Chris Dillow's Blog, page 64

March 13, 2017

Capitalism & creativity

It���s increasingly difficult to distinguish between serious journalism and the Daily Mash. So it is with this piece from the excellent Andrew Hill, who describes how:

executives and entrepreneurs are ���microdosing��� on illicit substances and submitting to transcranial magnetic stimulation ��� normally used to treat depression ��� in search of creative highs.

Such activities seem to me to completely mischaracterise the creative process, especially under capitalism.

For one thing, most new ideas are bad ones: the replication crisis in academia reminds us of this. Creativity doesn���t arise from a high or spark of genius, but from the dedication to keep going through the failures until you find the success. Thomas Edison, one of the most creative capitalists of all, said: ���I have gotten a lot of results! I know several thousand things that won���t work.��� That was why he claimed that ���genius is 1% inspiration and 99% perspiration.��� In the same spirit James Buchanan used to advise graduate researchers: ���keep the ass in the chair.���

In this context, it���s apt that Andrew should mention Richard Branson ������birthing��� Virgin Galactic in a Necker Island hot-tub under the stars.��� The important fact about Virgin Galactic is that it has so far failed to achieve what the USSR managed in 1961: putting a man in space. Grunt work matters at least as much as ���birthing.���

Secondly, creativity is not the road to riches. As William Nordhaus famously pointed out, innovation isn���t often very profitable. And where it is, it is thanks to intellectual property laws and to monopoly power rather than to innovation itself. As Warren Buffett said, profits require economic moats ��� barriers to entry. The digital age has much in common with the feudal age: in both, wealth comes from the power to exclude others. Where this power is lacking, even the greatest creative talents find life ���monetarily impossible.���

Thirdly, the binding constraint upon creativity is not so much our minds as our institutions. One of these is the intellectual property system. Another is access to finance. Danny Blanchflower and Andrew Oswald have shown that it is this (pdf), rather than character traits, that makes an entrepreneur ��� thus vindicating Kalecki���s claim that ���the most important prerequisite for becoming an entrepreneur is the ownership of capital.���

And of course yet other constraints come from managerialist capitalism. One of these is that, having learned that innovation doesn���t pay, firms have learned to do less of it. Another is that the pursuit of efficiency means people have less downtime to innovate. Yet another is that creativity comes from making connections but the silo mentality fostered by hierarchical management prevents these being made. Yet another is that some innovations such as new financial assets require that a collective action problem be overcome, which individual capitalists cannot do.

In my tiny trivial way, I exemplify these points. The best financial advice is well-established, and embellishments to it might well be worse than useless. And even if I were to have the most brilliant idea for a book, I���d not be able to find the time to write it or a publisher. So there���s not much point my being creative.

What���s true of me is even more true for most people. Andrew discusses ���flow��� ��� complete absorption in an activity. Most of us, though, find this outside work: in sport, music, gardening or crafts (I���m amazed how many of my friends here in Rutland have craft rooms). Perhaps the principal way in which capitalism fosters well-being is by permitting a shortening of the working week. As for how far such shortenings are due to geniuses having creative highs, I leave that verdict to Clay Davis.

March 9, 2017

How capitalist power works

The two main news stories this morning both gave us an insight into how capitalist power works.

The first item is the increase in NICs despite repeated Tory promises not to do so. It would be nice to think this will lead to a backlash against the Tories. But it might not. People don���t like to admit even to themselves that they were stupid enough to let themselves be conned. One trick to protect their egos is to adopt na��ve cynicism towards politicians in general: ���they���re all the same, aren���t they?���. As the Economist put it:

It is tempting to think that, when policies sold on dodgy prospectuses start to fail, lied-to supporters might see the error of their ways. The worst part of post-truth politics, though, is that this self-correction cannot be relied on. When lies make the political system dysfunctional, its poor results can feed the alienation and lack of trust in institutions that make the post-truth play possible in the first place.

But who benefits from this lack of trust?

