Chris Dillow's Blog, page 71

November 6, 2016

Knowledge vs rationality

One question posed by Jason Brennan���s Against Democracy is: who should be the epistocrats?

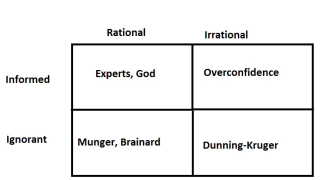

Ideally, of course, they would be informed and rational. But these are two different things. Which means we have four categories of people* as my diagram summarizes.

In the top left we have the informed and rational. These are proper experts (who might, of course, be only a subset of those who appear to be expert). But here���s a problem: there are no general purpose experts. Some of you might think I���m tolerably rational and informed about a few economic issues, but I���m ignorant about foreign and legal affairs ��� just as experts on those might know little about economics. This is a problem, as people who are rational and informed on some matters can be as daft as a brush in other contexts.

In the opposite corner we have the ignorant and irrational. Perhaps the most dangerous of these are those prone to the Dunning-Kruger effect: those who don���t realize that they are ignorant.

It is, however, the other corners that interest me. In the top-right we have the informed but irrational. These include some people whose perhaps genuine expertise in one field emboldens them to consider themselves more general experts; think of dinner party bores and some guests on the BBC's moron-yak shows.

But there���s another group in this category: people who are befuddled by their own knowledge. Take two examples from investing. Even financially literate and intelligent retail investors make expensive mistakes, such as trading too much or investing in poorly-performing high-charging funds. And even quite short runs of good returns can make investors ���dizzy with success���: their good performance emboldens them to take too much risk. In such cases, moderate knowledge creates an illusion of knowledge and overconfidence.

This can happen in politics. Thatcher���s successes (by her own lights) in the 80s led her to introduce the poll tax, which destroyed the Tories in Scotland for a generation and contributed to her losing her job. And Blair���s successful interventions in Kosovo and Sierra Leone led him to think he could repeat the trick in Iraq.

In the opposite corner from these, we have those who are rational but ignorant. Exemplars of this include Charlie Munger and Warren Buffett. One of their strengths is that they know their ���circle of competence��� and try not to stray outside it. This means they avoid lots of businesses which they don���t understand but stick to principles they know that work ��� namely, using (pdf) their insurance float to take cheap geared positions in defensive stocks, a trick retail investors can only half-emulate.

Another example of rationality and ignorance is the Brainard principle ��� the idea that, faced with uncertainty one should do less than one otherwise would. Although this is associated with monetary policy it has wider relevance. For example, if I were conducting foreign policy I would set an extremely high bar for engaging in military action. Such a rule would risk not intervening in cases where one could do good. But it would avoid catastrophic engagements.

The general idea here is that the rational but ignorant stick to rules which require inaction in many circumstances.

This brings me to a problem with epistocracy: what if true experts are scarce? One danger is that if you call some people ���epistocrats��� they���ll believe they are experts when they are not and so commit the errors that arise from overconfidence.

Personally ��� given the choice in a second-best world - I���d prefer rulers to be rational but ignorant than informed but irrational. But this poses the question: do we have the rules and institutions that best mitigate the problems that arise when informed rationality is absent?

* Of course, there isn���t a sharp divide between rational and irrational or between the informed and ignorant: we lie on a spectrum between the two. I���m simplifying.

November 4, 2016

Against Democracy: a review

Should everybody have a right to drive? Most of you would say not. Some people are incompetent, reckless or drunk drivers who endanger others. They should be kept off the road for everyone���s safety.

Jason Brennan���s argument in Against Democracy is that what���s true of driving is also true of voting. Some voters are so irrational and ill-informed that their preferences endanger the rest of us. Just as we have a right to be protected from bad drivers, so we should be protected from bad voters. He favours epistocracy ��� rule of the knowledgeable ��� over democracy.

I find his argument only half-convincing. He���s strong at showing just how badly informed voters are. He���s also good at undermining the conventional arguments for a right to vote. For example, because your vote almost certainly won���t affect the outcome of an election, you lose no power by being denied a vote. Nor are your rights of self-expression limited: you can express yourselves in countless other ways.

