Chris Dillow's Blog, page 56

August 6, 2017

Choice in economics

The other day, I woke up thinking I fancied toast for breakfast rather than my usual muesli. I got up, got dressed, put the kettle on���and got myself a bowl of muesli. Force of habit overcame my conscious choice.

I mention this because of a post by Jason Smith, in which he questions economists��� assumption that people make deliberate choices. ���I do not think humans are "really thinking" about many of their economic choices��� he writes. My breakfast was an example of that.

Now, I don���t want to get into high-falutin��� grand theory here. Instead, I���ll just suggest four things that might support Jason���s scepticism.

One is that a lot of our economic behaviour is like my breakfast ��� a matter of habit. Most of us are shat, showered, shaved and in the office before we���ve thought about it. We can waste half our lives this way. Our everyday labour supply ���decisions��� are to this extent unconscious. We���re more like unthinking automata than deliberate choosers.

So too is much of our consumer behaviour. Millions of us stick with the same banks, utilities and insurance companies out of habit, at least until a threshold of dissatisfaction is breached.

Savings behaviour also fits this pattern. Much of this takes the form of a monthly direct debit into a pension or Isa. And rightly so. It���s easier to get into satisficing habits than it is to make optimal ad hoc decisions. As Alfred North Whitehead said, ���civilization advances by extending the number of important operations which we can perform without thinking about them.���

Secondly, the feasible set might be so small that there���s not much to choose from. Granted, even the poor can choose between Lidl and the pound shop ��� and perhaps have to make more deliberate choices between them than we richer people with our weekly Ocado habit. But they don���t really have a choice about how much to save. And many of us don���t have much choice of job (because of high job-specific human capital, not just loose labour markets). Nor do we have much choice of how much to work: it���s 40 hours a week or zero for many.

I suspect it���s no accident that the idea of economics as the study of individual choice only fully emerged in the late 19th century ��� because before then, economic behaviour was mostly a matter of habit and tradition rather than choice. Peasants got up, worked the land and went to bed not because they chose to do so but because that���s just what they did for generations. Yes, things have changed since then. But by how much?

Thirdly, Maynard Keynes asserted that firms can have little knowledge of the future ��� a claim corroborated by Rosewell and Ormerod. This suggests we should think of entrepreneurship and investment projects not so much as conscious choices ��� and certainly not optimizing ones ��� but as a form of evolution in which the market selects (imperfectly) for randomish mutations. Maybe it���s only the hindsight bias that causes us to impute skill to successful businessmen.

Blind natural selection doesn���t just operate upon corporate strategies. Hayek argued that market economies and property rights also emerged via this process:

Rules generally tend to be selected, via competition, on the basis of their human survival value. (The Fatal Conceit, p20)

You wouldn���t describe an ant colony as being the product of the conscious, deliberate, maximizing choice of individual ants. Why, then, try to describe complex emergent human societies in this way?

Fourthly, our economic behaviour and beliefs are shaped by the past ��� even the distant past. For example, American attitudes today (inequality (pdf), right-wing racist (pdf) whites and black ���underclass culture���) is in part the product of 19th century slavery ��� as is African under-development. To take another example, areas of western Europe that were conquered by Napoleon enjoyed faster economic growth decades later, in part because of the institutional changes he imposed. Or to take another example, the fact that the same dominate elites over centuries in different societies points to a persistence in inequality that���s hard to reconcile with the idea that choice and agency determine our fates.

To all this we must add that our high incomes in the west are due not to our own actions but to centuries of growth. I���m one of the 1% of richest people who ever lived. Perhaps nine-tenths of this is due to having been born in the right place and time. To attribute this to my choice and agency would be a self-serving lie.

You might reply to all this that there mere fact that incentives matter suffices to establish agency. I���m not sure. Sunflowers turn to face the sun. They behave as if they are responding to incentives. But they have no agency.

I don���t think that in saying all this I���m saying there���s no role for choice; for that view, try Daniel Wegner���s The Illusion of Conscious Will. Nor am I saying that microfoundations never matter. Instead, when we ask ���why did he do that?��� we must look beyond ���max U��� stories about mythical individuals abstracted from society and look at the role of habit, cultural persistence and constraints. As someone once said, ���men make their own history, but they do not make it as they please.���

August 3, 2017

Fiscal policy with a flat Phillips curve

It���s widely agreed that the Phillips curve is flat, that low unemployment is not stoking up wage inflation ��� though perhaps this has been true for longer than thought. This poses the question: what are the policy implications of this?

