Chris Dillow's Blog, page 54

September 20, 2017

The harm of high housing costs

The Resolution Foundation points out that people are spending three times as much of their incomes on housing today than they were 50 years ago, and that 30-year-olds spend more of their income on housing than did their grandparents at the same age.

You can see this as an inter-generational injustice. But there���s another question here: are high house prices bad for the economy generally? I suspect they might be, for several reasons:

First, sharply rising house prices are associated with increasing household debt, which increases the chance of a financial crisis which has long-lasting adverse effects upon growth. As Mian, Sufi and Verner conclude (pdf):

An increase in the household debt to GDP ratio predicts a subsequent reversal in debt and lower subsequent GDP growth. The predictive power is large in magnitude and robust across time and space.

Secondly, housing is prone to the Baumol disease. Because the housing sector has lower productivity growth than other sectors, a shift in spending towards it tends to reduce overall productivity growth. To put this another way, if younger people weren���t spending so much on rent, they could spend more on other things, which would stimulate output, innovation and entrepreneurship in more dynamic sectors.

Thirdly, years of rising house prices have encouraged a culture of investment in bricks and mortar. This has diverted potential entrepreneurs into ���property development��� and away from perhaps more socially useful activity; has encouraged people to regard their house as their pension and so diverted capital away from business investment and formation; and might have encouraged early retirement and a loss of skilled labour*.

Fourthly, high house prices give people an incentive to protect their investments, and this breeds the sort of nimbyism which can delay infrastructure investment.

Fifthly, high housing costs encourage people to commute long distances. Not only is this bad for their well-being, but it can also depress their productivity.

I���ll grant that there are some offsetting considerations. In the past, high house prices have been a source of collateral for entrepreneurs; thousands of people have taken out second mortgages to start businesses they���d otherwise be unable to. However, with so many energetic young people now locked out of home ownership, high house prices are perhaps less likely to stimulate entrepreneurship in the future.

Also, you might argue that it���s not wholly a bad thing that people are forced to rent. Andrew Oswald has shown that high home ownership impedes labour mobility and so raises frictional unemployment. I���m not sure how relevant this is, though. Big differences in rental costs across the country can also reduce mobility: many people can���t afford to move to London, even if they were stupid enough to want to.

My point here is that we shouldn���t simply be asking whether high housing costs are an unjust burden on young people. We should also consider the possibility that they damage the whole country���s economic prospects. Slower long-term growth means there���ll be less to spend on (among other things) the NHS, so even those of us who have benefited from high house prices up to now might suffer in future. Torsten Bell might well therefore be right to speak of a ���housing disaster���.

* I���ll be retiring early thanks to the house price boom of 1994-2008 ��� not that it���ll be a loss.

September 19, 2017

Corbyn's success: centrists' failure

For months the Times has been running a series of columns on how centrists are befuddled by Corbynism. Nick Cohen improves upon those pieces.

His piece contains a big truth ��� that Corbyn ���won the left-behind middle class.��� Not only are Labour members disproportionately professionals, but also Corbyn���s Labour polled well among the AB social group.

This happened in large part because, as Rick said, the middle-class isn���t as posh as it used to be. Younger professionals especially have become proletarianized. They have high debt, no hope of buying a house and stressful and oppressive working conditions.

In this context, calling Corbynistas middle class is to look at class the wrong way ��� as a social gradient rather than a property relation. A lot of Corbyn���s support derives from the propertyless ��� those who are the victims of capitalist stagnation and oppression and not its beneficiaries. As Nick says, it comes from people "unable to meet the basic middle-class membership requirement: the ability to buy a home."

This poses the question: if Corbyn is as deplorable as Nick thinks, why are so many decent intelligent people supporting him so enthusiastically?

It���s not because they are fucking fools. It���s because centrists contributed to the economic trends which have given us cheesed-off professionals, and those people are embracing Corbyn as an alternative to the policies that have failed them so badly. Centrism did so in several ways:

- New Labour���s endorsement of managerialism has created a proletarianized professional cadre who lack autonomy at work ��� and this managerialism might also have contributed to the stagnation in productivity that has given us a decade of flat real wages. (To his credit, Nick has attacked this trend; he just hasn���t connected it to the popularity of Corbyn).