Capitalists, that���s who. Collective action, exercised in part through state politics, is a potential constraint upon capitalist power. The less trust people have in politicians, the less this constraint will be used. Colin Crouch has said:

An atmosphere of cynicism about politics and politicians���suits the agenda of those wishing to rein back the active state, as in the form of the welfare state and Keynesian state, precisely in order to liberate and deregulate���private power (Post-Democracy, p23)

Our second item is the news that BlackRock is paying George Osborne ��650,000 a year. What are they buying? It���s not his economic expertise ��� he���d struggle to get a minimum wage job on that account ��� nor even his contacts. Instead, BlackRock is offering an incentive to the world���s finance ministers. It���s telling them that they too can get big money if they behave themselves in office*.

Such behaviour consists of giving the industry a favourable tax regime, lightish regulation, and ensuring a good flow of easy money. Osborne���s policy of fiscal conservatism and monetary activism had the effect of boosting asset prices (pdf), to the benefit of firms like BlackRock**.

It���s through mechanisms like this that capitalists gain undue influence over the state: there of course several other mechanisms, not all of which are exercised consciously or deliberately.

This influence isn���t perfect ��� we���d probably not have had Brexit if it were ��� but it exists. The idea that democracy means equality of political power is a fiction in capitalism.

You might think this is a Marxist point. I prefer, however, to think of it as a Cohenist one:

Everybody knows the fight was fixed

The poor stay poor, the rich get rich

Except that not everybody does know the fight is fixed, because the question of how capitalist power is exercised ��� like other questions such as whether capitalism impedes productivity or whether hierarchy is justifiable ��� is not on the agenda. But then, the issue of what gets to be a prominent political question and what doesn���t is another way in which power operates to favour capitalists.

* I���m not saying this is BlackRock���s motive ��� but it certainly looks like the effect of its decision.

** You might think the revolving door between banks and regulators serves a similar function. This, though, is less clear.

March 7, 2017

On salient identities

I have size ten feet. This is a biological fact which I cannot change. In some contexts, it���s of utmost importance, such as in a shoe shop. In other contexts, though, it���s irrelevant.

This might sound utterly trivial. But it���s why I agree with Phil that David Goodhart���s talk of ���legitimate ethnic interest��� exudes ���moral foulness.���

The thing is, we all have multiple identities: I���m tall, white, Oxford-educated, bald, heterosexual, male, bourgeois with a working class background, an economist, an atheist with a Methodist upbringing. And so on and on. The question is not: what are my identities? But rather: which of these identities matter? Amartya Sen has written:

A Hutu labourer from Kigali may be pressured to see himself only as a Hutu and incited to kill Tutsis, and yet he is not only a Hutu, but also a Kigalian, a Rwandan, an African, a labourer and a human being. Along with the recognition of the plurality of our identities and their diverse implications, there is a critically important need to see the role of choice in determining the cogency and relevance of particular identities which are inescapably diverse. (Identity and Violence, p4)

Even if you accept biological essentialism, the question of which of our multiple identities becomes salient is surely in large part a social construct. In Sen���s example, it took propaganda and pressure to raise the prominence of Hutu identity to genocidal importance. In the UK today, there���s a prominent identity divide between Leavers and Remainers, but this was much less significant a few years ago.

Not only does biology not suffice to determine the salience of identities, nor even does economics. For example, tall people earn more than short ones and good-looking people more than ugly ones, but politics isn���t divided along these lines. The converse is also the case; the isn���t much economic difference between the English and Scots, but there is a political difference.

Marxists have long been aware of this. We believe the working class has distinct economic interests. But the job of getting them to see this - of building class consciousness - is a tough one. Such awareness requires industrial and political action.

Which brings me to my beef with Goodhart���s piece. No good can come from raising the salience of racial or ethnic identities. I say so for four reasons:

- It���s not obvious that I have much common interest with (say) an unskilled 20-year-old ��� which of course is not to say our interests necessarily conflict. Attempts to identify us as a common group will generally involve distinguishing us from other ethnic groups. I see no upside in this, and plenty of downside.

- If we must think in racial terms, whites are the predominant group in the UK: yes, we should ignore the bleating of some imbecile rightists. Asking a dominant group to assert its self-interest will increase inequality and domination.

