Chris Dillow's Blog, page 80

June 20, 2016

Vote Remain: a simple decision

At the start of the EU referendum campaign, I was mildly in favour of Remain. My position has changed. It is now strongly for Remain.

This is not another example of asymmetric Bayesianism. Had the debate been a high-minded one about the merits of the EU, my position would probably not have changed as it has. On the one hand, the work of John Van Reenen and colleagues has given me a stronger view of the flaws in the economic case for Brexit. But on the other, I take Andrew Lilico���s point that there are risks to staying in the EU and perhaps Brexit would help to improve the poor governance of the euro zone: the imposition of austerity onto Greece ��� and its support for bankers ��� shows that EU institutions are deeply flawed. Larry���s correct in saying that ���Europe���s economic model isn���t working.���

However, the debate is no longer between good reasonable people on both sides. It has become a matter of decency versus barbarism. The Leave campaign has ��� with some under-publicized exceptions ��� been one of the most disgraceful spectacles in modern British political history. Nick is entirely right to say it has ���poisoned rational debate���.

For one thing, it���s biggest claim ��� splattered over their campaign leaflets and buses ��� is a barefaced lie (pdf). EU membership simply does not cost us ��350m a week. Equally, the idea that Turkey will soon join the EU is also a lie. As Michael Dougan says, the Leavers are guilty of dishonesty on an industrial scale. Yes, some of the claims of Cameron and Osborne have been as stupid as we���d expect from such utter mediocrities but the bulk of downright lying has been on the Leave side.

It would, though, be wrong to say the Leave side is merely lying. Liars at least care enough about the truth to want to deny it. In other respects, however, the Leavers just don���t care about the truth. Farage���s claim that ���the doctors have got it wrong on smoking", Gove���s remark that people ���have had enough of experts��� and the overlap between high-profile Leavers and climate change deniers all tell us the same thing ��� that the Leave side contains a big element of crass anti-intellectualism.

And then, of course, there���s immigration. The slogan ���vote Leave, take control��� isn���t offering voters real control over their own lives ��� of the sort that would come with genuinely empowering policies such as worker democracy or a citizens��� income ��� but simply immigration controls. Leavers aren���t doing this because they���ve got good new evidence that immigration is bad for the economy or public finances ��� they haven���t ��� but simply because they are playing on people���s fears. They are stirring up xenophobia and racism, and diverting attention from the fact that stagnant wages and poor public services are due to austerity, the legacy of the financial crisis and the failures of capitalism, rather than to immigrants.

Of course, not all Leavers are anti-intellectual racist liars. But most anti-intellectual racist liars are on the Leave side.

Now, some of you have a vision of a Britain outside the EU that is a free, liberal, socialistic country. These are ideals with which I have sympathy. But we are kidding ourselves if we think a vote for Leave will be a move towards such a society. Instead, it���ll be a mandate for Farage and the inward-looking, reactionary mean-spirited philistinism he embodies. As Phil says:

If Leave wins, who wins? The most backward forces in British society do. The Europhobic Tory right, UKIP, and every two-bit racist outfit.

Usually, when I vote it is with misgivings: no political party fully represents my beliefs. On Thursday, however, this will not be the case. I���ll cast my vote confidently and proudly as a rejection of Farage and all he represents.

June 17, 2016

Against this referendum

The EU referendum raises a longstanding question in welfare economics discussed, for example, in this paper (pdf) by Daniel Hausman: why should we pay attention to people���s preferences?

The standard answer is that people know what is best for themselves -or at least that their mistakes cancel out ��� and so satisfying people���s preferences maximizes aggregate welfare. As Jeremy Bentham wrote, ���no man can be so good a judge as the man himself, what it is gives him pleasure or displeasure.���

However, whilst the idea that people are good judges is valid in some contexts, it seems assuredly untrue of the EU debate. There are three problems here*:

- Voters are wrong about the basic facts. For example, they over-estimate the number of EU migrants in the UK by a factor of three.

- Some of their views are shaped (pdf) by cognitive biases. A form of halo effect has bred hostility to ���elites���: because the Establishment has been wrong about many things, voters don���t trust them even when they correctly warn of the costs of Brexit. The post hoc ergo propter hoc fallacy means voters over-estimate the costs of immigration, and blame immigrants for problems caused by the financial crisis and austerity ��� a process perhaps exacerbated by the ���bad begets bad��� heuristic: voters unsettled by the uncertainty caused by immigration also believe immigration is bad for the economy. And people���s tendency to take risks when they have lost can cause them to become reckless.

- Many voters are simply angry and spiteful. 61% say they���d accept a weaker economy as the cost of reducing immigration**. As Dan Davies tweeted, we are a nation of 60-year-olds in crap towns complaining about GP appointments.

The problem is that these defective preferences are systematic. It is those who have lost from economic and social change, or who feel discomfited by it, who are most hostile to the EU.

Now, in saying all this I am not necessarily opposing referendums generally. In principle, it should be possible to have institutions which promote deliberative democracy, in which the public have a voice whilst ill-informed or nasty preferences are filtered out.

However, our referendum contains no such filters. Quite the opposite. Much of the media seems to be actively selecting in favour of the worst arguments. The BBC, to its shame, is complicit in this. Not only are its main reports impartial between lies and truth, but it also gives the oxygen of publicity to charlatans and anti-democratic neofascists rather than more thoughtful Brexiters such as Daniel Hannan or Andrew Lilico.

Herein lies a paradox. David Cameron set up the ���nudge unit��� because he was aware that people are sometimes irrational. And yet in calling a referendum he has unleashed the worst irrationalities of many voters.

