Chris Dillow's Blog, page 74

September 23, 2016

GBBO & the nature of the firm

Channel 4���s purchase of the Great British Bake Off raises big economic questions: what exactly is a firm, and what are a firms��� assets?

As you all know, Mary, Mel and Sue will not be joining the show when it moves channel, which has prompted everyone to claim that Channel 4 have spent ��75m on a tent and a fat scouser ��� something they could have got in Millets Liverpool���s branch for rather less.

This highlights a general fact ��� that firms are often not merely collections of physical assets, intellectual property and explicit contracts. Their value often lies in key employees, and if these leave they can take a lot of corporate value with them. If viewers boycott the new GBBO because there���s no Bezza, then the GBBO is indeed not as valuable as Channel 4 thought.

There���s nothing new in this. Back in 1994 shareholders in Saatchi and Saatchi got the hump with Maurice Saatchi and sacked him as chairman. He left to form a new advertising agency, taking a lot of Saatchi and Saatchi���s clients with him; the company never recovered. Shareholders thought they could control a valuable firm. But in fact a lot of the firm���s value was de facto controlled by Lord Saatchi. Channel 4 might have made the same mistake.

As Luigi Zingales pointed out in a classic paper (pdf), this changes how we should think about the firm. De facto decision rights ��� the things that give a company value beyond the value of explicit contracts - don���t necessarily lie at the top of the organization with shareholders, but might be scattered throughout the organization. This affects how companies can raise finance and how it should be valued: as Channel 4 might discover, it implies that assets can be less valuable than thought.

In truth, sensible people ��� the sort who aren���t TV executives ��� have known this all along. Private equity firms, among others, often devote lots of effort to retaining and incentivizing management at the companies it buys into: it���s odd that Channel 4 never thought of this. And one solution to the problem of powerful workers is to give them ownership, or the prospect thereof; law and accountancy firms, where people really are the main assets, are typically owned by worker-partners and not by outside shareholders.

So far, so obvious. But here���s a problem. Sometimes, we don���t know where power lies. Is the GBBO like Top Gear which slumped when Jeremy Clarkson left? Or is it like the One Show or The Voice, which coped well with changes of judges and presenters? (Taggart even kept going long after the death of the actor playing the title role). The fact is, we can���t be sure. Of course, TV presenters and key employees in many firms like to think they are vital to the enterprises��� success. But the graveyards are full of men who thought they were indispensable.

This suggests that the valuation of many smaller companies, or parts thereof, might be even more uncertain than thought.

Warren Buffett has his own solution to this uncertainty ��� to invest only in companies which are so structurally sound as to be not dependent upon particular individuals:

If you've got a good enough business, if you have a monopoly newspaper, if you have a network television station ��� I'm talking of the past ��� you know, your idiot nephew could run it. And if you've got a really good business, it doesn't make any difference.

Sometimes, though, you cannot avoid the uncertainty. And then you have a problem, as Channel 4 might discover.

September 22, 2016

The centrist crisis

Tim Farron said this week that ���there is a hole in the centre of British politics right now.��� This is true, if not in the sense he intends.

What I mean is that several big political developments of recent years are a backlash against centrist politics: the rise of Corbyn; Brexit; the collapse in the LibDems vote in 2015; growing distrust of experts; and increasing hostility to immigration. The hole in centre exists because voters have deserted it. Such trends, of course, have counterparts in the US and much of Europe.

There���s a reason for this. Centrism requires a healthy capitalism. Support for a mixed economy rests upon the ability of capitalism to raise living standards and generate the taxes that pay for public services. And the centre ground requires that people have a stake in the system (so they don���t want radical change) but also have trust in the Establishment and goodwill towards others, so they support mildly progressive policies. This too depends upon capitalism being healthy ��� because as Ben Friedman has shown, good economic growth creates tolerance, trust and open-mindedness whist stagnation breed intolerance and extremism.

But this economic base for centrism has greatly weakened. As the IFS says, real median earnings are still lower now than they were before the crisis. As a result, older workers��� incomes haven���t changed since then whilst younger ones��� have fallen significantly.

On top of this, unaffordable housing means that younger people have less stake in the economy than they used to have, whilst job polarization and the degradation of formerly middle-class jobs have undermined the sense of content with the system which has often been the bedrock of centrism.

We saw in the 1930s and 70s that economic crises weaken the political centre. We���re seeing that again.

