Chris Dillow's Blog, page 67

January 20, 2017

Economic policy after Brexit

One of my biggest gripes with Brexit is that it is stealing cognitive bandwidth; it���s distracting us from proper economic policies. This is an especial problem for Labour as the party is showing few signs of having much cognitive bandwidth to spare.

There is, though, a big question here: assuming we get a hard Brexit, what should post-Brexit economic policy look like?

Here, we must admit that Philip Hammond���s threat to turn us into a low-tax Singapore-type economy at least answers a good question: how can the UK attract and retain business given that we���ll be offering less good access to the single market than EU nations?

The fact is that we cannot compete on price: Bulgaria and Romania have labour costs which are only one-fifth of the UK���s (pdf).

We could and should, however, compete on labour quality. Post-Brexit, the importance of an educated and trained workforce will be even more important: this means not just university education, but investment in vocational training and early years. We should emulate Singapore in having an educated workforce. In this context, the closure of Sure Start centres should be seen as an act of vandalism, a destruction of the future capital stock.

Hammond might also have point in seeing the need for lower business taxation. However, the answer here might not be so much blanket cuts in taxes and spending but rather a shift in taxation ��� perhaps from profits and incomes to land (pdf). As the Mirrlees review said (pdf), ���there is a strong case for introducing a land value tax.���

It���s also important to encourage the growth of home-grown businesses. In this context, Labour might well press the case for a state investment bank, and for more state involvement in encouraging research and innovation along the lines suggested by Mariana Mazzucato.

A second angle here is that Brexit is likely to compound a massive pre-existing problem ��� that the UK���s productivity has stagnated. Slower trade growth will probably mean slower productivity growth (pdf): it���s no accident that the two have slowed down together since the financial crisis.

In this context, policies to increase productivity will become even more necessary. This too requires encouraging education, capital investment, innovation and new business formation: a lot of productivity growth comes not from incumbent firms upping their game but from new ones entering markets.

The traditional rightist answer to these issues ��� to cut taxes and regulation and so release capitalist dynamism ��� is not sufficient. The fact of secular stagnation tells us that capitalism (perhaps temporarily) has lost its mojo. This points to a need for more interventionist policies.

Thirdly, Labour should acknowledge the power of Vote Leave���s slogan: ���take back control���. However, rather offer the merely formal and legalistic sovereignty that Brexit offers, Labour should consider policies to give people real control. These might include devolution; greater consumer say in public services (pdf); and more worker democracy. The latter, of course, should also be a means of raising productivity.

Finally, we should recognise that there is an economic base to demands for immigration control. Stagnant real wages and faltering public services have hardened people���s hearts to migrants. One solution to this is a reversal of austerity: more spending on public services would raise GDP and real wages, thus eventually increasing toleration of migrants; and it would diminish perceptions that migrants are putting a burden upon public services. And, of course, the continuation of sharply negative real gilt yields means that such policies are feasible and sustainable at least for a few years.

Most of these policies, of course, were good ideas before Brexit - and indeed Labour was thinking along such lines. The point is that, in threatening to depress economic growth, Brexit makes it even more imperative to introduce other growth-enhancing policies. Supply-side socialism should become even more important.

And this should be something Labour can unite around: the right can emphasise the need for better education and training policies, the left co-ops and anti-austerity. Yes, Labour is confused and divided. But there is no logical reason why it must be.

January 19, 2017

In praise of tribalism

Tribalism in politics isn���t always a bad thing.

I���m prompted to say this by the fact that at least one decent Leaver thinks May���s Brexit strategy is wrong. Pete North calls it ���unhinged lunacy��� and a ���clueless gamble.���

Some of us, though, had an inkling of this months ago. This wasn���t because we had greater powers of foresight. Instead, what strengthened my antipathy to Brexit was simply that many of the people who supported it were racists and charlatans. Of course, not all Leavers were by any means. And they had some good arguments, not least about the sclerotic nature of EU institutions. But the fact was that pretty much all racists favoured Brexit. For some of us, this set off the klaxons.

May is interpreting the leave vote as a vote against immigration because that���s what it was for many of the noisiest Leavers. And for some of us, this was precisely the reason to vote remain.

