Basic income also strengthens resilience to life���s shocks and hazards. In reducing feelings of stress���it not only improves health and thus frees up money for other purposes or needs, but it also leads to more rational and long-term decision-making.

This is why experiments on basic income, whilst valuable, don���t tell us the whole story, as they haven���t run for long enough, or been widespread enough, to capture such potential change.

This is not to say that all policies are starts rather than ends. One criticism of New Labour is that too many of its policies, whilst welcome in themselves, were ends rather than starts. Increased public spending did improve public services, but such improvements lasted only as long as the Labour government did. And whilst the ���terror and targets��� style of management might have had a few short-run efficiency gains, these stopped when people learned to game the system, and when hierarchical managerialism crowded out goodwill and intrinsic motivations.

My point here is to echo Derek Wall���s recent interpretation (reviewed here) of Elinor Ostrom���s work. For here, he writes, ���a core goal of public policy should be to facilitate the development of institutions that help bring out the best in humans��� ��� that is, ones that enable and encourage free cooperation.

And herein lies a paradox. Most people agree that institutions shape behaviour ��� be it righties complaining that welfare states create a dependency culture, lefties complaining that neoliberalism makes us mean and selfish, or McCloskeyites and Smithians describing how commerce fosters virtue. And yet despite this, there is little explicit political thinking about which policies and institutions might best be a way of starting a journey to a good society,

Of course, bounded rationality means there���s a (tight?) limit to what such thinking might accomplish. And as Ostrom���s work showed, the devil is in the detail and the context. But nevertheless, there is an alternative way of thinking here. There should be more to politics than mindless ���customer is king��� consumerism.

September 12, 2019

Doubting disaster capitalism

A report from Byline Media has prompted talk that Brexit is an example of disaster capitalism: it is supported by vulture investors who hope to profit from economic turmoil. I���m sceptical of this.

For one thing, I���m not sure the data supports this claim. Take, for example, the publicly-declared short positions taken by Crispin Odey���s firm, Mr Odey being one of Brexit���s biggest backers. These are not so much in firms that���ll be hard hit by Brexit but instead in those that are troubled already ��� such as Debenhams, Intu, Metro Bank and IQE. Betting against these isn���t especially clever or sinister. It���s just a bet on momentum ��� that past losers continue to lose money ��� and on a continuation of the pattern uncovered years ago by John Campbell, that distress risk doesn���t pay.

That Odey is using such humdrum strategies draw our attention to a big problem with the idea of disaster capitalism. It���s that fund managers are not evil geniuses. The performance of most hedge funds has for years been mediocre. Hedge Fund Research, for example, estimates that equity hedge funds have made only 4% per year over the last five years. And indeed, some of Mr Odey���s funds have done much worse than this: his Odyssey fund has lost a lot.

What���s true of hedge fund managers is true (pdf) of long-only ones too. The FCA has concluded that these ���did not outperform their own benchmarks after fees.��� And City University���s David Blake (pdf) has found that "the vast majority of fund managers in our data set were not simply unlucky, they were genuinely unskilled."

Such evidence is a big problem for the ���disaster capitalism��� theory. Yes, it is likely that the uncertainty caused by a no-deal Brexit will cause some companies to be mispriced, just as the shock of the 2016 referendum result did*. And some people will make money from this, just as a few capitalists occasionally do well at any time.

But the idea that there���s a cabal of masterminds engineering Brexit in order to profit from such mispricings seems implausible. As every equity investor knows, there���s a world of difference between knowing that there are some mispricings out there and being able to profit from them. The record shows that fund managers lack the skills to do so.

Yes, some Brexiters have taken aggressive positions. But I suspect this is an example of correlation without causality. Support for a hard Brexit is an out-of-consensus position among financiers, most of whom back Remain. And people who take contra-consensus views on one thing are likely to take aggressive positions on other things. But this doesn���t mean they are right.

In truth, there���s a good reason why most financiers favour Remain. Fund managers make their money not so much from clever trading as from attracting clients. They are asset gatherers more than fund managers. The best way to increase funds under management is for the economy to do as well as possible, so that mugs potential clients have both the cash and risk appetite to invest in funds. Remain is in the interests of most fund managers. Not everything is a zero sum game.

