Chris Dillow's Blog, page 84

March 21, 2016

Salience, & obliquity

Is Jeremy Corbyn leader of the Labour party for the same reason that DFS is always having sales?

I ask because of a new paper by Markus Dertwinkel-Kalt of the University of Cologne and Gerhard Riener of Mannheim University. They show that, when faced with a choice between products with different types of rewards, consumers often focus (pdf) upon one eye-grabbing feature and underweight others ��� a decision which isn���t always rational. This is closely related to the theory (pdf) that ���consumers attach disproportionately high weight to salient attributes.��� And it���s consistent with Michael Porter���s advice that companies should offer customers either low prices or high quality but not be stuck in the middle.

This explains a lot of behaviour:

- DFS always has a sale because ���50% off��� is a more salient offer to customers than a reasonable settee at a fair price.

- The clich�� for years has been that mid-market supermarkets such as Sainsbury and Tesco have lost out to those offering more salience ��� either Lidl���s low prices or Waitrose���s quality.

- Easyjet offer low air fares and then sting travellers for everything because low headline ticket prices are eye-grabbing.

Corbyn���s popularity with Labour members fits this pattern. When faced with two or three candidates who were much of a mushy muchness, they plumped for the more salient option.

I suspect a similar thing might be true for the Brexit referendum. Voters��� decisions will be swayed by them attaching lots of weight to a particular outstanding feature: for me, this is the short-term uncertainty that Brexit would cause.

You might wonder how all this can be consistent with the compromise effect ��� our tendency to choose mid-ranged options, such as middlingly-priced items on a restaurant menu.

Simple. The compromise effect works by exploiting the contrast effect, thus making the offered product more salient. The average-priced dish looks good value when contrasted to the expensive one: the modest home looks nice contrasted to the hovel. In this sense, the compromise effect and the focusing effect are compatible: both say that we choose the salient option.

This is true in politics too. An appeal to the ���centre ground��� succeeds if a party can credibly say: ���they are extremists; we are moderates.��� But the claim ���we are more moderate than them��� often fails ��� as many unemployed Lib Dem ex-MPs would testify.

Herein lies a nice paradox. Corbyn, more than most politicians, is innocent of marketing tricks, behavioural economics and the darker arts of persuasion. And yet he benefited from the focusing and salience effects whilst his supposedly more PR-savvy rivals failed. Perhaps this is one more data-point in favour of John Kay���s theory of obliquity - that our goals are often best achieved when pursued indirectly.

March 17, 2016

The incumbency advantage

Imagine if, last week, someone had proposed a small short-term fiscal easing followed by a ��13.9bn tightening in 2019-20*. Pretty much everyone would have scorned such an idea. Political journalists would point out that unspecified spending cuts at the end of the parliament lack credibility. And economists would say that the threat of higher corporate taxes then would dampen capital spending now ��� and, they���d add, there���s no point tightening so much merely to achieve a budget surplus that���s pointless anyway.

Nobody for one moment would think this remotely sensible, and nobody would want to entrust its proposer with high office.

However, although Osborne has attracted criticism from sensible (pdf) people across the political spectrum, and ��� in fairness ��� lacklustre press coverage, the mainstream does not seem to be giving him the scorn and derision that his buffoonery deserves. I reckon there are at least five reasons for this.

One is deference. People respect power and overconfidence ��� even if unmerited ��� more than they should.

Another obvious one is plain vested interests. There���s a noisy client group that benefits from cuts to capital gains tax, the raising of the higher rate threshold and a ��1000 a year handout ��� which is what the Lifetime Isa is. Nobody complains about being given free money.

Thirdly, Budgets are what Rodney Barker calls rituals of self-legitimation. They come surrounded with their own rhetoric of ���judgment���,���prudence��� and ���long-term���. People infer that a 150-page report must be sensible, even if much of it is drivel. And there���s a tendency for folk to assume that if a man is wearing a suit and talking about money, he must be serious and trustworthy ��� a habit which financial advisers have exploited royally for years.

Fourthly, the ���gimmicks��� of which Martin Wolf complains serve a purpose ��� they throw up smoke. The tax on sugary drinks might be silly, but it distracts from the Lifetime Isa, which in turn distracts us from the dubious claims to be closing tax loopholes, which distract us from the macroeconomic judgement, and so on.

