Chris Dillow's Blog, page 82

April 27, 2016

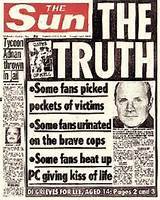

Hillsborough: the class context

The truth about Hillsborough has of course always been known. What happened yesterday was that it finally became incontrovertible. I fear, though, that the context of Hillsborough is in danger of being forgotten ��� that context being that the 1980s was an era of moral panic about the working class.

Back then, football fans were mostly working people. It cost only ��2 to get into a first division game in the mid-80s, and the influx of fashionable middle-class men talking about ���the footie��� was a post-Gazza, post-Hornby phenomenon. Such fans were the object of fear and contempt by the police and Tory party: Thatcher tried to impose ID cards onto them. Here���s how When Saturday Comes described the attitude towards fans then:

The police see us as a mass entity, fuelled by drink and a single-minded resolve to wreak havoc by destroying property and attacking one another with murderous intent. Containment and damage limitation is the core of the police strategy. Fans are treated with the utmost disrespect. We are herded, cajoled, pushed and corralled into cramped spaces, and expected to submit passively to every new indignity.

However, football fans were not the only object of class-based moral panic. Thatcher famously described miners as ���the enemy within���: not, note, people with mistaken ideas but an enemy, comparable to warmongering fascists. And there were panics about ���new age travellers��� and ���acid house���.

Now, there is ��� sad to say ��� an ugly truth here. These panics were not wholly unfounded. Crime was high in the 80s, and football hooliganism was a genuine problem; Heysel happened just four years before Hillsborough. However, a pound of fact became a ton of moral panic and class hatred.

It���s in this context that we should interpret the slanders against the Hillsborough victims by Tories such as Irvine Patnick, Bernard Ingham and Kelvin Mackenzie. Their fear and hatred of working people had reached such feverish heights that they were prepared to believe them capable of robbing the dead.

In all these cases, the police were brutal enforcers of this class-based hatred ��� and unlawfully so. After the battle of Stonehenge in 1985 Wiltshire Police were found guilty of ABH, false imprisonment and wrongful arrest. And after Orgreave South Yorkshire Police ��� them again ��� paid ��500,000 compensation for assault, unlawful arrest and malicious prosecution. As James Doran says:

The British state is not a neutral body which enforces the rule of law - it is a set of social relations which uphold the rule of the capital. Law is a matter of struggle - ordinary people are automatically subject to the discipline of the repressive apparatus of the state.

All this poses a question. Have things really changed? Of course, the police and Tories have much better PR than they did then. But is it really a coincidence that the police still turn up mob-handed to demos whilst giving a free ride to corporate crime and asset stripping? When the cameras are off and they are behind closed doors, do the police and Tories retain a vestige of their 1980s attitudes? When Alan Duncan spoke of those who aren���t rich as ���low achievers���, was that a minority view, or a reminder that the Tories haven���t really abandoned their class hatred?

Many younger lefties might have abandoned class in favour of the politics of micro-identities. For those of us shaped by the 80s, however, class matters. And I suspect this is as true for the Tories as it is for me.

April 26, 2016

On multipliers

Richard Murphy writes:

[The government and OBR] believe that austerity generates growth and so cuts the deficit. The trouble for them is that all the evidence shows that the opposite is true: cuts shrink national income and government spending increases it.

This has attracted cheap abuse from some of Tim Worstall���s commenters. Such abuse is wrong, and misses the point.

It���s wrong, because - in the context he is writing about ��� Richard is right to claim that fiscal multipliers are big. There���s widespread agreement (pdf) that multipliers are bigger in recessions (pdf) than in normal times. For example, Lawrence Christiano, Martin Eichenbaum, and Sergio Rebelo say (pdf):

The government-spending multiplier can be much larger than one when the zero lower bound on the nominal interest rate binds.

The fact that Osborne���s austerity has failed to cut the deficit as much as expected is wholly consistent with this. Bigger multipliers than Osborne assumed meant that austerity depressed output by more than he expected thus making it harder to reduce borrowing.

In this sense, Richard���s critics are plain wrong.

However, multipliers aren���t always big. They vary. As Olivier Blanchard and Daniel Leigh wrote (pdf) in the IMF's mea culpa:

There is no single multiplier for all times and all countries. Multipliers can be higher or lower across time and across economies.

One important factor here is the monetary offset. When interest rates are high fiscal austerity would reduce rates, perhaps causing an expansionary fiscal contraction. When interest rates are zero and central bankers are unable (or unwilling) to undertake offsetting monetary policy, fiscal multipliers will be larger.

