Chris Dillow's Blog, page 75

September 10, 2016

Meritocracy vs freedom

Theresa May said yesterday:

I want Britain to be the world���s great meritocracy ��� a country where everyone has a fair chance to go as far as their talent and their hard work will allow.

Of course, we lefties don���t like this: we believe a greater equality of outcome is more feasible and desirable than meritocracy. What���s insufficiently appreciated, however, is that Ms May���s vision should also disquiet the free-market right, because meritocracy is incompatible with freedom.

Just think what a true meritocracy would look like.

For one thing, it would require the abolition of private education as we know it, because to a meritocrat it is unjust to allocate school places on the basis of parental income rather than merit. As Ms May complained: ���Where is the meritocracy in a system that advantages the privileged few over the many?��� Of course, there might be a case for abolishing private education. But doing so would be a great reduction in freedom.

Also, meritocracy would require the abolition of family companies, because management jobs in these should go to the best people rather than to family members. And the latter are very often not the best; as Bloom and Van Reenen has pointed out, family-run firms are often especially badly (pdf) run.

For the same reason, meritocracy would mean that friends could no longer do many favours for each other; they couldn���t offer internships or jobs to their friends��� children, for example.

In fact, meritocracy and free markets are incompatible. A free market rewards those who give customers what they what, even if what they want is mediocre or worse: it rewards mindless and clickbait more than quality journalism; X Factor wannabees more than good singers; reality TV stars more than people with ability.

Of course, some of you might try to avoid this dilemma by defining merit as whatever is popular and sells ��� that Katie Hopkins or Joey Essex are more meritorious than doctors or teachers. But this would be simply a moronic misuse of language in an attempt to sidestep a genuine philosophical problem.

And it���s certainly not a ruse that intelligent free-marketeers would use. Hayek was well aware of the fact that meritocracy was inconsistent with free markets:

[The function of the price system] is not so much to reward people for what they have done as to tell them what in their own as well as in general interest they ought to do. ���To hold out a sufficient incentive for those movements which are required to maintain a market order, it will often be necessary that the return to people���s efforts do not correspond to recognizable merit���In a spontaneous order the question of whether or not someone has done the ���right��� thing cannot always be a matter of merit. (Law, Legislation and Liberty vol II, p71-72 in my copy)

In this sense, Ms May���s words represent a sharp break with free market ideology. In fact, this isn���t just true in this sense; free marketeers are also unhappy with her rediscovery of activist industrial policy. If they valued intellectual consistency more than tribalism, I���d expect classical liberals and free market thinktanks to be strong opponents of this government.

This raises the question, though: what is Ms May thinking?

One possibility is that, like people of all parties who claim to be meritocrats, she isn���t thinking much at all and doesn���t realize what meritocracy entails.

But there���s another possibility. Ms May senses that inequalities are undermining the legitimacy of actually-existing capitalism (which is of course very different from a free market economy) and she regards meritocracy ��� or rather a weak pseudo-meritocracy ��� as a means of restoring that legitimacy.

September 8, 2016

When newer isn't better

William Broadway, a student at Loughborough University, has invented a way of keeping vaccines cool which might save over a million lives by reviving an invention of Albert Einstein���s. This reminds us of an important fact ��� that intellectual progress isn���t necessarily linear. Instead, good ideas can be forgotten and bad ones developed, so that science can regress.

For example, the Romans knew how to remove cataracts, knowledge which wasn���t rediscovered until the 20th century; the steam engine was invented in the first century AD, but long forgotten; and the standard of battlefield medicine might well have been higher in the British civil wars than it was at Crimea two centuries later. The renaissance was so-called because forgotten knowledge was rediscovered.

What���s more, a lot of what looks like progress ain���t so. The replications crises in psychology, economics and medicine (if such there be) warn us that new findings aren���t wholly reliable.

I don���t say this to come over all John Gray on you and deny the existence of progress. Instead, I do so to challenge an implicit presumption many of us have - that today���s work is superior to that of 10, 20 or even 100 years ago.

Instead, it���s possible that peer review and grant-awarding processes sometimes select for fashionable rather than effective research; that informational overload means that some good ideas get neglected; and/or that increasingly narrow fields of specialism cause inspiring ideas from separate fields to be ignored.

