Chris Dillow's Blog, page 85

March 5, 2016

On decriminalizing the sex trade

Jeremy Corbyn���s belief that the sex industry should be decriminalized should remind us of an important point ��� that genuine freedom requires equality.

Instinctively, I agree with Corbyn for the Millian reason that it���s no business of the state what consenting adults do in private, and that as little power as possible should be given to bullies and incompetents.

This, though, runs into a counter-argument ��� that, in prostitution, the parties are not consenting: Harriet Harman says prostitution is "exploitation and abuse", Julie Bindel that it is ��� one of the most exploitative industries on the planet.���

There are two parts to this claim. One is that decriminalizing (pdf) the sex trade would increase trafficking and child prostitution. However, all decent people should agree that these should have no part in the ���legitimate commerce��� of the sex industry. The solution to them is to forcefully uphold existing laws. The history of criminalizing the drink and drug trades surely shows us that you don���t clean up an industry by criminalizing it. People are sometimes trafficked to work as slaves on farms but nobody thinks the solution to this is to criminalize farm labour.

The second part of the claim is that women are compelled into prostitution by poverty or abusive partners, and that the sex trade is exploitative. As Mary Sullivan and Sheila Jeffreys write (pdf) of the legalized sex industry in Victoria, Australia:

Women are thus forced to experience exploitation on the streets, illegally, or from sex ���businessmen��� in brothels. For women in legal brothels, managers and owners demand up to 50% to 60% of takings.

Here, though, is the thing. I ��� and I, strongly suspect, Mr Corbyn too ��� favour legalization of the sex industry in the context of other policies that empower women to reject exploitation. For me, these include full employment policies to give them other career possibilities; a mass housebuilding programme to reduce rents; and ��� of course - a basic income to improve their outside options. (A basic income could be seen as part (pdf) of a feminist policy programme.) They could also include better education not just to equip women for non-sex work, but to enhance their self-esteem and confidence and hence their ability to walk away from abusive partners.

The point here broadens. There is a big difference between capitalist freedom and egalitarian freedom. The former entails the freedom to exploit, the latter gives people the real freedom to reject exploitative job offers. It���s for this reason that I have argued that genuinely free markets require Marxian policies, because a rough equality of bargaining power is necessary for legitimate commerce.

Some feminists such as Ms Bindel might reply that under such conditions, prostitution would disappear as women choose other options. Maybe, maybe not. I say: let���s find out.

Another thing: Some would object to the sex trade even under these conditions as it is, in Ms Bindel���s words, ���vile���. For me, this is no more a case for criminalizing the sex trade than the fact that some people still find homosexuality vile is a case for criminalizing gay sex. I would, however, fully endorse Ms Bindel���s freedom to remonstrate against the trade, and even to try to raise the stigma against buying sex ��� though I disagree with her.

March 3, 2016

Barriers to productivity growth

���The limits to productivity growth are set only by the limits to human inventiveness��� says John Kay. This understates the problem. There are other limits. I���d mention two which I think are under-rated.

One is competition. Of course, this tends to increase productivity in many ways. But it has a downside. The fear of competition from future new technologies can inhibit investment today: no firm will spend ��10m on robots if they fear a rival will buy better ones for ��5m soon afterwards. As someone said, it is the second mouse that gets the cheese. It might be no accident that techno-optimism exists today alongside low investment, weak stock markets and high corporate cash piles.

The second is that, as Brynjolfsson and MacAfee say, "significant organizational innovation is required to capture the full benefit of���technologies."

For example, Paul David has described (pdf) how the introduction of electricity into American factories did not immediately raise productivity much, simply because it merely replaced steam engines. It was only when bosses realized that electric motors allowed factories to be reorganized ��� dispensing with the need for machines to be close to a central power source ��� that productivity soared, as workflow improved and new cheaper buildings could be used. This took many years.

It's not just organizational change that's needed, though. So too, sometimes, is social change. For example, household appliances such as vacuum cleaners and washing machines have allowed women to join the labour market. But it is taking decades to reap this benefit, because it also requires a change in social norms to accept women as workers of equal potential.

Similarly, I suspect that if IT is to have (further?) productivity-enhancing effects, they require socio-organizational change. IT should make it easier to communicate knowledge, but this only raises productivity if it is accompanied by a breaking down of silos and methods to facilitate co-operation and the exchnage of ideas within companies. It also should facilitate working from home, which could increase aggregate productivity by reducing house prices thus shifting spending away from a sclerotic sector of the economy towards more dynamic ones.