It���s in this context that I say that Richard���s critics are missing the point. One beef I have with his piece is that na��ve readers might interpret his claim that multipliers are large not as a fact about the 2010-2015 period, but as a truth that holds all the time. This leads to the inference that a future Labour government should increase public spending considerably.

This, though, isn���t necessarily the case. If inflation is around its target, the Bank of England would respond to fiscal expansion by raising rates, resulting in a lower multiplier. This might or might not be a good thing ��� the appropriate fiscal-monetary policy mix is a legitimate matter of debate ��� but it would mean that the fiscal multiplier might be disappointingly small. (To put this another way, a fiscal expansion accompanied by an increase in the inflation target would have a bigger multiplier than one accompanied by retaining the 2% target.)

In this sense, advocates of a fiscal expansion after 2020 might be making the same error as advocates of expansionary fiscal contraction in 2010 ��� they are wrongly assuming that the same fiscal multiplier applies at all times. It doesn���t.

I���m making two points here, one about economics and one about politics. The economic point is to endorse what Dani Rodrik says in Economics Rules:

Different contexts ��� different markets, social settings, countries, time periods, and so on ��� require different models.

Economics is not like physics. In our discipline there are few if any reliable parameters.

The political point is that Labour supporters should not rely upon a big multiplier as a case for fiscal expansion. And not need they do so. Lots of leftist policies ��� such as tax and welfare reform or expanding worker ownership ��� can be designed without reliance upon fragile claims about the macroeconomy.

April 23, 2016

Why not full employment?

In a thought-provoking piece, Jeremy Gilbert writes:

Hardly anyone looks back to the epoch of full employment as one which seems remotely culturally attractive. We might entertain time-travel fantasies of visiting Harlem in the 20s, Haight-Ashbury in 1967, or Paris at various points in the 19th or 20th centuries ��� but who wishes they could spend a week in Surbiton, 1955?

This is also the question asked in a recent paper by Jon Wisman and Michael Cauvel: why do workers not demand guaranteed employment?

Three facts give the question force. One is that technocrats now know, more than they did in the 70s and 80s, that unemployment not only has an economic cost in terms of lost output, but a massive psychological cost because the unemployed are significantly unhappier than those in work. For example, the ONS estimate that whereas only 2.9 per cent of those in work have low life-satisfaction (0-4 on a 0-10 scale) 12.9 per cent of the unemployed do.

Secondly, there is a huge amount of unemployment and under-employment now even though the proportion of working age people in work is at a post-1971 high. On top of the 1.7m officially unemployed there are 2.2m people out of the labour force who���d like a job and 3.5m people in work who���d like more hours. This adds up to 7.4 million people, or 18.1% of the working age population.

Thirdly, we can���t blame the optimism bias. There���s massive support for a well-funded NHS, which poses the paradox that everybody seems to want insurance against physical ill-health, but not against economic ill-health.

So, why is there so little demand for full employment?

One reason is that many older workers already enjoy some job security. Two-fifths of over-35s have been with their present employer for over ten years - although among men this proportion has fallen since the early 90s.

Also, though, it���s like the old joke about the man with the leaky roof: on sunny days he doesn't need to fix it and on rainy days he can���t get on the roof to do so. The assumption that good times will last means that policies for full employment aren���t put in place then but say Wisman and Cauvel:

Government debt rises in times of crises, providing the excuse of inadequate fiscal means���.Gaining additional rights and protections is likely to seem like an implausible political goal for workers struggling to maintain what they already have.

And, they say ��� channeling Kalecki:

Guaranteed employment does not conform to the dominant ideology of capitalist societies which is generally internalized by practically everyone in the society, including workers.

This ideology, they say, manifests itself in several ways hostile to full employment policies. For example, the unemployed are blamed for their plight; governments are deemed to incompetent to implement proper macro policies or a jobs guarantee; and there���s a fear that union militancy will price workers out of jobs. In this sense, the lack of demand for full employment policies is another manifestation of the political dominance of the 1%. As Steven Lukes wrote:

Is it not the supreme and most insidious use of power to prevent people, to whatever degree, from having grievances by shaping their perceptions, cognitions and preferences in such a way that they accept their role in the existing order of things, either because they can see or imagine no alternative to it, or because they see it as natural and unchangeable? (Power: a radical view)

All this raises a thought. Could it be that the main obstacle to full employment policies is not so much one of technical economics so much as ideology and politics?

