Chris Dillow's Blog, page 79

July 5, 2016

Inequality, trust & politics

Nick Cohen and Gillian Tett are both worried about declining trust. Nick fears that ���a referendum that was meant to let ���the people take control��� and ���restore trust��� will have achieved the opposite.��� And Gillian writes:

we are moving from a system based around vertical axes of trust, where we trust people who seem to have more authority than we do, to one predicated on horizontal axes of trust: we take advice from our peer group.

There���s something important missing here ��� inequality. We have good evidence that increasing inequality leads to lower trust. As Mitchell Brown and Eric Uslaner write (pdf):

Declines in trust stem from economic inequality. As economic inequality increases, people feel that they have less in common with others, and therefore trust less.

The idea here is simple. As Alberto Alesina and Eliana La Ferrara say, ���individuals trust those more similar to themselves���. In unequal societies, however, rulers and experts are less similar to laymen, and so are less trusted*. This might be magnified by the outgroup homogeneity bias. Readers of this blog might be well aware of the big differences between, say, Ed Miliband and David Cameron, but to someone living in poverty in Hull they are both posh Oxford types.

As we���re seeing, this distrust has important effects upon political culture. For one thing, as Gillian says, it leads to a groupthink in which every tribe builds its own reality. Also, it erodes representative democracy. One reason why we had a referendum on the EU was that many voters didn���t trust MPs to take the decision for them. There���s a third thing, pointed out by James Coleman:

There seems to be extensive evidence that the rise of a charismatic leader���is likely to occur in a period when trust or legitimacy has been extensively withdrawn from existing social institutions. (Foundations of Social Theory p196)

The popularity of Nigel Farage fits this pattern**: we should worry that the gap left by his retirement will be filled by someone even worse.

All these processes are exacerbated by a weak economy, because as Ben Friedman has shown, economic stagnation fuels intolerance and closed-mindedness.

The point here is a simple one. The costs of inequality are not merely economic or social ones. They are also political: inequality leads to poorer political decision-making.

* The inequality that matters in this context might be more complex than simple Gini coefficients, being some mix of immobility, top income shares and an atmosphere of social distance and unequal respect.

** It���s worth asking how a privately-educated commodities trader who doesn���t listen to music, watch TV or read should have become regarded as a man of the people.

Another thing: you might object that the vote to leave the EU was the right one. However, in a good polity, the right decisions get made for the right reasons. This cannot be said of a campaign which was dominated by lies, racism and crass anti-intellectualism.

July 4, 2016

On state capacity

The news that the government might need to hire hundreds of immigrants to negotiate post-Brexit trade deals isn���t merely a delightful irony. It raises a serious question about the UK���s state capacity.

This refers (pdf) to the ability of governments to implement policies to achieve their objectives. Although it is usually discussed (pdf) in the context of less developed nations, it applies to the UK government now. Does it have the capacity to negotiate difficult trade deals, or to implement complex points-based immigration controls? The fact that we lack people capable of doing the former suggests perhaps not.

In fact, other things should strengthen our scepticism on this point. Larry Summers once wrote that "it is much easier to design policy than to implement it." The British government���s failure to introduce Universal Credit in a timely or cost-effective manner, and its mismanagement of the deportation of foreign students (in the ���safe pair of hands��� of Theresa May) give us two examples of this fact.

These, though, might be just specific manifestations of general defects. Christopher Hood and Ruth Dixon have shown (pdf) how the endless management reforms of the last 30 years have given us a civil service which ���worked a bit worse and cost a bit more��� than before. Giles Wilkes has written:

Much of the time, Whitehall throngs with officials struggling just to find out what is going on. The sound of dysfunction is not the cacophony of argument, but the silence of suppressed documents and unreturned phone calls.

And a report from the Institute for Government says:

Departments are inconsistent in how they format and organise their objectives. They confuse measures, milestones and means of reaching them. The inconsistency across departments and the sheer number of objectives questions how useful and usable they are ��� and crucially, whether they are actually being used to measure performance.

This suggests that government is failing to implement the Bloom and Van Reenen idea that management is a form of technology (pdf), in which there are clear targets, monitoring and feedback.

