Chris Dillow's Blog, page 73

October 8, 2016

When to distrust elites

Whom should we trust: elites or the people? I���m in two minds here.

On the one hand, on the issues of immigration and Brexit, I���m with the elites.

But in other respects, I���m on the side of the people. I���ve repeatedly argued for worker democracy against managerialism, and have consistently pointed out the shortcomings of professional fund managers. And I���ve pointed out that popular opinion ��� as measured by ratios (pdf) of consumer spending to asset prices ��� can do a better job of forecasting future economic conditions than professional forecasters can manage.

So, am I just confused?

No. There���s a logic to my position which is lacking in extreme pro- or anti-elitism. To see it, remember that crowds are wise only under specific conditions. These are:

- Beliefs are uncorrelated, so there���s no herding or information cascades.

- There���s a diversity of belief, with people drawing on their personal and perhaps tacit knowledge of local circumstances.

- People have incentives to get the decision right.

I side with the people when these conditions are in place. This is true of the ability of consumption-wealth ratios to predict future economic conditions. This works because each individual decides his spending according to personal circumstances: is my job safe? Will I get a decent bonus? Do I have good prospects? And so on. And everyone has an incentive to get the decision right: spending too little means unnecessarily depriving yourself whilst spending too much means uncomfortable retrenchment later. Granted, it���s possible for spending decisions to be influenced by peer pressure. But I suspect this mechanism is often not powerful enough to offset the strength of the other conditions.

I suspect too that these conditions would often facilitate worker democracy. Each worker has local specific information about how the firm might increase efficiency, and has skin the game (job-specific human capital) that incentivizes him to express a good opinion.

However, in the case of Brexit, these conditions are absent. Voters��� beliefs are correlated, by virtue of being unduly influenced by the shit media (including the BBC) as well as by cognitive biases. There���s little local, fragmentary knowledge to be aggregated: not many voters were swayed by their personal experiences of dealing with the EU. And they didn���t have skin in the game: many older voters believed, sadly correctly, that the costs of Brexit would be borne by others.

Herein lies the paradox. Although there exist good criteria for adjudicating when we should trust the people and when the elites, I seem to be the only one who applies these criteria. Instead, popular opinion distrusts elites when they should be believed ��� for example on Brexit ��� and yet believes them when they should be distrusted: there���s insufficient demand for worker democracy, and far too much trust still placed in fund managers.

What we���re seeing, therefore, in today���s populism is the exact opposite of what intelligent, evidence-based class war should be.

October 7, 2016

Socializing investment

Philip Hammond promised this week ���to renew and expand Britain���s infrastructure���. This might represent a return to Keynesianism in more ways than one.

The obvious sense is that he���ll be using fiscal policy counter-cyclically, supporting the economy during a time of Brexit-induced uncertainty; economists expect real GDP growth of only 0.7 per cent next year, well below long-term averages.

But there���s another sense. Keynes also looked forward to ���a somewhat comprehensive socialisation of investment.��� Hammond might push us in this direction.

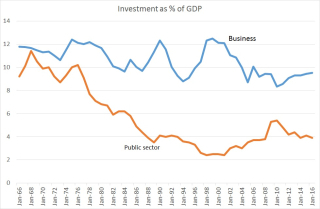

My chart, taken from ONS and OBR data, puts this into historical context. It compares business investment to public sector investment. You can see that in the early 70s the two were similar. Then during the 1979-97 Tory government public sector investment declined markedly. From the late 90s until 2010 however the gap between public and business investment narrowed, until Osborne���s austerity and a pick-up in business investment widened the gap again.

It���s possible that the next few years will see a resocialization of investment, to the extent that Hammond raises public sector investment at a time when Brexit uncertainty, as well as secular stagnation, holds down private sector investment.

In truth, though, there���s another force which might resocialize investment ��� relative prices. Infrastructure spending is prone to an element of Baumol���s cost disease. Because construction tends to have relatively slow labour productivity growth, its relative cost rises over time. However, to the extent that business investment comprises spending on IT, it benefits from Moore���s law and so sees a fall in relative prices. These trends alone would tend to raise the share of public investment in GDP over time, and depress that of business investment: my chart shows ratios of investment to GDP in current prices.

And herein lies a problem. It���s widely agreed that better infrastructure would raise productivity: better roads and broadband would make us more efficient. But there���s a downside here. A greater share of infrastructure spending in GDP, and smaller share of business investment, would tend to depress productivity growth because of brute maths ��� because a sector with low productivity growth accounts for a bigger share of GDP.