It���s from this perspective that we should view the debate about the relative merits of stock-flow consistent or heterodox models against DSGE ones. I don���t want to take a view on Brad DeLong���s claim that DSGE models have been ���a catastrophic failure���, but I can say that if they are there���s nothing unique about fashionable research programmes being a dead-end or in once-forgotten ideas proving powerful when they are revived.

To take but two examples of the latter, I���d suggest that the macroeconomics of income distribution are better analysed through Marxian-Kaleckian (pdf) models in which power matters rather than through more ���modern��� theories, and that the theory of natural selection ��� which Darwin took from economics ��� contains many insights that enrich our understanding of economics.

My point here should be a trivial one. We should not presume that newer means better, because institutions don���t always select ideas optimally. One reason why we should study the history of ideas is that doing so reminds us of this fact.

September 7, 2016

Neither Smith nor Corbyn

Back in 1986, someone at L���Uomo Vogue got the idea of doing a fashion shoot at my college, using male students as models. The commissioning editor pitched up one morning, looked at the undergraduates desperately trying to look cool and asked contemptuously: ���is this all there is?��� The spectacle of the Labour leadership election reminds me of that question.

For me, the strongest element of the case against Corbyn is simply that there are so many stories of rank bad management - of, as Sunny says, ���a level of incompetence that is frankly embarrassing.��� It���s not good enough to reply that such stories are exaggerated by Corbyn���s enemies: leadership is performative; if people say you���re a bad leader, you are.

In this context, there���s something worrying about his well-attended rallies: I fear they demonstrate a desire to stick within his comfort zone and preach to the choir, rather than undertake the necessary but harder job of winning over sceptics. This is the worst sort of stupidity ��� a lack of desire to learn.

It���s also in this context that I interpret his longstanding apologism for terrorists and tyrants. What worries me about this isn���t so much that it presages a lousy foreign policy but that it betokens bad judgment ��� thinking that doesn���t extend beyond ���my enemy���s enemy is my friend���.

Many of you would add to this that Corbyn is ���unelectable���. I discount such claims very heavily because we simply cannot predict the future: ���electable��� is often the whine of over-entitled centrists upset that a politician isn���t playing by their rules.

But I don���t discount them entirely, There���s a danger ��� maybe small but non-negligible ��� that a Corbyn victory would lead some to Labour MPs setting up as a separate party. Under the FPTP system, this would reduce the left���s chances of electoral success. The fact that the Corbyn camp are hopeful of avoiding this might tell us less about its probability and more about their overconfidence.

The case against Corbyn thus seems overwhelming.

But it isn���t.

For one thing, I see no evidence from Owen Smith���s behaviour or history that he is personally well-equipped to be leader. In fact, his frequent mis-speaking ��� the implicit homophobia in describing himself as ���normal���, calling Corbyn as a ���lunatic���, wanting negotiations with Isis ��� suggests a lack of judgment. Given that no Labour leader will ever get a fair ride in the media, this weakness matters.

And then there���s policy. The biggest fact here is that it���s not 1997 any more ��� a fact which, as Paul says, some of Corbyn���s critics haven���t grasped. Capitalism has changed radically in the last 20 years. We���ve seen dynamism replaced by stagnation, bond vigilantes by a safe asset shortage, and 90/10 inequality superseded by the rise of the 1%. All this requires a new form of leftist politics. Corbyn knows this. Granted, he might know it only in the way that a stopped clock is right twice a day, but this is good enough.

You might reply that Smith���s policy platform suggests that he grasps it too. I���m not so sure. He might simply be telling party members what they want to hear. There���s a danger that this same triangulation would lead Smith to move rightwards after being elected. This wouldn���t just be a betrayal of Labour members. It would also be a step away from economic literacy and back towards mediamacro and managerialism.

Yes, Smith might do a less bad job of uniting the PLP. But this could come at a cost ��� not just of worse policy but also a weakening of Labour as a mass party as those who have been inspired by Corbyn leave or become disillusioned.

One under-rated danger here is the generational divide. A Smith victory ��� if followed by a rightward retreat ��� would say to those younger people who have been energized by Corbyn: ���politics is not for the likes of you; it���s just a Westminster bubble���. I don���t like the potential longer-term cultural effects of that.

Yes, a Smith leadership might ��� just might ��� see a slight improvement in Labour���s chances of winning a general election. But this comes at a high and dangerous price.