It is appropriate that I should be writing this in the week that the Chilcott report is finally published. Its massive delays remind us that complex tasks often take much longer than expected, in part because of the planning fallacy.

All this should add to our scepticism about whether Brexit can proceed smoothly, even ignoring (which we shouldn���t) the legal technicalities and arguments. I fear that Brexiteers��� optimism on this point reflects what I���ve called cargo cult leadership: the ���right leader-????-success��� fallacy.

And herein lies another delightful irony. Many right-wingers have for years preached the virtues of small government and been sceptical of what the state can achieve. And yet it is now they who are placing massive and perhaps excessive demands upon the competence of the state.

July 3, 2016

Cognitive biases, ideology & control

Yesterday, I spoke at a symposium in honour of Andrew Glyn. This is the gist of what I said.

We economists ��� especially those of us who are on the left - have got a problem: voters don���t agree with us.

Events a few days ago demonstrated this. But it is in fact a longstanding issue. For years, and around the world, voters have had attitudes opposed to ours. They have been more hostile to immigrants and benefit claimants and more supportive of austerity and inequality than we would like. (This isn���t just an issue for the left: voters also have anti-free market attitudes.)

Why is this? I want to suggest that it is because Marxists were right all along. It���s because capitalism generates an ideology which opposes sensible radical reform. The idea of false consciousness should be taken a lot more seriously.

I came to this view via an apparently circuitous route. In my brief and ignominious career in finance, I learned about behavioural finance. This field, inspire by Daniel Kahneman���s work on cognitive biases, is the idea that people make small but systematic errors of judgment when managing their money.

But this raises a question. If people are subject to cognitive biases when they have big incentives to be right ��� when they are investing their own money ��� mightn���t the same be true in politics, where their incentives are less sharp?

Some experimental research suggests the answer is: yes.

Some of these experiments have been done by Kris-Stella Trump at Harvard. She split money between subjects in different ways and then asked them what they thought would have been a fair division. She found that those who got a very unequal split thought that the fair division should also have been unequal. Those who got a more equal division said that a fair division would have been equal.

This suggests that as inequality increases, our perception of what���s fair becomes more unequal. That causes people to accept inequality. This is an example of a wider cognitive bias ��� the anchoring effect.

We���ve seen this in the real world. Back in 1995, there were protests against the ���fat cat��� salary received by Cedric Brown at British Gas. By today���s standards, that salary was very low - just over ��2m, compared to an average FTSE 100 CEO pay of almost ��5m. And yet protests against high pay are no greater now than then. We���ve come to accept greater inequality, just as Dr Trump���s work implies.

I���ll give you some more experiments. These were done (pdf) by Phillip Grossman and Mana Komai at Monash University. They generated increasing inequality between laboratory subjects and then gave people the option of paying to destroy some others��� wealth. They found that many took up the offer. But it wasn���t only the wealth of the rich they destroyed. Almost as often, the poor attacked the poor.

What���s going on here is a concern for relative status. People try to preserve their self-image by holding others down. This is entirely consistent with attacks upon immigrants and benefit claimants.

Here���s another example: wishful thinking, or the optimism bias. John Steinbeck once said that there���s no socialism in the US because the poor think of themselves as temporarily embarrassed millionaires.

A similar thing happened here in the 2015 election. The Tories said they���d cut welfare benefits. What voters heard was benefit cuts for other people.

Again, we���ve got laboratory evidence for this bias. Experiments by Guy Mayraz have shown that it���s incredibly easy to induce wishful thinking in people.

I could go on. There���s the just world illusion, status quo bias and adaptive preferences. Put all these together and you have what John Jost calls system justification theory (pdf) ��� a set of ideas that sustains inequality and injustice.

All of this helps explain why there isn���t more hostility to inequality. But it doesn���t explain why anger at elites was channelled towards voting for Brexit rather than into more economically sensible directions.

I suspect three mechanisms helped here. One was wishful thinking.

Another is prospect theory. This tells us that people who feel they���ve lost want to gamble to break even. This is why they back longshots on the last race of the day or why they hold onto badly performing stocks. The thing motivated many Leavers. People who had lost out from globalization, or felt discomfited by immigration, voted Leave because they felt they had little to lose from doing so.

