Chris Dillow's Blog, page 28

August 27, 2019

Origins of Corbynphobia

Why is there so much passionate, visceral hatred of Jeremy Corbyn? From an economic point of view, it seems a puzzle.

His stated economic programme is modest. As James Meadway says, to large extent, ���Corbynomics is Make Britain Normal Again��� ��� to make us more like an ordinary European social democracy. No credible analysis would put the cost of this at anywhere near the cost of austerity or of a no-deal Brexit. And yet, it seems to me, hatred of Corbyn is disproportionate to this programme. Why?

I���m not sure about Phil���s claim that the capitalist class senses an existential threat. For one thing, whilst the haute bourgeoisie are of course opposed to Corbyn, the most violent hostility to him comes from smaller rentiers and those on comfortable but not astronomic salaries. And for another, Corbynites hopes for a shift in incomes from profits to wages (pdf) and a definancialization of the housing market might (only might) be compatible (pdf) with a healthy (pdf) capitalism.

I suspect, then, that something else is going on.

In part, it is simple habituation. We���ve got accustomed to the cost of austerity and are resigning ourselves to no-deal. These are the devils we know. But Corbyn is the devil we don���t. Also, there���s an adverse halo effect: Corbyn���s associations with terrorists and Putinphiles cause some to fear that such bad judgement will infect his policies generally. Perhaps, relatedly, there is mythmaking. Some of Corbyn���s critics sound like the Self-Righteous Brothers: ���if that Corbyn comes in here nationalizing the pie shops, giving all our money to lesbians and turning us into Venezuela, I���ll go: ���Oi, Corbyn, no.������

But I suspect there���s something else. It goes back at least as far as Thomas Hobbes, who saw society as ���a war of every man against every man.��� What concerns us is not just the absolute level of income but rather our income relative to others. Back in 1995 Sara Solnick and David Hemenway found (pdf) that more than half of people would prefer an income of $50,000 a year when everybody else gets $25,000 than one of $100,000 when others get $200,000. Andrew Clark and Andrew Oswald (pdf), Robert Frank (pdf) and Erzo Luttmer (pdf) among others have found a similar thing. The worker who asked his boss ���if you can���t give me a pay rise can���t you give everybody else a pay cut?��� wasn���t atypical.

In fact, Eric Falkenstein has argued that it is this concern for relative wealth that explains one of the biggest puzzles in financial economics ��� of why there often is not a trade-off between risk (pdf) and return. If we care not about losing money but rather about losing relative to others, all risk becomes idiosyncratic and hence unpriced.

From this perspective, economic insecurity is not something felt only by the poor. Someone on a high income, but who has experienced a relative decline ��� or who fears one ��� also feels it; this might help explain why support for populism isn���t confined to the worst-off.

Herein, I think, lies a foundation of hostility towards Corbyn. It is rooted in a fear of a loss of relative income. The issue here is not merely tax rises, but also of status more generally. After five years of a Corbyn government, would the relative socio-economic position of older, wealthier white men be as high as now?

New Labour tried to allay such status anxiety by pledging not to raise top tax rates. Corbyn is not doing so. Which means that, for some, he is threatening something much worse than a weaker economy.

August 21, 2019

Smart consumers. stupid voters

What do ordinary folk know about economics? This question has been revived by Simon, who argues that support for a no-deal Brexit is based upon ���information failure��� caused by our biased and inadequate media. This is in a similar spirit to Jason Brennan and Bryan Caplan, who argue in different ways that voters are irrational and/or misinformed.

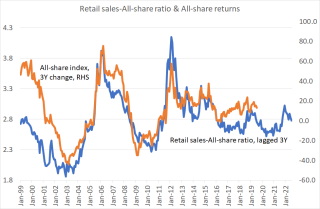

My chart offers a corrective to this view. It shows that the ratio of retail sales to share prices has been a fantastic predictor of equity returns since the current vintage of retail sales data began in 1996. The correlation between the ratio of retail sales to the All-share index and subsequent three-year changes in that index has been a whopping 0.76 since 1996.

Ordinary people, then, know something very important. In aggregate, they know where the stock market is going.

