Chris Dillow's Blog, page 52

October 27, 2017

Structure vs character in politics

BBC1���s The Last Post depicts a group of mostly decent men upholding what many of you regard as an unjust system, of colonial rule. This illustrates an important and under-appreciated point - that the justice or not of social systems is not reducible to, or wholly explicable by, the character of its actors. Social structures are emergent. Or to put the point more trivially obviously, good men can do bad things, and bad ones good things.

To take just two of countless historical examples, Lyndon Johnson did more than most men to advance the cause of racial equality, despite using language that would today disqualify him from politics. And Otto von Bismarck did not create one of Europe���s first welfare states because he was a soft-hearted liberal*.

The classical economists saw this point clearly. Smith famously wrote that ���it is not from the benevolence of the butcher, the brewer, or the baker, that we expect our dinner, but from their regard to their own interest.��� And Marx wrote that the quality of working conditions ���does not, indeed, depend on the good or ill will of the individual capitalist.��� Smith thought markets caused greedy men to serve others. Marx thought they caused good men to exploit others. But both agreed that market outcomes weren���t reducible to individuals��� characters.

Instead, what matters are incentives and selection mechanisms. This is true not just of markets, but of organizations and political structures. If we have the right such mechanisms, then bad men can do good things. If we have the wrong ones, good ones will do bad things.

Which brings me to two more recent developments. Simon points out that Article 50 negotiations are going badly in part because the media did not facilitate a rational assessment of the UK���s bargaining position. This is an example of how political structures select (or at least filter) against good policy-making.

And then we have the fuss over Jared O���Mara. Phil makes a good point when he notes that words are not the only form of sexism and that in their actions the Tories are structurally sexist:

Who do they think suffer disproportionately from their Parliamentary votes to cut to social security, their cuts to the NHS, their real terms cuts to public sector wages?

This would be true even if each individual Tory MP were not personally sexist (which of course isn���t the case).

Now, there���s a danger here. It���s easy for Labour to downplay individual displays of sexism, homophobia or anti-Semitism in the belief that the party is structurally a force for equality. There might be an element of self-regard and wishful thinking here: organized labour has not, historically, been wholly untainted by sexism and racism.

Nevertheless, the point remains. We shouldn���t look only at individual politicians��� characters but at political structures. Do these promote justice (or efficiency or liberty) or impede it? Do they select for or against good conduct? Ideally, structures would be so selective of good behaviour that individual character would not matter at all.

In this sense, though, we have a paradox. Let���s suppose, arguendo, that Tories concerns about O���Mara���s language and conduct are sincere and well-founded in fact. What does this tell us about our political structures?

It says that MPs are not selected (by their parties and electorates) to be of good character. And it says that bad character matters because the incentives that MPs face do not rule out future poor conduct - that sexist boors have undue influence.

But this, of course, means that those Tories are making a leftist point ��� that our social and political structures do not select against sexism and homophobia and might instead help to sustain it. And they might well be right.

* One of the world���s first welfare states was created by Genghis Khan, which reinforces my point.

October 25, 2017

Capitalist triumphalism: a brief history

Ken Burns��� history of the Vietnam war is getting many plaudits. What���s not been noted about it, though, is that it reminds us of something we���ve forgotten ��� that the victory of capitalism over communism was not generally regarded as inevitable at the time. The idea that it was owes more to the hindsight bias than to historic fact. Indeed, capitalist triumphalism ��� of the sort we see from CapX, the IEA and Very Selective Reading of Wealth of Nations Institute ��� is relatively new.

What I mean is that the American government did not commit mass murder, sacrifice tens of thousands of its own young men, cause vicious domestic social divisions and jeopardise the economy in order to save Vietnam from a flawed economic experiment. It did so because it feared communism would succeed, not that it would fail ��� that communism could supplant capitalism. Equally, the Macarthyism of the early 50s was aimed not at rooting out cranks but genuine threats to American capitalism.