- One of the easiest ways people have of conning themselves is to come to think that their interests are morally legitimate. Slaver-owners, for example, found it very easy to persuade themselves that slavery was justified by blacks��� supposed inferiority. Inviting white people to pursue their interests almost inevitably means inviting them to believe in their moral superiority. This must of course be rejected.

- Salience is a zero-sum game. If ethnic divisions become more salient, others thus become less so. Not least of these divisions is that between rich and poor. The politics of ethnicity thus serves, in practice, to defend and widen class inequalities. As LBJ said: ���if you can convince the lowest white man he���s better than the best colored man, he won���t notice you���re picking his pocket.���

My point here is so simple and obvious that I���m embarrassed to say it. We���re all different in all kinds of ways. Which of these differences matter, and by how much, is a social construct. Ideally, ethnic differences would matter no more than differences in shoe size. Any attempt to raise their significance moves us away from this ideal and is thus regressive.

March 6, 2017

Limits of supply-side reform

Philip Hammond says he plans to use Wednesday���s Budget to get us ���match fit��� for Brexit. This reminds me of an old error of Chancellors and political commentators ��� their habit of under-estimating just how damned difficult it is to increase long-run growth.

In fact, John Landon-Lane and Peter Robertson have shown (pdf) that the data are consistent with the possibility that national government policies have no discernible impact upon long-run growth at all. This is because most developed economies grow at much the same rate as each other, give or take a standard error and pathological exceptions such as perhaps Italy or Japan.

Dietz Vollrath has shown why this is. It���s because economies are very slow to converge to higher levels of potential output, even if such levels can be achieved.

To see why, imagine something happens to raise the level of potential GDP growth ��� say, some technical innovation or your pet policy gets implemented. For this to affect actual growth, companies must first see new profit opportunities, then persuade financiers to back them, and then retrain workers, install new equipment, hire more staff and so on. But there���s mountains of things that can go wrong here: new technology might not work well; it takes time for workers to learn new jobs; managers can lose control of costs as they focus on expansion; and so on. All these problems throw sand into the wheels and stop the economy adjusting swiftly to its higher potential level.

Resources ��� capital and labour ��� are not very fungible. One of the consistent errors of free market economists has been their unwillingness to see this.

But it���s not just them who make this mistake. In a new paper Charlie Cai and colleagues show that equity investors tend to pay too much for growth stocks because they under-estimate the difficulties firms have in expanding: expansion usually entails falls in asset turnover and in margins, facts which themselves limit that expansion.

This micro evidence fits the macro evidence that convergence towards higher potential output is slow. It also tells us that the inability to appreciate this doesn���t arise merely from motivated reasoning and political ideology, but rather from a widespread cognitive bias ��� a tendency to over-rate the importance of salient things such as policy announcements or current corporate growth and so under-rate the importance of the countless low-level barriers to growth.

For me, this has two policy implications.

One is that Chancellors should worry less about raising long-run growth and more about getting macroeconomic policy right. Failings in the latter can easily more than offset good supply-side policies: for example, Nicholas Oulton���s assessment of the Thatcher reforms was that ���microeconomic success has been masked by macroeconomic failure.��� As James Tobin rightly (pdf) said, ���it takes a heap of Harberger triangles to fill an Okun gap.���

Secondly, although the adjustment to higher potential output is slow, that to lower output might not be: companies can quickly close factories and shed workers. Economic policy should therefore obey a form of the Hippocratic oath: first, do no harm.

With this government committed to both fiscal austerity and a hard Brexit, it is disregarding both these principles. As our media is more likely to focus upon Hammond���s cheap talk than upon hard economic realities, it will probably not sufficiently be blamed for this.

March 4, 2017

Yes, slavery matters

David Olusoga says we British should be more aware of our role in the slave trade. I agree.

For one thing, slavery is not just (just!) a crime against humanity that many would like to forget. Its effects are still with us. Avidit Acharya, Matthew Blackwell and Maya Sen show (pdf) that:

Whites who currently live in Southern counties that had high shares of slaves in 1860 are more likely to identify as a Republican, oppose affirmative action, and express racial resentment and colder feelings toward blacks.

Glenn Loury has written:

The communal experience of the slaves and their descendants [was] shaped by political, social, and economic institutions that, by any measure, must be seen as oppressive. When we look at ���underclass culture��� in the American cities of today we are seeing a product of that oppressive history.