I don���t think that in thinking this way I was committing the ���poisoning the well��� fallacy. The fact that so many Brexiters were racists and buffoons was, to me, indicative of the sort of Brexit we���d get.

Instead, I was being tribal: I didn���t want to be part of a tribe that had a disproportionate number of people I despised. I was using a form of the social proof rule of thumb. I was allowing the numbers of others making their choices to guide mine. The fact that decent people tended to favour remain (with of course counter-examples on both sides) strengthened by support for the cause.

Sometimes, this rule of thumb is good. For example, if you are in a strange city wondering where to eat, the fact that one restaurant is full whilst another is empty might well be a decent guide to their relative merits. In other cases, though, it can be dangerous: asset price bubbles can occur because of the mistaken belief that other people know what they���re doing.

Social proof is an unreliable rule of thumb. What we have in this case, however, might be another example of how biases can cancel out. Had Pete, and other decent Leavers, used this rule of thumb in the way I did, it might have offset their wishful thinking ��� the belief that Brexit would turn out as they hoped. As Gerd Gigerenzer has shown, apparently irrational rules of thumb often lead to the right decisions (pdf).

My point here is of course not about Brexit at all but about the nature of decision-making. In a complex world, our individual rationality can be unreliable. To paraphrase Burke, rather than trade upon our own private stock of reason, we should sometimes avail ourselves of the general bank and capital of nations and of ages. When rid of the toxic assets of racism and dishonesty, that bank and capital told me to favour remain.

January 18, 2017

On Brexit solipsism

Imagine the following scenario. I give you and a stranger an envelope each, one of which contains twice as much money as the other. I then say you can swap envelopes if you give me ��1. Do you do so?

You might think: yes, for the following reason. Let���s say my envelope contains ��10. Then the other contains either ��5 or ��20. So I have a 50-50 chance of losing ��5 or making ��10. This has an expected value of ��2.50. For moderate levels of risk aversion ��� or for those who gamble (pdf) with the house money! - it makes sense to pay to swap.

But having swapped, the same logic suggests you should swap again. And again. And again. And each time, I make a pound out of you. I���ve got me a money pump.

In fact, though, there���s a simple way to protect yourself from this mistake. You should put yourself in the shoes of the stranger with the other envelope. He���s reckoning ��� by the same logic ��� that he should swap envelopes. But if he wants to swap with you, you should reject the offer, because his gains are your losses.

Putting yourself in the other guy���s shoes can therefore save you from losses that can arise from apparently good thinking.

This is no mere abstract thought experiment. One of the strongest stock market anomalies ��� in both the US and UK (pdf) ��� is the tendency for newly-floated shares to do badly in the months after flotation. Investors pay too much for new companies.

One reason why they do so is that they make the same mistake we see in the envelopes problem. They fail to consider the other guy���s position. They don���t ask: ���if this business is worth buying why is the owner ��� who presumably knows more about it than me ��� so keen to sell?��� Asking this would alert investors to the possibility that the company is over-priced and its owners are trying to cash out at the best time.

In both situations, the same mistake is made. David Navon calls it the egocentric framing error ��� then tendency to consider problems only from our point of view rather than the other guy���s.

To put this another way, it���s the failure to distinguish between parametric and strategic rationality. Parametric rationality asks: how can I maximise utility, given particular parameters? Strategic rationality, however, recognises that the parameters aren���t fixed, and that your choice depends upon the choice of the other fellow.

I say all this because I fear that some people might be making the same mistake about Brexit. Looking at much of the reaction to May���s speech yesterday makes one suspect that the UK is the only actor in this drama. But this, of course, isn���t the case. The UK���s demands and strategy is only half the story. We shouldn���t overlook the EU���s position ��� such as discontent with the UK���s ���cherry-picking��� and a desire to ensure that a nation can���t be better off outside the single market than in. In calling May���s position solipsistic, Martin Sandbu is right: she���s looking at it solely from a UK perspective.