When Khrushchev spoke of ���burying��� and ���overtaking��� western capitalism, nobody laughed. The danger was a serious one. And the launch of Sputnik suggested to the world that Communism could produce technologies that eclipsed capitalist ones. As Francis Spufford showed in Red Plenty (discussed here and here) the Soviets had a genuine optimism that they could beat capitalism ��� and cold warriors feared they were right.

Yes Friedrich Hayek did warn that central planning was unsustainable. But he was regarded as a crank and outsider for most of the 50s and 60s. His was not the mainstream view.

In fact, fears for the viability of capitalism pre-dated the cold war. The classical economists all thought that capitalist growth would eventually cease. In 1848 ��� after decades of expansion ��� John Stuart Mill wrote:

The increase of wealth is not boundless: that at the end of what they term the progressive state lies the stationary state, that all progress in wealth is but a postponement of this, and that each step in advance is an approach to it.

(Marx���s view that a declining rate of profit would eventually cause the collapse of capitalism was, in essence, just a riff on Ricardo���s theory of diminishing returns.)

Yes, the classicals mostly approved of free markets. But they didn���t think growth was inevitable. They were free market pessimists. In this tradition, Joseph Schumpeter wrote in 1943:

Can capitalism survive? No. I do not think it can���[Capitalism���s} very success undermines the social institutions which protect it, and ���inevitably��� creates conditions in which it will not be able to live and which strongly point to socialism as the heir apparent���Prognosis does not imply anything about the desirability of the course of events that one predicts. If a doctor predicts that his patient will die presently, this does not mean that he desires it. One may hate socialism or at least look upon it with cool criticism, and yet foresee its advent. Many conservatives did and do. (Capitalism, Socialism and Democracy (pdf), p61-62)

On top of this, there was throughout the 19th and 20th centuries the constant fear of revolution. Bismarck���s creation of the welfare state in the 1880s was an attempt to buy off working class unrest: that retreat from pure free market capitalism would of course be followed across the west over the next few decades.

And of course, anybody in the 1930s, seeing that capitalism had produced catastrophic war, hyperinflation and then depression, could not have been at all assured of its desirability or viability.

Capitalism, then, like bull markets, has climbed a wall of worry. Confidence that it is the best way of achieving sustained increases in living standards is quite a new phenomenon. It dates from the 1980s. And given that productivity and real wages have stagnated in the last decade, justifiable belief in such a proposition was tenable for only around 20 years.

Why, then, is it so widespread? I���d offer two suggestions.

One is that our ideas are disproportionately influenced by our formative years. Many people in their 40s to 60s were deeply impressed by the collapse of social democracy in the 70s and of communism in the 80s, but are less influenced by the capitalist stagnation of the last decade.

The second is that the alternatives to actually-existing capitalism have for years lacked salience: I���m not sure how far Labour���s mild social democracy counts as a genuine threat to it. Yes, there are alternatives along the lines of participatory economics or market socialism for example. But these are sadly neglected. It���s easy to be a capitalist triumphalist if you think the only alternative is Soviet-style central planning, just as you can believe yourself fit if you compare yourself to a fat slob.

Yes, capitalism has seen off one rival. Whether it can see off all - and whether it deserves to - is an open question.

October 24, 2017

Brexit & risk attitudes

Simon Wren-Lewis points out a paradox ��� that on the one hand we have good evidence that older people tend to be more risk averse than younger ones, but on the other hand they supported the risky prospect that is Brexit. How can this be?

It���s not ��� or at least not wholly - because older people, being retired, are insulated from some of the costs of Brexit. People tend to vote ��� for the common good as they perceive it rather than their own narrow interest ��� and so older folk should have considered the interests of their children and grandchildren.

What���s more, there���s a good reason why older people should be more risk averse. They have learned ��� often at that most effective pedagogic establishment, the school of hard knocks ��� that big ambitions often fail. They should be more aware than most of our cognitive limits, not least because many older folk are so limited (pdf). They should be small-c conservatives, and hence Remainers.