Without these changes, the internet might be like Hero of Alexandria���s aeolipile ��� an impressive device of little macroeconomic consequence.

However, there are always obstacles to the social and organizational change necessary for technical change to lead to productivity gains. These might be cognitive ��� such as the Frankenstein syndrome or ���not invented here��� mentality. Or they can be material. Socio-technical change is a process of creative destruction, the losers from which kick up a stink; think of taxi-drivers protesting against Uber.

Worse still, these losers aren���t always politically weak Ludditites. They can be well-connected bosses of incumbent firms, or managers seeking to maintain their power base.

So great are these obstacles that Joel Mokyr has coined the phrase Cardwell���s law:

Every society, when left on its own, will be technologically creative for only short periods. Sooner or later the forces of conservatism, the "if-it-ain't-broke-don't-fix-it," the "if-God-had-wanted-us-to-fly-he-would-have-given-us-wings," and the "not-invented-here-so-it-can't-possibly-work" people take over and manage through a variety of legal and institutional channels to slow down and if possible stop technological creativity altogether.

He���ll not thank me for saying so, but this echoes Marx:

At a certain stage of development, the material productive forces of society come into conflict with the existing relations of production or ��� this merely expresses the same thing in legal terms ��� with the property relations within the framework of which they have operated hitherto. From forms of development of the productive forces these relations turn into their fetters.

The big question facing us is, therefore: do we have the right set of institutions to foster the socio-organizational change that beget productivity growth? These require a mix of healthy markets, to maximize ecological diversity; a financial system which backs risky new-comers; property rights which incentivise innovation; and state intervention that facilitates all these whilst not being captured by Luddites. If our politics weren���t so imbecilic, this question would be getting a lot more attention than it is.

March 2, 2016

Not seeing trade-offs

There���s one view on the Brexit row that seems to me to be under-heard. It���s that whilst Brexit might be (slightly) economically damaging, this is a price worth paying for increased national sovereignty and a closing of the democratic deficit**. Such a view is of course questionable, but it seems to me at least tenable - certainly more so than some of the rubbish that's being spouted.

But we���re not hearing it. Instead, outers seem to think that Brexit would both make us better off and increase national self-determination. The converse is true for most of the inners: they too seem to feel no conflict between the various values involved.

This failure to acknowledge conflicts between values is, of course, not confined to the Brexit debate. Very few of those who support immigration controls do so because they believe social cohesion is worth having at the expense of some liberty and prosperity ��� or at least they don���t feel those costs as a deprivation. Similarly, right libertarians deny that equality is a value, rather than believe it is a value worth sacrificing for liberty and prosperity. And leftists don���t see that a living wage or higher corporate taxes might cost jobs.

What we see in all these cases is a denial of Isaiah Berlin���s claim (pdf) that values conflict:

The notion of the perfect whole, the ultimate solution, in which all good things coexist, seems to me to be not merely unattainable ��� that is a truism ��� but conceptually incoherent; I do not know what is meant by a harmony of this kind. Some among the Great Goods cannot live together. That is a conceptual truth. We are doomed to choose, and every choice may entail an irreparable loss.

This poses the question: why is there such widespread failure to see Berlin���s point?

A large part of the answer, I fear, is that partisans tend to be fanatics who overstate their case; not many of the protagonists in the Brexit debate take the ��� to me reasonable ��� view that the stakes are low.

You might think that in saying this I���ve fallen for a selection effect. We hear disproportionately from dogmatists and fanatics simply because TV and radio producers are more likely to invite them onto their shows than people with nuanced views who are troubled by trade-offs*.

But maybe something else is at work. It���s that once you���ve persuaded yourself of the merits of an argument, three cognitive biases kick in to play down trade-offs:

- Asymmetric Bayesianism. We tend to be more sceptical about arguments from the opposing side than from our own, with the result that a balanced presentation of the evidence increases our dogmatism.

- Wishful thinking. For example, those who value national self-determination want to believe that Brexit will also make us better off ��� and wishes often beget beliefs.