In this respect, the tendency towards the egocentric framing error is exacerbated by our traditional insularity (���Fog in the channel: continent cut off���) and monolingualism. As Simon Kuper says:

Foreign countries are opaque to mostly monolingual Britons and Americans. Foreigners know us much better than we know them. This asymmetry probably helped Russia get its favoured candidate into the White House, and it will handicap Britain in the Brexit negotiations.

Perhaps, though, I���m missing the point. Maybe May wasn���t speaking to Europe yesterday so much as to right-wingers here: she���s trying to placate Ukip. In this, she���s continuing a long tradition of treating UK relations with the EU as a by-product of internal Tory party politics.

January 17, 2017

On Brexit over-optimism

Theresa May today said she wanted a ���bolder embrace of free trade��� so that the UK can ���rediscover its role as a great trading nation.��� This echoes Gerard Lyons and Liam Halligan���s view (pdf) that Brexit is an opportunity for the UK to ���trade more freely with nations far more populous and fast-growing [than the EU].��� For me, there are two problems here.

One is simply that free trade deals might not be so easy to arrange. Trump has promised us a ���fair��� deal ��� but ���fair��� is often a euphemism for ���not free���. And as George Magnus has tweeted: ���C'mon Twitter, you think Xi JinPing is the new champion of free trade and a liberal trading order?���

That issue will get lots of attention in coming months.

I fear, though, that it effaces another problem ��� that even if the UK does strike great trade deals, exports might not increase very much. Just because we have the opportunity to do something does not mean we will. I would have thought that Gerard, being a lifelong Fulham fan, would know there can be a distance between opportunity and achievement.

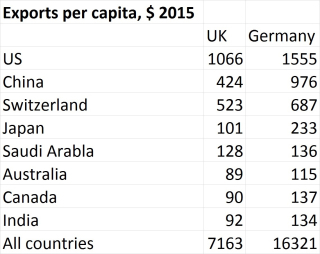

My table gives us a clue about this. It shows goods exports per person to some non-EU countries, taken from World Bank data. You can see from this that Germany exports much more than the UK ��� more than twice as much person to Japan and China, and more to India and Australia, despite the UK���s historic links with those nations.

This alerts us to an important fact ��� that it is not membership of the EU that is holding back UK exports. Germany faces the same trade rules that we do, and is doing much better.

Exactly why this should be is of course a big question. It���s not just that UK businesses are ���fat and lazy��� (to use Liam Fox���s expression). It���s because the UK has for decades lagged behind in skills and investment in some key exporting industries.

Trade performance isn���t just a matter of gravity ��� countries export more to their near-neighbours than to distant countries ��� but also history.

And the thing about history is that it is usually slow to change. This means that even if we do strike great free trade agreements, overall economic growth won���t increase much. Monique Ebell shows that free trade agreements which fall short of really deep integration do little to boost exports.

What���s true for exports is even more true of GDP. In a superb post, Dietz Vollrath shows that most policies have only a small impact upon growth. Even a big rise in potential GDP, he shows, implies only a small uplift to growth simply because actual GDP is slow to converge upon potential*.

And basic maths tells us we won���t get a big increase in potential GDP from free trade deals, simply because exports to most non-EU nations are small as a share of GDP. For example, UK exports to China last year were just 0.7% of GDP. Even if they were to double over a five year period, therefore, we���d get only a 0.13 percentage point rise in GDP growth**.

I say all this to agree with Nick. Brexit ��� at least on the terms proposed by Ms May ��� jeopardizes good existing trade arrangements with the EU in favour of chasing agreements which even if they are reached might not actually benefit us much.

This isn���t just economically risky. It���s also in one sense deeply anti-conservative. Michael Oakeshott famously wrote (pdf):

To be conservative, then, is to prefer the familiar to the unknown, to prefer the tried to the untried, fact to mystery, the actual to the possible, the limited to the unbounded, the near to the distant, the sufficient to the superabundant, the convenient to the perfect.

This, of course, is the precise opposite of what Ms May is offering.

* Yes, GDP can converge quickly towards potential as an economy recovers from a recession. But we���re talking here about changes to trend growth, not cycles.

