Chris Dillow's Blog, page 58

July 9, 2017

The crisis of positive-sum capitalism

Is capitalism a positive-sum or zero-sum game? The answer is: both: Smith and Marx both had a point. However, the extent to which it is either varies from time to time.

For example, from the mid-40s to the mid-70s, high wage growth and full employment were in capitalists��� interests. Rising wages sustained aggregate demand not only via consumer spending growth, but also because higher wages gave firms incentives to invest in labour-saving technology.

In the 70s, though, this ceased to be the case. Wage growth then began to squeeze capitalists��� profits. The positive-sum game became a zero-sum one, as Marglin and Bhaduri have described.

The solution to this was Thatcherism, or if you prefer neoliberalism. Policies aimed at restoring profit margins by weakening trades unions and the welfare state and creating job insecurity helped to raise productivity, profit rates and growth.

But we might now be back in a phase of a positive-sum game. A recent paper by Servaas Storm argues that secular stagnation is due in large part to ���the deliberate creation after 1980, through economic policies, of a structurally low-wage-growth economy.��� Low wages, and low wage growth deter firms from investing in new technology, and thus causes low productivity growth. This echoes a point recently made by Ben Chu, and is consistent with the fact that the neoliberal era has seen falling productivity growth.

In this sense, low wages aren���t just bad for workers, but for capitalists too ��� because low productivity means falling profit rates (pdf) and low real interest rates and hence low returns on savings. Of course, low wages are good are any individual capitalist. But they are not necessarily good for all.

In this sense, Tories today might be in a similar position to social democrats in the 70s. Back then, Labour was playing a positive-sum game in a zero-sum economy. The result was both an economic crisis and intellectual disarray in the party from which it took years to recover. Today���s Tories are playing a zero-sum game in a positive-sum world, and the results are similar: economic crisis and intellectual confusion.

But there���s another parallel with then. Thatcher���s project of shifting us from positive-sum to zero-sum policies was a dangerous and uncertain one. The same might be true of the shift back. Not all policies to increase wages would necessarily be beneficial. As Servaas says, a general wage rise is not a magic bullet. I have three problems here:

- One reason why higher minimum wages haven���t so far had much adverse effect upon employment is that they have diminished employers��� monopsony power. There���ll come a time, though, when this low-hanging fruit will have been plucked, and so further rises in minimum wage would hurt jobs. Seattle at least might be around this point.

- Many low-wage industries are also low-profit industries; think of hand car-washes or care homes. Higher wages in such industries might not stimulate innovation so much as just close them down.

- With savings low and debt high, households might respond to higher wages by saving more. If so, we���ll not get higher aggregate demand and hence incentives to invest. There���s a warning here from the 70s. One reason why the positive-sum game broke down then was that workers saved increasing proportions of their wages.

These doubts don���t make me side with neoliberalism. They just make me think that wage-led growth is nothing like sufficient.

July 6, 2017

Experience matters

There might be a link between the age gap in British politics and the recent sell-off in bond markets.

I���m thinking of here of some work by Ulrike Malmendier. She���s shown that experiences in our formative years influence our behaviour years afterwards. For example, investors who experienced recessions in their youth are less likely (pdf) to hold equities than otherwise similar people who didn���t, and company bosses (pdf) who experienced such recessions are less likely to use external finance.

Her work chimes with me. I���ve always been risk averse, perhaps because of circumstances I experienced in my youth.

Recent experiments by Pieran Jiao at Nuffield College Oxford have corroborated this. He gave some subjects a long position in shares and others a short position, and then showed them the share price moves, so that some saw profits and others losses. He then asked subjects to predict subsequent price moves. He found that those with long positions who had made a profit predicted higher future prices than others. Conversely, those with short positions who had made profits predicted further price declines.

All this suggests that direct experience of something slightly distorts our future expectations. Experience of profits makes us optimistic, whilst experience of recessions makes us gloomy. This fits with David Hume���s distinction between impressions ��� our ���more lively��� sensations induced by direct experience ��� and ideas which are ���less lively.��� Impressions impact our expectations more than mere ideas.