The third mechanism has been discovered recently by David Leiser and Zeev Kril. They show that laypeople���s thinking about economics is dominated by what they call the ���good begets good��� heuristic. People believe that good things have good effects.

This, I suspect, explains a lot. People think controlling the public finances, or controlling immigration, are good things, so they must have good effects. I shouldn���t need to tell you that it ain���t so. In this context, the slogan ���Vote Leave, Take Control��� was an act of genius. It appealed to the ���good begets good heuristic as well as to the fact that people facing uncertainty and feeling distrustful of elites want more control for themselves. (Perhaps this is fuelled by yet another cognitive bias - overconfidence about the benefits of such control)

I contend, therefore, that Marxian theories of ideology are supported by recent research. People aren���t just misinformed about political issues ��� there���s lots of surveys telling us that. They are irrational too. They have false consciousness.

Now, this goes against mainstream centrist thinking, which seems to have imported into politics a theory of consumer sovereignty just as behavioural economics is undermining that theory. But it is in fact an old idea. We���ve known since the work of Richard Downs in 1955 that people can be rationally ignorant about politics. We also know they can be rationally inattentive. So why can���t they also be rationally irrational in politics?

All this poses the question: what can be done about this? The answer isn���t to dismiss people as stupid. The point about the cognitive biases programme is that it shows that we are all prone to error. In fact, this is true of those of us who are awake to such biases. Once you start looking for such biases, you see them everywhere ��� and perhaps exaggerate their significance. That���s an example of the confirmation bias.

Instead, we should think about policies that run with the grain of people���s biases and yet are sensible themselves. One clue here lies in that word ���control���. What we saw during the EU referendum is that people want control. We should therefore offer voters just this. And meaningful control, not just immigration controls.

I���ll leave others to think about what such a platform might be: for me, it includes a citizens income and worker democracy among other things. The point, though, is that whilst we hear much about inequalities of income, the left must also think about reducing inequalities of power.

June 30, 2016

Control: beyond left and right

In a typically brilliant essay Will Davies writes:

The slogan ���take back control��� was a piece of political genius. It worked on every level between the macroeconomic and the psychoanalytic���What was so clever about the language of the Leave campaign was that it spoke directly to this feeling of inadequacy and embarrassment, then promised to eradicate it. The promise had nothing to do with economics or policy, but everything to do with the psychological allure of autonomy and self-respect. Farage���s political strategy was to take seriously communities who���d otherwise been taken for granted for much of the past 50 years.

This point broadens. Consider some popular political positions. There���s support for immigration controls and fiscal austerity on the one hand but also for nationalization and even price controls on the other: one Yougov poll found (pdf) that 45% of people favour rent controls and 35% even controls on food prices.

These positions make no sense if you think in terms of left and right. But they become perfectly consistent once you see that people want things to be controlled: the popularity of austerity, I suspect, arises from the view that the public finances are ���out of control.���

This demand for control is, if not the sigh of the oppressed, then the sigh of the insecure. When faced with uncertainty ��� not just about their economic lives but about cultural change too ��� people want a sense of control.

Of course, mainstream economists will see a flaw in these demands. The economy is a complex process which can���t necessarily be controlled for the better. Attempts to control immigration and the public finances have well-known costs. What we���re seeing here is an example of what David Leiser and Zeev Krill call the ���good begets good��� heuristic. People think control is a good thing and must therefore have good effects. But it ain���t necessarily so.

Herein, however, lies a massive opportunity for the left. We should be offering solutions to uncertainty ��� a stronger better social safety net and a job guarantee. We should also be offering people real control over their lives ��� and not control exercised on their behalf by the sort of elites they profess to despise.

This sort of platform should be able to unite the left and right of the Labour party ��� or at least it might insofar as that division is founded in ideas rather than personal animosities. From the right, it means developing the sort of community politics advocated by Liz Kendall:

We���ve got to start giving people a say and a stake in the decisions that impact their lives. And that starts in our communities, sharing power rather than just hoarding in in Whitehall or the Town Hall.

