Chris Dillow's Blog, page 61

May 8, 2017

"Strong and stable"

Whenever I���m faced with a particular claim, I like to ask: what would count as empirical evidence here? So let���s apply this test to Ms May���s claim that she offers ���strong and stable��� leadership. What evidence could there be here?

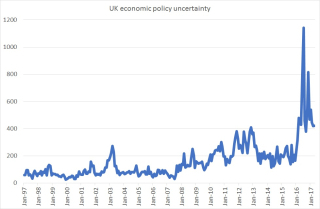

There���s one obvious test ��� the indices of economic policy uncertainty complied by Scott Baker, Nick Bloom and Steven Davis. If a government offers strong and stable leadership, it should deliver low policy uncertainty. So, do the Tories do this?

No. Under the 1997-2010 Labour government, the monthly policy uncertainty index averaged 93.9. Under the Tories, it has averaged 286.

We���ve also got daily data since 2001. This shows that the uncertainty index averaged 208 during Blair���s premiership, 299.8 under Brown���s, 300.7 under Cameron���s and 467.5 under May���s*. The data therefore show that May has given us less ���strong and stable��� leadership than her three predecessors.

Now, you might object here that policy uncertainty isn���t wholly within the control of the government; it���s affected by exogenous events. You���d be wholly correct. The higher uncertainty during Brown���s premiership, for example, was due to the banking crisis for which he was (at most) only partly to blame.

But Brexit isn���t exogenous. It���s the result of David Cameron���s weak leadership: his caving into euro-obsessives by offering a referendum; his pursuit of austerity policies that fuelled resentment at immigrants: and his failure to convince voters to stay in the EU. And yet he too claimed to be offering the same ���strong and stable��� leadership that May���s offering. In 2015, he tweeted:

Britain faces a simple and inescapable choice - stability and strong Government with me, or chaos with Ed Miliband

That now looks laughable. Which raises the question: why isn���t May���s claim seen as anything other than as risible as that?

One reason is that political journalists don���t ask the question I do. They under-rate the importance of ground truth and take politicians at face value. So they believe May offers stability just as they believed that Osborne���s talk of a ���northern powerhouse��� meant he believed in devolution when in fact his cuts to local government resulted into more power being centralized in Whitehall.

Another reason is that the Tories are the natural party of government whereas Labour are not. And Labour���s promise to raise taxes on the well-off, of course, means the party is a threat to the only people who matter. The rich have always mistaken their own interests for the national interest.

And I���ll concede that Jeremy Corbyn���s incompetence and ill-discipline means he is ill-equipped to negotiate Brexit**. The Tories, however, are in no position to point this out. Their claims that Labour can���t deal with Brexit sound like the whines of a Bullingdon boy who, having puked up all over his room, complains that his scout isn���t cleaning up properly.

Whatever the reason, though, one thing is clear. Tory claims to offer ���strong and stable��� leadership are simply inconsistent with the facts.

* The monthly and daily indices have different bases, so aren���t comparable with each other.

** This isn���t true of his colleagues, though. Keir Starmer���s legal background suggests he���s better qualified to negotiate than most others are.

May 7, 2017

It's not the economy, stupid

It looks as if the conventional wisdom is wrong. For years, this has been that elections are determined by the economy ��� as embodied in the slogan, ���it���s the economy, stupid.��� This election, however, looks like being an exception.

Ms May seems to be getting her wish that the election should be about Brexit, even though the move will probably impoverish us. Years of stagnating real wages have not produced a backlash against the government. Voters support immigration controls even though these are bad for the economy*. And the question of how to raise productivity ��� which many economists would regard as the biggest economic issue ��� hasn���t so far been on the election agenda at all.

This raises the question: why doesn���t the economy seem to matter in this election?

We can discount the possibility that voters are so far up Maslow���s hierarchy of needs that they are now above material concerns.

What, then, are the explanations?

One possibility is that many retired voters needn���t worry about the economy because they are protected from the consequences of weak growth by the triple lock. Yes, I���m a supporter of this, but perhaps one drawback of it is that it reduces solidarity between working and retired people.

Another possibility is that there���s wisdom in crowds. Maybe voters instinctively grasp that there���s not much governments can do to raise trend growth. I���m not sure about this, though. There are many policies which might increase productivity and which wouldn���t hurt us even if they don���t, such as better early years education. Maybe there���s an analogy here with broad-spectrum antibiotics: if you don���t know the precise problem, throwing a range of solutions at it might work.

