Chris Dillow's Blog, page 65

February 22, 2017

Missing markets

Why is there such a long lag between good economic ideas and their implementation? I���m prompted to ask by the death of the great Kenneth Arrow.

He showed (pdf) that, under certain conditions, it was possible for competitive markets to achieve an optimal allocation of risk. One of these conditions is that there exist securities which pay out in all possible states of the world, so that we have in effect complete insurance markets. But, he concluded:

Many of the economic institutions which would be needed to carry out the competitive allocation in the case of uncertainty are in fact lacking.

He wrote that in 1952. Not much has changed since then. Yes, we now have index-linked gilts which pay out for all different possible rates of inflation. But we don���t have GDP-linked bonds that pay out in different rates of GDP growth, nor securities that pay out at different levels of house prices, or which pay out at different levels of occupational employment and so would offer insurance against our jobs being taken by robots. As Robert Shiller wrote in 1993 ��� 24 years ago! - we just don���t have markets that insure us against big economic risks: his book, Macro Markets can be seen as an attempt to operationalize Arrow���s high theory.

Why, then, has so little changed since Arrow wrote those words?

It���s not because his ideas are flawed: many far worse ideas have been adopted. Nor is it because the welfare cost of business cycles is small as Robert Lucas argued (pdf): recessions hit real people, not representative agents. Nor is it because the state does such a good job of insuring against economic risks that there���s no role for markets. Nor is it because there���s anything very unusual about this particular case; there was a gap of over 30 years, for example, between Ricardo arguing against the Corn Laws and their abolition.

Instead, I���d suggest other reasons.

One is simply a status quo bias. This isn���t wholly a bad thing. Things often exist or not for good reasons. The status quo might embody the wisdom of the ages. But a healthy scepticism can spill over into antipathy for change ��� as in the ���not invented here��� syndrome.

Another is that it���s easier for the financial ���services��� industry to make money by rigging markets or flogging over-priced products than it is for them to undertake genuinely worthwhile financial innovation. As William Nordhaus has famously shown, the private rewards to innovation are often small.

This might be especially true in finance. The worth of financial assets often lies in their liquidity, the ease with which they can be traded. Liquid markets, however, don���t fall from heaven. They need to be created which requires hard work. Donald MacKenzie discusses how Leo Melamed, then chairman of the CBOE, cajoled traders into trading index futures thus creating a market:

A market, says Melamed, ���is more than a bright idea. It takes planning, calculation, arm-twisting and tenacity to get a market up and going. Even when it���s chugging along, it has to be cranked and pushed.��� (An Engine, not a Camera, p173)

Perhaps Arrovian securities are lacking because there���s been no Melamed figure to chivvy them into existence. Markets don't exist because of a market failure.

In this context, markets and government are complements not substitutes. If we want macro markets the government might need to create them and give them away; if it can create money out of nothing it can create other claims on wealth too.

One point that critics and supporters of markets are both apt to forget is that, when viewed from the perspective of Arrow-Debreu theory, the astonishing thing about markets is how under-developed they are.

February 21, 2017

The left's Brexit dilemma

Jeremy Corbyn���s decision to accept the ���will of the people��� on Brexit has been forcefully attacked, for example by Ed Vulliamy ��� with some justification. I fear, however, that we are perhaps under-estimating the extent to which the left faces a genuine dilemma here.

This dilemma isn���t so much electoral as ideological. For me, the big, great idea of the left is the desire to empower working people. But this runs into the problem: how can we claim to want to empower people and yet say that the people were flat wrong on an issue where they were empowered?

In accepting the ���will of the people��� Corbyn has at least ducked this dilemma. And for Blair, it doesn���t even arise. He���s always believed in managerialism and leadershipitis and so can consistently argue that he knows better than the people. It���s in this context (and perhaps this alone) that it makes sense for his critics to raise the subject of Iraq; his decision to go to war highlighted the limitations of top-down central planning.

Some of us, however, do face the dilemma. Can we solve it? I think so, in four ways.

