Chris Dillow's Blog, page 63

April 4, 2017

Wages & productivity

Would higher wages boost economic growth? They might, if the marginal propensity to spend out of wages is higher than that out of profits. However, Ben Chu suggests a different mechanism ��� that higher wages might stimulate growth via the supply-side rather than demand-side:

Perhaps wage increases will prompt higher productivity in firms that employ low-wage labour. Perhaps, in order to protect their profit margins, managements will be spurred into increasing the efficiency of their operations. Perhaps they will invest in more capital equipment to enable their workforce to produce more per hour of their time. Think of a hand car wash installing automatic equipment but retaining the same amount of staff, retraining them to operate the new machinery, and doing more business. This would make minimum wage increases positive for productivity.

Those words ���doing more business��� are important. Higher wages alone might merely induce capital-labour substitution, leading to unemployment rather than higher output. Which is why Ben is right to say higher wages must be accompanied by fiscal stimulus.

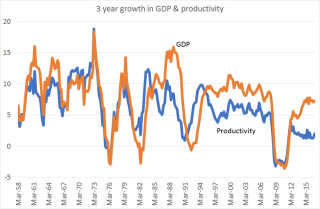

In this, he���s echoing Verdoorn���s law. This says that faster GDP growth is usually accompanied by faster productivity growth.

I���d like to believe this. But I���m not sure I do. For one thing, whilst the Bank of England research Ben cites finds that higher wages can lead to higher productivity, this is the case for only a minority of industries. And for another, Verdoorn���s law hasn���t been so strong recently. My chart shows that whilst there was a massive correlation between GDP growth and productivity from the 50s to the 80s, it hasn���t been so strong lately; productivity has been weak even relative to GDP.

This draws our attention to the possibility that there are several things that might throw sand into the wheels of the mechanism whereby higher wages might raise productivity, for example:

- Uncertainty. If the car wash business is to invest in a new machine, it must be confident that the boost to demand will last. This requires something more than just looser policy ��� be it a looser inflation target, commitment to future easing or whatever.

- Management quality. Do bosses have the skill to introduce new technology well? Bloom and Van Reenen have shown (pdf) that there���s a ���long tail of badly managed firms��� ��� but it is in these where productivity is lowest.

- The fear of future competition. I suspect that one reason why capital spending has been low is that firms fear that their investments will be undercut by future, cheaper ones by their rivals: it���s the second mouse that gets the cheese. It���s not clear that fiscal stimulus will allay these fears.

- Credit constraints. Another reason for low investment is that firms don���t trust banks to keep credit lines open in future. Again, fiscal policy doesn���t address this.

- Weak profits. The hand car wash is probably only just getting by, and so lacks the means and motive to buy fancy kit. The care home sector, for example, is already teetering: why should it respond to higher minimum wages by increasing capital spending?

Now, I don���t say this to dismiss Ben���s idea entirely. Given that the Phillips curve is, to say the least, ill-defined in the UK, the cost of experimenting with fiscal loosening is perhaps low. And even if actual productive capacity isn���t terribly cyclical, estimates of it might be - and they are worth having even if we don���t get a renaissance in productivity. Erring on the side of loose policy seems to me to be better than erring on the side of tight.

The issue here is much bigger than it might seem. The question is: is capitalism cooperative or conflictual? Are the interests of workers compatible with those of capitalists or not? It���s this that divides social democrats from Marxists. Historically, the answer has been sometimes yes and sometimes no. I���m not sure which it is today, but I���d like to find out so I'd like to see Ben's suggestion tested.

April 2, 2017

Brexit as raising the inflation target

Friday���s figures confirming that real GDP grew by 0.7 per cent in Q3 seem to have confirmed Brexiters��� claim that ���Project Fear��� was wrong to have predicted an immediate adverse impact of the vote to leave the EU. There is, though, a point here which both sides are underplaying.

It���s that if we look only at the macroeconomic data, events since June look very similar to what would have happened if the inflation target had been raised last year, or if we���d shifted from an inflation target to a generous money GDP target.

