Chris Dillow's Blog, page 72

October 21, 2016

The freedom-hating right

The Sun wants the BBC to sack Gary Lineker for ���peddling lies.��� Let���s leave aside the fact that the Sun is much better at peddling lies that Mr Lineker ever will be. What this shows, yet again, is that the right is now the enemy of freedom.

We should put this demand alongside the Mail and Express���s calls for pro-Remain ���traitors��� to be silenced; the Tory attacks upon independent institutions such as the Bank of England; the investigatory powers bill; and the fact that many supporters of immigration controls also want (pdf) controls over other areas of economic life. And, let���s remember, immigration controls themselves are attacks upon freedom: they deprive people of the freedom to live where they choose or hire whom they choose.

All these are examples of the right���s hostility to freedom. Yes, this hostility might be popular ��� but that tells us only that there can be a tension between liberty and the will of the people.

To those of us of a certain age, this illiberal trend might look odd. During the 60s and 70s the clich�� was that there was a trade-off between equality and freedom and that the left leant towards the former whilst the right favoured the latter. And western Cold Warriors were forever proclaiming the virtues of freedom against the ���evil Empire��� that was the USSR.

So, what happened?

In truth, not much. In many cases, the right���s espousal of freedom was only ever a pretence. Whilst they pretended to bemoan the USSR���s lack of freedom, they supported Pinochet, apartheid and the repression of women and gays, and were (and are) untroubled by coercion in the workplace. The only freedom the right truly believed in was freedom for bigots and exploiters.

I say all this because many people still don���t seem to realize it ��� perhaps because their instincts were formed during the Cold War. There���s an odd type of lefty or ex-lefty who whines about no-platforming and restrictions on free speech at universities whilst under-appreciating the fact that the biggest threats to liberty don���t come from silly teenagers. And many of those who think of themselves as supporters of freedom (such as the Adam Smith Institute?) seem to associate more with rightists than lefties.

I���ve said it before, and I���ll say it again. It is we Marxists, more so than rightists or centrists, who are the champions of freedom. What we���re seeing now is yet more vindication of this.

Another thing: bigots please note. Paying your TV licence does not give you a right of veto over every BBC appointment.

October 20, 2016

The upside of relative decline

���Being in politics is like being a football coach. You have to be smart enough to understand the game, and dumb enough to think it's important.��� This piece by Simon Head on the decline of British business reminds me of these words by Eugene McCarthy.

Simon is, of course, reviving an old theme. Back in the 70s, we were obsessed with Britain���s relative economic decline ��� a decline summed up by the engineering boss who said: ���I don���t understand why we���ve lost so much market share in the last 30 years. I mean, we���re making exactly the same products.���

There were several reasons for that decline which are still present: short-termism, a lack of good vocational training, poor employee engagement and bad management; for example Bloom and Van Reenen show (pdf) that British manufacturing bosses are on average worse than those in some other advanced nations. We might add that the US���s big home market gives it an advantage in businesses that benefit from Metcalfe���s law such as Google, Facebook and Twitter ��� but this can���t explain why the UK also does relatively badly in businesses faced with diseconomies of scale.

I want to suggest something else. It lies in McCarthy���s line. Successful bosses are like football coaches: they must be smart enough to understand the game but dumb enough to think it matters. Britain has a relative dearth of such people.

It used to be said that one cause of the UK���s relative decline was that our industrialists cleaved to an ideal of being a country gentleman; they aspired to become leisured aristocrats rather than tycoons. Here���s Martin Wiener (though Perry Anderson, Tom Nairn and EP Thompson said similar things):

The consolidation of a ���gentrified��� bourgeois culture, particularly the rooting of pseudoaristocratic attitudes and values in upper-middle-class educated opinion, shaped an unfavourable context for economic endeavour���Industrialists themselves���gravitated towards what they saw as aristocratic values and styles of life to the detriment, more often than not, of their economic effectiveness (English Culture and the Decline of the Industrial Spirit, p10)

I suspect there���s still a lot in this. Very many of my rough contemporaries jump off the gravy train or get out of the rat race (I mix my metaphors merely to note their pejorativeness). Alienated by corporate imbecilities or the grunt-work of bureaucracy they downshift to comfier jobs, a couple of non-executive directorships or a hobby business. Those of us who are upwardly mobile and so don���t fit into the corporate upper-class are perhaps especially likely to do this.