- In acquiescing in the increased income, wealth and power of the 1%, centrists tolerated inequality between the ultra-rich and ���middle class��� sorts in the 10th-20th percentiles. As Tim says, this bred a resentment among the latter. (Personally, I think the resentment justified, but that���s by-the-by).

- Centrists have offered little solution to the unaffordability of housing, which has given us a propertyless ���middle class���.

- The Lib Dems��� acquiescence in austerity, and the Labour right���s failed attempt to triangulate it, meant that centrists are associated with the squeeze on living standards, especially in the public sector. They are, of course, also responsible for high student debt.

Moralizing about Corbyn misses the point ��� that his support has definite economic roots in stagnation; the pulling away of the 1% (or 0.1%) from other professionals; the rise of immaterial labour; unaffordable house prices; and degradation of erstwhile good jobs. It also misses the point that centrists contributed to these trends, or at least acquiesced in them. Support for Corbyn is a reaction against all this.

Worse still, attacks upon Corbyn distract liberal centre-leftists from what should be their biggest job ��� of redefining centrism to make it appeal again. It���s difficult to sell capitalism to people who have no capital and little hope of getting it. Until centrists grasp this fact and correct the errors that led us to this mess, Corbyn might well remain popular, for all his faults.

Update: on re-reading Nick's piece, I realize I was too harsh on him, and have tweaked this accordingly.

September 14, 2017

UK vs US capitalism

Frances Coppola says that in developed economies:

Wages have not kept pace with productivity for the whole of the 21st century. Workers' wages simply don't reflect their marginal productivity any more.

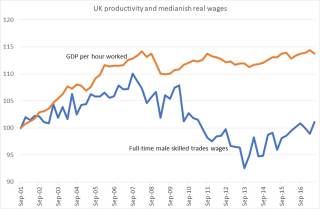

However, this is perhaps not so true in the UK as it is in the US. My first chart compares the real wages of full-time men in skilled trades (which I'm using as a proxy for median wages)* to labour productivity. This shows that since data began in 2001 real wages have indeed lagged behind productivity.

However, most of the gap is because real wages fell between 2008 and 2013. Since then, wages have actually risen faster than productivity.

I suspect the story here is that sterling���s fall in 2008 cut real UK incomes, and wages suffered from this.

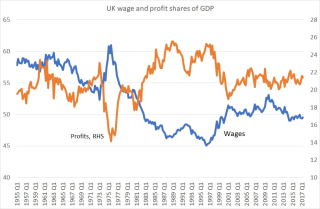

My second chart is consistent with this. It shows that the shares of wages and profits in GDP haven���t budged much over the last 20 years. Although the share of wages in GDP fell after 2009, this only reversed a rise in the mid-00s. The wage share is now much the same as it was in the late 90s.

This is a marked contrast to the US, where the wage share has fallen this century.

The difference, I suspect, lies in the fact that monopoly power has risen in the US but not in the UK. The US has seen a rise in ���superstar firms��� (pdf) in recent years whereas the UK has not: there���s no UK equivalent of Apple or Microsoft. Yes, I know, some people quibble with this. But the evidence for it doesn���t lie only in academic studies. It���s also in the stock market. In recent years, the US market has out-performed the UK. One reason for this might well be that investors have been attracted to US companies which offer what Warren Buffett calls economic moats ��� things that allow firms to fend off competition.

In saying this, I���m not denying that UK workers are exploited; they are (pdf). Nor am I disputing Frances��� dismissal of marginal productivity theory. My point is simply that, right now, there is a difference between UK and US capitalism. Whereas US capitalism is a story of increasing monopoly, the UK story is more one of stagnation.

* Average wages might be distorted by changes in very high wages. There is also annual data on median wages from the ASHE, but these contain a few breaks in the series, although they show a similar picture to my chart.

September 11, 2017

Economic roots of post-truth politics

Here���s a conjecture: the rise of ���post-truth��� politics (defined by the OED as a process whereby ���objective facts are less influential in shaping public opinion than emotional appeals���) is in part the product of deindustrialization.

What I mean is that in manufacturing, facts defeat emotions and opinions. If your steel cracks, or your bottles leak or your cars won���t start, all your hopes and fancy beliefs are wrong. Truth trumps opinion.