I can���t therefore support either candidate. You might think this is a plea for a more competent version of Corbyn. But it���s not clear that such a person exists. One rational solution to this would be to split the Labour leadership into a more collegiate form. I fear, however, that such a sensible move is precluded by our backward political and intellectual climate.

September 3, 2016

On incompetence

Should ineliminable incompetence play a bigger role in economic and political thinking?

My trigger for asking is a piece in the Times by Oliver Kay on the appalling mismanagement of football clubs such as Blackburn Rovers, Charlton, Leeds and Blackpool. But of course, incompetence is much wider than that. Trains are late and overcrowded; building projects run over time and budget; utilities, banks and broadband providers often have poor quality service that can���t wholly be explained by profit-maximizing; and you all have examples of bad management in your own workplace.

Which brings me to a paradox. Whereas our own eyes tell us that incompetence is ubiquitous, standard economic theory regards it as merely a temporary deviation. It thinks that agents are incentivized to optimize; that badly managed assets will be bought cheaply by people better equipped to run them; and that competition will drive incompetent firms out of business.

But this doesn���t happen ��� at least not fully. Even the best incentives can���t put in what God left out: I have an incentive to become a Premier League footballer or Nobel laureate, but you���d be ill-advised to bet on me becoming either. Credit constraints, among other things, prevent assets flowing to their best managers. And Bloom and Van Reneen have shown (pdf) that, in all countries, there is a ���long tail of badly managed firms���, which tells us that competition doesn���t fully weed out idiots.

The failure here, though, isn���t merely one of Econ 101. Real people make the same mistake.

We know that stock-pickers pay too much for growth (pdf) stocks and ones on the verge (pdf) of collapse. One reason for this might be that they underestimate the ubiquity of incompetence ��� the fact that managers can���t grow firms or turn them around as easily as thought.

And in politics neoliberals overstate the extent to which incompetence can be removed by competition and/or well-paid management whilst the left exaggerates the benefits of nationalization. Not only do we over-estimate state capacity, but we also over-estimate management capacity*. Perhaps we underestimate the extent to which success is a matter of luck and then habit plus marginal gains.

Even the English language misleads us here. Think of the synonyms and near-synonyms for incompetence: mistakes, errors, ineptness, ineffectual, bungling, incapability and so on. All of these suggest a shortfall from a norm of competence. But perhaps the opposite is the case ��� that it is incompetence that is the norm. As Paul Ormerod said (pdf):

Failure is all around us. Failure is pervasive. Failure is everywhere, across time, across place, and across different aspects of life���Yet the existence of failure is one of the great unmentionables.

Here, we ��� or at least we economists ��� perhaps need a paradigm shift. It���s a clich�� that economics has a powerful theory of optimization. But we also have a powerful theory of incompetence. The cognitive biases programme explains how it persists. For example, the planning fallacy predicts that complex projects will over-run budget; the overconfidence effect tells us that assets will sometimes be bought not by those best able to run them but by those who over-estimate their ability to do so, such as the Venkys at Blackburn; Bayesian conservatism predicts that bosses will under-react to feedback; and so on. I might add that the optimism bias causes us to under-rate these mechanisms.

My point here is perhaps an old conservative one ��� that our institutions, public and private, are deeply imperfect and might well remain so, that there is, as Adam Smith said, ���a great deal of ruin in a nation.��� Remembering this might not be good politics: there���s a danger it���ll reinforce the status quo bias. But it would be good for our mental health.

* One thing I found irritating about much of the coverage of the collapse of BHS was the lack of distinction between the failure of the company, which was forgivable and perhaps unavoidable, and the plundering of the pension fund, which was neither.

August 24, 2016

Truthful lies

The tiresome kerfuffle about whether Jeremy Corbyn lied about being unable to get a seat on a train raises a question: so what if he did lie? We all do. Often, a lie can be a way of expressing a bigger truth. Telling your partner that she looks good in that new dress is a lie that expresses the more important truth that you love her. Likewise, Corbyn���s video gets at the truth that trains are often overcrowded and expensive.

The question is: how wide is the domain of truthful lies?

I suspect it���s very wide indeed. One example of course is art. Literature, film and TV are fictions that aim at telling truths. As Stephen King said: ���Fiction is a lie, and good fiction is the truth inside the lie.���

Another example is that lies can embolden us to succeed. The team that believes ���we can do this��� has more chance of winning than one with more realistic beliefs. As Arsene Wenger said, ���If you do not believe you can do it then you have no chance at all.��� The lie of overconfidence might lead to the truth of success.