Most of the people who are smart enough to understand business are also smart enough to get out of it. The tycoon mentality ��� the desire to keep making millions you can���t spend ��� is lacking.

Arsene Wenger says of Mesut Ozil and Alexis Sanchez that ���they can raise a little bit above the financial aspect of the game because they are not poor and they have to look really on the football side.��� He���s hinting at an important fact ��� that successful people are usually not motivated by money; the idea of ���greedy bosses and bankers��� is lazy leftist moralizing. Instead, they have internal, not extrinsic motivations. Often, though, these mitigate against building huge businesses: the man who loves solving engineering puzzles and inventing new products often won���t enjoy the very different challenge of expanding production and sales. So he might well sell up when the business is still small. It���s easier to find intrinsic satisfaction in being an engineer or coder or even trader than it is in being a manager.

In saying this, you might think I���m lamenting decline. Not entirely. Just ask: what does motivate a man to want to keep working once he���s made a few million? In some cases, the answer is: vanity: many very rich businessmen have monstrous egos. Perhaps, then, there���s an upside to the UK���s relative lack of successful businessmen. Sure, we have no Steve Jobs or Larry Ellison. But we also have no Donald Trump or Silvio Berlusconi.

October 19, 2016

In defence of Bank independence

The Tories seem to be undermining the Bank of England���s independence. First, Theresa May says there ���have been some bad side effects��� of low interest rates: ���people with assets have got richer���people with savings have found themselves poorer. A change has got to come.��� Then Lord Hague says that low rates are ���penalising the poor and the prudent" and ���losing credibility and producing very dangerous side effects.��� And then when Mark Carney queries this, David Davies tweets:

Mr Carney you are an unelected bank official. Theresa May has got every right to tell you how to do your job!

I���m unhappy with these developments. For one thing, as they stand they are plain wrong in three ways:

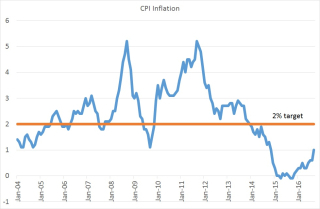

- Since 2014, inflation has been below its target. This means that if the Bank has erred, it has been by having too tight a policy. Interest rates have been too high, not too low. Savers haven���t been penalized enough.

- If Ms May wants the Bank to raise real interest rates, she has the means to do so. She could reduce the inflation target, and remove the Bank���s ability to ���look through��� short-term price increases.

- Any successful stimulatory monetary policy will cause people with assets to get richer. This is simply because it will raise expected future GDP and hence raise share prices.

But my disquiet goes further than this.

One problem I have is that none of these statements address the logic for central bank independence. This is that, because central banks have no incentive to stoke up pre-election booms, people will trust them to deliver low inflation. This reduces inflation expectations, which helps reduce inflation at no cost in terms of output. The empirical record is consistent with this theory: see, for example, this paper (pdf) by Athanasios Anastasiou and the many papers he cites.

This is not to say there���s no case against Bank independence. You might argue that it entrenches anti-austerity ideology by reinforcing the notion that aggregate demand must be suppressed. And it���s sometimes said (pdf) that it might cause a lack of coordination with fiscal policy. Personally, I don���t find these arguments convincing. Shifting control over rates back to the Treasury won���t in itself overturn anti-austerity ideology. And in recent years the obstacle to fiscal-monetary coordination has been the zero bound rather than Bank independence. But this debate doesn���t matter: the Tories aren���t arguing along these lines.

Of course, the Bank has made policy errors. But these are inevitable, simply because the economy is unforecastable. There���s no reason whatsoever to suppose that the Treasury would avoid such errors. In fact, pre-1997 history suggests it has been at least as error-prone as the independent Bank.

These attempts to undermine Bank independence are therefore without merit.