So why weren���t they? Part of the answer, I suspect, lies in a paper (pdf) by Michael Woodford and colleagues. They point out that attitudes to risk are shaped by how we code (pdf) prospective wins and losses.

Take, for example, the question: how much would you pay for a 50-50 chance of winning ��1000? The expected value of the bet is ��500, but most of us would pay less because we���re risk averse.

Just how much we���d pay, though, depends on how we think about the win and the loss ��� how we code them. We ask: what could I do with ��1000? How much would the loss of (say) ��400 hurt? Differences in these codings generate differences in how much we���d pay ��� that is, differences in risk aversion.

This seems trivial. But it explains a lot. It explains why more intelligent people are more willing (pdf) to take on good bets. They can more clearly translate pay-offs into prospective mental well-being, whereas for others the coding is noisier and so they avoid such bets. It also helps explain why older folk are more risk averse: knowing their cognitive limits (and perhaps knowing that money doesn���t buy happiness) they avoid bets that others would take.

It also explains one element of prospect theory; the tendency to seek risks when you���ve lost money. We see the chance of ��1000 and think ���yay, I can get even��� and think of the loss as ���I���m in so much trouble already a little extra won���t make any difference.���

And it also explains why our attitudes to risk vary across domains: why we hold equities and buy insurance; why some avoid financial risk but play risky sports; and so on. It���s because the codiings differ from domain to domain.

Which brings me to Brexit. Brexit was not presented simply as a choice between a risky pay-off (Leave) and a safe one (Remain). Brexiteers also offered what they claimed to be intrinsic goods such as national self-determination. For various reasons ��� being brought up on 1950s war films, discomfort with immigration, whatever ��� these goods appealed more to oldsters than youngsters. And this appeal offset the tendency for oldsters to regard Brexit as risky.

In a sense, this is consistent with the coding view of risk aversion: oldsters saw Brexit as the offer of valuable intrinsic goods. They therefore coded it as a safe option. Youngsters, being less attracted to those goods, saw it as riskier.

I offer this only as a theory. But I think Simon���s point is sound: there is a paradox here that needs some sort of explanation, and this is the best I have.

Update/clarification. I intended this post to be more about the nature of risk aversion than about Brexit. It poses a radical question. If the same option can be coded as either relatively risky or relatively safe -as Brexit was/is - then does the concept of risk aversion apply at all? And if it doesn't apply here, might it be unhelpful in other real-world complex choices we face?

October 21, 2017

Why conservatives should be Corbynistas

Conservative values require socialist policies. That���s my reaction to this essay by Kevin Williamson. He bemoans the ���degraded state of the conservative movement��� for telling the poor that immigrants and elites are to blame for their hardship and neglecting the traditional conservative message that ���what is not necessarily your fault may yet be your problem, that you must act and bear responsibility for your actions.���

What Kevin fails to ask, though, is why is his conception of conservatism now out of favour?

In part, it was always an act of bad faith. In a hierarchical society somebody must be at the bottom of the heap. Sure, any individual might escape that fate by work, thrift and diligence. To believe that everybody can do so is, however, is to commit the fallacy of composition.

Also, even those who do escape need luck. I should be a poster boy for how you can escape poverty through work, study and savings: I grew up in a single-parent family hiding from the rentman behind the sofa to become a millionaire (just). Even this, though, needed luck: the luck of being perceived as intelligent; the luck of graduating in an age when well-paid jobs were expanding; and the luck of years of house price inflation. (No doubt posh cunts will poshplain why I���m wrong, but they can fuck right off).

What���s more, the scars of child poverty don���t heal. Those born poor are more likely to die young and be anxious and lonely than those born rich even if they do get good jobs.

