Chris Dillow's Blog, page 59

June 20, 2017

Selecting for Corbynism

There seems to be a paradox about Corbynism. On the one hand, I feel the force of claims that Labour���s manifesto was quite right-wing. Matt Bolton says that it���s immigration policy was ���well to the right of the 2015 manifesto���, and John Rentoul has complained that Labour offered little to low-paid workers facing benefit cuts. But on the other hand, I sympathize with Joe Guinan and Thomas Hanna���s claim that Corbynism ���contains the seeds of a radical transformation beyond social democracy.���

So, what���s going on?

For one thing, Corbyn (rightly) reduced the salience of immigration as an issue: unlike Ed Miliband, he didn���t put any promise to cut migration onto mugs. And for another, there was an element of Nixon going to China or McGuinness bringing peace to Northern Ireland about Labour. As Matt says, Corbyn was so well-trusted on the left that his rightist policies on welfare and migration were tolerated as good triangulation rather than as a sell-out.

But perhaps there���s something else. Maybe the ideological climate is changing. The collapse of Ukip as an electoral threat meant that Corbyn was more fortunate than Miliband in not having to dwell on immigration, whilst voters��� weariness with austerity played to Labour���s strengths.

My perhaps forlorn hope is that the climate will continue to change. The ongoing stagnation of real wages might highlight capitalism���s inadequacies: the Ashcroft polls already show only mild support for the system among working-age people (Table 31 of this pdf). The Grenfell disaster has shown that deregulation and unequal bargaining power are a horrible combination. The contrast between the self-help of residents with the chaos of the official response to the catastrophe should highlight the case for economic democracy over hierarchy. And the Barclays fraud trial might shed light upon some of the murkier aspects of finance.

What I hope we���re seeing, therefore, is an example of what Janan Ganesh says:

We have all seen ideas pass from the unthinkable to the inevitable ��� and vice versa ��� without any political design from above.

To understand what���s going on here, it might help to change our mental model of politics. Rather than think of politicians as deliberately choosing policies and attitudes that sell to voters, with talented ones doing well and poor ones not, we should think instead of politics as being like natural selection or market selection. Species, or companies, or politicians, adopt strategies more or less blindly (because the world is unknowable) and the environment then selects among those strategies ��� not necessarily optimally.

Maybe the political environment is changing to select in favour of Corbynism and against Toryism. It���s not that Corbyn is a genius, but that ��� if we���re lucky - he���s the right(ish) man at the right time.

June 18, 2017

The end of the cosy game of politics

There���s one aspect of the Grenfell catastrophe that is perhaps under-appreciated ��� that it should finally kill off what is perhaps the dominant conception of politics in the media.

I���m thinking here of the idea that politics is an Oxford Union-style game. There���s jockeying for position, gossip and backbiting in which (over)-confidence, fluency and a particular conception of ���credibility��� are prized above all, but the game is mostly among jolly good chaps. And it���s a low-stakes one. The worst crime is to conduct a ���car crash��� interview, and the losers retire to spend more time with their trust funds and sinecures.

We see this idea of politics in the matey undertow between presenters such as John Pienaar and Andrew Neil and their narrow roster of guests; the idea that politics is something that only happens in Westminster; the ostracism and patronizing of those whose class, gender or ethnicity excludes them from the game, such as John Prescott, Angela Rayner and Diane Abbott; and the popularity of Boris Johnson, the epitome of Oxford Union politics. One reason why John McDonnell is so hated is that he sees that politics is not just a debating game.

This idea of politics is, though, a lie. The truth is that politics has always been a matter of life and death ��� especially (though not only) for the worst off.

For me, one of the most memorable political exchanges of the 1980s was when a heckler shouted to Neil Kinnock that Thatcher had ���showed guts���, to which Kinnock replied: "It's a pity others had to leave theirs on the ground at Goose Green to prove it." That retort caused outrage because it reminded the political class of the nasty fact that political decisions, rightly or wrongly, have lethal consequences.