Another class of examples arises from a variant of the theory of the second-best. We know from welfare economics that, in a sub-optimal world, policies that would otherwise be undesirable can actually increase well-being. For example, where there is a monopoly, price controls might be justifiable. Likewise, in a world where there are barriers to truth, lying might be a justifiable way of shifting us towards the truth.

This might apply in Corbyn���s case. If he had made an honest speech about the shortcomings of our railways it would have been soon forgotten if it had been noticed at al. As it is, his stunt has focused more attention on the issue.

Another case where lying might be acceptable is that it might be easier to pander to people���s beliefs than to confront them head-on. Nick Robinson once told Jonathan Portes that the man who was honest about immigration ���would not have a chance of getting elected in a single constituency in the country���. It might be better for pro-immigration candidates to lie and then enact reasonable policies and show that these have worked than to try to change voters��� beliefs beforehand. As the old saying goes, it���s easier to ask forgiveness than permission. Whether this strategy works is a matter of tactics, not morality.

Lying is, therefore, often acceptable and, as Sir Malcolm Bruce said, it is common in politics. So, when is it wrong? There are several occasions.

One is the simple prudential one ��� that you might not get away with it. Corbyn���s critics claim that ���traingate��� has been deflected onto the question of his honesty. The objection here is not that he was morally wrong to lie, but that he was an incompetent liar. Here, the left is fighting an uphill battle; its lies will be more quickly exposed by the media than those of the right.

Also, of course, what matter is the cause the lie serves. Lying to a murderer is acceptable; lying to the policeman chasing him is not. What was wrong about Brexiteers��� lies is that they served a bad cause. It���s for this reason that children can get confused: we teach them to tell the truth, but to lie when great-aunt Jemima asks if they like her new hat.

A third problem is that you can easily get high on your supply. I suspect many decent Labour candidates lied about immigration and fiscal policy at the last election. My fear was that they would come to believe the lies. A similar thing might have happened to Brexiteers: their lie that negotiating Brexit would be a doddle led them to being woefully under-prepared for the slog of doing so.

You might add that there���s a further objection to lying ��� that it debases the quality of political debate. A bit of me sympathizes. But another bit makes me think this ship sailed long ago. Politics is about power, not truth. Expecting politicians to tell the truth all the time is a childishly na��ve Kantianism, rather like expecting to win a war without firing a shot.

August 23, 2016

Bonuses: here to stay

Neil Woodford���s decision to scrap bonuses at his fund management firm poses the question: does this mean big bonuses in the finance industry are on the way out? I don���t think it does.

First, though, a word of praise. Mr Woodford���s colleague Craig Newman is right to say:

There is little correlation between bonus and performance and this is backed by widespread academic evidence.

One reason for this is that badly-designed incentives can incentivize the wrong behaviour, such as short-termism, cooking the books or chasing risk. A further reason is that bonuses can crowd (pdf) out intrinsic motivations (pdf), the desire to do a good job for the sake of it.

However, the financial industry doesn���t pay bonuses because they are good incentives. They weren���t introduced because bosses saw their staff slacking off and decided to incentivize them. Instead, bonuses are a legacy from an old business model.

Consider the old-style merchant banks and stockbrokers ��� the sort of firm I joined from university. Because these depended upon takeover activity and stock market conditions, they had volatile revenues. Bonuses were the solution to this: the reduced the need to lay off staff during downturns. They were an example of the ���share economy��� advocated by Martin Weitzman and James Meade; the rich have always liked socialism for themselves.

What they were not were incentives. Staff didn���t much need to be incentivized simply because they were directly overseen by the businesses' owners, the partners ��� and some of them were pretty scary.

In this context, it���s easy to see why Mr Woodford is scrapping bonuses. His business - for now anyway - has relatively stable revenues so there���s less need to stabilize profits through revenue-sharing. And he only employs 35 people, so he can oversee them directly. I���d add that a big part of his business ��� his equity income fund ��� is largely a play upon the longstanding defensive anomaly (pdf), and you don���t need high-powered incentives to do that.

However, whilst his decision is a good one for his business, it might not be applicable to other companies, where revenues are more volatile and direct oversight not possible because of bigger staff numbers.