Simon says there���s a danger of the Bank raising interest rates too soon ��� because looking at unemployment and the output gap points to a risk of inflation which isn���t in fact there.

But I suspect it also has implications for fiscal policy.

I���m thinking here of the concept of the structural budget deficit. This is an estimate of how much the government would borrow if the output gap were zero. Conventional wisdom says that the bigger is this structural deficit, the more likely we are to need to tighten fiscal policy. One reason for this is that if the output gap is zero the economy is unlikely to grow quickly, so we can���t rely upon growth to narrow the deficit. Also, at a zero output gap interest rates might need to rise soon to prevent inflation rising, which would raise borrowing costs. Tighter fiscal policy would both obviate the need for much higher rates, and would make debt more sustainable if borrowing costs do rise.

This matters because the OBR believes that the deficit now is largely structural. Its latest Economic and Fiscal Outlook says:

With little sign of either spare capacity or overheating in the economy, we judge that the structural deficit (which excludes the effects of the economic cycle) is close to the headline deficit at 2.6 per cent of GDP. (Par 1.21)

But what if the output gap tells us nothing about future growth or inflation? (It doesn���t matter whether this is because the concept has always been wrong or because the link between ���full employment��� and inflation has changed). The need for a fiscal tightening then diminishes. If inflation doesn���t rise, government borrowing costs needn���t rise. And the economy is as likely to continue growing as it ever was, thus perhaps generating tax revenues.

The idea of a structural budget deficit makes sense to the extent that it���s sensible to think of inflation being caused by a negative output gap and its correlate full employment. If, however, the output gap and unemployment rate are uninformative for future growth or inflation, then the idea of a structural budget deficit doesn���t mean much. It should not then be used to justify fiscal tightening.

Of course, there might be other justifications ��� though I suspect these are weak at the zero bound and when real gilt yields are negative. All I���m saying is that if we���re throwing away the idea of the output gap, and if the Phillips curve stays flat, then we should also chuck out the notion of a structural deficit.

August 2, 2017

Tories vs the 21st century

It���s become a clich�� that the Tories want to return to the 1950s, before the age of mass migration and our entanglement with the EU. These, however, are not the only examples of Tories discomfort with the modern world. Tom Welsh says the Tory party is threatened by the large number of university graduates, and Amber Rudd seems befuddled by the internet.

This poses the question: why are the Tories so unhappy with the 21st century?

It hasn���t always been so. Cameron and Osborne, despite being lamentably incompetent, at least seemed comfortable in today���s world ��� and not just financially. And whilst Thatcher spoke of Victorian values, her project was also one of modernizing the economy, at least by her own lights. Toryism has not always been a nostalgic yearning for the past.

In fact, to we relics of the 1980s, there���s something especially paradoxical about the ascendancy of reaction among Tories. I remember Cold Warriors celebrating Karl Popper���s vision of an open society: Thatcher called The Open Society and its Enemies a ���marvellous book.��� In some respects, though, we now have such an open society: migration; gender fluidity; less deference; and peer-to-peer communication which bypasses traditional hierarchies. And many Tories hate it.

Why? Here are two theories.

First, the 21st century hasn���t delivered what the Tories hoped. They had hoped that the defeat of trades unions, privatization, cuts to top taxes, deregulation and fiscal austerity would unleash a dynamic, productive economy. It hasn���t.

This means we need to rethink the relationship between markets, hierarchies and the state ��� which means, of course, rethinking not just social democracy but Toryism too. May���s talk of the need for an industrial strategy was a dim recognition of this. But the Tories (perhaps temporarily, perhaps not) lack the intellectual resources for this task. Thatcher could invoke Friedman, Hayek, Popper and the architects of public choice theory. Who has May got?

I suspect one reason for the popularity of Brexit on the right is that, having vanquished unions and red tape, the EU is pretty much the only scapegoat they have left for the UK���s disappointing economic performance.

Secondly, and perhaps relatedly, the Tory base is breaking up.

One aspect of this is that the always uneasy coalition between business and social conservatives looks less tenable today than ever: the Brexit supported by old reactionaries is against the interest of finance and much of business. Today's Tories thus have a more precarious client base.

