Chris Dillow's Blog, page 69

December 13, 2016

Tories' target fetishism

There���s a famous story about a nail factory in the old Soviet Union. When it was told to produce millions of nails, it made them so small as to be useless, but when it was told to make tons of nails, it made them so big they were useless*.

I was reminded of this by the Guardian���s report that the government is considering almost halving the number of foreign students coming to the UK.

This is obviously moronic. It would deprive us of billions of pounds of export earnings at a time when we���re borrowing massively from overseas; it would harm one of the UK���s very few world-class high-skilled industries; and it would deprive us of the ���soft power��� than we���d enjoy from future foreign decision-makers having goodwill towards the country as a result of their student experiences.

Why, then, do something so stupid? It���s because cutting student visas is the easiest way of achieving the target of reducing immigration, just as producing useless nails was the factory���s easiest way of hitting its targets.

What we have in both cases are egregious examples of target fetishism. Targets are often not ultimate goals but rather expressions of those goals ��� and sometimes bad ones. What the Soviet Union wanted was more good nails. Similarly, when people say they want to reduce immigration they don���t have in mind an urge to cut the numbers of Chinese physics students. In both cases, chasing the target misses the goal.

And here, I lose patience with the Tories.

Those of us who grew up in the 70s and 80s were told by the Tories that central planning was a stupid idea. And yet here we have a Tory government considering the same mistake that central planners made, of thinking that it was sufficient to hit targets.

But there���s more. What we have here is a failure to see the case for freedom. This is that if you give power to the state it���ll be misused, because the actually-existing state is a stupid bully. Just as ���anti-terror��� laws have been used to harass journalists and peaceful protestors, so immigration controls will hurt decent people. And for the same reason - because they are the softest targets.

There was a time when Tories were, rightly, distrustful of the state. That time has passed. The Tories are now the enemies of freedom, and of basic economic rationality too.

* I don't know if this story is true or not: if it's not, it merely shows that today's Tories are even stupider than Soviet central planners.

December 12, 2016

The productivity silence

Simon recently tweeted that it is important to ask why we are not talking about the crisis of stagnant productivity all the time. He���s surely right: this is our most important economic problem. So why isn���t it a top political priority? The fault, I suspect lies with voters, politicians and the media.

In voters��� case, it���s because stagnant productivity isn���t very salient. ���Some Latvians moved in down the road and now my son can���t get a decent job��� is an obvious story to tell ��� even if it���s wrong. But the UK���s productivity slowdown, and our low productivity relative to other developed countries, is a story about countless things that UK businesses do less well than their French or American counterparts and about impersonal forces such as low investment and innovation, slower world trade growth, a fear of credit constraints, a slowdown in entry and exit and so on. Such things are important, but not vivid.

Reinforcing this is a self-serving bias. People would rather blame their low pay upon immigrants than on the fact that they are incompetent unskilled buffoons.

Herein, though, lies a defect of modern democracy. Because the notion of consumer sovereignty has taken over politics, politicians think that what they���re ���hearing on the doorstep��� matters. In some ways it does. But it can also be a lousy guide to what really matters economically. Few politicians are brave enough to tell voters: ���you shouldn���t worry about that; this is a bigger problem.���

And, of course, the media reinforces this. The BBC takes its agenda from politicians and the press. If these are talking about what are trivial matters economically speaking such as immigration or government borrowing, the BBC will reflect this and so ignore productivity. This is reinforced by three other factors:

- The BBC prefers controversy. A row between idiots ��� one of whom is usually called Nigel ��� is better TV or radio than an expert discussion of productivity.

- Official productivity data comes out only quarterly (though it can be inferred from monthly data), whereas figures on inflation and government borrowing are monthly. This means the news will more often report the latter than the former.

- Productivity is a dry abstract story. The media are much better at human interest stories than in analysing social structures and impersonal forces.

But perhaps there���s something else. Many people do think: ���I���d be better paid if this place weren���t so badly managed���. This sentiment, however, never gets onto the political agenda and the connection from this notion to worker democracy never gets made. Bosses are regarded as the only experts whose competence is unchallengeable. Maybe therefore the relative silence about productivity is yet another example of how managerialism ��� or neoliberalism if you insist ��� has triumphed so totally.

