Chris Dillow's Blog, page 60

May 21, 2017

Who benefits from Mayism?

Theresa May claims there���s no such thing as Mayism. I don���t know about that. What puzzles me, though, is that there don���t seem to be any obvious Mayites.

To see what I mean, contrast May and Thatcher. Thatcher had two things which May seems to lack.

One is an idea of how to increase economic growth: for Thatcher, this meant smashing trades unions, deregulation, lower taxes and restoring profits to encourage investment. Whatever its merits, this was at least a vision which had some intellectual backing and keen and articulate supporters.

May, by contrast, seems to offer no such thing. At least two of her policies ��� hard Brexit and immigration controls ��� would (if delivered) depress growth. And she has little idea of how to offset this. Her infrastructure plans offer nothing much that Labour isn���t, and her industrial strategy is weak. In contrast, to Thatcher, nobody is seriously suggesting May has a plan to restore growth.

Secondly, Thatcher���s policies certainly benefited large client groups: businessmen who enjoyed weaker unions; property owners who saw house prices soar thanks to credit deregulation; City boys who won from financialization and lower taxes; people who bought their council houses at a discount, and so on. Thatcher gave us yuppies, garagistes and Loadsamoney.

Where are the Mayite equivalents? Which groups are going to profit from a May government? Yes, peddlers of equity release schemes might profit from people���s need to buy social care; and immigration controls will encourage people smugglers. But these are probably too narrow a client base to be a successful electoral base.

Of course, May will defend the interests of a decent minority: she���ll protect the rich from Labour���s tax plans, and financiers from the transactions tax. But it���s not clear whose interests she���ll actively advance.

Here, we must distinguish between interests and preferences. May will probably satisfy the preferences of those who want a hard Brexit. But those preferences are intrinsic rather than a means to prosperity. It���s not obvious which significant social group will be made rich by this.

Hence my puzzle. I���ve long assumed that politicians serve particular material interests, yet it���s not obvious whose May is advancing.

You might reply here that the state in capitalist society has always had to fulfil two often contradictory functions: to ensure the continued accumulation of capital via ���business-friendly��� policies; and to legitimate the system by placating non-capitalists. Whereas Thatcher focused more upon the former, May���s ���red Toryism��� is focusing upon the latter. She���s promoting the interests of capital by buying off hostility to capitalism.

There���s some truth in this. But it misses two things. One is that popular discontent arises at least in part from the long stagnation of real wages. The other is that the current crisis of capitalism is not just one of legitimacy but accumulation: prolonged low investment tells us this. To both of these real problems, May is offering little solution.

This leads me to two possible different conclusions. One possibility is that Phil is right. The Tory party, he says, is ���decadent���: ���For decades, it has not been a suitable vehicle for the interests it's supposed to represent.��� It���s not clear that the Tories can remain popular in the long-term if they���re not offering a way of enriching some client base.

Perhaps, though, there���s something else. Maybe all this reflects the befuddlement of a Marxist who���s accustomed to thinking of politics in terms of material class interests, and yet the world has changed so that preferences matter more than interests and identities (such as somewheres vs anywheres) matter more than class. Whether these shifts are happening or not, and if they are whether they are long-lasting or not, are issues about which I am uncertain.

So yes, I���m puzzled.

May 19, 2017

The fairness error

In the Wheatsheaf last night, I was struck by an obvious injustice. The pub was charging everybody the same price for beer, regardless of their income. This is obviously unfair: why should the millionaire picking up his children from the posh school pay the same as a low-wage worker? Beer prices must be means-tested, so the rich pay more.

Astute readers might spot a problem with that paragraph. It���s bollocks. It would be grotesquely inefficient for barkeeps to check everybody���s income before serving their Tiger*. A far easier way of addressing this unfairness ��� if such it be ��� would be to tax the millionaire and give income support to the poorer customer. This would have the same effect as means-testing ��� the millionaire would be less able to buy beer and the poor person more able ��� but would be more efficient.