And not just on battlefields. There���s a line through the countless deaths in, mines, factories and building sites through Aberfan and Hillsborough to the suicides caused by benefit cuts. That line has led to the smouldering remains of Grenfell tower. David Lammy's righteous anger is the latest reminder of the fact the political class would rather forget.

The lie that politics is just a cosy game has been perpetuated in recent years by hiding the real effects of austerity behind dry statistics and by effacing ground truth by the ���he says, he says��� claim and counter-claim of ���impartial��� reporting.

More than that, though, it is sustained by excluding the worst off from the cosy game. For centuries the poor have been, in C.B Macpherson���s words ���in but not of civil society���: they have been a problem to be managed and silenced, not agents deserving of power. (New Labour was perhaps as guilty of this as the Tories).

In this context, the right���s attempts to blame the disaster upon state rather than market failure misses the point. Not only does privatization and contracting out blur the distinction between state and market, but also state and market have long been two mechanisms with similar effects*: they suppress, exploit and marginalize the poor.

It���s in this sense that the contrast between those images of May and Corbyn is so powerful. May���s avoiding the Grenfell tenants confirmed the traditional hierarchical view that the poor have no place in politics: Corbyn���s comforting them rejected this and showed that politicians and the poor should be equals.

Herein lies my hope. Grenfell might ��� just might - be a turning point. It shows that politics can no longer be seen as a debating game from which the poor are excluded. It must instead become a serious matter which has life and death consequences, in which the interests and voices of the worst off are finally given full value, and in which there's no place for childish games.

* This is of course not to say these are their only effects.

June 16, 2017

The landlords' party

Owen Jones says the Tories are the ���Landlords Party���. This is true in a deeper sense than the mere fact that so many Tory MPs are themselves landlords. It���s because fiscal austerity has contributed to rising house prices.

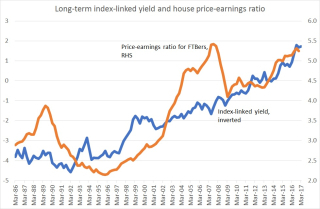

There���s a simple reason for this. Fiscal conservatism and monetary activism ��� to use Osborne���s phrase ��� means low interest rates, low expected rates and low gilt yields. And as the Bank of England said (pdf), this means higher asset prices generally. This is simply because lower rates mean that future rents are discounted less heavily, which raises their net present value. As Simon said:

Just as low real interest rates boost the stock market because a given stream of expected future dividends looks more attractive, much the same is true of housing (where dividends become rents). Stock prices can rise because expected future profitability increases, but they can also rise because expected real interest rates fall. With housing increasingly used as an asset for the wealthy, or even as a way of saving for retirement, house prices will behave in a similar way.

My chart shows the point. It shows that lower index-linked yields have been accompanied by higher ratios of house prices to incomes. Yes, fiscal austerity means lower incomes and hence lower house prices, other things equal. But in reality, that mechanism has been more than offset by lower interest rates. And yes, George Osborne hit buy-to-let landlords with higher taxes ��� which perhaps vindicates Phil���s point that the Tory party ���has not been a suitable vehicle for the interests it's supposed to represent.��� And of course, austerity is one of only many causes of low real yields ��� many of which are global. But it has contributed to low yields and hence higher house prices.

On balance, though, the Tories have probably been good for landlords. This explains one of YouGov���s findings (pdf) ��� that homeowners vote Tory. 53% of these voted Tory against only 31% voting Labour, whereas among renters Labour led by 51% to 32%.

Which brings me to a problem. High house prices are probably, net, bad for the economy.

Granted, they provide collateral and so allow potential entrepreneurs to borrow. But this mechanism is offset by others. Rising house prices encourage banks to lend against property rather than to productive new firms. High rents depress disposable incomes and so reduce demand for new goods and services. High house prices lead (pdf) to long commutes and less job mobility which depresses productivity. And rising prices incentivize ���property development��� rather than more dynamic forms of entrepreneurship.