What���s more, he says, political expression often brings out the worst in us. He cites Shanto Iyengar and Sean Westwood���s research (pdf) which shows extreme polarization between Democrats and Republicans, but a moment spent watching Question Time would also vindicate him.

Nor, he says, would unequal voting rights undermine equality of status. For example, I might know more about economic policy than my plumber. But this doesn���t and shouldn���t mean I���m a better person than him, any more than his superior knowledge of plumbing makes him my superior. Brennan says:

We should stop viewing the right to vote as a badge of equal status and instead regard it as having no more symbolic power than a hunting or plumbing licence.

Brennan is also unworried by the possibility that an unequal franchise would give more votes to (say) richer white men than to black women. For one thing, he says, if this is the case it���s the product of past injustices and is an argument for rectifying those.

I���m unsure of this. Certainly, the fact that gender, class and racial injustices have persisted for decades after women, workers and blacks have had the vote suggests that universal suffrage isn���t sufficient to achieve justice. But might it be necessary? Brennan thinks not. He argues that people don���t vote in their self-interest, so under-represented groups would be protected by others. I'd prefer stronger safeguards.

Where Brennan is persuasive, I think, is in arguing that our right to competent government is stronger than a right to vote. As he says:

Just as it would be wrong to force me to go under the knife of an incompetent surgeon or sail with an incompetent ship captain, it seems wrong to force me to submit to the decisions of incompetent voters.

However, I have two big gripes with his theory.

One is that he seems vague about the form of epistocracy.

One possibility he suggests is that voters should set ends and informed politicians should choose means, as a man might tell a ship���s captain his destination but allow him to choose how to get there. For me, this doesn���t work. What if the ends are unattainable? And is there a distinction between ends and means? For example, is Brexit an end in itself or is it a means?

Another possibility is that bad candidates whom the voters choose can be vetoed by an ���epistocratic council.��� This seems impractical. Can you imagine what would happen if Trump were to be elected president but an ���elite��� were to prevent him taking office?

Merely raising this question highlights a virtue of democracy which Brennan under-rates: it is a way of keeping the peace by placating the mob.

We might, however, read Brennan in a different way. Our actually-existing democracies have in fact always had epistocratic elements. In a parliamentary democracy our elected representatives should exercise superior judgment on our behalf. (And if they don't, that's because epistocracy doesn't go far enough). And independent institutions ��� such as central banks and the judiciary ��� help to prevent bad choices. One can read Brennan as a defence of these epistocratic institutions against referenda and populist sentiments. And this makes his book so very valuable now.

November 3, 2016

"The will of the people"

Brexiters��� reactions to the High Court���s ruling that parliament must vote before the government invokes Article 50 give us a clearer idea of what they meant by ���taking back control.���

Dominic Raab says the ruling is ���a plain attempt to block Brexit by people who are out of touch with the country.��� Nigel Farage speaks of ���betrayal��� ��� and just look at some of the comments he attracts. And Suzanne Evans says:

How dare these activist judges attempt to overturn our will? It's a power grab & undermines democracy. Time we had the right to sack them.

���Taking back control���, it seems, means that the will of the people ��� as they interpret it ��� must not be constrained by the judiciary or parliamentary scrutiny. Evans��� demand to sack judges should be seen in the context of opposition to the independent Bank of England and the demand that Remain ���traitors��� be ���silenced���. They are totalitarian demands to quash opposition or independent scrutiny.

This runs into several problems. One is that they just aren���t true. As Jolyon points out, a parliamentary debate will actually plug a democratic deficit by revealing what Brexit means.

Also, the Brexiters���s whines are unBritish. They are alien to our traditions and constitution, which recognise the independence of the judiciary and that it is parliament that is sovereign, not the ���will of the people���. The High Court���s ruling was an assertion of ���the fundamental constitutional principles of the sovereignty of parliament.���

I���d add that the Brexiters are also anti-Thatcherite, as she was opposed to referenda. In 1975 she said:

Our system, which has been copied all over the world, is one of representative Government under which those who have not time to look into every detail of this or that Bill choose people who are honourable and with whose opinions they are in harmony to discuss these matters. That has been our system of Government for many years, representative Government in which the representatives consider and discuss all the points in detail. In a popular vote, the voter expresses an individual opinion. In a representative institution, the representative would be expected to consider the interests of minorities and see how the separate measure fitted into the whole. I believe that if we have a referendum system, minorities would not receive anything like such a fair deal as they have under the existing system.