December 7, 2016

The populist paradox

Danny Finkelstein in the Times is good on the need to resist attempts to bully the Supreme Court. He says:

Our institutions ��� parliament, government, the courts ��� must serve a plural society, they must balance interests and protect rights.

The case for doing so lies in large part in cognitive diversity ��� the idea that a plurality of viewpoints is wiser than an individual one. Edmund Burke famously wrote:

We are afraid to put men to live and trade each on his own private stock of reason; because we suspect that this stock in each man is small, and that the individuals would do better to avail themselves of the general bank and capital of nations and of ages (Par 145).

Herein lies a virtue of the rule of law: laws represent the capital of wisdom of ages, and so should act as a check upon our present and perhaps fleeting judgments. Similarly, as Danny says, parliament ���allows diverse representation.���

Which brings me to a paradox. Academic research in recent years ��� inspired by Daniel Kahneman ��� has taught us that Burke was right. Our judgments can be flawed in many ways. Our private stock of wisdom (and knowledge too) is indeed small. We���d therefore expect to see more support for institutions that embody diversity and which check our judgements. And yet the rise of populism represents the exact opposite of this ��� the urge that one���s opinion must over-ride all constraints.

What explains this paradox?

You might object that parliament and the courts aren���t as diverse as Danny says. The former is dominated by PPEist clones and the Supreme Court judges are old, posh and white. This, though, is an argument for ensuring more genuine diversity, not for allowing mob opinion to be unchecked.

Another answer is that academic research hasn���t affected public opinion. Yes, the BBC does broadcast some good programmes about social science. But it is scrupulous in ensuring these are confined to a ghetto on Radio 4 whilst slots which get bigger audiences are filled by speak your branes drivel.

But there���s something else. Increasing academic awareness of the limits of our judgment has been outweighed by the rise of narcissism. Everyone (not just young people) is a special snowflake whose opinion must be respected. It���s this, says Anjana Ahuja, that underpins the populist backlash against science:

Facts and the search for objective truth make up the essence of science; a disregard for the same is not only a hallmark of the new politics but a badge of honour���Why is science under siege? One possible explanation is that it favours objective evidence over subjective experience*.

We see the same thing in Arron Banks��� efforts to teach Mary Beard about the fall of the Roman Empire and Douglas Carswell telling scientists about the causes of tides. As Burke said, ���they have no respect for the wisdom of others; but they pay it off by a very full measure of confidence in their own.��� My readers don���t need telling about the Dunning-Kruger effect or that Daniel Kahneman said that overconfidence is the most damaging and widespread of mistakes ��� but many people still do.

To be clear, my beef here is not so much with what you believe as how you believe it. There is a respectable case for Brexit, though it���s weakening. What is unjustifiable is a fanaticism which wants to over-ride evidence, expertise and traditional institutions. This form of populism is not just a political problem but an intellectual and, dare I say it psychological, disorder.

* She���s writing about populist opposition to climate science. But we saw the same thing years ago when parents refused to give their children MMR vaccinations against the scientific evidence.

December 6, 2016

Why not centrism?

Some people want to revive centrism. Tony Blair wants to ���build a new policy agenda for the centre ground���. And the Lib Dems��� victory in Richmond Park is being seen as a warning to the Tories that it must ���keep the votes of the middle ground.���

This poses the question: does the idea of political centre ground even make sense? It does, if you think of political opinion being distributed like a bell curve with a few extremists at either end and lots of moderates in the middle. But this doesn���t seem to apply today, and not just because political opinion has always been multi-dimensional. What we have now is a split between Leavers and Remainers, and the ideas correlated with those positions such as openness versus authoritarianism. Where does the ���centre ground��� fit into this?

My question is reinforced by the fact that centrists have for a long time defined themselves by what they are not. For years, the Lib Dems biggest selling point was that they weren���t Labour or Tories, and so garnered the protest vote (Oh, such happy days!) This failure to make a positive case seems to have continued. As Ellie Mae O���Hagan tweeted:

I think centrism - whatever it is - could flourish again. But it needs to make a case for existence. And it... isn't.

So, what would such a case look like? The answer, I suspect, lies in a recent speech (pdf) by Mark Carney. (The Bank of England seems to be doing a better job than the main opposition parties). He points out that the gains from trade and technology have been ���uneven���:

While trade makes countries better off, it does not raise all boats; in the clinical words of the economist, trade is not Pareto optimal���For free trade to benefit all requires some redistribution.