Finally, there���s a form of the status quo bias; existing policies are more tolerable than proposed ones. As the old saying goes, it is easier to ask forgiveness than permission. Some neat research by Christoph Merkle has established this. He shows that, after losing money, investors are less unhappy than they thought they would be: the fear of a loss is worse than the reality. I suspect that this translates into politics: policies that seem unconscionable when they are proposed become bearable after they have been enacted.

My point here is a simple and depressing one. It���s that, as I���ve said, Osborne has huge advantages over the Labour party, regardless of the merits of their arguments.

* Table 2.1 here is the Budget: the speech was a different thing.

March 15, 2016

How to write a Budget

When he takes office, every Chancellor is given a letter from a colleague of Screwtape which tells him how to write Budgets. I���ve got a copy of this, which I reproduce below.

Dear Chancellor.

Some new Chancellors believe that Budgets are a chance from them to earn a reputation as the man who transforms the economy. Cleanse yourself of such childish nonsense. A sensible tax system, along the lines suggested by the Mirrlees review, would not need to be tinkered with every few months; taxes should be predictable. The Budget is not about the economy. It���s about something much more important than that. It���s about YOU.

A Budget is a pantomime in which you are the star. Like all pantomimes, it must follow a rigid structure.

Your preamble will discuss the general economic background. If you���ve taken over from the opposing party, you say what a mess they���ve left. If you���ve been in the job a few years, cherry-pick a few facts to make it look as if you���ve been a success. If the economy���s weak, for example, celebrate low inflation and low mortgage rates. If it���s strong, talk about jobs.

Waffle about prudence, stability and tough choices is always advised here. Make your job seem more difficult than it is.

You then discuss economic forecasts. Under no circumstances must you say that these are usually wrong. Nor must you discuss margins of error. A Budget is no place for serious economics. Instead, the forecasts allow you to talk about the global economy. This gives you gravitas. If the outlook is good, you can claim credit for your past policies. If the outlook is bad, blame your predecessor or the challenging world environment and say you must make tough choices: it���s much better to look tough than mean.

You then announce a long list of measures intended to help charities, small businesses, science and new industries. These measures shouldn���t involve more than a few million and won���t make a lick of difference. But associating yourself with science and good causes whilst appearing generous will make you look good.

Also, announce a few infrastructure projects. Journalists are wise now to the Yes Minister theory of infrastructure spending, so you can���t do anything about the A34/M40 junction. Broadband and something called ���the North��� are popular, however.

Oh, and don���t forget to bugger about with North Sea oil taxation. It���s an annual tradition.

Promise to raise a few billions by making efficiency savings and by clamping down on tax avoidance and loopholes. Skimp on the details, though. And if you���ve been in office a few years, never explain why you didn���t make these ���savings��� earlier. You can probably also get away with raising money by taxing banks or utilities. Nobody likes them.

You might also want to raise money in other ways, such as by welfare cuts. Ensure that you do so in the most complicated way you can. And never mention the sums involved. The great thing about a Budget is that you can get away with a complete lack of proportion. If you announce a litany of tiny giveaways followed by a complicated change to tax credits or welfare benefits you can appear generous even if you���re not.

Of course, policy wonks will spot this. But by the time they do so, the public will have gotten tired of Budget coverage so they won���t care. It���s the initial headlines that matter, and these are provided by gullible political journalists who only hear the speech and don���t understand numbers.

Next, take a penny off a pint. It makes Radio 5 Live listeners happy.

Then it���s time for personal taxes. Raise the personal allowance. This allows you to boast of taking low-paid people out of tax. The main beneficiaries will of course be higher earners. So you can look as if you���re helping the worst off whilst in fact benefiting the median voter. It���s a double win.

Then move onto savings. You want to ���encourage savings���, so cut taxes on these: your civil servants might have spoken about income and substitution effects, but if you���re wise you���ll have ignored them.

Finally, there���s the rabbit from the hat. Always end your speech with a surprise giveaway.

Above all, remember what the Budget is all about. It���s about how you appear in newspaper headlines the following day. Nothing else matters.

March 12, 2016

Labour's credibility problem

Simon points out that John McDonnell���s proposed fiscal rule is much better than Osborne���s. This poses the question: why, then, should Labour be struggling so hard to establish ���credibility��� with the electorate about its approach to the public finances?