- The halo effect. We tend to believe that good things go together, even though they needn't. For example, attractive defendants are more likely to be acquitted than ugly ones. David Leiser and Ronen Aroch have shown (pdf) that this characterizes lay people���s thinking about economics. They show that non-economists apply a ���good begets good heuristic���: they tend to believe that good things lead to other good things.

Berlin went on to write that those who deny trade-offs rest on ���comfortable beds of dogma���. He should have added that such beds are easy to make.

* I���d like to hear interviewers ask: ���what is the strongest argument your opponents are making?���

** Update. John Springford at the CER points out this trade-off - but his sort of voice isn't hard much in the date.

March 1, 2016

Private school distortions

Owen Jones claims that the disproportionate number of privately-educated people in politics and the media ���damages us all���. I agree. As Owen says:

We all look at the world through a prism shaped by our experiences: of our parents, our schools, our friends, and our colleagues and associates.

The problem is that the dominance of the privately-educated leads to one prism dominating political discourse, leading to a damaging lack of cognitive diversity. I mean this in several ways:

- If you come from a rich background, you don���t properly understand poverty*. I suspect that one reason why Tories support the bedroom tax isn���t so much that they hate the poor as that they just don���t realize that a few pounds matter so very much to the worst off.

- If you���re wealthy, you are higher up Maslow���s hierarchy of needs. This can lead to a shift in one���s ideas about what matters. Abstract issues such as sovereignty or ���Britain���s standing in the world��� become more important, whilst bread-and-butter issues become less so. "The deficit��� is regarded as important even though it is far from obvious how this makes anyone materially worse off, whilst the causes of long-term stagnation in real wages ��� such as low productivity growth or job polarization ��� are downplayed. I suspect that one reason why the recent recession left virtually no cultural imprint ��� in contrast to the 80s giving us Boys from the Blackstuff and two-tone ��� is that the arts are now dominated by the privately educated.

- Your environment determines who you regard as ���us��� and who as ���them���. This too can colour one���s priorities. If you come from a well-off background, you���ll come to regard poor people as ���them���, to be controlled by criminal justice policy or nudges. But because the rich are more familiar to you, you���ll see them as less of a threat. The question of how to restrain the rapacity or incompetence of bosses will therefore be less important to you. I suspect this process also helps explain the (to me otherwise inexplicable) acclaim given to Boris Johnson. If a politician from a working class background has been sacked twice for dishonesty and had associated with violent criminals, would he be seriously talked about as a future Prime Minister?

- The privately educated tend to be self-confident. This can generate over-confidence in one���s own policies and over-confidence about the potential for top-down management.

Now, I���m not making a party-specific point here. I have Tony Blair in mind as much as Cameron. And Clement Attlee���s government contained more old Etonians than David Cameron���s: it might be no accident that a member of that government, the Wykehamist Douglas Jay, gave us the phrase, ���the man in Whitehall knows best���.

The BBC is complicit in this: its three most senior political reporters ��� Kuenssberg, Landale and Smith ��� were all privately educated.

I also appreciate that I���m vulnerable to a ���tu quoque��� objection: I too have only a partial perspective, shaped by my background. However, a Marxist from a single-parent family in an inner City who went into Oxford and banking is at least vaguely aware of the partiality of his perspective. Those from rich backgrounds who surround themselves with like-minded people might lack this (dis)advantage. Fish never know they are wet.

* Hume���s distinction between ideas and impressions matters here. If you���ve had to hide from the rent-man (one of my few childhood memories), you have an impression of poverty. If you���ve only heard and read about poverty, you have only weaker impressions.

February 28, 2016

(Mildly) against Brexit

Like most economists, I���m minded to oppose Brexit. This isn���t because I���m an admirer of the EU: it is an unlovely institution. I���m as unmoved by appeals to European ideals as I am by talk of sovereignty or British national identity. Instead, for me, this is merely a pocket-book issue ��� are we better off in or out? ��� and I���m unconvinced by the outers��� case.

If it could be shown convincingly that leaving the EU would lead to us being an open, free-trading country I���d be tempted. But I doubt this is the case. I doubt we���d get good free trade treaties, especially as these will be negotiated by men lacking competence or goodwill. More likely, as Paul says, such treaties will be distorted by lobbyists and special interests, so we���d end up with something worse than TTIP. Granted, free trade with the EU would be in everyone���s interests: but a glance at the euro zone���s macroeconomic policy suffices to show that the EU cannot be relied upon to act in its citizens��� interests.