I suspect, therefore, that the Tories are now rather like the party they were in the days of the Corn Laws: they represent interests which are hostile to economic progress.

There is of course nothing original in the claim that landlords��� interests are a block on economic growth. As somebody once said:

Unearned increments in land are not the only form of unearned or undeserved profit, but they are the principal form of unearned increment, and they are derived from processes which are not merely not beneficial, but positively detrimental to the general public���The land monopolist only has to sit still and watch complacently his property multiplying in value, sometimes many fold, without either effort or contribution on his part!

That was Winston Churchill in 1909. Tories like to compare themselves to him. But in one respect at least, they are more reactionary now than he was a century ago.

June 15, 2017

Political pundits' biases

Everybody agrees that political journalists and pundits were big losers in the general election. As Jon Stone points out, many of their cherished presuppositions turned out to be wrong.

Here���s a theory as to why. It���s because of deformation professionelle. Every occupation has a way of approaching issues which, whilst useful in many ways, also tends to distort their perspective. For example, engineers over-rate the extent to which everything is an engineering problem; lawyers put too much faith in the power of the law; and economists have traditionally over-emphasized extrinsic incentives.

Political commentators are no different. Their perspective too is distorted ��� a distortion is magnified by the sort of groupthink described by George Monbiot.

One such distortion is that they pay too much attention to Westminster and too little to the ground truth of grassroots politics. For example, in his admirable review of his errors* John Rentoul says he under-estimated voters��� hostility to capitalism and desire for optimism and compassion in a leader. This might be because his antennae were too attuned to Westminster and insufficiently to the country.

This was an especially grave mistake because Corbynism is a different type of politics. It pays less heed to the Blairite virtues of day-to-day news management and more to building party membership, mobilizing what Phil calls the networked worker and getting out the youth vote (where ���youth is anyone under 47).

John wasn���t alone in this of course. Jonathan Dean says of political scientists:

had we moved our gaze beyond Westminster-centred electoral politics to encompass, for instance, work by cultural studies scholars on the connections between youth culture and ideology, black feminists on race, gender and political solidarity, or literature on social movements and activism, we might have been better able to properly make sense of Corbynism.

Relatedly, pundits pay too much attention to personalities and too little to policy. They commit the error of which Richard Sennett complained 40 years ago:

A political leader running for office is spoken of as "credible" or "legitimate" in terms of what kind of man he is, rather than in terms of the actions or programmes he espouses. The obsession with persons at the expense of more impersonal social relations is like a filter which discolours our rational understanding of society. (The Fall of Public Man, p4)

Tom Mills points to a good example of this. The leaking of Labour���s manifesto was reported as a failure of Corbyn���s party management when it could instead have been seen as a set of popular policies.

Such a focus upon political leaders would not be so bad if it were clear-eyed. But it���s not. ���Strong��� leadership is seen too much in terms of party unity, and too little in terms of good, inclusive decision-making. We know now that May was gravely weakened by her excessive reliance on too narrow a group of advisors ��� but Westminster journalists were perhaps better at pointing this out in hindsight than they were weeks ago.

Finally (for now!), there���s been a tendency to regard politics as an exercise in marketing. Far too often, Corbyn and his policies were dismissed as simply ���unelectable���. One happy effect of this election should be that Corbyn���s critics will speak less of electability and instead debate policies on their (de)merits.

My point here is not that political correspondents are uniquely biased: all professionals are. What I am doing, though, is raising questions about the BBC. How can we reconcile the organization���s supposed commitment to impartiality with the fact that its Westminster correspondents have particular biases?

* I don���t like the words ���error��� and ���mistake���. They have connotations of deviation from a normal condition of being right when in fact in emergent systems such as politics, economics (and financial markets) mistakes are so common as to be routine. We should stigmatize mistakes less, but put more stigma onto the failure to learn from them.