The decline of traditional conservatism, though, might not be due simply to people waking up to reality. Instead, such conservatism has lost its economic base. I���ll concede that there was a time when the bourgeois values of study, hard work, ambition and thrift paid off ��� if only by giving you more chance of being exposed to good luck. But things have changed, for example:

- Job polarization means it���s harder for people without qualifications to achieve economic progress: some of the rungs of the jobs ladder are now missing. You can���t progress from the postroom to the boardroom now there are no postrooms, and working-class women can���t meet well-paid husbands in typing pools any more.

- If you get a degree and graduate job, you face more oppressive working conditions than we used to have: managerialism has eroded professional autonomy and so proletarianized what used to be the middle class.

- Younger people have no hope of buying a house, especially in London, unless they work in finance or have access to the bank of mum and dad. Even those who are otherwise upwardly mobile thus will remain propertyless.

- In an age of secular stagnation in which real interest rates are negative, there is no reward for thrift, even for the few who can save.

To put it bluntly, bourgeois virtues pay off in a bourgeois society ��� where there is a large middle class. But they don���t pay off in a 1% takes all society where wealth is accumulated in shadier ways.

Which brings me to my point. If conservatism is to escape its current ���degraded state��� then we need to (re-)create the conditions in which it is something more than a sick joke ��� conditions in which hard work and self-help pay. Such conditions include:

- Measures to increase pay, by improving workers��� bargaining power. Also, we need better jobs, which might require more government intervention to support technical progress.

- Improving the quality of work, which might require increased worker control. In truth, this shouldn���t be as radical as it seems. Back when work did pay for the ���middle class��� it did so because many of them became (meaningful) partners in law or accountancy firms.

- Policies to reduce house prices and so facilitate mass property ownership. This requires more than housebuilding. It requires a reversal of the financialization of the housing market.

- Measures to make thrift pay. This entails a looser fiscal policy, one effect of which would be to raise interest rates and the return on savings.

Traditional conservatives - those who support the virtues of self-help ��� should therefore be sympathetic to Corbyn because he, more than others, is offering to create the conditions in which those virtues will again pay off.

October 20, 2017

Why new centre parties will fail

For most of us, having an accident means losing our phone or spilling our drink. Jeremy Cliffe is cut from different cloth: he claims to have accidentally started a new political party. Being conceived by accident, however, does not in itself condemn one to failure ��� as millions of us can attest. What chance, then, does Radicals UK have?

Two things speak in its favour. One is that it will no doubt get lots of favourable media support from the many centrists who hate Corbyn. The other is that they are clean skins. The Lib Dems are discredited by the fact that they trebled tuition fees and collaborated with the economic illiteracy of austerity ��� which was of course a major cause of Brexit. Radicals UK will be untainted by such disgrace.

On the other hand, though, two more powerful forces are against it.

History warns us of these. Back in 1981 the SDP launched itself as a centrist party wanting to ���break the mould��� of British politics. The mould bent but didn���t break. Within nine years, most of the SDP was subsumed into the Lib Dems, and the rest were beaten in a by-election by the Raving Loonies.

One reason why the mould didn���t break is path dependency. Political parties are powerful brands that have been built up over decades. This loyalty doesn���t only attract millions of voters. It means that members stick with the party through thick and thin, even if they profoundly disagree with their policies and leaders. This gives them a resilience that a new centrist party won���t have. It also gives them an army of unpaid labour willing to deliver leaflets, get out the vote and speak up for the party in pubs and workplaces. Parties need bodies as well as heads.

Secondly, successful parties (unless perhaps they are nationalist ones) need some kind of class base and ��� given our electoral system ��� a geographically concentrated one at that. What would be the base of Radicals UK?

The party���s promises to be pro-EU and comfortable with both immigration and new technology suggests the obvious base would be younger metropolitan types who voted Remain. Many of these, though, are Corbynistas ��� attracted to Labour by its (apparent?) offer to end austerity, tax the ultra-rich and solve the housing crisis. What can Radicals UK do to prise them away?