I���m not saying anything new or original here. My chart is merely a simplification of work by the Bank of England and by Martin Lettau and Sydney Ludvigson (pdf) which shows that consumer spending predicts equity returns.

There���s a simple reason for this. Consumer spending is forward-looking: if we expect good times, we���ll spend more than if we fear the sack or a pay cut. When spending is high, therefore, it predicts good times and when it���s low it predicts bad. For this reason, there���s also a strong correlation (0.48) between the retail sales-All-share ratio and subsequent three-yearly changes in manufacturing output, an indicator of cyclical conditions.

Of course, if you take any individual consumer, s/he might well be ill-informed or irrational. But across millions of them such errors will cancel out. There���s sometimes wisdom in crowds.

Now, you might object that my chart overstates this wisdom. Share prices tend to over-react, rising and falling too much. This means that their ratio to any stable indicator ��� even a time-trend ��� will also predict subsequent returns.

True. But irrelevant. The fact that shares over-react and can be predicted by consumer spending tells us that ordinary folk know more than the so-called expert fund managers who move share prices.

The people, then, can be smarter than elites.

How can we reconcile this with Simon���s depiction of many of them as know-nothings? Simple. There are, in my context, at least three big differences between consumers and voters.

First, consumers don���t need to know why things are happening. They only need a feel ��� often inarticulable ��� of what might happen. If we ask them in aggregate ���where���s the economy going?��� they can tell us. If we ask why, we might well get nonsense. David Leiser has shown one reason for this. People, he says, are terrible at making connections between economic events. For example, they fail to blame austerity for low returns on their savings. Instead, they often believe that good begets good. So, if you think Brexit is a good thing, perhaps for reasons independent of economics, you���ll be tempted to think it���ll have good economic effects: wishful thinking is powerful and ubiquitous.

Secondly, consumers have skin in the game whereas voters (as individuals) do not. If you spend too much or too little, you suffer. If you have a stupid opinion about politics, however, you don���t because your opinion doesn���t alter the outcome. In this way, consumers are incentivized to think whereas voters are not.

Thirdly, consumers��� errors are largely uncorrelated ��� except to the extent that there are peer effects or information cascades. Voters��� errors, however, can be correlated thanks to the influence of the mass media. One of the key conditions for there to be wisdom in crowds is therefore more likely to hold for consumers (at least in the circumstance I���ve described) than for voters.

All this poses a big and under-appreciated question: how might we change our political institutions so that we���ve more chance of mobilizing the disaggregated wisdom of people whilst filtering out the madness of crowds.

Representative democracy, with MPs acting as Burkean filters against poor judgment used to be one, albeit very imperfect mechanism. It���s now clear, though, that we need others which might well include some form of deliberative democracy (pdf). With a few honourable exceptions - such as Paul Evans - nobody seems much interested in this issue, however. As long as our side wins, we don't care about the rules of the game or its health.

August 18, 2019

The dubious logic of commodification

The proposal to raise the pension age to 75 reminds us of an under-appreciated fact ��� that there is, at least sometimes, a conflict between human flourishing and economic rationality on the one hand and the logic of capitalist accumulation on the other.

We can immediately dispense with the claim that working longer is good for our mental and physical health. If this is the case, it is a reason for banning age discrimination and encouraging lifelong learning so that older people���s skills don���t become obsolete - in short, for giving people the real choice of how long to work. ���Forcing people to be free��� used to be a very unconservative idea*.

To understand what���s going on here, we need a Marxian notion ��� that of commodification. This is the process of turning objects and relationships which are outside the realm of market transactions into commodities which can be exchanged at a profit. It is is one of the major ways in which capitalism expands ��� by creating, in the words of the Communist Manifesto, ���no other nexus between man and man than naked self-interest, than callous ���cash payment���.

Raising the pension age is an act of commodification in two different senses.

One is that, in compelling the older poor to work longer, it forces people to provide more of that essential commodity, labour-power. This would help bid down wages which might, under certain conditions, increase profits.

The second is that if we can only get our pension later we will have to save more via private pensions. This increases the profits of fund managers.

