Chris Dillow's Blog, page 55

August 22, 2017

Willing the ends but not the means

There���s a link between two of my recent posts which I���d like to bring out. It���s that actually-existing centrists and rightists make a mistake of willing the ends but not the means.

For example, centrists rightly want us to remain in the EU. Many, however, fail to appreciate that the vote to leave was strengthened by economic conditions which they helped to create. Austerity ��� in which the Lib Dems colluded ��� and capitalist stagnation (of which some have been insufficiently attentive) generated hostility to immigration, antipathy to elites and a desire for change.

Likewise, centrists and the right want an open, tolerant society but fail to see that stagnation creates closed-mindedness and intolerance.

Let���s take another example. Robert Halfon says Conservatism means ���giving everyone a chance to climb.��� But he doesn���t seem to realize that actually-existing capitalism militates against this. Inequality reduces social mobility (pdf): this is the message of the ���Great Gatsby curve���. This is partly because it���s harder to climb a ladder when the rungs are further apart, and also because the rich give their children opportunities and connections which are denied to others. And on top of this, job polarization further reduces mobility, simply by removing rungs from the ladder.

Here���s another example. Whilst rightists profess a love of freedom, they fail to appreciate that capitalism can retard it. This isn���t just because capitalists impose oppressive working conditions upon millions of people. It���s also because policies that would create real freedom ��� such as a basic income or jobs guarantee ��� might undermine capitalism by giving people the freedom to reject bad pay and conditions.

I���d add that competitive markets are incompatible with actually-existing capitalism. One reason for this is that capitalism tends to degenerate into cronyism as big business buys politicians. On top of this, technical change seems to have made capitalism less competitive than it used to be.

There���s a common theme here. It���s that actually-existing capitalism nowadays thwarts the values that centre-rightists profess to have: toleration, openness, opportunity, freedom and competitive markets.

They���ll reply to this that capitalism has done wonders to create prosperity, and in doing so has created real freedom and civilized values.

They are absolutely correct. However, to take for granted that capitalism will continue to do so is to commit the fallacy of induction. Marx claimed that:

At a certain stage of development, the material productive forces of society come into conflict with the existing relations of production���From forms of development of the productive forces these relations turn into their fetters.

It may be that this is now true of capitalist relations of production. If so, we need much more critical thinking about capitalism, and reform thereof (to put it mildly) if we are to promote the values of centrists and rightist. Such thinking, however, is absent especially on the right. Insofar as it takes an interest in economics, it is in the fantasies of Patrick Minford rather than in analysis of the real economy.

It���s for this reason that I say they will the ends but not the means.

August 21, 2017

A better centrism

Several readers have complained about my criticism of centrism. ���Your idea of centrism is not mine��� they say.

To which I say: now you know how I feel when rightists claim that centrally planned economies discredit socialism; they are attacking a conception of socialism which isn���t mine.

I therefore sympathize with those offended centrists. In both cases, we have the same problem. Just as actually-existing socialism doesn���t discredit other notions of socialism, so the flaws in actually-existing centrism don���t discredit other conceptions of centrism.

So, what are these conceptions? Some I���ve seen on Twitter look like silly self-serving assertions that would fail any ideological Turing test - such as the claim that centrists base their views on evidence rather than ideology, for example on the question of how far markets work.

But pretty much everybody claims to base their views upon evidence. The difference between me and actually-existing centrists consists in which evidence we prioritize. For me, the load-bearing facts are that actually-existing capitalism give us too much inequality, oppression and stagnation. For actually-existing centrists such as Labour���s centre-left, the facts have been that the far left has been unelectable.

Equally, there has been too much of a tendency to define centrism by what it���s not rather than by what it is ��� that it is neither left not right. But as Nick Barlow says, this means it���s ���a phrase that���s effectively meaningless, a political buzzword.���

For me, a better centrism would be based upon four principles:

- Cosmopolitanism Centrists should want an open economy with freeish immigration. Support for Brexit stems from this.

- Social liberalism.

- Rawls��� difference principle ��� in particular that inequalities are tolerable only to the extent that they are ���to the greatest benefit of the least advantaged members of society.��� This, I suspect would distinguish centrists from ���neoliberals��� who in Sam Bowman���s perhaps elastic conception of the term only ���care about the poor.���

- Devolving power. One attractive feature of some radical centrism (and part of the Liberal tradition) is the desire to decentralize. Strengthening local government, attacking corporate monopolies and encouraging coops are all features of this. Perhaps it���s this principle that most sharply distinguishes better centrists from actually-existing centrists of New Labour and the Lib Dems in government.