Thirdly, Labour has failed to put economic issues on the agenda. I���m not sure this is wholly Corbyn���s fault ��� although his perceived incompetence no doubt tarnishes Labour���s reputation generally. Remember that he won the leadership election because his more centrist opponents were devoid of ideas. John McDonnell has certainly been thinking along the right lines, but Labour policy has so far been a work in progress rather a polished proposal.

A fourth explanation is media bias. I���m not thinking here of overt bias against Corbyn: as Jonathan Freedland points out, Corbyn is unpopular even with people who avoid the MSM. Not even am I thinking about moronic mediamacro. Instead, I���m thinking of a different type of bias. Journalists report upon what people do. But this means they focus upon agency more than upon emergent processes: they talk to ���senior sources��� rather than analyse impersonal social phenomena. This distorts what gets covered: fiscal policy and Brexit talk gets attention whereas stagnant productivity gets less.

There is, though, another possibility ��� endogenous (pdf) preferences. Rather than protest against stagnation, voters have resigned themselves to it ��� perhaps in a similar way to how they resign themselves to inequality. This, however, poses the question asked by Jon Elster:

Why should individual want satisfaction be the criterion of justice and social choice when individual wants themselves may be shaped by a process that pre-empts the choice? (Sour Grapes, p109)

At a time when the ���will of the people��� cannot be doubted, this question is, however, off the agenda.

* Yes, most voters say they wouldn���t pay anything to reduce immigration, but the juxtaposition of this with the popularity of immigration controls only shows how little people have thought about the economics of immigration.

May 4, 2017

On extra-parliamentary action

What can parliamentary politics achieve? Not much, says Paul Mason:

Elected politicians have little power; Wall Street and a network of hedge funds, billionaires and media owners have the real power, and the art of being in politics is to recognise this as a fact of life and achieve what you can without disrupting the system.

On the other hand, though, Danny Finkelstein attacked John McDonnell yesterday for being ���contemptuous��� of the idea that we can achieve socialism through parliament alone.

Here, I side mostly with Mason and McDonnell against Finkelstein. In many of the main social changes of my lifetime, parliament has played a relatively minor role. For example:

- Brexit. Most MPs wanted us to remain in the EU. We got out because Cameron called the referendum in part because of pressure from Ukip, and Leave won because of the work of people who weren���t MPs. If you want an example of effective extra-parliamentary political action, you should look at Farage more than any leftist.

- Gay rights. Isle of Wight MP Andrew Turner recently resigned after making homophobic remarks. When I was a young man, however, an election campaign was based successfully upon homophobia. This huge change, from gays being stigmatized and homophobes accepted, to the exact opposite was achieved mostly without parliamentary intervention but by changes in social attitudes. Yes parliament legalized homosexuality in 1967, but that alone did not remove anti-gay sentiment.

- The decline in crime. This is unlikely to be mainly due to government policy, simply because (pdf) crime has dropped in many countries with different policies. Instead, socio-technical changes are more responsible. Stuff is harder to steal, and young people play computer games rather than hang around on street corners.

- Greater gender equality. As Jeremy Greenwood has shown, this is due more to technical change than legislation. The greater availability of contraception not only gave women control over their fertility but also helped destigmatize pre-marital sex. And household technologies freed women up to enter the labour force.

Now, I���m not saying that parliament is irrelevant. It did play some role in the changes I���ve mentioned. The Equal Pay Act helped increase gender equality, for example, and the repeal of section 28 helped destigmatize homosexuality. Both, however, followed extra-parliamentary campaigns. And of course, increased inequality since the 1970s is due at least in part to parliamentary politics such as anti-union legislation and lower top tax rates. Remember, though, that those policies were themselves the product of extra-parliamentary action by right-wing think-tanks aimed at changing ideology.

Nor do I want to side wholly with Mason against Finkelstein. I fear that in attributing power to hedge funds and media bosses, Paul under-rates the importance of emergence and endogenous ideology. And I agree with Danny that placard-waving is often ineffective and that permanent revolution is ���preposterous.���

Nevertheless, the evidence suggests that parliamentary politics alone does not bring lasting social change. It might be necessary for such change ��� we���ll not get a citizens basic income without it but this too requires an extra-parliamentary campaign first ��� but it���s not sufficient. A stronger parliamentary Labour party is much to be desired. But this alone is not enough to achieve the sort of changes we on the left want.