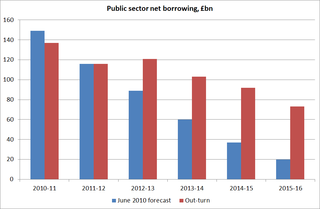

It���s certainly not because Osborne���s policy has been a success. OBR data show that, in the last five years, the government has borrowed ��183bn more than the OBR expected (pdf) in 2010. This is strong evidence that austerity has been counter-productive, as any schoolboy Keynesian would have predicted.

Instead, I fear that there are less good reasons why Labour is struggling. One reason is that voters have bought the story that Labour ���over-borrowed��� in the 00s. I���ve argued that this story is false - its borrowing was a reasonable reaction to the savings glut and investment dearth ��� but its plausibility has been enhanced by some Labour figures��� self-abasing desire to apologize anyway.

There is, though, something else. The fact that Osborne is wrong is, paradoxically, an advantage for him. The reason for this has been pointed out in a new paper by Peter Schwardmann and Joel van der Weele. They show that people who deceive themselves are better able to deceive others. This corroborates research by Cameron Anderson and Sebastien Brion, which has found that the over-confident are more likely to be hired than more rational candidates, because they send out more ���competence cues���, and so their irrational overconfidence is mistaken for actual competence. As Matthew Hutson says, ���to be a good salesman, you have to buy your own pitch.���

Osborne���s talk about cutting borrowing fits this pattern: his overconfidence that he can cut borrowing has been mistaken by voters for an ability to actually cut borrowing ��� an ability he has not, thus far, possessed to the extent that he claimed.

In this, he has been helped by other factors. One, of course, is media bias. As Simon says, fiscal policy is reported not so much by economists ��� most of whom are opposed to Osborne���s policy ��� but by political reporters.

This matters in two ways, even leaving aside partisan bias. One, as David Leiser and Ronen Aroch have argued (pdf), is that laypeople���s thinking about economics relies upon a ���good begets good��� heuristic. They believe that good things have good effects. The desire to cut government borrowing is seen as ���good���, so people think it must have good effects ��� thus ignoring the paradox of thrift.

The other is plain deference. As Adam Smith wrote:

We frequently see the respectful attentions of the world more strongly directed towards the rich and the great, than towards the wise and the virtuous. We see frequently the vices and follies of the powerful much less despised than the poverty and weakness of the innocent���The great mob of mankind are the admirers and worshippers, and, what may seem more extraordinary, most frequently the disinterested admirers and worshippers, of wealth and greatness. (Theory of Moral Sentiments, I.III.29)

Whatever John McDonnell does, therefore, he will struggle to achieve ���credibility���. As a wise man asked, ���what chance have you got against a tie and a crest?���

March 11, 2016

Skill vs morality

There���s a trade-off between skill and moral behaviour, according to new research.

Armin Falk and colleagues got people to sit a form of IQ test, except that some subjects were explicitly told it was an IQ test whereas others were told it was just a questionnaire. Some were then told that for each question they got right, the probability would increase of a mouse being gassed to death. They found that the subjects sitting the IQ test were more likely to answer questions correctly ��� at the possible expense of the mouse���s life ��� than those only filling in the questionnaire. They conclude:

Striving for pleasures of skill can have negative moral consequences and causally reduce moral values.

This is not the only paper to establish a link between technical skills and bad behaviour. Francesca Gino and Dan Ariely have found that creative people tend to be more (pdf) dishonest than others.

There is, I fear, no lack of external validity here. To take a few diverse examples:

- Scientists sometimes work on projects with potentially dangerous effects, such as enhancing viruses. Falk quotes Sir Mark Oliphant, a member of the Manhattan Project: ���if the work���s exciting, they���ll work on anything.���

- Soldiers can fight well even if a war is unjust.

- Civil servants can work diligently to implement policies we might find repellent (though it���s questionable how often this is happening at the DWP).

- Bank traders rarely worry that their work might be socially useless.

- Accountants and lawyers can be untroubled by ��� or even take pleasure in ��� devising tax-dodging wheezes.

- Even the best footballers, as well as Diego Costa, sometimes dive.

Readers might object that I fall into this category. If I do well in my day job ��� a matter which I leave others to judge ��� the best that happens is that already-wealthy people get even richer. I honestly confess to being untroubled by this.