I fear, though, that what���s going on here isn���t a narrow matter of macroeconomic management. There might be more to it. The idea that the government knows better how to set interest rates is part of a pattern. It���s part of the same mindset that thinks the government has the capacity to negotiate good trade deals, or the ability to enforce sensible immigration controls.

This is the same mindset behind the Brexit slogan, ���take back control��� - the urge that government must be in control. From this perspective, an independent central bank is much the same as European judges ��� an unwanted constraint upon government power. When Ms May spoke of a desire to have ���our judges sitting not in Luxembourg but in courts across the land���, I doubt she was calling for a strong independent judiciary.

The kindest thing one can say about this is that it over-estimates state capacity. But it might be more sinister. If we read these attacks upon independent institutions alongside demands to silence ���unpatriotic��� Remainers, what we���re seeing is a step away from liberty and towards totalitarianism.

October 18, 2016

Sterling's effects

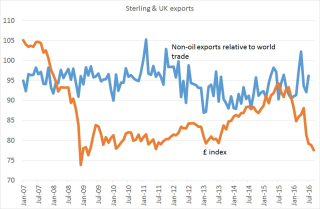

Angus Armstrong has a good piece on sterling���s fall. I just want to add one point, which my chart makes.

It plots sterling���s trade-weighted index against UK non-oil exports relative to world trade volumes.

If a fall in the pound leads to a significant rise in exports, you���d expect to see the blue line rise after sterling���s fall in 2008-09. But it���s hard to discern any such significant move. Certainly, there doesn���t seem to have been any major long-lasting effect. As the ONS wrote (pdf) in 2013, the depreciation of 2008-09 ���appears to have had little impact on the overall balance of trade.���

There are good reasons for this. One is pricing to market. Sterling���s fall has not raised the price of marmite: instead, Tesco and Unilever have absorbed the effect of higher import costs on their profit margins. What���s true of them is true of many other businesses: UK exporters will use sterling���s rise to increase profit margins, not just cut prices for foreign customers.

This is good news in one respect: it will mitigate the impact of sterling���s fall upon inflation. But if prices in the shops don���t change much, nor will demand.

But this isn���t the whole story. Even to the extent that prices do change, trade volumes don���t change much. The OBR estimates that a one per cent fall in relative export prices raises non-oil export goods volumes by only 0.41% after nine quarters, whilst a 1% rise in relative import prices cuts import volumes by only 0.2% (pages 32-37 of this pdf).

There are several reasons for this. One is simply that demand for tradeable goods isn���t very price-elastic, perhaps in part because monopolistic competition means that UK exports aren���t close substitutes for overseas goods. Even if sterling���s fall does lead to (say) Glaxo cutting the foreign currency prices of its drugs, they won���t sell very many more; Germans aren���t going to get more cancer because sterling has fallen.

Another is that the decision to export is an investment decision; firms must invest time and money in sales and marketing. And the same fall in sterling that appears to make exporting profitable also throws sand into the wheels of this mechanism.

Back in 2009, firms didn���t increase their exports much in response to the lower pound because the same financial crisis that depressed the pound also made firms worry that the bank loans they needed in order to increase exports wouldn���t be available. Likewise, uncertainty about future trading rules today might inhibit firms from investing in export marketing.

We can put all this another way. The current account balance ��� which is massively correlated with the trade balance ��� is, by definition, equal to the gap between savings and investment. This tells us that a weaker exchange rate can only reduce the current account deficit if it either increases savings or reduces investment. There is a mechanism whereby this can happen. Historically, rises in inflation ��� of the sort that (slightly) follows a fall in sterling have caused rises in the savings ratio. But this isn���t a very strong mechanism.

In a sense, the very fact that sterling has fallen so much is consistent with what I���m saying. As Paul Krugman said back in 1989 in a book that strongly influenced my thinking on these matters, ���exchange rates can move so much precisely because they seem to matter so little.���

This isn���t to deny any beneficial effect of sterling���s fall. In the social sciences, the question is often not ���is this true?��� but rather ���how true is it?��� And the idea that sterling���s fall will give a big boost to the economy isn���t very true. Yes, sterling is a shock absorber ��� but it���s not a very powerful one.