You might think this is childishly obvious. It should be. But it���s not. People are judging manifesto promises in the same bonkers way as I���m alleging beer prices to be unfair. Take three examples:

- Iain Martin says about social care: ���Someone aged 25 should pay masses more tax so someone with a ��1.5m house aged 75 gets free care? Really?���

- Giving a winter fuel allowances to all pensioners, rich and poor, seems unfair ��� hence Tory plans to means-test the payment.

- Labour���s plan to abolish tuition fees has been called a subsidy to (future) middle classes at the expense or poorer workers.

All these examples are of people making the same error I made with beer prices. They are expecting each individual transaction to be egalitarian and are overlooking the costs of doing so.

So for example, if you think it unfair that some rich folk get free social care, the solution is to tax them more: an inheritance or land tax would make sense for several reasons. The serious question is how to best pool the risk that some will need lots of social care and some not ��� a question the Tories haven���t addressed. If you think it unfair that rich pensioners get a winter fuel allowance, you should get them to pay higher income tax, not faff around with expensive and intrusive means-testing. And it posh people get subsidised by abolishing tuition fees, the answer is to get them to pay more income tax.

When it comes to judging inequality, what matters is the system as a whole, not individual actions. Expecting each individual policy to increase inequality would be inefficient, just like asking barkeeps to conduct means-tests. As Nicholas Barr says in a standard textbook on the welfare state:

It is frequently the overall system which is important...Taxation and expenditure should be considered together. (The Economics of the Welfare State, 2nd ed, p185, his emphasis)

Instead, the test of individual policies should be based in efficiency. Personally, I think winter fuel payments are daft: just have a higher state pension instead. Similarly, whether to impose tuition fees upon students is also a matter of efficiency: what���s the best way of financing universities? Do tuition fees (as I fear) have baleful effects upon the character of universities? And so on. These are genuine issues. What���s not a serious concern is that specific policies are inegalitarian. In the cases I���m considering here, equality concerns should be tackled by the overall tax and benefit system, not by each single policy in isolation.

* Other beers are available. But they���re not as good.

May 18, 2017

The end of competition?

For years, economists have believed that competition tends to equalize profits across firms, as inefficient firms either learn from better ones or go out of business, and as new firms enter markets and so compete away high profits. Several things, however, suggest that we need to change our mental model, because this basic common sense intuition might be wrong.

A few things I���ve seen recently point to this. Jason Furman and Peter Orszag say (pdf) "there has been a trend of increased dispersion of returns to capital across firms" in the US. David Autor and colleagues show that there has been a rise (pdf) of ���superstar firms��� earning very high profits. And Andy Haldane, echoing Bloom and Van Reenen (pdf), has said (pdf):

An upper tail of companies and countries has maintained high and rising levels of productivity. These productivity leaders are pulling ever-further away from the lower tail. Or, put differently, rates of technological diffusion from leaders to laggards have slowed, and perhaps even stalled, recently.

All this is the exact opposite of what we���d expect to see if competition equalized profits. So what���s going on? I suspect that here, as everywhere, there are no mono-causal explanations. A few possibilities are:

- Low interest rates and creditors��� forbearance mean that inefficient companies aren���t being killed off to the same extent they were in the 80s and 90s.

- Credit market imperfections prevent efficient firms starting or expanding (though this should be less of a problem now than a few years ago).

- Bad managers just can���t see how to up their game or exploit profit opportunities.

- Tough intellectual property laws impede firms from learning.

- Contrary to what Hayek thought, prices are not sufficient information. High prices don���t necessarily encourage firms to enter a market because they don���t tell us how long the profit opportunity from such prices will last.

- Many profitable companies operate in niches which are big enough to offer nice profits, but too small or too specialized to attract entrants: each week, the IC describes dozens of such firms.

- New technologies enjoy increasing returns to scale. As Stian Westlake and Jonathan Haskell say: ���Intangibles are often very scalable: once you���ve developed it, the Uber algorithm or the Starbucks brand can be scaled across any number of cities or coffee shops.��� This creates a winner-take-all effect.