Which brings us to a paradox. Since Thatcher said that, there���s been mounting evidence that voters are ill-informed ��� not just about the EU but about everything - and irrational: they are prone to more cognitive biases than you can shake a stick at. Yes, there are conditions under which crowds can be wise, but these are only occasionally satisfied.

You���d expect, therefore, to see less respect now for the ���will of the people��� and a greater valuation of the separation of powers and of forms of rational deliberation which parliament can ��� albeit only very occasionally ��� provide. Thatcher���s position should therefore be stronger now than it was then.

So why isn���t it?

The answer, I fear, lies in a deterioration in the British character. Many of us (and not just Brexiters) have become narcissistic over-entitled fanatics. Like spoiled children, they scream and scream ���I want, I want���, oblivious to the fact that such wants require rational scrutiny.

This is not an environment in which serious politics is possible.

November 2, 2016

Socially influenced preferences

This morning, Jo Michell tweeted:

Preferences are mostly socially determined. i.e. the opposite of what the textbooks say.

In a general sense this is trivially true. No middle-aged Victorian gentleman wanted a Martin guitar or Brennan B2 as one of their 21st century counterparts does.

However, we have lots of finer-grained evidence on this point.

Some of it comes from investment decisions. Common sense, and standard financial advice, says that these should depend upon individuals��� taste for risk. But there���s more to it than this.

Some experiments by Matteo Ploner and colleagues established this*. They offered subjects choices among bets, and found that when the subjects were told what the average choice of others was, they moved towards that choice.

This experiment has external validity. Hans Hvide and Per Ostberg show that people own similar shares to their colleagues, and when they change job, they buy shares similar to those owned by new colleagues. This isn���t because their colleagues know something they don���t: such shares do not out-perform. Other research suggests that herding is more common with investors who have suffered recent losses, suggesting that doubts about one���s own competence lead people to follow the crowd. In a similar vein, Ben Jacobsen and colleagues show that peer effects are a bigger influence upon asset allocation decisions than individuals��� personal circumstances.

We also have evidence that consumption decisions are partly socially determined. US research suggests there is a ���keeping up with the Jones��� motive. And some nice Dutch research shows that when someone wins a car in a lottery, his neighbours are disproportionately likely to buy new cars for themselves.

We have plenty more evidence. Experiments suggest that the choice of how hard to work is influenced by peers. So too are decisions about one���s health ��� people are more likely to be obese if friends and neighbours are. And so too are educational choices such as what (pdf), where (pdf) and how much (pdf) to study.

What are the mechanisms here? One possibility is that people just want to fit in. Another is that our perceptions of what���s true are shaped by others. The latter, however, can badly mislead us: Solomon Asch���s study found that people���s decisions about a trivially obvious question ��� the length of different lines ��� can be influenced by others. This paper (pdf) suggests that both mechanisms can be important.

In saying all this, I don���t intend to say that our preferences are wholly or even, as Jo claims, ���mostly��� socially determined: in Asch���s experiments, only a minority of subjects either always or never conformed.

Nevertheless, the evidence is sufficient to suggest that people���s choices might not reflect their best interests. And this brings into doubt not just conventional welfare economics but also some justifications for democracy.

* I know some of you have doubts about the relevance and replicability of experiments. But in this context they have a great virtue, of allowing us to overcome the problem that people acting similarly might be due to a ���like attracts like��� effect rather than a pure peer effect.

November 1, 2016

On the counting heuristic

Simon asks for a sense of proportion about the allegations of Hillary Clinton���s misuse of emails:

The media obsesses over whether Clinton might have sent an email containing confidential information from her personal account while secretary of state, and also wonders about whether Trump tells lies, pays any taxes, bribes officials and assaults women. Anyone who reads these stories can see that there is no equivalence here. But anyone who just reads the headlines would be tempted to think otherwise.