From this perspective, raising the pension age is a key element of neoliberalism: Colin Leys has described commodification as ���the essence of our time.��� For example, privatization and the subcontracting of public services help convert state functions into commodities, thereby expanding the realm of activities in which capitalists can make profits. The implicit subsidy to banks helps increase financialization. Restrictive copyright laws help to make money-making commodities out of basic elements of music. Companies such as Facebook are making a commodity of data. And student loans are a three-fold commodification process: in imposing debt bondage onto young people they increase future labour supply; they shift universities closer to the market sector; and they create a loan book which can be privatized and so (perhaps) offer a new source of profits for capitalists.

Much of this state-aided commodification is a response to capitalist stagnation. Much of capitalism is no longer innovative enough to create profitable opportunities endogenously: fund management, in particular, is such a rip-off that it cannot offer people value for money. Capitalism thus needs state help to expand the realm in which profitable activities can take place.

Surprisingly few on the left are aware of this process: of course, there���s hostility to outsourcing and suchlike, but this tends to be piecemeal reactions to particular events, with little realization of the bigger picture. A laudable exception to this is James Meadway, which has explicitly advocated policies such as cancelling student debt or the introduction of universal basic services (pdf) as means of decommodification.

Paradoxically, such a stance has some economic logic, especially in the case of resisting increases in the pension age. For one thing, the state is much better at managing long-run investment risk than individuals. For another, anything that makes people save more ��� such as a postponement in the state pension age ��� would tend to depress aggregate demand and profitability. And for a third, downward pressure on wages is not good for profits if consumer spending falls as well ��� something which Michal Kalecki pointed out in 1935** but which still isn���t sufficiently appreciated.

State-assisted commodification, therefore, is not necessarily a solution to the crisis of capitalist profitability (pdf) and stagnation.

* The idea that a state pension is unaffordable is also obvious horseshit. If it���s expensive for the state to provide an income in old age, it���s expensive for the private sector to do so too.

** In his essay, The Mechanism of the Business Upswing, which is behind a paywall ��� as if to prove my point.

August 16, 2019

The Peterloo paradox

From one perspective, there���s something odd about the commemorations of the 200th anniversary of the Peterloo massacre.

You can be forgiven for thinking that there should be nothing party political about these. The protestors were demanding a wider suffrage. One would expect those Tories who sanctify the ���will of the people��� to celebrate such demands. And we���d expect lovers of freedom to condemn those who killed the protestors: they were, after all, doing just what Stalin did later ��� murdering opponents of the regime.

But this is not what we see. It is trades unions and leftists who are marking the day: Mike Leigh made a film of it. Tories, on the other hand, seem much quieter.

For one thing, many Tories have never really been on the side of freedom. Of course they claimed to be in the 70s and 80s. But in many cases their protestations were insincere, merely a stick with which to beat the left. During much of the Cold War, Tories supported Pinochet, apartheid, Macarthyism, the forced labour that was national service and the criminalization of homosexuality. There were happy with repression, as long as it was they who were the repressors.

We���ve had a reminder of Tories��� attitudes to freedom recently in a report from the ���think tank��� Onward which urges the party to ���reject the freedom fighters and pursue the politics of belonging.��� Of course, not all Tories agree with this, but it reminds us that Tories��� attitudes to freedom has always been, ahem, ambivalent.

There���s something else. Peterloo was an assertion of working class agency, a refusal of workers to accept their place. Conservatives, and the ruling class in all its forms, have always been uncomfortable with this. As Corey Robin has said, the main consistent principle of conservatism has been a defence of hierarchy:

When the conservative looks upon a democratic movement from below, this���is what he sees: a terrible disturbance in the private life of power. (The Reactionary Mind, p13)

In this sense, there is a direct line from the cavalry murdering the Peterloo protestors to Arron Banks wishing Greta Thunberg dead.

Indeed, we can read Brexit as an example of the counter-revolution Corey discusses ��� a desire to reassert old hierarchies in which British rulers and bosses could exercise power unfettered by interference ��� real or imagined - from Brussels.

So perhaps there���s really no mystery after all about who���s commemorating Peterloo and who isn���t ��� because, 200 years on, many on the right haven���t changed much.

August 13, 2019

The trade deal fetish

John Bolton says the UK can strike a quick trade deal with the US. This reminds me of an under-appreciated fact ��� that it is not trade rules that are significantly holding back UK exports.