What would have happened if we���d made that shift? The Bank of England would have cut rates, real bond yields would have fallen in anticipation of looser future monetary policy, and sterling would have fallen as a result. We���d also have seen a rise in inflation and inflation expectations. We���d have seen export orders and prices pick up in response to the weaker pound. And we���d have seen consumer spending rise, perhaps temporarily as people pulled spending forward in anticipation of rising prices in 2017, or perhaps permanently because of lower real interest rates.

We���ve seen all of this. So far, therefore, the observed macroeconomic consequences of Brexit look very much like a relaxation of the inflation target.

To a macroeconomist, however, such a relaxation would have been superior to Brexit as it would not have increased uncertainty about future trading rules and so would not have dampened capital spending: the volume of business investment in Q4 was 3.3% down from its peak in 2015Q3.

All of this suggests to me that everybody who thinks that Brexit has been a success so far should have been calling for a relaxation of the inflation target for years. Such a move would have achieved much of what we���ve seen since June, without the downside.

But I'm not sure they did this. Yes, many economists were arguing for such a relaxation. But I get the impression that these were more likely to be Remainers than Leavers. Brexiters were not, generally speaking, among the strongest advocates of changing the inflation target. Perhaps the opposite. To take one example, Ryan Bourne ��� who recently criticized Project Fear ��� has also accused the Bank for being too soft on inflation.

Of course, there is reason not to have wanted such a relaxation, especially recently. For example, if you believe the OBR���s claim that output is more or less at its potential level, you���ll think that such a move would generate inflation more than real growth*.

This, though, is also a reason to doubt the benefits of Brexit because if firms are at full capacity, we���ll not see much increase in export volumes or domestic output in response to higher consumer spending.

This leaves me puzzled. Brexiters who are cheering the economy���s recent strength should also have been longtime advocates of a higher inflation target. Everything the Brexiters are celebrating now could have been achieved with much less palaver by changing the inflation target. But they were much less vocal in that advocacy than they were about Brexit ��� to say the least. This strengthens my view that calls for Brexit weren���t really based upon economics at all.

* Personally, I think the idea of an output gap is silly, but let that pass.

March 30, 2017

Brexit: the state capacity question

Most Leavers want to bring back the death penalty. This confirms Remainers��� prejudices that Leavers are a bunch of social conservatives who want to turn the clock back to 1955. I suspect, though, that there might also be a more interesting division here ��� about attitudes towards the competence of the UK state.

What I mean is that I���m opposed to the death penalty not so much because of romantic notions of human rights but because I just don���t trust the state to distinguish between the guilty and the innocent. I doubt its competence, whereas its advocates are less sceptical.

Similar doubts contribute to me being a Remainer. I���m not sure the Great Whitehall Power Grab ��� David Allan Green���s term for the ���Great Repeal Bill��� ��� will be conducted wisely. I���m not confident that the process of transferring EU law to UK law ��� which has been described as "a civil service legal exercise on a scale that has not been encountered at any other time in our recent legal history" ��� will go at all smoothly. I don���t believe the government can implement immigration controls humanely or efficiently. I doubt that complex trade negotiations can go well, or yield great returns even if they do. I agree with Ian Dunt (who is compulsory reading) that the government���s attitude to Article 50 has so far been ���stupid.��� And the attractions of returning sovereignty to the UK are for me diminished by the likelihood that it will be exercised by buffoons*.

Herein lies an under-appreciated divide between some of us Remainers and some Leavers. On the one hand, some of us are pessimistic about state capacity. On the other, there are Leavers like Dan Hannan who decry our pessimism.

Yes, I know that all of my doubts about state competence could apply as well to the EU itself. But whilst I am a Marxist, I also feel the force of Michael Oakeshott���s scepticism of change (pdf)**:

The conservative will have nothing to do with innovations designed to meet merely hypothetical situations; he will prefer to enforce a rule he has got rather than invent a new one; he will think it appropriate to delay a modification of the rules until it is clear that the change of circumstances it is designed to reflect has come to stay for a while; he will be suspicious of proposals for change in excess of what the situation calls for, of rulers who demand extra-ordinary powers in order to make great changes.

This raises two paradoxes. One is that many Remainers cannot comfortably use this argument. The statist left, for example, needs to believe in state competence. And it cannot hide behind the claim that we would be well-governed if only the right people were in change, as this is silly managerialism.