A second aspect is that the decline of property ownership and degradation of erstwhile good jobs has eroded one source of support for the Tories. In the 80s, young urban professionals (yuppies) were Thatcherites. Their equivalents today are Corbynistas.

I know I might well be guilty of wishful thinking in saying this. But it could be that the Tories are so unhappy with the 21st century simply because it offers them nothing but the refutation of their beliefs and decline in their power.

July 31, 2017

Reinventing the wheel

In both the UK and US, wage inflation has stayed low despite apparently low unemployment ��� to the puzzlement of believers in the Philips curve. Felix Martin in the FT says there's a reason for this. The ���dirty secret of economics,��� he says, is ���the central importance of power.��� Inflation, he says, is ���society���s default method of reconciling, at least for a while, irreconcilable demands.��� And because workers don't have the power to make big demands, we haven���t got serious inflation.

What's depressing about this isn���t just that it���s right, but that it needs saying at all.

Economists of my age were raised to see that inflation was a matter of power. The very idea of the Nairu arose from a paper (pdf) written by Bob Rowthorn in 1977 (He didn���t actually coin the phrase ���Nairu���, but the idea is there). ���Conflict over the distribution of income affects the general level of prices in advanced capitalist economies��� he wrote. ���Power plays a central role in the determination of wages and prices.���

His insight was taken up. In a textbook that grew from some of the few lectures I actually attended in the mid-80s, Wendy Carlin and David Soskice wrote:

In an economy in which both workers and firms have market power���each group will attempt to get hold of particular share of the economy���s product���Suppose that the competing claims are inconsistent ie that the claims of workers to real wages and firms to real profits sum to more than is available in output per head. The each side will attempt to secure its claim by using its market power ��� workers will secure higher money wages and firms will put their prices up. The result is rising inflation. (Macroeconomics and the Wage Bargain, p6)

In this view, the Nairu is the unemployment rate necessary to secure peace in ���the battle of the mark-ups*���.

Anyone who knows anything about the genealogy of the Nairu would therefore know that insofar as it is a useful idea at all, power is indeed central to it.

And yet Felix has a point; this fact has been glossed over by later fancier theories. This is yet another example of something I���ve said before ��� that technocrats have a blindspot about power.

But there���s another point here. This shows why the history of economic thought matters. It���s because the creators of economic thought sometimes had ideas which subsequent thinkers ignored. Intellectual progress is not guaranteed.

The tendency of some new Keynesians to ignore the role of power in determining inflation is just one example of this.

Another example is the IS-LM model. Among its faults, this contrived to efface what was perhaps Keynes most important point ��� that our knowledge of the future ���is usually very slight and often negligible.���

A recent paper (pdf) by Oscar Valdes Viera gives another example. Neoclassical economists who tried to ���construct economic laws that would validate the existing capitalist order as universal, natural, and harmonious��� led us away from Adam Smith���s insights that people are social beings motivated by more than mere egotistic self-interest. If economists had more accurately followed Smith rather than be misled by ideological motivations or mathematical elegance, they wouldn���t have needed to rediscover the importance of institutions and complex (pdf) motivations (pdf).

I don���t write all this to decry mathematical economics: I think it has a (limited) role. Instead, I���m appealing for economists to be a little more aware of the history of their discipline. Doing so can save us from having to reinvent the wheel.

* I'm not sure who coined this phrase: it might have been Richard Layard and Steve Nickell.

July 28, 2017

Brexit: an interminable debate?

David Aaronovitch has a nice piece in the Times on the stories that Trumpites and Brexiters can tell themselves to avoid admitting being wrong*. I���d add another problem ��� that the ratio of noise to signal is so high that firm evidence is hard to find.

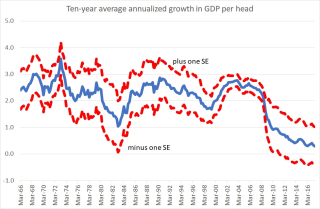

Let���s take GDP per head. Remainers claim that this will be lower under Brexit. NIESR estimates that Brexit will cut GDP by up to 7.8% by 2030, and CEP economists (pdf) by up to 9.5 per cent.

But trend growth is noisy, even over longish periods. For example, in the last ten years the standard deviation of annual growth has been 2.3 percentage points. This implies that even over ten years the standard error of annualized growth has been 0.7 percentage points.