Herein, though, lies a paradox. All this seems to imply that societies with large numbers of skilled workers will have lower ethical standards than others. But this is not the case. There���s little evidence that wealthier nations, which have higher human capital, are in aggregate less moral than poor ones. In fact, I strongly suspect the opposite: richer nations are more tolerant and less crime-ridden than poorer ones. I���d rather walk through the streets of Zurich at night than those of Lagos. This tells us that some other mechanisms offset the tendency for skills to diminish moral conduct. Ben Friedman and Deirdre McCloskey have described these.

March 10, 2016

Jarvis's poverty of ambition

In the Westminster bubble, Dan Jarvis���s speech this morning is being seen as a leadership bid. To me, however, his speech seems to embody the same ���poverty of ambition��� which he deplores.

One reason for this is that whilst he is entirely correct to point out that living standards were stagnating even before the crisis, he misdiagnoses the problem in perhaps two ways.

First, I fear he overstates the problem of corporate short-termism. Historically, stock markets investors have overpaid for "growth" stocks, which implies they have if anything been irrationally long-termist. And insofar as some companies are "focusing on the short-term buck rather than long-term value" this might be a rational response to immense uncertainty. I applaud Jarvis's call for a rejigging of corporate taxes to remove the incentive (pdf) to take on debt rather than equity, but it's not a solution to our fundamental problem.

My second problem is this:

New Labour didn���t see ��� with sufficient clarity ��� the downsides of globalization.

They knew it meant cheap consumer goods. But, they didn���t recognize that too often, it meant cheap labour too.

If "globalization" is intended to be a euphemism for "immigration", we can dismiss Jarvis immediately as a Daily Mail-pandering ignoramus. At worst, immigration has had only a slight impact upon the wages of the low-paid.

But let's give him the benefit of the doubt. Let's assume he is speaking in the intelligent sense, and referring to the factor price equalization theorem. This tells us that - for a country like the UK - globalization can reduce unskilled wages even without a single immigrant: this is because when we import those cheap consumer goods we are in effect importing cheap labour.

The question is: what to do about this. The answer isn't restrictions on free trade: Jarvis is right not to mention these.

But nor is it to increase skills and education. Even the most highly educated of our young people -doctors and investment bankers - are unhappy. This tells us that education is not sufficient.And if Frey and Osborne are right, even "good" jobs will become increasingly scarce.

Instead, the solution is for the state to raise the demand for less skilled work through expansionary macro policy to create genuine full employment and a serious jobs guarantee. However, whilst Jarvis talks, reasonably, about infrastructure spending and regional policy, he stops well short of these more radical options.

Jarvis claims that capitalism "should work as servant, not as master." But this fails to acknowledge Kalecki's point - that if the task of job creation is entrusted to capitalism, it will continue to be the master.

I fear, therefore, that Jarvis's speech is yet another example of centrist utopianism - the delusion that smallish tweaks to capitalism can transform the lives of the worst off.

March 9, 2016

Expertise in politics

Does the UK have the intellectual resources to take big policy decisions? I ask because of the reaction to Mark Carney���s evidence on Brexit to the TSC yesterday. Although his claim that Brexit would increase uncertainty is shared by most economists, Peter Bone (1���21��� in) and ��� more coherently ��� Tony Yates say he should wind his neck in.

This, though, runs into a problem. The Bank has the biggest collection of macroeconomic experts in the country. The Brexit debate ��� which is of pitifully low quality anyway ��� could only be improved by their involvement.

This is especially worrying because there are so few other informed voices. Many academic economists are too busy wrestling with managerialism and publication targets to play a role. Many of the better think tanks have a low profile. The state of Britain���s ���public intellectuals��� was summed up by Prospect magazine���s survey revealing that Russell Brand was voted the UK���s top ���world thinker���. And as for the media���

Worse still, the government is doing nothing to change this. If it wanted an informed debate about Brexit, it could have followed the example of Gordon Brown in the early 00s who commissioned weighty academic papers on whether the UK should join the euro*. But it hasn���t. Worse still, the absurd proposal to ban academics from lobbying might already be having a silencing effect.

Now, none of this is to say that Brexit necessarily should be judged on solely technocratic grounds. Steve is right to say that technocrats have their limits:

Wonks are the help. The role of the democratic process is to adjudicate interests and values. Wonks get a vote just like everyone else, but expertise on technocratic matters ought not translate to any deference on interests and values. If your theory of democracy is that informed citizens ought to cast votes based on the best social science, you have no theory of democracy at all.