On housing, health, unemployment and a range of other areas, we have to trust the British people, and understand that those who know what is needed in their local area are the people who live there.

And from the left, it means expanding worker democracy, as advocated by John McDonnell.

I���d add that there���s one policy which might both improve the social safety net, thus reducing insecurity, and increase people���s control over their own lives by offering them what Philippe Van Parijs calls (pdf) ���real freedom��� ��� a citizens��� income.

This might be an argument for another day. My broader point is simple. If we can ditch tribalism about left and right and think about how some good economic policies can fit in with people���s demands for control over their lives, the Labour party might just have a bright future.

June 29, 2016

Demystifying leaders

The search for a new England manager, new Tory leader and perhaps new Labour leader too brings an under-appreciated question into focus: what exactly can leadership achieve?

In the Times today, Matthew Syed decries the ���ludicrous idea that everything would be well if only we could find a new messiah.��� He���s talking about the England manager���s job, but the words fit a lot of people���s attitudes to the Labour leadership: Tories, I sense, are slightly more sensible.

This messiah complex is what I���ve called cargo cult thinking, the sort of thing that goes like this:

Leadership

?????

Success.

People don���t fill in the ?????. They assume that the new messiah will perform some ju-ju and success will follow. They don���t ask the question which the late great Andrew Glyn drummed into us: what���s the mechanism?

I���d suggest three broad correctives to this messiah syndrome.

First, remember that what matters is the match, not just the man. Compare Louis van Gaal and Claudio Ranieri. Two years ago, van Gaal had by far the more impressive CV, with league titles in three countries and a Champions League medal. But Ranieri was a glorious success at Leicester whilst van Gaal suffered at Manyoo. The reason? Ranieri turned out to be a great match with City���s squad, whilst van Gaal never fitted in.

The point generalizes. Boris Groysberg studied the fortunes of managers who moved from GM ��� generally regarded as a great training ground for bosses ��� to other firms. He found (pdf) that where the manager was a good fit for the new company he did well but where he wasn���t, the firm suffered. This is despite the managers appearing equally competent beforehand. For example, if a firm needs to cut costs it shouldn���t hire a marketing man, but if it needs to manage expansion it shouldn���t hire an axeman. As the clich�� goes, you need round pegs in round holes.

When we���re looking for a leader, we must ask: what exactly is the defect we are trying to address? For England manager, it seems to be a need to overcome the mental block that so often strikes players in big tournaments - what Vincent Kompany calls the ���psychological event��� that afflicted the team against Iceland.

For Labour, I���d contend, it is a need to unite the PLP and grassroots. This requires emollience, charisma and person-management skills rather than a talent for policy development, because in the economic sphere at least this has been going well.

Whether such good matches are discovered by skilful hiring or by dumb luck is another question.

Secondly, we must remember that, as Nick Bloom and colleagues say, management is a technology (pdf). Those ????? are processes whereby performance is monitored and feedback gathered to enable the aggregation of marginal gains. We should ask of leaders: what processes have you put in place to facilitate improvement? It could be that the best such processes require less "strong leadership" and more decentralized or collegiate decision-making - although such a view is outside the Overton window.

The third principle is to be aware of the force for good and ill of organizational capital. Some organizations are so structurally weak that pretty much no manager can turn them around. As Warren Buffett said:

When a management with a reputation for brilliance tackles a business with a reputation for bad economics, it is the reputation of the business that remains intact.

This could well be England���s problem. Fifty years of hurt under all different types of boss hint at deep structural problems; Matthew is right to say that it is the system that has failed. The same might be true of any Labour leader. Given the hostile ideological climate, (alleged?) splits between social conservatives and metropolitan liberals and a declining class base, it might be that nobody can be a truly successful leader now.

You might think this is a post about leadership. It���s not. It���s about inequality. Matthew says that it���s no coincidence that Roy Hodgson was paid more than any other manager at the European finals. He's right. High pay for bosses arises from the messiah complex we have about them ��� from the superstitious nonsense that the best man will put everything right. Perhaps demystifying management and leadership would be one small step towards more sensible levels of pay and hence towards less inequality.