* It might well cut the prices of many stocks but in most cases this will be because it reduces future earnings too.

September 8, 2019

On Tory paradoxes

There are two great paradoxes about the Tory party.

Paradox one is that whilst neoliberalism has triumphed, the Tories have lost their intellectual hegemony. Matthew Parris says Johnson is a symptom not a cause of the Tory meltdown. That echoes James Butler���s claim that ���the Conservative Party is in a process of ideological decline��� and Stian Westlake���s that the Tories ���have stopped talking and thinking about economics.��� This week, 82 academics wrote to the FT defending Labour���s economic policies. It is difficult to imagine a similarly large and eminent group defending Tory policies. The Tories��� picturing of Corbyn as a chicken is a great illustration ��� not of Corbyn but of their own lack of seriousness.

Paradox two is that this lack of intellectual vitality hasn���t much reduced Tory popularity: they still have a lead over Labour in most opinion polls.

To understand these paradoxes, let���s start by realizing that the dominance of neoliberalism poses a problem for the Tories. Whilst it has served the 1% very well, it has alienated many who might otherwise support the Tories. The financialization of the housing market has made property unaffordable for millions of young people, and managerialism has degraded the work of many professionals. Parts of the ���middle class��� have become proletarianized. And they vote accordingly.

Also, neoliberalism has caused productivity growth to stagnate. As Richard Seymour says, this has turned smaller capitalists from ardent Thatcherites into Poujadiste Ukippers. As Ben Friedman showed, stagnation leads to reaction and intolerance.

Osbornomics exacerbated these problems. In saddling graduates with huge debts, it merely proletarianized them further. And in depressing demand, austerlty exacerbated the squeeze on productivity and incomes; low interest rates have clobbered older people���s savings.

Faced with these trends, the Tories have only two responses. One is what Stian calls ���home office economics��� ��� the mindless authoritarianism of May. The other is that of the Britannia Unchained crew of Raab, Patel and Kwarteng - a doubling down on calls for deregulation. Neither is a viable strategy.

This leaves the Tories with a problem. If wealth and power are concentrated, how can you create widespread support for the party that defends the existing economic order?

The answer is to change the subject.

If the Tories talk about economics, it���ll remind people that their rents are astronomical, that they can���t afford a house, that they haven���t had a decent pay rise for years, that their business is struggling and that their savings income has shrunk to nothing. The solution, then, is not to talk about economics. As Philips Stephens says, Johnson wants to frame the election in terms of nationalism, xenophobia and ���people vs parliament.��� This is why Fiona Bruce was so quick to silence Emily Thornberry when she started to mention food banks; the Tories don���t want to talk about the economy. Their best hope is to shift the debate onto cultural and identity politics.

From this perspective, my second paradox isn���t a puzzle. The Tories are popular not despite their lack of economic ideas, but because of it. This intellectual vacuum is being filled by things that play to their strengths ��� populist demagoguery. The people have had enough of experts.

In this sense, the Tories need economic stagnation as it keeps alive atavistic nativist impulses. In France Poujadism melted like snow on a spring day as the French economy boomed in the late 50s and 60s. The Tories don���t want their brand of Poujadism to go the same way. Stagnation suits them.

This highlights another paradox about politics ��� that sometimes, failure succeeds. For example, anti-immigration politicians need to keep migration in the public eye, which means failing to control it. Politicians who use crime and terrorism to justify curbing freedom need to keep alive the threat of terrorism. Parties who draw their support from the poor need to maintain poverty. And so on.

The Tories, then, are beneficiaries of their own failure.

September 5, 2019

Capitalists for Corbyn

The Telegraph says some (a few) investment bankers would prefer a Corbyn government to a no-deal Brexit. There are good reasons for this.

This sounds a strange thing to say, given some of Labour���s rhetoric and their proposals for higher corporate and top income taxes; the nationalization of utilities; the dilution of current shareholders��� ownership; and strict restrictions (pdf) on property speculation. It���s also the case that finance has been very happy with the post-2010 mix of fiscal conservatism and monetary activism, which Labour will end.