In this respect, Brexiters who claim to the contrary are at least consistent. One feature of rightist thinking is elasticity optimism. The belief that minimum wages destroy lots of jobs, or that tax cuts have big effects upon labour supply are both examples of this. And the idea that sterling���s fall will be a very good thing is another. Sadly, though, there are good reasons to doubt it.

October 16, 2016

On being a little Englander

Nick Cohen says the far left is gripped by anti-western illiberalism and the Home Affairs select committee accuses it of anti-Semitism. Do these accusations apply to me? I don���t think so ��� but not for reasons that reflect any credit on me.

I have never expressed support for Putin or Hezbollah for the simple reason that I take minimal interest in foreign affairs.

This is because I just don���t have the cognitive bandwidth. In complex societies ground truth matters. And it would take vast amounts of time for me to get even the weakest grasp of this ��� a knowledge of Arabic being a minimal requirement. I know from economics that media reports are often inadequate and biased: why should I believe things are much different in foreign affairs? And accounts from partisans are equally (more so?) unreliable: whenever I have the misfortune to accidentally hear from someone in the Israeli-Palestine conflict they often strike me as raving lunatics ��� more so than those who disagree with me on most domestic issues.

You might object here that there are some issues that are clear-cut, such the massacre of civilians in Aleppo or Putin���s repression of free speech. True. But there���s a massive gulf between an obvious problem and the solution. The world isn���t divided neatly between goodies and baddies, and interventions can make things worse.

It seems to me personally, therefore, that in the face of complexity and the high costs of acquiring reliable information, there���s something to be said for rational ignorance. The cost of moving even from being uninformed to badly informed is high.

I suppose I could speak out against obvious human rights abuses, but this would be mere virtue signalling. I���d rather spend my limited time and mental faculties on other matters. And I suspect it���s better for everyone if I do: the world is more fully stocked with self-righteous blowhards than it is with people who have half a clue about some economics. Insofar as I can make a difference - which I doubt - it is by developing my faculties as the latter.

Now, at this stage you���ll have two objections.

One is that I���m a hypocrite. I did support anti-apartheid causes in the 80s, so why should I now claim ignorance of overseas affairs?

I���d contend that that was an exception. Apartheid was such a great evil that it seemed that pretty much anything was superior to it. Subsequent events support this: although South Africa suffers corruption, crime and high unemployment, pretty much nobody would prefer apartheid.

There���s another objection. You might claim that the view I���m expressing is smug, insular and self-satisfied Little Englanderism.

And you���d be right.

However, the only way I could avoid both this objection and Nick���s would be by becoming a liberal polymath. But even if I had the intellectual faculties and inclination to do so, I���d lack the time: I have to earn a living. As Adam Smith said, the division of labour makes a man ���as stupid and ignorant as it is possible for a human creature to become.���

October 15, 2016

Reclaiming the N-word

The Adam Smith Institute is rebranding itself as ���neoliberal���. I'm not sure this is a good idea.

I say this not because I disagree with them ��� though I do on some matters ��� but because of the respects in which I agree with them.

I agree that capitalism has been a force for progress ��� as, of course, did Marx. I agree that hard-core libertarianism is a difficult position to sustain; it always required a very selective reading to suggest that Adam Smith was a libertarian. And I agree on the need for some kind of mixed economy.

However, there are (very roughly speaking!) two types of mixed economy.

In healthy versions, the government corrects market failures whilst the market corrects government failures, and government acts to support entrepreneurship, perhaps in more ways than merely providing stable property rights ��� for example by ensuring the availability of finance and funding or even conducting fundamental research.

In unhealthy versions, however, we have crony capitalism in which the state supports capitalists at the expense of workers and funnels cash towards favoured clients.

And here���s the problem. For many of us, neoliberalism ��� insofar as it means anything ��� is the ideology which helps sustain the latter. Many on the left use ���neoliberalism��� to describe not just free market economics but also managerialism, hostility to the working class, the crass pursuit of wealth and power and the use of the state to enrich capitalists for example via the too big to fail subsidy to banks.

Now, Sam intends to re-appropriate ���neoliberalism��� in much the same way as gays have reclaimed that fine word, ���queer���. But I���m not sure this is wise. There���s a big difference here. Those who used the word ���queer��� to attack gays deserved to be slapped down. But many of those who use ���neoliberal��� as a boo-word are potential allies of Sam.