June 28, 2016

Austerity and racism

The costs of fiscal austerity, and of this wretched government���s incompetence, are vastly higher than even its critics appreciate.

I say this because of a new paper by Markus Brueckner and Hans Peter Gruener which shows that ���lower growth rates are associated with a significant increase in right-wing extremism.��� This corroborates a point made by Ben Friedman back in 2005:

The history of each of the large Western democracies ��� America, Britain, France and Germany ��� is replete with instances in which [a] turn away from openness and tolerance, and often the weakening of democratic political institutions, followed in the wake of economic stagnation that diminished people���s confidence in a better future. (The Moral Consequences of Economic Growth, p8-9)

And let���s be clear. Stagnation is just what millions of people have suffered. The Resolution Foundation reports that over half of working age households have seen flat or falling living standards since 2002. This created a discontent with the establishment that manifested itself in support for Brexit. As Torsten Bell points out, there's a strong correlation between wage levels and the tendency to support Brexit, which suggests that if the economy had done better and wages (especially those of the worse off) were higher, there'd be less support for Brexit. Basic behavioural economics ��� prospect theory ��� tells us that people who feel they���ve lost will be tempted to take reckless gambles.

Of course, austerity isn���t the sole cause of low incomes: even a decent government would have struggled against the post-crisis stagnation in productivity and growth. But austerity undoubtedly exacerbated the problem.

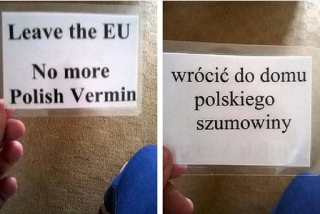

And of course, support for Brexit, in itself, is not right-wing extremism. But as Aditya Chakrabortty says, the campaign helped to generate racism. Discontent with stagnant real wages and poor public services ��� both the result of austerity ��� led to a demand for Brexit which itself fuelled a surge in racism. The cost of austerity isn���t just lost GDP. It���s is increased intolerance too. There���s a direct link from Osborne���s criminal economic mismanagement to hate crimes.

You might think I'm going too far here. I'm not. In fact, this is basic economics. Econ 101 says that people respond to incentives. And the incentive to express racist opinions rather than keep them bottled up has increased recently because when politicians express neo-racist ideas, people believe that the stigma attached to being racist has declined. In this sense, the cost of being a low-level racist has fallen - and a fall in costs generates increased supply.

Granted, Cameron and Osborne sincerely deplore such attacks. But that misses the point ��� that if you dump a pile of shit on your doorstep, you can���t disown the flies.

It���s not surprising that this link is under-appreciated. For one thing, people are lousy at making connections in the social sciences. For another, deference, ideology and tribalism mean that even the worst politicians retain support; a quarter of Americans thought Richard Nixon was doing a good job as US president even at the peak of the Watergate scandal. These forces are, of course, reinforced by our terrible media. On the Today programme Nick Robinson asked Osborne whether the government was right to call a referendum. But he didn���t ask whether austerity and stagnation had increased support for Brexit ��� perhaps because mediamacro ideology blinds the BBC to such possibilities.

But let���s be clear. Osborne and Cameron haven���t merely wrecked Britain���s reputation in the world, cost us billions of pounds in lower real incomes and driven people to despair and suicide. They have now created a climate in which migrants and ethnic minorities no longer feel safe. Has there ever in our history been a more abject, incompetent, stupid, reckless, contemptible government than this?

June 26, 2016

The BBC problem

Among the many people and organizations to have had a bad referendum campaign, one has so far gone under-remarked: the BBC. The campaign has highlighted profound inadequacies in its current affairs reporting. I mean this in three ways.

First, in being impartial between truth and lies, the BBC was complicit in a conspiracy to defraud the public. Its more intelligent correspondents are aware of this. Here���s assistant political editor Norman Smith (7���52��� in):

There is an instinctive bias within the BBC towards impartiality to the exclusion sometimes of making judgment calls that we can and should make. We are very very cautious about saying something is factually wrong and I think as an organization we could be more muscular about it. I���ll give you an example, which is one that cropped up, and there was a lot of debate within the BBC about it, was when the Brexit campaign suggested that Turkey was poised to join the EU, and that there was nothing we could do about it. Now that is factually wrong, but when we initially covered the story, I think we said along the lines of ���Remain had said that is wrong��� ��� in other words, we attributed the assessment to the Remain side, when we could, of our own, say ���No, that is factually wrong.��� But, because as an organisation, more than any other organisation, there is a massive pressure and premium on fairness, on balance, on impartiality, I suspect we, we hold back from making those sort of calls, and I do think that, potentially, is a disservice to the listener and viewer.