Brute facts tell us this. As part of the EU, the UK and Germany have the same trading rules. Last year, however, Germany exported $134bn of goods to the US whereas the UK exported only $65.3bn. Per head of population, Germany���s exports to the US were therefore 60% higher than the UK���s. Much the same is true for other non-EU nations. Last year Germany exported $11.8bn to Australia whilst the UK exported just $5.9bn, a per capita difference of over 50%. German exports to Canada were $12bn whilst the UK���s were $7.3bn, a 28% per capita difference. German exports to Japan, at $24.1bn were 2.2 times as great per head as the UK���s. And German exports to China, at $109.9bn were three times as great per capita as the UK���s $27.7bn.

Now, these numbers refer only to goods where Germany has a comparative advantage over the UK. But they tell us something important. Whatever else is holding back UK exports, it is not trade rules. Germany exports far more than the UK under the same rules.

As for what it is that is holding back exports, there are countless candidates ��� the same ones that help explain the UK���s relative industrial weakness: poor management; a lack of vocational training; lack of finance or entrepreneurship; the diversion of talent from manufacturing to a bloated financial sector; the legacy of an overvalued exchange rate. And so on.

If we were serious about wanting to revive UK exports, we would be discussing what to do about issues such as these. Which poses the question: why, then, does the possibility of trade deals get so much more media attention?

One reason is that the right has for decades made a consistent error ��� a form of elasticity optimism whereby they over-estimate economic flexibility and dynamism. Back in the 80s, Patrick Minford thought, mostly wrongly, that unemployed coal miners and manufacturers would swiftly find jobs elsewhere as, I dunno, astronauts or lap-dancers. The Britannia Unchained crew think, again wrongly, that deregulation will create lots of jobs. And some Brexiters in 2016 thought sterling���s fall would give a big boost to net exports.

In the same spirit, they think free trade deals will raise exports a lot. But they won't - and certainly not enough to offset the increased red tape of post-Brexit trade with the EU. Jobs and exports just aren���t as responsive to stimuli as they think. The economy is more sclerotic, more path dependent, than that.

Secondly, the BBC has a bias against emergence. It overstates the extent to which outcomes such as real wages, share prices or government borrowing are the result of deliberate policy actions and understates the extent to which they are the emergent and largely unintended result of countless less obvious choices. In this spirit, it gets too excited about trade deals and neglects the real obstacles to higher exports.

But there���s something else. Perhaps the purpose of free trade deals is not to boost exports at all. It is instead largely totemic. Such deals are one of the few things we���ll be able to do after Brexit that we couldn���t do before. They are therefore a symbol of our new-found sovereignty. They are, alas, largely just that ��� a symbol.

August 10, 2019

Tories against Thatcher

Stephen Bush expresses a widely-held opinion when he writes:

Boris Johnson sees more Thatcherites when he looks at his cabinet than Margaret Thatcher did with any of hers.

In a sense, however, this is very odd ��� because in one respect this government is fundamentally anti-Thatcherite.

What I mean is that a cornerstone of Thatcherism was the belief that a major role of government was to provide stability so that businesses could plan without having to worry about policy changes. This was the idea behind the medium-term financial strategy ��� to reduce inflation (hence creating stability) without using price or wage controls, what Nigel Lawson decried as ���ever more ad hoc interference with free markets.��� As she said:

An economy will work best when it is built on a framework of clear and predictable rules on which individuals and companies can depend when making their own plans. Government's primary economic task is to frame and enforce such rules. Its own discretionary interventions should be kept to a minimum.

In risking a no-deal Brexit this government, of course, is doing 180 degrees the opposite of this*: a course of action which requires a contingency fund to bail out the businesses it damages might be many things - some perhaps describable without expletives ��� but Thatcherite it ain't.

Johnson���s government is, of course, not alone in rejecting this fundamental Thatcherite idea. In ramping up the trade war, his ideological stablemate in the US is making ���ever more ad hoc interference with free markets��� and creating uncertainty.