Contrast this with sales occupations. In these, opinion beats facts. If customers think a shit sandwich is great food, it���ll sell regardless of facts. And conversely, good products won���t sell if customers think they���re rubbish. Opinion trumps truth.

(Finance is a mix of these. In trading and asset management, beliefs are constantly defeated by cold hard facts. In asset gathering, sales and investor relations, however, bullshit works.)

Isn���t it therefore possible that a shift from manufacturing to other occupations will contribute to a decline in respect for facts and greater respect for opinions, however ill-founded? In 1966 ��� when employment in UK manufacturing peaked ��� 29.2% of the workforce were in manufacturing. This meant that millions more heard tales from fathers, husbands and friends about how brute facts had fouled up their day. A culture of respect for facts was thus inculcated. Today, however, only 7.8% of the workforce is in manufacturing and many more are in bullshit jobs. This is an environment less conducive to a deference to facts.

How people live shapes how they think. A world in which many people work in manufacturing might, therefore, have different beliefs to one in which they don���t.

You might object here that the UK has been deindustrializing since the 60s, so why should ���post-truth��� only have emerged so recently?

In part, it didn���t. Lies are as old as politics. Saatchi and Saatchi���s famous 1979 poster ���Labour isn���t Working��� was a picture not of jobless workers but of Tory party volunteers. And Kelvin Mackenzie���s Sun did in the 80s pretty much what Breitbart does now.

Also, culture can persist long after the economic circumstances which created it fade away.

And also, it is only recently that the technologies have emerged to facilitate a post-truth media. Breitbart or the Canary probably could not have emerged in a time when you needed to spend millions on printing presses and when the established press had strong brand loyalty.

So far, so much conjecture. What sort of facts would support or disconfirm this?

I can think of two supportive facts. One is that post-truth politics seems (I might be wrong) to be less strong in countries where manufacturing still looms large in culture if not in economics, such as in Germany or Japan.

The other is that pre-industrial societies tend to have less scientific cultures than industrial ones. For example, in 17th century England people believed some very strange things. It���s a commonplace that the Industrial Revolution grew from the scientific revolution and Enlightenment. But mightn���t the causality run both ways? Maybe the Industrial Revolution strengthened respect for facts and evidence, a respect that���s declining in our post-industrial age.

Now, I stress all this is just a theory. Feel free to offer some discorroborative evidence. But it has a worrying implication. What I���m saying implies that post-truth politics isn���t just a bad thing done by bad people and followed by silly ones. It might instead have a strong economic root and those who deny this and consider it merely a moral failing are guilty of what Phil calls structural naivete. If so, then we might be stuck with post-truth politics for a long time.

September 9, 2017

Immigrants as scapegoats

People who care about things like evidence and prosperity have pointed out that proposals to limit EU immigration after Brexit are bad for the economy. It���s not sufficient, however, merely to point out facts. We must also ask: why ��� of all the false beliefs it is possible to have about the economy ��� is the idea that migrants significantly depress wages so widespread and entrenched?

In some cases, of course, it���s simply a rationalization of hostility to migrants. Some people would hate immigrants whoever they were and whatever they did. The claim they do economic damage is a cloak for such feelings.

There are, though, more respectable motives. I don���t think it's unreasonable to feel a little uncomfortable about high migration on the grounds that it might disrupt our sense of home or that diversity might in the long-run undermine social solidarity and hence perhaps (pdf) support (pdf) for redistribution; it���s an awkward fact for leftists that several egalitarian nations (such as the Nordics, Japan and South Korea) tend to be more ethnically homogenous than less egalitarian ones such as the US*. It���s easy for such people to commit a form of halo effect, and fear that because migration might be bad in some senses it is also bad in others.

Nor must we overlook folk economics. Very many people can tell stories along the lines of ���since a lot of Poles arrived my wages have fallen.��� And these have a simplistic appeal: increased supply means lower prices, doesn���t it?

To counter these stories we need not just a technocratic appeal to the facts but to point to mechanisms which offset those stories ��� such as that immigration also increases demand. People are bad at making connections about the economy. They must be shown how to do so, but there are no institutions which do this.