Which brings me to the bond sell-off. Older traders remember the ���bond massacre��� of 1994, when a widely-expected Fed tightening triggered a slump in the market. And they have a mental image that ���normal��� interest rates are much higher than they are now ��� because what���s normal is what we experienced in our impressionable years. These impressions make them jumpy when central bankers talk, however Delphicly, about normalizing monetary policy.

In fact, these being financial markets, it���s not necessary for traders to actually possess such impressions themselves. If they fear that others have such impressions ��� or fear that others will fear that others might have them and so on ��� that is enough for the prospect of normalization to cause a bond sell-off.

A similar mechanism might explain oldsters' greater antipathy to Labour. Jeremy Corbyn���s links with the IRA look awful to many people old enough to remember the Birmingham pub bombings, but they don���t mean much to voters who weren���t even of school age when the Good Friday agreement was signed. And Tory attempts to scare voters with talk of Labour���s fiscal incontinence resonate with those who remember Britain ���going cap in hand to the IMF���, and who regard high borrowing costs as normal. But they just elicit a shrug to people with no such memories.

Even for the most historically aware of young voters, the Troubles and the IMF crisis are ��� in Hume���s words ��� faint ideas rather than the lively impressions they are to oldsters. That���s a significant difference.

Perhaps, therefore, there are genuine lasting differences between different age groups. And these arise in part because our beliefs are shaped not just by current reality but also, partly arbitrarily, by the past.

July 5, 2017

Money tree economics

Richard Murphy says we can afford to give public sector workers a pay rise. I think I agree, for a reason he doesn���t mention.

It���s trivially obvious that Theresa May was wrong to claim that there���s no magic money tree. In fact, in theory, there are several.

One, as Richard says, is the multiplier effect: higher public spending brings in higher tax revenues, both directly as public sector workers pay more tax and indirectly as their extra spending generates more economic activity.

Another is that governments can print money to pay for extra borrowing. The Bank of England has done ��435bn of this.

A third is that government borrowing costs are negative in real terms. Despite a slight rise recently, 20 year index-linked gilts yield minus 1.6 per cent. This means that for every ��100 the government borrows, it will have to pay back only ��72. This fact, combined with even moderate economic growth, means the government could borrow more and still see government debt shrink over time relative to GDP. It is just plain wrong, therefore, to claim that paying public sector workers more will impose a burden upon future generations.

There are, therefore, magic money trees. The fact that Ms May could claim otherwise is yet more evidence of the stupidity of her government. And the fact she wasn't sufficiently corrected for her error is evidence of the inadequacy of the media.

Just because you���ve got a magic money tree, however, doesn���t mean you must shake it. There���s a simple reason why governments have been loath to use these trees: inflation. Higher government spending means increased aggregate demand, which ��� it has been thought ��� leads to higher inflation.

It���s inflation, and not the lack of a magic money tree, which has traditionally been the obstacle to higher public spending.

Which brings me to why I agree with Richard. This danger isn���t especially great.

I don���t say this because I believe a little more inflation will be a good thing. I suspect that higher inflation might actually be a contractionary force as it might encourage households to save more ��� a danger which is especially great given that the savings ratio is at a record low now. I share Eric���s concern that lower real rates now might actually be a bad thing.

Instead, I���ve another reason not to worry much about inflation. It���s that additional economic activity doesn���t seem to be as inflationary as previously thought. We know this because wage inflation has stayed low despite unemployment falling to a 42-year low. The UK���s rising inflation now seems to be just the effect of sterling���s devaluation, which should be one-off. (This isn���t a quirk of the UK economy: much the same is true in the US too).

This might be because there���s hidden unemployment: the Resolution Foundation estimates that underemployment is greater now than in the mid-00s. Or it might be because, as Andy Haldane has said (pdf), changing working practices have led to a flatter Phillips curve. As Simon says, the Nairu has fallen. Or it might just be that in an open economy the trade-off between growth and inflation isn���t as great as people think.