- Network effects generate an incumbency advantage. If I set up a more efficient supermarket than Tesco, I should win enough business to get by, and to force Tesco���s prices down. But if I set up a potential rival to Facebook, I face a tougher job. Because the value of a networking site depends upon others using it, Facebook has a more entrenched advantage.

If all of this is right, and these are long-lasting changes ��� which is a big if ��� then we need to ditch some old mental models and rediscover some others. We should abandon the idea that competition equalizes profits and restrains monopolies and perhaps return to some older Marxian ideas.

Marx thought capitalism tended to generate monopolies. Some of his followers, most famously Baran and Sweezy, thought this would generate a tendency towards stagnation, as those monopolies generated more profits than they could spend.

For a long time, these ideas were mistaken. However, at a time when we���re seeing superstar firms build (pdf) up massive cash piles amid talk of secular stagnation, perhaps we need to rethink their relevance and implications.

May 17, 2017

When bad arguments work

Many of the most common arguments against Labour���s policies are laughably bad ��� such as the claim that people earning a little over ��80,000 a year will have to pay very much more tax; or the idea that higher top taxes wreck the economy; or the demand that individual spending plans be fully costed; or the notion that nationalization is a cost to the Exchequer.

In pointing this out, however, people like me are missing something important ��� that even lousy arguments have the power to persuade.

Robert Cialdini gives us an example of this in Influence. He tells of an experiment in which a woman tries to jump queues to use a photocopier in a university library. When she merely asked to jump in, 60% of people in the queue complied. But the question ���May I use the Xerox machine because I have to make some copies?��� got 93% to agree. Even a meaningless remark (why else would you want to use the copier?) elicited compliance.

What���s going on here is that the mere act of speaking has persuasive power. This has been corroborated by experiments (pdf) by Justin Rao and James Andreoni. They got people to play a dictator game in which one subject was given $10 and then invited to share some or none with somebody else. They found that in the straightforward game, dictators have an average of $1.53. However, when the third party asked for a share of the money, the dictator gave an average of $2.40. The actual wording of the requests didn���t seem to much matter. But say Andreoni and Rao, ���the existence of a request matters tremendously.��� They say:

Communication, especially the power of asking, greatly influences feelings of empathy and pro-social behavior.

The mere existence of messages, then, gets us to sympathize with the sender.

In this context, there���s a massive bias in the media. People earning over ��80,000 might be only 5% of the population, but they account for much more than 5% of communication. This leads us to sympathize with them. Add in the fact that people tend to believe lies, and we get a big bias towards the rich.

It���s often said that many people oppose higher taxes on top earners because they hope (mostly wrongly) to become one themselves. But this is only part of the story. We sympathize with the rich not (just) because we hope to become rich ourselves, but because we hear so damned much from them.

There���s a nasty flipside to this. If we don���t hear from people, we tend not to sympathize with them. Separate experiments by Agne Kajackaite has shown this. She got people to work where the rewards went not just to them but to a bad cause (the NRA). She found that when people chose not to know whether the money was donated to that cause, they behaved more selfishly; they worked harder to make money for themselves. ���Ignorant agents behave in a more selfish way��� she concludes.

Thigh might well have political effects. Because the worst-off have less voice, we are relatively ignorant of their suffering and so less sympathetic to them. Support for benefit cuts isn���t based solely upon outright untruths, but upon a lack of sympathy for them caused by their relative lack of voice.

Most of us, I guess, can name far more people who are in the top 5% of the income distribution than in the bottom 5%. This introduces a bias towards the rich.

My point here is that the media���s bias isn���t merely conscious and deliberate. There are more subtle ways in which it serves the interests of the well-off.

May 16, 2017

Top taxes & growth

Rich people don���t like paying taxes. This is pretty much the only thing we���ve learned from some of the hysterical reaction in the papers to Labour���s plan to raise taxes on the rich.