May 3, 2017

Scale neglect, and bad interviews

The general election campaign begins officially today, so let���s think about colonoscopies.

In the winter of 1994-95 doctors in Toronto performed colonoscopies on patients and later asked them to recall how uncomfortable the experience was (pdf). They found that those patients who had the tip of the colonoscopy left in their rectum for a few minutes after the procedure recalled the experience as less unpleasant than those who had the colonoscopy removed immediately. This is evidence of what Daniel Kahneman calls (pdf) duration neglect; our memories of experiences are ���radically insensitive to duration.���

Here���s another story. Constantinos Antoniou and Christos Mavis have found a systematic bias in betting on men���s tennis matches. Bookies offer more generous odds on the better player in five-set matches than they do in three-set ones. They fail to appreciate that quality is more likely to tell in longer matches, whereas randomness favours the lesser player in shorter ones.

And here���s a third. People are massively wrong about many basic social facts ��� for example, they hugely over-estimate the number of immigrants in the UK, the amount of benefit fraud or spending on foreign aid.

These three points seem different. But they have something in common. They show us that people are bad at judging scale. They just don���t get proportions right.

Which brings me to Diane Abbott���s interview yesterday. Yes, it was awful. But it poses three questions:

- Is this a story about Ms Abbott, or about the general standard of MPs? Yes, she revealed a horrible lack of mental agility and feel for numbers. In this, though, she is not alone. Less than half of MPs can correctly answer a question as basic as ���if you spin a coin twice, what is the probability of getting two heads?��� As Janan Ganesh says, politics is not well-stocked with talented people.

- To what extent is an interview with a local radio station evidence of ability? I said yesterday that being good at interviews might be a sign of dangerous over-confidence. By the same token, being bad at interviews need not be evidence of a lack of ability. There���s a big difference between keeping one���s head when under pressure and being able to take good decisions at leisure in the comfort of one���s desk when surrounded by civil servants and spads who can provide you with facts and logic.

- How great was Ms Abbott���s mistake? Errors are ubiquitous in politics and inevitable. And by those standards, Ms Abbott���s incoherence barely registers. Boris Johnson wasted ��37m of taxpayers��� money on a non-existent bridge; the last government wasted over ��1bn on the cancer drugs fund; George Osborne cost the economy tens of billions in needless austerity; David Cameron called a needless referendum in the mistaken belief he could win it; Tony Blair took us to war on the basis of errors of judgment which should have been widely known. And so on and on.

All those errors were due to persistent and corrigble mistakes, rather than to heat of the moment confusion. And all had effects which were orders of magnitude worse than Ms Abbott���s.

From this perspective, the fuss about that interview is yet another example of scale neglect. The same professional and amateur pundits who are getting hysterical about a ���car crash interview��� (these people love their clich��s) also regard Johnson, Blair and Osborne as ���credible��� despite making much more expensive mistakes, without the excuse of momentary lapses.

But I wonder. Perhaps in thinking in terms of mistakes and costs I���m missing the point. What pundits want from politicians is slickness and confidence, and just don't care that this might well be a front for grotesque incompetence. In failing to provide this, Ms Abbott committed a solecism as grave as that of the man who wears brown shoes in the City or who tries to get into a gentleman���s club without wearing a tie ��� something which is utterly unforgivable.

May 2, 2017

Costs of overconfidence

Ben Chu is absolutely right to bemoan the damaging effects of overconfidence. I���d just add a few things.

One is that overconfidence can be a form of strategic self-deception. A new paper by Peter Schwardmann and Joel van der Weele shows this. They got subjects to do intelligence tests and then selected some at random and told them that they could earn more money if they could convince other subjects that they had performed well on the tests. They found that the selected subjects were even more overconfident about their performance than non-selected ones.

This is evidence for strategic overconfidence: people deceive themselves in order to better deceive others. I suspect this ��� or perhaps just ordinary deception ��� is common in debating societies and newspaper opinion pieces.

And overconfidence ��� strategic or not - succeeds. Schwardmann and van der Weele also show that the overconfident subjects were rated as smarter by evaluators. This corroborates a finding by Cameron Anderson and Sebastien Brion, that overconfidence is wrongly perceived as a sign of actual competence. This is one reason why job interviews are a bad way of selecting people (pdf).