There might be a more widespread cognitive bias at work here. We can call it the counting heuristic ��� a tendency to judge things by frequency rather than impact. Here are three examples:

- A lovely paper by Michael Ungehauer and Martin Weber shows that people evaluate correlations between asset returns simply by looking at the frequency of co-movement. This can lead them to under-estimate correlations by putting too little weight upon a few large moves. But in risk management it is these moves that matter: a stock that falls only slightly when markets slump is worth having. Neglecting this causes defensive stocks to be under-priced.

- In the mid-00s, a long run of stable returns led banks to presume that mortgage derivatives were relatively safe. They therefore under-estimated tail risk ��� the small chance of disaster. Investors and corporate managers can under-estimate the importance of low-frequency, high-impact events in non-financial firms too.

- The peak-end rule tells us that we look back more fondly upon a nasty experience if it is followed by discomfort than if it suddenly ends. For example, colonoscopy patients who had the scope left in for a few minutes at the end of the procedure evaluated their experience as less unpleasant than those who had it immediately removed. In this way, the duration of an experience can mislead us as to its impact.

These experiences all imply that a steady drip-drip of minor allegations such as those against Clinton can weigh more heavily in people���s minds than more serious allegations ��� just as the drip-drip of small co-movements distracts people from important large co-movements, or frequent small returns distract people from the risk of big losses, or a frequent discomfort can cause them to misremember real pain.

One simple question should help us combat the bias generated by the counting heuristic. Just as the first question you must ask of any statistic is: is that a lot or a little? So we must always ask of any news story: so what?

Size matters. For example, the countless stories about Clinton���s misuse of emails (which might be exaggerated by the error of correlation neglect) pose the question: is a neglect of bureaucratic protocols really more serious than tax-dodging and sexual assault?

This over-weighting of frequency and under-weighting of impact has also infected UK politics. Here are four examples:

- In the 2015 election campaign there were numerous stories about the ���cost��� of Labour���s policies. Such stories generally failed to point out that these costs were much smaller than the cost of Tory austerity.

- The frequency of stories about benefit fraud obscures the fact that the ���cost��� of such fraud is in fact low ��� and in fact, is often a transfer from tax-payers to companies or landlords.

- Tory attacks on the Bank of England pose (but do not answer) the question: even if we grant that there have been monetary policy errors, how big are these relative to the cost of fiscal policy errors or Brexit?

- The tabloids��� fuss about some migrants falsely claiming to be children raises the question: so what if we let into the country a few 20-something refugees?

My point here should be a trivial one ��� that quantification matters. However, the interaction of a vicious media with cognitive biases means that even trivial points get neglected in politics.

October 31, 2016

Selecting for fanaticism

I���ve long thought that the problem with politics isn���t just what people believe but also the fanaticism and dogmatism with which they believe it. Tory attacks upon Mark Carney illustrate this fact.

Let���s face it, these are motivated in large part not by the technicalities of monetary policy but by Carney���s warnings before the referendum that Brexit would unsettle the economy. In this sense, they are part of the same mindset that demands that Remainers be lock up as traitors: they are an attempt to silence dissent. That���s a symptom not just of the right���s hatred of freedom, but of fanaticism and hysteria ��� of a belief in one���s cause which is stronger than the evidence warrants.

But of course, fanaticism is not confined to the right. It can be found across the political spectrum - even, I suspect, among people who are sane and reasonable in other respects.

Which brings me to my problem ��� political institutions (including of course the media) select for fanatics. I���m thinking here of (at least) four different mechanisms:

- Fanatics are more likely to contribute a lot to pressure groups and parties, thus raising the salience of their pet beliefs. Anti-immigrationers have Migration Watch. Those of us sympathetic to open borders have no equivalently powerful organization, perhaps because we are less willing to pay big money for it.