I���m not sure, though, that these explain the Tories��� urge to blame migrants for stagnant real wages, and they certainly don���t justify Ms May���s refusal to even consider evidence about the matter.

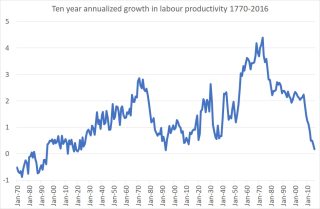

Instead, I suspect something else is going on. The Big Fact about the economy is that we���re now seeing the weakest trend productivity growth since the early days of the industrial revolution; it���s this that is largely responsible for flat real wages. Any non-risible political party must have some sort of analysis of this.

The Tories, however, not only do not but cannot offer such an analysis. Obviously, they cannot blame austerity. Nor can they blame trades unions or red tape, as they did in the 1980s. And nor can they blame capitalist stagnation or managerialism. This leaves immigrants as pretty much the only possible scapegoat.

I���ve said many times that capitalist stagnation fuels hostility to immigration. The Tories exacerbate this because their political and intellectual limitations mean they cannot do anything else but blame immigrants for stagnant real wages. In this sense, curbs on immigration have something in common with Jacob Rees-Mogg (Roderick Spode masquerading as Gussie Fink-Nottle) being considered a half-credible leadership contender: both are signs of a deep intellectual and political malaise in the party.

* My sympathy for open borders ��� like my anti-managerialism ��� perhaps owes at least as much to my Hayekian as my Marxian influences.

August 30, 2017

Against high CEO pay

Imagine we lived in a feudal society in which lords exploited peasants. A defender of the system might argue that wealthy lords perform a useful service; they protect their peasants from invasion and theft thus giving them security and a little prosperity. And competition between lords should improve these services; bad lords will find their lands and peasants seized by better lords who become wealthier as a result.

Such an argument would, however, miss the point. The case against feudalism is that the system as a whole is unjust and inefficient. The fact that good lords provide services and are richer than bad ones is quite compatible with this.

This analogy came to mind whilst reading Ben Ramanauskas���s defence of high CEO pay. The fact that good CEOs make a positive difference to a company does not in itself justify a system in which CEOs in aggregate ��� many of whom are far from good ��� get fortunes.

Two big facts suggest that such a system might well be inefficient.

One comes from Rene Stulz and Kathleen Kahle. They point out that there are now fewer stock market-listed companies than there were years ago, and most are less profitable than they were. This alerts us to the possibility that agency failures ��� the inability of shareholders to oversee managers ��� are damaging.

The second, bigger, fact is that as CEO pay has risen, productivity growth has fallen. This is consistent with the possibility that increased inequality between bosses and workers is . We have many theories as to why this might be. Inequality reduces trust, which is necessary for growth. High pay crowds out intrinsic motivations (pdf) and causes managers to focus (pdf) upon things that are monitorable (such as short-term earnings) rather than ones that are not, such as longer-term investments and innovations. Hierarchical systems lead to bad decisions because bosses lack complete information, and can demotivate junior staff. And high CEO pay encourages juniors to engage in office politics to seek promotion, and incentivize managers to strengthen their position by discouraging disruptive innovation and entrenching monopoly power.

But what of the argument that competition eventually eliminates bad bosses? True, it does sometimes; the relatively egalitarian John Lewis Partnership has done better than department stores such as House of Fraser or Debenhams, for example. But market forces are weak (and perhaps getting weaker).

One reason for this is simply state intervention; without this, almost all shareholder-owned banks with their high-paid CEOs would have vanished.

Another reason is that there isn���t really a properly-functioning market for CEOs. I own tens of thousands of pounds of shares, but I���ve never been asked to vote on a CEO���s pay. Instead, the vote is exercised by fund managers many of whom are more bothered by the relative performance of their funds than absolute performance. We have widespread agency failures in which mates pay each other. And as Milton Friedman said:

If I spend somebody else���s money on somebody else, I���m not concerned about how much it is, and I���m not concerned about what I get.

Unsurprisingly, then, there is little clear link between CEO pay (pdf) and corporate performance. It might be that high pay is better explained by rent-seeking than as a reward for maximizing shareholder value - though as it's almost impossible to know in most cases what constitutes maximal value, we might never know for sure.