I���d add three other possible reasons why bonuses might continue:

- Although they might not incentivize good behaviour, there are circumstances in which they might deter (pdf) bad. The prospect of a big bonus deters traders from selling assets cheaply to a rival firm which they later join.

- There���s an element of mispricing in relative salaries in finance: you can end up hiring a duffer for ��500,000 or a star for ��100,000. Bonuses in the first year allow such mispricings to be corrected; paying a recent hire a bonus is a way of compensating him for having a relatively low initial salary.

- It would be a brave large bank that scrapped bonuses in the hope of crowding in intrinsic motivations. Some people enter banking precisely because they are motivated only by cash ��� maybe not many, but enough to do damage. They���d get the hump if bonuses were scrapped. The status quo bias is a powerful force, and often rightly so.

I suspect, therefore, that bonuses in some form will remain a big part of finance.

August 22, 2016

Capitalism, neoliberalism & excellence

The Olympic games have raised an old question: does capitalism encourage the pursuit of excellence or does it stifle it?

The question matters because any good social structure should facilitate both virtue and freedom. It should allow us to be the best we can be, whilst freeing us to pursue our own goals, whether these be artistic or sporting excellence or mere mediocrity.

Marx���s gripe with capitalism ��� perhaps his biggest gripe ��� was that it failed on this score. He thought work should be a means of human development but that under capitalism it became an alienating, tyrannical force, in which the pursuit of money drove out self-actualization*.

Was he right? There are some reasons to think not.

One is simply that capitalism has delivered the material prosperity that enables us to pursue our individual goals whereas pre-capitalism condemned us to what Marx called rural idiocy. The high-tech bikes and equipment that drove British cyclists to gold were creations of capitalism. And capitalist growth has been an enabling force for thousands. For example it has made musical instruments more affordable ���John Lennon���s first guitar cost ��5���10��� in 1956, which was half a week���s wages ��� and the internet means that great music is freely available and that musicians can find some sort of audience.

Also, there���s no necessary conflict between the goals of excellence and mere money-grubbing. Tin Pan Alley and the old Hollywood studio system both chased the dollar, yet they gave us great art too. John Kay has described how some companies became big and profitable by making great products rather than being focused on shareholder value. And Deirdre McCloskey has shown how capitalism rewarded and thus cultivated virtues such as trustworthiness and prudence.

But on the other hand, Marx���s claim is surely still true for millions. Work is still a form of drudgery dedicated to earning a living rather than to higher ideals. When Jeremy Corbyn said ���there is a poet, a painting, a novel, a play in all of us��� he meant that capitalism stifled our creativity. As Alasdair MacIntyre said in After Virtue, only a few of us can get paid for pursuing excellence. Capitalism, therefore, he thought, marginalizes the goods of excellence.

It is, therefore, moot whether capitalism promotes excellence or not. Our Olympians exemplify this ambiguity. On the one hand, many are supported by lottery funding because capitalist markets do not reward their urge to master niche sports: unless they get lots of advertising endorsements, most of them, I suspect, will earn less than Joey Essex. But on the other hand, capitalism has generated an affluence that permits the luxury of helping some people chase their dreams**.

More prosaically, my own career reflects this ambiguity. If I were to try to maximize my earnings, I���d probably have done an even worse job at the IC than I have. I would have promoted rip-off actively-managed funds in the hope of getting a PR job in fund management. Or I���d have written bog-standard macro stuff that flatters my readers��� prejudices and so been employable on a national newspaper. However, I can only afford to resist these pressures for lower standards because early in my ���career��� I accidentally made enough money not to have to debase myself now.

So, for me it is unclear how far capitalism facilitates the pursuit of excellence.

We must, however, distinguish between capitalism and neoliberalism. One of the examples John Kay gives of how excellence can be profitable was ICI. When it was a chemicals company, it became great. But when it tried to maximize profits, it soon failed. The old ICI was a capitalist firm. The later ICI was a neoliberal one.

The point perhaps generalizes. Capitalism gave us Citizen Kane and Ella Fitzgerald. But neoliberalism gives us Simon Cowell and mindless sequels.

Free markets might well provide some space for the pursuit of different ends and of excellence ��� especially if accompanied by some judicious state interventions. But neoliberalism, in the sense of chasing money and (managerialist) power is more totalitarian. For this reason, among others, we should distinguish between the two.