Whatever the reason, the inference is the same. The government might be able to borrow more to pay public sector workers more simply because the inflation constraint on it doing so is weak.

Of course, I might be wrong here. Maybe there will come a point when stronger economic activity is inflationary. Or maybe higher public sector wages will lead to general inflation if it triggers higher private sector wages. This is an especial risk because wage rises won���t be offset by productivity gains.

If I am wrong, though, there���s a simple solution: higher interest rates. A mix of these plus looser fiscal policy would have some advantages. They���d take us away from the zero bound and so give the Bank of England more room to loosen policy in the next downturn. And they���d tend to dampen down house prices and financial speculation.

I suspect, then, that the risk of giving public sector workers a pay rise is small. Not only is there a magic money tree, therefore, but we should shake it.

July 4, 2017

The Tories' structural problem

Martin O���Neill says the Tories have forgotten to offer voters anything other than austerity. For me, this poses a question. Is the Tories��� disarray simply because of the profound mediocrity of its personnel ��� a malaise so great there���s talk of them having to recruit their next leader from the 19th century? Or is there instead a structural problem?

To see my point, let���s think in terms of a paradigm proposed by James O���Connor in The Fiscal Crisis of the State. The state in capitalist society, he argued, must fulfill two functions: legitimation, or keeping the people happy; and accumulation, promoting profits growth. Successful political parties will achieve both, albeit perhaps to different degrees.

Sometimes, these two functions go together. For example, post-war social democracy did both, until the 1970s. Sometimes, they conflict. Thatcherism, for example, was about increasing profits by bashing the working class ��� which was good (temporarily) for accumulation but less so for legitimation. Brexit is an example of them conflicting; it's OK for legitimation as it gives voters what they want, but it's bad for accumulation.

We now have a problem of legitimation. Voters are only lukewarm about the merits of capitalism, and workers of most ages voted Labour. People are ���increasingly fed up of a dog-eat-dog society in which they see reward and opportunity cluster around the already privileged��� says Phil. And Jonn writes:

Today's kids, after all, are facing a world in which wages have been flat for a decade, jobs are increasingly insecure, and home ownership is basically off the table. Most of their parents may not have had university educations ��� but they did have access to decent jobs and secure housing and at least some sense that if they worked hard they could have nice things.

That link between effort and reward has been broken for some time ��� yet successive governments have ignored the fact.

In this sense, Simon is right ��� neoliberalism has over-reached itself. The rich have forgotten that successful parasites must not make their host too ill.

But there���s also an accumulation crisis. Productivity has flatlined for ten years: it's this that underpins the discontent identified by Jonn. And for years capitalists haven���t been investing their retained profits.

Labour is offering reasonable answers to these twin problems. Ending austerity would raise growth. Socialized investment (via a National Investment Bank and infrastructure spending) would raise capital spending, and perhaps the spread of worker coops would raise productivity.

But what���s the Tories��� answer? Ms May, to her credit, identified the legitimation crisis in her ���burning injustices��� speech on becoming Prime Minister. But as Eddie Mair helpfully pointed out, the Tories have ditched plans to address them.

And whilst many Tories see a case for lessening austerity, they do so from the point of view of legitimation rather than accumulation. They cannot argue that less austerity would raise growth, because to do so would be to admit that the last seven years have been counter-productive.

Nor have they any other answers to the accumulation problem. A big reason why they have for years blamed poor economic performance upon immigrants, big government or the EU is that they cannot see that capitalism itself might be at fault. Which is why I suspect the Tories��� weakness might be more profound than the perhaps temporary one of inadequate leaders. They are, at least for now, constitutionally unable to see that our problems stem in large part from dysfunctional capitalism.

June 29, 2017

Selecting for groupthink

Stephen Buranyi says the scam that is academic publishing ���actually holds back scientific progress���:

Given a choice of projects, a scientist will almost always reject both the prosaic work of confirming or disproving past studies, and the decades-long pursuit of a risky ���moonshot���, in favour of a middle ground: a topic that is popular with editors and likely to yield regular publications.