- The BBC is more likely to invite partisans onto its discussion programmes rather than those who are more sensible or who see both sides. For example, we hear a lot from the Taxpayers Alliance relative to more sensible economists, and heard rather more from Farage during the Brexit campaign than from more reasonable Brexiters such as Andrew Lilico.

- Fanatics are more willing to lie to support their cause and ��� with the BBC being impartial between truth and lie ��� this gives them an edge.

- Fanatics are often articulate about their cause, because they have so much practice in repeating it and because it���s easy to be fluent if you rarely use the word ���but���. Because people are apt to take overconfident people at their word, this gives them a plausibility they don���t warrant.

If we had rational political institutions, these biases would go the opposite way: fanaticism would be selected against, not for.

For example, one virtue of demand-revealing referenda is that people must say how much they are willing to pay to back a cause. Although the law of large numbers makes it unlikely that people really would have to stump up, such a process forces people to ask: how much do I support this cause? And it would also bring proportion to debates. Imagine if, during the Brexit referendum Evan Davis had been able to ask (say) Farage: ���OK, how much are you willing to pay to leave the EU?���

Also, good institutions of deliberative democracy would select against irrational and over-stated arguments, and in favour of more correct ones.

And a BBC that took seriously its mission to inform as well as entertain would banish fanatics from its airwaves in favour of reasonable people.

But of course, we are miles away from such institutions ��� which means that politics is disfigured by a hysteria we see in few other walks of life.

October 30, 2016

The case for basic income

Two apparently unrelated recent events have something in common: they both highlight the case for a citizens��� basic income.

The first is the ruling that Uber drivers are not self-employed and so are entitled to the living wage and other employment rights.

The logic for this ruling has been expressed by Jolyon. Uber drivers, he says, must accept the terms and conditions of their employer: unlike the traditional self-employed, they cannot set their own prices. They lack market power, and so the law should protect them.

But this protection comes at a price. The higher cost of employing Uber drivers means either higher prices for Uber users, thus reducing consumer welfare, and/or less demand for such drivers thus depriving some of much-needed work.

We have therefore a dilemma. How can we protect workers who lack bargaining power whilst at the same time not stifling new businesses and flexible forms of work?

This is where the citizens��� income enters. In giving people an outside income, it empowers them to reject bad jobs. But it also gives them the flexibility to work a few hours as they please. We thus get the best of the gig economy ��� proper entrepreneurship and flexibility ��� without the worst: egregious exploitation. As the great Philippe van Parijs says:

[Basic income] provides a flexible, intelligent form of job sharing. It makes it easier for people who work too much to reduce their working time or take a career break. It enables the jobless to pick up the employment thereby freed, the more easily as they can do so on a part-time basis, since their earnings are being added to their basic income. And the firm floor provided by the basic income makes for a more fluid back and forth between employment, training and family.

The second development is the film I, Daniel Blake which has highlighted that the welfare state is costly, inefficient and dehumanizing, even driving people to suicide. As Max says:

Welfare in the UK doesn���t work. Claimants aren���t winning ��� they get messed around with sanctions, crap placements and form filling, all of which takes time and energy away from the jobsearch. Frontline DWP staff aren���t winning ��� they have no discretion, they have to deal with claimants presenting complex life issues, and they take a lot of shit from claimants. The public is not winning, because more and more public money is wasted on job centres, Work Coaches, civil servants, the crap Universal Jobmatch system, tribunals, appeals, and the wider social costs of a dysfunctional welfare system.

Again, this highlights the merits of a basic income. Its unconditionality would sweep away a lot of bureaucracy. Welfare recipients win because they no longer face harassment. Taxpayers win because the deadweight cost of redistribution is diminished.

None of this is to say that a citizens��� income is a fix-all. It���s not. It should be accompanied by other policies to improve workers��� job opportunities and bargaining power such as expansionary macro policy, a job guarantee and stronger trades unions. And important questions remain: how do we best overcome the objection that a citizens��� income is ���something for nothing���? How do we deal with the problems of especially high needs among the severely disabled and differences in housing costs? And does a state that has been unable to introduce Universal Credit competently have the capacity to implement such a big and important reform?