* Here���s a brief explanation of alienation by Gillian Anderson. I���m in love.

** Or has it? The old USSR also produced many great athletes, albeit perhaps through less than laudable methods. Perhaps any system that produces a surplus facilitates excellence.

August 21, 2016

Cognitive biases for Corbyn

I���ve long said that support for capitalism and tolerance of inequality is founded in part upon cognitive biases. But I wonder: could it be that support for Corbyn is also based in part upon such biases?

I���m thinking of at least four different ones.

One is wishful thinking. Paul Mason says these are ���days of hope��� for the left because ���neoliberal capitalism is busted, discredited and on life support.��� I agree that neoliberalism is discredited. But so what? Politics is about power not intellectual validity, and bad ideas can remain dominant for a long time. What���s more, the backlash against neoliberalism seems to be taking the form not (just) of leftism but of the sort of reactionary anti-immigrant sentiments that gave us Brexit.

Granted, Paul is right to take heart from the fact that ���people are flooding into a left-led Labour party���. But how important this proves to be rests upon network effects which seem to me to be uncertain. If the new members help to persuade floating voters to support Labour ��� either through conventional leafleting and canvassing or simply though day-to-day conversations in pubs and workplaces ��� then there are grounds for hope. But if they are just a circle-jerk of clicktivists there aren���t. Corbyn���s awful poll ratings aren���t yet sufficient to adjudicate this issue, because the process of day-to-day conversations will take a long time to work, if it does at all.

Secondly, there���s a false consensus effect. It���s easy to look around one���s circle of like-minded friends, and at the hundreds of people at Corbyn���s rallies, and infer that one is part of a mass movement. Of course, opinion polls controvert this belief, but as David Hume famously said the impressions formed by our own experience are more forceful and vivid that mere ideas and second-hand reports.

Thirdly, there���s the confirmation bias, or a form of post-purchase rationalization. Having backed Corbyn, there���s a tendency to interpret ambiguous evidence as supportive of one���s decision. So, for example, his supporters put great weight upon his achievements ��� shifting the party leftwards and building a mass membership ��� and downgrade the many stories of his personal incompetence as leader.

Fourthly, there���s the poisoning the well fallacy. Yes, many of Corbyn���s enemies are careerists, Quislings and idea-free triangulators (it would be unfair to call them technocrats as they have no technique). But this does not mean that all their complaints about him are wrong. To discredit all these complaints because they come from ���Blairites��� or ���red Tories��� is to commit the fallacy of poisoning the well.

The combination of the confirmation bias and poisoning the well fallacy generate asymmetric Bayesianism ��� a tendency to overweight evidence for one���s prior belief and downgrade contrary evidence.

Now, I���m aware that in saying all this I risk being accused of seeing cognitive biases everywhere. As the old jokes go, we���re all guilty of the false consensus effect, and since I learned about the confirmation bias I���ve seen it all the time. Nevertheless, it would surely be a remarkable accident if errors of judgment were found only on the right. It seems to me that, in some cases, the passionate support which Corbyn attracts is disproportionate to the evidence of his merits ��� evidence which, I stress, isn���t wholly absent.

There is, though, a problem here, of which rightists remind me every time I claim that capitalism is sustained by cognitive biases. It���s that we can sometimes reach the right conclusion via flawed reasoning: just because you���re irrational doesn���t mean you���re wrong. Is this the case with Corbyn? I confess to be being unsure.

August 19, 2016

On arms races

There���s a nice headline in the Times today:

Make us sell healthy food, supermarkets implore May.

This invites the obvious reply: if you want to sell healthy food, why don���t you just do so?

The answer lies in competitive pressures. If any individual supermarket tries to cut salt in its products or refrains from special offers on unhealthy foods, it would lose market share to rivals.

Each individual supermarket���s rational attempts to maximize profits thus leads to an outcome which none of them really wants ��� the over-marketing of unhealthy food. This is an example of an arms race, a process whereby individually rational behaviour has results which are collectively undesirable. Here are some other examples:

- If all companies try to pay above-average wages to attract the best CEO, the result is no better quality of management but ever-rising salaries. The same thing is true for football transfer fees.

- If everybody works long hours in the hope of promotion nobody���s chances improve, but everybody ends up working (pdf) longer than they���d like.

- If everyone buys a flash car to impress the neighbours, nobody���s impressed but everyone���s in more debt.