In fact, my analogy with feudal lords is too generous to CEOs. Whereas (arguendo) a bad lord would pay for his incompetence perhaps with his life, bad CEOs walk away with fat pay cheques.

When so-called free marketeers try to defend bosses��� pay, they do the cause of free markets a huge dis-service by encouraging people to equate free markets with what is in effect a rigged system whereby bosses enrich themselves with no obvious benefit to the rest of us.

August 28, 2017

On models & downs

Simon has a nice post on the contrast between economic models which are theoretically coherent but empirically weak, such as microfounded DSGE models, and empirically stronger but theoretically weak models such as VARs. This poses the question: why do we need both?

To see why, think about American football. A team has four attempts (���downs���) to advance ten yards. If it doesn���t do so, its opponents gain possession. Many teams therefore often punt the ball downfield on the fourth down, so that they concede possession as far from their goal as possible.

How would an economist model this behaviour?

We could do so in atheoretical statistical terms, by simply regressing the probability of a team punting upon a few variables: distance from goals, yardage needed, quality of running backs and so on. This should yield decent predictions.

But what if the rules were to be changed one season, so a team were allowed six downs before conceding possession? Teams would then be much less likely to punt, and more likely to try to win yardage by running or passing. Our atheoretical model would fail. But a microfounded model based upon teams trying to rationally maximize expected points would probably do better.

My analogy is not original. It���s exactly the one Thomas Sargent used (pdf) back in 1980 to argue for what we now call microfounded models. Such models, he said, allow us to better predict the effect of changes in policy:

The systematic behavior of private agents and the random behavior of market outcomes both will change whenever agents' constraints change, as when government policy or other parts of the environment change. To make reliable statements about policy interventions, we need dynamic models and econometric procedures which are consistent with this general presumption.

The question is: how widely applicable is Sargent���s metaphor?

I suspect it is in many contexts, not least of which is regulatory behaviour. It implies, for example, that simple regulations requiring banks to hold more capital will lead not necessarily to safer banks but to them shovelling risk into off-balance sheet vehicles.

I���m not so sure, however, about its applicability to macroeconomic policy, in part simply because people have better things to do than pay attention to policy changes. For example, the Thatcher government in 1980 announced targets for monetary growth which, it hoped, would lead to lower inflation expectations and hence to lower actual inflation without a great loss of output. In fact, output slumped, perhaps in part because inflation expectations didn���t fall as the government hoped. And more recently, households��� inflation expectations have been formed more by a rule of thumb (���inflation will be the same as it has been, adjusted up if it���s been low and down if high���) than by the inflation target.

This is not to say that the Sargent metaphor (and Lucas critique) are always irrelevant. They might well be useful in analysing big changes to policy. The question is: what counts as big?

My point here is the one Dani Rodrik has made. The right model is a matter of horses for courses. Atheoretical statistical relationships serve us well most of the time. But common sense tells us they will sometimes fail us. Our problem is to know when that ���sometimes��� is.

This is not to say that the microfounded model must always be one based upon rational utility maximization; it could instead be one in which agents use rules of thumb.

In fact, Sargent���s metaphor tells us this. David Romer has shown (pdf) that football teams��� behaviour on the fourth down ���departs from the behavior that would maximize their chances of winning in a way that is highly systematic, clear-cut, and statistically significant.��� There���s much more to microfoundations than simple ideas of rational maximization.

August 25, 2017

In defence of Laura Pidcock

Laura Pidcock���s claim that she has ���absolutely no intention of being friends��� with Tories because they are ���the enemy��� raises the question of whether tribalism in politics is a good thing. I suspect that, for her, it is.

This seems an odd thing to say. I don���t want politics to consist of a set of echo chambers in which people only talk to the like-minded, and I like to think this blog sometimes tries to speak to non-leftists. ���My side right or wrong��� has given us the ugly spectacle of some leftists supporting dictatorial or failed statist policies, and of supposed libertarians making common cause with fascists even though their philosophies should in principle be miles apart*.

On the other hand, though, there are some things to be said for tribalism.