Secondly, the BBC���s main new coverage was guilty of adverse selection. As Simon says, there were two campaigns: a reasonable and civilized one; and a bitter dishonest one. The BBC gave us too much of the latter. On the Leave side, we heard too much from liars and crypto-fascists and too little from more decent Brexiters. And on the Remain side, it gave us too much of the exaggerations of Cameron and Osborne and too few more sober voices.

Thirdly, and perhaps relatedly, many of the BBC���s main current affairs programmes forget the first two of Lord Reith���s trilogy ��� inform, educate and entertain ��� in favour of the latter. Nick���s right:

The worst journalists, editors and broadcasters know their audiences want entertainment, not expertise. If you doubt me, ask when you last saw panellists on Question Time who knew what they were talking about.

In these ways, the BBC is a major culprit in the degradation of our political culture. It is heavily responsible for the fact that voters were wrong about key facts in this referendum.

Worse still, it breaches its own principles of impartiality. These failings give undue prominence and hence power to those who can play its game ��� to overconfident entertainers with simplistic slogans rather than to more honest voices who acknowledge the complexity of the world*. This is a bias, and a nasty one.

In its defence the BBC can point to More or Less and Reality Check as evidence that it can do a good job. True. I���d go further. Much of what the BBC does outside of its new coverage makes it one of our great national treasures. But this only sharpens the contrast with the fact that its main political and economic coverage, not just in the referendum, is fraudulent and philistine.

Herein, though, lies a problem. Anyone who points this out risks being accused of bias themselves or of being a sore loser (though note that I was making similar points when Remain was expected to win). And it must be admitted that many of those who accuse the BBC of bias are green-ink writers moaning that the corporation doesn���t echo their own neuroses ��� a fact which BBC management uses to deflect attention from its genuine failings.

This poses the question: what can be done? I���m pleased to see that Open Democracy is thinking about these issues. Possible solutions include:

- Scrap the due impartiality requirement, and instead allow a multiplicity of voices. This, though, brings problems. It would mean admitting racists onto the airwaves, or (alternatively) there���s a danger of insufficient diversity: Marxist libertarians, true conservatives, small-state Keynesians and suchlike won���t get as much publicity as they should.

- Abolish political correspondents and replace them with specialist reporters with a good background in their beat: I suspect it���s easier to teach broadcast techniques to an expert than expertise to a journalist.

- Have an alternative vision of the BBC. It should be a promoter of the liberal arts ��� of the best that has been thought and said, and is being thought and said. This requires that it move far up-market, giving less coverage to rentagobs and more to civilized minds. The BBC should employ philosophy and sociology reporters, not political ones.

I���d like to think that pressure on the BBC to move in this directions would be bipartisan, coming from anyone who cares about our country���s intellectual life. Given that its trash journalism serves reactionary charlatans well, however, I fear that such a hope is a forlorn one.

* This might contribute to a class bias, insofar as it favours those whose private education imparted a glossy self-confidence.

June 25, 2016

In defence of Corbyn

The proposed vote of no-confidence in Jeremy Corbyn worries me: I fear it is based in part upon three motives that are wrong, one of which is plain vicious.

The first of these wrong motives is that Mr Corbyn was only half-hearted in campaigning for Remain. In fact, his giving the EU a seven out of ten was a rare light of honesty in a campaign dominated by lies and exaggerations. The EU���s treatment of Greece, and its tolerance of mass unemployment, testify to the organization���s flaws: Andrew Lilico is right to say it must be reformed radically.

The second motive ��� expressed by Frank Field on the Today programme ��� is that Mr Corbyn in not a ���credible��� Prime Minister. He says: ���We clearly need somebody who the public think of as an alternative prime minister."

