Chris Dillow's Blog, page 70

November 20, 2016

On class politics

Trump���s election victory has led to calls to bring class back into leftist politics. ���Class trumps gender, and it���s driving American politics��� says Joan Williams. Sam Dale attacks the ���toxic failure of identity politics��� and says ���Liberal elites have no clue about the lives of the working class. They should learn.��� John Gapper writes that the resentment that led to Trump and Brexit ���seems to me to originate on the factory floor.��� And Mark Lilla writes:

The fixation on diversity in our schools and in the press has produced a generation of liberals and progressives narcissistically unaware of conditions outside their self-defined groups, and indifferent to the task of reaching out to Americans in every walk of life.

Of course, I applaud this re-assertion of class ��� which, in generals if not specifics, applies equally to the UK. We must, however, distinguish between a good and bad way of bringing class back into politics.

The bad way is to regard the ���white working class��� as yet another ���demographic��� to be catered to by marketing politics, often by claiming to heed their ���legitimate concerns��� about immigration.

I fear this would fail in its own terms: workers don���t trust politicians who look like their bosses and who claim insincerely to care about their concerns.

But it fails in other ways. The very notion of a ���white��� working class plays the ruling class���s game of divide and rule. This isn���t just because it pits class politics against identity politics, but also because it imputes a racism to workers which is perhaps just as prevalent ��� and more damaging ��� among the boss class. It downgrades the many other genuine problems workers have, such as stagnant wages, insecurity and workplace tyranny. And it has the absurd implication that ethnic minorities aren���t part of the working class too.

There is, however, a more intelligent form of class politics. This starts from the fact that class isn���t a state of mind but an objective fact: if you���re in a position of subordination to an employer, you���re working class whatever you feel. This means that being working class unites otherwise disparate people. The immigrant chambermaid, the skilled coder whose boss is a twat, and the academic facing the neoliberalization of the university are all working class.

This means they have some common interests. All would benefit from increased control in the workplace and increased bargaining power.

In this sense, class politics should be a unifying force. And there needn���t be a conflict between class politics in this sense and identity politics, for at least three reasons:

- The same fuller employment and anti-austerity policies that would benefit workers would also help reduce gender and ethnic inequalities. In a tight labour market, employers will have less power to indulge racist and sexist attitudes.

- Faster growth in real wages would foster a climate of tolerance of diversity. This year���s events in the UK and US have vindicated Ben Friedman���s point that economic growth breeds liberalism and stagnation creates intolerance and racism.

- The same high basic income that increases workers��� bargaining power is also (pdf) a feminist policy, both because it valorizes what has traditionally been ���women���s work��� outside the marketplace, and because it gives women the ability to flee abusive relationships.

Of course, all this is easier said than done. One challenge for the left ��� which is as great today as in Marx���s time ��� is to build class consciousness. Politics isn���t just a marketing exercise aimed at getting our person into office. It���s about building a constituency for intelligent class politics. This is a long game.

But let���s remember the underlying fact here. The interests of the working class are, to a fair extent, the interests of most people. In this sense, the working class is not a problem in politics. It���s the solution.

November 17, 2016

Ideology in economics

Much as I admire both protagaonists, the debate between Simon and Jo on the role of ideology in economics left me cold. I���m not interested in whether economics is mainstream or heterodox.

To see my point, let���s take an example from outside macro ��� the capital asset pricing model. This is an elegant, internally consistent and well micro-founded theory.

And it���s wrong. In particular, we���ve known since the first tests of it that low-risk stocks do better than they should. This is weird: theory tells us there should be a trade-off between risk and return, but the facts tell us otherwise.

Herein, for me, lies the essence of economics ��� the collision between theories and facts.

There���s a parallel here between the CAPM and (some?) RBC models. Both are theoretically elegant. And both fail to survive contact with the real world. Just as the great performance of defensives undermines the CAPM, so the existence of involuntary unemployment rejects RBC theories: the unemployed are significantly less happy than those in work ��� and in fact unhappier than the divorced or disabled.