A few weeks back, Jeremy made some suggestions. Whilst many strike me as reasonable (such as shifting taxes from income to land and inheritances) only one speaks to Corbynistas��� main concerns ��� the promise to build more houses. But I suspect that Labour could match that. Sure, it could mobilize discontent with Corbyn���s lack of support for EU membership. But grudges fade whilst interests do not. Corbyn���s huge appeal to the young declasse "middle-class" elements is founded on these interests. That gives Labour a class base that centrism will lack.

Yes, Radicals UK might appeal to less regressive elements of capital: firms wanting free migration and an open society. But there aren���t many votes in this.

All of which suggests to me an analogy. We already have a political party comprising decent people with reasonable policies and which speaks for around half the country: the Women���s Equality Party. And yet it is a nugatory electoral force. Why should Radicals UK be different?

October 17, 2017

On cutting house prices

Ian Mulheirn, echoing Kate Barker, writes:

It is very unlikely that the perennial wish of housing commentators to simply ���build more houses��� will make any meaningful dent in prices.

Many people think this is counter-intuitive, so I���ll try to explain why it���s not.

It���s because flows of supply are too small relative to the stock of housing to much affect prices. There are 23.7 million homes in England. In the 12 months to June, only 153,330 were completed. This means that even if annual housebuilding were to treble, we���d see a less than 2% annual increase in the housing stock.

There���s an analogy here with government bonds. Even before QE, government borrowing did not much affect bond prices. This was simply because the new supply of bonds was generally small relative to the existing stock.

It���s the same with houses. Houses are an asset, and the price of an asset depends upon the willingness and ability of people to hold the stock of it. Changes to the flow of the asset are generally too small to have much effect. For this reason, many economists have traditionally modeled house prices as if only demand matters; see for example this (pdf) or this (pdf).

This isn���t to say that increasing housing supply is a bad idea. It���s not at all. It���s just that it isn���t a magic bullet for solving the problem of affordability.

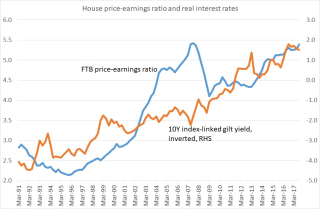

If supply doesn���t affect prices, what does? Lots of things: demographics (pdf), incomes, debt levels, expected incomes and the availability of credit. My chart shows another influence: real interest rates. The lower these are, the cheaper is the cost of credit and hence the higher are house prices. (Or if you want to be fancier, lower interest rates mean a higher net present value of future housing services and hence a higher house price.)

All this raises a puzzle: if high house prices are due to high demand, and if they are a problem (as I think they are on balance), what can be done to help young people buy them?

Obviously, some possibilities would do more overall harm than good. A recession would cut house prices, but it���s a lousy idea. I suspect the same would be true of tougher immigration controls. And other policies to help buyers would do no good because they���d be offset by price increases. Help to Buy, for example, seems to have pushed up prices. And I���d expect cuts to stamp duty to have a similar effect; yes, there���s a strong case for reforming property taxation but we shouldn���t hope it���ll much help first-time buyers.

That said, there are some demand-side policies that might reduce house prices, such as restrictions on owning second homes or housing as investments ��� in short, reversing the financialization of housing. Instinctively, I���m not over-keen on these; they would be abridgements of freedom. As ways of reducing house prices, however, they might be worth considering.

October 13, 2017

Why I'm not a lefty

Reading Christopher Snowdon���s attack on eco-miserabilists made me realize something ��� that in many ways I���m not a lefty.

This thing is, I agree with Snowdon. Ending economic growth does not move people up a higher spiritual plane. Quite the opposite. It makes them mean and nasty. Recession and austerity led to greater hostility to immigration and to Brexit.

Yes, there���s a case to suggest to people that they live more modestly, as a way of coping with capitalist stagnation. But there���s a world of difference between suggesting something and wanting to impose it upon them.