The FCA says that active fund managers ���did not outperform their own benchmarks after fees.���

These two observations are related. They show us that selection mechanisms ��� peer review, hiring fund managers and the funds market ��� don���t necessarily select for the best. A new paper (pdf) by George Akerlof and Pascal Michaillat discusses one way in which this can happen.

They start from some experiments with flour beetles in the 1950s and 60s. These found that when two different species were placed into jars of flour, it was not the case that the most biologically fit species came to dominate. Instead, sometimes one species did and sometimes the other. The reason for this was because the species were more likely to eat the eggs of the other species than those of their own. This meant that when one species increased relative to the other ��� perhaps for arbitrary reasons ��� it continued to increase still further. Such an ���egg-eating bias���, say Akerlof and Michaillat, means that in science unfit paradigms might prevail over fitter ones - as Buranyi claims.

The egg-eating bias takes the form of professors or journal editors preferring candidates or papers in their own image ��� ones that work in their paradigm. This is sometimes because of simple favouritism. But it can also be simply because it���s easier to evaluate someone���s work if it is like your own.

This fits with the claims in economics that bad paradigms ��� such as (pdf) DSGE (pdf) or CAPM ��� have prevailed despite their empirical flaws.

It also fits with the poor performance of fund managers. One reason for this is that older fund managers hire and train younger ones on the basis of judgment-based stock selection rather than their ability to exploit proven means of beating the market such (pdf) as defensive or momentum investing. And as Bjorn-Christopher Witte shows, market forces do not necessarily weed out bad managers and favour good: markets are imperfect and sometimes perhaps even counter-productive selection mechanisms.

It also, of course, has implications for corporate management. It���s consistent with work by Dan Bernhardt, Eric Hughson and Edward Kutsoati who show that because bosses favour underlings in their own image, firms can become increasingly inefficient: for example, as finance-types exclude engineers. In the same vein, Eric Van den Steen has described (pdf) how ���organizations have an innate tendency to develop homogeneous beliefs���. This is because like hires like, and then people learn from those similar to themselves.

You can also, of course, tell a story about gender bias along these lines. (And, of course, about the media).

The point here is simple. Institutions ��� be they markets, firms, universities, publishers or whatever ��� are (among other things) selection mechanisms. We should not assume that such mechanisms work perfectly to optimize efficiency or truth. We must look under the bonnet to ask how exactly they work, rather than tell ourselves just-so stories.

In particular, institutions select ��� perhaps not entirely intentionally ��� against cognitive diversity and for groupthink. But as John Stuart Mill warned, this can be ���a social tyranny more formidable than many kinds of political oppression��� which can end up ���enslaving the soul itself.���

June 28, 2017

Why libertarians should read Marx

Kristian Niemietz says he can���t be bothered to read Marx. Can I try and convince him otherwise?

For one thing, I suspect libertarians like him would be surprised by a lot of Marx. There���s astonishingly little in Marx about a centrally planned economy: if you want an argument for central planning, you should read that hero of the right, Ronald Coase instead (pdf). Marx was admiring of capitalism in some respects. It has, he wrote, given ���an immense development to commerce��� and has ���accomplished wonders far surpassing Egyptian pyramids, Roman aqueducts, and Gothic cathedrals.��� And I think you���d be surprised by just how much attention Marx paid to the facts: once you get past the first few chapters, there���s massive empirical work in Capital volume I*. And there are many differences between Marx and social democrats ��� not least of them being that Marx was no statist.

What���s more, many of the ideas associated with Marx were largely elaborations of his predecessors: Paul Samuelson called him a ���minor post-Ricardian���. The labour theory of value, the interest in the division of income between classes and the idea of a falling rate of profit are all as Ricardian as Marxian. (The falling rate of profit (pdf) might be a good explanation for our recent slow growth and lack of capital spending, but let that pass).