Now, this statement comes at a time when Boris Johnson is odds-on favourite to be next Prime Minister. The fact that a liar, charlatan and hypocrite can be regarded as a plausible PM shows that our political culture ��� fostered by the BBC ��� is deeply sick. Labour should be fighting this, not acting as Quislings for a feudalistic deference to the high-born.

My biggest problem, however, is that I fear that the desire to get rid of Corbyn is based in part upon a desire to ���listen��� to ���concerns��� about immigration ��� expressed by Mr Field this morning. As one rentagob put it*:

Labour has gone wrong by not being in touch with its voters. I���ve been saying this for the last 10 years in relation to immigration and free movement of labour.

This, of course, misses the facts. Immigration is not responsible for low wages, job insecurity and the difficulty of seeing a GP. Mr Corbyn is wholly correct to say that a large part of the solution to this is to have ���an alternative to austerity**.���

It could be that those who want to shift Labour towards greater hostility to immigrants want to use the Farage-Hannan trick of winning elections: lie your face off during the campaign and then disown your promises after you���ve won. This, however, is risky. For one thing, there���s a danger of getting high on your supply ��� of believing your own lies. And for another anti-immigration talk has real consequences: it stokes up hate and makes immigrants (and let���s be honest, British-born ethnic minorities too) less safe on the streets. That is utterly intolerable.

Now, I���ll concede that there might well be more reasonable motives for wanting Corbyn out: I���ve no beef with Nick���s complaints about his curious associates, and I fear there���s some merit in the allegations that his organization and campaigning skills are weak.

In throwing out this bathwater, however, Labour risks losing a beautiful baby. John McDonnell is building one of the best economic platforms a major political party has had in my lifetime. It would be a tragedy if this is lost in a retreat towards reaction and economic illiteracy.

* Insofar as this is a motive for hostility to Corbyn, it is wholly wrong to present the issue as one of Blairites versus the Left. For all their flaws, Blairites were ��� to their credit ��� not anti-immigrant.

** I���d add that this alternative should be at a pan-European level; a big reason why immigration is so high is that one-in-five under-25s in the euro area is out of work (pdf). Sadly, however, the UK has lost much of its influence to make this argument.

June 22, 2016

Beyond meritocracy

It���s time to ditch the idea of meritocracy. That���s the message of James Bloodworth���s excellent little book, The Myth of Meritocracy. He shows that Britain is far from being a meritocracy: the privately educated do far better than the state-educated; even within the state sector the best schools are in the most expensive areas; and in most professions nepotism, expensive qualifications and the need to do unpaid internships exclude bright people from poor backgrounds.

You don���t need academic research ��� what Michael Gove would no doubt call Nazism ��� to see this. The collapse of the banks in 2008 and the piss-poor level of political debate and journalism all show that the rich and successful don���t have much merit.

What���s more, says James, genuine meritocracy is impossible:

No government could equalize the quality of a child���s parenting even if it wanted to. Equality of opportunity is thus a utopian fantasy.

He might have added that meritocracy is, as Hayek pointed out, incompatible with a free market economy. A strictly meritocratic society would have to ban employers from hiring whom they wanted and ban activities such as reality TV shows or clickbait journalism in which unmeritorious people can succeed.

James is also right to question whether the fantasy of a meritocratic society would be just: ���should those who inherit low ability be condemned to a bleak and wretched life based on what is, in essence, the mere lottery of genetics?��� The principle of luck egalitarianism gives us an unequivocal answer: no.

Regular readers will know that I agree with all this. But I���d add something ��� that a meritocratic society isn���t even economically efficient.

Imagine will lived in a centrally planned economy which was, thanks to its lack of freedom, a pure meritocracy. The job of commissar of bread supply therefore goes to the best person for the job. Is this efficient?

Obviously not, because nobody, however meritorious, has sufficient skill to control and plan something as complex as bread production. The job of commissar of bread supply simply shouldn���t exist.