But why is the CAPM wrong? There are some nice theories (pdf). But I want to draw your attention to a recent paper by Michael Ungehauer and Martin Weber at the University of Mannheim which I think is a model of good economics.

They show that a key assumption of the CAPM is wrong. The CAPM assumes that investors measure market risk by beta, the covariance of a stock with the market. But Ungehauer and Weber show that people don���t measure risk this way. Instead, they assess correlations by using a simple counting heuristic: how often does a stock co-move with the market? This leads to different measures of risk, because it underweights the importance of large price moves.

They established this first by experiments. Then they applied their theory to US data. And they found that if stocks��� riskiness is measured by the frequency of co-movement with the market, there is indeed a trade-off between risk and return. It���s just that, contrary to the CAPM, risk isn���t measured by beta.

In this sense, there���s another analogy between the CAPM and RBC theory. The CAPM says that agents��� view of risk is determined by beta; RBC theory says their view of the future is determined by rational expectations. For me, both claims must be tested against the facts.

I appreciate that I might just be expressing a personal taste here, but I don���t give a toss whether a theory is elegant or not, or mainstream or not. For me, what matters is: does it fit the facts? And: does it work? My response to elegant theories is often like that of Andrew Tyrie to Boris Johnson: ���This is all very interesting, Boris. Except none of it is really true, is it?���

Now, you might find this surprising. We Marxists are supposed to be spittle-flecked ideologues, and yet here I am demanding facts and utility.

But of course, there���s no paradox at all. As a Marxist, I have no skin in the game of whether the CAPM or efficient theory is right or not: such matters are orthogonal to my concerns qua Marxist. And in fact even if Robert Lucas���s main points were right ��� that business cycles are an optimum response to technology shocks with little welfare cost ��� a lot of Marxism would survive. Such claims are consistent with the notion that capitalism is exploitative and alienating and leads to unacceptable inequalities of wealth and power.

It���s sometimes said that Marxism brings ideology into economics. For me, though, it takes it out.

November 16, 2016

On the doctrine of signatures

In pre-modern times, people believed in the doctrine of signatures. This was the idea that the cure for an ailment must resemble the ailment itself. So, for example, eyewort was used as a remedy for vision problems and toothwort for toothache because the flowers of those plants resembled eyes and teeth. As Thomas Gilovich and Kenneth Savitsky write:

Historically, people have often assumed that the symptoms of a disease should resemble either its cause or its cure (or both). In ancient Chinese medicine, for example, people with vision problems were fed ground bat in the (typically) mistaken belief that bats have particularly keen vision and that some of this ability might be transferred to the recipient (p685 of this big pdf).

There was just one problem with this ��� it was wrong.

However, although modern medicine has corrected this error, we still see it in economic policy. What Gilovich calls the ���like goes with like��� dominates popular attitudes to economic policy. For example:

- American voters who believe cheap imports have depressed domestic wages support the introduction of tariffs.

- People who believe (mostly wrongly) that immigration has depressed wages favour immigration controls.

- Leftists support higher minimum wages as a solution to low pay.

- People blame the Bank of England for low interest rates rather than global secular stagnation or tight fiscal policy.

In these cases we see a modern version of the doctrine of signatures ��� the belief that the cure must resemble the ailment. So higher import prices are the solution to cheap imports; higher minimum wages the solution to low pay; monetary rather than fiscal policy is to blame for low interest rates, and so on.

And just as the doctrine of signatures was wrong in medicine, so it is in economics. Even if tariffs or minimum wages would do some good, there are better alternatives. To the extent that immigration or cheap imports raise inequality, a better solution might be more redistributive tax and benefit policy. And it���s better to help the low paid by increasing demand for labour through expansionary macro policy and by increasing their bargaining power than by minimum wages or immigration controls.

So, why don���t people appreciate this sufficiently? It���s not just the lousy lying media that���s to blame. It���s because the same representativeness heuristic that underpinned belief in the doctrine of signatures is also at work here: people believe that effects must resemble causes. They are, David Leiser and Zeev Kril have shown, bad at connecting economic phenomena. Instead, says Leiser, public attitudes to the economy are shaped by a ���good begets good��� heuristic (pdf) ��� the idea that good things have good effects. That���s very similar to the ���like goes with like��� heuristic described by Gilovich and Savitsky.