The intuition here is simple. If we take any time period, it���s possible that it contains a disproportionate number of good years. It would be wrong to infer from this that trend growth is high: what���s really happened is that we got lucky. Conversely, if our sample contains some bad years, trend growth will look low when in fact we���ve been unlucky.

Even over periods as long as ten years, luck by no means cancels out.

My chart shows the point. It shows that it���s possible that trend growth didn���t change much from around 2% from the 70s through to the late 90s.

And here���s the problem. Even the worst-case costs of Brexit aren���t much bigger than one standard error. CEP���s estimate of a 9.5% hit is equivalent to 0.9% lower average growth over the 11 years from 2019 to 2030. That���s only 1.3 standard errors. Which is the sort of thing we could get through bad luck.

Or it might be cancelled out by good luck. It���s possible that growth will be higher in the 2020s simply because Brexit is one of only many influences upon growth. Maybe the scarring effect on animal spirits of the financial crisis fade. Maybe we'll get more sensible macroeconomic policies. Maybe the slowdown in world trade will be reversed. Or perhaps some new innovations will boost investment. There are many possibilities.

If this happens then even if the CEP���s worst case scenario is bang right, Brexiters will be able to say in (say) 2030: ���you said Brexit would hurt growth, but in fact the economy���s done as well in the last 10 years as it did in the previous 10. You were wrong.��� Remainers will reply that things would have been even better had we stayed in the EU. Ex hypothesi, they���d be wholly correct. But this won���t be clear from the facts.

My point here is that it���s quite possible that the economic impact of Brexit won���t be proven, at least sufficiently clearly to persuade Brexiters. This isn���t just because of our reluctance to admit we were wrong. It���s also because a combination of the Duhem-Quine problem and a high noise-signal ratio means that the debate might, in practice. be intractable. I find this a depressing prospect.

* Scoffers have pointed out that Aaronovitch has himself used such epistemic defence mechanisms in his continued support of the Iraq war. I think that just shows we are all much better at spotting cognitive biases in others than we are in ourselves.

July 27, 2017

Trade deal? Yawn.

One of the most elementary distinctions in economics (and in life) is that between instruments and objectives. Interest rates, for example, are only an instrument whereas the objectives are price and output stability. I fear, though, that this distinction is being overlooked by those Brexiters aroused by what Trump calls a ���big and exciting��� trade deal between the UK and US. Trade deals are only a means of achieving what really matters ��� prosperity. And they might be a weak one at that.

Liam Fox claims that bilateral US-UK trade could rise from ��167bn a year to about ��207bn by 2030 ���if we���re able to remove the barriers to trade that we have���. This isn���t as impressive as it seems.

The UK currently exports ��100.3bn of goods and services to the US. Let���s assume this rises as much as Fox claims. Over the 11 years from 2019 to 2030 that���s a rise of ��24bn. Which is 1.2% of GDP. Or 0.1% per year. And in fact, the rise would be much less than this simply because exports have a high import content*.

Granted, this might understate the benefit. Perhaps a trade deal would boost GDP not so much by raising exports but by giving us access to cheaper imports, thus raising real incomes. However, cheaper US imports would threaten to drive some UK producers out of the market ��� a fact they would of course resist. One reason why trade deals take such an infernally long time is simply that every goddamn lobbyist in the country sticks their neck in.

All this, though, assumes something that mightn���t be the case ��� that Fox is right that a trade deal would raise exports a lot: that word ���if��� in his statement is doing a lot of work.

Research by Monique Ebell and Silvia Nenci shows that this mightn���t be the case. Nenci, for example, shows that cutting tariffs has been of only ���small significance��� in boosting trade. A big reason for this is that trade deals often leave in place non-tariff barriers to trade such as differences in regulations. These are the sort of things removed not by trade deals but by a single market across nations. If only somebody had ever thought of such a thing.

What���s more, there are countless non-governmental obstacles (pdf) to trade such as exchange rate volatility, consumers��� preferences (pdf) for home-produced goods and services, uncertainty, credit constraints, a lack of entrepreneurial nous and of course distance. Two big facts tell us that these are important. One is that world trade has slowed in recent years without significant increases in legal obstacles. The other is that Germany exports much more than the UK does to non-EU countries ��� a fact which tells us that the barriers to UK exports are not primarily regulatory.

Herein lies my gripe with Brexit. It steals cognitive bandwidth. Instead of considering the countless possible ways** in which we might improve our economic performance without the omniuncertainty of Brexit, we���re discussing how to clean a fucking chicken.