April 19, 2016

Limits of marginal productivity theory

It���s fitting that Mervyn King should have been a director at Aston Villa ��� because that job, like his previous one, has given him a close-up view of the failure of mainstream economics.

I���m referring to the idea that wages equal marginal product. Aston Villa���s wage bill this season was higher than Leicester���s. This difference is not reflected in their marginal product. In fact, Villa owner Randy Lerner is sitting on a loss of over ��200m.

This highlights an under-appreciated distinction: people are often not paid their actual marginal product, but their expected marginal product. Villa paid Joleon Lescott and a ragbag of Carlos Kickaballs ��50,000 a week because they expected them to save the club from relegation. Such expectations proved over-optimistic.

This is not an idiosyncratic example. Across whole professions, wages can be inflated because expected marginal product exceeds actual marginal product. Fund managers, for example, are paid millions for mediocre performance because gullible investors over-estimate their ability to beat the market. I suspect the same is true of corporate CEOs: managerialist ideology causes remuneration committees to over-estimate the extent to which an heroic leader can improve the company, and so pay too much. If bosses were paid their actual marginal product, Fred Goodwin and Dick Fuld would have had salaries of minus billions of pounds. They didn���t.

I���d add that there are at least three other reasons why pay can deviate from marginal product, especially at the top end.

First, value is often determined not merely by individual���s production, but by team production, which makes it difficult to identify an individual���s marginal product. As Lars Syll says (pdf):

It is impossible to separate out what is the marginal contribution of any factor of production. The hypothetical ceteris paribus addition of only one factor in a production process is often heard of in textbooks, but never seen in reality.

For example, the same manager, for example, might or might not add value depending (pdf) upon whether his skills are a good match or not with the organizations.

This can cause pay to exceed marginal product because the fundamental attribution error leads hirers to over-estimate individuals��� contributions and under-estimate organizational factors ��� as happened, for example, when ITV hired Adrian Chiles and Christine Bleakley on big money in the mistaken hope that they would attract viewers.

Secondly. wages can exceed marginal product in efficiency wage situations, where workers must be bribed not to steal the firms��� assets. This explains why bankers are paid so much. I suspect the same applies to CEOs.

Thirdly, power matters. Dani Rodrik has shown that even controlling for productivity workers are better paid in democracies (pdf) because these are associated with stronger workers��� bargaining power. In the same spirit, economists at the IMF show that CEOs pay is lower when trades unions are stronger.

All of this is to vindicate a point made by Joe Stiglitz ��� that evidence for the validity of marginal product theory, especially at the top end, ���remains thin���.

Now, you might object that some of the examples I���ve given are of disequilibrium: Fred Goodwin���s job didn���t last long, and Villa players��� prospects aren���t great. But all theories are true if you ignore the exceptions. Life is lived in disequilibrium, and a few years of egregious deviations from marginal product can generate big inequalities.

It could be that marginal product theory ��� just like simple-minded talk of incentives ��� is as much ideology as science.

April 16, 2016

Over-estimating neoliberialism

George Monbiot says that the left hasn���t come to terms with ���neoliberalism.��� His piece shows why. It might be that ���neoliberalism��� is not so much a coherent intellectual project as a series of opportunistic ad hoc uses of capitalist power.

To see this, consider two paradoxes. Paradox one is that although the left sees neoliberalism as the dominant ideology of our times, very few people actually claim to be neoliberals ��� aside, arguably, from a few Blairites and Economist writers. As an intellectual presence, neoliberalism is little more than well-connected trolling.

Paradox two is that whilst the left associates neoliberalism with free markets ��� as George says ���it maintains that ���the market��� delivers benefits that could never be achieved by planning��� ��� one feature of the neoliberal era has been the soaring wages of those claim to deny the power of markets. CEOs ��� who are in effect central planners ��� and financiers who aspire to beat the market have seen their pay increase massively since the 80s*. That���s not something that would have happened if market ideology has triumphed.

These two paradoxes have a simple solution. It lies in the fact that neoliberalism is NOT free market ideology. Here���s Ben Southwood:

Neoliberalism is comfortable with the state spending 40-50% of GDP, it is comfortable with minimum wages, redistribution, social insurance, state pensions and extensively-regulated finance.

And here ��� from a very different perspective ��� is Will Davies:

the state must be an active force, and cannot simply rely on ���market forces���. This is where the distinction from Victorian liberalism is greatest���Arguably it is the managerial freedom of corporate and quasi-corporate actors which is maximized under applied neoliberalism, and not markets as such.