I reckon there are three reasons libertarians should read Marx.

One is that Marx saw economics as a historical process. For him, one of the big questions was: ���where did that come from?���

For him, capitalism ��� understood not as a market economy but one in which capital hired labour ��� was not a ���natural��� phenomenon but rather something that came into the world ���dripping from head to foot, from every pore, with blood and dirt.��� It was founded on theft and slavery ��� the denial of the rights and freedom which libertarians celebrate. This poses a challenge: insofar as today���s economy is founded upon past injustices, how can they be regarded as legitimate? Many libertarians��� answers strike me as facile.

Also, our ideas don���t come from nowhere. They are instead a product of technical and economic circumstances: ���the mode of production of material life conditions the social, political and intellectual life process in general.��� If you want to hear Marxism at the BBC, ignore the news and listen instead to The Digital Human. Conventional economic research supports Marx in this. For example, Jeremy Greenwood has shown how the spread of household goods contributed greatly to increased gender equality. When we think about new technologies, we should remember that robots and AI won���t just change how we work (or whether we do) but also how we think.

One implication of this for libertarians is that they must ask: what material economic basis would make our ideas more popular? I���d argue that one such basis is greater equality, as this would diminish demands for statist regulation.

Another implication is that our ideas might be distorted. ���The ideas of the ruling class are in every epoch the ruling ideas, i.e. the class which is the ruling material force of society, is at the same time its ruling intellectual force��� wrote Marx. This has been interpreted along crude conspiracist lines. But another (perhaps generous) reading is that our attitudes to the existing order can be shaped by cognitive biases which help to reinforce that order. Whilst I���ve interpreted this in a Marxian way, such an approach might also help reinforce Bryan Caplan���s work (pdf) on why voters reject free market policies.

A second reason for libertarians to read Marx lies in his view of the relationship between property rights and technical progress:

At a certain stage of their development, the material productive forces of society come in conflict with the existing relations of production, or ��� what is but a legal expression for the same thing ��� with the property relations within which they have been at work hitherto. From forms of development of the productive forces these relations turn into their fetters.

This might speak to our current secular stagnation. Why are productivity growth and capital spending so weak? Might one reason be that the fear of future losses from competition is deterring investment? Or that excessively tight intellectual property laws are restricting innovation? Marx poses the question: how should property rights alter to foster growth? This surely should interest libertarians.

A third reason to read Marx lies in his attitudes to freedom. Marx���s main gripe with capitalism wasn���t so much that it was unfair but that it thwarted our freedom to develop our human potential. Work, instead of being a source of self-expression, is oppressive and alienating under capitalism:

Within the capitalist system all methods for raising the social productiveness of labour are brought about at the cost of the individual labourer; all means for the development of production transform themselves into means of domination over, and exploitation of, the producers; they mutilate the labourer into a fragment of a man, degrade him to the level of an appendage of a machine, destroy every remnant of charm in his work and turn it into a hated toil; they estrange from him the intellectual potentialities of the labour process.

A big reason for this, thought Marx, was that workers lack the power to fight for real freedom. The market, he wrote, is the realm of ���Freedom, Equality, Property and Bentham.��� But, he continued, when we leave this ���sphere of exchange of commodities��� and enter the ���hidden abode of production���, we see inequality and oppression:

He, who before was the money-owner, now strides in front as capitalist; the possessor of labour-power follows as his labourer. The one with an air of importance, smirking, intent on business; the other, timid and holding back, like one who is bringing his own hide to market and has nothing to expect but ��� a hiding.

Granted, working hours and conditions have improved since Marx���s day ��� but for many they remain oppressive for many.

In short, then, libertarians should read Marx because he poses them some questions which should sharpen their thinking. How can we defend property rights at the same time as defending a system which came into being by denying those rights? What material conditions are necessary for people to support freedom? How will new technologies shape our beliefs? Do current market structures (which are of course determined by the state) really maximize development? If not, how can they change? Do actually-existing markets merely enhance formal freedom, or are they conducive to the substantive freedom that Marx wanted? Can they be made more conducive? Are markets really a realm of freedom, or a means through which some exploit and oppress others? And so on.