Why, then, are Brexiters making such a big thing of a UK-US trade deal? One reason lies in the old clich�� that if your only tool is a hammer, everything looks like a nail. They���re making the mistake the right has made for years ��� of assuming that dynamism and flexibility will be unleashed if only the state gets out of the way.

Also, there���s the confusion of instruments and objectives. Those who regard Brexit as a good thing in itself are making a fetish of trade deals: they're saying ���look at what we can achieve outside the EU��� without asking what the payoff to that will be.

In this sense, Brexiters are like the worst sort of amateur DIYers who refuse to hire proper tradesmen. Their unwarranted belief in their competence and self-reliance is causing them to wreck the house.

* This is a specific example of the general policy made by Dietz Vollrath ��� that ���you can���t reform your way to rapid growth.���

** There is of course a tension between this claim and Vollrath���s scepticism about supply-side reform. My point is that economic stagnation requires a broad-spectrum response; we should throw as many sensible policies at it as possible, in the hope that one or two will work.

July 26, 2017

Marriage & wages

Actor Tom Chambers has caused a row by claiming that ���many men's salaries aren't just for them, it's for their wife and children, too." As a justification for the gender pay gap, this is lousy. But there���s a core of truth in what he says.

It���s a lousy justification because if employers paid higher wages to people with dependents we���d expect to see women with children earn more than childless ones. But the opposite is the case. TUC research (pdf) has found that full-time working mothers aged 42 earn 7% less than otherwise similar but childless women. That might be because mothers take time off work to care for their babies and so accumulate less experience. But it also seems to be the case that single mothers earn less than married ones ��� which is inconsistent with Chambers��� ���breadwinner hypothesis.���

However, he���s got a point in another sense. Fathers and married men do, on average, earn far more than single men or those without children. The TUC has estimated that fathers earn more than 20% more than otherwise similar men without children. And Elena Bardasi and Mark Taylor have found (pdf) that married men on average earn 46% more than the never-married.

These are massive differences. The question is: why?

One reason is selection effects: some men only get married or have children if they can afford to do so.

Another big explanation is simply that married men are different from single ones, and so would get higher pay any way. The things that make men good marriage prospects also make them attractive to employers ��� such as good education or dependability. Bardasi and Taylor write:

A large proportion of the marriage premium is due to unobservable characteristics that are valued both by wives and by employers, such as motivation, loyalty, dependability and determination.

We should add to this list appearances. Handsome men earn more than munters (pdf) on average (though there are of course exceptions: Piers Morgan, for example, earns a fortune).

However, these things don't explain all of the married men���s wage premium. Bardasi and Taylor say that married men earn more than singletons because marriage increases their productivity. They point out that the wage premium is higher for men whose wives do more household chores. Maybe, therefore, married men earn more simply because they���re not as worn out as us singletons from having to do the housework.

The problem with this, though, is that it doesn���t observe productivity directly. Naomi Feldman and Francesca Cornaglia address (pdf) this problem by studying professional baseball players, whose productivity can be measured directly. They find that married players on average aren���t individually better than single ones, but they do earn more. One reason for this, they say, is that married players are more consistent, and this enhances team performance. Also, they say, married players are less exploited; wives help players to drive harder bargains (perhaps in part by reminding them of their team-mates pay).

For me, this chimes true. I would have thought that marriage and children would increase men���s earnings by making them more dependable: married men are less likely to spend their evenings drinking and gambling and so are more likely to be fresh in the morning. As baseball manager Casey Stengel said, ���Being with a woman all night never hurt no professional baseball player. It's staying up all night looking for a woman that does him in."

There is, though, another potential effect of marriage which I would expect to be important in some cases. I suspect that if I���d ever been married I would have earned more because I would have changed jobs. I���d have chosen higher-paid but riskier or less interesting jobs than the one I���ve had. I���d have chosen a bundle of compensating advantages in which money featured more highly. This, however, doesn���t seem to be a significant factor in the research, which surprises me.

There are two points to all this. One is that, if we strip away the moralizing, Chambers has an empirical point. The other is that there are countless things that determine wages, as a classic paper (pdf) by Bowles Gintis and Osborne pointed out. One of these things is bargaining power.

July 25, 2017

In defence of the state pension

���Should we pension off the state pension?��� asks Robert Colville. The answer is: emphatically no. Quite the opposite. There���s a case for increasing it.