First, the plebiscite was the wrong form of empowerment. It did not fulfil the conditions under which there is wisdom in crowds ��� for example, that there be meaningful private information or that beliefs be uncorrelated. This doesn���t necessarily mean we should reject its result outright. But it does mean we should use it as a platform for arguing for meaningful empowerment. As I���ve said, if you think the plebiscite was a good idea you must, logically, think worker democracy an even better one.

Secondly, we should recognise (or pretend?!) that not everybody voted Brexit for consequentialist reasons. Some regard it instead as an intrinsic good: to them, being free of the ���yoke of Brussels��� is a good thing in itself. Once we do this, we can argue that Brexit, especially in the form pursued by Ms May, is costly. Goods have a price. That shouldn���t be surprising.

Thirdly, we should argue for ways of minimizing this price. That means arguing for the softest possible Brexit. But it also means pushing the case for supply-side policies that will give a boost to growth to offset the likely adverse effect of leaving the single market.

Finally, we should (re)claim ownership of the phrase ���take back control. As Will Davies has said:

The slogan ���take back control��� was a piece of political genius. It worked on every level between the macroeconomic and the psychoanalytic���What was so clever about the language of the Leave campaign was that it spoke directly to [a] feeling of inadequacy and embarrassment, then promised to eradicate it. The promise had nothing to do with economics or policy, but everything to do with the psychological allure of autonomy and self-respect. Farage���s political strategy was to take seriously communities who���d otherwise been taken for granted for much of the past 50 years.

We should be arguing that we should empower people not just to vote upon the obsession of a few rich cranks but to take control of their own lives. This means giving them a greater say in local public services; freeing them from the oppressive and demeaning aspects of the welfare state; and giving them more say in the workplace. It is to his great credit than John McDonnell is thinking along these lines ��� and to the great discredit of many others that his efforts aren���t getting more attention.

February 17, 2017

Replacing Wenger

Should Arsene Wenger go? If so who should replace him? In considering these questions we must remember three important economic principles.

One is that in hiring someone what matters is putting round pegs into round holes. Productivity often results not from the intrinsic quality of a worker, but from the match between his skills and the job. What matters is getting the right man for the job, not necessarily the best.

Boris Groysberg has shown this (pdf). He looked at 20 former managers of General Electric ��� a company with a reputation for producing good bosses ��� who moved to senior positions in other firms. He found that their performance varied enormously even though all 20 had similarly impressive CVs.

This variance occurred because the matches differed. Hiring a cost-cutter, for example, is a good idea for a firm facing stiff price competition in a mature industry. But it���s a bad idea if yours is a fast-growing newer firm. And conversely, a man whose good at managing growth won���t fit into a mature firm.

What Arsenal must ask, therefore, is two questions. First, what precisely is the problem we want to solve? And second, who has the skill-set to do so?

The problem seems to be one of mentality: how to ensure that good players don���t collectively under-perform in big games. Also, we���d like someone who���s good at managing up ��� who can get money and competence in the transfer market out of an ���absentee owner with no knowledge or interest in football��� and a board which has been occasionally clueless.

So, who fits this bill? There are few stand-out candidates. There���s nothing in the CVs of Eddie Howe, Thomas Tuchel or Ronald Koeman to suggest they are capable of taking a team from the top four to the top one. Yes, Diego Simeone or Max Allegri have a proven record to suggest they could do so ��� but the former at least would entail a massive and therefore risky cultural change at the club.

But here���s a problem. A CV tells us what a man has done ��� which might of course be just ���got lucky���. It doesn���t necessarily tell us what he can do.

Which brings me to the second principle: nobody knows anything. Success is to a large extent unpredictable. This is as true in football management as business. For example, Sir Alex Ferguson was on the brink of the sack in 1990, and Bill Shankly failed to get Liverpool promoted in his first two seasons on charge ��� something which would get a boss the boot in our more demanding times. Nobody then foresaw their great achievements ��� just as nobody���s reaction to Claudio Ranieri���s appointment at Leicester was ���this guy will take them to a league title���.

The converse, of course, is also true. Countless managers have failed to live up to fans��� or board���s hopes, even at the minority of clubs that aren���t run by egomaniacs or idiots: David Moyes and Louis van Gaal were both the right man for Manyoo once.