Schwardmann and van der Weele say:

Overconfidence is likely to be more pronounced in settings where its strategic value is highest ie where measures of true ability are noisy, job competition is high and persuasion is an important part of success. Accordingly, we would expect overconfidence to be rife amongst high level professionals in business, finance, politics and law.

We might add bosses and journalists to this list.

This is not to say that strategic self-deception is all there is: Schwardmann and van der Weele estimate its only one-third of the story. People are also overconfident even when they lack extrinsic incentives to be so.

I fear that this overconfidence has systematically distortionary effects, in at least three ways:

- As Ben says, it perpetuates inequality. People from posh or rich backgrounds are more likely to be overconfident than others, and hence more likely to get jobs - because they are more likely to push themselves forward as well as more likely to be selected when they do. Trump���s discovery that being president isn't as easy as he thought it would be echoes Toby Young���s finding that running a free school is harder work than thought, and David Cameron���s discovery that he wasn���t in fact ���rather good��� at being prime minister.

- It���s not just political candidates who are overconfident. So too are some voters. Erik Snowberg and Pietro Ortoleva show that this contributes (pdf) to extremism.

- Overconfident people don���t just misperceive their own abilities. They also misperceive the world. They under-estimate the complexity of social phenomena and the boundedness of their rationality and knowledge. This leads to terrible decisions, such as Blair���s war in Iraq or Cameron���s belief that he could win the EU referendum.

Theresa May���s endless talk of ���strong and stable��� leadership fits this pattern. Of course, it poses the question: is she really strong or is this yet another example of overconfidence? Dogmatism and inflexibility are not the same as strength. Often, people boast of qualities they are unsure of: truly intelligent people don���t brag about their intellect, nor kind ones of their kindness.

Ms May hopes the voters won���t ask this question. And the evidence suggests that, sadly, she is right to do so.

April 28, 2017

Brexit: the egocentric framing error

Chris Grey decries the stupidity of Brexiters:

So insular has the discussion in the UK been before and since the referendum that one might think that Brexit is simply a matter of the UK formulating its demands.

What���s going on here is a specific example of a more general error. It���s what David Navon has called egocentric framing ��� a tendency to see problems only from our own point of view rather than to put ourselves into others��� shoes.

We���ve all been stuck in traffic on a motorway and changed lanes only to see a few minutes later than the lane we left is moving faster. The mistake we make in those cases is to forget that other drivers are trying to solve the same problem as us with the same evidence and so make the same choices ��� thereby adding to congestion.

Investors make the same mistake. One of the best-attested stock market anomalies is the tendency for newly-floated shares to fall (pdf) in the months after being issued. A big reason for this is that buyers don���t put themselves into the seller���s position. They see what looks like an attractive business but fail to ask: if this company is so good, why is the man who knows most about it willing to sell? Simply asking that question would save people money.

The same thing is true in games. When I play chess, I find that I do better if I put myself into my opponent���s position, and ask: what moves is she planning? What weaknesses trouble her?

It���s common for intelligent people to regard Brexit negotiations as an exercise in game theory. And they���re right. But the essence of game theory is to think yourself into the position of the other party. That means doing the precise opposite of egocentric framing.

Doing so is doubly beneficial.

For one thing, it gives us insights into what the other party wants and what they are willing to trade. It leads to some of the principles set out by Fisher and Ury in Getting to Yes (pdf): separate the people from the problem; focus on interests not positions; and invent options for mutual gain.

For another, putting yourself into the other person���s shoes will lead you to act like him, or at least give off cues that you���re like him. This will lead to better results simply because people tend to be more generous to those who are like us in some way. Some researchers have found that waitresses who repeat customers��� words earn bigger tips (pdf) than others. And other experiments have found that mimicking (pdf) the body language of your interlocutor can improve the outcome of negotiations. As the authors of that latter study say:

Mimicking can be a highly effective tool in negotiations. Negotiators often leave considerable value on the table, mainly because they feel reluctant to share information with their opponent due to their fears of exploitation. Yet building trust and sharing information greatly increases the probability that a win���win outcome will be reached���Our research suggests that mimicking is one way to facilitate building trust and consequently, information sharing in a negotiation. By creating trust in and soliciting information from their opponents, mimickers bake bigger pies at the bargaining table, and consequently take a larger share of that pie for themselves.