And here���s the thing. Thatcher was right in this regard. We now know that policy uncertainty does indeed reduce capital spending. This is because some potential investment projects are like call options ��� firms have a choice to exercise them now or later ��� and uncertainty increases the incentive to hold onto options. Yesterday���s figures showed that business investment has flatlined for four years. One reason for this ��� of many ��� is that Brexit uncertainty has caused companies to put some projects onto the back burner. This is contributing to the stagnation in productivity and real incomes.

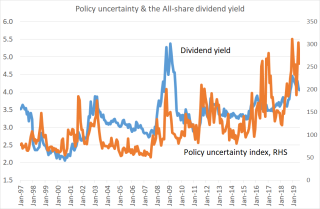

This is hurting the class that Tories are traditionally supposed to protect. My chart plots the global policy uncertainty index complied by Nick Bloom and colleagues against the All-share dividend yield. It���s clear that there���s a correlation between the two ��� of 0.55 if we���re being precise. Now, correlation isn���t causality yada yada but it���s plausible that it is to a degree. Policy uncertainty might raise the risk premium on equities, and might also reduce future growth. Both would warrant a higher dividend yield and hence lower share prices. In this sense, the Tories��� (and Trump���s) rejection of Thatcherism is hurting equity investors - who are their own class.

So, what���s going on?

One thing is that the financial crisis and decade of stagnation has shown that whilst policy stability might be necessary for economic success it is certainty not sufficient. Everybody has responded to this by doubling down on their priors. The left think it shows we need a more activist state; centrists pretend it never happened; and the right think ��� wrongly, I believe ��� that we need to escape the protectionist yoke of the EU and pursue freer trade.

But there���s something else. For one thing, this shows that the political climate does not change simply because of explicit debate about ideas. No Tory has AFAIK explicitly argued against Thatcher���s belief in the importance of stability: they just forgot it and fell into other ideas.

And for another, this tells us something about political labels. Names such as ���Thatcherite���, ���Blairite��� or ���Corbynista��� don���t merely describe a coherent explicit set of ideas. They also refer to distinct dispositions, loyalties and hostilities. Like it or not, tribalism matters.

* Some might add that Johnson's promises to jack up public spending are a rejection of Thatcherite ideas of "sound finance". Personally, I suspect that this is more defensible now that real bond yields are sharply negative.

August 8, 2019

Economics & identity

Simon says that a no-deal Brexit is pretty much in nobody���s interest and so represents a victory of the ���force of ideas rather than interests���. I largely agree, but I wonder whether the distinction between ideas and interests is so clear-cut.

To see my point, consider a different case: young people. These are more left-leaning than others: a recent Ipsos Mori poll (pdf) showed Labour leading the Tories by 34-28% among 25-34 year-olds, and that 46% of this group support either Labour or the Greens. But this is not because younger people are inherently more leftist. In the 1987 general election, the Tories actually had a big lead among 25-34 year-olds.

So, what has changed since then?

Home ownership. That���s what. In the late 80s half of 25-34 year-olds owned their own home. Now, only a quarter do. This has changed how young people vote.

But what exactly is the mechanism here? I���m not sure that it is simple mechanical self-interested support for specific policies: ���Jeremy Corbyn will cut my rent.��� This doesn���t, I think, explain the passion with which many young people support Corbyn.

Instead, what���s going on is a change of identity. In the 80s, many young people identified themselves as property-owners and voted accordingly. Today, they see themselves as propertyless and so vote Labour. There���s a reason why Thatcher was keen on home ownership. She knew that property ownership would make people more likely to identify with other owners of wealth, whilst tenancy made more likely to identify with the traditional party of the propertyless.

Perhaps an analogous thing is going on among the older wealthier people who favour no-deal. Simon is right that many of these would lose from such an outcome, not least because in hitting economic growth (both near-term and long) it would reduce interest rates and hence income from savings. But as David Leiser and Zeev Kril have shown, people are terrible and connecting the dots in economics. Just as savers don���t blame austerity for their plight, nor do they blame Brexit.

Being retired does, however, change one���s self-identity. If you no longer spend your days worrying about suppliers or customers (as many now-Brexiters did BITD) the salience of economic interests declines. This creates a gap that can be filled by nationalism.