Most leftists, I reckon, would describe all the following as distinctively neoliberal policies: the smashing of trades unions; privatization; state subsidies and bail-outs of banks; crony capitalism and corporate welfare (what George calls ���business takes the profits, the state keeps the risk���; the introduction of managerialism and academization into universities and schools; and the harsh policing of the unemployed.

What do they have in common? It���s certainly not free market ideology. Instead, it���s that all these policies enrich the already rich. Attacks on unions raise profit margins and bosses��� pay. Privatization expands the number of activities in which profits can be made; managerialism and academization enrich spivs and gobshites; and benefit sanctions help ensure that bosses get a steady supply of cheap labour if only by creating a culture of fear. Ben���s claim that neoliberalism is happy with a big state fits this pattern; big government spending helps to mitigate cyclical risk.

All this makes me suspect that those leftists who try to intellectualize neoliberalism and who talk of a ���neoliberal project��� are giving it too much credit - sometimes verging dangerously towards conspiracy theories. Maybe there���s less here than meets the eye. Perhaps neoliberalism is simply what we get when the boss class exercises power over the state.

* In fact, most fund managers don���t beat the market; they make their money by asset-gathering (and perhaps darker practices) rather than asset management.

April 14, 2016

Marxists & Libertarians

Here���s Robin Hanson on education:

School can have people practice habits that will be useful in jobs, such as showing up on time, doing what you are told���figuring out ambiguous instructions and accepting being frequently and publicly ranked���Schools work best when they set up [a] process wherein students practice modern workplace habits.

Bryan Caplan calls this a ���bold new theory���. Whatever its merits ��� and I think they are significant ��� it is, however, certainly not new. Here���s Louis Althusser writing in 1970:

what the bourgeoisie has installed as its number-one, i.e. as its dominant Ideological State Apparatus, is the educational apparatus���it is by an apprenticeship in a variety of know-how wrapped up in the massive inculcation of the ideology of the ruling class that the relations of production in a capitalist social formation, i.e. the relations of exploited to exploiters and exploiters to exploited, are largely reproduced. The mechanisms which produce this vital result for the capitalist regime are naturally covered up and concealed by a universally reigning ideology of the School, universally reigning because it is one of the essential forms of the ruling bourgeois ideology: an ideology which represents the School as a neutral environment purged of ideology.

And here���s Harry Braverman from 1974:

It is���not so much what the child learns that is important as what he or she becomes wise to. In school the child and adolescent practice what they will later be called upon to do as adults; the conformity to routines, the manner in which they will be expected to snatch from the fast-moving machinery their needs and wants. (Labor and Monopoly Capital, p 287)

Robin would, I guess, reach for the holy water and crucifix on learning this, but his idea is an orthodox Marxian one.

I don���t say this to embarrass him. Quite the opposite. I do so to point out that Marxists and libertarians have much in common. We both believe that freedom is a ��� the? ��� great good; Marxists, though, more than right-libertarians, are also troubled by non-state coercion. We are both sceptical about whether state power can be used benignly. And for both of us, the ideal is a withering away of the state. In these regards, Marxists probably have more in common with right-libertarians than with social democrats; Unlearning Economics has charged right libertarians with being ���lazy Marxists.���

Of course, there are obvious differences between us ��� not least about the causes of poverty and historical nature (and definition!) of capitalism. My point is simply that we have some things in common. However, whereas Marxists have engaged intelligently with right-libertarianism, the opposite has, AFAIK, not been the case ��� as Robin and Bryan���s ignorance of the intellectual history of Robin���s theory of schooling demonstrates. This is perhaps regrettable.

April 12, 2016

For an inheritance tax

The news that David Cameron got ��500,000 tax-free from his parents raises the question of how or whether inheritances should be taxed. My view is that they should be, and heavily so.

Certainly, a lot of the defences of inheritance look pathetically weak. For example:

���Because a parent���s income was taxed, taxing inheritances is a form of double taxation.���

But the same is true for most incomes. When people buy the Investors Chronicle ��� thus handing money over to me - they do so out of taxed income. Should I therefore escape income tax?

���People should be able to provide for their kids.���

Most recipients of inheritances, however, are middle-aged. And the prospect of a big inheritance can actually damage offspring, by reducing their self-reliance and incentives to work and save. As John Stuart Mill wrote:

Whatever fortune a parent may have inherited, or still more, may have acquired, I cannot admit that he owes to his children, merely because they are his children, to leave them rich, without the necessity of any exertion��� in a majority of instances the good not only of society but of the individuals would be better consulted by bequeathing to them a moderate, than a large provision���.I see nothing objectionable in fixing a limit to what any one may acquire by the mere favour of others, without any exercise of his faculties, and in requiring that if he desires any further accession of fortune, he shall work for it.