However, centrists haven���t just been hurt by the economic crisis. They are also in intellectual disarray, which might in part be the result of their failure to adapt to the stagnation of capitalism. Yesterday, thehistorian said that Labour���s centrists ���don't have enough alternative ideas���. Bang on cue, David Miliband���s piece in the New Statesman vindicates him. Whilst David is absolutely right to say that secular stagnation and turbocapitalism pose new challenges for the centre left, he is sadly silent on what policies might meet these challenges.

Anti-centrists do have answers here. Nativists say closed borders; the libertarian right says freer markets; and the Left says higher corporate taxes, nationalization and printing money. Such answers might be inadequate or worse. But something beats nothing. And nothing is what the centrists seem to have.

This, however, need not be the case. Support for tax credits, infrastructure spending, more choice and voice in public services, the softest of Brexits (if any) and better early years education are good coherent policies which the centre could offer*.

And there���s one big cognitive bias which centrists could exploit. This is the compromise effect ��� the tendency of people to choose middling options when faced with extremes. Voters have often backed centrist parties for the same reason they buy the second-cheapest bottle of wine rather than the cheapest or middlingly-priced TVs rather than high-end ones. If the centre could find a viable proposition, and sell it by exploiting the contrast to the extremes, it might have a future.

Or would it? Whilst the intellectual crisis of centrism is resolvable, the economic stagnation that has caused a revulsion with the centre might not be.

* Personally, I doubt that they���d be adequate ��� but they���re better than nothing.

September 21, 2016

Persuasion in a post-truth world

How should economists engage with a man who knows nothing about economics? Matthew Bishop says we should treat him as a ���worthy interlocutor in a way that values his opinion���. I���d caveat this.

We should make two distinctions here. One is between the man who genuinely wants to learn more, and the one who is loudly spouting nonsense for political reasons.

The former deserves all our help. Geoff Riley and Diane Coyle offer useful suggestions for him, but I fear that there aren���t ways of supporting such people; the media generally fails atrociously.

The latter, however, deserves our derision and contempt ��� of the sort that Douglas Carswell got when he claimed that the sun rather than the moon causes tides*. Such people are polluting public debate, and generally committing several cognitive biases as well: overconfidence; the halo effect (the belief that a policy that���s good in one aspect must be good in others); motivated reasoning; and the Dunning-Kruger effect too.

In this context, I���m not sure about Matthew���s analogy:

If physicists laughed at everyone who attempted to comprehend what is happening at CERN, or linguists mocked every grammatical error made by friends practising their holiday Spanish, people would soon give up trying to participate out of exhaustion.

This would be a bad thing if people were genuinely trying to understand and get better. Many, though, are just closed-minded bigots. One of the most deplorable trends of our time is the rise of narcissistic loudmouths and the media���s encouragement of them. Such people should be told: shut up you ignorant lout**.

Here, though, lies my second distinction: between what is practical and what is ethical. Just because a man deserves our contempt does not mean it is practical to give it him. Matthew is right to say that if we are to change his mind, we should meet him halfway ��� by taking whatever sliver of truth there is in his beliefs and using it to enlighten him. As Blaise Pascal said:

People are generally better persuaded by the reasons which they have themselves discovered than by those which have come into the mind of others.

There is, however, a danger here. In taking mistaken ideas seriously, we risk giving them more credence than they merit. And persuasion might be more practical if it exploits cognitive biases than if it tries to overtly oppose them. On both counts, we might face a trade-off between truth and effectiveness, which risks us forgetting Galileo���s words: ���e pur si muove���.

The issue here is, of course wider and deeper than merely how economists engage with the public: I suspect the same issues arise in science and other areas of policy.

The underlying problem here is: how should we cope with the death of liberal optimism? Advocates of free speech such as John Stuart Mill believed that ���wrong opinions and practices gradually yield to fact and argument���. In a post-truth world of asymmetric Bayesianism where people have had enough of experts such confidence is unwarranted. Liberals and experts have so far failed to come to terms with this.

* This just shows that we should leave the solar system to stop foreign bodies meddling with our seas. Let���s take back control of our tides.

** I try to do this: there are huge numbers of subjects - including a lot of economics - about which I know little: I try to keep quiet about them.

September 20, 2016

In defence of technology shocks

In his attack (pdf) upon macroeconomic theory, Paul Romer is especially critical of the real business cycle view that recessions are caused by negative technology shocks. He calls them ���phlogiston shocks��� and says:

there is no microeconomic evidence for the negative phlogiston shocks that the model invokes nor any sensible theoretical interpretation of what a negative phlogiston shock would mean.