But Brexiters are doing the exact opposite of this. Little Englanderism, the assertion of our specialness and the imbecilic antics of Johnson all serve to create a distance between us and the EU, when we should be seeking to minimize that distance. As Chris says, ���every screaming headline and every bellicose punch-drunk interview from a Brexiter politician damages us more.���

And here, my patience runs out. Yes, government is a tricky business in which mistakes are inevitable. But we���ve a vast body of research which warns us of those mistakes, and which should equip us to at least avoid the obvious errors. The Tories, however, don���t seem able to do even this. The idea that they are best able to negotiate Brexit is not obviously founded in evidence. There���s more to negotiating than making strident demands.

April 27, 2017

The non-cost of the triple lock

Brad DeLong used to run a series of posts asking ���why oh why can���t we have a better press corps?��� Coverage of the pensions triple lock reminds me of his lament, because in one respect it is flat wrong.

The Guardian and the Independent agree that it is ���expensive.���

Wrong, wrong, wrong.

The minor problem is that it the triple lock doesn���t matter in the short-term. if inflation is over 2.5% - which is likely this year and possible next ��� the triple lock adds nothing that bog-standard uprating won���t. The FT wins a spotter���s badge for this:

The triple lock only becomes a bigger burden on the economy and public finances when the highest of prices, earnings or 2.5 per cent is greater than the growth in the absolute size of the economy.

Even this, though, is wrong. The lock will not be a ���burden on the economy.��� It is not a cost. It is a transfer from one group to another. As I���ve complained before, a transfer is NOT the same as a cost*. The pretence that it is serves a reactionary function as it creates the impression that the state is a burden when it is (often) not.

You might object that the transfer is a cost to the young. No. Most young people will become old and thus will get a state pension. The triple lock is therefore a transfer from us to our future selves. And it is our future selves that will benefit more than today���s pensioners. If the triple lock remains place, young people will benefit from decades of compound growth, whereas today���s old folk will see only a few years of such growth before they die. As Albert Einstein said, ���the most powerful force in the universe is compound interest.���

In fact, from the point of view of young people, it���s not clear that the triple lock is a cost even today. We must provide for a pension income somehow. The question is: do we do so via the state or via private pensions? And there is, as I���ve said, a strong case for doing so more via the state. Not only is it better placed to bear risk, but it is also cheaper: the charges on some private pensions can be pretty close to legalized theft.

We should think of the triple lock not just as part of fiscal policy but as part of pensions policy. From this perspective, it makes sense. Even for youngsters, it���s a saving insofar as it reduces the need to pay pension fund managers.

The triple lock, then, isn���t expensive**.

In saying this, I���m not just making an economic point. I���m also making a political one. Even when political journalists try to be neutral they are in fact biased. We, and they, should be more conscious of these biases.

* Actually, even in narrow fiscal terms, the triple lock isn���t that expensive. The OBR reckons that state spending on pensions will rise from 5.2% of GDP now to 7.1% by 2066-67 (table 3.7 of this pdf). This would leave spending lower than it is in many countries today: as the OECD says, UK state pensions are low relative to other rich nations. This is perfectly affordable, if we want it to be.

** Econ 101ers might object that pension provision via savings would increase the capital stock whereas provision via taxes wouldn���t. I doubt it. Even insofar as pension contributions go into the UK stock market, they only indirectly add to the capital stock simply because capital spending isn���t financed by issues of new equity. There are countless better ways of increasing the capital stock than by encouraging private pensions.

April 26, 2017

The demand for bastards

Earlier this week Michael Fallon warned that the Tories could use nuclear weapons as a pre-emptive measure. This is seen as evidence of ���strong leadership��� rather than the threat of a psychopathic war crime. At the same time, Labour���s promise of more Bank Holidays is presented as something fluffy and non-credible rather than as part of a plan to improve the UK���s terrible productivity.

Something odd is going on here.

The story of Juan Carlos Enriquez tells us what. He was ripped off by Donald Trump, and it took years to get his money back. But he voted for Trump.

What we see here is that there���s a demand for bastards. Being a dishonest psychopathic bully isn���t a disqualification, but a sought-after trait.