** In fact, probably much less because we'd have to increase imports to produce those extra exports.

January 16, 2017

Inequality as feudalism

What���s wrong with inequality? This is the question posed by Oxfam���s claim that eight men have as much wealth as the poorest half of the world���s population.

Of course, you can quibble with this: if we look only at net financial wealth, someone starting work at Goldman Sachs with lots of student debt is one of the world���s poorest people and poorer than an Indian beggar who���s just got one rupee. Such quibbles, however, are irrelevant. As Oxfam point out, a lot of the indebted are genuinely poor. And if we consider human capital as wealth (as we should) there remain massive inequalities, not least between our Goldmans trainee and the world���s poorest.

So, what���s wrong with this? We should distinguish between economic and moral arguments against inequality. The economic objections are that high inequality is often a sign of economic dysfunctions such as malfunctioning markets, restrictive intellectual property laws and crony capitalism or that it can be a cause of worse economic performance and increased distrust.

I suspect, though, that the strongest argument against global inequality isn���t so much the economic as the moral one. Global inequality ��� especially when accompanied by absolute poverty ��� means that people are suffering through no fault of their own but simply because of the bad luck of being born in the wrong place. Someone born in sub-Saharan Africa will earn much less than someone of similar talent born in the UK; as Herbert Simon argued, most of our incomes we owe to the good luck of being born in the right place. And they face greater health risks too, especially if they are a woman.

Such inequalities violate the principle of luck egalitarianism. And given the shortened and impoverished lives the worst victims of such back luck suffer, they might well represent a violation of human rights (big pdf).

The case for global redistribution is simply that it is a means of rebalancing such bad luck. Those of us who won the birth lottery should share our good luck with those who lost ��� not least because the losers never asked to enter the lottery in the first place.

This, though, is exactly what we don���t see. One way to pool such luck is overseas aid. But there���s recently been a backlash against this in the trash papers. This isn���t, I think, because people believe Rawlsian law of the peoples-type arguments (pdf) for prioritizing domestic over global redistribution*. Most people who are opposed to higher global redistribution don���t favour greater domestic redistribution. Instead, the Daily Mash called them right:

We need to look after our own first, say people who would never help anyone

But there���s another way of balancing the massive differences in global luck ��� open borders. Allowing people to move from poor to rich countries would greatly relieve their poverty. But again, we���re seeing a backlash against this.

Now, I can of course see practical objections to open borders and global redistribution ��� I���m not completely stupid ��� but I���m not at all clear how robust the moral objections are.

In fact, what such objections amount to is a belief that one���s fate in life should be determined by one���s birth. This is a form of feudalism. Unless public attitudes change very much in the west, feudalism might outlive capitalism.

* Even Rawls believed we have a duty to help ���burdened societies���.

January 15, 2017

On Tory "competence"

A poll in the Independent shows that voters think Theresa May and the Tories would do a better job than Jeremy Corbyn of managing the NHS. Which poses the question: how can Labour be so weak on what should be its core strength?

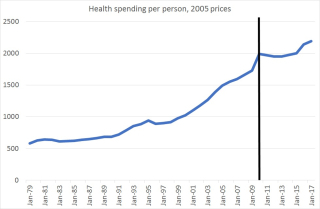

Let���s start with the statistics. Since 2010, real spending per person on the NHS has grown by just 1.3% per year. That compares to growth of 6.3% per year under the 1997-2010 New Labour government. This relative squeeze means that, as Simon Stevens says, there are "clearly substantial funding pressures" on the NHS. It���s surely plausible that, in the absence of policies to greatly improve efficiency, this reduced spending growth might have contributed to the ���humanitarian crisis��� in the NHS.

Why, then, isn���t the government being blamed more?

One reason is that these statistics aren���t sufficiently well known. They���re quite hard to find: I got them from publicspending.co.uk. One reason why they���re not is lies with the atrocious standard of political reporting. This usually consists of ���he says, she says��� claim and counter-claim in which clear facts and ground truth are effaced.

The result of this is that austerity has been presented as an abstract concept which is a matter of debate within the Westminster bubble rather than what it is ��� an act of vandalism which does real harm to real people. Closures of Sure Start centres, prison riots, bad social care, benefit sanctions, flooding and now a malfunctioning NHS are all seen as separate issues rather than what they are ��� the real human damage of macroeconomic policy.