So, what can we expect of a new Arsenal boss?

Here���s my third principle: perhaps not much. We���ve got reasonable evidence (pdf) from top European leagues that changing manager does not in fact make much difference on average. This is perhaps consistent with the fact that any organization���s success often depends more upon organizational capital than upon single individuals. For example, some teams will always be near the top, and others won���t: last season was an outlier in this respect.

Maybe Great Men can make a difference. But the thing about Great Men is that they are very rare.

I guess the only point I���m making here for Arsenal fans is: don���t get your hopes up.

February 16, 2017

Healing Labour's class divide

There���s an emerging consensus that the Labour party���s longstanding coalition between workers and middle class intellectuals is breaking down. Bo Rothstein says the ���alliance between the industrial working class and what one might call the intellectual-cultural Left is over.��� Julian Coman laments the division ���between Labour and its own traditional supporters in the heartland towns of the Midlands and the north.��� And Peter Ryley says the left ���has lost its ability to speak for and to working class people.���

We need a historical perspective here. There has always been a tension on the left between workers and the middle class. This was forcefully expressed by George Orwell. Describing an ILP meeting in London, he wrote:

Every person there, male and female, bore the worst stigmata of sniffish middle-class superiority. If a real working man, a miner dirty from the pit, for instance, had suddenly walked into their midst, they would have been embarrassed, angry, and disgusted; some, I should think, would have fled holding their noses.

Just a few years later, however, a Labour government laden with superior middle class types created the modern welfare state: the Wykehamist Stafford Cripps was even one of the vegetarians that Orwell so despised. And all subsequent Labour governments were well stocked with poshos.

Why then should the alliance be breaking down now?

One reason is that the issues that have long divided workers and the well-meaning middle class are more salient now ��� most obviously Brexit. This perceived split might be exaggerated by a cartoonish stereotyping of the ���white working class��� as insular xenophobes fleeing into the arms of Ukip ��� an image which ignores the fact that Ukip is the party of multi-millionaires such as Farage, Banks and Nuttall*.

A second reason is perhaps that the social distance between the classes ��� especially at the top of the Labour party - has increased because of the decline of unions and autodidacts. The posh members of the 1945-51 government were daily reminded of their links to workers by their colleagues such as Bevin and Bevan. In recent years, the link has been weaker: yes, Blair had Prescott ��� but whereas Bevin and Bevan were respected and feared, there was always an element of patronization in the treatment of Prescott.

Perhaps linked to this is something else. Since the 1990s the middle-class superiority of which Orwell complained ��� which had been restrained by trades union power ��� has been unleashed. New Labour���s managerialism and embrace of bosses helped to alienate working people. And this continues to this day. Julian Coman describes how Wigan residents are angry at the ���top-down high-handed way��� a Labour council wants to destroy part of the green belt, and how working people feel ���a sense of powerlessness.���

What we���re seeing in the UK might therefore be the same thing Joan Williams describes in the US ��� workers��� resentment at professionals who ���order them around every day.���

There is, however, a solution to this. Let���s go back to Orwell:

To the ordinary working man, the sort you would meet in any pub on Saturday night, Socialism does not mean much more than better wages and shorter' hours and nobody bossing you about.

This is just what socialism should mean. Having ���nobody boss you about��� is desireable in itself, as Marc Stears argues. It is also economically efficient: worker democracy raises productivity.

And better wages is not a narrowly economistic demand. As Ben Friedman has shown, it���s a necessary basis for greater tolerance and liberalism and hence many of the things the middle class left (rightly) want.

What Labour needs, then, is a focus upon issues of control (not just in the workplace but more widely) and incomes. Whether it can do this is another matter.

* I assume Nuttall must be wealthy, given that he invented the internet and played for Real Madrid.

February 15, 2017

Low job mobility

It���s sometimes said that we live in times of unusual economic uncertainty, with new businesses disrupting old ones and robots threatening to take our jobs. Today���s labour market data seem to undermine such claims, as they show unusual stability in jobs.