If we had serious political discourse, these questions would be properly discussed. But that of course is a big ���if.��� I used to think a basic income was too much to hope for. Now I fear that intelligent debate about one might be.

October 27, 2016

Resisting asymmetric Bayesianism

It���s a commonplace that politics is becoming more polarized and tribal: think of Remainers vs Brexiters or Trumpites vs Clintonites. This isn���t simply because people have retreated into intellectual trenches in which they associate only with the like-minded and get their news only from sources that echo their prejudices. It���s also because of another mechanism which is variously called attitude polarization, the backfire effect or asymmetric Bayesianism.

This is the process whereby people who are confronted with evidence that disconfirms their beliefs do not become more open-minded as Bayesianism predicts, but rather become dogmatic. The earliest evidence on this came from a 1979 paper (pdf) by Charles Lord, Lee Ross and Mark Lepper. They showed people mixed reports on the effects of the death penalty. They found that, after reading these reports people who supported capital punishment became stronger in their support, whilst opponents of the death penalty also became more dogmatic. This arises from a form of confirmation bias: we look favourably upon evidence that confirms our position but sceptically upon disconfirmatory evidence.

Reasonable people lament all this.

But here���s my problem: I find it damnably hard not to be an asymmetric Bayesian. One reason for this is that having learned about cognitive biases I now see them everywhere. Yes, I know ��� that���s the confirmation bias. But of course, it���s easier to see them in others than in oneself: physician, heal thyself.

But my opponents don���t help me. Many who favour tough immigration controls, for example, look like hysterical nativists who don���t even have the wit to recycle Rawlsian law of peoples-type arguments. And many aren���t even trying to convince me; perhaps most political discourse is preaching to the choir rather than an attempt to persuade opponents. (The Left are probably as guilty as the right here).

So, how can I resist the pressure to be an asymmetric Bayesian? Here are four things I try:

- Construct one's own argument for something one doesn���t believe in. I tried this here, here and here.

- Look for weaknesses in your own theory. For example in yesterday���s post, I didn���t establish that people in power actually are racist, but merely expressed scepticism about the validity of other explanations. That wasn���t good enough. (In fairness, though, proof on this matter is perhaps unobtainable.)

- Look for disconfirming evidence. To take yesterday���s post again, I might have pointed out that Indian men earn more than similarly qualified white men. This might be evidence against employer racism. (But is it proof? It���s possible both that Indians sort into high-paying occupations and that they suffer racism which causes their wage premium over whites to be lower than it otherwise would.)

- Look for intelligent arguments against one���s case. The fact that most of one���s opponents are silly and hysterical doesn���t mean they all are. For example, I especially valued this post by Ben Cobley, and welcome the writing of Bryan Caplan and his colleagues or Andrew Lilico.

Of course, in saying all this I don���t claim to succeed in resisting the pressures of asymmetric Bayesianism. No doubt I fail.

But here���s the problem. My efforts to do so arise solely from intrinsic motivations. External incentives actually encourage asymmetric Bayesianism. The MSM select for overconfident blowhards; Toby Young, remember, actually earns a living. And most politically-engaged people on left and right would rather associate with a fellow partisan than a pointy-headed sceptic. When Michael Gove said that the country has had enough of experts, he was in part expressing a truth.

October 26, 2016

Whose racism?

Phil McDuff complains about the portrayal of the white working class as a ���howling mass��� whose ���concerns��� about immigration must be heeded.

This poses a question: why do we hear so much about the racism of the white working class and so little about the racism of the ruling class?

Take the following facts:

- People from ethnic minorities are twice as likely to live in poverty as white people.

- The median net wealth of white British households is almost three times (pdf) that of black Caribbean ones.

- ���Ethnic minorities are still hugely underrepresented in positions of power��� says David Isaac.

- Graduates from ethnic minorities are more than twice as likely to be unemployed as white graduates.

- ���Once personal characteristics have been taken into account, all major ethnic minority groups have lower pay [than whites]��� says Hilary Metcalf.

- Ethnic minorities are ���significantly under-represented��� in top public sector jobs, the arts and creative occupations.