If you look past tribal caricatures, perhaps libertarian thinking will be enriched by a consideration of Marx���s work.

* You should start Capital vol I at chapter 10, and read the first nine chapters last.

June 26, 2017

On political salience

One aspect of politics that is perhaps under-appreciated is the question: who gets to decide, and how, which issues become prominent and which not?

I say this because on the Sunday Politics yesterday, Andrew Neil interviewed Gerard Coyne (23'20" in). This is odd. How often does the BBC give such prominence to former regional secretaries of trades unions? Even if Mr Coyne���s allegations of Stalinism at Unite are wholly valid, do they really deserve such attention? Of course, I���d be the first to deplore intolerance of dissent. But this is common in many workplaces, among them Ms May���s: it might well have been a significant contributor to the financial crisis. I'd love to see more debate about the scarring effects of groupthink, hierarchy and suppression of dissent. But why discuss these in a union, and ignore them in companies and in politics?

This is one way in which BBC bias works. Bias isn���t just ��� or even mainly ��� slanted reporting of particular issues. It also consists in deciding what to report. Giving prominence to a story which might reflect discredit upon Unite whilst ignoring dictatorial management in other organizations is a form of bias.

I don���t say this merely to complain about the BBC again. Instead, it���s to make the point that power and political skill isn���t merely a matter of being able to get what you want. It���s about being able to put some matters on the agenda whilst keeping others off it. For example, the achievement Brexiters wasn���t merely to win the referendum but to get the obscurantist obsession of a few cranks to a dominant position onto the political agenda in the first place.

Jeremy Corbyn, though, has achieved a similar feat. He���s raised the salience of an issue on which Labour is strong ��� austerity- whilst reducing the salience of issues on which it is weak. The party���s policies on immigration and Brexit leave something to be desired, but Corbyn has ��� for now ��� downgraded their visibility.

These, however, are exceptions. Generally speaking, the matter of what is salient and what not serves reactionary purposes. For example, the merits (or not) of land value tax, citizens income or coops are insufficiently debated in the MSM. And important questions are downplayed such as: to what extent is the long stagnation of labour productivity a symptom of capitalist dysfunction? Why are real interest rates negative and what does it imply for fiscal policy? Under what conditions is hierarchy efficient? Why has CEO pay exploded since the 1980s? Is it possible to increase job satisfaction and if so how? And so on. If questions such as these were more salient ��� the BBC rarely discusses them ��� politics would surely look very different.

Such questions would, of course, bring class struggle more into politics. But then, as Steven Lukes wrote. ���the most effective and insidious use of power is to prevent���conflict from arising in the first place.��� (Power, a radical view, p27) One challenge for the left is to fight this power by asking the questions we want to, and not merely accepting the right's agenda.

June 23, 2017

A case against austerity

Some Tories say voters are tired and weary of austerity*. The voters are right.

Let���s start with the sums. There���s a simple equation to tell us what primary budget balance we need to stabilize the debt-GDP ratio (the primary balance is annual borrowing excluding interest payments). The equation is:

d * [(r-g)/(1+g)]

where d is the debt-GDP ratio, r the real interest rate and g is trend growth. D is now 86.5% and r (measured by the 20 year index-linked gilt yield) is minus 1.7%. Let���s be cautious and call g 1.5%. Our equation then tells us that we can stabilize the debt-GDP ratio even with a deficit of 2.7% of GDP. However, the present deficit is only 0.9% of GDP, and the government���s current plans envisage a surplus after 2019.

The government can therefore borrow a lot more than it is currently and still reduce the debt-GDP ratio. That���s the beauty of negative real interest rates.

This poses the question: should we really aim to cut the debt-GDP ratio as fast as the Tories plan?