Despite all this, a Corbyn government offers some things which look unlikely under Johnson.

One is a degree of stability. Of course, Corbyn cannot offer swift certainty about the course of Brexit. But he will take the worst-case scenario of no-deal Brexit off the table. And in trade talks with the EU he is likely to put greater weight than the Tories on economic interests than on conceptions of sovereignty. Johnson���s ���fuck business��� remark showed that he prioritizes nationalism over commerce. Corbyn won���t do this.

This matters. Uncertainty, as Nick Bloom has shown, is bad for investment, productivity and growth. And as I���ve said, it���s also bad for equity valuations. We���ve known for years that markets hate uncertainty, and that people will pay a high price to reduce it. For some capitalists, Corbyn is that price.

A second thing Labour offers is a degree of economic growth. It at least knows that productivity has stagnated for more than ten years and is thinking about how to react to this. We know from the experience of the 1950s and 60s and from recent European history that capitalist economies can thrive with highish personal taxes, a degree of co-determination, and big public sectors. Capitalism does not require small government or neoliberalism.

Of course, the experience of the US economy and S&P 500 since the 80s suggests that profit-led growth is best (pdf) for capitalists. But sometimes (pdf), this is not an option ��� if, like now, pro-capitalist policies fail to induce strong rises in capital spending. When this is the case, wage-led (pdf) growth (pdf) is a reasonable second-best. And Labour offers the chance ��� only chance ��� of this.

But there���s something else. Successful capitalism requires not just growth but also legitimacy. It���s not accident that, from the late 19th century onwards, almost all capitalist states developed degrees of redistributive taxation and welfare states. These were necessary to buy off public discontent. Something similar might be needed today. High inequality, crumbling public services and the inflicting of uncertainty and harassment upon millions of residents risk undermining public support for the existing order. In tackling these, Labour will help shore up the legitimacy of some sort of capitalist system.

From this perspective, a Labour government offers capitalists a form of inoculation: a small illness to prevent a worse one.

Or, to change the metaphor, parasites need a healthy host. The more intelligent members of the capitalist class ��� who are perhaps under-represented in the media ��� are not hyperventilating hysterics and so can see this.

It tells us a lot about the degenerate state of the Tory party that it might be less able than Corbyn to offer capitalism what it needs.

September 3, 2019

What theft?

There���s some hyperventilating about Labour economic plans. At CapX Tim Worstall says that John McDonnell���s proposal to give private tenants a right to buy their home at a discount is ���straight out theft.��� And the FT says Labour plans to confiscate ��300bn of shares*.

Such claims are, I think, an exaggeration.

Let���s take private tenants first. The problem here is that house prices are high in large part because of policy mistakes. We can disagree upon what the precise failure is ��� restrictive planning laws, promotion of financialization, inadequate public building or insufficient taxation of land. But both left and right would agree that high house prices are, at least in part, due to errors of commission or omission by successive governments.

Which poses the question: does anybody really have a right to profit from bad policy? I���m not sure. If they do, it requires some argument which Tim doesn���t supply. In the absence of such a right, there can be no ���theft���. What McDonnell is instead proposing is a different sharing out of the profits of state failure.

This is not to say his proposal is a good idea. It���s not. It gives a windfall to a group ��� present tenants ��� which is just as arbitrary as the beneficiaries of state failure. And it���s not clear that expanding owner occupation is a good idea. Andrew Oswald and Danny Blanchflower have shown that higher rates of owner occupation are associated with higher unemployment and lower investment ��� because owner occupiers are less able to move to where there are jobs, and more likely to resist commercial and industrial developments in their area. And there���s also evidence that more mortgage lending ��� an obvious corollary of more owner occupation ��� can crowd out productive business loans.

Labour���s best proposals on land reform ��� Land for the Many (pdf) ��� did not propose a right to buy, and rightly so I think.

The FT���s claim that Labour would ���confiscate��� share is, I fear, an egregious error. What the party is proposing is a gradual dilution (of 1% a year) of existing ownership and corresponding expansion in worker ownership. This is not so much a confiscation as a transfer: the headline could equally well be ���Labour to give workers ��300bn windfall.��� The FT is in this sense committing a common error ��� of describing something as a cost when it is in fact a transfer.