Graziella Bertocchi shows that states with lots of slaves (pdf) in 1860 have high racial inequality of education today, and because of this have lower incomes. And Robin Einhorn traces Americans��� hatred of taxes back to slaveholders.

The impact of slavery, though, isn���t confined to the US. Nathan Nunn shows that the slave trade has impoverished Africa today, by reducing trust and political development.

Culture matters for the economy and society. Culture is transmitted from generation to generation. And the culture that sustained slavery, and was produced by it, lingers today. We are creations of our history.

Of course, this is more true of the US and Africa than the UK. But can we really rule out the possibility of a zero impact here?

There���s a second reason to be aware of slavery. It teaches us that inequality did not arise from a process of free exchange but rather from the most barbaric practices. Although there���s debate about exactly how much the fortunes created by slavery were parlayed into industrial capital and transmitted down the generations to today, it���s unlikely that today���s inequalities are wholly untainted by that primitive accumulation. As Marx said, capital comes into the world ���dripping from head to foot, from every pore, with blood and dirt.���

There���s something else. The brutality of slavery teaches us that men do not voluntarily exercise self-restraint when pursuing their self-interest. Adam Smith famously wrote that men have a ���propensity to truck, barter and exchange.��� But unlike some of his epigones, he was not so stupid or na��ve as to believe that ���doux commerce��� was our only impulse. He also wrote:

The pride of man makes him love to domineer, and nothing mortifies him so much as to be obliged to condescend to persuade his inferiors*. Wherever the law allows it, and the nature of the work can afford it, therefore, he will generally prefer the service of slaves to that of freemen.

And he���ll exploit them to the maximum. In The Great Leveler, Walter Scheidel shows that ���early societies tended to be about as unequal as they could possibly be.���

This tells us that the obstacles to inequality lie not in the morality of the dominating class but in constraints upon their power. At a time when a serious newspaper can carry a piece applauding the pursuit of ���legitimate ethnic interest���, this is a lesson that needs repeating.

* I don���t know whether we should give Smith the benefit of the doubt and read ���inferiors��� ironically.

March 2, 2017

In defence of PPE

In The Econocracy, Joe Earle, Cahal Moran and Zach Ward-Perkins accuse economics degrees of imparting into their victims narrow technical skills and rote-learning whilst discouraging critical thinking. One solution to this would be for economics to be part of a multi-disciplinary degree, so that students gain a wider skill set.

And yet the most prominent of these degrees ��� Oxford���s PPE ��� is also under attack, as Andy Beckett describes.

There���s nothing new about such attacks: they are as old as the degree itself. But they are, nevertheless, wrong.

For one thing, there���s much to be said for broader degrees. As journalists so often demonstrate, there is a shortage of people who can both write and add up: Oxford���s economics has, for good and ill, become more mathematical since my day.

Of course, breadth comes at the expense of depth ��� though as The Econocracy reminds us, depth has its drawbacks too. But a first degree should be the start of one���s education, not the end*. I followed my PPE with a masters in economics and then on-the-job training. I learnt the detail of economic statistics in my first job: back in the 80s and 90s there was money to be made from knowing when seasonal adjustments weren���t reliable. Many PPEists take a similar route. PPE, which demands the ability to absorb a lot of ideas very quickly, is good preparation for this later learning.

And I don���t get the allegation that PPE produces a particular mindset. I know I might be guilty of ingroup bias here, but I don���t see that people like Seamus Milne, David Cameron, John Gray, Paul Johnson, Mark Reckless and Tim Harford (to name a few) have much of a common ideology.

Andy Beckett says that PPEists are ���confident, internationalist [and] intellectually flexible���. But any decent education should produce such people. It should also produce people who are out-of-touch with bigots, fanatics and philistines. The fact that Farage talks of ���PPE bollocks��� should be worn as a badge of honour.

Here, though, we must distinguish between what PPE produces and what it reveals. There���s a certain type of person who does PPE: clever, hard-working and ambitious (entry onto the course is very competitive ��� more so than for, say, geography). And guess what: clever, hard-working and ambitious people who are interested in politics will disproportionately become prominent politicians.