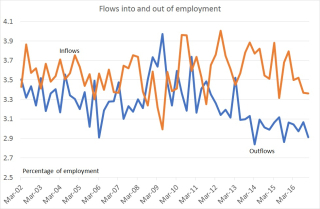

My first chart shows one measure of this: inflows and outflows into and out of employment, as a percentage of total jobs. If we were seeing high rates of disruption, we���d expect to see lots of people lose their jobs either to robots or as their employers shrink under competition from new rivals, and lots of job creation as new businesses take on staff.

Which is what we���re not seeing. Outflows from employment in particular are lower than they were before the crisis.

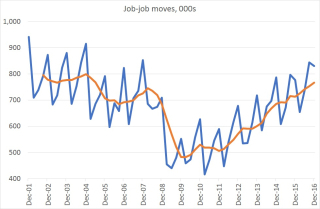

My second chart shows moves from job to job: because the data aren���t adjusted for seasonal swings, the orange line shows a four-quarter moving average. This shows that whilst such moves have risen sharply since the recession, they too are below the levels we saw in the early 00s.

What we have here is evidence that the pace of creative destruction is lower now than it was pre-crisis. I suspect this is closely linked to the fact that productivity growth has been sluggish for years. This is partly because labour mobility should improve productivity by ensuring that round pegs go into round holes ��� that workers are well-matched to jobs. But it���s also because a lot of productivity growth comes not from existing firms upping their game but from (pdf) entry and exit. Low rates of labour mobility are a sign that entry and exit is low.

All this is a two-edged sword. The good news is that it suggests that job security has risen. This is consistent with the fact that we���ve seen strong consumer borrowing and spending in recent years.

The bad news isn���t simply that it is also a sign of weak productivity. As the Resolution Foundation has said (pdf), low mobility ���may have concerning implications for young people���s career prospects.��� This is because:

Job mobility is generally a key enabler of pay progression and career advancement, and this is particularly the case for young people as they build careers, find roles in which their productivity will rise, and make progress up the earnings curve may have concerning implications for young people���s career prospects.

This might have nasty political implications. Saliha Metinsoy says declining job mobility in the US contributed to Trump���s victory because it increased people���s frustration with their lack of job prospects.

All this poses big and serious questions: what, if anything, can be done to foster greater creative destruction? How can we achieve the upsides of a fluid labour market ��� productivity growth and better prospects for younger workers ��� whilst avoiding the downside of insecurity? (Hint: citizens income). I don���t, however, expect politicians to have good answers to these.

February 14, 2017

House prices as leaky bucket

The Resolution Foundation says (pdf) that the typical pensioner now has a higher income, after housing costs, than the typical worker. Which poses the question: do younger people have a legitimate complaint here? I think the answer���s yes.

First, though, let���s see what their grievances are not.

They can have no complaint about rising pension incomes because of the triple lock. Quite the opposite. The power of compounding means this will benefit tomorrow���s pensioners ��� ie today���s youngsters ��� more than it helps today���s old folk. (Those who complain that the lock won���t last ignore the fact that it is as sustainable as we want it to be.)

Nor can they complain about high pensioner incomes to the extent that these are due to more pensioners having jobs; the number of over-65s in work has doubled since 2005. There isn���t a lump of labour, so pensioners don���t displace young workers, any more than immigrants do*.

And whilst they do have a legitimate complaint about low pay, this is not a generational issue but rather one about macroeconomics and class.

Instead, youngsters��� legitimate beef is about house prices. A big reason why pensioners are better off than them is that many pensioners live mortgage-free in houses they bought cheaply years ago, whilst young folk must pay a fortune in rent or (for a lucky few) mortgage payments. As David Willetts wrote in The Pinch, this is in effect a transfer of wealth from young to old.

The issue here is not merely that the old did nothing to deserve this wealth: no, stoking up bubbles and restricting supply doesn���t count. It���s that this transfer is inefficient.

Arthur Okun said (pdf) that transferring income from rich to poor was like carrying it in a leaky bucket. Because of administrative costs and adverse effects upon incentives, he claimed, transfers reduce aggregate incomes.