I like to think that the former effect will prevail ��� and it probably will initially. Over the very long-run, however, this might be more doubtful.

October 6, 2016

The democracy problem

If a man asks for a lot of rotting fish, should we blame the fishmonger for giving it him? I���m prompted to ask by David Aaronovitch���s piece in the Times attacking the Tories��� anti-immigration rhetoric.

The objection to David���s argument, of course, is that the government is giving the public what it wants. It wants stinking fish.

Of course, in saying this I sound like the sort of elitist May sneered at yesterday. Nevertheless, people like David and I have a real problem that, in truth, dates back centuries: how can we reconcile democracy with good government?

One answer, advanced recently by Jason Brennan, is that we can���t. He says:

Most voters are ignorant of both basic political facts and the background social scientific theories needed to evaluate the facts. They process what little information they have in highly biased and irrational ways. They decided largely on whim. And, worse, we���re each stuck having to put up with the group���s decision. Unless you���re one of the lucky few who has the right and means to emigrate, you���re forced to accept your democracy���s poorly chosen decisions.

He advocates epistocracy, in which ���political power is to some degree apportioned according to knowledge.���

That���s ��� ahem ��� brave. Historically, we���ve used other ways of reconciling democracy and good government. One way has been to preface democracy with ���liberal���, so that people���s rights act like ���trumps��� to over-ride the tyranny of the majority. Another way was proposed by Edmund Burke ��� yes, the same Burke that May praised in her speech yesterday. He said MPs should use deliberative judgment rather than act as mere delegates enforcing the popular will:

Your representative owes you, not his industry only, but his judgment; and he betrays, instead of serving you, if he sacrifices it to your opinion��� parliament is a deliberative assembly of one nation, with one interest, that of the whole; where, not local purposes, not local prejudices, ought to guide, but the general good, resulting from the general reason of the whole. You choose a member indeed; but when you have chosen him, he is not member of Bristol, but he is a member of parliament. If the local constituent should have an interest, or should form an hasty opinion, evidently opposite to the real good of the rest of the community, the member for that place ought to be as far, as any other, from any endeavour to give it effect.

Proposals for deliberative democracy such as those from Archon Fung and Joel Rogers among others are attempts to revive this ideal.

Herein, though, lies a paradox. On the one hand, the need to explore these various ways of cleansing voters��� preferences has become more pressing in recent years not just because of the rise of racism ��� let���s call it what it is ��� but because we have ever-growing evidence that people have limited rationality, knowledge and attention. I���m not sure if Jason Brennan, Bryan Caplan (pdf), Daniel Kahneman, Dan Ariely and me would agree upon much, but we agree on this.

On the other hand, though, we���ve also seen a rise in a crude consumer sovereignty view of politics in which the voter is king whose preferences must be respected and whose ���legitimate concerns��� must be heeded.

It���s this latter view which must be challenged. We must ask: can we change voters��� minds? How can we reconcile democracy with better government? Partisan attacks on the Tories��� brutal and economically illiterate anti-immigration attitudes are right and necessary, but they deflect attention from much deeper questions.

October 5, 2016

May's challenge to Marxism

Theresa May���s government poses a challenge to us Marxists.

What I mean is that Marx and Engels saw the state as a means of promoting capitalists��� interests. It is, said Engels, "the instrument for exploiting wage-labour by capital".

However, this government seems not to be acting in capital���s interests. Its desire for tougher immigration controls is opposed by both the CBI and British Chambers of Commerce; even the FT calls the government ���jackbooted overlords���. And the pursuit of a hard Brexit is generating uncertainty and jeopardizing the City���s future business.

Given this, how can we Marxists claim ��� as the Communist Manifesto did ��� that ���the executive of the modern state is but a committee for managing the common affairs of the whole bourgeoisie���?

There are two answers here.

First, we should distinguish between the policies of any particular government and the basic structure of the state. It���s plausible that the latter serves capitalists��� interests. For example, intellectual property laws protect monopoly power; banks get an implicit subsidy because of the prospect of being bailed out in bad times; government procurement and the Private Finance Initiative serve as forms of corporate welfare*; schools act as ideological state apparatuses indoctrinating students to act in capital���s interests; and the welfare state helps reduce business uncertainty whilst work assessment schemes ensure a high supply of labour. And so on.

Secondly, the state doesn���t always slavishly follow the requirements of capital. Engels went on to say:

Exceptional periods, however, occur when the warring classes are so nearly equal in forces that the state power, as apparent mediator, acquires for the moment a certain independence in relation to both.