But even if I���m wrong, the journey to being a liberal free-trading nation will be a choppy one. As Michael Emerson says, Brexit is ���a very messy prospect, with years and years of negotiation lying ahead in a climate of uncertainty over the outcome���. Such uncertainty could dampen capital spending and investment in exporting activity sufficiently to offset for a very long time the benefits of freer trade ��� especially as those benefits will themselves take years to be reaped.

I agree with the outers that being in the EU ties us to a sclerotic and dysfunctional economy. Carl is right to deplore the EU���s fetish with austerity, and Andrew is right to say that there are risks to staying in. But I interpret these arguments differently. We are tied to the European economy not by mutable political agreements but by brute geography; all countries trade a lot with their near-neighbours. Even outside the EU, we would be vulnerable to its economic mismanagement. (I���m tempted to add that, in the EU, we have a chance of mitigating that mismanagement, but I fear this would be too optimistic.)

So far, I���ve assumed that the case for leaving is that it would be a step towards an open forward-looking economy. But I fear that this is not what many outers want. Let���s face it: at least some of them are reactionary bigots who see withdrawal from the EU as a means of imposing tougher immigration controls. Even leaving aside their illiberalism, these would probably be bad for the economy.

Similarly, Michael Gove���s hope that any government money saved by Brexit could be invested in science and technology seems to me na��ve. For one thing, insofar as Brexit depresses GDP it would reduce tax revenue, which folk like him would regard as a reason to cut spending. And for another, I fear it���s more likely that, if there is a windfall, it would be used for tax cuts for the better off. Net, science funding might be jeopardized by Brexit.

I know I should dissociate the case for Brexit from some of the deeply unattractive personalities who support it ��� but I���m struggling to do so.

In saying this, I don���t mean to say that Brexit would be disastrous. It wouldn���t be. Even on the harshest calculations, it would probably cost less than austerity has cost us, and the immediate costs of heightened uncertainty could be offset by looser fiscal policy. On the spectrum from Neil Woodford���s view that the economic argument about Brexit is ���completely bogus��� to Cameron���s claim that Brexit would be the ���gamble of the century���, I���m closer to Woodford. Our relationship with the EU is a big issue in the media because of the psychiatry of the Tory party, not because the economic stakes are large.

This raises the question: what might change my mind?

If it could be shown that EU membership were a binding constraint against liberal socialistic wealth-enhancing policies such as a citizens income, worker democracy or non-cretinous macroeconomic policy, I���d favour Brexit. For now, however, the obstacles to these policies are to be found nearer home.

February 25, 2016

The living wage & productivity

Nida Broughton at the SMF says:

If businesses can increase productivity there is less likely to be a risk of higher unemployment as a result of the introduction of the National Living Wage.

This is true only in a very particular sense. In other senses, increasing productivity means raising unemployment.

Let���s start with the definition of productivity. It is value-added (GDP) per hour worked. This definition tells us that there can only be four ways in which productivity can rise. To see them, take the case of the Rovers Return*.

One way in which it could raise productivity would be simply for Michelle to cut their hours and expect Sean, Eva and Sarah to spend less time lounging around and more time serving customers.

In this sense, the claim that the NLW will raise productivity is the same as the claim that it will reduce employment.

So, how can Ms Broughton possibly be right?

It���s because there���s a second possible way in which productivity can rise. Workers could produce more value-added. For example, Sean, Sarah and Eva could mix fancy cocktails instead of pouring pints. If so, the Rovers customers would pay more for the better service, thus covering the higher wage costs.

Personally, I find this improbable. Norris Cole and Tim Metcalfe aren���t going to start drinking strawberry daiquiris.

A third possibility is that the Rovers could get more customers, so the same number bar staff will produce more value-added.

This will not happen because the NLW shifts income from employers to workers, thus redistributing income from people who have a low propensity to spend to those who have a higher one. For one thing, Corrie���s employers, such as Michelle and Carla (aka the future Mrs Dillow), in fact spend a lot. And for another, workers at Underworld will see their higher wages partly offset by lower tax credits. The upshot will be a cut in aggregate demand.

How, then, might Michelle attract more customers? She could promote the pub better, for example by having karaoke or singles nights. But these have already been tried, with mixed results. If there were obvious ways for the Rovers to get more punters, they would have been tried by now.