But there���s also a leaky bucket when the young transfer their wealth to the old. This is because there are good reasons to think that high house prices are bad for growth. For example, they impede labour mobility or force people to take long commutes which reduces their productivity. They encourage nimbyism and so delay infrastructure spending. They divert resources towards sectors with low productivity growth and so reduce overall growth: if youngsters didn���t spend so much on rent, they���d have more to spend on other things, which would help promote innovation and entrepreneurship. In encouraging high debt, they increase the risk of financial crises which have long-lasting adverse effects on growth. And then there���s the longer-term cultural effect: if people can get rich by sitting on their arses and seeing their house price increase, they���ve less incentive to work, save or set up new businesses.

Granted, there���s a potential offsetting effect: rising house prices create collateral which allows some people to borrow to set up new businesses. But I think it plausible that, net, high house prices are bad for growth.

Which means that the transfer from young to old is a negative-sum one. Okun was happy to use a leaky bucket to transfer cash from rich to poor. The case for using one to transfer from young to old is, however, far more questionable.

To this extent, youngsters do have a real grievance, as they are on the wrong end of a redistribution which is bad for the aggregate economy.

* This poses the question: why do people complain about immigrants taking their jobs but not pensioners?

February 13, 2017

The trouble with experts

Paul raises an important issue: what���s wrong with experts? I suspect the answer is: plenty.

These many faults, however, don���t include the failure to foresee the financial crisis. It���s not the job of economists to act as soothsayers, any more than we expect mechanics to predict the next fault with our car, or doctors our next illness. There���s a lot of good economists can do without prophecy.

Instead, one problem is that experts ��� in public at least ��� don���t sufficiently identify what Charlie Munger called the edge of their competence: they don���t say what they don���t know. The problem with economists isn���t so much that they didn���t foresee the crisis as that they failed to tell the public that recessions are unforecastable (at least by mainstream techniques?) In 2000, Prakash Loungani reported that the economic consensus had failed to predict almost every recession, and AFAIK, not much has changed since.

Of course, there���s nothing unusual about economists in this regard. Gerd Gigerenzer said that doctors are ���often wrong but never in doubt���; bosses rarely openly discuss the limits on their ability to control business; bankers don���t often admit to being unable to manage risk; fund managers don���t publicly say that markets are largely efficient; and so on.

I fear that academics��� pressure to publish exacerbates this error. As Andrew Gelman has consistently argued, the ���pgiven us a lot of bad science. This can weaken public confidence. One recent example of this is the claim that roast potatoes cause cancer. This ran into the common-sense problem that everybody eats roasties but only a few get cancer, which tells us that the link, if any, must be weak. It���s this sort of thing that generates the sentiment ���Experts ��� what do they know?���

In this context, we should remember a point made by William Easterly ��� that ���experts are as prone to cognitive biases as the rest of us���. One of these is overconfidence. Another is that groupthink can generate intellectual fashions, such as perhaps the dominance of DSGE models.

Perhaps another facet of this overconfidence is the presumption that knowledge and expertise must be centralized, within a single mind. But as Hayek pointed out, in some contexts this is not the case. Instead, knowledge can be fragmentary, tacit and dispersed. Consumers, for example, might be better economic forecasters than the experts ��� as might bond markets. And workers might sometimes know more than bosses.

Which brings us to a big problem. We are too often given the impression that experts are on the side of power. In part, this is the fault of the media: bosses, for example, are routinely presented as a priestly elite rather than as mere rent-seekers.

But the fault also lies with experts themselves. Economists fail to stress sufficiently that some of the settled findings of their discipline undermine claims to power. For example, the efficient markets hypothesis tells us that fund managers are charlatans; the prevalence of diseconomies of scale suggests that bosses aren���t as much in control as they pretend; and public choice economics warns us that those in power are often just rent-seekers.

In this context, even an otherwise admirable empiricism can be reactionary. Studying the effects of the small actual and feasible tweaks to capitalism means the question of big changes gets marginalized. In this way, as Paul says, economists unwittingly accept capitalist realism (pdf).

Related, to this, mainstream economists have been insufficiently awake to distributional issues. The default ethical criterion in economics is Pareto efficiency. So, for example, we���ve accepted globalization because it is potentially Pareto efficient: the gains from it to western economies are bigger than the losses. This has blinded us to the fact that a potential Pareto improvement in which the losers don���t in fact get compensation is a much more dubious matter.