I would hope that the centrists who took umbrage at my piece would subscribe to these principles.

Which poses the question. Why, then, am I not a centrist?

Partly, the difference is an empirical matter ��� of how far inequalities actually do benefit the worst off: I suspect they don���t very much. Also, I suspect that centrists don���t sufficiently appreciate the extent to which capitalism and class divisions are barriers to these principles ��� for example, that capitalist stagnation creates intolerance.

But perhaps there���s something else. Maybe the difference between me and centrists is tribal one. My cultural referents are leftist ones: I���m happy to sing the Red Flag and even Internationale. My intellectual influences are less Keynes and more Kalecki, Bowles, Roemer and Elster. And perhaps above all, my working class background ��� retained in my accent ��� puts a barrier between me and even the most generous centrists. These differences aren���t wholly rational. But as Hume said, ���reason is, and ought only to be, the slave of the passions.��� He might have added that anybody who thinks this isn���t true of them is kidding themselves. My response to centrists who claim to be pure evidence-based pragmatists is the same as Dylan's response to the accuation, "Judas!": I don't believe you.

August 19, 2017

On zero-sum thinking

One reason to welcome Steve Bannon���s departure from the White House is that it represents a setback for zero-sum thinking.

His idea that the US is at ���economic war��� with China embodies an us vs them mentality: what���s good for China is bad for the US and vice versa. To put it mildly, this is only one way of thinking. We might instead see the rise of China as good for everyone. In the long-run, a billion more prosperous consumers is a big market for the west. And before, then, what���s so bad about a supply of cheap goods? Globalization is not (pdf) to blame for stagnant US wages.

Bannon���s view is, in a sense, atavistic. It harks back to the mercantilist view that trade surpluses and the accumulation of gold were the aim of economic policy. Such a view was zero-sum: more gold for us meant less for them.

It also echoes the view of Thucydides view ��� reinvented recently as the ���Thucydides trap��� - that the rise of one state is a threat to another:

What made war inevitable was the growth of Athenian power and the fear which this caused in Sparta.

Bannon, of course, isn���t so exceptional here. Talk of an economic war appeals to millions of Americans, it chimes with Trump���s view that the world is split into winners and losers, and it perhaps also echoes the mentality that gave us Brexit: the EU is seen as something ���they��� impose on ���us��� rather than as a means of cooperating with our neighbours for mutual advantage. One reason, I suspect, for the popularity of Game of Thrones is that its depiction of a brutal zero-sum world speaks to the zeitgeist.

Such a view was, of course, rejected by Adam Smith, who pointed out that trade was mutually beneficial ��� a positive-sum game. It probably no accident that it was only after this discovery that mankind escaped the Malthusian trap: for pretty much all of human history until around the 18th century incomes per head stagnated (pdf), but they have soared since.

Which poses the question. Why have we seen a recrudescence of a discredited and harmful economic ideology? Why have Bannon���s simplistic ���us vs them��� thoughts been so popular?

The answer, I think, lies in a fact which Marx saw more clearly than most ��� that capitalism contains both positive- and zero-sum elements. On the one hand, it has given ���an immense development to commerce���, but on the other hand it does so by exploiting workers.

When capitalism is growing well the positive-sum elements are most salient and celebrated. When it stagnates, however, the zero-sum aspects become clearer. If the pie isn���t growing, a bigger slice for somebody else means a smaller slice for us. Stagnation thus makes us mean-spirited, regarding others as threats rather than opportunities. And as Phil says, because so many define others through the prism of ethnicity and gender, we get racism and sexism.

It���s surely no accident that the zero-sum mentality has strengthened since the financial crisis. How we live shapes how we think. And we live in zero-sum times.

Most decent people, from across the political spectrum, rightly decry Bannonesque talk of economic war. What many insufficiently appreciate, however, is that the appeal of such talk is rooted in a material failure of capitalism. Until this failure is removed, there���s little hope of more enlightened thinking. Bannon the man might have lost some power, but I fear his baleful influence will continue.