June 11, 2017

The changing class divide

Social class has become less important as an influence upon voting behaviour. This is one under-appreciated feature of last week���s election.

Lord Ashcroft���s polls show that the social class AB split 43%-34% between the Tories and Labour. That meant Corbyn���s Labour got a higher share of the well-off���s vote than Blair���s Labour got in 1997, when it got 31%. Labour���s wins in Kensington and Canterbury are the most spectacular manifestations of this.

The difference between Blair and Corbyn is that Blair did far better than Corbyn among the working class. The DE group split 59-21 for Labour in 1997 but only 45-33 in 2017.

This seems to conflict with decades of conventional wisdom. A so-called ���hard left��� Labour leader has had support from a wider class base than a so-called ���modernizer��� who consciously tried for such classless support.

How can this be? I���d suggest three reasons.

One is Brexit. The ABs voted 57-43 for Remain, whereas the DEs went 64-36 for Leave. May���s hard Brexit thus alienated some ABs, and made Labour���s softer stand on Brexit more attractive.

Secondly, Corbyn���s domestic policy was one of universalism more than sectarian class war. His offer of free childcare and the abolition of university fees appealed to many ABs. By contrast, his failure to promise to raise working tax credits meant he was offering relatively little to the DEs. John Rentoul has a point that Corbyn was insufficiently radical ��� but therein perhaps lay some of his appeal.

Thirdly, Corbyn���s promise to tax the very rich appealed to those ABs (the majority) earning less than ��80,000. Reference group theory implies that people compare themselves with those like themselves. So, someone on say ��50,000 a year might ask: ���why is that idiot earning twice as much as me when he���s no smarter?��� Many ABs, I suspect, are more aware than the DEs that many of the very rich are incompetent rent-seekers rather than the ���wealth creators��� of Tory myth. A DE voter, on the other hand, has almost no contact with the rich but is instead irritated by benefit claimants.

This tendency is exacerbated by another ��� that, as Rick said, the middle classes aren���t as posh as they used to be. Many work long hours in unfulfilling jobs for oppressive bosses with no hope of buying a decent house. For them, Corbynite talk of rent controls and housebuilding was an attractive offer relative to a Tory party than was offering nothing.

It���s in this context that class still matters. Yes, the Tory-Labour split is no longer a class split. But this is because the class basis of Toryism has diminished. What we���ve seen in recent years is a hollowing out of the middle class. A rising take by the top 1% has been accompanied by the middlingly rich becoming less bourgeois: their incomes have fallen relative to the worst off, as I suspect, have their working conditions. This has made ABs more amenable to Labour.

In this sense, perhaps the Tories have a deeper problem than merely yet another laughably inept leader. Their problem is that they no longer articulate the interests of the class they once did, because that class has changed. Ironically, they have become the victims of the inequality that has seen the top 1% (or perhaps 0.1%) pull away from the rest of us.

June 1, 2017

Under-estimating Corbyn

Depending which opinion poll you believe, this election looks like being closer than the pundits expected. Blairites' belief that Corbyn was ���unelectable���, and May���s idea that she could win a landslide without even turning up now look doubtful. Yes, they might be correct, but the confidence interval around those views now seems wider than it did a few weeks ago. (These people don���t often deal in confidence intervals, but let that pass).

This raises the question: why have his critics under-estimated Corbyn? (We might add to this list those Labour MPs who put him on the leadership ballot in 2015 believing he couldn���t win).

I suspect there are two cognitive biases to blame. One is deformation professionnelle ��� the tendency among all professionals to see things from the perspective of their own occupation. People inside the Westminster Bubble over-estimate the importance of playing by their own rules. They���ve thought that you win elections by occupying a perhaps mythical ���centre ground���; by kowtowing to deficit fetishists and immigration-phobics; and by satisfying a managerialist conception of credibility. What this might have under-estimated is the popularity of: halfway sensible policies, a focus upon justice and living standards; and at least the appearance of basic humanity.