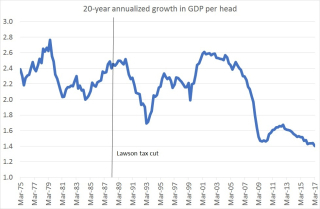

Let���s remember the historical facts here. Low tax rates aren���t associated with faster growth ��� if anything the opposite. For example, in 1988 Nigella���s dad cut the top income tax rate from 60% to 40%. Since then, GDP per head has grown by an average of 1.4 per cent per year. That compares to growth in the 29 years before the cut of 2.6% - and that was a time which included top tax rates on earned income of over 70%. Much the same is true in the US; the economy there was stronger in the 50s and 60s when the top tax rate was 91% than it has been recently with lower taxes.

You can read this fact in three ways.

One possibility is that growth has slowed in the 00s for other reasons, and the slowdown would have been even worse, had taxes not been cut. For me, this runs into two problems: one is that some of the likely causes of slow growth, such as the banking crisis, might not be independent of top tax rates. Another is that supporters of lower taxes believe that other reforms in the 80s should have raised trend growth too ��� such as privatization, deregulation and the weakening of trades unions. If they did so, their effect was swamped by other things.

A second possibility is that lower top taxes actually cause lower growth. For example, they might incentivize financialization and hence greater financial fragility, or encourage rent-seeking such as jockeying for top jobs or CEOs extracting higher pay for themselves. Of course, higher taxes might cause some top-earners to retire or emigrate. But this doesn���t necessarily cause a big loss of output. If, say, Eden Hazard were to move to Spain in response to higher taxes here, Chelsea won���t field only ten players.

A third possibility is simply that ��� within reason - trend growth isn���t much affected one way of the other by changes in national economic policies.

To argue that higher top taxes are the ���economics of the madhouse��� requires a strong case for my third possibility and good arguments against the second and third. This, I think, would be very difficult.

All this is a story about economic growth. You could argue, however, that higher top taxes would reduce tax revenues even if they don't much affect GDP: as Alan Manning has said, tax-dodging is more sensitive to tax rates than labour supply.

Even here, though, the argument is moot. For one thing, as the IFS has pointed out, these are subject to huge uncertainty. And for another, in this context the fact that Labour���s so-called ���tax grab��� would impinge upon the ���middle classes��� such as doctors and headteachers isn���t a bug but a feature. Insofar as it does so, it���s a revenue raiser. Teachers and doctors are probably less internationally mobile than the mega-rich, and less able to use tax-dodging ruses. For the purposes of raising revenue, they are a large slow-moving target.

For me, the non-hysterical arguments against Labour���s tax plans lie elsewhere. You could argue that ��� with tax morale low partly as a result of the rise of individualism ��� they���ll decrease social solidarity. People will regard them not as the price for living in a civilized society but as a burden which subsidizes ���scroungers���. Or you could argue that the revenue raised by taxes will fuel wasteful public spending. Or you might argue that redistributive taxation isn���t enough: we need to reduce inequalities of power as well as income. Or you might argue that the tax base should be shifted from incomes to land and inheritances*. And personally, I���m not wholly unsympathetic to the view that very high taxes diminish freedom ��� though few people can consistently argue for this, given the general lack of support for liberty.

What you shouldn���t do, though, is argue that higher top taxes will wreck the economy. Other things might do that, but it���s unlikely that top taxes will.

May 13, 2017

Counterproductive austerity

Is austerity counter-productive even in microeconomic terms? I ask because the ransomware attack on the NHS seems to have been dues at least in part to a lack of spending on IT. The Register says:

The NHS is thought to have been particularly hard hit because of the antiquated nature of its IT infrastructure. A large part of the organization's systems are still using Windows XP, which is no longer supported by Microsoft, and Health Secretary Jeremy Hunt cancelled a pricey support package in 2015 as a cost-saving measure.

That ���cost saving��� might well turn out to have been no such thing. It���s possible that the cost of repairing the attack, cancelled operations and updating IT systems will offset the initial saving.

This is by no means an isolated example. Cutting prison staff looks like a ���saving���, until prisoners either riot or re-offend upon release because of a lack of rehabilitation. ���Savings��� on flood defences become no such thing when we need to repair the damage done by flooding. Low spending on social care adds to NHS costs by keeping people in hospital. Cuts in psychiatric care add to police spending. A lack of spending on schools isn���t a saving if parents pay a hidden tax by donating money to schools. And so on.