This, I think, is the essence of centrism. It accepts that globalization and free markets (within limits) bring potential benefits, but that these benefits must be spread more evenly via the tax and welfare system.

This stands in contrast to nativism and some forms of leftism which oppose globalization and favour market intervention. It also contrasts to libertarianism and Thatcherism which emphasize freeish markets whilst underplaying redistribution.

It���s also what New Labour stood for. It saw that globalization and freeish markets brought benefits, but also that these had to be accompanied by policies such as tax credits to help the low-paid*.

And it���s also conventional economics: markets are good(ish) ways of allocating resources, but not so good at distributing incomes.

This poses the question: what���s wrong with such a vision? Phil says it���s too abstractly technocratic to speak to voters:

The lived reality of voters are erased by the cult of numbers, or replacing the feeling and perception of economic relief by indices measuring GDP, inflation and wage growth. Interest becomes more and more narrowly refined into a bland national interest, expressed in increasing and decreasing metrics assumed to be in congruence with the good life.

I have a slightly different beef. It���s that this form of centrism offers too etiolated a vision of equality. Inequality isn���t simply a matter of pay packets but of power too. Centrism fails to tackle the latter. This is a big failing not least because policies to increase productivity might require greater equality of power in the workplace ��� something which technocratic centrism has long ignored.

It���s become a clich�� that Blair has been discredited by the war in Iraq. I fear, though, that everyone draws the wrong conclusion from that episode. The war wasn���t just a moral failing but an intellectual one: as Chilcot showed, it���s the sort of terrible decision you get when leaders are isolated from ground truth: Fred Goodwin���s takeover of ABN Amro (perhaps the worst economic decision of my lifetime) also falls into this category.

For me, therefore, a centrism which ignores inequalities of power must be inadequate.

Herein, though, lies the sadness: even this form of centrism would be a big improvement upon a lot of today���s politics.

* New Labour didn���t, I think, regard the minimum wage as a device for correcting market failure or for relieving poverty. Instead, it saw it as a way of preventing employers from using tax credits to drive down wages.

December 1, 2016

Elites or people?

The votes for Trump and Brexit have highlighted a division between ���elites��� and the ���people���. For me, though, this is the wrong dichotomy. The question instead is: under what conditions are the people right, and under what conditions are elites right?

Both can sometimes go wrong. Experts are prone not just to professional deformation (pdf) ��� the tendency for perceptions to be warped by their training ��� but also groupthink. For example, the replication crisis ��� which is by no means confined to psychology ��� suggests that peer review fails to weed out poor academic research and might even enhance groupthink.

What���s more, pretences to expertise can often merely be a desire for wealth and power, as Alasdair MacIntyre wrote:

The realm of managerial expertise is one in which what purport to be objectively-grounded claims function in fact as expressions of arbitrary, but disguised, will and preference. (After Virtue, p107)

But on the other hand, we know that the people are often wrong about basic facts, are terrible at understanding connections between economic phenomena, are misinformed by a biased media, and prone to countless cognitive biases.

Rather than always side with the people or always with elites, we should abandon grandiose generalizations and ask in each specific context: who is most likely to be right here ��� the elite or the people? Here are some tests I���d apply.

First, are the conditions in place for the wisdom of crowds to operate? Namely, are individuals��� judgments diverse, uncorrelated and decentralized?

In economic forecasting, I think this is the case. Each individual���s decision on how much to spend is based upon specific private information about his personal future. Aggregate data (pdf) on consumption-wealth ratios thus do a good job of gathering together dispersed fragmentary information about our future prospects. I���d rather trust the crowd, therefore, than economic forecasters.

This isn���t to say the crowd is perfect: spending decisions can be influenced by peers. But nothing���s perfect. The question is one of the relative size of errors.

Secondly, are beliefs motivated by nasty or self-interested preferences?

This can be true of elites. Bosses��� hostility to worker democracy and fund managers��� claims to be able to beat the market owe more to self-interest than fact. George Monbiot says the same is true of oil companies who finance climate change deniers. Equally, though, it can also be true of the public: antipathy to immigration might in some cases be founded upon a dislike of foreigners rather than purer motives.