���Inheritance tax punishes aspiration.���

In most cases, though, the aspiration is an illusory one. HMRC data show that of the 279,301 estates that were left in 2012-13, a mere 6.4% attracted tax. Even if the IHT threshold were greatly reduced, only a minority would pay it.

This, though, brings me to why I favour inheritance taxes. It���s an opportunity cost argument. We should think of every penny of inheritance which is not taxed as a penny which has to be raised from income taxes. Low inheritance tax thus means high income tax.

From this perspective, those who want tax-free inheritances are exactly like benefit scroungers. They want something for nothing at the expense of hardworking tax-payers. It is, therefore, the lack of a serious inheritance tax ��� and thus the higher taxes on workers, savers and entrepreneurs ��� that is truly an attack upon aspirations.

If ��� as I find plausible ��� the prospect of getting an inheritance reduces (pdf) labour supply, then optimal taxation might require big (pdf) inheritance tax rates; these might be less distortionary than income taxes.

What���s more, low taxes for all ��� or a more equal redistribution of inheritances as the Liberal party have demanded ��� might do more to spread real freedom than a few big inheritances by the very rich.

Now, this is not to defend the existing IHT system, which has many demerits ��� not least of which is that it imposes upon people when they are disorganized and distressed. I would favour a tax on lifetime receipts of the sort suggested (pdf) by the Mirrlees commission. Surely, there is something fundamentally unjust about being able to get ��500,000 tax-free from not working, when the same sum obtained by work would be heavily taxed.

I suspect opposition to sensible inheritance taxes owes more to the rich���s colossal sense of entitlement than it does to justice or economic efficiency.

A side-point. One might argue that having talents which can earn you a good income is, morally speaking, just as arbitrary as having rich parents. This, though, is an argument for taxing inheritances and labour income the same ��� not for taxing the latter more heavily. In fact, given that making money from one���s abilities requires one to sacrifice time and freedom and enter into relations of oppression and domination, horizontal equity requires that inheritance be taxed more heavily.

April 11, 2016

Trapped by wealth

Charles Moore���s claim that one can be ���trapped by wealth��� has met with much chortling on Twitter and to calls for the world���s smallest violin. If we cut out the narcissistic moralizing that passes for leftism, however, we should see that this is in fact a very useful phrase ��� in two different senses.

First, you can be trapped onto a hedonic treadmill. There are three pathways here:

- Many men of my age are stuck in unfulfilling jobs where they have to spout the sort of guff collated by Lucy Kellaway simply because they ��� or their families ��� have acquired expensive tastes. School fees and a demanding (ex) wife make downshifting tricky. As Nicholas Taleb says, ���freedom is a very, very bad thing for you if you have a firm to run���, so you want your employees to be trapped.

- If you grow up in a rich family, you regard an expensive lifestyle as normal and so need a high income to fund it. Worse still, you might feel the need to impress a demanding father.

- Most rich folk are surrounded by other rich people, which reinforces their perception of what counts as a ���normal��� lifestyle and so creates an urge to keep up with the Joneses. One reason why Sir Malcolm Rifkind touted his services to a conman was that he thought himself hard-up relative to his peers. I suspect that Blair���s self-debasing money-grubbing has a similar motive; he���s seen how plutocrats live and wants to join them.

Secondly, wealth traps you into a distorted view of the world. Charles himself gives an example of this. A Number Ten spokie claims that ���millions of people��� engage in the sort of inheritance tax dodging that the Cameron family did. But in truth most people need no more worry about inheritance tax than about maintaining their yachts.

As I wrote recently, this isn���t the only way in which wealth warps perceptions. It causes you to under-estimate the hardship caused by what look to you like small cuts in welfare benefits. And it warps your sense of political priorities, causing you to under-rate the importance of improving the incomes of the worst off ��� even if you have benign motives. And it can breed a dangerous overconfidence.

For these reasons, Charles' phrase is correct and insightful. You can indeed be trapped by wealth. Which is one reason why inequality - and perhaps especially inherited inequality ��� is so pernicious.

April 10, 2016

Against "Resign Cameron"

Regular readers might have discerned that I am no fan of David Cameron. However, I find myself irritated by the #resigncameron protests.