If economists had a different default mental model, they���d have been better able to press the case for policies that really do benefit everybody. If economists used Rawls��� difference principle ��� which stresses the need for policies and institutions that ���are to be to the greatest benefit of the least advantaged members of society��� ��� they���d be much more conscious of inequality.

We all know that a gap has emerged between experts and the public ��� expressed in that heckle, ���That���s your bloody GDP. Not ours.��� If the quality of public discourse is to be lifted out of the gutter, this gap must close. At least part of the onus on doing so lies with the experts themselves.

February 10, 2017

The case for privatization

The FT says the government���s decision to sell off some student loans ���makes no sense.��� From one perspective, this is true: it���s daft to sell an asset that probably has a positive return in order to pay off debt that carries a negative real interest rate. From another perspective, however, there is a kind of logic to it.

One key function of the state is to help maintain capitalist profitability. This isn���t simply because the state is the executive committee of the bourgeoisie. It���s because decent public services require a healthy economy, which in a capitalist economy requires profits to be high enough to finance and encourage investment.

But here���s the problem. In our era of stagnation, profitable opportunities are lacking. This is why business investment has been weak since the late 90s; why banks invested in mortgage derivatives rather than proper assets; and why we are bombarded with calls from people claiming to sell us compensation for PPI mis-selling or accidents we���ve not had. When real investment opportunities are lacking, we get stagnation and malinvestments.

Quite why this should be is a big question: some say it���s because profits have fallen (pdf); others because risk (pdf) has increased.

Whatever the reason, there���s a need for state action to support profits.

One way it can do this is to sell off profitable assets it owns such as council buildings or student loan books. It���s probably better for macroeconomic stability that banks make money by ripping off students than that they chase risk like they did in the mid-00s.

Another trick is to outsource ��� giving private firms cash to collude with criminals, miscalculate tax credits, build schools that fall down and, I suppose, occasionally do something useful. Although outsourcing companies��� share prices have fallen recently, most of them have generated lots of cash.

I say this because I suspect that what we have here is another example of something I mentioned recently ��� a tendency for our economic views to be shaped by our formative years as well as by present reality. Because capitalism was dynamic back in the 80s and 90s, we tend to over-rate its dynamism now. As a result, we under-rate the extent to which it needs state aid to generate profits. Privatization and outsourcing are means of doing this.

You might object here that there are more intelligent ways for the state to expand profit opportunities ��� for example by expansionary fiscal policy, stopping Brexit or state support for innovation.

Such options are ruled out for political reasons: what we have here is an example of the relative autonomy of the state. Even if they weren't, however, they would have limits from a capitalist point of view. Fiscal expansion might eventually generate wage militancy; stopping Brexit might create a populist backlash and hence instability; and innovation would increase creative destruction and hence threats to incumbent firms. This creates a space for cronyism such as outsourcing and privatization.

Such policies might not always make sense from a conventional point of view. But then, the logic of capitalism isn���t necessarily rational from other perspectives.

February 9, 2017

"Incentives" as bigotry

Amber Rudd says she���s stopping child refugees entering the country because ���we do not want to incentivise perilous journeys to Europe particularly by the most vulnerable children.��� This should remind us of an old trick of the Tory party ��� the ideological misuse of the language of incentives to justify their own prejudices.

For example, we���ve been told for years that the rich need high pay and low taxes to incentivize effort. This, though, is deeply doubtful. Financial incentives can crowd out intrinsic motivations: bankers��� serial criminality (rigging Libor and FX markets; PPI mis-selling; and so on) suggests that bonuses crowded out professional ethics. They can encourage short-termism or cooking the books. They can discourage creativity (pdf). They can worsen performance by over-motivating people. And they can create inefficiencies by encouraging (pdf) workers to focus upon jobs that are easily monitored to the detriment of other important tasks ��� as when teachers teach to the test.

One simple fact should tell us that all these adverse effects can add up: that the UK���s GDP growth rate has been worse in the 28 years since Nigella���s dad cut top tax rates in 1998 than it was in the previous 28 ��� 1.5% against 2.5%.