Here���s what I mean. Both Sam and much of the left favour a liberal approach to immigration, and both would deplore an industrial strategy that favours big business over small. In both respects the left and the Adam Smith Institute can make common cause against Tory statism ��� though of course they differ in other respects! The use of the word ���neoliberal��� would jeopardize this alliance; it could be seen as an attempt to troll the left, and would exacerbate the mindless tribalism that disfigures politics.

So, how should the Adam Smith Institute describe itself? The problem here, of course, is that simple words cannot describe a complex reality. Perhaps an improvement would be simply to say they are advocates of an open society. And we need these.

October 14, 2016

Capitalism & loneliness

The opposite of a great truth is another great truth. I was reminded of this, well, great truth by George Monbiot���s claim that modern capitalism is creating loneliness. This is partly true.

The geographical mobility required by labour market ���flexibility��� can break up families and cause children to move away from their parents. The rare cases of upward social mobility cause us to lose touch with family and friends whilst feeling out of place in our new environment. And the pursuit of external goods such as money and power can generate zero-sum conflicts and fragile identities whereas the pursuit of internal goods, such as mastery of a craft do not; Richard Sennett���s The Corrosion of Character is good on this.

But, but, but. On the other hand, there are ways in which capitalism has ameliorated loneliness.

To see one, try an experiment tonight if you are on your own. Turn off the TV, radio, phone, recorded music and your computers. See how you feel. I suspect you would suffer deeply from boredom and loneliness. You might take solace in a book ��� but remember that before the mass literacy of the 20th century, few could do this. This reminds us that capitalism has provided the technologies for either overcoming loneliness or at least displacing it.

It���s not just the more recent technologies that have done this. One reason why the second industrial revolution transformed lives was that the bicycle and radio expanded people���s contacts.

But capitalism has done something else. It has caused urbanization and so rescued people from what Marx called the ���idiocy of rural life���. By this he didn���t mean that peasants were stupid, but that they were isolated. Before urbanization, your world was pretty much your village ��� in fact the Russian language has the same word for both, mir. And if you���d upset your neighbours or were a bit eccentric, you���d be condemned to almost unendurable solitude.

All this is not mere conjecture. We have empirical evidence. Country music is chockful of references to loneliness; for me, the most harrowing expression of this is Porter Wagoner���s Albert Erving. This suggests that loneliness was a massive problem in the pre-urban and, by extension, pre-capitalist era.

I say all this to raise two points.

Point one is that there might be (yet another!) fundamental trade-off here. The process of creative destruction contains a trade-off for loneliness. One the one hand, the new technologies it gives us can bring people together: we all have friends whom we wouldn���t have met but for the internet. But on the other hand, it means jobs can be destroyed thus weakening friendships and communities. It���s entirely legitimate to ask, as George does, whether this trade-off can be better managed ��� or, indeed, whether we have by now enjoyed all the feasible upsides of the process but still face the costs.

Point two is that music is not simply one note after another. Proper music ��� rather than mindless corporate shilling - gives a voice to the voiceless and a glimpse into perspectives that would otherwise be lost. From this point of view, whatever one thinks about Bob Dylan���s personal merit, the Nobel committee���s decision to award the literature prize to a songwriter was quite justified.

October 13, 2016

Economics as literature

Avner Offer says economics is ���more like literature than like physics���. This might be seen as high-class trolling. Physics contains sums which are hard and scientific and manly, whereas literature is girly and so obviously inferior. For this reason, some economists have long had physics envy, writing papers whose titles offer ���exact solutions��� and ���robust optimization���.

Such a reaction is wrong. Offer is right in ways that reflect both credit and discredit upon economics.

Let���s deal with the discredit first. Economists��� attempts to emulate physics have at least sometimes failed. Romer���s critique of ���mathiness��� and McCloskey���s accusation of scientism have some force. There���s nothing necessarily scientific about long lines of equations: Ronald Coase���s two (pdf) great papers (pdf), for example, gave fantastic insights without any.