But I fear that, in this case, we have the opposite problem: an under-use of wonks, rather than an over-use. This poses the risk that, whichever way the Brexit referendum goes, voters might be unpleasantly and unnecessarily surprised by what they get.

Luckily, I suspect that this risk is small: the stakes might ��� ultimately ��� be lower than people think. But if I���m right, this owes nothing to our political culture.

Underling the Brexit debate, therefore, is what might be a more important set of issues: what role should expertise play in politics? How best can that expertise be used? These issues, though, are being ignored. Which, of course, suits charlatans and third-raters perfectly well.

* Yes, he did so for support rather than illumination ��� but my point holds.

March 8, 2016

In defence of (some) economics

Alex Douglas says that economics ���makes very few successful predictions���: that ���nothing from economics has improved economic policy in the way that the integrated circuit has improved computing���: and accuses economists of making ���logical mistakes.���

I don���t intend to reject his claims, but I���ll give a counter-example from my day job. Back in the early 00s, I read Narasimhan Jegadeesh���s and Sheridan Titman���s paper which claimed that stocks which had risen in previous months tended to continue to rise. I interpreted this as a prediction ��� that momentum stocks would tend to out-perform in the UK. So I tested it. At the end of each calendar quarter, I took an equal-weighted basket of the best-performing shares* from the FTSE 350 to see how they would perform in the following quarter. And they have hugely out-performed. Since I began the exercise in 2004, UK momentum stocks have tripled in price, whilst the 350 has risen only just over 50 per cent.

Jegadeesh and Titman therefore made a successful prediction ��� and a useful one too. In fact, researchers have uncovered momentum effects pretty much everywhere they have looked: in commodities, currencies, international stock markets and sports betting.

This is not the only useful and successful prediction in financial economics. The efficient market hypothesis might be much derided (and the great performance of momentum stocks is exhibit A against it**) but it has made a prediction ��� that investors shouldn���t expect active managers to beat the market after fees ��� which has been successful.

Or to take another example, back in 1985 Hersh Shefrin and Meir Statman claimed (pdf) that investors lost money because they were too quick to sell winning stocks and too slow to sell losers. Subsequent research by Brad Barber and Terrance Odean has found that this prediction has also been right.

These, I would contend, are only a few of the ways in which financial economics has provided us with good practical advice ��� successful predictions, if you like.

All this raises the question. How come these predictions have been successful and useful when Alex claims otherwise?

One big reason is that (aside from the EMH) these predictions haven���t been derived in the way that Alex characterises economics ��� as logical deductions from theoretical principles. Instead, they were gleaned from a careful search for facts. Were Jegadeesh and Titman doing data-mining? I don���t give a damn: they discovered a useful and replicable result.

In fact, this is how economics in general has progressed in recent years: it has become increasingly empirical.

This is not to say that Alex is attacking a straw man. There are still some theory-driven, fact-blind economists lingering on. : I fear that some heterodox economists with their ambitious theoretical attacks upon ���mainstream economics��� fall into this camp as much as some dogmatic neoclassicals.

However, insofar as economics is useful and progressive, it is not because of the development of grand theories but because of humble fact-gathering. In economics, I am a hardline Blairite: what matters is what works.

* Initially I measured the best performers over the previous three months, but latterly over the previous 12. Consistent with Jegadeesh and Titman���s claim, it doesn���t much matter which you take.

** Exhibit B is the out-performance of defensive stocks ��� a fact which explains much of Warren Buffett���s success (pdf).

March 7, 2016

Advice to the young

In the FT, Lucy Kellaway criticizes Joseph Mauro���s advice to his juniors at Goldman Sachs who are thinking of leaving to join start-ups or go back-packing: ���put your head down and keep running���, he says. I think he���s right and she���s wrong ��� though not quite for the reasons Mr Mauro gives. If I were he, I���d suggest the following:

- Working at Goldmans is CV gold. You might think the work is mind-numbing. But outsiders don���t know this. Having Goldmans on your CV looks much better than having whoarethey.com. And five or ten years at Goldmans looks better on your CV than having it for a few months, which suggests that you couldn���t hack it. Signals matter.