At the same time as telling us that the rich need big carrots, the right has long told us that the poor needed sticks in the form of welfare reform to incentivize them to get jobs. This claim too is doubtful. To a large extent, it is job opportunities that get people into work, not benefit reform.

A scientific assessment of incentives requires careful analysis of tricky questions: how do income and substitution effects net out ��� a matter which differs from worker to worker? What margins of adjustment do people have? What are their information sets: do they know what options they have? And so on.

Tories, however, neglect such issues. They know ��� regardless of facts ��� that the rich need carrots and the poor need sticks. As George Carlin said:

Conservatives say if you don���t give the rich more money, they will lose their incentive to invest. As for the poor, they tell us they���ve lost all incentive because we���ve given them too much money.

All we���re seeing in Rudd���s lamentable words is an extension of this mindset to Syrian children. Talk of incentives merely provides a pseudo-scientific justification for small-minded bigotry.

February 8, 2017

For a delayed fiscal tightening

Our perceptions of the economy are shaped not just by current reality but also by the past. For example, Ulrike Malmendier and Stefan Nagel have shown (pdf) that people who experienced recessions in their formative years are more risk-averse than others even decades later; workers in the 1950s accepted low wage rises despite a tight labour market because they were cowed by memories of the Great Depression; and I struggled to believe that inflation could stay low in the 90s because my views were shaped by memories of the high inflation of the 1970s.

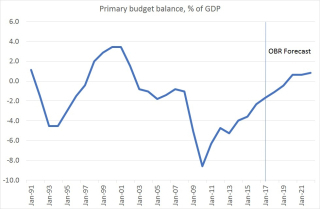

I suspect a similar motive lies behind the notion that the government must reduce its borrowing soon. Such a view makes sense if you think highish real interest rates are normal ��� as they were in our formative years. But it���s not so sensible when rates are negative.

20 year index-linked gilt yields are now minus 1.6 per cent. This means that if the government borrows ��100 now it will have to repay only ��72 in real terms. Which of course means that debt can shrink even if the government runs a deficit today. The maths of debt sustainability tells us that we can stabilize the current ratio of government debt to GDP even if the government runs a primary deficit (borrowing excluding interest payments) of around 2.9% of GDP. Its deficit this year will be only 1.1%, according to the OBR.

Richard Murphy is therefore right: there is no need for the government to balance its budget and no need for the forthcoming austerity described by the IFS.

Two counter-arguments to this won���t do.

One is that I���ve assumed gilts yields stay low, which they mightn���t do.

True, yields could rise ��� as the IFS says. But the government has to a large extent locked in lowish rates because it has borrowed long; the average maturity of government debt is 18 years. This means higher yields won���t immediately gravely raise debt interest payments. Also, yields are most likely to rise if the global economy proves stronger than expected. But the same stronger activity that raises yields would quite probably also raise tax revenues.

A second argument is that higher government borrowing would raise inflation by strengthening the economy. This, though, is a feature not a bug. We want to get interest rates away from their zero bound, so that conventional monetary policy can act as a cushion when the next downturn comes. Higher inflation is a way to achieve this. There is a strongish case for the macroeconomic policy mix shifting to looser fiscal and tighter monetary policy.

None of this is to say that fiscal policy should never tighten. It should, when real interest rates are at more ���normal��� levels. When this is the case, there���ll be a case for budget surpluses both to stabilize the debt-GDP ratio and to prevent a tightening of monetary policy that pushes rates very high.

Obviously, we are not yet at this stage. Fiscal tightening should thus be delayed.

Such a delay should be used wisely. We should regard it as a chance to better organize the public finances ��� to ask what sort of tax base we want; what should be the mix of tax rises and spending cuts; and how to find genuine efficiency savings in the public sector ��� a question which of course requires a knowledge of ground truth which only workers themselves can provide. If such a debate helps to legitimate austerity, it would also help make it more credible and sustainable.

If we had an intelligent politics ��� which is a big if ��� a delayed fiscal tightening would be a better tightening.

Chris Dillow's Blog

- Chris Dillow's profile

- 2 followers