In ways like these, austerity is counter-productive. It either means shifting the burden onto other public services, or increased spending later to pay for the damage done by cuts.

This is an entirely separate point from the Keynesian one, that austerity means weaker economic activity and hence lower tax revenues. Putting the two together, though, merely reinforces the point ��� that austerity fails, in the long-term, even in its own terms.

Now, I���m not complaining here only of Tory stupidity. A similar thing happens in the private sector. In the early 00s BP���s CEO John Browne cut maintenance spending. That raised profits. But only temporarily. The savings he made were swamped by the costs incurred when the Texas City oil refinery blew up.

Browne had an excuse. He was trying to impress shareholders who were daft enough to pay more attention to quarterly earnings reports than to the ground truth of dangerous refineries.

But who is the government trying to impress? It���s certainly not bond markets, who are happy to finance government borrowing at negative real interest rates. Instead, it���s political journalists with their silly mediamacro obsession with the ���nation���s finances��� and ignorance of the ground truth of whether austerity is in fact feasible in the long run.

In saying all this, I���m not arguing against restraining government spending. There is of course a case for rooting out waste and making sustainable efficiency gains. Identifying such gains, however, can���t be done by here-today, gone-tomorrow politicians and managers who care only about tough talk and impressing journalists or hitting short-term targets. Genuine, lasting restraint requires empowering public sector workers (who have both knowledge of ground truth and skin in the game to ensure efficient services in the future) to identify genuine waste. Austerity, when combined with managerialism, is just daft.

May 12, 2017

The bias against emergence

John Humphrys gave us a good example of the BBC���s bias this morning ��� and it���s not the sort you might think.

In discussing the Bank of England���s forecast that real wages will continue to fall this year, he asked (2���10��� in): ���are we going to keep getting poorer because of Brexit?���

Now, I think Brexit is one the stupidest things this country has done for years. But it alone is only a minor cause of falling real wages (at least for now!). Three facts tell us so.

First, real wages have stagnated ever since 2007 ��� long before Brexit was heard of.

Secondly, we haven���t suffered a deterioration in the terms of trade. These have actually risen since May. Yes, import prices have risen. But so have export prices. Exporters are seeing fatter profit margins. Insofar as they share these with workers, real wages should rise for at least some workers.

Higher inflation alone cannot explain falling real wages. They merely pose the question: why aren���t workers getting protection from inflation in the form of nominal wage rises?

The answer, as Mark Carney said (pdf) yesterday, is that productivity is falling ��� which means a smaller pie for everyone ��� and that labour market slack gives employers��� the power to hold down wages.

Granted, these aren���t the whole story, and Brexit might be holding down wages by increasing firms��� uncertainty. But they are a big part of the story. Why, then, did Humphrys ignore them and focus on Brexit?

I fear that we have here is another example of a bias against emergence. Political journalists especially focus upon conscious political actions to the neglect of emergent processes. Brexit is a political choice whereas other, perhaps bigger, influences on real wages are the complex unintended products of millions of dispersed decisions. So Humphrys pays the former more attention.

This is not an isolated example. Political journalists discuss fiscal policy as if government borrowing were set by Chancellors and overlook the (large) extent to which it is the counterpart of global emergent processes such as the savings glut and corporate cash-hoarding.

Nor is it confined to journos. Leftists sometimes blame rising CEO pay on bosses��� greed, as if the rest of us would turn down pay rises, and under-estimate the extent to which it is the result of partly-emergent processes such as globalization (pdf), deunionization, agency failure or managerialist ideology.

In this respect, the BBC has what John Birt and Steve Richards called a ���bias against understanding.��� In downgrading the importance of emergence, it stops viewers and listeners from understanding social phenomena.

If this bias merely led to ignorance, it wouldn���t be so bad. But it might have a more systematic effect. If we underweight emergence, we overweight the role of conscious individual agency. This causes us to exaggerate what politicians and business leaders can achieve if only they display strong leadership. And that, in turn, helps to sustain inequalities of income and power.