Thirdly, are there obvious errors and biases at work here?

Everybody ��� expert or layman ��� is prone to cognitive bias. I prefer to look for errors and then ask: what biases might lead people into error?

I suspect this is the case with the public���s belief that immigration has significantly pushed down wages and job prospects. It is due in part to the post hoc ergo propter hoc fallacy (���some immigrants came last year and now I can���t find a decent job���); to the failure to see that immigration can raise natives��� wages by allowing them to do more skilled jobs; and to an ignorance of the myriad other forces depressing pay.

This isn���t to say the public need always be wrong on immigration. If people in areas of high immigration offered factual evidence about (say) how migration is eroding social capital, I would take that as evidence that locals possessed a ���ground truth��� that elites had overlooked.

Relatedly, I���d ask how much effort people have taken to slough off cognitive biases. In David Davis���s case, the answer seems to be: none.

Fourthly, is this a statement of fact or opinion?

It���s possible in theory that the EU referendum might have gathered thousands of fragmentary facts. People might have figured ���the EU stops me doing x, y, or z��� (or facilitates them) and voted accordingly. But this isn���t, for the most part, what we got. Instead, we had a poisonous mixture of racism, lies and hyperbole.

One reason why I favour worker democracy more than plebiscites is that the former is a way of gathering dispersed information - of aggregating marginal gains about corporate performance ��� whereas the latter are not.

Now, I���m not saying these tests are perfect. Nothing is. And we might disagree from context to context on how to apply them. Sadly, however, these tests seem not to be applied in politics. Which is one reason why we see the worst of public opinion being expressed rather than the best.

November 29, 2016

Criminally stupid

There is a point at which stupidity ceases to be a merely intellectual error and becomes a crime. If Nick Cohen is right, the government has crossed this point. He writes:

[David] Davis seems closer in spirit to a bubbly PR girl than a hard-headed statesman. He wants to hear only good news. He wants to see only smiling faces���On no account must businessmen and women say they are worried about Britain abandoning its membership of the single market, the civil servants warn. They needed to ���go into the meeting saying that they were very excited by the possibilities of Brexit. Anyone who felt differently tended to be asked to leave in the first five minutes.

We are living under rulers who do not believe, or at least refuse to trade in, objective fact. Reality is a barrier to the successful implementation of Brexit and must therefore be ignored.

Now, I have a dim view of this government but even I struggle to believe these accusations simply because they are so outrageous - though I fear that the "have cake and it it" memo corroborates them.

I say this because we know that top decision-makers can be prone to at least five cognitive errors*. These are: overconfidence; wishful thinking; the confirmation bias; the planning fallacy; and the tendency to become detached from the reality of what���s happened on the ground. Any good decision-maker should bend over backwards to avoid these obvious errors. If Nick and Ian are remotely correct, however, our government is doing the precise opposite; it is creating a climate in which these errors are actually encouraged.

In an uncertain world, it is impossible to take the best possible course of action. We should, however, be able to avoid the most egregious errors. The Tories seem however to be cultivating them.

This is unforgivable.

For one thing, these errors have been well-known for years. Kenneth Boulding warned (pdf) back in 1965 of the danger of decision-makers ���operating in purely imaginary worlds���. And the research on cognitive biases dates back at least as far as the 1970s and should by now be well-known to anyone who has even a passing interest in the social sciences.

But even if ministers are pig-ignorant of intellectual history ��� which itself is unacceptable - they should at least be aware of the Chilcot report. It showed that the decision to go to war in Iraq was based in part upon errors such as wishful thinking and the confirmation bias. And it warned that positive thinking ���can prevent ground truth from reaching senior ears���.

Success ��� or even basic competence ��� requires that we learn from mistakes. This government, however, seems to be doing the opposite. Instead of learning Chilcot���s lessons, it seems desperate to repeat them.

All this poses two questions. One is: how can people who supported Brexit for years or even decades be so appalling prepared for the process of doing so?

But there���s a bigger question. The point of being a government minister is that you must take decisions. You should therefore at least know how to avoid the worst ones, and be acquainted with the basics of decision theory. But the government seems to fail even in this. Which poses the question: why the hell do they want power if they are unwilling to exercise it with even minimal competence?