This leaves only one last possibility: Michelle could try to raise prices. She could get away with this, because demand is relatively price-inelastic; the Flying Horse will probably raise prices too. Value-added per worker would thus rise because customers are paying more for their beer. However, this would leave the Rovers��� customers with less to spend elsewhere. Roy and Dev might therefore suffer a loss of demand ��� although it���s unlikely Dev will sack Erica as a result.

Overall, then, I fear that if the Rovers is to increase productivity, it will happen by cutting hours. This is just what the OBR expects. It expects total working hours to fall by four million by 2020 as a result of the NLW (p204 of this pdf.)

Productivity, though, is not the only margin of adjustment. Michelle might simply accept the higher wage costs and the lower profits they imply. Or she might try to employ younger bar staff: the NLW only applies to over-25s.

Whichever it is, the NLW will impose costs upon someone. It is not a magic money tree.

* Almost all issues in economics can be understood through football or Corrie.

February 23, 2016

Inequality against freedom

In making a libertarian case for Bernie Sanders, Will Wilkinson draws attention to an awkward point for right-libertarians ��� that inequality is the enemy of freedom.

He points out that Denmark ���the sort of country Sanders wants the US to be more like ��� has greater economic freedom than the US. This, he says, ���illustrates just how unworried libertarians ought to be about the possibility of a Denmark-admiring, single-payer-wanting, democratic socialist president.���

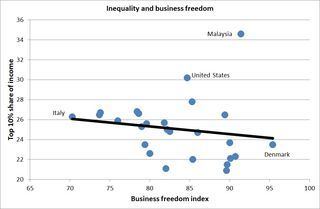

Will is not taking freak cases here. My chart plots a measure of income inequality (taken from the World Bank) against the Heritage Foundation���s index of business freedom ��� their measure of how government regulates firms ��� for 26 developedish nations. There is a slight negative correlation between them, of 0.16. If anything, I���m biasing the chart against the point I want to make: if I were to exclude Malaysia, which is free and unequal, or include Chile (which is unfree and unequal) the negative correlation would be much greater.

Inequality doesn���t just reduce freedom for workers. It reduces freedom for business owners too.

Will says this is because countries that want to tax and redistribute must have a healthy economy, which requires business freedom. I suspect that there are two other mechanisms at work.

One is that many of the rich have no interest in economic freedom. They want to protect extractive institutions and the monopoly power of incumbents from competition. They thus favour red tape, which tends to bear heavier upon small firms than big ones. This, I suspect, explains why inequality and unfreedom go together in Latin America, for example.

Secondly, people have a strong urge for fairness. If they cannot achieve this through market forces, they���ll demand it via the ballot box in the form of state regulation. As Philippe Aghion and colleagues point out, there is a negative correlation between union density and minimum wages: minimum wage laws are more likely to be found where unions are weak. Regulations, in this sense, are a substitute for strong unions ��� and, I suspect, a bad substitute because they are more inflexible.

Through these mechanisms, inequality is the enemy of freedom even in the narrowest right-libertarian sense of the word.

That said, it doesn���t follow that people who want greater income equality will necessarily promote economic freedom: Megan McArdle might be right to say that Sanders can���t or won���t much enhance it. We should, though, ask: what sort of egalitarian institutions and policies might increase freedom?

For me, the answer is clear: those which increase workers��� bargaining power. This means fuller employment and a jobs guarantee; stronger trades unions; and a citizens��� basic income. The point here is that if workers have the power to bargain for better wages and conditions, and the real freedom to reject exploitative demands from bosses, then we���ll not need so much business regulation. In this sense, greater equality and cutting red tape go together.

What don���t go together ��� in the real world ��� are inequality and freedom. So-called right-libertarians therefore have a choice: you can be shills for the rich, or genuine supporters of freedom ��� but you can���t be both.

February 22, 2016

Brexit: how big an issue?

Just how big an issue is Brexit? Cameron says it is ���one of the biggest decisions this country will face���. Gove says it���s ���the most difficult decision of my political life.��� But is it?

The best economic case for exit I���ve seen comes from Patrick Minford, who estimates the gains to leaving at around 10 per cent of GDP: these come from less regulation and freer trade with non-EU countries. On the other hand, John Van Reenen and colleagues think Brexit might cost us up to 10 per cent of GDP, as we face trade barriers with the EU.