May 11, 2017

The problem of ignorant voters

The Times recently reported on a discussion with a voter in Hull:

���I���m not really into any of that stuff��� said Cody, 22, our waitress at the Goldenfry chip shop. ���I think I voted Labour at the referendum thing but I���m not sure.���

This highlights an important fact about politics ��� that millions of people aren���t interested in it. They are what Jason Brennan calls hobbits. Sean Kemp says: ���The vast majority of people don���t pay any attention to the general election whatsoever��� (2���30��� in). Yougov, for example, have found that only 15% of voters have heard the Tory slogan ���strong and stable��� even though its endless repetition has driven many of us potty.

Not unrelatedly, other polls show that voters are systematically and woefully mistaken about basic social facts.

The left likes to blame the media for its unpopularity. But very many voters avoid newspapers and TV news. This doesn���t mean they don���t have distorted views: as I���ve said, people are prone to countless cognitive biases without the influence of the media.

Now, in one sense, this isn���t a bad thing. It might be rational to avoid politics, as you can���t, individually, do much about it and it���ll only make you angry. And all of us are ill-informed about countless matters.

Most of the time, however, those of us who are ignorant and irrational shut up and mind our own business: exceptions to this include newspaper columnists and callers to 6-0-6.

The problem is, though, that voting is another of these exceptions. Millions of ignorant people will cast a vote next month.

This would not be so bad if their ignorance and irrationality were random and so merely introduced white noise into the election. But it���s not. It���s systematic. For example, people over-estimate the number of immigrants in the country and their adverse effect upon jobs and public services; over-estimate the level of welfare benefits and fraud; and mistakenly think the public finances are analogous to household finances. And this is not to mention the many ways in which ideology sustains inequality ��� what John Jost calls system justification (pdf).

Systematically biased beliefs result in systematically biased politics, in two ways.

One is style. Mass inattention causes politicians to focus upon what ���cuts through��� rather than what is right. A lot of confusion between pundits and journalists on the one hand and intellectuals on the other arises because the former ask ���what sells?��� whilst the latter ask ���what���s true?��� This was summed up by an exchange between Nick Robinson and Jonathan Portes when the latter tried to tell the truth about immigration. Robison replied:

A fine economist he might be, but I suggest he would not have a chance of getting elected in a single constituency in the country. It is a widespread view that there is exploitation of the benefits system by migrants.

In the same way, vague images matter more than empirical evidence. So Theresa May can peddle a picture of stability and competence without over-much inspection of whether this has any factual basis.

There���s also a substantive distortion. Non-issues such as immigration become too important, whilst things that really matter, such as how (if at all) it���s possible to raise productivity are under-emphasized. And fiscal policy becomes an idiotic demand that spending plans be ���fully costed��� rather than a matter of what the fiscal stance should be.

In complaining of all this, I���m not making an especially partisan point. Yes, it���s consistent with Marxian ideas about ideology. But I���m also agreeing with Janan Ganesh that ���the dysfunction in politics stems from public indifference to politics���. And I���m echoing Jason Brennan���s arguments against democracy and Edmund Burke���s view that the judgment of MPs should sometimes over-ride the ���hasty opinion��� of the mob.

Instead, I���m asking: how can we achieve a better polity ��� one that respects people���s interests and maintains respect for facts and rationality in political debate ��� in the face of mass inattention to politics? With politics dominated by the ignorant at one end and by partisan obsessives at the other, this important question goes unasked.

May 10, 2017

The "fully costed" fallacy

One of the many irritants of this election campaign is the demand by the media that the parties��� spending plans be ���fully costed���, and the parties��� kow-towing to this demand: listen, for example, to this exchange between Sara Montague and Tim Farron (2���23��� in).

What���s irritating about this is that rests upon an elementary fallacy ��� that governments must act like prudent housekeepers, accounting for every penny.

This ignores the fact that the public finances are not under the government���s control. Government borrowing is the counterpart of private sector saving (both here and overseas). If the private sector wants to save more, then government must borrow more; the alternative is for it to depress the economy by cutting spending or raising taxes.