I���m not thinking here of the fact that many people prefer the unpleasant but competent boss to the nice but ineffective one. What I have in mind instead is that people interpret nastiness as a sign of competence. Nasty=tough=effective, at least when the nastiness is towards migrants or benefit recipients rather than to (perish the thought) bosses.

It���s not just in politics that this happens: boardrooms are stuffed with narcissists and psychopaths.

What���s going on here is a cluster of mechanisms. One is a form of wishful thinking. Just as people want to believe lies, so they want to believe a strong person can transform companies and societies.

Another is a fallacious form of the halo effect. People infer from the clich�� that Mussolini made the trains run on time that you have to be like Mussolini in order to make the trains run on time. This is not necessarily true.

Another is that we mistake overconfidence for actual ability. We thus imbue the confident narcissist or tough talker with talents which he doesn���t actually possess.

A third is a tendency to under-rate emergence and bounded rationality and knowledge. This leads to a demand for ���strong��� leaders and a dismissal of uncertainty as weakness rather than what it is ��� a recognition of our complex world and limited cognition.

In her endless talk of contrasting here ���strong leadership��� to the weakness and chaos of Corbyn, Theresa May is of course exploiting all these tendencies.

There���s just one problem here. It���s often wrong*.

George Osborne tried this trick. He wibbled about ���tough choices��� which mediamacro interpreted as evidence of strength and competence. But of course, it wasn���t: the government borrowed ��52bn in 2016-17, ��31bn more than the OBR forecast in 2012, which means austerity failed in its own terms. It was pure vandalism.

And Fred Goodwin was a tough and ruthless leader at RBS, but also one of the most catastrophic bosses in history.

Sometimes, bastards are just stupid bastards.

As Archie Brown has shown, the desire for strong leaders is often erroneous:

Popular opinion about whether a leader is strong or weak in the sense of being a dominating or domineering decision-maker can be extraordinarily wide of the mark���There is no reason to suppose that the ���strength��� of a prime minister���s leadership (in the sense of a domineering relationship with Cabinet colleagues) leads to successful government (The Myth of the Strong Leader, p 120)

In a complex society, decentralization and ���weak��� leadership might work better. As Clement Attlee said: ���The foundation of democratic liberty is a willingness to believe that other people may perhaps be wiser than oneself.���

All of which leads me to agree with George Monbiot: ���After 38 years of shrill certainties presented as strength, Britain could do with some hesitation and self-doubt from a prime minister.���

* But not always: one defect of agreeable people is that they can agree to the wrong things.

April 25, 2017

Beyond redistributive tax

Is there an egalitarian argument against sharply progressive income tax? I���m prompted to ask by John McDonnell���s plan to raise tax those earning more than ��70,000.

From the point of view of raising revenue, he���s bang right to target these rather than the mega-rich. For one thing, there���s more of them. And for another, they are a slow-moving target. Whereas a multi-millionaire hedge fund manager might react to higher taxes by retiring, downshifting, emigrating or fiddling the books, middle managers and head teachers have much less wiggle room. Optimal taxation theory thus says we should target them.

And Ben Chu is dead right to say that people earning over ��70,000 a year are rich - they���re in the top 5% of earners ��� and that denying this fact tends to serve the interests of the really rich.

There is, though, a problem here. People on higher incomes aren���t happier than others. In fact, ONS research (pdf) shows that those in higher income deciles are actually less happy (albeit not statistically significantly so) than those on middle incomes.

Yes, they enjoy higher life satisfaction and a sense of worth than others. And yes, net financial wealth more strongly correlated with subjective well-being. But higher earners aren���t happier than middling earners.

There are two reasons for this. One is that the richer you are, the more options you have, and so you���ll feel more regret about what you���re missing.

Another was pointed out by Adam Smith. It���s that high wages are often offset by other disadvantages, such as the disagreeableness of the work. Headteachers and middle managers are often stressed out; bankers and lawyers work stupid hours in unfulfilling jobs; and successful people, especially the minority who come from poor backgrounds, often suffer from imposter syndrome or a sense of alienation.

Yes, some lefties might think I���m bringing bring out the world���s smallest violin here ��� but that just shows a narcissistic lack of empathy. I���ve tried earning big wages. And it���s pretty unpleasant.

From a welfare egalitarian point of view, big taxes on high incomes aren���t altogether satisfactory.