Another bias is the halo effect ��� the tendency to believe that someone with a few good qualities somehow possesses all virtues. In bad Hollywood movies, the villain isn���t just morally inferior to the hero but is also uglier and a worse shot. By this same reasoning, Corbyn���s faults such as poor management and terrorist associations led pundits to under-estimate his strengths such as personability and skill at campaigning and debating: his critics love to point out that Corbyn hasn���t changed his views for 30 years, but overlook the fact that this gives him the advantage of knowing his lines well.

It is of course trivially true that nobody���s perfect (a clich�� proven by the fact that Rachel Riley supports Manyoo) and few of us are entirely imperfect. What���s not so much appreciated though is that success and failure is often not a case of people being good or bad. Instead, success results from circumstances favouring our virtues, whilst failure happens when they highlight our vices. A successful hiring decision isn���t so much one that finds the best person for the job as one that finds the right match. To take an example from Boris Groysberg (pdf), two managers might be of equal overall quality but if the firm is looking to increase market share, the good marketing man will be a better hire than the good cost-cutter.

Sometimes, of course, circumstances will change so that the same man will be both a failure and a success at different times: Steve Jobs��� difficult personality both got him sacked from Apple and drove the company to huge success; and Winston Churchill���s bellicosity made him a lousy peacetime politician but a great war leader.

Which brings me to one of several questions that is curiously neglected in this election campaign. Insofar as leadership is an issue, the question shouldn���t be: who���s the best leader, but rather: do circumstances favour Corbyn���s mix of strengths and weaknesses or May���s? Idle blather about leadership is not enough: we must instead ask about the precise technology whereby leaders affect outcomes.

On writing for money

���No man but a blockhead ever wrote except for money.��� Samuel Johnson���s words have for centuries fueled a prejudice that paid writing is of higher status than the amateur equivalent. This should be challenged.

What I���m thinking of here is what Fred Hirsch called the commercialization effect. When money changes hands, he said, unspecified mutual obligations are diminished: ���the more that is in the contracts, the less can be expected without them.��� This has recently been echoed by Michael Sandel (pdf):

financial incentives and other market mechanisms can backfire by crowding out nonmarket norms.

When we write for non-financial reasons ��� the love of it, the need to say something, whatever ��� we ask: is this true? Does it need saying? Writing for money, however, is apt to downplay these questions in favour of: can I get this past the lawyers? Or: Is this what my readers want?��� And: "does this fit the space between the adverts?"

As thinkers such as Michael Walzer and Sandel have argued, the cash nexus can change the very meaning of goods. Paid sex, for example, is not the same as a one-night stand. In the same way, paid writing isn���t the same as free writing.

Personally, I suspect that a lot of my least bad writing ��� not just here but also in the IC - is stuff I���d write even if I weren���t paid to. My worse efforts have come when I���ve needed to fill space. Might the same be true of others?

Here���s a thought experiment: what sort of journalism would we see if people weren���t being paid to do it? We���d probably not see journalists harassing the bereaved; or phone-hacking; or heavy pro-Brexit bias; or the sidebar of shame; or so much anti-Labour bias; or so much neglect of poverty and inequality; or the tiresome attention-grabbing of the likes of Hopkins and Young; or attempts to blame Ariana Grande or Jeremy Corbyn for terror attacks. The paid media gives disproportionate attention to the concerns of billionaire newspaper owners, to rich editors, and to posh Londoners ��� and therefore neglects others. The cash nexus, unsurprisingly, empowers those with cash.

This isn���t to say it is wholly baleful. It can elicit some good writing. Without it we���d have much less factual reporting ��� though the paid media has long ago cut back on investigative journalism. And motive crowding-out is far from complete: I don���t apply lower standards to my day job than to the blog, and I suspect that many columnists would write what they write even if they were freed from the dull compulsion of the economic. And of course Twitter reminds us that misogyny, idiocy, cliche-mongering and racism can thrive without the paid media.