Simon accuses him of attacking a straw man, saying that ���the insistence on productivity shocks as business cycle drivers is pretty dated.��� And the standard undergraduate textbook, Carlin and Soskice���s Macroeconomics, says RBC theory ���is not the mainstream view.���

Looking through a macro prism, such scepticism is reasonable. How can people forget how to do things? Yes, there can be intellectual regress (which is what Romer alleges of DSGE models!) but surely not at the frequency of business cycles.

However, if we ditch representative agent thinking and think instead of firms as being inherently heterogenous, the notion of a negative technology shock seems more reasonable.

Xavier Gabaix points out that even in a large economy aggregate fluctuations can arise from the failure of one or two big firms. This is especially possible if those firms are important hubs, whose troubles plunge supplier or customer firms into trouble: as Daron Acemoglu shows, networks are crucial in transmitting (or dampening) firm-level shocks throughout the economy.

It seems to me that this is a plausible description of the financial crisis. Banks became less able to supply credit than we thought; this was a firm- or industry-level negative technology shock. And because banks were key hubs, this shock was transmitted to the wider economy.

You can squeeze this into DSGE-style models, as (for example) Michael Wickens (pdf) and Hashem Pesaran (pdf) have done. Whether you should do so, though, is another matter: I fear that such exercises might be examples of economists seeing something happening in the real world and wondering if it is possible in theory.

However, evidence on the importance of firm-level shocks is not confined to 2008-09. In Coping with Recession Paul Geroski and Paul Gregg estimate that just 10% of firms accounted for 85% of the drop in employment in the 1989-91 recession. It���s not clear whether this was due to an identifiable single technology shock or what. But this is strong evidence that heterogeneity matters. They wrote:

Describing what happens during recessions using simple macroeconomic aggregates and representative firm models of the economy produces a seriously distorted picture of events. Recessions are about what happens to differences between firms much more than they are about what happens to firms on average.

Now, I���m not saying here that recessions are always and everywhere technological phenomena; recessions differ and maybe there���s no single general theory of what causes them. Nor does this view necessarily have policy implications. One could argue that whatever causes recessions, the response should be expansionary macro policy.

There might, however, be one implication of this. If recessions are occasionally due to technology shocks, then they might be sometimes be inevitable and unpreventable by macro policy: the consistent failure of economists to forecast recessions is consistent with this (though not proof of it).

What I���m doing here is making a plea. In throwing out the bathwater of representative agents and the very dirty bathwater of equilibrium business cycles, economists should be careful to keep the baby of possible technology shocks.

September 19, 2016

Immigration as social mobility

Last week, Theresa May spoke of wanting to increase social mobility, so that ���it���s your talent and hard work that matter, not where you were born.��� This week she wants to restrict immigration. There���s a massive contradiction here.

I say this for a trivially obvious reason ��� that migration is a fantastic form of social mobility because it raises people out of poverty. Orley Ashenfelter, for example, shows (pdf) that real wages at McDonalds are seven times higher in the US than in India: Indians are poorer than westerners not because they���re less talented or lazier but because India is a poorer country.

Allowing people to migrate would allow them ���to go as far as their talents will take them���, which is what Ms May wants. Immigration controls, on the other hand, mean that ���where you were born��� will, in millions of cases, condemn you to life-long poverty.

It���s obvious, therefore, that anyone who is sincere about wanting everyone to have a ���fair chance to go as far as their talent and their hard work will allow��� should favour open borders.

So, why doesn���t Ms May?

One possibility is that she simply hasn't thought about it much - though what does that tell us about politics?

There are some nastier possibilities. Maybe she doesn���t want real meritocracy but merely a sham appearance thereof that would serve to legitimize inequality.

Worse still, it might be because of the same sort of hypocrisy that leads Europeans to want rights of free movement for themselves but not for others. Whereas we British have ���legitimate concerns��� that politicians must address, foreigners are a problem to be managed. Chris Bertram say this is racist. I���d add that it looks like feudalism: the highborn (those of us born into rich countries) have a right to preserve and increase our wealth, whereas the lowborn must be kept in poverty by the use of force.

Maybe I���m being too harsh here, though. Perhaps the free migration that would increase social mobility would incur some costs ��� not so much economic as cultural or just the sort of sense of disquiet that accompanies rapid change. And perhaps members of nations have obligations to each other that justify excluding outsiders, even though these nations are in part merely imagined communities: this is one issue in the debate (pdf) between the Rawls of The Law of Peoples (pdf) and cosmopolitans.