August 17, 2017

Centrism: the problem, not the solution

There���s talk, much of sceptical, of the formation of a new centre party. For me, this misses the point ��� that centrists are the problem, not the solution.

Owen Jones is bang right to say:

It is the economic order centrists defend that produced the insecurity and stagnation which, in turn, laid the foundations for both the ascendancy of the left and its antithesis, the xenophobic right.

This is true in two senses.

First, centrists contributed to the financial crisis by under-estimating the fragility of the system. They over-estimated market rationality. As Martin Sandbu says, the lie of capitalism is that ���market values of financial and other assets accurately reflect the economic value they represent.��� They also failed to appreciate that top-down management unconstrained by effective oversight is dangerous: the banking crisis wasn���t just a market failure but also an organizational failure.

If that was an error of omission which is clearer with hindsight than it was at the time, centrists��� second error is less forgivable: fiscal austerity. The Lib Dems supported this in government, and Labour���s centre-right failed to oppose it vigorously enough.

These two errors have had disastrous effects. They have given us a decade of stagnant real wages. Not only is this terrible in itself, but it also led to Brexit. Stagnation bred discontent with the existing order and hence a demand for some sort of change, and also had the effect history told us it would ��� of increasing antipathy towards immigrants.

In this context, centrists made a third error. With a few exceptions, such as the heroic Jonathan Portes, they failed to make a robust case for immigration: remember Labour���s shameful ���controls on immigration��� mug? This might be no accident. Blaming immigrants for poor public services and low wages helped to deflect blame from where it really lies ��� with austerity, crisis and capitalist stagnation.

Centrists are right to oppose Brexit. What they don���t appreciate, however, is that they themselves helped to create the conditions which led to the vote to leave.

I don���t think these were idiosyncratic failures of individual politicians. I suspect instead they arose from three systemic failures of centrism:-

- Insufficient scepticism about capitalism. Centrists have failed to appreciate sufficiently that actually-existing capitalism has led to inequality, rent-seeking and stagnation. New Labour���s deference to bosses fuelled their presumption that banks were in good hands and didn���t need to be on a tight leash.

- A blindness to the importance of inequalities of power. Centrists take it for granted that elites should be in control, even if they lack the capacity to be so. This left them vulnerable to Vote Leave���s slogan, ���take back control.���

- Excessive deference to the media. Centrists were for years obsessed with a form of ���electability��� which consisted in accommodating themselves to media lies about austerity and immigration.

In these senses, then, centrists��� failure has been a structural one.

Which poses the question: why, then, does centrism seem so appealing?

I suspect the answer lies in the failure to appreciate the distinction between extremism and fanaticism. Centrism���s intuitive appeal lies in the tendency to associate it with the virtues of moderation and empiricism.

Such an association, however, is at least partly unwarranted. In failing to appreciate sufficiently the flaws in capitalist hierarchy, centrists are being ideologues more than empiricists.

August 16, 2017

Job polarization

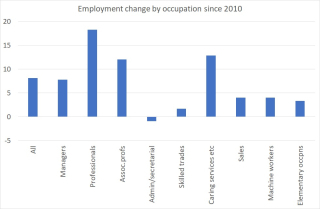

Today���s labour market figures show that we���re seeing job polarization ��� a relative decline of middling jobs.

My chart shows the point. It shows changes in employment by occupation since 2010, when employment troughed*. You can see there���s been a fall in the number of administrative and secretarial jobs, and stagnation in the number of skilled tradespeople, but increase in the number of professional and ���associate professional��� jobs, and in the number of care workers. These trends would look stronger if we looked at changes in the last ten years; in this time, the number of skilled tradespeople has fallen.

Looking at wages, there���s a more complicated picture. The clearest story here since the trough of the recession has been the relative rise in managerial pay. This isn���t simply because this is more cyclical than other pay: their wages matched average pay during the 2007-10 downturn. What is perhaps cyclical, though, is the wages of skilled trades. These have outstripped average pay, but this doesn���t recoup their fall in relative wages during the recession.

Despite rising demand and rises in the minimum wage the pay of care workers has declined relative to the average, perhaps because of an abundant supply.

We���ve also seen a relative decline in secretarial pay, which is consistent with declining demand for the occupation.