Similarly, in an economy where productivity is stagnant, we pay less attention to growing the pie and more to preserving what we have. As Will Davies puts it:

Where productivity gains are no longer sought, the goal becomes defending private wealth and keeping it in the family. This is a logic that unites the international oligarch and the comfortable Telegraph-reading retiree in Hampshire. The mentality is one of pulling up the draw-bridge, and cashing in your chips.

It's a similar mechanism to this that helps explain Ben Friedman's point - which is perhaps the most important fact about contemporary politics - that economic stagnation breeds intolerance and closed-mindedness.

As the man said:

The mode of production of material life conditions the general process of social, political and intellectual life. It is not the consciousness of men that determines their existence, but their social existence that determines their consciousness.

In saying this, I���m sort of echoing Amartya Sen���s point ��� that we all have multiple identities. He writes:

There is a critically important need to see the role of choice in determining the cogency and relevance of particular identities (Identity and Violence, p4)

That word ���choice��� is awkward. It���s not always the case that we consciously choose our identities, Stars in their Eyes-style (���Tonight, Matthew, I���m going to be a white nationalist.���) But there is nevertheless a big element of contingency in them. Before 2016, for example, only a few of us were Leavers or Remainers.

Now, this is not to adopt a crude economic determinism. Although our identities are influenced by economic conditions they are not wholly determined by them. Marxists have pretty much always realized that class conscious is something that must be deliberately cultivated, that it does not automatically arise purely from material conditions.

The very fact that Brexit has become so salient an issue, and a shaper of identities, shows us that identities are endogenous, and malleable by political processes, not just economic ones. For me, this is one reason why the idea of politics as giving people what they want is deeply flawed. A big part of the political process lies in not just responding to people���s preferences but in shaping those preferences. Thatcher (and Lenin) both knew this, and too many of their epigones have forgotten it.

August 2, 2019

The missing backlash

Dani Rodrik asked a good question on twitter the other day: why has there been so much backlash against free trade but so little against finance?

In the UK, it���s moot whether there has been a backlash against free trade. But there certainly hasn���t been one against finance, so Dani���s question holds.

Three things make it especially puzzling.

One is that the costs of the financial crisis are vastly greater than any even half-plausible estimate of the cost of being in the EU, and yet there���s much more hostility to the latter.

A second is that scepticism about the financial sector is to some extent non-partisan. In his fine book Adam Smith: What He Thought and Why It Matters, Tory MP Jesse Norman accuses banks of ���turbo charged��� rent extraction and says: ���The banking sector may be generating little or no net real economic value.��� And there are countless small businessmen (and ex-businessmen) whose opinion of bankers would make even the hardest line Marxist blush.

And thirdly, the financial system���s rip-off doesn���t consist merely of the ���too big to fail subsidy.��� It���s also because people actually choose to be ripped off for example by buying poorly performing but high-charging actively managed funds. In its report into the industry the FCA said (pdf):

On average, both actively managed and passively managed funds did not outperform their own benchmarks after fees..when choosing between active funds investors paying higher prices for funds, on average, achieve worse performance.

So, why hasn���t there been a backlash against finance? Here are five possible non-exclusive explanations.

One is plain deference. We respect scroungers and fraudsters much more if they are rich and expensively suited than if they are poor and tracksuited. As Adam Smith said:

The great mob of mankind are the admirers and worshippers, and, what may seem more extraordinary, most frequently the disinterested admirers and worshippers, of wealth and greatness.

A second possibility is resignation. When inequality is great and entrenched, we become accustomed to it and don���t rebel.

Thirdly, we just don���t see counterfactuals. If we hadn't had the 2008 crisis we'd now have not just higher incomes but also a tolerant society without the social divisions and political crisis that Brexit has caused, But we don't see this world, We don���t therefore see so clearly the damage the financial sector has done.

This is true in another way. Even if there had been no crisis, the financial sector would still leave much to be desired. For one thing, it is exploitative and uncompetitive. As Thomas Philippon (pdf) and Guillaume Bazot (pdf) have shown, the cost of finance hasn���t changed in decades despite much technological progress. And for another, the financial sector has failed to develop useful products that might help us spread risk, such as house price futures, social care insurance or macro markets (pdf) linked to GDP, aggregate profits or occupational incomes. Because we don���t see the alternative world in which finance is competitive and offers useful innovation, we don���t realize how dysfunctional it is.