* Of course, there are many more. I���m confining myself to those that seem most relevant for now.

November 27, 2016

Not understanding the right

We leftists should make more effort to understand the rise of the populist right, says Janice Tuner in the Times:

After defeat you must ask why. It is easy to blame Breitbart or the tabloids, to label every Trump voter a white supremacist, every Leaver a ���Brextremist���. Easier than asking���what the hell you missed.

Here we must sharply distinguish two different meanings of ���understand���: being aware of the cause of something versus being sympathetic to something. I can do the former without the latter.

For my purposes, perhaps the biggest cause of the rise of populism was pointed out back in 2006 by Ben Friedman. Stagnant incomes, he said, tend to increase support for intolerance. They lead to a rise in right-wing extremism. In the UK, this was exacerbated by the fact that constrained government spending allowed people to blame immigrants for poor public services. This created a demand for change - and people who feel they have lost out are often willing to gamble even on forlorn prospects.

Allied to this is the fact that people feel that they lack power ��� that it is others (���the elite���) that have control, not themselves. As Will says, Vote Leave���s slogan ���take back control��� was a stroke of genius. And Janice quotes approvingly Joan Williams claim that workers disliked Clinton because she reminded them of the professionals who have bossed them around all their lives.

Herein, though, lies a paradox. I have for years been opposing the austerity, managerialism and inequality that have created populism. And I���ve not had much support from those like Janice who now demand that I ���understand��� the right.

But let���s be clear here. Trump and Farage do not understand the working class. They come from immensely privileged backgrounds, have spent little time studying the real problems workers have, and make no effort to identify genuine circumstances where the people might be right and elites wrong. Instead, they are just narcissists who found a ready market for their bigotry thanks to helpful socioeconomic conditions, a complicit media and cognitive biases among voters.

There���s nothing much to understand here, because there is simply no credible evidence that their proposed policies will actually help workers (other than Trump���s fiscal expansion). It���s hard to engage with a vacuum.

This is especially true because, as Nick Cohen points out, there is in fact an intellectual crisis on the right.

In my lifetime, we Marxists have faced three different types of opponent on the right. First, there were those who were sceptical of grand theories such as Burke and Oakeshott; think of Popper���s critique of Marx in The Open Society and its Enemies. Then there was neoliberal Thatcherism. And now there���s populism.

But these different iterations are opposed to each other. Populists��� supposed concern that immigration is reducing the cohesion of traditional communities sits uneasily with the fact that Thatcher���s attack on miners destroyed such communities. And their assertion of the ���will of the people��� flatly contradicts Burke���s view that MPs should over-ride the poor judgement of voters.

These iterations have very little in common, except perhaps a hatred of freedom and equality.

And you want me to understand this? To quote Thatcher: no, no no.

November 25, 2016

Forecasting GDP

The OBR���s downbeat forecasts for the economy have caused Brexiteers to question its competence. For example, Iain Duncan Smith says it has been ���pretty much been wrong on everything.��� Such attacks miss two important facts.

Fact one is that there is a crucial difference between unconditional and conditional forecasts. A conditional forecast is the sort that says: ���if you put your hand in the fire you���ll get burnt.��� An unconditional forecast says ���you���ll get burnt���. These are obviously two different things.

Personally, I think unconditional forecasts - the sort that say ���GDP will grow 1.4% next year��� - are pretty much worthless and simply bring economics into disrepute.

But this isn���t the issue here. Instead, Brexiteers��� beef is with the OBR���s conditional forecast ��� with its claim that:

Over the time horizon of our forecast any likely Brexit outcome would lead to lower trade flows, lower investment and lower net inward migration than we would otherwise have seen, and hence lower potential output.

Is this claim wrong? Attacks upon the OBR���s record at unconditional forecasts are just childish ad hominem arguments that are irrelevant ��� not least because the OBR���s view is shared by so many others.

Better arguments would be that Brexit would permit freer trade (as Gerard Lyons still believes) and that this, plus sterling���s fall, would boost GDP growth.

Personally, I doubt this. But what���s the evidence?

You could argue that today���s figures showing a better than expected rise in business investment in Q3 is consistent with Brexiteers��� optimism; it might show that industry is indeed tooling up in anticipation of higher demand.