I fear, however, that this is a case where diagnosis is easier than cure. It���s easy to see that popular attitudes to the economy are mistaken, but much less easy to see how they might be corrected, especially when so many people have an interest in not correcting them. It took the medical profession centuries to rid itself of the doctrine of signatures. It might take as long for public attitudes to economic policy to improve.

November 15, 2016

Tariffs vs exchange rates

The apparent popularity of Donald Trump���s demand for protectionism raises a question: why haven���t exchange rates done the job they were supposed to?

I ask because one justification of floating exchange rates back in the 1970s was that they would render protectionism redundant. If a country ran a trade deficit, the thinking went, its exchange rate would fall, thus improving its competitiveness and pricing its workers back into jobs. As one of my old textbooks put it:

If the exchange rate is free continually to equilibriate the balance of payments, a country���s policy-makers should not have recourse to protectionist devices for balance of payments reasons: the freeing of exchange rates should usher in a period of more liberal trade (Ronald MacDonald, Floating Exchange Rates, p4)

For a long time, this looked valid: trade barriers have indeed fallen since the 70s. So, why is there now a call for tariffs rather than for exchange rate adjustment?

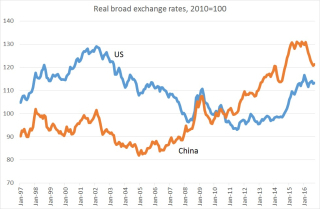

You might think the answer is simple: China has fixed its exchange rate to keep it artificially low and therefore its exports cheap.

But this isn���t entirely true. China has fixed its nominal exchange rate. But because it has had higher inflation than elsewhere, its real exchange rate has risen a lot ��� by over 40% in the last ten years according to BIS estimates.

You might think that even this appreciation hasn���t been sufficient: perhaps the US���s status as a reserve currency under the ���Bretton Woods II��� system has sustained demand for dollars and so prevented the US dollar falling as much as it should.

Maybe ��� although this overlooks the fact that the US���s lack of competitiveness because of high wages is greatly offset by the advantage it enjoys of cheaper energy.

But perhaps there���s another reason. Maybe exchange rates don���t equilibriate the balance of payments after all. Let���s suppose China were to greatly revalue its currency? Would more expensive Chinese exports thereby improve the lot of US workers? Yale���s Ray Fair has used his econometric model to answer this. His finding is that:

The net effect of the yuan appreciation on U.S. output and employment is close to zero���in fact slightly negative. (p194 of this pdf)

There are two reasons for this. One is that a rise in the yuan would cut China���s output generally, and this would reduce US exports. The other is that dearer Chinese imports would raise the prices faced by US consumers, thus reducing their real incomes. These factors offset the tendency for a dearer yuan to make US goods more competitive.

This suggests that there might be a grain of truth in the call for tariffs, insofar as exchange rate adjustments don���t work.

But of course, only a grain. There are many better ways of helping unskilled workers: looser macro policy, welfare reform, a jobs guarantee and so on. Such policies have the added virtue of protecting such workers from the myriad (and I think greater) other threats to their livelihoods.

Rather than say this to endorse Trump, I do so to attack the mainstream. The presumption that free markets and floating exchange rates would protect workers from cheap imports might well have been wrong, and it distracted attention from the need for policy interventions to help the (minority of) workers hurt by them. In this sense, Trump���s victory represents a failure of centrist policy-making.

November 14, 2016

Ed Balls & modern "politics"

Ed Balls��� performances on Strictly Come Dancing shed more light upon politics than is generally appreciated.

What I mean is that Balls the politician was presented as an unsympathetic figure. ���Bruiser��� and ���bully��� were common descriptions, and his coining the phrase ���post-neoclassical endogenous growth theory��� gave the impression of being a pointy-headed technocrat. He embodied the Oxbridge elite that is supposedly out of touch with the common man.