The other is that the case for Remain I���ve sketched here is a conservative one and yet it is antithetical to the position of very many Conservatives, some of whom look more like fanatical cultists than the melancholy sceptics of Oakeshottian conservatism. Which just reminds us that, as Jonathan says, the Conservative party no longer believes in conservatism.

* I'm not sure my misgivings will resolved beyond everybody's doubt. Everything succeeds by sufficiently low standards, and fails by sufficiently high ones.

** Yes, there might be a contradiction here. But as Niels Bohr said, the opposite of a great truth is another great truth. We should all be capable of having two ideas in our head at the same time.

March 29, 2017

Newt troubles

Why has the UK suffered weak economic growth for years? Is it because falling profits have choked off investment? Is it because there���s a dearth of good innovations? Or because of fiscal austerity? Or because the Bank of England has failed to target money GDP growth? Or because bosses are lazy mediocrities? Or because pessimistic (pdf) expectations have proven self-fulfilling? Or is it because the financial crisis had a long-lasting adverse effect upon the economy?

No, no, no, no, no, no and no. It���s all because of the great crested newt. In its demand to cut EU-imposed red tape, the Telegraph wails:

Under the EU habitats directive, which covers all 28 member states, [great crested newts] are a protected species. If even a small number are found, newts have to be fenced, trapped and relocated in the spring, which can cost ��10,000 even for a small project. In 2011, George Osborne, the former Chancellor, said the directive placed ������ridiculous costs on British businesses.���

Despite the fact that scholars of long-run growth such as Chad Jones, Philippe Aghion and Dietz Vollrath have been silent about them (AFAIK ��� I���d be happy to be corrected) it���s obvious that newts are to blame for sluggish growth.

Economists know nothing: well, what do you expect from so-called experts?

Well, maybe. Or maybe not. I know it���s a longshot, but perhaps ��� just perhaps ��� there���s another possibility here. Maybe red tape isn���t much to blame for weak growth.

One reason for this is that there really isn���t much of it in the UK. Rick says ���the UK is already one of the least regulated countries in the world.��� If you don���t believe him, try the Heritage Foundation, a group not famed for its sympathy for state intervention. It says our ���regulatory environment is efficient and transparent.���

Another reason is that red tape isn���t what holds back economies. There���s pretty much no correlation between labour market regulation and productivity or unemployment.

Why, then, is the Telegraph banging on about red tape and ignoring the many stronger reasons for our economic malaise?

It might be that I���m missing the point. Protecting newts, like laws against bendy bananas, might not have grave effects, but they are examples of the silliness we���ll be rid of when we cast off the yoke of Brussels and bring sovereignty back to Westminster, where it will of course be exercised by wise and all-knowing legislators.

But perhaps there���s something else. For the last 30 years, the right has gotten most of what it wanted ��� lower taxes, weaker unions and less regulation. And yet macroeconomic performance ��� as measured by GDP growth per head ��� hasn���t improved. Their response to this has been a classic example of the backfire effect. As David McRaney says: ���When your deepest convictions are challenged by contradictory evidence, your beliefs get stronger.���

Rather than question their support for ���neoliberalism��� or ��� God forbid ��� doubt the underlying health of capitalism, Tories exaggerate the harm done by remaining regulations. They learn nothing, and they forget nothing.

Worse still, as Brexit negotiations will steal cognitive bandwidth for at least the next two years, we face many more months of this. The great crested newt might be protected, but my patience is not.

March 28, 2017

Keynes' flaws

Michael Roberts reminds us of something important ��� that Keynesian economics has severe shortcomings. I agree.

For me, the problem with Keynes was what he didn���t say. He was largely silent about three related issues: class, power and profits, or least he dismissed them lightly:

the problem of want and poverty and the economic struggle between classes and nations, is nothing but a frightful muddle, a transitory and an unnecessary muddle. (Preface to Essays in Persuasion)

It���s no accident that it should have been so easy to find a Keynesian-neoclassical synthesis, as both schools of thought ignored these matters.

This omission, however, has had several baleful effects.

One is that, in regarding full employment as a narrowly technical matter, Keynes overlooked the fact that capitalists have a powerful interest in maintaining unemployment ��� both because it disciplines workers, and because it gives capitalists influence upon the state to ensure that it maintains business confidence. As Kalecki wrote (pdf):

[Capitalists���] class instinct tells them that lasting full employment is unsound from their point of view and that unemployment is an integral part of the " normal capitalist system.