First, it can be a useful cognitive short-cut. We all lack the knowledge and rationality to make good decisions, except in a very few spheres. Using others as a guide can therefore be what Gerd Gigerenzer calls a ���fast and frugal heuristic���. For example, in 2010 I defended tribalism on the grounds that:

In being averse to having an Etonian as PM, I am taking a quick route to the judgment that such a man will take decisions about unknowable future events that I mightn't like.

Subsequent events have not discorroborated that view. Likewise, the fact that Brexit was supported by a bunch of cunts should have been a clue that it wasn���t a good idea**. Being on the opposite side of Farage is generally a comfortable position.

You might object that this isn���t always the case and that leftists have something to learn from Tories. There���s a little truth in this. Lefties should learn from Oakeshott, Burke and Hayek that individual wisdom and knowledge is bounded and that there is therefore something to be said for both markets (or decentralized decision-making) and tradition. And we should listen to thoughtful Tories such (pdf) as Jesse Norman.

But these are exceptions. The fact that the Tory manifesto was devoid of ideas tells us that the statist wing of the party has nothing useful to say, whilst the free market wing seems to consist of boilerplate Econ 101 which hasn���t progressed since Hayek (and what it learnt from him was wrong). And all sides have had their minds addled by Brexit. For the most part, Ms Pidcock isn���t missing anything by avoiding Tories.

She is also to be applauded for recognizing that politics is not a cosy game in which, after lively debate, jolly good chaps retire to the bar to have a laugh. It is instead a matter, literally, of life and death: Tory benefit cuts have driven people to suicide, and their threat to deport foreigners has caused genuine distress and uncertainty. In these senses, Ms Pidcock is right to call them the enemy. We live in a class-divided society in which the political question is ultimately Pete Seeger's (or Billy Bragg's): which side are you on?

There���s something else. There has always been a danger that Labour MPs would be seduced by the glamour and wealth of the people they meet in parliament: not just Tory MPs but lobbyists and businessmen. This is one of many ways in which their radicalism can be dissipated. It���s why the ending of Orwell���s Animal Farm has such force for the left:

The creatures outside looked from pig to man, and from man to pig, and from pig to man again; but already it was impossible to say which was which.

Ms Pidcock is awake to this danger. For that, I applaud her.

* Such an alliance, however, makes sense if you regard right libertarianism not as a coherent philosophy but merely as the voice of over-entitled white men. As a friend of mine said, ���we���re all Robert Nozick on a bad day.���

** I���m not of course saying that all Brexiters are cunts.

August 24, 2017

The weather/climate bias

Ben and Simon complain about the BBC���s unbalanced coverage of Patrick Minford���s Brexit fantasies. I sympathize. I suspect this was due to the BBC being so desperate to avoid the allegation of being biased against Brexit that it toppled over too far the other way. Such an error is in theory easily remediable.

I fear, though, that there might be a more insidious bias at the BBC, which arises from the very nature of news itself ��� a tendency to report the weather rather than the climate.

What I mean is that economic ���news��� consists of reports of high-frequency events: changes in share prices, inflation, unemployment and so on. What this ignores are slower moving changes which are in fact of much greater significance, such as: the decade-long stagnation in productivity and GDP per head; the slowdown in world trade; job (pdf) polarization; the combination of savings glut, shortage of safe assets and slowdown in capital spending that have led to negative long-term real interest rates; and the flat Phillips curve which signals that workers lack (pdf) bargaining power.

Under-reporting of these developments is not merely an intellectual error which creates a bias against understanding. It leads to systematic distortions. One is a failure to appreciate the extent to which the economy is failing ordinary working people. The other is excessive sympathy towards fiscal austerity, the case for which is gravely undermined by stagnant demand and negative real interest rates.

These biases are exacerbated by three others. One, as Jon Snow has said, is that senior broadcasters are out of touch with ���ordinary��� people. They don���t therefore understand the extent to which a few pounds make a huge difference to material and mental well-being, and so under-appreciate the importance of slow-moving developments which trap people into low incomes.

A second is a failure to make connections. People are generally bad at linking economic events. In particular, journalists have under-appreciated the tendency for economic stagnation to foster intolerance. The economic climate influences the political climate. In not making this connection, the importance of economics is under-rated.