There are two reasons to think not. One is that fiscal tightness depresses GDP growth and this cannot be adequately offset by monetary policy when we���re near the zero bound. The other is that there is a global (pdf) safe asset shortage, which means that high stocks of government debt (safe assets) are now more sustainable than they were in the 80s or 90s.

There are two counter-arguments to this. One is that we need to cut government debt now to give us fiscal space for a loosening in the next recession. The other is that the strong demand for government debt might not last. These arguments, however, seem to me to be mutually exclusive: in a downturn, demand for safe assets will rise**.

There���s another reason to end austerity. It���s that Osborne���s way of doing so achieved the impressive physical feat of being half-arsed and cack-handed. Serious efforts to cut government spending would have done three things:

- They would have created an ideological climate conducive to smaller government.

- They would have reduced the functions of government: it���s easier to do less with less than to do more with less. For example, if you cut police numbers, you should cut the crimes they investigate ��� say by legalizing drugs or sex work. If want fewer prison officers you should cut the number of prisoners. And if you want a slimline civil service, you shouldn���t give it the gargantuan task of organizing and negotiating Brexit.

- They would empower workers who know the ground truth of how the public sector wastes money.

The Tories have done none of these. As Sam says, they ���have totally failed to make a broad-brush case for free markets.��� They���ve tried instead to cut spending by top-down managerialism. The upshot has been that those cuts have been unsustainable. As Rick says, even small further cuts ���might be enough to tip some public services over the edge.���

You might reply here that government spending, at just under 40% of GDP now, is too high given that an ageing population will increase such spending in future.

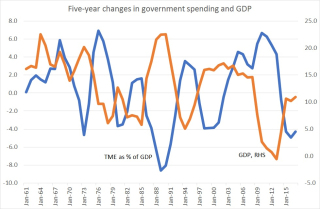

In this context, my chart tells an important story. It shows that there���s a significant negative correlation between five-year changes in the share of government spending in GDP and GDP growth. Faster GDP growth ��� such as in the early 70s, late 80s and early 00s ��� is associated with falls in public spending as a share of GDP. And slower growth ��� such as the recessions of the mid-70s, early 80s and 2008-09 ��� see increases in that share.

If you want to shrink the ratio of public spending to GDP, therefore, it���s much easier to do so if the denominator is rising strongly. We must, therefore, try to increase trend growth. In this context, it might be that austerity is counter-productive in another sense ��� because, as Simon says, it might have depressed trend growth. Whatever, policies to increase productivity are imperative.

You might object here that such policies won���t work because it���s just damned hard to increase (pdf) trend growth. Maybe. To which I say: let���s test the hypothesis with rigorous policy action.

* I'm defining austerity by the change in the cyclically-adjusted primary budget deficit. This has been cut fro, 6.4% of GDP in 2009-10 to 0.9% now.

** Also, even if you plug a plausibly higher r into my equation, you still get a similar outcome ��� that we don���t need a surplus to cut the debt-GDP ratio.

June 22, 2017

The lack of demand for equality

Why do people tolerate inequality? A new paper by Karl Ove Moene and colleagues provides a new explanation: it���s because a small role for merit in income inequality causes a big drop in demand for redistribution.

They showed this in some experiments. Over 1000 people were asked to observe pairs of people working on a task for ten minutes, with earnings divided between the pairs in different ways. The spectators were then invited to redistribute some or all of those earnings.

When told that one worker got everything and another nothing simply because of a lottery, 68% of spectators chose to equalize earnings. However, when told that everything went to the worker who had done best, only 28% equalized earnings. This is consistent with most people being luck egalitarians; they want to eliminate inequalities that are due to luck, but accept those due to differences in merit or effort.

But here���s the quirk. Other subjects were told that earnings were divided 90% by luck and 10% by merit. You���d expect these to redistribute almost as much as those subjects faced with inequalities due entirely to luck. But they didn���t. Only 22% chose to equalize earnings. ���A little bit of merit makes people significantly more inequality accepting��� conclude the authors.

A tiny role for merit reduces demand for redistribution as much as a big role does.