I suspect the same is true in our economy. The economic case for meritocracy is that the most demanding jobs must be done by the best people, those most able to do them. But what if these jobs are so demanding that nobody can reliably do them ��� that the span of control is so wide as to exceed anybody���s cognitive skills? In such cases, the solution isn���t meritocracy, but to deconstruct ���top jobs��� to make them less demanding. Diversity trumps ability. Ways of doing this might include: decentralizing management to make firms less dependent upon ���leaders���; using rules or automatic feedback processes rather than ���judgment���; simplifying organizations for example by breaking up banks; introducing proper institutions of deliberative democracy rather than relying upon politicians��� initiatives; and so on.

A less radical variant might be to recognize that when the occupant of a ���top job��� does well it is often due less to his own brilliance than to the quality of the match between his ability and the needs of the organization. Such a perspective would at least undermine the over-entitled claims of the successful that their ���talents��� be lavishly rewarded.

In saying all this, however, I am merely reinforcing James��� conclusion ��� that what matters is not the pursuit of an unattainable and repellent meritocracy but rather a more egalitarian society in which everyone can live well. Such a society requires not just the redistribution of income, but of power and respect too.

June 21, 2016

A conservative case for Remain

Whilst I was away, the nation celebrated the Queen���s 90th birthday. Nobody has noted that such celebrations suggest an under-appreciated conservative reason to vote Remain.

The point is that, in doing her job so well, the Queen has taken an issue off the political agenda ��� the question of whether we should have a monarchy at all. This is a great public service. People aren���t very good at thinking. We face what Thomas Homer-Dixon called an ingenuity gap ��� a gulf between our limited knowledge and rationality on the one hand and the complexity of society on the other. This gap means that it���s best that we think as little as possible about political issues and make do with the arrangements we have, even if these are imperfect. As Alfred North Whitehead said:

Civilization advances by extending the number of important operations which we can perform without thinking about them. Operations of thought are like cavalry charges in a battle ��� they are strictly limited in number, they require fresh horses, and must only be made at decisive moments.

Brexiteers, however, are doing the exact opposite of this. They are putting onto the agenda things that don���t need to be there. If we vote Leave, our politics will be dominated for years by political wrangling with the EU and with trade negotiations with the rest of the world. Philip Collins��� plea on twitter was a just one:

Please don't make me learn the difference between EEA & WTO rules for trade negotiation. Please, please don't do that.

Given the ingenuity gap, there can be no assurance that these will turn out well: Mr Gove���s claims to the contrary seem to me to owe more to that most ubiquitous of cognitive biases, overconfidence, than to hard reason. In fact, there���s a paradox here: Leavers scoff (rightly) at economists��� forecasting skills but fail to point out that forecasts fail because economies are so complex ��� and this same complexity is an argument for not disrupting trading rules unnecessarily thus creating uncertainty.

What���s more, with the cognitive bandwidth of our politicians limited, such issues will displace more important ones, such as how to tackle secular stagnation, the housing crisis, how to improve public services and the benefits system, and so on.

In saying this, I am echoing a Burkean scepticism about change. As Mark Mills has said, ���conservatism ought to abhor wrenching discontinuities like Brexit.��� He cites Jesse Norman on Edmund Burke:

The political leader knows in advance that all change, however well intentioned, will disrupt the social fabric, with unforeseeable and potentially serious negative consequences. Still more is this true of sweeping, radical change���For radical change to be genuinely worthwhile, it must bring overwhelming social benefit, or be the product of the most extreme necessity.

Unless you are a grotesque bigot, you cannot claim with any confidence that Brexit will bring overwhelming social benefit. Nor is there any ���extreme necessity��� ��� one of Whitehead���s ���decisive moments��� ��� why we should leave now. Yes, such a moment might occur in future ��� though nobody can tell ��� but for now we are rubbing along tolerably within the EU. We don���t therefore need to incur the massive cognitive cost of leaving.

From this perspective, Leavers are not conservatives. The kindest thing one can say about them is that they are radicals, but many of us would have less kind words.

There is, though, another point here, one I���ve made several times. It���s that one form of conservatism is largely lacking from our political discourse ��� a cool scepticism about rationality, perfectibility and top-down-driven social change. For me, this is a considerable loss.

Chris Dillow's Blog

- Chris Dillow's profile

- 2 followers