We can put this another way. Take Habermas���s notion of ideal speech. Among the criteria for this are:

(i) no one capable of making a relevant contribution has been excluded, (ii) participants have equal voice, (iii) they are internally free to speak their honest opinion without deception or self-deception, and (iv) there are no sources of coercion built into the process and procedures of discourse.

The paid media thwarts the second and third of these, and quite possibly the first and fourth too. In these respects, it coarsens the quality of democracy.

You might think all this is familiar stuff. However, the commercialization effect bemoaned by Sandel and Hirsch doesn���t just warp writing in the media. It also afflicts academia. In many fields (pdf), the profession has a replicability crisis: results that appear even in the best peer-reviewed journals are more fragile than they should be. As Helen Dale has said:

Shit papers that don't replicate peer-reviewed by people with ideological blinkers is clearly a significant issue, and not just in predatory journals. Shit books that no-one will buy published as CV-stuffers are clearly a significant issue.

A big cause of this are financial incentives. As Helen says, ���publish or perish��� rules produce perverse incentives; they encourage p-hacking, neglect of best statistical practice (pdf) and a following of intellectual fashion.

The question I asked of journalism can thus be asked of academic writing: would this appear if it weren���t for financial incentives and career concerns? Again, I suspect that in many cases the answer is: no. When clever people do silly things, incentives are often to blame.

I���m not offering any glib solutions here. What I am doing is echoing the young Marx. Money, he wrote, has a ���distorting and confounding��� effect on ���all human and natural qualities���:

Money, then, appears as this distorting power both against the individual and against the bonds of society, etc., which claim to be entities in themselves. It transforms fidelity into infidelity, love into hate, hate into love, virtue into vice, vice into virtue, servant into master, master into servant, idiocy into intelligence, and intelligence into idiocy.

Of course, there are massive offsetting benefits to a market economy. But everything has a cost.

May 30, 2017

Unsayable truths

There are some truths that politicians find it hard to express ��� and this warps our political debate. This is my reaction to a piece by Janan Ganesh.

He accuses Labour and the Tories of an ���indifference��� to economic growth, because both parties believe that the vote for Brexit was a ���cry for something more than the soulless quest for 2.5-ish per cent annual output expansion���. Such an interpretation, he says, is wrong:

The British did not brave the costs to vote for exit. They just did not believe there were costs.

As these costs become apparent, however, he warns, the country will become angrier.

For me, this is half-wrong and half-right.

It���s wrong because, as Simon says, economic growth will be higher under Labour. Its looser fiscal policy and lack of a daft migration target will raise growth, relative to what we���d see under the Tories.

True, Labour hasn���t hammered this message home. But this is because it���s a hard sell. It���s difficult to tell voters that migration controls will make them poorer. And the message that looser fiscal policy means faster growth unless fully offset by monetary policy might be basic economics. But it���s hard to get across when imbecile mediamacro demands that the ���sums add up.��� This is all the more the case when the country���s ���leading��� economic thinktank, the IFS, judges manifestos in what John Weeks calls a misguided ���partial and static approach.���

I fear Janan is right to say that voters haven���t chosen to pay the cost of Brexit. But again, this raises the same problem of a truth that can���t be said by politicians. Pointing out that voters were wrong means you'll be seen as an elitist technocrat whose out of touch with the people. Yes, the LibDems are saying this ��� but look at their poll ratings. Politics is dominated by a mental model which sees voters as sovereign consumers. This means politicians can no more tell voters they���re wrong any more than companies can tell customers they are. Even when it���s true, it���s god-awful marketing.

I also agree with Janan that weak growth has fuelled public anger and will continue to do so.