I don���t want to take sides on this: FWIW my instincts are for open borders but I see that this would have huge practical problems. My point is merely that immigration restrictions are a massive barrier to social mobility, meritocracy and the alleviation of absolute poverty, and should therefore be supported if at all only with a heavy heart and misgivings about their massive cost. What I find hard to understand or forgive is that so few of their advocates seem to feel such misgivings.

Another thing: you might object that politicians have a duty to their voters, not to the world. This is too glib: can people really legitimately incur duties to harm others? Should we, for example, respect a hired killer's duty to carry out his employers' orders?

September 16, 2016

Grammar schools & stereotype threat

In the debate about grammar schools, everybody assumes that it is those who pass the 11+ who should be admitted to them. But why should this be? Mightn���t it be more efficient instead to admit those who do badly?

I ask because of some recent experiments by Victor Gonzales at Tilburg University. He got people to solve some Raven���s matrices. Then he randomly gave out medals and asked people to redo the tests. He found that low-ability people who got a medal improved substantially, whilst high-ability people who didn���t get one did just as well.

The reason for this lies in self-serving biases. Low ability people who got a prize thought they were good and this increased their ambition and self-belief, thus motivating them to do better. As Arsene Wenger said, ���If you do not believe you can do it then you have no chance at all���. However, high ability people disregarded the signal sent by the lack of a prize, believing they were good anyway.

I know, I know. At this stage many of you are shouting: this looks like the sort of priming result that is notoriously hard (pdf) to replicate.

However, I suspect it does have real-world relevance. Stereotype threat ��� our tendency to live up or down to stereotypes ��� is a real thing. As Rachel Kranton has shown, our (self)-identity shapes our behaviour, and this identity isn���t wholly exogenous but is at least in part shaped by our environment and by how others perceive us.

For example, girls in mixed schools are less likely to choose to study ���masculine��� subjects such as maths and science because being surrounding by boys reminds them more of their femininity and so prompts them to act girly. Jeffrey Butler has found that inequality leads to unwarranted perceptions of one���s ability. And Robert Oxoby has shown that low expectations ��� such as those formed by growing up in poverty ��� can reduce people���s ambitions and make them satisfied with less. People really can end up like a dog that���s been beat too much.

You might think this is a case for admitting 11+ failures into grammar schools. Low ability kids who get the prize of a place will raise their performance, whilst high-ability kids who fail won���t do worse: think of Will MacKenzie or Adrian Mole at their sink schools believing they were better than the rabble. Overall, academic performance will improve.

However, I don���t think this inference is warranted. This will only work if the low-ability kids are deceived into thinking they are good. This is probably not a trick that can be pulled off for long.

Perhaps a stronger inference would be that grammar schools are a bad idea because there���s danger that stigmatizing some people as being of low ability might prove to be self-fulfilling.

September 15, 2016

An academic problem?

Some mainstream economists have recently attacked DSGE models. Olivier Blanchard says (pdf) there are ���many reasons to dislike��� them. And Paul Romer says (pdf) they���ve caused ���intellectual regress��� into a ���post real��� doctrine which attributes economic fluctuations to imaginary causes.

I want to ask a question which is implicit in Romer���s paper: is the problem here (assuming it be such) specifically with economists, or rather with academia in general?

I ask for three reasons.

First, macroeconomic analysis outside universities does not use DSGE models. Neither economic writers nor investment bank economists use them: they might often be wrong, but not I suspect because of this. And the role such models play in central banking is mixed. Yes, the Bank of England has one, but the Fed���s main model isn���t a DSGE one. And I���m not sure how far DSGE models influence policy-making. Month-to-month policy changes rely more upon judgement and interpretation of high-frequency data than pure modelling. And the main policy innovation of recent years ��� QE ��� didn���t emerge from DSGE thinking. As Ben Bernanke said, ���The problem with QE is it works in practice, but it doesn���t work in theory.���

Secondly, Romer says there are ���striking parallels��� between what he calls ���post-real macroeconomists��� and string theorists in physics: groupthink and a tendency to interpret evidence optimistically. This suggests there might be a problem common to some academics rather than just economists.