This inspired Ralph Miliband���s theory of the relative autonomy of the state:

[State] power has often been used for purposes and policies which were not only pursued without reference to the capitalist class, but also at times against the wishes of many parts of that class, or even the whole of it���The state does not, normally and of its own volition, intervene in class struggle on the side of labour. But this does not mean that it is necessarily subservient to the purposes and strategies of capital. It is in fact often compelled, by virtue of its concern for the defence and stability of the social order, to seek some intermediate position, and to act upon it, however much that position may differ from the position of capital. (Divided Societies, p 31-32).

This is what we���re seeing now. Capital is relatively weak which has given the state an unusual degree of autonomy. Capitalism���s failure to deliver rising living standards (a process exacerbated by Osborne���s austerity) has generated a nationalist backlash which May feels compelled to accommodate even at a cost to business.

In this sense, May���s policies aren���t a refutation of a Marxian theory of the state after all.

But this poses a question. Mightn���t the notion of relative autonomy serve as what Popper called an ���immunizing strategy��� ��� a way of protecting Marx���s theory of the state from any possible refutation? If so, what would refute that theory?

Simple. If the state were to maximize labour���s bargaining power at the expense of capital ��� for example via a high citizens income, jobs guarantee and promotion of worker coops ��� it would cease to be ���a committee for managing the common affairs of the whole bourgeoisie���. Until this happens, however, Marx���s theory of the state looks reasonably valid.

* Yes, estimates of the size of the corporate welfare state are flawed, but this doesn���t change the fact that big government does help capitalists, which is why so few capitalists are libertarians.

October 4, 2016

Footsie's verdict on Brexit

One of the most egregious of cognitive biases is the confirmation bias - our tendency to see what we want. We���re seeing examples of this today, with Brexiteers cheering FTSE���s rise whilst Remainers point to sterling���s fall.

In truth, these are two sides of the same coin. One reason why the Footsie has risen might well be that sterling���s fall is expected to be permanent, and so will raise overseas earnings ��� which account for around three-quarters of the FTSE 100���s total earnings. It���s no accident that today���s biggest risers include a lot of overseas earners, such as Pearson, Standard Chartered and Royal Dutch.

We can put this in more sophisticated terms. Uncovered return parity (pdf) tells us that, in the absence of shocks, equity returns should be equalized across countries so that a relatively strong stock market should be accompanied by a weaker currency and vice versa.

But of course, that phrase ���in the absence of shocks��� is doing a lot of work. If a country were to enjoy a positive growth shock, its stock market should rise relative to others in common currency terms. This is because investors would buy the equities in the hope of rising dividends, and perhaps the currency too in anticipation of higher interest rates as a consequence of that faster growth.

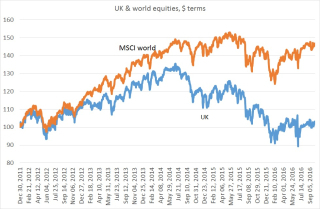

So, is this what the UK has enjoyed? No. Quite the opposite. Since June 23, MSCI���s index of UK stocks has fallen by 3.3 per cent in US dollar terms* whilst the MSCI world index has risen 2.7 per cent.

This underperformance of six per cent is consistent with the sort of long-term hit to GDP which NIESR and the CEP (pdf) expect from Brexit. Is that a coincidence?

Granted, Brexiteers are right to say that the lower pound will stimulate exports and output. But Remainers are also right to say that the pound has fallen precisely because investors expect weaker growth as a result of Brexit: it���s fall in the last few days might well be due to the perceived increased prospect of a ���hard Brexit���.

The fact that UK equities have under-performed in common currency terms since June 23 tells us that the stock market believes that, on balance, the latter effect outweighs the former. This is consistent with empirical evidence which tells us that past falls in sterling haven���t had a huge impact on net exports**.

If stock markets are saying anything, it is that they agree with mainstream economists that Brexit will harm the UK.

Let���s put this in context, though. The UK���s underperformance since June is actually quite small in the context of its under-performance since mid-2014. That���s due in part to the UK���s bigger weighting in mining stocks. But it might also be because expectations for relative growth were falling even before this June: small caps and the FTSE 250 are well down in dollar terms since mid-2014.