The point broadens. There is an element of preachiness in leftism which I dislike. Granted, many of those rightists who attack the liberal elite as ���patronizing bastards��� are narcissistic over-entitled posh white cunts. But what Joan Williams says of US Democrats applies perhaps in part to some of their British counterparts ��� they are smug and patronizing and out of touch with the working class. They are too quick to identify the ���white working class��� with backward attitudes, and too slow to see the genuine racism of the ruling class.

Equally, there is an element of lifestyle politics among some lefties ��� of wishing that everyone could be more like themselves. My big problem with ���nudge��� politics is that it assumes that rulers are rational and that the people are not ��� an assumption which is very questionable.

These are not the only ways in which I depart from many (some) on the left.

For example, I���m more accepting of markets than many are. The point is not that the private sector is inherently better at managing than the public sector. Instead, it���s that markets function ��� when they do so well ��� as selection devices, selecting for more efficient strategies and against less efficient ones. Back in the days when productivity was growing, a lot of that growth (pdf) came from entry and exit rather than from incumbent firms upping their game.

It���s for this reason that I���m not wholly unsympathetic to the introduction of markets into public services. Of course, outsourcing can and has been a way simply of channelling money to capitalists. And because children only get one chance of education, failed free school experiments can be costly. For me, though, the issue is more balanced than it is for many leftists. A lot hangs on precise institutional details rather than on general principles.

Also, I���m more sceptical than many lefties of higher corporation tax. I fear these aren���t an easy pot of money for government because they might instead lead to less investment, jobs cuts or relocation. I���m not wholly convinced by Paul Krugman���s arguments to the contrary because the UK probably has less monopoly power than the US and so fewer rents to tax and we���re a smaller more open economy so firms might relocate to Ireland or the EU. I don���t say this to oppose any increase at all, and certainly there���s a case for reforming corporate taxes. I just fear that a Labour government won���t be able to raise many billions this way.

A further difference between me and many other lefties is that I���m sceptical about higher minimum wages. Yes, I know their effects so far have been much less harmful than simple-minded free marketeers warned ��� though not perhaps wholly harmless. But it would be wrong to infer that further rises are risk-free; there���ll come a point when a wage floor will do more than merely capture monopsony rents. Just because you fell better after taking one paracetamol it doesn't follow that you should take 20 more. I would much rather raise real wages by increasing workers��� bargaining power via stronger trades unions, full employment, a jobs guarantee and citizens income.

There is, in fact, a common theme to all these differences. It's about attitudes to knowledge. I'm much more wary of how much we can know for sure and so am sceptical of policies which presume such knowledge. This might reflect a class difference: as someone of working class origin, I've had humility beaten into me in a way that posher lefties might have.

Unlike Nick, however, I���m not going to disown the left. The differences I���ve described are perhaps those between Marxists and non-Marxists. The non-Marxist left believes, with Orwell, that England is ���a family with the wrong members in control���. My problem is that in a class-divided society the wrong members will always be in control.

October 12, 2017

"Good policy, badly implemented"

A trend seems to be emerging among their advocates to describe both Brexit and Universal Credit as good policies badly implemented. For me, this raises a question: how big is the ���good policy, bad implementation��� set? I suspect it���s small, at least for major policies.

Take, for example, the biggest failures of post-war policy: Suez, Iraq, the poll tax, ERM membership. The fault with these is that they were bad ideas in principle. Few believe they���d have been redeemed by feasibly better implementation.

Yet another set of policies are those that are still controversial such as many of Thatcher���s reforms: weakening the trades unions, cutting taxes on the rich and privatization. Not even the most abject triangulator would argue that these were good ideas that were badly implemented. The debate is about the merits of them in principle.

So, what does fit into the set? Robert Harris suggested one possibility when he tweeted:

Brexiteers are sounding increasingly like Marxists: the theory is perfect, it just hasn't been implemented properly...

But I don���t think this works. Marxism is like liberalism or conservatism ��� a loose set of principles. The failure of a few Marxist governments does not discredit Marxism, any more than the failure of conservative or liberal governments discredits conservatism or liberalism. Of course, central economic planning is a bad policy. But it���s bad in principle; the problem is not that the USSR had the right idea but screwed up the implementation.