Stalin once said that "if only one man dies of hunger, that is a tragedy. If millions die, that���s only statistics." The Tories are pulling off a similar trick.

But there���s something else ��� the halo effect. Traditionally, Hollywood heroes have been not just better-looking than villains but more charming, smarter and better shots too. This reflects our tendency to assume that if someone has one good quality they must have others. The fact that the Tories are popular for other reasons thus spills over into a belief in their competence even in an area where it is not deserved.

This is magnified by three other tendencies. One is simple deference. As Adam Smith said, we have "a disposition to admire, and almost to worship, the rich and the powerful". A lot of the routine rituals of government exploit this disposition by enhancing what Rodney Barker has called legitimating identities: apparently minor matters such as pictures of Ms May getting out of chauffeured cars, greeting foreign leaders, speaking at a podium with the media a respectful distance away and having speeches trailed as big set-pieces all serve to enhance the appearance of authority.

A second is a trick of Ms May. In being quiet and boring she has allowed the media to assume that she must at least be competent; in this way, she managed to avoid getting blamed personally for the government���s failure to hit its immigration targets despite being Home Secretary.

Thirdly, though, Labour is itself partly to blame. Legitimation rituals and the halo effect work in both directions. If you don���t obey the Westminster rules of politics ��� for example if you speak at rallies rather than do the standard media rounds ��� you���ll not be spoken of as a ���credible��� leader. And if you are incompetent in some respects, you���ll be thought incompetent in others. Voters might well ask: ���If Corbyn can���t manage the Labour party, how can he manage the NHS?��� Whether the blame for this lies with the media, recalcitrant MPs or Corbyn himself is of course a matter of debate. In this debate, however, facts can be ignored.

January 14, 2017

Work, capitalism & retirement

In the Times, Janice Turner cites Freud���s saying ��� that ���love and work are the cornerstones of our humanness��� ��� as a reason for people to continue to work into old age to avoid the ���void��� of retirement. This is both na��ve and depressing.

It���s na��ve not just because it misses the possibility (which is slim in my view) that people won���t have this choice because their jobs will be taken by robots, but because it ignores the fact that work is alienating*. As Marx said:

The alienation of the worker means not only that his labour becomes an object, an external existence, but that it exists outside him, independently of him and alien to him, and begins to confront him as an autonomous power; that the life which he has bestowed on the object confronts him as hostile and alien.

This is still true today. Even where jobs aren���t downright degrading and humiliating, many are just futile. As David Graeber has said, one feature of our time is the rise of ���bullshit jobs���. Ms Turner might be right to think that mixing paint in B&Q is useful, but cold-calling people to ask them to claim compensation for car crashes that didn���t happen is not. And even the lucky few in once-good jobs such as law, journalism academia or even finance face worsening working conditions: more stress and less professional autonomy.

Nor is it the case, as Janice claims, that work is necessarily a way of avoiding loneliness. You���re never more alone than in a crowd. Being surrounded by colleagues can simply remind you that you don���t fit in.

My job at the IC is as good as I could get, but I���m nevertheless looking forward to retiring. Doing so will give me more time to read: just as I became a better economist when I changed job description from economist to journalist, so I hope to become an even better one when I retire. And it���ll enable me to write when I have something to say rather than because I need to: one of the oddities of dead-tree journalism is that the amount that need saying always exactly fills the space between the adverts ��� isn���t that a remarkable coincidence?**

Retiring will also give me more time to keep fit (Radiohead���s lyric about ���a job that slowly kills you��� is literally true); learn the lap steel and Appalachian dulcimer; play guitar; bake; read; and garden. I might even find voluntary work.

Which brings me to the massive and horrible error in pieces like Ms Turner���s. It's true that many of us need to work both as a way of self-development and of feeling useful. But it is a horrible non sequitur to infer from this that capitalist labour is necessary to achieve these aims. Quite the opposite: even the better types of such labour can thwart them. People need capitalist jobs for the money - and very often not for any other reason. The beauty of retirement is that it offers an escape from this baleful aspect of capitalism.