I must, however, caveat all this massively. Drawing strong inferences from noisy and complex phenomena is dangerous, and downright daft when those inferences are politically motivated. And paying attention to short-term market fluctuations is almost to invite error ��� in particular, the mistake of myopic (pdf) loss aversion (pdf). Charles Kindleberger used to say that ���Anyone who spends too much time thinking about international money goes mad.��� The same applies to stock market moves.

* I���ve updated this to include today���s rise in UK shares and fall in sterling.

** Yes, the UK economy did nicely after we left the ERM in 1992. But this was probably due more to the monetary and fiscal easing than to the pure exchange rate effect.

October 1, 2016

Generational vs class divides

In a typically great post, Rick challenges the notion that people born between the mid-40s and mid-60s represent some kind of homogenous generation. I agree, and want to amplify his post in two ways.

First, one reason why there���s a massive difference between those born in the mid-40s and those in the mid-60s is that our formative years were very different. The mid-40s generation left school in the early 60s, a time of full employment when even the unqualified could walk into albeit unsatisfying work. My generation left school at a time of high and rising unemployment. This is the difference between Arthur Seaton and Damon Grant*.

In the early 80s, a typical domestic scene in declining industrial areas between my friends and contemporaries and their dads went as follows:

Dad: Get a job.

Son: What as ��� a unicorn farmer?

Dad: There are jobs if you���re willing to look.

Son: No there aren���t.

Exchange of Effing and Jeffing. Son storms out, to see his grandad who, having grown up in the 1930s, gives him a sympathetic hearing.

Shared formative experiences matter more than temporal closeness; there was/is therefore a big difference between the mid-40s and mid/late 60s generations.

Academic research backs this up. A recent paper by Nathanael Vellekoop finds:

The more aggregate unemployment an individual has experienced during his or her lifetime, the lower the score on agreeableness, emotional stability, extraversion and openness.

This corroborates work (pdf) by Ulrike Malmendier and Stefan Nagel who have found that growing up in hard times makes people risk averse even decades later, and Henrik Cronqvist who has found that:

Investors with adverse macroeconomic experiences (e.g., growing up during the Great Depression or entering the labor market during an economic recession) or who grow up in a lower socioeconomic status rearing environment have a stronger value orientation several decades later.

There���s a common theme here. Recessions make us distrustful; we prefer the pound on the table to the promise of two down the road. Rick is bang right to highlight the massive gulf between hippies and my generation who have plain contempt for ���all you need is love��� drivel*. This gap is based upon diametrically opposite economic experiences.

But there���s something else. When Rick says that we 60s-born generation face a harder and shorter retirement than those born in the 40s, he���s describing a difference between averages. But of course averages conceal big variations. Some of us are considering retirement whilst many others are 15-20 years from it.

And herein, of course, lies the problem with any discussion of generational difference: it avoids the fact that there is a massive class divide. Both the right and some of the narcissistic left avoid this fact. But some things are true whether you believe them or not.

* Damon was slightly younger than me, but the point holds.

September 30, 2016

Not trashing Thatcher

At this week���s Labour conference, Tom Watson told members to stop ���trashing��� the record of New Labour. This raises a paradox ��� that if any party should be attacking the record of a successful recent leader, it should be the Tories, not Labour.

Put yourself in the shoes of a Tory loyalist. You support Osborne���s introduction of a National Living Wage. But Thatcher was opposed to state intervention to support wages, and allowed Wages Councils to wither (though it was the Major government that finally abolished them). You want to withdraw from the single market if this is necessary to control immigration ��� but it was Thatcher who helped create that market. You want to reintroduce grammar schools ��� but Thatcher abolished many of them. You support Philip Hammond���s promise to ���reset��� fiscal policy ��� but Thatcher preached the need for ���good housekeeping.��� You���re worried that immigration will undermine traditional communities ��� but Thatcher destroyed many of these in mining areas. You support Ms May���s desire to put workers onto company boards ��� but Thatcher championed ���management���s right to manage.���

From this perspective, Tories should be trashing Thatcher���s policy. However, I very much doubt that her name will be booed whenever it is mentioned at next week���s conference, and Tories don���t use the word ���Thatcherite��� as a term of abuse in the way Labour members use the word Blairite.

Why is this? It���s not because, on domestic policy, Corbynistas are as distant from Blairism as May is from Thatcherism. They support New Labour policies such as tax credits, minimum wages and infrastructure spending.

Instead, there are other reasons. One is that Blair has become synonymous with the war in Iraq, whereas Thatcher was smart enough (or lucky enough) to start a war she could win.