But here���s the problem: at whom will this anger be directed? So far, it has been at immigrants: for me, it���s pretty clear that stagnation contributed to the demand for Brexit. That fits the pattern described by Markus Brueckner and Hans Peter Gruener and Ben Friedman ��� for weak growth to breed insularity, intolerance and rightist extremism.

Worse still, this might remain the case if Brexit depresses growth. When people are confronted with evidence that they are wrong, they often don���t simply change their minds but become more entrenched in their views. As Tim Harford says, facts don���t necessarily change people���s minds. If we get Brexit, lower migration and weak growth, many voters won���t infer that Brexit is to blame. Instead, they���ll blame ���elites��� for mismanaging Brexit, and will demand even-tougher migration controls.

In this context, I regard the albeit slim chance of a Labour election victory with only tempered delight. My fear is that if it fails to stimulate growth sufficiently to offset the effect of Brexit or just on-going capitalist stagnation it, as well as migrants, will suffer the nasty backlash.

May 26, 2017

May's groupthink

I don���t think commentators have drawn the right inferences from the mess May made over social care policy.

The problem is not that she made a U-turn: if you���re heading in the wrong direction, a U-turn is a good idea. Instead, the episode reveals a fundamental failure in how May makes policy.

The Times reports that ���few were asked in advance��� about the dementia tax, and says the secrecy of May���s inner circle ���has become notorious���. The FT reports a ���senior Tory��� as saying that the policy ���wasn���t really run by anyone outside the inner circle.��� And the Guardian says:

Conservative insiders under [Nick] Timothy and [Fiona] Hill talk of a disciplined atmosphere and often highly pressurised blame culture, where people from advisers to ministers fear receiving a dressing-down for stepping out of line or veering off script.

All this suggests to me three related errors. One is taking a decision in haste. Sam Blainey writes:

The social care proposals were, apparently, a last-minute addition placed there at the behest of Nick Timothy, the Prime Minister���s powerful joint chief of staff. But this means they will not have been stress tested to destruction. Consulting with your colleagues may be tiresome and dull, but an hour-long meeting to discuss some of the Tory plans would have allowed them to address and hammer out any problems.

Secondly, there is what the FT describes as a ���disdain��� for the advice of some ���experts.��� However, if you need a quick decision the natural thing to do is to adopt the proposal of someone who has gathered evidence and thought long and hard about the issue, as Andrew Dilnot has. Believing that one���s own snap judgment is better than his is an example of egregious over-confidence.

Thirdly, tight-knit groups lack the cognitive diversity to take good decisions; nobody in May���s inner-circle seems to have stood up to Timothy���s suggestion. As Iain Martin says, ���Team May is way too narrow in its composition.��� The FT quotes Lord Ricketts, former head of the Foreign Office:

Surely one of the lessons learned from this is that you can���t do this in tight secret groups without consultation and without talking to political colleagues.

In short, what we have is an example of groupthink. Irving Janis wrote:

The advantages of having decisions made by groups are often lost because of psychological pressures that arise when members work closely together, share the same values, and above all face a crisis situation in which everyone is subjected to stresses that generate a strong need for affiliation. In these circumstances, as conformity pressures begin to dominate, groupthink and the attendant deterioration of decision-making set in (Groupthink, p 12-13)

From this perspective, I find it hard to excuse May���s conduct. Politics is an activity is which some errors are inevitable: social affairs are complex processes which are often unmanageable and unpredictable; all large organizations such as government departments by their very nature contain some dysfunctionality; and there are what Harold Macmillan called ���events, dear boy.��� Faced with this, Prime Ministers should at least not add to these unavoidable errors by making avoidable ones. They should learn from history and from research into cognitive biases.

And this is what May hasn���t done: Janis wrote Groupthink way back in 1982. Anyone who aspires to be in a position to take decisions should know it. Yet May seems not to. She failed to avoid errors which were well-known to anybody who knew anything about the history and psychology of decision-making.