However, professional and associate professional pay has declined in relative terms. This is consistent with such jobs being less good than they used to be. Or maybe there���s an element of job rebadging here: previously humble occupations have been renamed, dragging average pay down. Or perhaps what we���ve seen is demand for such occupations respond to a decline in relative price.

A big question here is: what does this mean for social change generally? I���d suggest (tentatively) two things.

One is that all this is ambiguous for equality.

One the one hand, there���s an equalizing tendency here. A couple comprising a skilled tradesman and a secretary would have an above-average household income. But the gap between them and the worst-off has fallen, because of their declining relative pay.

But on the other hand, these changes are increasing inequality not just by raising managerial pay but also by encouraging assortative mating. Once upon a time, well-paid men married their modestly paid secretaries, and this tended to equalize household incomes. Today, there are fewer secretaries to marry. The equivalently placed man is therefore more likely to marry a wellish-paid female. And this exacerbates household inequality.

Perhaps, though, there���s something else. These changes might justify the expansion of universities. Job opportunities for diligent but non-academic people ��� secretarial and craft work ��� have declined. Such folk need therefore to go to university to have a chance of a good job. Having a degree doesn���t guarantee getting such a job. But it increases your odds.

There is, though, a more general point here. You don���t have to believe in economic determinism to think that the labour market shapes our culture, with perhaps longish lags. It���s plausible, therefore, that these occupational changes will lead to cultural change perhaps of sorts which we cannot yet predict. It���s not at all clear to me that these changes will be wholly welcome.

* The numbers aren���t seasonally adjusted, so I���m comparing 2017Q2 with 2010Q2.

August 15, 2017

The behavioural economics paradox

People aren���t as daft as some behavioural economists would have us believe. This is the message of a new paper by Olivier Bargain and colleagues. They studied the choices of British workers of how long to work, and found that:

People behave on average as if they were maximizing SWB���A majority of individuals actually make decisions that are in line with the maximization of income-leisure satisfaction.

Of course, there are exceptions to this. But many of these are because people are constrained by labour market institutions and policies: some people work too much because they can���t find decent part-time work, and others too little because they can���t find work at all.

Granted, there���s a caveat here. Perhaps people���s preferences have adapted to their circumstances and prior choices. Nevertheless, this is evidence that people aren���t as stupid as paternalists claim. Perhaps workers are badly off not so much because they make bad choices, but more because they are the victims of inequality and bad policies.

Bargain���s finding is consistent with some other evidence. For example, Marc Fleurbaey and Hannes Schwandt found that only a minority of Americans could think of easy changes to their lives that would increase their subjective well-being ��� which is what we���d expect if most people were maximizing their well-being. And people���s spending decisions do seem rational and forward-looking on average, in the important sense that ratios of consumer spending to wealth predict subsequent stock market and economic fluctuations.

How can we reconcile all this with the claim that voters are ill-informed and irrational?

Easy.

Our spending and working decisions are made regularly, so we can learn from experience to make better ones. And we have a strong incentive to do so: if we���re wrong we end up poor and unhappy.

In voting, however, neither of these conditions is met. Even general elections are one-off events (let alone referenda) so we don���t get the relevant feedback that would help us make better decisions in future. And we���ve little incentive to do so; if I make a stupid decision in the voting booth, I���ll not suffer.

This brings me a paradox about behavioural economics, at least as it is used in politics. It invites us to distrust people when they should be trusted ��� when they make regular decisions about their everyday lives. But it trusts people when they should be distrusted ��� for example by deferring too much to unfiltered and unreflective public opinion*.

Downing Street���s ���nudge unit��� should have worried less about the irrationalities of consumers, and more about the reckless overconfidence of David Cameron which gave us austerity and Brexit.

* There���s a stronger case for worker democracy than there is for referendums.

August 14, 2017

The social mobility lie

Sonia Sodha writes:

if we care about social mobility, then we should care about reducing assortative mating.

To which Tim Worstall replies that this requires serious infringements of freedom.

I agree with Tim. Social mobility is the enemy of freedom. Enforcing it would require governments to prevent parents from doing their best for their children to stop them falling below the glass floor, and it would prevent firms from hiring whom they wanted.

It seems, then, that we have a conflict of values.

Except we don���t, because there���s nothing valuable about social mobility.