Also, ���Thatcherism��� and ���Blairism��� function much as House Stark or House Bolton do ��� as indicators of tribal loyalties rather than ideology. Tories can think of themselves as Thatcherite even whilst renouncing many of her policies because they regard her as one of their tribe: she was on the right side of the class war. Even in his pomp, however, many Labour members never really regarded Blair as ���one of us���.

There���s something else. Tories don���t think so much about political ideas: they don���t ���problematize��� or ���workshop��� them. Instead, as Oakeshott said (pdf), governing is for them a ���specific and limited activity��� to be gotten on with rather than theorized about. This often leads them to value unity over theoretical arguments - at least when Europe isn't at stake. And because people aren���t very good at thinking, and because there���s a thin line between being principled and being a sanctimonious twat, this gives them a big advantage.

September 28, 2016

Immigration: the right's problem

A commenter on a previous post asks: why is immigration such an obsession on the left? To answer this question, let���s first note that the free market right should be strongly opposed to immigration controls.

This is simply because immigration is a matter of freedom. Restrictions on immigration deny people the freedom to live where they want; employers the right to hire whom they want; and landlords the right to let their property to whom they want.

I���m old enough to remember when rightists did indeed assert these freedoms. During the Cold War one of the biggest accusations against the USSR was that it denied its subjects the right to emigrate. And Norman Tebbit���s famous 1981 speech in which he praised his father who ���got on his bike and looked for work��� could be regarded as applauding free movement: if it���s praiseworthy to get on your bike and look for work, shouldn���t we also praise those who get on boats and planes to do so?

Few rightists today, however, proclaim the rights of migrants. Yes, some do such as Bryan Caplan and Sam Bowman. But such men have far less influence than their intellect and integrity merit.

This poses the question: why are so many Conservatives who have traditionally asserted the virtues of free markets so silent about the merits of migration?

You might say it���s because freedom is a matter of degree and must be limited to accommodate other goods.

But this won���t do, for three reasons:

- Many of those who want immigration controls also want economic freedoms to be restricted in other domains. Many Ukippers, for example, support (pdf) price controls and nationalization.

- A big case for freedom lies in the invisible hand ��� the idea that aggregate welfare increases when each individual is free to pursue his own goals. If you���re going to deny the benevolence of the invisible hand in the domain of immigration, it���s difficult to assert it in other domains, especially as the empirical evidence (pdf) suggests that (in economics at least), free migration is indeed benign.

- The goods with which immigration is alleged to conflict aren���t those which free marketeers value highly. Let���s concede that immigration does undermine social cohesion (something which I doubt). So what? Cohesion is a collectivist ideal which shouldn���t appeal much to free market individualists.

It should, therefore, be the right that is championing the virtues of immigration at least much ��� if not more so ��� than the left. So why isn���t it?

One possibility is that the right never truly believed in freedom anyway. They merely used the it as a stick with which to fight the ideological Cold War, and as a means of attacking workers. Now that these uses are no longer necessary, rightists are exposed as the freedom-hating bigots they���ve always been.

But perhaps there���s something else, or another way of expressing the point. The Tory party has for most but not all of its history been highly pragmatic, capable of ditching principles or prejudices when electorally necessary. It has managed to retreat from the free market rhetoric of Thatcher without great turmoil; Osborne's embracing of the minimum wage, for example, caused little fuss.

Much of the left, however, is more idealistic. And herein perhaps lies the answer to the question: why is it preoccupied with immigration? It���s because immigration embodies a conflict between principle and practicality: free(ish?) migration is good policy (from both left and right perspectives), but electoral disaster. The left feels this dilemma but the right ��� especially the populist element thereof ��� is less troubled by it.

September 27, 2016

Labour's advantages

���Perhaps Labour���s day is done, and it is time for something new��� says Nick Cohen, a sentiment echoed by Janan Ganesh.

I disagree. Labour has two massive things going for it, which are immense obstacles to the formation of a new party.

One is class. Britain is a class-divided society, and strong political parties must have a class base (which is of course not to say their support should be confined to a particular class.) Labour's ties to trades unions give it this, and any new party will lack it.

It's often said that our FPTP system militates against new parties, which is true. But this is often a reflection of the fact that the class divide is partly a geographical split, with post-industrial areas divided from posher ones.

The second obstacle ��� which is not unrelated to the first ��� is path dependency. Political parties, like successful brands, are products of history. People support Man Utd not because of Marouane Fellaini but because they were attracted to the team by the likes of Bobby Charlton and Paul Scholes and got into a habit which they can���t break. In the same way, some will vote for a pig if it wears a Labour rosette.