There are big uncertainties here, such as what sort of trading regimes we���d face outside the EU, and how big are trade multipliers: to what extent does trade (pdf) encourage innovation?

Two things make me sceptical about big estimates, however. One is a paper by John Landon-Lane and Peter Robertson. They point out that, give or take a standard error, rich national economies grow at pretty similar rates over the long-run. This, they say, implies that ���there are few, if any, feasible policies available that have a significant effect on long run growth rates.���

The second concerns the maths of economic growth, described by Dietrich Vollrath. Even if Brexit does raise our potential growth rate, it would take many years for the economy to reap those gains. He says:

Even if [insert policy here] opens up a big gap between potential and actual GDP, this doesn���t translate into much extra growth. In fact, the effects are likely so small that they would be unnoticeable against the general noise in growth rates year by year���Massive structural reforms are not capable of generating immediate short-run jumps in growth rates.

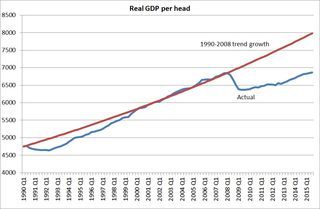

Let���s, though, put my scepticism aside and put those 10 per cent-ish numbers into context. Even 10 per cent might well be less than the cost of the financial crisis and subsequent bad economic policy: if GDP per head had grown at its 1990-2008 rate since 2008, it would now be 14 per cent higher than it actually is.

In macroeconomic terms, therefore, the Brexit debate is less important than the question of how to close the GDP gap that���s opened up since 2008.

Which poses the question: why is the Tory party fixated on the former whilst paying so little attention to the latter? The most respectable reason is that Brexit isn���t just an economic issue at all, but is instead about sovereignty and national identity. A less respectable one is that it is about tribal fissures within the Tory party, and careerist manoeuvring to exploit those divisions.

This is one reason why, if we must have a referendum on this matter, I would rather it were a demand-revealing referendum in which people vote not simply ���leave��� or ���remain��� but rather a sum of money to express their estimate of the cost of them of leaving or staying.

One great virtue of such a scheme is that it forces the protagonists to maintain a sense of proportion. Picture the scene. Someone on the Today programme is putting the case for leaving. John Humphrys then asks: ���OK Mr Gove/Farage/whoever. How much will you pay to leave?��� The nature of the debate is thus transformed, from high-blown hyperbole to a sober assessment of the costs and benefits.

As it is, I fear we���ll be hearing too much hyperbole and misplaced certainty and not enough perspective and doubt. Worse still, I suspect that the media ��� including much of the BBC ��� will be complicit in this distortion of the debate.

February 21, 2016

On generational differences

One of my first reactions to the row about anti-semitism at Oxford University Labour Club was: why are the silly sods paying so much attention to Israel-Palestine given that the issue seems to drive so many people insane? In my time, it was apartheid that bothered us, not Israel.

But then it struck me: to today���s students, apartheid is distant history. Nelson Mandela was freed in 1990, seven or eight years before today���s first-year undergraduates were born. To today���s students, anti-apartheid protests are as far away as the Aldermaston marches or Suez crisis were to my generation.

This is only one way in which there���s a generational gulf between today���s students and my generation. Douglas Adams proposed the following rules about attitudes to technology:

1.Anything that is in the world when you���re born is normal and ordinary and is just a natural part of the way the world works.

2. Anything that's invented between when you���re fifteen and thirty-five is new and exciting and revolutionary and you can probably get a career in it.

3. Anything invented after you're thirty-five is against the natural order of things.

These surely apply. I suspect my generation���s default setting is to think of books rather than the internet as the repository of research, and to regard Spotify and Tinder as novelties.

Or take attitudes to football. My generation was brought up to think of Liverpool as the dominant team in England. But they���ve not won the league since 1990. To today���s students, Rush and Dalglish are as temporally distant as Stan Cullis was to us.

Or music. The Spice Girls are as temporally distant to today���s students as the Beatles were to us. And ���old skool��� dance music ��� the music of the early 90s ��� is as distant as 1950s rock n roll was to us.