A simple thought experiment tells us this. Imagine a dictatorial society split into three classes - slave labour, guards, and rich and powerful oligarchs - in which children of the slaves have good chances of entering the higher classes either through education or perhaps lottery. We���d then have social mobility. But the society would nevertheless be unfree and unjust. Social mobility, then, is no sign of a good society.

In fact, there���s something downright dishonest about it. Social mobility pretends that if people from poor homes do well at school and work hard then they can escape their class. But they can���t. Four facts tell us this.

One is that people from poor homes are more likely to die early, even if they get a decent job later in life. In Status Syndrome Michael Marmot writes:

Where you come from does matter for your health���Family background, measured as parents��� education and father���s social class, are related to risk of heart disease.

A second piece of evidence comes from a study of Swedish stock market investors. Henrik Cronqvist and colleagues show that people whose parents were poor are less likely to hold growth stocks than people from richer backgrounds, even if they have the same current wealth. This doesn���t mean they make worse investment choices. (Quite the opposite ��� value stocks tend to beat growth stocks). But it does suggest that growing up poor makes you more anxious and less optimistic in later life. This chimes in with my experience.

Thirdly, people from working class backgrounds earn less than those from professional ones, even if they have similar jobs and qualifications. This might be because they have less access to social networks and good connections.

Fourthly, the IFS shows that men from poor homes are less likely to be married in later life, even controlling for their own incomes. This is consistent with a more general pattern for the upwardly mobile to be lonely. We no longer belong to the class we come from, but don���t fit in to the one we join ��� in part because that class is chock full of twats who were born on third base but who think they hit a triple. As the great Jason Isbell sings:

Tried to go to college but I didn���t belong. Everything I said was either funny or wrong.

The truth is, then, that we cannot overcome the harm done by a class society. Scars don't completely heal. Waffle about hard work, merit and mobility are lies which function to legitimate inequalities and to give the rich and powerful the illusion that they deserve their fortune. The left should think less about how to increase social mobility, and more about how to abolish class divisions.

August 11, 2017

Entrepreneurial Marxism

Carl Packman on Twitter has described my vision of socialism as ���entrepreneurial Marxism.��� I like that. Entrepreneurial Marxism is necessary, roughly compatible with Marx, and feasible.

Let���s start with the necessary. Here, we Marxists have a paradox. On the one hand, Marx thought that socialism required material abundance: it was the solution to Keynes��� problem (pdf) of what to do with our leisure time. As G.A.Cohen put it:

[Marx] thought that anything short of an abundance so complete that it removes all major conflicts of interests would guarantee continued social strife, "a struggle for necessities and all the old filthy business". It was because he was so uncompromisingly pessimistic about the social consequences of anything less than limitless abundance that Marx needed to be so optimistic about the possibility of that abundance (Self-ownership, Freedom and Equality, p10-11)

He thought capitalism would deliver such abundance: ���No social order is ever destroyed before all the productive forces for which it is sufficient have been developed.���

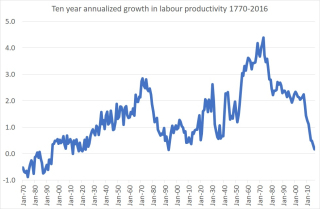

This might, however, be too optimistic. Over the last ten years, productivity has almost stagnated ��� something we���ve not seen (except briefly in the 1880s) since the start of the industrial revolution. This suggests we���ll need a form of post-capitalism which delivers economic growth. Now, I���ll concede that a centrally planned economy might be good at generating growth in the sense of more of the same; it can deliver more pig-iron. But this isn���t the sort of growth we need now. As Gilles Saint-Paul points out (pdf), growth must come from an increased variety of products. Centrally planned economies are lousy at this. Decentralized entrepreneurship is better.

And such entrepreneurship isn���t wholly incompatible with Marx. To Marx, it is our human nature to work and produce:

In creating a world of objects by his personal activity, in his work upon inorganic nature, man proves himself a conscious species-being (Economic and Philosophic Manuscripts.)

It���s for this reason, largely, that he condemned capitalism. Capitalism, he thought, forced us to do meaningless drudge work under the domination of others, and thus alienated us from both our nature and each other. It���s for this reason that Jon Elster has written: ���Self-realization through creative work is the essence of Marx���s communism.��� (Making Sense of Marx, p521.)