Mistakes I can forgive. Illiteracy and ignorance, however, are another matter.

You might think I���m making a partisan point here. I���m not so sure. May has done what Blair did when he went to war in Iraq: he too ignored well-known principles of good decision-making.

This alerts us to the possibility that our political system does not adequately weed out irrationalities. Last year, I wrote:

Chilcot���poses a systemic question: how can we ensure that political structures favour rational decision-making? This question will, of course, be ignored.

That looks like a rare correct prediction. And it���ll remain the case until the media and voters understand leadership better. ���Strong��� leadership isn���t about delivering diktats from on high. It���s about taking good decisions, which often requires openness, diversity and being awake to cognitive biases. It���s not clear that May can do this. And this is not entirely her personal fault.

May 25, 2017

Poverty, ambition & reference levels

I���ve written before about how inequality perpetuates itself through differences in confidence: people from rich backgrounds have the chutzpah to blag good jobs for which they are unqualified, whilst those from poorer backgrounds have confidence knocked out of them. However, a new paper by David Chivers suggests there���s another mechanism which can have the same effect ��� differences in aspirations.

He shows that people who are just above the poverty line are scared to take risks for fear of falling into poverty. This traps them into low-paying but safeish jobs. By contrast, risks are taken either by the rich, who can afford them, or the desperately poor who have nothing to lose.

Although Dr Chivers applies this to decisions on whether to become entrepreneurs in poorer countries, it resonates with me. Once I realized that I could pay the leccy bill and was in no danger of becoming homeless, all ambition left me. Rather than seek new, possibly better jobs and risk them not working out, I focused on keeping the safe job I had.

The analogy with Dr Chivers��� work lies in the importance of reference levels of income. For Dr Chivers, the reference level is absolute poverty. For me, it was the income we had as kids. As Malmendier and Nagel (among others) have shown (pdf), experiences in our formative years influence our economic choices years later.

This poses the question: how common am I? In one sense, of course, I���m not: there aren���t many that go from child poverty into Oxford. What I���m speculating is that those that do might be disproportionately likely to end up in middling careers. Having achieved a lowish reference level of income, we pootle along not chasing directorships or partnerships. We leave that to richer people who have higher reference levels: I suspect that a major spur to ambition is the desire to keep up with one���s father.

This isn���t to say we opt out of the rat race entirely: our fear of poverty stops us downshifting. It���s posh people who feel they can afford to take risks who give up work to become artisanal jam-makers.

As I say, this is speculation. It���s possible ��� and true for a few ��� that growing up poor can give a man a longlasting ambition to prove himself to the rich. But I suspect that for most of us anger can���t last a lifetime. Two factoids support my suspicion.

One Is the common claim that young professional footballers lack the drive to get to the top of their profession because they have too much to young. Having an income above the reference level set by one���s childhood saps ambition.

The other comes from research by Henrik Cronqvist and colleagues. They show that people who grew up poor but who invest in the stock market later in life buy stocks on lower price-earnings ratios. This is consistent with child poverty making people risk averse (though in this case the aversion to risk pays off!)

All this is consistent with a bigger fact ��� that more egalitarian societies have higher social mobility. There are many possible reasons for this, not least being that it���s easier to climb a ladder if the rungs are close together. One extra mechanism, though, might be that more equal societies give people from poor homes a higher reference level of income, which prolongs their ambition.

It���s also consistent with the fact that child poverty leaves lifelong scars ��� literally so.

If I���m right, the case for abolishing child poverty is even stronger than appreciated, because child poverty might hold back economic growth even years later by dampening ambition and entrepreneurship.

Now, I stress that I speculating here, And I know there are dangers in generalizing from one���s own case (at least in mine: doing so is fine for everybody else). But there is surely a question here. And because political discourse is dominated by people from posh backgrounds, it���s a question that doesn���t get the attention it should.

Chris Dillow's Blog

- Chris Dillow's profile

- 2 followers