In saying all this, I���m not merely parroting right-wing clich��s against taxation. For one thing, the same data that tell us that high income earners aren���t happy also tell us that the poor are unhappier, more anxious and less satisfied with their lives than the average earner. This is an argument for redistribution ��� or at least for paying more heed to the mental health of the worst-off. And for another, there might well come a time when higher spending on schools and education requires higher taxes rather than more borrowing.

Instead, I���m questioning here whether income is the right base for taxation. I suspect instead that ��� at least in efficiency terms ��� there���s a case for shifting the burden onto land. (Yes, Tim���s right that the UK taxes property more than most countries, but we don���t do so terribly efficiently or equitably).

But there���s a bigger point I���m making. There must be much more to leftist thinking than redistributive tax. In particular, what matters is inequalities of power and autonomy. The tyrannical boss oppressing his staff might not be far up the income distribution, but he���s well up the power ladder. That matters. And one reason why many of the rich ��� yes, the 95th percentile is rich ��� don���t feel good is that they lack power and autonomy, in part because of the conquest by managerialism over professionalism and craft skills.

For me, proper leftist politics would speak to these issues ��� and in doing so create a common interest between many of the financially well-off and the worst off. Traditional social democracy, however, has failed in this regard.

Another thing. I���ve never been happy with the utilitarian argument for higher taxes on the rich ��� that diminishing marginal utility means a rich man values ��1 less than the poor one. The rich are different people than the poor, so we can���t so easily compare marginal utilities.

April 23, 2017

Bank holidays & productivity

Labour wants us to have more bank holidays. There might be a good economic case for this.

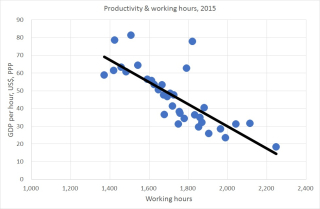

My chart hints at the point. It shows that, across 35 OECD nations, there is a very strong negative correlation (of minus 0.77) between annual working hours and GDP per hour worked. Countries that work less are more productive. The French, for example, are far more productive than the UK even though they spend all their time eating cheese.

The same correlation exists over time. We work only around half as much now as we did in the 19th century, but we���re far more productive in those hours we do work.

Of course, correlation is not causality. A big reason for this relationship is that more productive societies use their greater wealth to take more leisure.

But this might not be the whole story. It could be that the imposition of shorter working hours can help to spur productivity. Parkinson���s law tells us this. It says that work expands so as to fill the time available for its completion. If a manager knows that he has a long week to fill an order, he���ll take that long week. A shorter week could sharpen his incentives to increase efficiency.

Also, if people are working longer they get tired and jaded and so less efficient. A recent study of call centre workers has found that productivity falls as working hours rise even for people working quite short hours. This corroborates evidence from a very different industry ��� British munitions workers (pdf) during World War I. John Pencavel writes:

Employees at work for a long time may experience fatigue or stress that not only reduces his or her productivity but also increases the probability of errors, accidents, and sickness that impose costs on the employer���Restrictions on working hours ��� those imposed by statute or those induced by setting penalty rates of pay for hours worked beyond a threshold or those embodied in collective bargaining agreements ��� may be viewed not as damaging restraints on management but as an enlightened form of improving workplace efficiency and welfare.

France���s imposition of a 35-hour working week, for example, did seem to lead to a boost to productivity.

Of course, more bank holidays alone won���t close the massive productivity gap between the UK and other countries. But they might be one of many policies that might help.

There is, equally, a very long tradition of denying this. Nassau Senior opposed the 19th century Factory Acts limiting working hours because he believed that profits were made in the last hour. He was plain wrong (pdf). Mightn���t his 21st century counterparts also be mistaken?

It depends upon your view of British bosses. If you think they���re clueless inflexible buffoons, then there���ll not be a boost to productivity, because they won���t be able to rejig working methods sufficiently. If, however, you think they are smart enough to justify their big wages and egos, you���ll be more confident. From this perspective, it���s the right who should be more welcoming of Labour���s proposals than the left.

So why aren���t they? It���s because to them, managerial control is a good thing in itself.

Herein, though, lies the radical question posed by Labour���s proposal: should the job of increasing productivity ��� which should be our top economic priority ��� be entrusted wholly to managers, or is there instead a case for intervention by the state and (in different respects) workers? Even if Labour is wrong, it is at least asking a good question.

Chris Dillow's Blog

- Chris Dillow's profile

- 2 followers