And yet on Strictly his performances have been ���a rare delight to brighten our weeks���. He���s charming, popular and funny: we���ve been laughing with him, not just at him.

Which poses the question: how can there be such a massive difference between Balls the politician and Balls the dancer?

It���s tempting to blame the media. After all, the same journalists who painted so unsympathetic portrait of Balls also made a public schoolboy who doesn���t listen to music or watch TV into a man of the people, and a serial liar and friend of a criminal into a loveable buffoon. The BBC, of course, has been complicit in this misrepresentation, and remains so: just listen to how John Humphrys usually aggressive interview technique deserted him this morning (2���09��� in) when faced with a Trump crony.

But perhaps there���s something else. Balls the politician made a terrible mistake. It���s the same error Ed Miliband is making when he calls upon the left to ���rebuild with deep thinking���. This mistake is to take politics seriously.

Doing so has two costs. One is that being serious commits you to some principles and a vague commitment to the truth as you perceive it. This puts you out of touch with ordinary voters with your truth conflicts with theirs, and makes you inflexible. By contrast, the Tories lack of interest in ideas allowed them to shift from being a party of the metropolitan elite to appearing as a sort of Ukip-lite. And it enabled Trump to tell his voters what they wanted to hear, regardless of whether he can or will enact his promises.

The other cost is that it means you come across badly on TV. If you prepare well for interviews and try to make serious points, you���ll look humourless and out of touch. The Johnson cheeky chappie approach works better.

Political success is achieved today by treating public life as a game, as a jolly jape. Taking it seriously destines you to failure.

Again, the BBC is complicit in this. It invited Marine Le Pen onto the Marr show not out of a deep interest in French politics but because it knows that fascism sells. It booked Le Pen rather than Alain Juppe (the favourite to be next president) because it thought it would be ���good TV���. And it rewards politicians like Johnson who play along with this aim.

The idea that the BBC���s politics output is high-minded is nonsense. It is part of the entertainment business just like Strictly is. The difference is that Strictly is good entertainment.

November 13, 2016

On Burkean Marxism

���We are afraid to put men to live and trade each on his own private stock of reason; because we suspect that this stock in each man is small, and that the individuals would do better to avail themselves of the general bank and capital of nations and of ages.��� Commenters on a recent post of mine have pointed out that my awareness of individuals��� limited cognition echoes that famous claim of Edmund Burke, and wonder how a Marxist can express such a sentiment.

The question���s a good one. Anyone who doesn���t feel the force of Burke���s point is a bumptious prat who knows nothing of history, politics or psychology. If Burke and Marx are incompatible, that���s bad for Marx.

But are they incompatible? Perhaps not.

First, a distinction. We Marxists are fighting both defensive battles (against inequality and reaction) and offensive ones. In the defensive battles, we are and have been certainly on the side of Burke whilst the right is against him. For example, Harry Braverman���s account of deskilling by Taylorite management is a defence of traditional craft knowledge against a form of rationalism. Our support of coal mining communities against the Thatcherite attack in the 1980s was a defence of Burkean small platoons against sophists and calculators. And our resistance to the managerialist-neoliberal attempt to revolutionize universities is a Burkean defence of tradition against arrogant know-alls.

In these respects, Marxists are the Burkeans and neoliberals and Tories have been the anti-Burkeans.

There���s more. One reason why I���m a Marxist is that I doubt that capitalism can be greatly improved by moderate reforms. That arises from a Burkean scepticism about rationalist scheming.

Which runs into the question: isn���t communism the most hubristic rationalist scheme of all? Isn���t there therefore a flat contradiction between Marx and Burke?

Not necessarily. Except for a few policy proposals in the Communist Manifesto (some of which were subsequently enacted) Marx notoriously did not provide a blueprint for a communist society and was rude about those who did. Instead, he wrote:

We do not anticipate the world dogmatically, but rather wish to find the new world through the criticism of the old���We do not confront the world in a doctrinaire way with a new principle: Here is the truth, kneel down before it! We develop new principles for the world out of the world���s own principles.