It���s likely that, for some at least, this self-realization will take the form of working under one���s own steam. In fact, Marx saw this:

A being does not regard himself as independent unless he is his own master, and he is only his own master when he owes his existence to himself. (Economic and Philosophic Manuscripts, quoted by Erich Fromm)

Marxists have traditionally interpreted this as to mean that collective self-mastery is necessary, through democratic control of the means of production. That���s true enough. For some people, though, it might mean individual own-mastery ��� working for oneself.

But wouldn���t this entail the very exploitation of others that Marx hated?

Maybe not so much. Even under capitalism, the profits (and hence exploitation) from innovative activity are small. And the prospects for exploitation under post-capitalism might be less, to the extent that intellectual property laws would be less friendly to incumbents and because fulfilling work elsewhere would make it hard for entrepreneurs to attract labour without offering something decent.

But wouldn���t this kill off innovation and entrepreneurship? Not necessarily, and not simply because I suspect a lot of such activity arises from intrinsic motives such as the urge to create things and solve problems. It���s also because there���ll be offsetting stimuli to entrepreneurship. One is that higher aggregate demand would close the innovations gap. Another is that post-capitalism would ensure a high supply of finance, for example via a state investment bank. And a third is that lower rewards to rent-seeking would force some bosses out of cushy monopolies and bureaucracies and into entrepreneurship.

Of course, I appreciate that all this will be sneered at from both sides ��� from Marxists claiming (with some justification) that I���m being unfaithful to Marx, and from some rightists who can���t get their tiny minds around the possibility that there are economic models other than capitalism and central planning. But I don���t give a shit.

August 10, 2017

Game of Thrones & ethical misjudgments

Is Daenerys the real villain of Game of Thrones? asks Matt Miller.

Logically, he has a point; there was more than a grain of truth in Cersei���s denunciation of her. Her claim to the throne is founded on no more than her descent from a mad tyrant; she���s murdered hundreds of her opponents in cold blood; the Dothraki army is no respecter of human rights; her acquisition of titles betokens a dangerous narcissism; and she���s acquired weapons of mass destruction.

And yet I instinctively recoiled from Matt���s claim: noooo, not her. There are, I suspect, two reasons for this, which are in fact widespread.

One is the belief that our enemy���s enemy must be a goodie.

It might well be this sort of mistake that led many lefties to support the Venezuelan government: it���s antipathy to western neoliberalism was sufficient to win it support.

Not that the left is unique in this error. During the Cold War, the right supported (or at least tolerated) obnoxious regimes such as Pinochet and apartheid because these were anti-communist.

The underlying problem here is that we want the world to be divided between good (us, of course) and bad ��� and the wish is the father to the belief. We don���t want to acknowledge the truth that we are all more or less flawed and that we must all sometimes do bad things; it���s this reluctance that lies behind the hostility to Northumbria police���s no doubt difficult decision to pay a child rapist for information.

The second reason for not seeing Daenerys��� flaws is a halo effect.We want to believe that good qualities go together, so somebody that good-looking can���t be bad, surely? The New York Times has asked viewers to rate GoT characters along ugly-beautiful and good-evil axes ��� and most characters lie in the good-beautiful and ugly-evil quadrants*: Cersei is an outlier**.

Again, this is a common error. Cishet men���s reluctance to doubt Daenerys��� character is the same thing as women���s shock when Poldark raped Elizabeth.

Millions of people have been materially and emotionally damaged by over-estimating the correlation between looks and character. And it���s not just wishful thinking (���she���s the one���) that causes this. Juries seem to be softer upon attractive defendants than ugly ones. The magistrate who recently let off a model guilty of shoplifting perhaps wasn���t so atypical.

My point here should be a trivial one. Our ethical judgments, just like our judgments in politics and in investing, are clouded by countless possible cognitive biases. And yet people are so damned confident about them.

The link here cuts both ways. It could be that we don���t want to believe that evil people are good-looking; if Ramsey Bolton weren���t so horrible, he���d probably be rated as attractive.

** Maybe my sympathy for Matt's thesis is based in part upon Cersei's milfiness.

August 9, 2017

My socialism

Looking at critics of Venezuela makes me feel like intelligent religious believers when confronted with some new atheists: they���re attacking nothing I believe in. The shortcomings of the Chavez-Maduro government in no way whatsoever undermine my conception of socialism.