And this is what I find depressing about pieces like Ms Turner���s. In failing to see even the possibility that work can be fulfilling outside the capitalist sphere, they assume that capitalist labour is inevitable, unavoidable and unreformable. But it ain���t necessarily so.

* Here���s a description of alienation narrated by Gillian Anderson, which I offer as refutation of the theory that nobody���s perfect.

** Everything you need to know about finance can fit onto a single sheet of A4, and most of that is footnotes to ���split your money between cash and trackers and forget it.���

January 13, 2017

On defences and attacks on economics

In December 2002 the American Economic Review, one of the most prestigious economic journals, carried a paper by Sven Bouman and Ben Jacobsen called ���The Halloween Indicator��� in which they showed that selling equities in May and buying on Halloween had paid off very well. Anybody who had followed this advice would have sold shares in May 2008 and thus saved themselves a massive loss*.

This is not the only way in which economics predicted the crash. In 2007, I warned that a good lead indicator of equity returns ��� foreign buying of US shares ��� was predicting big losses.

In these two senses, economics did foresee the crash. Contrary to Andy Haldane, there was no ���Michael Fish moment���.

So, does this mean I agree with David Miles that economics has done just fine?

No.

For one thing, these two examples suggest that he is wrong to say that crises are ���virtually impossible to predict���. They did indeed predict a crisis. They suggest that aggregate stock markets are not wholly rational. Such a view isn���t terribly heterodox: it was Paul Samuelson, the granddaddy of orthodoxy, who said stock markets were ���"micro efficient but macro inefficient**."

We must distinguish here, however, between explanation and prediction. As Jon Elster stressed, these are two different things. These indicators predicted a crisis, but didn���t explain it.

There is, though, a second reason why I disagree with David. His correct claim that standard economics has models of crises and bank runs overlooks the fact that, as Dani Rodrik says, the art of economics lies in applying the right model to the right situation. And many economists failed to do this in the md-00s. Rather than point to increasing bank leverage as a potential cause of trouble, they were talking of the ���great moderation.��� And they perhaps focused too much on DSGE models that explained stability ��� or at least regarded shocks as exogenous ��� and too little upon Minsky-type models in which crises were endogenous.

However, although I���m unhappy with some defences of economics, there���s something about attacks upon the subject that troubles me.

Quite simply, economists were not, for the most part, responsible for the 2008 crash ��� except perhaps insofar as their talk of the great moderation emboldened banks to take more risk. It wasn���t us, for example, that said it was a good idea to take over ABN Amro (quite the opposite!). Instead, the crisis was caused by bankers. Criticisms of economics deflect attention from this truth ��� and in doing so, they serve a reactionary function.

* Updated and ungated pdf here. The rule would have meant missing out on decent profits in the summers of 2003 and 2005, however ��� although the UK market performed as well as cash in 2004, 2006 and 2007.

** Actually, the defensive and momentum anomalies suggest they aren���t wholly micro efficient either, but let that pass.

January 12, 2017

No comfort from falling inequality

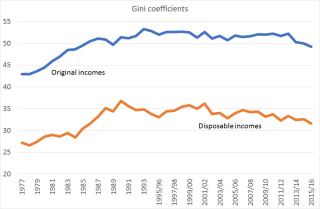

The ONS reports that inequality, measured by Gini coefficients for both pre-tax and post-tax incomes, has fallen slightly in the last ten years. I fear this is an example of how statistics sometime don���t tell us very much.

- Even if inequality is now falling, the damage done by the previous rise in it still lingers. To paraphrase Joseph Schumpeter, if a man has been hit by a lorry you don���t restore him to health by reversing the lorry. And this damage is considerable. It consists not just of slower economic growth but of increased distrust and coarsened politics: the oft-heard allegations that "elites" are out of touch with the ���people��� are the product of that earlier rise in inequality.

- ONS data tell us nothing about the incomes of the super-rich. But we know that the salaries of CEOs of big companies have risen far faster than average incomes, as have incomes of richer bankers. Rising incomes of the super-rich are consistent with a flat or falling Gini if inequalities between the moderately well-off and moderately poor narrow ��� as has happened.