Post-war Keynesianism broke down in the 1970s in part precisely for this reason: full employment squeezed profits (pdf) which choked off growth.

Secondly, Keynes ���paid even less attention to monopoly power than some of his neoclassical colleagues.���* The possibility that capitalists or bosses would use this power to extract massive rents eluded him. (Again, of course, Kalecki was his superior on this point).

Thirdly, Keynes saw the problem of capitalism as basically one of cyclical swings which are remediable by a few levers of macroeconomic policy. This might have been true once. But as Michael says, it���s doubtful now. Long-term stagnation might require different remedies.

One of these remedies, I suspect, lies in far greater worker democracy.

Which brings me to a fourth problem. In a sense, Keynesianism was profoundly conservative. In believing that technocratic governments could provide workers with decent wages and full employment, Keynesianism did away with the need for industrial democracy: one of the achievements of Keynes was to eclipse movements such as guild socialism. It wasn���t Keynes himself who said ���the man in Whitehall knows best��� but one of his disciples, Douglas Jay ��� and that encapsulated a key part of Keynesian ideology, its belief in top-down management.

Populism, of course, is a backlash against just this. That slogan ���take back control��� and the dismissal of experts represent a rejection of Keynesianism; the baby of decent macroeconomic policy is being thrown out with the bathwater of elitism. It���s far from clear that Keynesianism has the intellectual or political resources to fight back.

Now, at this stage we might channel Leijonhufvud (pdf). The Keynes I���m thinking of here is the capitalist-friendly one. But there���s another Keynes. There���s the Keynes who said that ���a somewhat comprehensive socialisation of investment will prove the only means of securing an approximation to full employment���. And there���s the one who argued in the best chapter in the General Theory that bosses do not and cannot know what they���re doing.

It���s this Keynes that deserves to have a lasting influence.

* Howard and King, A History of Marxian Economics voll II, p101.

March 22, 2017

Martin McGuinness & the nature of politics

James O���Brien tweeted yesterday:

McGuinness was both a murderous terrorist & a powerful force for peace. He changed. Our furiously binary zeitgeist can't compute such change.

I want to expand on this, because it tells us something about the nature of politics generally.

I suspect McGuinness was a force for peace in part precisely because he was a murderous terrorist. Because his credentials as an IRA man were so strong, he could persuade hardline terrorists to give up violence in a way that more moderate republicans could not. Granted, his commitment to peace might, as Padraig says, have been ���tactical rather than principled���. And he might have adopted it from a position of weakness: by the 90s, the IRA was so chocka with MI5 agents that it resembled something from a G.K.Chesterton novel. But peace is peace.

There are many examples in politics of men changing events because their previous commitments gave them credibility with potential opponents of that change. We���ve even got a name for it: ���Nixon goes to China���. Nixon���s impeccable anti-Communist credentials meant that he could begin d��tente in a way that more liberal men couldn���t because of the fear of being labelled soft on communism. Similarly, Tony Blair was able to abandon Labour���s Clause IV in part because he had the support of John Prescott, a man whose deeper roots in the party gave him more influence over Labour traditionalists than Blair alone could enjoy.

Perhaps a closer analogy with McGuinness���s change, however, is the role Lyndon Johnson played in the passage of the Civil Rights Act. LBJ was a racist ��� certainly by today���s standards and perhaps even by those of his time. Such attitudes, however, gave him influence with southern segregationists that Kennedy ��� who had proposed the Act ��� never had. LBJ thus managed to force the Act through Congress whereas Kennedy failed. JFK might have been more acceptable to decent people, but LBJ did the job.

LBJ was both a racist and an advancer of blacks��� rights, just as McGuinness was both a murderer and a force for peace. And both men were one because they were the other.

George Bernard Shaw famously said that ���all progress depends upon the unreasonable man*.��� This might be an exaggeration, but one way in which it is true is that the unreasonable man can persuade other unreasonable men in a way that moderates cannot.