So what are we left with? There are contenders: numerous government IT projects, the Child Support Agency or individual learning accounts for example*.

All these are, however, second-line policies ��� the equivalent of squad players rather than stars. Nobody saw ILAs as their lifelong political project or identified emotionally with them in the way they do with Brexit. These tell us that bad administration is common ��� that there���s a great deal of ruin in a nation. Routine incompetence is commonplace ��� in fact, the norm.

I���m left, then, with my question: how many major, government-defining policies can we describe as good policies badly executed?

There���s a reason why there have been so few. It���s that implementation is policy. Policy-making is not like writing newspaper columns. It's all about the hard yards and grunt work of grinding through the detail. A failure of implementation is therefore often a sign that the detail hasn���t been thought through, which means the policy itself is badly conceived. Reality is complex, messy and hard to control or change. Failing to see this is not simply a matter of not grasping detail; it is to fundamentally misunderstand the world. If you are surprised that pigs don���t fly, it���s because you had mistaken ideas about the nature of pigs.

It is, therefore, often unacceptable to hide behind the ���good policy, badly implemented��� line. Bad implementation is at least sometimes a big clue that the policy was itself bad.

All this, though, raises another question. What about the mirror image of ���good policy, badly implemented���? It���s vanishingly rare that someone says of modern-day British politics that something was a terrible policy but beautifully implemented**. Why might this be?

* King and Crewe add tax credits to this list, but I���m not sure about that; given the trade-off between support for the poor and high withdrawal rates, and the difficulty of supporting people���s whose circumstances often change, administering the system was always going to be tricky. And I don���t think it���s been terribly bad given the scale of the challenge.

** I suspect that free marketeers could say this about the minimum wage, but I���m struggling to think of other examples.

October 11, 2017

The costs of suppression

The fall of Harvey Weinstein reminds me of an important phenomenon in the social sciences ��� that of preference falsification, as described by Timur Kuran.

Recall another despot, Nicolae Ceausescu. For years, he faced little dissent because people were afraid to speak out. Fearing that their friends or neighbours would shun them or denounce them to the secret police, Ceausescu���s critics kept quiet. They falsified their preferences. And because dissent was so rarely heard, others also kept their own hatred of Ceausescu to themselves. There was an equilibrium of silence: millions hated Ceausescu but kept quiet which incentivized others to keep quiet.

That equilibrium lasted for years, but it was brittle. When Ceausescu gave a speech on December 21st 1989 a few in the audience began to jeer. This emboldened others to express their true opinion and within days Ceausescu was dead.

There���s a parallel here with Weinstein. As the New Yorker says:

Previous attempts by many publications, including The New Yorker, to investigate and publish the story over the years fell short of the demands of journalistic evidence. Too few people were willing to speak, much less allow a reporter to use their names, and Weinstein and his associates used nondisclosure agreements, monetary payoffs, and legal threats to suppress these myriad stories.

As with Ceausescu, however, when one or two did finally call him out in public, others were emboldened to do so. And like Ceausescu his fall was swift after being so powerful for so long. When people suppress the truth, writes Kuran, ���deceptive stability and explosive change are thus two sides of a single coin.��� (Private Truths, Public Lies, p21)

One corollary of this is that persistence is not necessary a sign of sustainability or efficiency. Dysfunctional structures ��� Ceausescu���s tyranny or Weinstein���s domination of the film industry or Fred Goodwin's RBS ��� can persist not because they have hidden benefits or because their leaders are geniuses, but because of the brittle equilibrium of false preferences.

Something similar happens in financial markets. Just as people suppress their opposition to a tyrant because they believe others support him, so investors can suppress their doubts about an asset���s value if they see others buy it. In this way, bubbles can emerge ��� as we saw in tech stocks in the late 90s and credit derivatives in the mid-00s. And just as one or two voices of opposition to a tyrant can trigger an avalanche of opposition that brings him down, so can a few otherwise innocuous pieces of news trigger a crash. Information cascades work in both directions.