And, indeed, it���s possible that this won���t cost current business owners anything. We have good evidence that worker ownership (pdf) can boost productivity simply by giving employees more skin in the game. And Labour���s plan might in the long-run be especially successful in this as it would expand public support for business-friendly policies. More efficient companies would be in everybody���s interest.

If you want to make a coherent case against Labour���s plans, you shouldn���t talk about theft, but rather show evidence that worker ownership would not be as beneficial as I think.

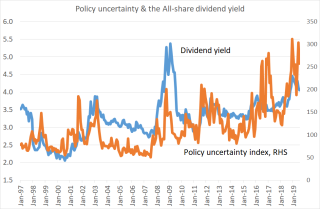

In fact, in whining about Labour���s ���confiscation��� and ���theft��� distracts us from what is a bigger and more genuine destruction of wealth. My chart shows the point. It shows that there���s a strong correlation (0.56 since data began in 1997) between the dividend yield on the All-share index and global policy uncertainty, as measured by Nick Bloom and colleagues. The clich�� is right: markets really do hate uncertainty. It means lower share prices.

Uncertainty now is unusually high, which is costing investors billions. If uncertainty were at its 1997-2015 average, the relationship in my chart implies that the dividend yield on the All-share index would be almost a percentage point lower than it is. Which means that share prices would be ��700bn higher than they are**.

The uncertainty created by Brexit and by Trump���s trade wars is, therefore, costing people vastly more than Labour��� plans. If you must complain about theft and confiscation, complain about this instead.

*The original headline to that piece was Labour ���would cost UK companies ��300bn.��� That was obvious drivel, and the FT has rightly amended it.

This calculation is very rough. On the one hand, it understates the cost of uncertain. If we had less of it, capital spending and economic activity would be higher, which would mean dividends would be higher. But on the other hand, there might be some omitted variables which help explain the link between uncertainty and equity valuations. To the extent that there are, I might well be over-estimating the impact of uncertainty on yields. Net, though, I very much doubt that the impact of uncertainty upon valuations is small enough to ignore, as Brexiters and Trumpites are doing.

August 31, 2019

The theatre of politics

In the latest episode of Great Lives, Shaun Ley says he likes the ���theatre��� of politics. This helps explain many of the failings of political reporting.

Mr Ley is not, I suspect, unusual here. When ITV���s Paul Brand said that Johnson���s ���press conferences are 100 times more engaging than Theresa May's���, he was praising Johnson���s theatrical skills, as was Robert Peston is his fawning report. And a lot of you were unhappy with coverage of last week���s G7 conference because it focused upon the theatre of the occasion more than the substance.

Presenting politics as theatre is, however, dangerous and misleading. Ian Leslie gives us one reason. Being an attractive character is good theatre, but it is no guide to whether one is actually competent: Johnson���s success is founded largely upon appearing likeable (at least to a particular, influential group) rather than upon any track record of excellence in office. Worse still, we are bad at judging likeability, a fact conmen and psychopaths profit from.

But there���s something else. When journalists foreground the theatre of politics they background other important things.

Some of these are facts and interests. Paying attention to the personal chemistry between Johnson and other leaders disguises the fact that there are massive structural barriers to renegotiating the Brexit deal, such as the Irish border trilemma, the EU���s desire to maintain the integrity of the single market, and the refusal to renegotiate the backstop.

Other things are long-term emergent developments. Capitalist stagnation and negative real yields should be the key determinants of macroeconomic policy. But these get neglected when journalists focus instead upon the theatre of ad hoc policy announcements, Chancellor���s intentions and their relations with Number 10.

Yet other things are basic ground truths. Fiscal austerity has cost every household thousands of pounds, caused thousands of deaths, driven the most vulnerable to despair and suicide, weakened important institutions and given us Brexit with all its costs. And yet many of its architects and supporters have retained their ���credibility��� with the media, because they���ve played the theatre well.