The revelations about his finances tell us little. We���ve always known that he comes from a rich background; as Mark Steel says, he didn���t put himself through Eton on a paper round. And anyone who thought about it even briefly would know that such a privileged upbringing distorts one���s perceptions of the world in a politically dangerous way.

In this context, what I find surprising is how small the sums involved are. Compared to Vladimir Putin���s plundering of Russia, the ��30,000 he had invested in Blairmore is loose change ��� which makes Ken Livingstone���s call on Russia Today for him to resign quite spectacularly hypocritical. In fact, it���s not even a lot by upper-class British standards: any middle-aged man who got a degree in PPE in the mid-80s should by now have accumulated reasonable wealth had he wanted to.

Yes, Cameron does seem to have dodged inheritance tax ��� though there are more holes in that tax than in a wifebeater���s vest. And I���m assuming the information he has revealed excludes Isas ��� else hundreds of thousands in cash is a very queer asset allocation. But on current information, he has done nothing illegal or even surprising. I suspect he has behaved no worse than anybody else of similar wealth, and perhaps even better.

In this context, there are three things that trouble me about the demands that he resign.

First, there���s the hunt for the Watergate-style ���gotcha��� ��� of proof of absolute wrongdoing. This misses the point. In politics (and life) there are few undoubted heroes and villains. Instead, right and wrong are more often matters of ambiguity and dispute*. One big task of political discourse is persuade others to come round to our perception of what���s good and right. A wild goose chase for proven villains distracts us from this.

Secondly, there���s the tiresome obsession with spin. Yes, Cameron was ��� with hindsight ��� mistaken in being slow to reveal his financial affairs. But politics is, for the most part, not about how much and how quickly PMs reveal information about themselves. It���s about how they manage the machinery of government. And there���s more than enough evidence on this bigger question that Cameron's administration has failed.

But there���s something that worries me more. I fear that some of the animus against Cameron ��� not among the usual suspects who protested yesterday but among voters generally ��� is founded upon a hatred of difference. We are being invited to dislike him simply because by being rich he is not one if us ��� just as the media wanted us to hate Ed Miliband because he was a geek and to like Boris Johnson and Nigel Farage because they are ���blokes��� who like a laugh. For me, this comes nastily close to a hatred of diversity and to a narcissistic demand that politicians be like us.

There are countless reasons why I want to see the back of this stupid and brutal government. For Cameron to resign over his financial affairs would, however, be akin to Al Capone going to prison for ��� well - tax evasion.

* One thing I didn���t like about Ed Miliband was his use of the phrase ���it���s the right thing to do��� ��� as if this was anything other than egregious question-begging.

April 8, 2016

On income transparency

Should we know how much each other is paid? David Aaronovitch in the Times says yes. Andrew Lilico says no. I���m not sure about either���s argument.

David says transparency would ���help mend trust���. This is a worthwhile aim, but I���m not sure transparency would achieve it. We don���t trust banks and other multinationals not because we don���t know how much their senior employees are paid, but because there has been serial corporate wrongdoing for years.

Andrew says:

Not sharing pay details has much the same effect as school uniforms ��� it is egalitarian. If I go to play football with my friends or I go to my singing group or to church I want to interact with the people there as one of them, with a shared interest in what we are doing. I want to be judged, if judged at all, on my football skill or effort or team-play, on how well I sang in tune, and so on���I don���t want us to be judging each other on how much we earn

But we already have a vague idea of our friends��� earnings, based upon where they live, what car they drive, their occupation and even their manner and bearing. Healthy people routinely and easily put this information aside and enjoy our common activities.

Instead, I suspect there are other reasons for transparency:

One is that it might reduce the stigma attached to low wages. Just as black and gay pride were (are?) ways for marginalized groups to assert and rebuild self-esteem, so too might be the recognition of low pay.

Another is that it could shame the right people. The main opponents of pay transparency, I suspect, are those people who secretly know that they are being paid too much; a disproportionate number of these, I guess, are in London jobs. Pay transparency might put these onto the back foot: ���You���re paid how much?? For doing what??���

I confess to being unconfident about these, however. What���s at issue here is whether or how far transparency would affect culture. And cultural change is difficult to foresee.

But there���s something else. There���s some evidence that people under-estimate income inequality. Transparency would correct this. Surely, there can be nothing wrong ��� and plenty right ��� in people being better informed about social facts.

PS I earn around ��45,000 pa.

Chris Dillow's Blog

- Chris Dillow's profile

- 2 followers