Take, for example, the Greens. In many ways, these are more attractive than Labour ��� and certainly more so than the intellectual and political vacuum that is the Labour right. They are sounder on immigration and, I suspect, civil liberties and their joint leadership betokens some freedom from the leadershipitis that disfigures Labour. Nevertheless, the lack of a class base and benefit of path dependency makes me doubt they can supplant Labour.

A glance at the historical record shows what I mean. One thing this tells us is that it is rare for big incumbent parties to collapse. This alone suggests that Labour���s obituarists might be guilty of the fallacy of base rate neglect ��� as well as of wishful thinking. Where parties have collapsed it���s been because they lack a class base, such as the Liberals in the 1920s, or have betrayed the perceived interests of much of that base as the Tories did in abolishing the Corn Laws in 1846. (Scottish Labour might also be an example of the latter).

Equally, new parties succeed where they have a class base ��� as Labour did in the early 20th century - but fail when they are the ego trip of a narcissist; think of Mosley���s BUF or David Owen���s SDP. It���s too soon to say into which category Ukip falls.

In saying all this, I am actually rejigging a point I made in a different context the other day. Judging political parties should be like assessing businesses. We must consider not merely or even mainly the calibre of the people running them: to do so is to commit the fundamental attribution error. We must also consider their structural advantages that come from history and market position. Very often, it is the latter that matter most. Warren Buffett has said that if these are strong enough an organization can survive being run by one���s ���idiot nephew���.

I fear, however, that the Labour party is testing this hypothesis somewhat more rigorously than I would like.

September 25, 2016

What Blairites?

Corbynistas have gotten into the habit of calling their opponents ���Blairites���. In some cases, this is unwarranted not because it is a smear, but because it is an unjustified compliment.

I mean this is two different senses.

One concerns immigration. Chuka Umunna thinks the UK should pay the hefty price of leaving the single market if necessary to impose immigration controls. And Rachel Reeves thinks Labour should listen to voters ���legitimate concerns��� about immigration ��� without telling us what exactly these are.

This desire for immigration controls fits uneasily with Blairism. For all his faults, Blair has always been pro-immigration. Back in 2005 he said that rising immigration was ���precisely what one would want and expect���. And even the latter-day debased Blair says that ���immigration is good for a country.���

And whilst he too speaks of voters ���legitimate concerns���, he at least spells out what these might be, rather than using the phrase as a dog-whistle. For example, he says voters sense that immigration is uncontrolled and that some incomers don���t share our values.

Herein, though, lies the problem: these concerns raise awkward questions. How do we reconcile voters��� desire for control with freeish markets? If hostility to immigration is motivated by fears they have different values, why are Poles being attacked as much as Muslims? If, as Nick suggests, it is based upon people valuing ���the familiar and the local��� why did they vote for the wrenching change of Brexit, and why is hostility to immigrants strongest in the least lovable parts of the country such as Margate or Harlow?

At his best, Blair did not pander to voters��� basest instincts but rather succeeded in reconciling sensible(ish) policies with public support. There���s little evidence that his epigones are doing this. Triangulation had three points, not the one.

Which brings me to the second way in which so-called Blairites aren���t really Blairite.

In the 1990s, Blair had the wit to see that the economy had changed and that this needed new social democratic policies. For example, tax credits and university expansion were based in the recognition that globalization was reducing wages at the bottom end of the labour market and increasing demand for graduates; the stress on economic stability was intended to offer footloose companies the security they needed to invest in the UK; the stress upon debt sustainability was meant to placate bond vigilantes who were demanding high returns on government debt. And so on.

Blair���s talk of newness and modernity wasn���t just tiresome spin. It was a recognition that social democracy had to acknowledge new economic realities. This is the case now. Today���s new realities are zero productivity growth and secular stagnation that require pro-growth policies; negative real interest rates that render activist fiscal policy feasible as well as necessary; job polarization that makes social mobility harder; the failure of top-down managerialism; and the shift in inequality from a high 90/10 ratio to a high take by the 1%.

Although John McDonnell has shown signs of seeing these, ���Blairites��� seem not to. Although David Miliband writes of secular stagnation, he doesn���t seem to have much idea what it entails for leftist policies.

We should therefore get out of the habit of calling Labour���s right ���Blairites���. They don���t deserve such a good name.

Chris Dillow's Blog

- Chris Dillow's profile

- 2 followers