Fourthly, as David Leiser has shown, people are terrible at connecting economic facts. They just don���t link the collapse of banks with a decade of stagnant real wages. This is not helped by a media which has a bias against emergence. For example, in Jon Sopel���s interview with Gary Cohn yesterday neither party asked the extent to which the US���s economic performance might for good or ill be due to forces outside direct political control.

Which brings me to something else. For decades political debate about the economy has been framed by the presumption that capitalism is basically fundamentally healthy and that the role of the state is to provide the framework of stable policy and light regulation which frees this underlying dynamism. The question has been: how can the state serve capital? rather than: what must be done to fix or replace a rotten system? Because ideas often linger on after their factual base has withered, we are stuck in this paradigm. This is why the Tories managed to get away with describing post-crisis government deficits as the fault of Labour rather than bankers.

My point here should be a trivial one. Our perceptions of complex systems are distorted by cognitive biases. Sometimes these distortions help to legitimate inefficiency and exploitation. Behavioural economics and Marxist theories of ideology are much more compatible than is often realized.

July 31, 2019

Johnson's spending challenge

The old myth of government finances being like household ones is about to hove back into view. Johnson is promising to increase spending on the NHS, as well as on schools and higher public sector pay, as well as offering a big tax cut. To the question, ���how can he afford this?���, Tories reply:

It is because we took tough and necessary decisions to cut Labour���s borrowing after 2010 that we can afford to spend more now.

In this way, popular spending rises now can be used to defend past austerity.

Which poses the question: how can the left combat this?

It���s not good enough to say that it too favours such spending. This risks it looking like an old hipster: ���Yeh, I was into fiscal expansion before it was cool.���

Yes, we have lots of other arguments. Austerity was never necessary because there was never a danger of a sell-off in gilts; the only constraint upon government borrowing is inflation. The only ���evidence��� that high public debt was a threat to economic growth was a spreadsheet error. The cost of austerity ��� in terms of thousands of lives lost, increased poverty and despair and lower incomes ��� were horrendous.

These are all true. And irrelevant. If you don���t believe them now, you never will.

Instead, I���d suggest some other lines of attack.

One is: if the Tories are such good stewards of our money, why is sterling so weak ��� down over 7% against the euro and 15% against the US$ since 2010? This isn���t a cheap debating point. A weak pound (if sustained) is a sign of a lack of confidence in the UK���s economic prospects.

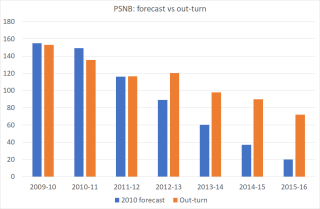

Secondly, austerity failed by its own standards. It did not reduce borrowing anything like as much as planned. For example in 2010 the OBR forecast that PSNB would be just ��20bn by 2015-16. In fact it turned out to be ��71.8bn. Over the first five years of austerity the government borrowed ��158.9bn more than expected in 2010. A big reason for this, of course, is that in depressing economic activity austerity also cut tax revenues.

Thirdly, austerity was counterproductive and unsustainable. Cutting prison staff looks like a ���saving���, until prisoners riot or re-offend upon release because of a lack of rehabilitation. ���Savings��� on flood defences prove expensive when we need to repair the damage done by flooding. Cuts in psychiatric care and youth services impose extra pressures upon the police. A lack of spending on schools isn���t a saving if parents pay a hidden tax by donating money to schools.

Aditya therefore has a point:

Every time Johnson promises some spending, Labour should retort: which are you going to believe, his press releases or the devastation you can see on your high street, at your town hall and local food bank?

I fear, though, that these replies aren���t good enough. Truth doesn���t always win in the battle of ideas. With a supine media, the Tories can get away with reversing their position on austerity when it suits them.

For me, what this shows is that there should have been, and must always be, much more to leftist economics than mere opposition to austerity and demands for higher public spending. Instead, we need policies and institutions that achieve not only greater equality of income, but of wealth and power too. The Tories might be able to match Labour for public spending, but they will never offer these.