Burke wrote that ���the individual is foolish, but the species is wise��� ��� a claim we now know to be true only under special conditions. You can read those words of Marx as seeing the process of socialism as an attempt to unlock the wisdom of the species.

Many leftists today think of the transition to socialism in these terms. Erik Olin Wright has written (pdf) of ���interstitial transformation��� ��� building and then expanding socialistic institutions. In this spirit Paul Mason has written:

Capitalism, it turns out, will not be abolished by forced-march techniques. It will be abolished by creating something more dynamic that exists, at first, almost unseen within the old system, but which will break through, reshaping the economy around new values and behaviours.

In this sense, the transition to socialism will be a modest process of trial and error. That���s consistent with a Burkean scepticism about our ability to foresee what will work.

There���s something else. A big gripe Marxists have with capitalism is that it is a system of domination; in the workplace and in politics, only a few have effective power. By contrast, under communism such domination will cease; communism is a society ���in which the free development of each is the condition for the free development of all.��� In this sense, communism replaces the rule of foolish individuals with that of the wise species. It therefore facilitates Burkeanism in a way which capitalism cannot.

Of course, Burkean epistemology has often been used as a tool of reaction and conservatism. But it needn���t be so.

November 11, 2016

Is globalization to blame?

Donald Trump���s victory is being seen as a backlash against globalization. For me, this poses the question: to what extent is globalization to blame for the decline in many workers��� real incomes?

The answer, I suspect, is: not much. These papers by Ann Harrison and colleagues (pdf) and Jonathan Haskel and colleagues (pdf) show that it is very hard to link declining US real wages to increased openness to trade. Equally, it is unproven (to say the least) whether increased immigration has contributed to falling wages: George Borjas���s claim that it is has has been sharply challenged (pdf).

Common sense should also make us doubt whether globalization is to blame.

For one thing, cheap imports should help workers. If you���re spending $5 on a Chinese T-shirt rather than $10 on a US-made one, you���ve got $5 more to spend on other things. That should increase demand and jobs. And insofar as it cuts inflation, cheaper imports should allow real interest rates to fall ��� which should increase economic activity and jobs. And this is not to mention that globalization has probably cut interest rates in another way since the 1990s, thanks to the Asian savings glut.

Such doubts about the adverse effects of globalization are reinforced by casual empiricism. The pace of globalization ��� measured by growth in world trade - has slowed markedly since the financial crisis. But US real wages, until very recently, haven���t improved. This tells us that other things might have depressed wages of ordinary Americans.

What might these be? Here are seven other suspects (there might well be more), some of which date back years and some of which are more recent:

- The decline of trades unions. This has increased inequality not just by depressing workers��� pay (pdf), but by increasing bosses' pay by weakening one constraint upon their rent-seeking.

- Financialization. For example, increased corporate debt, especially in the 80s and 90s incentivized firms to cut costs aggressively. Englebert Stockhammer estimates (pdf) that this was a more important factor in depressing the share of wages in GDP than globalization.

- Skill-biased technical change (pdf). Since the 1980s, new innovations have increased demand for skilled workers rather than for unskilled ones.

- Power-biased technical change. Innovations such as CCTV, containerization and computerized tills have given managers more direct oversight of less-skilled workers, which has removed the efficiency wage element of their pay.

- Lower minimum wages. The real value of the US minimum wage is 20% lower now than it was in the 1970s.

- A meaner welfare state. In incentivizing people to find work, cuts in welfare benefits have reduced wages by increasing labour supply and weakened workers��� bargaining power by worsening their non-work options.

- The productivity slowdown. In the last five years��� labour productivity has grown by just 0.7% per year, compared to 2% per year in the 30 years before the 2008 crisis.

All this poses a paradox. Although the economic evidence suggests that globalization is, at most, only one of many contributors to the declining fortunes of middle America, it has dominated the political debate to the exclusion of those other factors. Why might this be? At least part of the answer is that it suits some people very well for foreigners to get the blame rather than for inequality and the health of capitalism to come under scrutiny.