A third is what I���ve called a bias against emergence. Journalists like human interest stories ��� somebody to praise or blame. But the developments I���m thinking of aren't such stories. No single person is to blame for stagnation, negative rates and job polarization. They are complex stories. Reporting them doesn���t fit the standard template of what constitutes journalism.

My point here is a simple one. Media bias isn���t simply due to reporters being incompetent or right-wing gits ��� though some are. It can also arise unintentionally.

August 23, 2017

A new capital?

What does capital do in the digital economy? This is the question posed by Phil in an important post. He says:

Capital is proving itself surplus to the requirements of social production and is therefore assuming ever more parasitical, rentier forms���How long can these parasitic relations last? When will Uber drivers call time on the very visible deductions made from their fares and replace the app with a cooperative effort? Is the time coming when Silicon Valley can no longer ponce off ad revenues generated from other people's content?

I certainly agree that a feature of modern capital is parasitism. Perhaps the most egregious examples of this are not so much social media firms using the free content provided by its users to generate ad revenue for themselves but the way in which bookies and doorstep lenders (the latter with mixed success) use their low cost of capital to exploit the desperate.

However, I���m not so sure that labour can yet be as autonomous as Phil claims.

Compare my job to the classic old-style industrial capitalist. The latter not only provided machinery and working capital but also in many cases the production process itself, as he had invented it. The IC gives me none of these things. I have all the physical capital I need at home. All the IC provides is a content management system which sometimes works.

But this does not mean the IC has little power over me. What it has is brand power. This allows it to extract money from readers, some of which comes to me. Its brand allows me to monetize my work in a way I can���t so easily do from blogging. From my point of view, the IC is a reliable and efficient alternative to Patreon. To get access to this, I must perform some mildly oppressive, exploited and alienating work.

Much the same is true for other immaterial workers. Working for a top accounting, law or advertising firm gives you a means of monetizing skills that are otherwise harder to monetize. (Not impossible, because workers do leave to set up on their own account. But the fact that many don't tells us that they are bound to the brand.)

A similar thing answers Phil���s question: why don���t Uber drivers leave to join a coop?

Some do. But there���s a big barrier here. Uber has a brand presence which links cabbies to millions of potential customers. Potential rivals lack this. And as David Evans and Richard Schmalensee show, it���s hugely expensive and risky to create good platform businesses: you suffer massive costs before getting the platform to sufficient critical mass ��� with people on both sell and buy sides ��� to be viable.

The fact that labour is immaterial is only part of the story of the new economy. Capital has become immaterial too. Intangible capital such as brand power ties us to capitalism. I need the IC���s brand to make a living, just as my ancestors needed cotton gins.

Perhaps, therefore, the shift to immaterial labour (insofar as it is happening) doesn���t much increase the autonomy of workers. Yes, the glue that binds us to capital has changed, but the social relationship is similar.

There���s a paradox here, and a question.

The paradox is that one early hope for the internet was that it would cut out the middleman by removing the information advantage he traditionally had. And yet it has enabled capital to become the middleman in more ways. The power of Uber, Facebook and brands generally come from being middlemen between workers and customers or writers and readers.

The question is: is intangible capital a social good or just a private one? Traditional machines are a social good; they increase aggregate output. But this is not so true of intangible capital. Coca-Cola���s brand is certainly an asset for Coca-Cola shareholders (and workers). But it���s a liability for Pepsi. Likewise, Uber���s brand is a barrier to entry for rivals. It���s what Warren Buffett calls an economic moat: it increases Uber���s value, but at the expense of making the economy less competitive. In this sense, perhaps Phil is very right: the new capitalism is parasitic.

It might be no accident that the growing importance of intangible capital has led to increased monopoly and less competition (in the US if not elsewhere) and hence to a strong stock market but weak economy and stagnant wages for most workers.

It might, therefore, be that capitalist stagnation and the shift to immaterial labour are related.

Another thing: Phil draws upon the work (pdf) of Hardt and Negri, but I suspect it can be translated into bourgeois social science. Years ago, Luigi Zingales was pondering (pdf) what the new economy and growing importance of human capital meant for the nature of the firm, for example.

Chris Dillow's Blog

- Chris Dillow's profile

- 2 followers