Robert is right that the cost of the state pension will rise over time. The OBR expects it to rise from 5.3% of GDP now to 7.3% in 2060 if the triple lock continues.

But this is irrelevant. Unless we euthanize people in their 60s, we���ll have to pay pensioners an income. The question is whether this comes from taxes in the case of a state pension or from dividends in the case of a private pension financed by stock market investment. Whichever it is, there���s a burden upon future working people.

And I reckon there���s a good case for pension provision to be done by the state more than via individual private pensions.

I don���t say this merely because some people are too short-sighted or poor to save, important though this is. It���s because even the most prudent saver will struggle to provide a private pension for herself.

One reason for this is that the costs of private pensions are eye-wateringly high. It���s common for fund managers to charge ��1500 a year on a ��100,000 pension pot - which is a fortune for what should be a simple administrative job.

But there���s a bigger reason. It���s impossible to know how much we should save. This isn���t just because we don���t know how long we���ll live or because stock market returns are volatile. It���s also because we don���t even know what long-run equity returns should be.

Of course, we know they���ve been high in the past: 5.7 per cent per year in real terms since 1900. But we can���t be at all sure this is relevant. For much of the 20th century, investors feared there was a chance of something really nasty happening: military defeat, nuclear annihilation, revolution or severe depression. For the most part, these risks didn���t materialize and so returns were good, at least in the US and UK. But we can���t be sure that our luck will continue, and it���s not obvious that stock markets now are so under-priced as to offer decent long-run returns.

In fact, if we add the equity premium (pdf) estimated by Mehra and Prescott to current real bond yields, we get negative prospective real returns on equities.

I suspect this is too pessimistic. But that���s not my point. The point is that we cannot know how much we can save for a pension. And remember ��� the costs of misjudging savings cut both ways. Under-saving gives us an impoverished retirement. But over-saving means we deprive ourselves of nice experiences in our youth, and so have a depleted stock of happy memories in our old age.

A good state pension is the solution here. The state is better able to bear risk than private citizens.

This isn���t just because tax revenue is more predictable than equity returns. It���s also because the state can better pool some risks. For example, whilst individuals face longevity risk (the danger of outliving our assets) this is not so troubling for the state; aggregate life expectancy isn���t so uncertain as individual life expectancy.

And there are some types of equity risk the state can bear. Retired savers face distribution risk: the danger that profits and dividends will fall as wages rise. This isn���t a problem for governments which can tax labour as well as capital. Equity investors also face creative destruction risk ��� the danger that future growth will come from as-yet unlisted companies rather than from listed ones (as happened in the 70s (pdf)): insuring against this risk by holding private equity funds is difficult, as these expose us to considerable fund manager risk. But again, this needn���t trouble the state as it can tax profitable firms whether they are listed or not.

You might question how much fiscal space governments have. But they have a damned sight more than individuals do.

For me, all this argues for the state undertaking the job of pension provision far more than it does. This isn���t to say there���s no place for private provision: insofar as doing so involves investing overseas, we can get future pension incomes from foreign workers not just UK ones, which is sensible risk-pooling.

I suspect there are simple reasons why this case is rarely made. One is that people tend to fetishize the public finances, and forget that some jobs need to be done and the question is only how to pay for them. Another, of course, is that low state pensions suit the parasitical fund management industry very well ��� and it has considerable influence over politicians and journalists.

There is, though, another point here. Given that future pensions must be paid by future workers, it is imperative that they produce a pie big enough to feed future oldsters as well as themselves. This means that policies to increase productivity are essential not least as a way of better providing future pensions.

July 22, 2017

The ideology of "the market"

One curiosity of the row over top BBC pay has been the attempts of past and present BBC bosses to defend high pay by invoking ���the market���. ���There is a market for Jeremy Vines, there is a market for John Humphrys��� says James Purnell. ���We operate in a market place.��� Pay is based on a ���market-based calculation��� say Mark Damazer (9��� in). ���The BBC does not exist in a market on its own where it can set the market rates.If we are to give the public what they want, then we have to pay for those great presenters and stars" says Lord Hall.

However, the ���market��� here is a queer one. There aren���t many firms who want to hire someone to read the ten o���clock news, and there aren���t many who can supply the proven skills to do so. It���s a thin market. In such a market, we should understand pay as being set by a bargaining process in which power is exercised on both sides.