Of course, sceptics will question the external validity of this result. I suspect, though, that in the real world it might be amplified by the hindsight bias. When we see successful people, we infer that they must have done something to earn that success and so we downgrade the importance of dumb luck.

This, of course, is not the only reason why people tolerate inequality. In fact, this phenomenon might be overdetermined. Here are some other theories:

- Ignorance. ���People dramatically underestimate actual pay inequality��� say Sorapap Kiatpongsan and Michael Norton. Ratios of CEO pay to that of unskilled workers are far higher than people think, and even higher than they believe desirable.

- Anchoring. Kris-Stella Trump has shown that our idea of what is an acceptable level of inequality is shaped by actual inequality. As inequality rises, therefore, so too does our view of tolerable inequality. In the same vein, Jimmy Charitie, Raymond Fisman and Ilyana Kuziemko have shown how preferences for redistribution are influenced (pdf) by reference points. If people expect incomes to be equal, they���ll demand more redistribution than if they expect unequal incomes.

- System justification. John Jost and colleagues have shown (pdf) how people tell themselves stories to justify inequality, such as blaming the victim or believing injustice to be natural.

I say all this to make a point to both left and right. To the right, I suggest that a lack of demand for redistribution need not be evidence that inequalities are just. It might instead be that attitudes are distorted by cognitive biases. To the left, I suggest that we worry less about people being influenced by the right-wing media ��� the election result suggests such influence is less than previously thought ��� and more about how pro-inequality ideology can emerge endogenously from the interplay of capitalism and cognitive biases.

June 21, 2017

Free markets need equality

These are dark times for free marketeers. Voters are only lukewarm about the virtues of capitalism; the Grenfell disaster is widely regarded as showing the case for greater regulation; and, as Sam Bowman says, even the Tories ���have totally failed to make a broad-brush case for free markets.���

I share some of their disquiet. Flawed as they are, markets have virtues as selection and information-aggregation mechanisms.

What, then, can be done to strengthen the case for markets?

There���s one thing that���s crucial ��� equality of power. For free markets to have public acceptance, the worst-off must have bargaining power. Without this, ���free��� markets merely become a device for exploitation.

Imagine, for example, that we had overfull employment and/or high out-of-work benefits. Workers would then be able to reject low wages and bad working conditions. Market forces would then deliver higher wages and good, safer, conditions simply because employers that didn���t offer these wouldn���t have any workers. Equally ��� though it���s harder to imagine ��� if we had an abundance of housing, landlords who offered shoddy or dangerous accommodation would either have to refurbish their property to acceptable standards or suffer a lack of tenants.

We wouldn���t, therefore need ���red tape.��� The market would raise working and living standards.

We don���t need thought experiments to see this. We have empirical evidence too.

Philippe Aghion and colleagues have shown that there���s a negative correlation across countries between unions density and minimum wage laws. Countries with strong unions have less stringent minimum wage laws ��� because greater bargaining power reduces the need for such laws. Remember that the UK adopted minimum wages in the 1990s, when unions had been emasculated. In the 60s and 70s, when unions were strong, the market raised wages.

Also, there is a negative correlation across developed countries between inequality (as measured, imperfectly, by Gini coefficients) and business freedom. Egalitarian Denmark and Sweden, for example, score better on the Heritage Foundation���s index of freedom than the unequal US. There���s a simple reason for this. Working people want what they regard as a fair deal. If they can���t get it through bargaining in free markets, they���ll seek it through politics and regulation.

The inference here is, for me, obvious. If you are serious about wanting free markets you must put in place the conditions which are necessary for them ��� namely, greater bargaining power for tenants, customers and workers. This requires not just strong anti-monopoly policies but also policies such as a high citizens income, full employment and mass housebuilding.

In short, free markets require egalitarian policies. Free marketeers who don���t support these are not the friends of freedom at all, but are merely shills for exploiters.

Chris Dillow's Blog

- Chris Dillow's profile

- 2 followers