Thirdly, whenever we see intelligent people doing things that look silly, we must ask the economists��� questions: what are the incentives and constraints here? Might it be that incentives in academia sometimes generate a bias towards the habits Romer deplores? For example, whilst peer review helps maintain high standards it might also encourage fashion and groupthink: methods and results that please referees are the way to get published. This generates an incentive to do what Kuhn called normal science rather than work that challenges the paradigm. And perhaps a little distance from the ���real world��� leads to excessive weight upon theoretical elegance and too much tolerance of reliance upon unobservables.

Now, I stress that I���m only posing a question here. I���m not rubbishing academic economics in general. For every Thomas Sargent or Robert Lucas there���s a Wendy Carlin and Simon Wren-Lewis. And as Noah has said, many fields of economics have become more empirical in recent years - though some doubt whether this will reap the hoped-for fruits. I���m merely asking a conventional question in economics: do incentives occasionally have perverse effects? As Jon Elster said, mechanisms are sometimes switched on and sometimes off.

Nor am I arguing that universities must change, except perhaps that they should, as Blanchard says, embody more cognitive diversity ; the idea of them becoming even more corporatized appalls me. Perhaps my point is just that all institutions are necessarily imperfect that that all professions are subject to their own biases, and that occasionally the two might combine to ill effect.

September 14, 2016

The dying bird of globalization

Tom Paine famously said of Edmund Burke that he ���pities the plumage but forgets the dying bird.��� This accusation applies to many free marketers.

I���m prompted to say this by a post from Simon Cooke. He argues against nativist anti-free traders of left and right that:

Trade - free exchange between individuals - is mutually beneficial. It's not a competition between nations, it's not a 'global race', and it's not a winner-take-all game of international treaty poker. The whole bloody point is that both participants gain.

I largely agree. But Simon is making mistake here common to many free marketers. He���s overstating the threat to free markets that come from politics, and understating the extent to which they come from actually-existing capitalism itself. He's forgetting that capitalism looks like a dying bird that is no longer laying the eggs of freer trade.

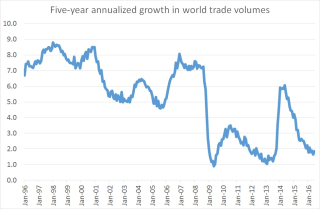

My chart, taken from CPB data, shows what I mean: Martin Wolf provides other evidence. It shows that growth in world trade has slowed sharply since the 1990s and early 00s. This has nothing to do with nativists like Trump, Le Pen and Brexiters. It���s because of factors largely endogenous to capitalism.

There are several such factors here; as with the productivity puzzle (which might well be related to the trade slowdown) the precise answers are unclear. Among them are:

- The fast growth in trade in the 90s and 00s was due in part to one-off factors that have faded ��� such as the reintegration of China and former Soviet bloc economies into the global economy and the reaching of easier free trade deals.

- The migration of low-wage work to Asia has slowed, in part because rising wages there have reduced their cost advantage.

- Since the financial crisis firms have feared that even if credit is available now it might not remain so in the next crisis. This has reduced trade, as this is dependent upon finance.

- Companies have learned that long and complex supply chains are hard to manage, with the result that some have begun to re-shore.

I���d add to this that support for anti-globalization policies (such as tougher immigration controls as well as trade restrictions) are also endogenous to capitalism. They arise from the fact that many people in the west feel that capitalism is failing them ��� and they are drawing an incorrect conclusion from a reasonable premise.

Whatever the reason, the fact is that, as Michael Roberts says, globalization has ���ground to a halt.��� Granted, this might change: we���ve seen globalization falter and recover in history. But it might not, at least soon.

My point is, though, that the threats to free trade and the prosperity it brings don���t come merely from silly people believing silly things. They are more profound than that.

September 13, 2016

"Rather good at it"

Phil reminds us of the answer David Cameron once gave to the question, why do you want to be Prime Minister? ���Because I think I���d be rather good at it.���

Well, that didn���t work out too well did it? We���ve had plenty of PMs whose policies we didn���t like. But Cameron was, as Owen Jones says, ���a failure on his own terms���. He wanted to eliminate the government deficit and keep us in the EU, and failed on both. I���d add that this his counter-productive pursuit of austerity contributed ��� at the margin ��� to Brexit by creating a climate of insecurity and xenophobia. In this sense, Cameron���s failure was down to deliberate ineptness rather than to facing insuperable odds. For this reason, he is probably one of our worst-ever Prime Ministers.

This poses the question: what, then, was the basis of his belief that he���d be ���rather good��� at the job?

It���s not that he had a great grasp of economics or politics. His mindless drivel about a ���global race��� and the ���nation���s credit card revealed utter ignorance of the former. And I���ve long said that Cameron���s government failed to grasp the nature of politics ��� that it consists in ameliorating problems of collective action.