You might think that all this amounts to an argument for freedom of expression and cognitive diversity, of the sort expressed by John Stuart Mill or Nick Cohen. True. But it also reminds us that the enemies of that diversity don���t lie only in the state. The Weinstein affair reminds us that men in the private sector can also achieve power and wealth by suppressing freedom. And, in fact, self-censorship can also sustain inequality, inefficiency and injustice.

A clarification. I���m not of course trying here to tell the full story of Weinstein or Ceausescu. I���m simply highlighting one particular mechanism. The social sciences are, in essence, an inventory of mechanisms.

October 10, 2017

Centrists - become Marxists

Chris Leslie tweeted yesterday that ���Marxism should have no place in a modern Labour Party.��� You���d expect me to disagree, and I do. But I want to point out that a Marxist point of view might be an asset for non-Marxists within the party. I say so for three reasons.

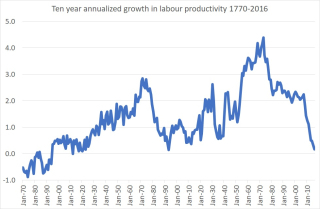

First, Marxism draws our attention to the fact that politics is shaped by an economic base ��� by the nature of capitalism. The things that centrists deplore such as Brexit and the rise of Corbynism are not (just) fits of stupidity. They are a response to a real economic fact ��� that a decade long stagnation in productivity (which is almost unprecedented since the start of the industrial revolution) has caused stagnation in real wages. This stagnation contributed to the insularity and anti-immigrant sentiment that gave us Brexit. And it has caused discontent with the established order and hence the rise in populism; when people feel as if they���re losing, they take a gamble on risky alternatives.

If centrists want to fight the rise of populism on the left and the right they must therefore offer an analysis of capitalist stagnation and solutions thereto.

Herein lies another use of Marxism. It reminds us that the state in capitalism must fulfil two functions: legitimation (keeping voters happy with capitalism); and accumulation (providing the conditions for growth). The most successful governments of the post-war period found albeit different ways of doing both: the Attlee, Thatcher and Blair governments. Corbyn is offering something along these lines. What counter-offer can the Labour right make?

Remember - Corbyn became Labour leader not so much because of his political genius but simply because his centrist opponents were offering nothing ��� neither diagnosis nor remedy for capitalism���s problems. If people like Leslie want to seriously challenge Momentum and Corbyn, they must answer the question posed by a Marxist point of view: is it possible to reconcile capitalism with popular needs and if so how?

There is, though, a third reason why centrists should adopt a Marxian point of view. It���s that Marxists understand class. For us, class is not a lifestyle choice ��� whether you have avocado toast or a full English. It���s about ownership. Capitalists own capital and workers do not, and this gives capitalists (some) power over both workers and the state.

This helps explain why Corbyn is so popular among the so-called ���middle classes���. It���s because they are not ���middle class��� at all. Their academic qualifications and decent incomes have not allowed them to escape drudge work or acquire property: if you want to understand why young people are Corbynistas, just look in an estate agent���s window. They are, objectively speaking and in Marxian terms, working class. And they are voting accordingly. If centrists are to effectively resist this, they need a class analysis and not just moralistic bleating.

Here, we must make two distinctions. One is between the Marxian diagnosis and the Marxian remedy. It is, I think, possible to use one but reject the other.

The second distinction is between temporarily adopting a perspective for particular purposes and being something. You can adopt a Marxist point of view without becoming a Marxist ��� just as I often become an orthodox macroeconomist, behavioural or financial economist depending upon the issue I face.

One of the most common forms of stupidity is the inability to have more than one point of view. If centrists are to become a serious political force again, they must stop equating who they are with what they believe, and take a Marxian perspective.

Chris Dillow's Blog

- Chris Dillow's profile

- 2 followers