- Start-ups aren���t an easy option. You���ll have to work long hours there too, and perhaps in no more supportive an environment, so don���t move in the hope of getting a better work-life balance. And there���s no guarantee of success: Goldmans is too big to fail, but start-ups aren���t. Many of them fail ��� and worse still ��� do so at the same time. That means you could be out of work in a few months��� time and competing against other talented people for scarce jobs with a wonkier CV than you���ve got now.

- In this context, staying at Goldmans is like holding a real option. In many cases ��� and especially in the case of uncertainty ��� you should hold onto your real options.

- The payoffs to working at Goldmans are long-term. If you live frugally and avoid taking on liabilities such as a wife and children ��� and if you���re working 80-hour weeks it���s hard to do otherwise ��� you should be able to retire in your late 30s. Or failing that, at least be able to find low-paid but satisfying work where you needn���t to worry about salary or career advancement. I know someone who did this. Ms Kellaway might be right that ���if you are in your 20s there are no obvious benefits of playing a long game���. But just because benefits aren���t obvious does not mean they don���t exist. They do, and they are considerable.

Now, I appreciate that nothing is more certain to be ignored than advice to the young from old farts. But in a sense, I���m not offering advice. Instead, I���m pointing to a fact about today���s capitalism ��� that it offers a raw deal even to the most talented or hard-working or luckiest young people. They cannot have a decent income (decent enough to buy a house anyway), job satisfaction and a work-life balance. They must choose. One good choice some of them can make is to regard capitalism as a burglar regards a house: grab as much as you can while you can, and then leg it.

March 6, 2016

Trump, & not seeing luck

I���ve long been puzzled by Donald Trump���s popularity ��� until the thought occurred to me, that one key to this perhaps lies in the TV show Deal or No Deal.

My befuddlement has not been that Trump is a right-wing git: history tells us that these often win support in hard times. Instead, it���s that his popularity grew after he insulted John McCain, even among the sort of people who usually revere war veterans.

George Lakoff takes us a step towards understanding this:

���Winning isn���t everything. It���s the only thing������Consider Trump���s statement that John McCain is not a war hero. The reasoning: McCain got shot down. Heroes are winners. They defeat big bad guys. They don���t get shot down. People who get shot down, beaten up, and stuck in a cage are losers, not winners.

This overlooks a fact which many of us think important ��� that the difference between ���winning��� and ���losing��� is often due to luck. McCain was a ���loser��� because he had the bad luck to be shot down in Vietnam. But that ill-luck should not detract from his character. As Kant said:

A good will is not good because of what it effects or accomplishes���Even if, by a special disfavor of fortune or by the niggardly provision of a step motherly nature, this will should wholly lack the capacity to carry out its purpose���if with its greatest efforts it should yet achieve nothing and only the good will were left (not, of course, as a mere wish but as the summoning of all means insofar as they are in our control)���then, like a jewel, it would still shine by itself, as something that has its full worth in itself.

This is where Deal or No Deal enters. That show demonstrates that people fail to distinguish between luck and merit; they have ���strategies��� even for what is a game of pure luck. To this mentality, Trump���s insult to McCain makes sense; he is indeed a loser. By the same token, Trump is a ���winner��� even though his wealth is due not to business acumen ��� he���d probably be even richer if he���d simply invested in tracker funds ��� but to the good fortune of the 70s property boom, a rich father and generous bankruptcy laws. His talents, such as they are, consist in self-promotion and for ���using the government as a hired thug to take other people���s property.���

It���s not just uneducated hill-billies who conflate luck and merit. For one thing, the US is not the only country in which an oddly-coiffed cunt from a wealthy family has achieved undeserved political popularity. And for another, experiments at universities in Barcelona and Singapore have found that even otherwise bright students are willing to pay people for a fictitious "expertise" in predicting the toss of a coin.

Sadly, though, the failure to distinguish between luck and merit doesn���t just help explain the hopefully brief and futile rise of a demagogue. It has longer-lasting pernicious effects. The narcissistic fiction of the rich that they owe their success to merit rather than to a lucky accident of being born in the right country leads to opposition to redistributive taxation. And supporters of immigration controls fail to see that the difference between ourselves and poor Mexicans or Syrians is due mainly to accidents of birth. In these, senses,as well as in their deference to the ���well-born��� Trump and Johnson, voters seem to think it right that people���s fates should be settled by where they were born.

Ironically, therefore, the failure of capitalism has led to the rise not of socialist attitudes but of feudalist ones.

Chris Dillow's Blog

- Chris Dillow's profile

- 2 followers