It���s in this context that James is right to decry our simplistic ���binary zeitgeist���. Many people think of politics as a low-grade morality play in which good people ��� people like us, naturally, because we lack the faculties of self-criticism ��� oppose bad people. But it isn���t always so. McGuinness and Johnson show that ���bad��� people can sometimes do good things, perhaps even for bad motives. And the converse can also be true: good people can do bad things. The social sciences are often complex emergent processes: outcomes aren���t always reducible to individuals��� intentions.

Personally, I���d like to see less moral posturing and tribalism in politics and more inquiry into how to build structures that increase the chances of bad people doing good things and lessen the chances of good ones doing bad things. But this is a forlorn hope.

* It���s sort of fitting that Chuck Berry should have died in the same week as Martin McGuinness, as he ��� in his very different way ��� is another example of how dubious characters can do great things.

March 21, 2017

Incentivizing politicians

There���s a link between two of the biggest political stories of the last few days: David Davis��� admission that he hasn���t yet done a calculation of the costs of the UK leaving the EU without a trade deal; and George Osborne���s getting a ��200,000 a year payoff from a Russian oligarch. Both pose the question of how better to incentivize politicians to act in the public interest.

What I mean is that Davis���s failure to do basic due diligence probably owes more to him pursuing his private interest ��� a desire not to hear evidence that discorroborates his beliefs ��� than to the national interest. And whilst Osborne���s career as Chancellor was an abject failure - he wanted to clear the deficit and keep the UK in the EU, failed in both and the two failures are related ��� he has not suffered financially as a result. Quite the opposite. These are not isolated examples. Brexiters polluted the public realm with lies and racism and suffered no sanction for doing so.

Hence the question: can we better incentivize politicians by ensuring that they suffer penalties for incompetence and dishonesty?

The standard answer here is that elections do this: liars and idiots should suffer a loss of office. This sanction, though, is insufficient. Brexiters gained from their lies, Osborne has profited from being sacked. And the main losers from Labour���s defeat in the 2010 election were not so much Labour ministers as workers who have suffered pay freezes and benefit recipients who have been hounded to death.

Nor, of course, do the media discipline politicians adequately. This isn���t just because of partisan bias. It���s also because of their hideously warped priorities. Hammond���s ���U turn��� on raising NICs has been variously described as embarrassing, humiliating and a disaster. And yet it seems to me to be just what policy-makers should do: swiftly correct what is (only arguably) a mistake before it does real damage. What Hammond should be castigated for instead is pursuing continued austerity in the face of weak expected growth. Yet he gets a free pass here.

I���ll grant that there���s truth in the old clich�� that politicians are motivated by a sense of public service; intrinsic motivations do matter. But can we ensure that extrinsic motivations buttress these?

Frankly, I don���t see how institutional tweaks could greatly improve things. Banning ministers from taking jobs after leaving office would risk deterring competent and younger people from politics. And making them personally liable for bad policy would raise tricky problems of distinguishing between bad luck and bad judgment, would run into Campbell���s law, and would disincentivize radical policies, as ministers would prefer to fail conventionally.

Instead, perhaps we should just recognize that our problem here is exacerbated by two forces.

One is tribalism. We give a free pass to incompetent or dishonest politicians as long as they���re in our tribe. Brexiters aren���t slating Davis for his lack of due diligence, just as lefties overlook Corbyn���s personal incompetence and laziness.

The other is capitalism. High inequality means there���s big money to be made outside parliament for a privileged few. And the desire of financiers, businessmen and oligarchs to ensure that politicians do their bidding means they���ll be happy to pay such money. Lebedev and BlackRock aren���t paying Osborne for his talents, which are scant, but rather to show current and future politicians around the world what riches are available to them if they play nicely.

This poses the questions. Is it possible to remove the influence of money from politics and thus shore up politicians��� sense of public spirit? Given the distorting impact of the media and cognitive biases and errors among voters, would there even be a great gain from doing so? Or might it be that our actually-existing capitalist democracy militates against honest competent politics? Never mind the personal failings of men like Osborne and Davis. The issue here is the very structure of politics.

March 16, 2017

David Davis's strategic ignorance

At the Battle of Copenhagen in 1801, Admiral Hyde Parker sent Horatio Nelson the order to retreat. Nelson allegedly raised his telescope to his blind eye, declared ���I really do not see the signal���, continued fighting and won the battle.