What look like the faults of PPE might therefore instead be the faults of the sort of people who choose to do PPE at Oxford.

In this context, critics of PPE are missing a big thing: class. The vices they rightly identify have less to do with PPE and are more the product of our class system.

It is the case that some PPEists are and have been overconfident about their abilities. But is this really due to PPE? I suspect instead that it���s because many PPEists ��� though no more than other Oxford students ��� come from posh backgrounds. And it���s poshness that produces overconfidence. David Cameron and Toby Young are arrogant arseholes, but it probably wasn���t PPE that made them so.

Equally, the claim that the ruling class have lost touch with ���ordinary voters��� has less to do with PPE and more to do with the fact that that class has been drawn from a narrow social circle. And increasing class divisions - such as the decline of unions and rise of managerialism ��� have widened the gap between rulers and ruled.

Even more importantly, the backlash against ���elites��� isn���t motivated by popular discontent with the PPE syllabus. Its rooted in the stagnation of real incomes caused by secular stagnation and the financial crisis.

It is capitalism that has failed, not PPE. In distracting us from this fact, critics of PPE are not just wrong but reactionary.

* Education is what happens after you leave school; what happens before is indoctrination and aversion therapy.

February 28, 2017

Labour's crisis: Cameron's fault

It���s widely agreed, and also true, that the Labour party is in crisis in part because of bad leadership. What���s not sufficiently appreciated, however, is that the bad leadership is not just Corbyn���s. It���s also Cameron���s. Labour is paying the price of his failed policies.

I mean this in two related ways. One is that fiscal austerity contributed to stagnant living standards. And stagnation, as Ben Freidman has shown, breeds intolerance. This has contributed not only to harsher anti-immigration sentiment, but also to immigration becoming a more salient issue. And Labour is regarded as weak on this.

Secondly, it was Cameron who gave us Brexit, not least because his austerity policies increased support for the Leave cause. This has hurt Labour in three ways:

- It has created a perceived division within the party between its young, metropolitan outward-looking supporters on the one hand and more socially conservative working class Leavers on the other. Granted, this division is exaggerated: as John Curtice points out, most Labour supporters even in the party���s ���heartland��� voted Remain. But the sense of a divide is real.

- It has allowed May and the Tory right to claim to embody the ���will of the people���. This has left Labour looking out of touch. And it���s created a dilemma of how the party can claim to be on the side of the people when it opposed a policy they favour.

- Brexit has diverted attention from policy areas where Labour might be stronger. Imagine it hadn���t happened. What would today���s big issues be? Chances are, they���d be the NHS and social care ��� issues on which voters better trust Labour.

Now, I don���t say all this to complain about an injustice. Westminster politics has little to do with fairness or meritocracy.

Nor do I say so to exculpate Corbyn: the fact that he's been dealt a bad hand doesn't justify him playing it badly.

Instead, I do so to point out that social affairs are complex and unpredictable. Even those of us who have long opposed austerity did not foresee that it would be Labour, more than the Tories, are paying the price of its ill-effects.

We tend to think that bad government policies will boost support for the opposition. It ain���t necessarily so.

Which brings me to my worry. Nick Cohen says that when voters realize that Brexit is a ���godawful mess��� they���ll turn against the ���superliars��� who are imposing it upon us. This might be too optimistic. Instead, I fear there���s a danger of a backfire effect which will see even greater hostility to immigrants and experts.

It���s not just truth that does not prevail in politics. Nor, often, does justice.

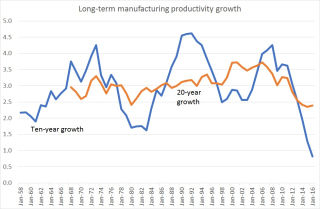

On manufacturing productivity

Some people criticized my last post on the grounds that we���d expect productivity growth to have slowed down in recent years because the economy has shifted from manufacturing ��� where productivity gains are easier to achieve or measure ��� to services, where they are less easy to achieve or measure.

My chart helps to speak to this objection. It shows productivity growth for manufacturing only. I���m taking Bank of England data since 1948, updated for last year from the ONS.