July 28, 2019

Against adaptation

One under-rated determinant of political debate lies in the fact that we become accustomed to some things but not others.

I���m prompted to say this by reactions on Twitter to my questions about Mark ���Herr Juncker in the bunker��� Francois: how did this idiot achieve prominence? Why does the BBC think him an acceptable guest on what it considers a serious show? Why have our selection mechanisms & standards gone so badly awry?

Some replied that the BBC is chasing click bait, or that it is human nature for people to cheer on those on their own side, regardless of their competence.

What such replies miss, however, is that these phenomena are more prominent now than they used to be. I might be guilty of selective memory or golden age mythologizing, but I don���t recall John Tusa interviewing as many performing baboons on Newsnight in the 80s as Emily Maitlis does now. Of course, many MPs in the past were buffoons or wrong ���uns, but they rarely achieved great prominence and if they did get into government they were usually found out, and if sacked in disgrace they did not often return swiftly to government as Patel and Williamson have. The prominence of low-grade MPs is relatively new. We should not take it for granted, but ask how it happened.

Equally, the BBC���s non-existent editorial standards ��� which allow it to uncritically report Trump���s obvious nonsense about a UK-US trade deal could lead to a "three to four, five times" increase in trade ��� should not be taken as normal.

These, however, are not the only examples of what I mean, or even the best ones. There are others:

- We think it natural that young people should be left-wing and so support Corbyn. This is not so. In the 80s, the Tories won more votes from under-35s than Labour did. The much-caricatured yuppies were Tories, not hard leftists (except me).

- We���ve become accustomed to think the main dividing line in politics is between Leavers and Remainers, leading to talk of post-party politics. But in fact, the words ���Leaver��� and ���Brexiter��� meant nothing just four years ago, when only a handful of cranks were obsessed with the EU: less than 10% of voters thought it the most important issue before 2016. And when the Tories let themselves get obsessed with Europe in the 90s, they were obliterated in general elections (Blairites might have a theory as to why).

- Many people have resigned themselves to the fact that austerity cost us more than 10% of GDP and many lives. The Lib Dems can therefore plausibly ask us to move on from austerity and fight Brexit instead. The potential cost of Brexit is seen as much nastier than the cost of austerity, even though it is probably smaller.

- People adapt to inequality: as it rises, so too do our ideas of what level of inequality is acceptable. In this way, we resign ourselves to it.

What���s going on in these cases are specific instances of a widespread phenomenon: adaptation. We get used to most hardships and even to the most abject poverty. Often our mental health and even our survival require us to do so. But this comes at a price ��� that we accept the unacceptable. As the old saying goes, it is easier to ask forgiveness than permission (which seems to be the nearest Lib Dems have to a political philosophy).

This generates a status quo bias ��� a tolerance of big existing evils but resistance to even small threats. Those who expect us to get over austerity want us to think that the possibility that Corbyn���s tax rises will slightly shrink GDP is intolerable.

Oppressors everywhere have exploited this. Generations of us sang that ���He made them high and lowly, and ordered their estate.��� Misogynists pretend that gender roles are natural and not social constructs. Right-libertarians want us to think that capitalism is natural whereas in fact it is the product of coercion; it came into the world ���dripping from head to toe, from every pore, with blood and dirt.��� Racists have always looked for some "natural" inferiority in black people. And escapees from North Korea are often surprised by the wealth of the west because they've been indoctrinated to think abject poverty is widespread and normal.

We must of course resist all this. Socio-political structures and beliefs are not natural and inevitable but are instead products of human action if not design. We should therefore resist what Trotsky called kowtowing before accomplished fact. Instead, we must ask: how do some issues come to dominate bourgeois Westminster politics whilst others are off the agenda? How are political identities shaped so that cultural ones (Leave/Remain) efface class? Why has capitalism changed in the last 30 years to alienate young people? Why are selection mechanisms in politics and the media now less effective at filtering out idiots and charlatans? How did the BBC come to be infected with crass consumer culture to the detriment of public service broadcasting? And so on.

If we think of politics merely as our tribe against theirs, we ignore such questions. And guess whose interests this serves?

Chris Dillow's Blog

- Chris Dillow's profile

- 2 followers