I was reminded of this by David Davis��� admission that the government has done no research on the costs of leaving the EU without a trade deal. In truth, he���s right not to have done so. His critics are guilty of a na��ve error. They assume that our rulers must be well-informed. But this is not the case. Instead, as Linsey McGoey has written (pdf):

Cultivating ignorance is often more advantageous, both institutionally and personally, than cultivating knowledge.

This is true in at least four senses.

One is the sense in which Nelson proclaimed his ignorance. He knew better than Parker what his chances of victory were, so disregarded the order. Being deliberately ignorant of irrelevant or useless things can steel us for battle. I apply Nelson���s principle in my day job. I advise investors to follow simple rules ��� such as sell in May or buy defensives and momentum if you don���t want to be a passive investor ��� and to ignore much else. Obtaining more information can often detract from your performance by leading you to trade on noise rather than signal. Just as some horses run better with blinkers, so some people think better with them.

Davis is doing a similar thing. If you regard Brexit as an intrinsic good, you don���t need to know its consequences. And if you distrust experts, you���ll regard their estimates of those effects as noise rather than signal.

A second sense originates from Thomas Schelling���s observation (pdf) that ignorance can be an asset in bargaining.

Let���s say Davis had good research which showed that the cost of a hard Brexit was high. The government could not then credibly threaten to walk away from negotiations with the EU, as the EU just wouldn't believe the government would damage the economy so much. Without such research, though, this threat becomes more credible. The government���s bargaining power is thus strengthened. Nobody messes with the local psycho.

A third sense in which ignorance works is a clich�� of all conspiracy dramas: the ability to maintain plausible deniability. Back in 2012, the House of Commons Culture, Media and Sport Committee accused James Murdoch of an "astonishing lack of curiosity" for not wanting to know about the extent of phone hacking at News International. But there was nothing astonishing about it at all. Bosses who are willfully ignorant of what their underlings are up to can avoid appearing complicit in their misdeeds.

Ms McGoey says we saw the same thing in the run-up to the financial crisis: banks��� bosses had no desire to know the riskiness of what they were doing, and even sacked those who warned of such risks:

Ignorance has a double usefulness. First, widespread social silence enabled the perpetuation of highly profitable, however ultimately destructive, activities. Second, earlier silences were exploited in order to exonerate the actions of individuals claiming risks were impossible to detect. It was logical to claim ignorance both before and after the collapse.

Again, Davis is pulling the same trick. If there���s no official evidence now that a hard Brexit would be a disaster, then if this turns out to be the case he can claim that nobody ��� or at least nobody of any consequence - warned him.

Fourthly, wilful ignorance can be a way of maintaining a healthy self-image. As Donald Davidson has written:

Both self-deception and wishful thinking are often benign. It is neither surprising nor on the whole bad that people think better of their friends and families than a clear-eyed survey of the evidence would justify���Spouses often keep things on an even keel by ignoring or overlooking the lipstick on the collar (in Elster, The Multiple Self, p86)

Nobody wants to believe he is a stupid idiot whose cherished lifelong beliefs are wrong. We avoid this fate by ignoring relevant evidence.

My point here is a simple one. The idea that rulers ��� bosses or politicians ��� should be well-informed is inconsistent with the first rule of economics, that people respond to incentives. Incentives dictate that, quite often, ignorance is better than knowledge.

March 15, 2017

Deregulation fantasies

Several people on Twitter yesterday reminded us of Liam Fox���s vision of a deregulated labour market:

we must begin by deregulating the labour market. Political objections must be overridden. It is too difficult to hire and fire and too expensive to take on new employees.

This fits in with Tory fantasies of the post-Brexit UK being like Singapore.

It does, however run into a problem ��� that there���s no obvious benefit to deregulation.

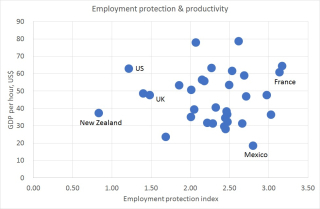

My chart shows the point. It plots labour productivity in 2015 against a measure of employment protections in 2013-14: I���m taking a simple average of four OECD indices of protections again dismissals and regulation of temporary work.