November 10, 2016

Does character matter?

Trump���s election victory has been regarded as a defeat for pollsters and the liberal elite. But there���s another group who should worry about it ��� HR managers. This is because Trump���s presidency is a big and public test of a hypothesis: of whether past character predicts job performance.

Imagine you were hiring a senior manager. The following candidate pitches up. He has no directly relevant past experience: Trump has never held elected office. He has little understanding of what the position entails; Trump���s grasp of the constitution is shaky. His past business management has resulted in several bankruptcies and unpaid debts. He has confessed to sexual harassment. And this is not to mention the narcissism and sociopathy.

Many HR managers would tell us they wouldn���t let such a candidate through the door.

Which poses the questions. How, then, can Trump be anything other than a disaster as president? If he isn���t wouldn���t this suggest that all the effort spent screening candidates is a waste of time and money? Why not just pick them at random? (I suspect the median American is of better character than Trump).

The answer to this lies in the possibility that Trump���s character might not be a complete liability, in at least three ways:

- In a president, being representative of the people, who themselves are ignorant and prejudiced, is desirable. There���s something in the Bill Stone theory of democracy.

- There are checks and balances. Not only are there constitutional constraints on what the president can do, but the president also has access to the best advice, if he wants it. Mervyn King said that being Governor of the Bank of England ���is actually the easiest job I���ve ever done���you���ve got tremendous support.��� Whilst this isn���t entirely true of the presidency ��� he���ll find lots of opposition! ��� he can have a strong support network to smooth out the impact of his character flaws.

- Policy matters more than character. If Trump can invest well in infrastructure and simplify the tax code whilst his promises on protectionism and immigration control get diluted, he might not be an unmitigated catastrophe.

Psychologists believe there is only a weak link at best between measurable personality traits and job performance. And the fundamental attribution error cautions us that we often over-rate the importance of personality and under-rate that of the environment. Let���s hope Trump���s opponents are making this mistake.

Now, I must caveat this. A big part of why character matters is that it might help predict how a man responds to surprises. If we���re lucky, the surprises a Trump administration gets will not highlight his flaws. (If were��� not���)

Nevertheless, there is an important question here that applies far beyond Trump: how far does character matter? Mightn���t policy and circumstance matter more? Can personality be restrained or enhanced by institutions?

The answers, of course, differ from time to time, place to place and job to job. It is insofar as such differences exist that a successful-ish Trump presidency would not invalidate traditional hiring practices. But then again, plenty of narcissists and psychopaths do become CEOs. So perhaps the American electorate isn���t so different from HR bosses after all.

November 9, 2016

My Trump fear

There���s one man whose work seems to be vindicated this morning ��� that of Ben Friedman. Back in 2005 he wrote (pdf):

Economic growth���meaning a rising standard of living for the clear majority of citizens���more often than not fosters greater opportunity, tolerance of diversity, social mobility, commitment to fairness, and dedication to democracy���But when living standards stagnate or decline, most societies make little if any progress toward any of these goals, and in all too many instances they plainly retrogress.

The election of Donald Trump seems to confirm this theory. It is perhaps the most morbid symptom of secular stagnation.

Now, I appreciate there���s some resistance to this idea. A Gallup poll has found that Trump���s supporters are reasonably well-off ��� albeit not as much so as the finding that his supporters in the primaries have an average household income of $72,000 would suggest. And Ezra Klein points out that Trump supporters (like Brexit voters) tend to live in areas of low immigration.

Such facts, though, are consistent with Jason Brennan���s theory that voters are sociotropic: they vote not in their personal interest but in the national interest as they perceive it. And as Simon says, these perceptions are distorted by media lies.

Those lies, though, contain a germ of truth ��� that median incomes have been stagnating for years. Although they have picked up recently, they are still below their late 90s levels*. Trump has exploited the anxiety that this stagnation has generated ��� for the country if not so much for his individual voters' pocketbooks.