Such processes are well described in, for example, Robert Frank���s Darwin Economy and Tom Slee���s No One Makes You Shop At Wal-Mart.

Arms races are a counter-example to free marketeers��� claims that, via the invisible hand, individual choices within a free market lead to optimal behaviour. This isn���t to say that such claims are wrong; they are often right. Instead it���s just to corroborate Jon Elster���s point that in the social sciences there are no (or very few) iron laws but rather different mechanisms that work or not depending upon particular contexts.

When there are arms races, it���s reasonable for the parties to make the appeal that supermarkets are making: ���save me from myself.���

This, of course, should be the essence of politics. Politics is ��� or should be ��� the art of solving problems of collective action. If individually rational actions always led to outcomes which were optimal in aggregate there wouldn���t be a role for the state.

However, one feature of David Cameron���s governments was that they didn't see this. The most egregious example of this was of course the failure to see that attempts to pay off ���the nation���s credit card��� would fail because of the paradox of thrift. But there were others, such as encouraging panic-buying of petrol during the threatened lorry-drivers strike of 2012, or demanding that shareholders take more control of companies without seeing the obvious free-rider problem in doing so.

From this perspective, the ���damp squib��� of the government���s obesity strategy suggests that Ms May is continuing to make the same mistake as her predecessor.

August 18, 2016

On job polarization

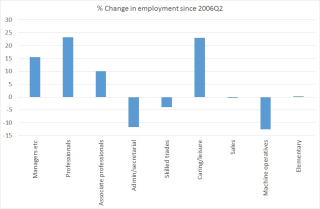

Job polarization is a big problem. This is one message I take from figures released yesterday by the ONS showing employment by occupation.

These show that in the last ten years we���ve seen big rises in ���professional occupations��� and in managers, directors and senior officials ��� up by 23.3% and 15.5% respectively. But we���ve seen falls in secretarial and skilled jobs. And within the ���unskilled��� occupations, there���s been a shift from machine workers to care workers; this is partly due to the 3.5% drop in manufacturing output during this period.

These numbers exclude the self-employed, and don���t tell us anything about the nature of the employment contracts: some of the rise in caring jobs, I suspect, is in the form of precarious zero-hours contracts.

There���s little sign of these trends ending. In the last 12 months, managerial and professional jobs have increased by 5.7% and 4.8% respectively whilst secretarial and skilled jobs have fallen.

This matters, I reckon, for at least six reasons:

- It helps explain why the graduate premium has been stable recently, despite rising numbers of graduates. It���s because, as the IFS says, firms have created more graduate jobs. This increased demand for graduates is evident in relative wages: in the last ten years managers��� wages have risen by 37.2%, twice the rate for secretarial or care workers.

- It suggests that social mobility will be low. The clich�� of a man rising from the post-room to the boardroom will become even rarer, not just because there are no longer any post-rooms but because the middling jobs a post-boy could have risen to are also declining. It���s hard to climb a ladder when the rungs are missing.

- It suggests that, in the absence of offsetting policies, we might see increases in household inequality simply because of increased assortative mating (pdf). In the 50s and 60s, inequality was mitigated by professional men marrying their secretaries. Now, they marry their fellow managers and lawyers.

- It poses questions about the feasibility of vocational education. Where will be the good jobs in the future for people who aren���t academically inclined? This question is, of course, sharpened further by the possibility that technical change will destroy lots of jobs.

- It deepens the productivity puzzle. We might expect rising numbers of managers and professionals to be accompanied by rising aggregate productivity, if only as a compositional effect: managers and professionals have higher wages and so (in neoclassical theory!) are more productive. That this hasn���t happened makes it even stranger that productivity has stagnated.

- It has contributed to social polarization. The EU referendum highlighted a divide between optimistic graduates and less educated people who are pessimists: the Ashcroft poll showed that a majority of leave voters believe that life will be worse for children than it was for their parents. This is consistent with the fact that falls in secretarial and skilled jobs show that there are fewer good jobs for on-graduates. Our socio-political divide has an economic base.

In these ways, job polarization isn���t just an economic curiosity. It���s a profound political problem ��� one that might not be cured merely by further expanding the number of graduates. If we had a serious political class, this issue would be high on the agenda. But we don���t, so it won���t be.

Chris Dillow's Blog

- Chris Dillow's profile

- 2 followers