I suspect this is true of political attitudes too. Take four examples:

- My formative years were shaped by overt class struggle: the strikes of the 70s and 80s and Thatcher���s attacks on unions. To today���s young people, class is less salient ��� which is, of course, not to say that it���s less important.

- In my day, there were fewer graduates and hence less competition for good jobs. Today���s students face more of a buyers��� market, and so must be more career-oriented whist at university.

- 50- and 60-somethings grew up under the threat (which might have been exaggerated) of the Soviet Union. We had therefore a large and obvious example of the dangers and costs of a lack of political freedom. Today���s young people don���t have so salient an example, and so might be less aware of the value of free speech and discussion.

- My generation grew up in violent times: today���s youngsters didn���t so much*. I suspect this might shape attitudes in all sorts of ways, because we are less likely to regard others as threats. But it might help explain campus politics: students worry about ���microaggressions��� because they don���t have bigger aggressions to fret about.

In saying all this, I���m taking a Humean position. There is a big difference between impressions and ideas. Our direct experiences, reports by our friends and TV news stories have a more forceful effect upon our minds than what we read about in books. My knowledge of WWII is of a very different kind to that of my grandparents.

This, I think, is also the presumption of a lot of identity politics: growing up as, say, black or gay or a woman gives us different presumptions and instincts than we���d have if we grew up white, straight or male. But the same, surely, is true for cohorts; growing up in the 1970s gives you different presumptions than growing up in the 00s.

This is not to say that generational cleavages must be massive and confrontational, any more than other identity-based ones must be. Instead, my point is simply that we must be aware of these differences ��� and we never will be if we don���t try.

* Is sexual violence and exception to this?

February 19, 2016

Built by history

It���s appropriate that Martin Wolf���s criticism of proposals to introduce more market forces into higher education should appear the day after Man Utd���s abject defeat to Midtjylland. This is because football clubs and universities ��� and in fact big businesses ��� have something in common.

That something is the power of history. As Martin says, universities rely upon reputation, and reputation is built over time. Oxford is one of the world���s best universities not because it is remarkably well-managed, but because of its history.

Exactly the same is true for football clubs. Man Utd still get capacity crowds not because they are playing brilliant football ��� as their fans noted last night, they are not ��� but because they benefit from a loyalty built up over decades. People watch Man Utd not to savour the sublime talent of Marouane Fellaini or workrate of Memphis Depay but because they got hooked on Best-Law-Charlton-Scholes. Similarly, Oxford���s reputation owes far more to Evelyn Waugh than it does to its here today-gone tomorrow-forgotten the day after Vice Chancellor*.

What���s true of football clubs and universities is also true for big companies. If I ask you to picture, say, Ford or Coca-Cola, the image that comes to mind might well be one from decades ago.

What Edmund Burke said of society applies to organizations ��� at least those with big brands. They are ���partnerships . . . not only between those who are living, but between those who are living, those who are dead, and those who are to be born.���

And brands generate rents: if you spend ��30,000 on a BMW you���re buying ��20,000 worth of car and ��10,000 worth of badge. I get paid for working at the IC but not for blogging because the IC has, over the years, built a monetizable brand. The Glasers take cash out of Man Utd thanks to a brand built by past players and managers. One of the strongest facts about CEO pay is that it is correlated with firm size (pdf), but that size is often a product not of the CEO���s own efforts but of historic growth. As Barack Obama said (in a different but applicable sense), ���you didn���t build that.���

In all these cases, what���s going on is a form of exploitation. Bosses and workers today are making money not (just) from their own efforts, but from the work of their predecessors. They are not (just) value-adders but value-estractors.

Of course, this point generalizes. I owe my income not just to the IC���s history but to British history generally. I���m rich not because of my talents but because as Gary Lineker says I was fortunate enough to be born in this country rather than in one that hasn���t enjoyed three centuries of economic growth.

All this provides a justification for (globally) redistributive income taxes. But perhaps it justifies more than that. Seen from this Burkean perspective, bosses of great organizations ��� universities, businesses, whatever - are merely custodians of them. This makes it all the more necessary to restrain their power by more collective forms of leadership ��� a point which is all the more true because there are also other cases for restricting bosses��� control and empowering workers.

* I was going to say that its reputation is founded upon the calibre of its graduates, such as um, err -wait they���ll come to me.

Chris Dillow's Blog

- Chris Dillow's profile

- 2 followers