What���s more, economics is more like literature than physics in that it doesn���t always progress. We can read 19th century novels with profit, but few physicists would advise their students to study 19th century work on the subject. Likewise, we should read the classical economists, not least because they were interested in issues with much of later economics overlooked, such as the distribution of income between capital and labour.

And some economics is like literature in a bad way. Those RBC models that assume continuous labour market clearing are like Iain M. Banks��� culture novels: they describe societies which do not exist, have not existed and will not exist in our lifetimes. And a common criticism of at least early versions of DSGE models was that they were as scrupulous in ignoring important matters as Jane Austen was in ignoring the source of her gentlemen���s incomes: Charles Goodhart said of the DSGE approach that ���it excludes everything I am interested in.���

Nevertheless, there are two ways in which economics is and should be like literature.

One is that it asks the same question as writers do of their characters: given his motives, information set and constraints, how does he act and with what effects? Sloppy writers and economists give simplistic and implausible answers ��� as in the ���incentives-magic!!-nice effects��� approach of simple-minded free market economics. Great writers and economists, however, are much more careful and insightful. You can think of the recent Nobel prizes given to Hart, Bengstrom and Tirole as rewards for such carefulness.

Secondly, economics must be unlike physics because there are, as Jon Elster said, no (or few) law-like generalizations in the social sciences. Instead, like literature, there can only be detailed studies of time and place ��� although the best such studies yield great insights.

Does this mean that economics isn���t a ���science���? I side with McCloskey. It���s a stupid question. What matters is whether the study is careful and disciplined? The objection to ���mathy��� economics is that it doesn���t bother with the discipline imposed by pesky facts.

In this sense, economics is like literature in that in both there is a constrained subjectivity. Literary scholars might reasonably differ on whether, say, Virginia Woolf was a better writer than D.H Lawrence but most would agree that both are better than, say, Louise Bagshawe. Likewise, whilst there might be disagreement in economics, there can also be unity or at least general consensus about what constitutes rank bad economics.

October 12, 2016

The association fallacy

���We didn���t mean that kind of Brexit��� say Daniel Hannan and Andrew Lilico in response to May���s anti-immigrant proposals. To which we Remainers reply: if you ride a tiger, you shouldn���t be surprised when it bites you. As I wrote before the referendum:

some of you have a vision of a Britain outside the EU that is a free, liberal socialistic country. These are ideals with which I have sympathy. But we are kidding ourselves if we think a vote for Leave will be a move towards such a society. Instead, it���ll be a mandate for Farage and the inward-looking, reactionary mean-spirited philistinism he embodies.

But was my reasoning sound? It might not be.

I say this not because of Daniel���s claim that Leavers were motivated more by a desire to reclaim sovereignty than to cut immigration: many wanted to take back control precisely because they wanted to cut immigration, whilst others just can���t articulate why they want sovereignty.

Instead, there might be an error here: the association fallacy. Wasn���t I trying to discredit decent Leavers like Andrew and Daniel by association with indecent ones?

Let���s assume I were. Was this necessarily a bad thing?

Sometimes, we can reach the right decision because errors cancel out. For example, the erroneous belief at the roulette table that red is on a roll can correct the error that ���black must be due to come up next���. Or mental accounting can protect us from spending too much through weakness of will by putting some money off limits. In similar fashion, I was trying to use the association fallacy to counter what I saw as wishful thinking by free market Leavers.

But there���s another defence of what I was doing. It���s that the association fallacy might not actually be a fallacy. It���s only one if it commits the sampling error.

Let���s take a clear example of the fallacy: ���You shouldn���t be a vegetarian. Hitler was a vegetarian!��� This fails because of the sampling error: the vast majority of vegetarians are not genocidal maniacs. But what if a disproportionate number were? Wouldn���t this be at least a clue that there might be something wrong with vegetarianism?

In the case of Brexit, the fact that a disproportionate* number of bigots were on the Leave side wasn���t just diagnostic of something wrong with the Leave case. It was also causal. The association of the Leave cause with anti-immigration sentiment invited the government to become hostile to immigrants. Yes, Daniel and Andrew claim that Ms May���s inference is mistaken. But this doesn���t acquit them of the charge of wishful thinking: it is na��ve to hope that governments will do the right, liberal thing.