Talk of the ���market��� is therefore what Georg Lukacs called reification ��� the process whereby ���a relation between people takes on the character of a thing and thus acquires a ���phantom objectivity.������ It obfuscates the fact that wages are set by the power of one person over another. Such obfuscation serves a profoundly ideological function; it effaces the fact that the capitalist economy is based upon power relationships.

Of course, BBC presenters aren���t unusual here. It���s generally the case that the labour ���market��� is in fact a power relationship.

For example, (many) capitalists have bargaining power and (many) workers do not. This means that, generally speaking, capitalists exploit labour.

And the ���market��� has given us a relative decline in low-skilled pay since the 1980s. This isn���t wholly due to technical developments but to changes in power, such as the decline of trades-unions and welfare state and adoptions of surveillance technologies that have reduced the efficiency wage element of their pay.

Similarly, ���market forces��� have given us stagnating real wages over the last ten years. But again talk of the ���market��� disguises what are in fact dysfunctional emergent features of capitalism ��� the stagnant labour productivity that has arisen from, among other things, low innovation and capital spending.

What���s more, ���demand��� is in part an ideological construct. Bosses are well-paid in part because of an ideological belief in the transformative power of leadership ��� a belief that isn���t wholly backed by facts. And carers and cleaners are poorly paid because of an ideology which devalues their work.

Talk of ���the market��� is often question-begging; it begs the question of how, exactly, prices and wages are determined in the market. The answer usually involves some element of power.

Now, Hall, Damazer and Purnell are not stupid men and they probably fancy themselves ��� not perhaps wholly without justification - as among the more liberal and humane members of the ruling cadre. And yet they guilty of an unreflecting inability to see that market relationships are also power relationships. In this of course, they are not unusual. I���ve long complained that centrists and ���liberals��� have a blindspot about power; we saw just this in this week���s Taylor report for example.

This blindspot, of course, serves the interests of the rich well. The BBC is not impartial.

July 21, 2017

Cronyism, & the demand for redistribution

Is actually-existing capitalism a fair or a rigged game? The answer matters a lot for attitudes towards redistribution, as some recent experiments by Matthias Sutter and colleagues show.

They got people to choose between a safe investment and a risky one. After the pay-off to the risky investment was seen, they asked third parties whether they wanted to redistribute.

When the pay-off to the risky asset was determined fairly ��� by the toss of a coin ��� few people were complete egalitarians. However, they then tweaked the experiment so that subjects who chose the risky asset could toss the coin themselves and report the result without anybody checking it. In this experiment, the number of third parties who were egalitarians tripled.

Even the suspicion of cheating ��� let alone the reality ��� creates a big increase in demand for equality.

It���s in this context that we should read three things I���ve seen recently:

- A survey of CEO pay by Alex Edmans, Xavier Gabaix and Dirk Jenter finds that high pay cannot be entirely explained by maximizing of shareholder value, and that rent-seeking plays a part.

- Luigi Zingales argues (pdf) that corporate and political power are becoming increasingly intertwined, and this is a threat to the free market, prosperity and democracy.

- Graeme Archer calls on the government to fight the ���crony corporatism��� which has seen bosses��� pay soar without any increase in economic efficiency.

What we have here are mainstream and rightist writers acknowledging that the game is rigged, at least partly. Rhetoric about capitalism is changing. Even outside the left, the rich are no longer seen (only) as talented public beneficiaries whose rewards are the product of free markets, but also as thieves who exploit power for their own ends.

Sutter���s experiments suggest this should cause a big rise in demand for redistribution. We don���t need to prove that theft and rent-seeking are widespread; the mere suspicion of it creates many more egalitarians.

But there���s a quirk here. Sutter���s experiments also found that even where there is that suspicion of cheating, many people remain libertarians who refuse any redistribution. This isn���t wholly unreasonable. They might judge that the danger of stealing money from the honest risk-taker outweighs the desire to punish cheats. Or ��� to translate Sutter���s results into the real world ��� they might not want to deter beneficial risk-seeking entrepreneurship.

Professor Sutter and colleagues infer from this that the suspicion of cheating creates political polarization.

I draw another inference. It���s that we need much more than redistributive taxation to tackle cronyism. We need to change institutions to prevent rent-seeking. Whether Archer���s relatively mild suggestions ��� more transparency and shareholder power ��� are sufficient is something I very much doubt.

Chris Dillow's Blog

- Chris Dillow's profile

- 2 followers