Of course, these might be due to many factors such as differences in cultural capital or occupational sorting. But they might be due in part to racism by the ruling class. Not necessarily overt racism, but also a subtle racism which under-rates and de-prioritizes ethnic inequalities.

What's not to blame for these these inequalities is the racism of the working class*. Hence my question: why do we hear so little about ruling class racism but so much about working class racism?

Certainly, this pattern serves useful functions. It helps to deflect attention away from trends that have hurt workers of all colours such as austerity, the decline of trades unions and power-biased technical change. As Phil says:

Our other ���genuine concerns��� ��� such as school and hospital funding, benefits and disability payments, the crushing of industries that formed the backbones of our local economies ��� are ignored or dismissed out of hand.

It also helps to divide and rule working people, and provide a justification for doing what politicians want anyway ��� to impose immigration controls.

But it does something else. Over-emphasizing white working class racism serves to stigmatize and delegitimate the powerless, whilst under-estimating ruling class racism helps to legitimate those in power. If you think I���m making a Marxist point here, you���d be only half-right. I���m echoing Adam Smith:

We see frequently the vices and follies of the powerful much less despised than the poverty and weakness of the innocent. (Theory of Moral Sentiments, I.III.29)

It���s through means such as this that inequalities of power are legitimated and sustained. And the tragedy is that so many people fall for such old tricks.

* I might be overstating this. It���s theoretically possible that employers don���t hire ethnic minorities because they fear that white co-workers wouldn���t accept them. But I doubt this is a significant factor nowadays. It would certainly be odd if bosses were so mindful of white workers��� attitudes on this point when they are otherwise so contemptuous of them.

October 25, 2016

Blind to costs

One of the more curious recent opinion poll findings has been that people are unwilling to pay to control immigration. A Yougov poll found that 62% would pay nothing to reduce net migration from the EU, and that only 15% would pay 5% of their income to reduce it to zero. Support for immigration controls, it seems, falls away when people are asked to pay for them.

But of course, such controls do have a cost. Although the near-term impact of immigration (pdf) on overall wages (pdf) is roughly zero, it���s quite plausible that tough migration controls would reduce innovation and productivity growth in the longer-run, leaving us worse off. And even if you disregard this, there are shorter-term costs: the deadweight cost of paying for border guards; the loss of export earnings as universities take in fewer overseas students (which should mean a weaker pound and hence higher import prices); and the loss of net tax revenue because migrants make a positive contribution to the public finances.

All this poses the question: given that immigration controls have obvious costs which most people are unwilling to pay, why is support for such controls so strong when people are not confronted with their costs?

One possibility is that voters assume that others will bear the cost. This might be reasonable for the low-paid, non-tax-payers and for older people. But it���s plain wishful thinking for others.

Another possibility is simply that people are lousy at making connections in economics, and so don���t link controlling immigration with costs of doing so.

However, I want to suggest another possibility ��� that the supposedly impartial media is deeply misleading here.

Discussion programmes ��� not just about immigration but anything else ��� tend to follow a strict format based upon the adversarial prosecution-defence model; there���s an advocate of a position and an opponent ��� often with both being overconfident blowhards.

What this misses is that policies have costs. The question is not simply: is this policy right or wrong? But rather: is the cost of this policy worth paying?

So for example, it would be reasonable to support immigration controls because their economic cost is worth paying to shore up social capital. It would also be reasonable to oppose them because you place more weight upon their costs ��� in money and freedom - than to the risks to social capital and of discontent as the popular will is disregarded; this is my position.

Reasonable people should take either position on immigration with a heavy heart.

But this sort of position is often excluded by the adversarial model of discourse which invites only pro- and anti- stances. Such a model encourages fanaticism at the expense of trying to assess costs and benefits. It is yet another way in which the ���impartial��� media actually serves to coarsen discourse.

But there is an alternative. Rather than have a prosecutor-defender model, discussion programmes could have an examining magistrate model in which examining the evidence is more important than having a ding-dong. This might not make for good TV or radio. But the BBC must ask: is it in the business of entertaining fools, or in the business of improving political discourse?

Chris Dillow's Blog

- Chris Dillow's profile

- 2 followers