It���s clear that, across 33 countries for which we have data, there is no correlation. It���s also clear that this fact is robust to outliers. Yes, the US has weak regulation and high productivity. But the UK and New Zealand have weak regulation and moderate productivity, which France and Belgium have high regulation but also high productivity.

You might think this is counter-intuitive. Common sense says that if firms can easily fire people then workers��� incentives to work hard are sharpened by a greater fear of the sack, whilst companies can more easily adjust their workforce to changes in market conditions.

These mechanisms, however, are offset by others, for example:

- If people fear the sack, they���ll not invest in job-specific skills but rather in general ones that make them attractive to future employers. They might also spend less time working and more time looking for a new job.

- A lack of protection will encourage people to change jobs more often, as it���s better to jump than be pushed. This can reduce productivity, simply because new workers often take time to adapt to their new company���s clients, IT systems and to new colleagues.

- If firms know they can fire at will they���ll devote less effort to screening or training, and so there might be worse matches between jobs and workers.

Deregulation might be good for bad employers who want to be petty tyrants, but it has no obvious aggregate benefit.

I don���t say this in the hope of changing anybody���s mind. As Jonathan Swift said, ���it is useless to attempt to reason a man out of a thing he was never reasoned into.��� And as Nick points out, Brexiters are a cult that���s immune to reason. But things are true whether or not you believe them.

March 14, 2017

Coping with the backfire effect

Jeremy Corbyn has been getting a lot of stick recently, much of it justified: he seems to be the Henry VI of our time ��� obsessed with his own piety to the neglect of day-to-day politics despite massive and obvious dangers. Nevertheless, he made a very good and important point yesterday (2���24��� in) when he said that the economic debate should be about inequality.

The point here is that the left must shift the agenda onto inequality and capitalist stagnation and away from immigration and Brexit.

I say this because of Tim Harford���s essay in which he points out that facts just don���t matter in political debate.

One reason for this lies in the backfire effect. As Tim says, ���repeating a false claim, even in the context of debunking that claim, can make it stick.���

This means that arguing against (say) the claim that immigrants take jobs is futile. Our arguments might be correct, but they simply bolster the belief that immigration is a problem. I fear the same thing happens when the left ���calls out��� the racism and misogyny of twats like Hopkins and Milo. Doing so merely increases their public profile.

Also, debating immigration is like a game of infinite whack-a-mole. When we knock down one argument ��� jobs (pdf), wages, public services, whatever ��� another jumps up. As Tim says, lies ���summon to mind all sorts of other anxieties���. We���ll never defeat them.

In this context, the impartiality to which the BBC rather feebly aspires is impossible: an ���impartial��� debate about immigration serves the cause of lying racists. As Ed Glaeser and Cass Sunstein said, balanced news produces unbalanced views.

The answer to this is to do exactly what Mr Corbyn says - to change the subject. We should shift the agenda away from immigration towards inequality and stagnation. Doing so would have a two-fold benefit. It would raise the salience of inequality and capitalist failure and so ��� at the margin ��� help change voters��� priors from ���migrants are to blame��� to ���bosses are to blame���*. This would mean the left���s opponents will be fighting on our ground, and so the backfire effect will work in our favour.

It would also change the dramatis personae. Rightist rentagobs have nothing much to say about issues such as inequality and stagnation, so changing the subject will silence them: the more we hear about Sam Bowles and less we hear about Farage, the better.

I suspect this point broadens. For example, my Twitter timeline has given me a very vivid image of what feminists think of Milo, but little idea of who is doing good scientific work on gender inequality. I think that���s a shame.

Such a shift has the tertiary virtue of having an evidence base ��� though I concede that few care about this. The stagnation of real incomes has more to do with austerity, the financial crisis, the decline of trades unions, financialization (pdf) and power than it has with globalization (pdf).

What I���d like to see the left do, therefore, is to do something which we don't do enough of (and I'm as guilty as anyone): we should pay less attention to the worst of the right and give more publicity to the best of the left.

* Strictly speaking, it is capitalism that���s the problem not individual bosses. But emergence is a tricky thing to sell to the media, so it���s tactically better to personalize the issue.

Chris Dillow's Blog

- Chris Dillow's profile

- 2 followers