This shows that productivity growth did accelerate in the 80s: ten-year growth peaked in 1981-91. You might read that as evidence that the Thatcher reforms did raise productivity. However, in recent years productivity has slowed. In the last 20 years, it���s grown by 2.4% per year, which is almost a percentage point less than it grew in the 1953-73 peak.

If neoliberalism did raise productivity growth, it did so only briefly.

I���ll not accept the objection that productivity growth slowed recently because of the financial crisis. True, it did, through several channels. But the crisis was not an accident. Crises are an inherent feature of capitalism. Claiming that productivity would have done well but for the crisis is like a football manager claiming that his side played well except for the six goals they conceded.

What���s more, the productivity slowdown recently is surprising because two things should have raised it.

One is offshoring ��� both outsourcing and the displacement of low-wage manufacturing in the UK by cheaper imports. This should have raised productivity in the same way that dropping a team���s worst batsmen would raise the side���s batting average. You might detect this effect in the 00s, but not more recently.

The other is robots. There���s not much evidence in these data that robots and digitization are raising productivity.

These data, I think, leave the debate open. They are consistent with my claim that neoliberalism is now depressing productivity. But they���re also consistent with the notion that perhaps neoliberal reforms did temporarily raise productivity, but that effect has now been outweighed by secular stagnation effects: less innovation, diminishing returns and suchlike.

I���m surprised and disappointed that we don���t hear more free market pessimism ��� the idea that free markets are a good thing but their effect on growth is offset by the dead hand of diminishing returns. This was David Ricardo���s view, and it seems to me a reasonable one now.

February 26, 2017

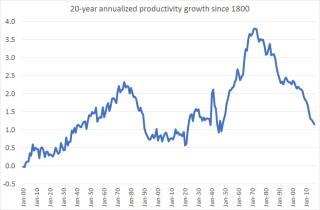

Neoliberalism & productivity

Chris Edwards says the privatizations started by Thatcher ���transformed the British economy��� and boosted productivity. This raises an under-appreciated paradox.

The thing is that privatization isn���t the only thing to have happened since the 1980s which should have raised productivity, according to (what I���ll loosely call) neoliberal ideology. Trades unions have weakened, which should have reduced ���restrictive practices���. Managers have become better paid, which should have attracted more skilful ones, and better incentivized them to increase productivity. And the workforce has more human capital: since the mid-80s, the proportion of workers with a degree has quadrupled from 8% to one-third.

Neoliberal ideology, then, predicts that productivity growth should have accelerated. But it hasn���t. In fact, Bank of England data show that productivity growth, averaged over 20 years, has trended down since the 1970s.

Why?

It could be that neoliberal reforms did give a short-lived boost to productivity. I���m not sure. As Dietz Vollrath says, economies are usually slow to respond to a rise in potential output. If there had been a big rise in potential output, therefore, it should show up in the data on 20-year growth. It hasn���t.

Another possibility is that the productivity-enhancing effects of neoliberalism have been outweighed by the forces of secular stagnation ��� the dearth of innovations and profitable investment projects.

But there���s another possibility ��� that neoliberalism has in fact contributed to the productivity slowdown.

I���m thinking of three different ways in which this is possible.

One works through macroeconomic policy. In tight labour markets of the sort we had in the post-war years, employers had an incentive to raise productivity because they couldn���t so easily reply upon suppressing wages to raise profits. Also, confidence that aggregate demand would remain high encouraged firms to invest and so raise capital-labour ratios. In the post-social democracy years, these spurs to productivity have been weaker.

Another mechanism is that inequality can reduce productivity. For example, it generates (pdf) distrust which depresses growth by worsening the quality of policy; exacerbating ���markets for lemons��� problems; and by diverting resources towards low-productivity guard labour.

A third mechanism is that neoliberal management itself can reduce productivity. There are several pathways here:

- Good management can be bad for investment and innovation. William Nordhaus has shown that the profits from innovation are small. And Charles Lee and Salman Arif have shown that capital spending is often motivated by sentiment rather than by cold-minded appraisal with the result that it often leads to falling profits. We can interpret the slowdowns in innovation and investment as evidence that bosses have wised up to these facts. Also, an emphasis upon cost-effectiveness, routine and best practice can deny employees the space and time to experiment and innovate. Either way, Joseph Schumpeter���s point seems valid: capitalist growth requires a buccaneering spirit which is killed off by rational bureaucracy.