There is, of course, a class aspect here. Just as Shakespeare is usually performed with plummy voices rather than in the (to me, more comprehensible) accent Shakespeare used, so the theatre of politics is best done by poshos: would Johnson, Cox or Rees-Mogg sound as ���credible��� if they had cockney or Scouse accents?

The problem here is not the failings of individual journalists. It is instead inherent in the industry. Journalism values ���human interest��� stories and the lively anecdote, quote and image ��� all of which are essential parts of theatre. These, however, impart a systematic bias if we rely too heavily upon them to report political affairs.

Psychologists have identified a widespread mistake people make; we often over-rate character and intentions as explanations for behaviour and underweight external environmental factors, They call it the fundamental attribution error. In treating politics as theatre, the media institutionalises the error.

August 29, 2019

The fanaticism threat

Our problem is not so much what people believe as the intensity and fanaticism with which they believe it.

For example, support for some kind of Brexit is a tenable position. But is a no-deal Brexit really worth the damage to social cohesion, the economy, the constitution and the GFA? Surely, only a fanatic would think so. Equally, on the Remain side the fact that Brexit has a popular mandate must mitigate the vehemence of one���s views ��� and yet in too many cases it does not. The upshot of such fanaticism on both sides is that a compromise position ��� a soft Brexit ��� has long ceased to be an option despite its potential popularity.

Which poses the question. Why has fanaticism increased so much about ��� remember ��� a matter that was a low priority (pdf) only four years ago?

A lot of cognitive biases are at work. One is a form of what Dan Ariely calls the Ikea effect (pdf). If something costs us a lot of time and effort we infer not that it���s too much trouble, as economic rationality suggests, but that it must be even more valuable than we thought. The difficulty of achieving Brexit (or Remain) thus becomes a reason for valuing it more highly.

Another is asymmetric Bayesianism, our tendency to downplay dissonant evidence whilst overweighting that which supports our position. The upshot of this is that the more we learn about an issue the more polarized our attitudes become.

Relatedly, there���s a backlash effect. If our opponents seem unreasonable and intransigent, we are apt to become so ourselves by disregarding any worthwhile points they make and asking: why should I be the one to compromise?

A further factor is a form of selection effect. Our mass media selects for the shrillest voices either by giving their readers what they want to see, or by chasing clickbait, or because producers think a shouting match is good TV or radio.

On top of this, however, Brexit has become a matter of identity. ���Leaver��� and ���Remainer��� no longer describe merely one���s attitude to the EU, but a host of other attitudes, towards immigration, climate change, the death penalty and so on. And arguments about identity are often much more fraught than ones about mere money (though of course the distinction between material interests and identity is blurred).

The background against which all this is happening also matters ��� that of economic stagnation. Back in 2006 Ben Friedman showed that economic weakness led to a weakening of liberal-democratic values. One reason for this, I suspect, is that if the economic pie isn���t growing then any disagreement becomes a zero-sum game: victory for me means defeat for you. This fosters a more conflictual culture even on issues that are not ostensibly about money. (This is why I have little time for many centrist MPs, who claim to value liberal democracy whilst paying no heed to the economic base that fosters such values).

All of this brings me to Paul Evans��� point:

We no longer have an established understanding of what the pre-conditions for a good democracy are.

Such conditions, I suspect, are not merely institutions and laws. They also require the right character. A healthy democracy requires that we have the capacity for cool, rational(ish) deliberation. Among many other things this requires that we be able to stand back from our own views and to understand others���: what Rorty called liberal irony (pdf) and what Smith called sympathy (pdf).

Such virtues are now scarce. One hope, however, might be that passions which are easily inflamed can sometimes just as easily die away. But this is only a hope.

Another thing: It would be a clich�� to quote Yeats��� line about the worst being full of passionate intensity. I mention this only to point out the distinction of his brother Jack: he became the first man from independent Ireland to win an Olympic medal ��� for the painting which illustrates this piece.

And another thing: if you think there���s any irony in a Marxist pointing out the dangers of fanaticism, you perhaps know little about Marxism or the human condition.

Chris Dillow's Blog

- Chris Dillow's profile

- 2 followers