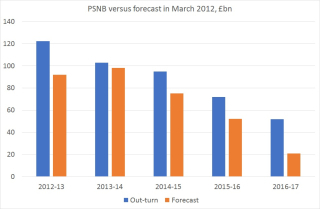

My chart shows the point. It compares actual government borrowing against forecasts made in March 2012. It���s clear that borrowing has overshot ��� by a cumulative ��107bn. That means the Tories have, in effect, made ��107bn of ���uncosted��� spending over the last five years. Meanwhile, journalists whine about a few hundred millions of "uncosted" Labour spending.

In truth, though, nobody much cares about that ��107bn of uncosted spending. Whilst the Tories have "overspent", bond yields ��� the cost of government borrowing ��� have consistently fallen. The two are related. The same global savings glut and demand for safe assets that have driven down bond yields have also caused higher than expected private savings and hence higher than expected government borrowing.

The main task of government is not to fully cost its spending. It is instead to ensure a healthy economy. And for now at least this requires higher borrowing - or uncosted spending. Negative real gilt yields mean that financial markets are paying the government to borrow: why not take up the offer?

"Expenditure creates its own income��� said Keynes:

The only chance of balancing the Budget in the long run is to bring things back to normal, and so avoid the enormous Budget charges arising out of unemployment���Look after the unemployment, and the Budget will look after itself.

Strictly speaking, this isn���t wholly true: low wages and a lack of capital spending are damaging the budget as much as unemployment, and it���s worldwide stagnation that���s the problem rather than just UK weakness. But the wider point holds ��� that the government budget will balance if and only if the economy is healthy. Demands for prudence and full costings won���t help and will in fact be counter-productive.

Now, you might think I���m just making elementary economic points here. I am. But there���s something else. It���s that the demand by political journalists for full costings isn���t just lousy economics. It���s also deeply biased. It���s based on the assumption that political ���competence��� consists of mindless penny-pinching rather than a grasp of economic reality. This generates a bias against economic understanding amongst the electorate, and against those politicians who do understand economics. You didn���t think the BBC was impartial, did you?

This doesn���t just coarsen political debate. It ruins lives. Why should children suffer the lifetime burden of being badly educated because of the economic illiteracy of imbecile journalists?

May 9, 2017

The need for an immigration target

Good judges are sceptical of Theresa May���s repetition of her failed promise to reduce migration. The Migration Observatory says the target is ���not feasible in the short term and difficult to achieve in the long-term.��� And Stephen Bush says that even if it could be achieved, the effects would be ���pretty terrible���.

This is true. And it���s irrelevant. It misses the point that the Tories need an immigration target, and they need it to fail. This is because it���s a deflection strategy.

The Tories want to blame immigration for poor public services and low wages. For the most part, however, this is just plain false. Immigration is only a minor contributor to low wages and to pressure on the NHS. What���s far more important for the latter is austerity. And wages have been depressed by many things other than immigration, such as declining trades unions, austerity, financialization (pdf), power-biased technical change and the countless factors (among them bad management, the effects of the financial crisis and low investment) that have caused productivity to stagnate.

The Tories, however, cannot say this. They can���t blame their own policies, and nor can they comfortably point out that capitalism is failing. They need a scapegoat. Immigration is it. Hence the need to talk up the need to reduce migration.

By the same token, though, they need to fail to do so. What if migration were to fall whilst public services remain stretched and real wages continue to stagnate? It would then be clear that immigration was indeed a red herring and that our problems owed more to Tory policy and capitalist failure. In failing to meet the target, however, the Tories can maintain the pretence that, if only they could reduce migration, then pressure on public services and wages would be relieved.

From this perspective, failure works better than success.

Now, you might object here that this looks like a conspiracy theory, or at least like the sort of functional explanation of which Jon Elster, one of my great intellectual heroes, was sceptical.

I think I can escape this charge. I���m not arguing that the Tories originally adopted the target because of this motive. They���re not that clever. Cameron chose it simply because he was pandering to the right. By sheer luck, however, the target serves a useful function ��� all the more so because it won���t be hit.

Chris Dillow's Blog

- Chris Dillow's profile

- 2 followers