If you think this is another post about Brexit, you���d wouldn���t be wholly right. When Nick Cohen and James Bloodworth attack Corbyn and the far left for being pro-terrorist and anti-west they are asking me the same question I asked Andrew and Daniel: aren���t my ideals tarnished by association with some bad characters? And the answer is along the same lines. It depends upon proportions: how many such characters are there, and how much power do they have to pervert my intentions?

I don���t know how to answer that. My point is instead merely the trivial one that in a second-best world of bounded rationality and bad people, there becomes much more to politics than simply asserting one���s ideals.

* In saying this, I���m not claiming that all Remain voters are pro-open borders: they are not.

October 11, 2016

Brexit: a worthless experiment

In an attempt to defend the indefensible, Janan Ganesh invites us to regard a ���hard Brexit���* as an experiment.

Sometimes history throws up ideas that are better tested than forever stymied���ideas, unless they are plainly malign or ruinous, have to be held accountable in the end by real-world application. There is only so much mileage in the statecraft of frustrating them.

A ���soft Brexit��� he says would allow Leavers to claim that any ill-effects are due to ���betrayal���, to not implementing Brexit properly. A ���hard Brexit��� would at least permit a proper ���falsification of their project���. And, he adds, if things work out badly we can rejoin the EU.

I���m unconvinced.

This experiment risks imposing real costs on real people ��� lower wages and unemployment. And as Neil Kinnock famously said, ���you can���t play politics with people���s lives���.

This objection, however, won���t work: it only applies to the left.

Instead, I���ve other objections to Janan���s piece.

One is that Brexit is not a scientific hypothesis to be discarded when it is falsified. Instead, Leavers have invested their ego in the idea; I question Janan���s claim that many are ���open to falsification."** This means that if a hard Brexit is followed by economic troubles, they���ll invent immunizing strategies to deny this.

And it���ll be easy to find such strategies. One reason for this is that a ���hard Brexit��� will not be a genuine experiment. In a true experiment, we can compare a treatment group to a control and so discover the effects of the treatment. But after a ���hard Brexit��� we���ll never see the control. We���ll not see the counterfactual, what would have happened if we���d stayed in the EU.

This matters. The case for remain is not that Brexit will lead to catastrophe but that it will cause slower long-term growth; real GDP will grow by a bit less than 2% per year rather than a bit more. If this happens, Leavers will be able to claim that Brexit wasn���t so bad. But this would be entirely consistent with the Remainers being correct.

Also, the Duhem-Quine problem ��� that we often can���t test hypotheses in isolation - is especially severe in this case. Let���s say Brexit leads to slower growth in trade and productivity as Remainers claim. Leavers will find it easy to show other reasons for this. Exporters are ���fat and lazy���; investment has been low; secular stagnation means there���s little innovation. And so on.

And the thing is, these claims will have some truth. There are always many plausible explanations for poor economic performance.

You needn���t look far for an example of what I���m saying. On Radio 4���s Today programme this morning Gerard Lyons ��� one of the more sensible Leavers ��� claimed that a weaker pound was ���inevitable��� because of the UK���s big current account deficit (2���14��� in). That���s a way of denying an effect of Brexit.

I very much doubt, therefore, that a ���hard Brexit��� is a worthwhile experiment. Even if the Remainers are correct abut its effects, most Leavers won���t admit they were wrong.

I suspect instead that Janan is giving us another example of the fact that there is no government policy so bad that it will entirely lack supporters; the corridors of power lend gravitas to even the daftest ideas. As Adam Smith said, ���We frequently see the respectful attentions of the world more strongly directed towards the rich and the great, than towards the wise and the virtuous.���

* I'm putting scare quotes around "hard Brexit" because I take Owen's point that the phrase serves framing rather than purely descriptive purposes.

** Yes, some are. But the better Brexiters such as Daniel Hannan and Andrew Lilico are already having their doubts; I'm thinking instead of fans of a "hard Brexit".

Chris Dillow's Blog

- Chris Dillow's profile

- 2 followers