But here comes my second fact. It���s not just pointy-headed experts and elites that are gloomy about the economy. So too are the people.

The thinking here is simple. Households��� decisions on how much to spend should be forward-looking: if we anticipate good times, we���ll spend more than if we expect bad.

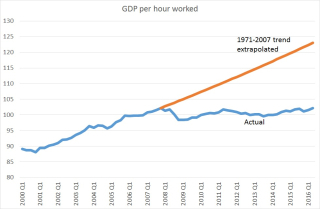

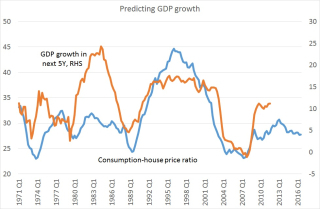

And this thinking is correct, to some extent. My chart shows that the ratio of consumer spending to house prices (a rough proxy for spending-wealth ratios) has predicted medium-term GDP growth in the past. Low spending in 1973, 1979, the late 80s and mid-00s all led to slower GDP growth, and high spending in the mid-90s led to decent growth. Since 1971 there���s been a correlation of 0.63 between the consumption-house price ratio and subsequent five-year growth in real GDP.

Which brings me to the punchline. This ratio is currently below its post-1971 average, which points to below-average GDP growth. Not catastrophic, note ��� merely below average. In fact, if post-1971 relationships hold, this ratio predicts GDP growth of 1.8% per year until 2021 ��� which, coincidentally, is exactly the same as the OBR forecasts.

Now, you can quibble with this, not least because there is of course a margin of error in this relationship. Brexiteers might argue, I suppose, that because consumer spending is partly shaped by habits it hasn���t yet fully responded to the good news of the Brexit vote. Such a hypothesis implies that spending should rise a lot in coming months. Let���s see.

For now, though, this leaves Brexiteers with a problem. It���s not just the experts they so despise that are downbeat about the economy. So too are those founts of all wisdom, the people.

November 24, 2016

Populists as snake oil sellers

Simon wonders why disenchantment with globalization has caused people to turn to what he calls snake oil salesmen. That phrase is apt, because snake oil salesmen thrived for decades. And some of the reasons they did so might be relevant today.

My source here is a wonderful paper (pdf) by Werner Troesken which describes the massive growth in patent medicines in 19th century America. This suggests to me four points of similarity between snake oil salesmen and populist politicians.

First, patent remedies weren���t entirely ineffective. They often contained alcohol or opium which gave people at least a short-term pep. As Ran Spielger shows (pdf), if people mistake this short-term boost for a genuine cure (which is especially likely if their ailment would have cleared up anyway) then demand for quacks will grow. In this tradition. Trump is mixing harmful anti-globalization policies with a helpful fiscal stimulus.

Secondly, the very fact that patent medicines failed to eradicate chronic ailments meant that the market for them grew over time as more people got ill. And ill people are desperate, and willing to take risks. Troesken quotes Albert Prescott, a chemistry professor writing in 1881:

Just as men driven to straights will put their last pittance into the lottery instead of the savings bank���so, with the better excuse of bodily prostration and nervous restlessness, against his own judgement, and suffering with a glimmering apprehension of the wholly unscrupulous character of the human harpies who practice on his credulity, the sick man tries one game of chance among the unknown remedies.

This, of course, expresses an element of prospect theory ��� that people facing losses take risks. And this same thing helps explain the rise of populism: people who feel they are losing out from the existing order gamble on change.

Thirdly, patent medicine sellers devoted huge efforts to marketing ��� an effort which consisted of gross over-hype, claiming their products to be ���most efficacious in every way.��� Troesken says:

Why promise to cure just one disease, and unnecessarily limit your market? Promise to cure everything, and more people try the product���the more vile, painful, and incurable the disease, the better. Similarly, do not just claim to make the patient feel better, promise a full blown cure.

Genuine doctors were powerless against this sales drive, because ill-informed customers could not distinguish between quality and quackery. Troesken says:

The high-cost provider would have trouble signaling high quality through advertising because all providers, even the low-quality ones, are using their advertising to signal high quality. Consumers would therefore discount the claims of the high-quality provider just as much as they discount the claims of the low-quality, dishonest provider���.The���physician might have also told the patient: ���don���t waste your money on patent medicines; they will not be able to cure you either.��� But absent some independent authority telling patients that the physician knew more than the advertiser of patent medicines, it is not clear why patients would have attached any more meaning to such a statement than they attached to advertisements

There���s a direct parallel between this the inadequacy of the media today. The BBC���s decision to become impartial between truth and lies means that the ���independent authority��� that might help people distinguish between quacks and experts is indeed absent.