Which brings me to my fear. What if Trump proves unable to reverse this stagnation? What if protectionism (and the fears thereof that might depress business investment) and tough immigration controls depress incomes by more than looser fiscal policy raises them? Or what if the forces of secular stagnation simply keep income growth down?

It would be nice to think that, in such an event, voters would infer that closed borders are the wrong way to reverse stagnation and that more liberal egalitarian methods must be tried instead and so there���ll be a backlash against Trump.

This, though, is na��ve. When people are confronted by evidence that contradicts their beliefs, they often do not revise those beliefs but instead double down on them and become more dogmatic: this is the backfire effect or asymmetric Bayesianism. Picture the scene in 2020:

Fact: the US economy has performed poorly.

Response: ���This only shows that we haven���t done enough to protect the economy from cheap foreign competition or to reduce immigration. We need to get tougher.���

This, surely, is more likely to be the response of Fox News than an admission of failure. As Max says:

Trump might satisfy some of his base (as Tory Brexit will satisfy to some extent the ���left behind��� in this country) but nothing will ever satisfy the true believers, because while we can do more to stimulate domestic industry and control immigration we cannot reverse time or socially engineer a lost country. There will be more bitterness, more resentment, more backlash.

Normally, political partisans hope that their opponents fail in office. Such a hope should be resisted. A successful Trump presidency might be as unpleasant as it is unlikely. But I fear that a failed one would be worse.

* The recent pick-up is consistent with Friedman���s thesis, if it is long periods of growth or the lack thereof that influences ideology rather than shorter-term fluctuations.

November 8, 2016

The opportunity cost of Brexit

There���s one possible effect of Brexit that I suspect hasn���t had the consideration it merits ��� the opportunity cost.

What I mean is that all of us ��� politicians, journalists and regular folk ��� have limited attention and mental resources. Attention devoted to Brexit is therefore attention that���s taken away from other matters. And given that state capacity is also limited, if our best civil servants are working on Brexit (which is an if) then they are not focusing on other policies. Brexit steals cognitive bandwidth.

For example, in a better world, we���d devote our political attention to overcoming secular stagnation, welfare reform, combating inequalities of power and income, improving workers��� rights and so on. As it is, attention is focused on trade deals, our relationship with the single market, countless treaty renegotiations and so on ��� all of which are efforts merely to avoid losses, something which could have been more simply achieved by a Remain vote. Rather than turn our attention to progress, we���re wearing ourselves out trying to avoid regress.

Brexit distorts the policy agenda in other ways. For example, industrial policy should be concerned with increasing productivity and innovation. But in fact, it���s focused upon limiting the damage of Brexit, perhaps by offering handouts to favoured big firms whilst letting smaller ones swivel in the wind.

And then there���s the question of the values promoted by the Brexit debate. Brexit fuels nativism and even perhaps mercantilism, whilst the policies it squeezes out would focus instead upon more enlightened ideals such as liberty and equality.

All this, however, poses the question: is there really an opportunity cost here at all? Might there instead be an opportunity benefit?

All the above assumes that we are on a kind of policy production possibility frontier, so that Brexit means less good policies or administration elsewhere. But what if we are in fact well inside the frontier? Then Brexit ��� far from being a barrier to good policy elsewhere ��� might actually help it.

For example, had we not had Brexit Cameron and Osborne would still be in office so we���d be stuck with fiscal austerity. As it is, their departure has created space for a ���reset��� of policy. If Johnson and Fox were not tied up with Brexit negotiations, they���d probably find some ways to damage our polity. And a government whose energies and political capital weren���t sapped by Brexit might well have even more ability to hurt the worst off.

Which brings me to a paradox. We lefties can be quite relaxed about the opportunity cost of Brexit. Yes, Brexit is regrettable, but it has the silver lining of distracting the Tories from doing damage elsewhere. Tory supporters, however, have no such comfort. They should regard Brexit as a distraction of government energy which could be well-employed elsewhere. In this sense, it is intelligent Tories who should most regret Brexit.

Chris Dillow's Blog

- Chris Dillow's profile

- 2 followers