- As Jeffrey Nielsen has argued, ���rank-based��� organizations can demotivate more junior staff, who expect to be told what to do rather than use their initiative.

- The high-powered incentives offered to bosses can backfire. They can incentivize rent-seeking, office politics and jockeying for the top job rather than getting on with one���s work. They can crowd out intrinsic motivations such as professional pride. And they can divert (pdf) managers towards doing tasks that are easily monitored rather than ones which are important to an organization but harder to measure: for example, cost-cutting can be monitored and incentivized but maintaining a healthy corporate culture is less easily measured and so can be neglected by crude incentive schemes.

- Empowering management can increase opposition to change. As McAfee and Brynjolfsson have shown, reaping the benefits of technical change often requires organizational change. But well-paid bosses have little reason to want to rock the boat by undertaking such change. The upshot is that we are stuck in what van Ark calls (pdf) the ���installation phase��� of the digital economy rather than the deployment phase. As Joel Mokyr has said, the forces of conservatism eventually suppress technical creativity.

All this is consistent with the Big Fact ��� that aggregate productivity growth has been lower in the neoliberal era than it was in the 1945-73 heyday of social democracy.

I���ll concede that this is only suggestive and that there might be another possibility ��� that the strong growth in productivity in the post-war period was an aberration caused by firms catching up and taking advantage of pre-war innovations. This, though, still leaves us with the possibility that slow growth is a feature of normal capitalism.

February 23, 2017

Ignoring people

Are economists - even when they are right - guilty of ignoring people���s real experiences?

I ask because of the row over business rates. Some businesses face a big increase in these. To this, it���s tempting for economists to point out the incidence of rates. This often falls not upon businesses themselves but upon landlords: higher rates lead to lower rents, which means that rates are in effect a cack-handed form of land tax. The IFS has said (pdf):

Much of the burden of business rates is passed on from the occupiers of non-domestic properties to the properties��� owners (if different), via reductions in the properties��� market rental values.

I believe this. But I sympathize with business owners who aren���t convinced. The question is: how is the burden passed on? One way is through rents being renegotiated ��� a process which favours bigger businesses against smaller landlords. Another way is by firms moving to cheaper premises, or threatening to do so. Even the latter entails costs ��� of researching rents on plausible premises and being distracted from the tough day-to-day job of running your business.

Even in cases where the burden of rates is passed onto landlords, business owners suffer hassle. Talk about tax incidence ��� even if it is true ��� underplays this hassle. Economists��� analysis of comparative statics overlooks the human difficulties of moving from one outcome to the other. Real life is lived in time lags and in disequilibria.

Rates are not the only example of this. I suspect immigration might provide another. Here���s one study of how immigration affects natives:

Native Europeans are more likely to upgrade their occupation to one associated with higher skills and better pay, when a larger number of immigrants enter their labour market. They are also more likely to start a self-employment activity. As a consequence of this upward mobility their income increases or stays the same in response to immigration.

Again, I find this plausible. And again, it neglects the lived experience of those affected. Even those who make the upgrade well face a period of uncertainty: what job can I do? Will I get it? Will my business succeed? And so on.

Now, I stress here that I���m looking at cases where I believe economists to be more or less right. In other cases, some economists are guilty of a bigger error ��� of over-estimating the likelihood of a benign adjustment. Those who think that jobs lost because of the UK leaving the single market can be offset by ones created by more exports to Australia are making the same mistake Patrick Minford made in the 1980s when he supported pit closures on the grounds that redundant miners would find jobs as supermodels and astronauts*; they are over-stating people���s flexibility.

Instead, I���m making a point with a heavy heart ��� that even good, empirical economics can overlook real lived experience. Perhaps economists need more ethnography. This might be one reason (of several) why there is a big and regrettable chasm between economists and lay people.

* He didn���t use these examples, but he might as well have done.

Chris Dillow's Blog

- Chris Dillow's profile

- 2 followers