What is my conception? You might think I���m going to set out my blueprint of a socialist Utopia. You���d be missing the point. Capitalism was not the conscious design of a single mind, but rather it evolved. The same should be true for socialism.

For me, socialism is a system which fulfils, as far as possible, three principles.

One is real freedom. Oliver Kamm praises a liberal order as one in which ��� in contradistinction to state socialism - ���embraces value pluralism, in which citizens are free to pursue the goals that matter to them.��� I share this ideal, but I fear that capitalism does not sufficiently achieve it. Under capitalism, millions of us are compelled to work in often oppressive and coercive conditions. Our goals are thwarted. Perhaps Marx���s biggest gripe with capitalism was not its injustice but its alienation; the fact it prevents us from pursuing our goals.

In this context, a basic income is crucial. It would enable people to pursue their own lives. It would empower Cory Doctorow���s walkaways.

A second desiderata is voice. As Phil says, ���socialism involves a deeper, more thoroughgoing democratisation of social life.��� At the political level, this requires institutions of deliberative (pdf) democracy ��� not simply imbecile ���speak your branes��� referenda. At the economic level, it requires worker democracy.

One reason for this is that procedural utility matters: happiness requires not just good outcomes, but ways of reaching them that give people a say.

A second reason is that Hayek had a point: knowledge is inherently dispersed and fragmentary and unavailable to a single mind. Centralized control is often inferior to decentralized aggregation methods. (As I���ve said, it is bosses who believe in central planning, not Marxists like me). It doesn���t follow from this that we need an unfettered free market ��� but it does follow that we should consider mechanisms for deploying the wisdom of crowds. Proper democracy is one such.

The third value is equality. I don���t mean here any particular Gini coefficient. Instead, what matters are two things.

One is how inequalities arise. I���ve no problem with some people getting rich if people freely reward them for good service ��� Nozick���s Wilt Chamberlain argument has no force for me ��� although luck egalitarianism justifies them paying some extra tax. For me, a socialist economy would be one in which inequalities due to exploitation, rent-seeking and rigged markets would be minimized. Actually-existing capitalism does not do this (pdf).

The other is their effects. Inequalities of income spill over into inequalities of respect and political power. To me, this is unacceptable. My socialism would accept Michael Walzer���s blocked exchanges (pdf) ��� ways of preventing inequalities in one sphere from spreading to others. Also, it���s plausible that current inequalities (of power, not just income) are a barrier to economic growth. An acceptable socialism would sweep these away.

What role would the state play in this?

I suspect it wouldn���t be a large one. We Marxists are wary of the state simply because it is often used for reactionary and repressive ends. A big state can be (and is) captured by capitalists. Nationalization, for example, cannot be sufficient for socialism simply because it can be reversed. Marxism is in some respects very different from social democracy.

Instead, a big role for the state is to facilitate the transition to socialism, by encouraging socialistic institutions. Some call this accelerationism, others interstitial (pdf) transformation. Again, a basic income is crucial here: it enables people to walk away from oppressive capitalism (if they choose) and into cooperative ventures or self-employment. Also, the state could help spread coops by encouraging public sector mutuals and using procurement policies to favour them and penalize hierarchical firms. Massive housebuilding also has a role: cutting the cost of housing would free people from the debt and rent bondage that compels them to submit to capitalism.

The general principle here is to empower people to reject exploitative capitalism (if they want). This would so squeeze profits that capitalists would have to transform into more egalitarian forms or die. (The state is, of course, needed to smooth this process).

As for the place of markets in all this, it should be what it is now - a narrow technical matter: does this particular market work and if not can we make it do so? It���s perfectly possible ��� I think desireable ��� to have freeish markets without (pdf) capitalism.

Personally, my socialism would have a perhaps big role for entrepreneurship ��� just not the sort that rips people off.

It should be obvious to everyone that this vision of socialism is massively different from that of a centrally planned dictatorship.

Of course, this vision of socialism differs from many others���, though it should be compatible with many of them: I���d hope there���s a parallel between it and Robert Nozick���s framework for utopia.

What all this is definitely not, of course, is statism, nor the illiberalism of Maduro���s government. Maybe the tragedy of Venezuela brings Jeremy Corbyn���s judgment into question. But it tells us nothing about my sort of socialism.

Chris Dillow's Blog

- Chris Dillow's profile

- 2 followers