- The same Gini coefficient can describe very different economies. A bourgeois society in which many are doing OK whilst only a few are very poor or very rich can have the same Gini as a winner-take-all society in which some have massive incomes whilst there���s income support for the poor but a hollowed-out middle class. But these will be different societies with (ultimately) different cultures. I suspect that the stable-ish Gini hides the fact that we���ve shifted from the former to the latter.

- Gini coefficients tell us nothing about how inequality arises. The same Gini might arise from people happily paying a man for his great talents (as in Nozick���s Wilt Chamberlain example) or from that man ripping people off. What troubles some of us is that our current inequality is due a lot to the latter.

- It���s not just inequality of income that matters. Inequalities of status and power also do ��� not least because they contribute to bad decision-making and degrading working conditions. These are very much still with us.

My point here is a trivial one. We should ask of all statistics: what exactly is it that these are telling us, and what aren���t they? I fear that inequality statistics might not be telling us much. Of course, my concerns about the causes and effects of inequality might be mistaken. There���s a debate to be had here, but it won���t be settled by the ONS���s data.

January 11, 2017

On wage ratio policies

Jeremy Corbyn���s call for ���some kind of high earnings cap��� on high pay has its flaws. But it���s potentially a good idea.

The first flaw in it is that it���s lousy presentation, and suggests Corbyn���s team have learned little from behavioural economics. A wage ceiling allows lackeys of the rich to whine that Labour hates the well-off. We should reframe the policy. Rather than say nobody should earn (say) 20 times more than the lowest earner we should say that nobody should earn less than one-twentieth of the top earner. We should call the wage cap a wage floor.

The second problem is that a blanket wage floor is too blunt a policy. It doesn���t distinguish between different types of inequality. Some wage inequalities might be tolerable on economic grounds* if they are rewards for great service. This might be the case for entertainers, sportspeople, innovators and even, I���ll concede, some good managers. Other inequalities, though, arise from rigged markets, cronyism and exploitation. It���s these we should most want to abolish. But a simple legal wage floor hits all inequalities indiscriminately, as do higher taxes. That���s sub-optimal.

There are, though, solutions here.

One possibility, as Corbyn says, for the wage floor to apply only to government contracts. Here, the problem of deterring innovation isn���t so great: what matters is that contracts be sufficiently well-written to avoid agency problems. A wage floor would help disincentivize the rent-seeking that accompanies outsourcing.

A second possibility is to have worker and/or consumer representatives on remuneration committees for larger firms. If a manager or innovator adds great value, the dispersed wisdom of crowds should recognise this and so accept a high wage ratio. But where managers are mere rent-seekers, the committee will rein in his pay.

It���s possible that these mechanisms will actually stimulate the free market that rightists (often insincerely) claim to want. If a manager thinks he has great talents which aren���t sufficiently rewarded by a cap on wage ratios, he should set up his own business where the wage cap doesn���t apply**. In this way, a wage floor might actually incentivize entrepreneurship.

I���d add three other observations:

Corbyn is right to identify inequality as an issue. The fact that productivity has stagnated after an increase in inequality should alert us to the likelihood that inequality is indeed bad for growth.

Measures to tackle wage inequality, however, are not sufficient. Inequality of pay is a symptom of inequality of power ��� and this is an under-rated problem.

What we want here are policies that are stepping stones towards more socialist ones. For example, a cap in inequalities in companies getting government contracts might encourage the growth of co-ops. And greater worker representation on remuneration committees might lead to demands for more worker power in other dimensions. Blind statist policies might be a dead-end, but more flexible and empowering ones might not be.

* We should distinguish between economic and moral objections to inequality. Even if inequalities arise in a perfectly free market and have no adverse economic effects, there might still be philosophical objections to them from, for example, luck egalitarians.

** If worker/consumer-dominated remuneration boards only applied to firms employing more than 250 people they would cover only 0.4% of companies. This would provide a very big sector where bosses could earn as much as their talents would permit.

Chris Dillow's Blog

- Chris Dillow's profile

- 2 followers