Finally, quacks succeeded by denying that proper doctors had any genuine expertise ��� a denial aided by the fact that their expertise was indeed limited*. Troesken quotes Scribner���s Monthly from 1881, a magazine which advertised patent medicines, despite objections from physicians:

There is no such thing as medical authority���. The people are, and are obliged to be, the only judges of medicine and of physicians

When Jacob Rees-Mogg says that ���experts, soothsayers, astrologers are all in the same category��� he is simply echoing a 19th century shyster ��� a fact which perhaps won���t surprise you.

My point here is simple. There���s nothing new under the sun. Simon is dead right to liken populists to snake oil salesmen because both use similar methods.

And the methods work. Liberals like to think that in the marketplace for ideas, good ideas will beat bad ones, just as in the marketplace for products good ones will displace bad ones. History, however, warns us that in both cases, it isn���t necessarily so.

* You might see another parallel here with today���s debate between elites and populists.

November 21, 2016

Why not worker-directors?

I���m disappointed but not surprised that Theresa May has backtracked on the promise to put workers onto company boards. But let���s be clear why I���m disappointed.

A single worker-director would not greatly empower workers ��� although of course it might be a stepping stone towards a greater voice. Sam might be right to say that giving workers shares might be a better alternative.

Instead, I favour worker-directors not so much because I'm a socialist but because I'm a libertarian. I support them for the same reason that I support free markets (in some contexts) and free speech. It���s because I believe in cognitive diversity. Worker-directors would increase boardroom diversity ��� not least by bringing ground truth to the table ��� and thus improve decision-making. The more intelligent fund managers see this. This is what Aberdeen Asset Management told the BIS select committee:

There is a significant body of evidence showing that mixed teams make better decisions. The best boards feature a mix of gender, ethnicities and socio-economic backgrounds. Any board that believes it cannot be enhanced by the inclusion of views from significant parts of society is clearly suffering from closed minds in more ways than one.

This is especially the case because worker-directors have skin in the game. Workers are more exposed to the risk of the company doing badly than are outside shareholders, and so have a big incentive to ensure it is well-managed. As Tom says:

Employees have far more firm-specific risk than investors, and are acutely aware of the need to act in a way that does not damage their known "investment" in the business. In contrast, especially where the "shareholder" is an intermediary, investors have far less at stake in any given company, and can often act in a very short-term fashion to their own benefit.

I���ll concede that these arguments run into a problem. Evidence from Germany ��� where worker-directors are more common ��� suggests that their effect upon corporate performance is mixed: see, for example, this survey (pdf) by John Addison and Claus Schnabel.

This, though, might disguise the fact that there is a (large) subset of firms where worker-directors do make a positive contribution. These are in firms where workers are skilled and informed. Larry Fauver and Michael Fuerst say (pdf):

Labor representation increases firm value by acting as a conduit for the flow of information���On an operational level, it is arguable that labor has a unique perspective on the costs of production, especially those related to worker hours. A labor presence on the board consequently provides unique insight into project feasibility and therefore improves corporate decision-making.

They show that in higher-tech industries, worker directors do indeed increase shareholder value.

All this brings me to a paradox. Theresa May believes we should listen to the ���will of the British people��� even when this conflicts with expert opinion. And there are times when this is correct. Sometimes, the people do indeed know more than experts: this is the case if knowledge is dispersed and fragmentary or if the people know ground truth better than experts.

And as I���ve said, these conditions are more likely to be satisfied in workplaces than was the case in the Brexit vote. Which poses the question: how can Ms May favour giving people a voice in some circumstances but not in others, when that voice is likely to be an informed one?

The answer, I fear, is simple. Ms May wants to hear the people���s voice not out of a belief in the wisdom of crowds, but because she���s simply a populist. She want to hear the worst of people���s voices, not the best.

Chris Dillow's Blog

- Chris Dillow's profile

- 2 followers