Instead, his confidence was rooted not in facts but in class. It���s a clich�� that going to a top public school often gives one confidence and arrogance which others lack. Here���s Jimmy McGovern (16���20��� in):

Particularly in the working class north, the one thing you do not want is arrogance���so the slightest sign of arrogance in your child you knock it out of them. But in knocking out the arrogance you knock out the ambition, the self-respect, the self-esteem.

So much is obvious. But this poses a question. We are all cognitively flawed. Only some such flaws, however, are penalized. Public school overconfidence, however, seems to be actively selected for: 19 of our 54 PMs went to Eton, and public schoolboys are over-represented in most professions. What are the mechanisms that allow such irrationality to thrive? Here are a few, in no order.

First, there are competence cues. Cameron Anderson and Sebastien Brion show that overconfident people give out more ���competence cues��� ��� such as fluency and body language ��� than others and that these cues are mistaken for actual ability, with the result that the overconfident are more likely to get jobs, regardless of ability. This might have been true of Cameron: in 2005 ConservativeHome said his leadership campaign was ���transformed��� by ���two compelling performances��� ��� exercises in fluency and confidence.

The converse of this is that the under-confident but able don���t apply for jobs in the first place: this might mean there���s a case for positive discrimination or quotas.

Secondly, there are overconfidence bubbles. Once you���ve gotten a job through no merit of your own then your overconfidence will tend to grow, perhaps causing you to become dizzy with success and so making a fatal error. We know this happens in financial markets: lucky traders take more risk. It might well have happened with Cameron: his success at winning the Scottish independence referendum made him think he could repeat the trick with Brexit.

A third factor is deference. I���m not thinking here merely of underlings deferring to bosses out of self-interest, but to a tendency identified by Adam Smith:

We frequently see the respectful attentions of the world more strongly directed towards the rich and the great, than towards the wise and the virtuous. We see frequently the vices and follies of the powerful much less despised than the poverty and weakness of the innocent. (Theory of Moral Sentiments,I.III.29)

Contrast, for example, the way the media indulged ���Boris��� with its othering of, say, John Prescott.

A further selection effect is the desire to overcome agency problems. It���s natural for hirers to want people they can trust, and we trust people like ourselves. Public schoolboys will therefore hire public schoolboys, even if they have no deliberate nepotistic intentions. This can lead (pdf) to a lack of cognitive diversity and to groupthink and the Dilbert principle.

My point here is that selection mechanisms ��� in politics and in markets ��� don���t necessarily weed out irrationality. Quite the opposite. They sometimes select for it. It is these mechanisms that must be dismantled. In this sense, if we are to be better governed in politics and business, we need more class war.

September 11, 2016

"Fat and lazy"

I welcome Liam Fox���s claim that many British bosses are too ���fat and lazy��� to increase exports.

For one thing, it���s a good corrective to the ideology ��� too often promoted by the BBC ��� that bosses are infallible heroes to whom we owe deference and big pay-packets.

And for another, it contains some truth ��� and not just in the sense that businessmen are less assiduous in chasing a pound than Dr Fox. Most UK firms ��� more than 90% - don���t export at all. And the UK exports less as a share of GDP than comparable economies such as Italy, France or Germany (As a rule, smaller economies have higher export-GDP ratios that bigger ones.) This shouldn���t surprise us. In the real world, competition doesn���t grind so finely that it swiftly eliminates mediocrity, incompetence and laziness.

But here���s the thing. For many of us the fact that some businesses are ���fat and lazy��� was a key reason to favour remaining within the EU. When Brexiters told us that Brexit would allow us to reach free trade agreements with non-EU nations, our response was a fear that exporters would not quickly or sufficiently step up sales to non-EU countries. You can think of ���fat and lazy��� as micro-foundations for the gravity models of trade which underpinned the economic case (pdf) for Remain.

Which poses the question: what, then, is Fox doing?

I suspect it's another example of the (self?)-deception of Brexiters. He���s getting his excuses in early. If Brexit is followed by faltering exports, Fox will say it���s because businesses are too fat and lazy to take advantage of the opportunities he has created.

In this sense, what we���re seeing is an old trick of ideologues ��� that when your ideas fail, it is the fault not of their inadequacies but of the failure of reality to conform to the visions in your head.

Chris Dillow's Blog

- Chris Dillow's profile

- 2 followers