As I write, we don���t know the precise circumstances that led to the murder of Jo Cox. But we do know that nasty rhetoric can have nasty consequences. I suspect that heightened anti-immigrant sentiment means that foreigners feel less safe walking our streets. Such insecurity is the direct result of Cameron���s decision to use a referendum in a ��� perhaps ill-judged ��� attempt to solve what is primarily a problem of internal Tory party politics. For this, he deserves our contempt.

* There might be a fourth: that some people's preferences are more intense than others. I'm leaving this aside.

** Far fewer are willing to pay a personal price, but this might be another example of a cognitive bias: wishful thinking leads folk to think that the costs of a weaker economy won���t be paid by them personally.

June 1, 2016

The centre-left's failure

Simon Wren-Lewis laments the failure of the centre-left to offer a radical response to the financial crisis, the legacy of which is of course still with us. This raises a paradox ��� that the centre-left is weaker politically than intellectually.

What I mean is that there is, in principle, a reasonable centre-left economic programme. This would include:

- A defence of immigration, pointing out that perceived pressures on wages and public services are, largely, illusions. It���s austerity to blame for these, not (for the most part) immigration.

- Redistributive taxation. Tax credits, financed by taxes on land and inheritance are both egalitarian and efficient.

- Financial sector reform. Demanding higher capital requirements for banks, for example, isn���t especially radical. Nor are policies to ensure better funding of entrepreneurs, as Liam Byrne has advocated (pdf).

- Public sector reform (pdf), on the grounds that it���s more necessary to increase efficiency when these cannot be so generously funded

- Policies to raise productivity. These would include infrastructure investment, better schooling especially in early years and investment in R&D.

We all have opinions on this sort of programme. But it would be a reasonable, coherent (if for me incomplete) offer. Hence the paradox ��� that the centre-left is weaker politically than it need be intellectually.

Why? Simon touches on the answer when he decries the centre-left���s obsession with ���electability��� ��� a word that has become a whine of over-entitled narcissists.

This, though, is part of a bigger problem with the centre-left. It failed to truly mobilize radical opinion; a good gauge of this being the fact that Labour party membership more than halved between 1997 and 2010. Yes, Blair won three elections. But this owed much to useless opponents; a growing economy which bought off opposition to immigration and allowed for improved funding of public services; and to short-term spin-doctoring which people now see through.

There���s long been a debate on the left about the efficacy of the parliamentary versus extra-parliamentary roads to socialism. The collapse of Blairism as political force has shown that a purely parliamentary approach is destined to fail. You can���t become a lasting, successful political force if you never leave the Westminster bubble. As Phil says:

Cocooned by parliaments, cushioned by the media, and swaddled by self-importance, [the centre left] never saw the insurgency coming, and it���s that lack of foresight that condemns them to the political wilderness.

It would, however, be wrong to draw a sharp dichotomy between policy ��� which as I���ve said looks attractive - and strategy. New Labour���s disregard for mass popular, grassroots politics was part of a wider intellectual defect ��� an excessive faith in hierarchies and ���elites���. Gordon Brown, for example, consistently praised bank bosses as leaders and wealth creators, and invited them into government. And the emphasis upon target culture and managerialism meant that New Labour demoralized and disempowered precisely the people whom it should have empowered ��� frontline public sector workers.

Herein. I think, lies the reason for the weakness of the centre-left. The financial crisis was, to a large extent, a failure of top-down organizations. It therefore undermined a core belief of statist, hierarchical New Labour.

A radical response to the crisis requires that ���elites��� be challenged. New Labour and its epigones are unable to do this.

May 31, 2016

Rational consumers

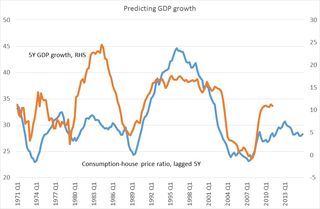

In the day job, I point out that the ratio of consumer spending to house prices has done a reasonable job of forecasting medium-term GDP growth, and that right now it is pointing to weakish growth.

Granted, this might in part be because of the denominator. When house prices are high ��� a low ratio in my chart - they subsequently fall and this depresses GDP via collateral effects (pdf) if nothing else.

But there might be something else going on. Consumer spending should be forward-looking. If so, low spending will be a sign that consumers expect bad times. And it���s possible that, across millions of consumers, errors in expectations will roughly cancel out: unless there are strong peer effects, the individuals who are wrongly optimistic will be balanced out by those who are wrongly pessimistic. To the extent that this is the case, aggregate spending will predict economic growth.

This shouldn���t strike you as outlandish. In the same spirit, Sydney Ludvigson and Martin Lettau have shown that consumer spending can predict (pdf) equity returns in the US, and Bank of England economists have corroborated this in the UK (pdf).

In fact ��� given economists��� inability to foresee recessions ��� it���s possible that consumers, in aggregate, are better economic forecasters than the professionals. Perhaps aggregate spending does what Friedrich Hayek claimed the price system does: it collects the dispersed, fragmentary and partial knowledge of millions of people into meaningful signals. Just as the decentralized price system embodies more knowledge than any central planner, so aggregate spending knows more than any centralized forecaster.

I don���t say this to make an economic forecast ��� though it���s worth noting that the consumption-house price ratio is sending a similar message to our record current account deficit. Instead, I do so to question the ���nudge��� agenda. This presumes (pdf) that wise and rational policy-makers can correct the follies of irrational lay-people. What we have here, though, is evidence that lay-people might (on average and in aggregate) know more than experts.

This is not the only evidence. The field of behavioural political economy ��� and, I guess, world history ��� reminds us that elites are as prone to cognitive biases as everyone else. As William Easterly has said:

Experts are as prone to cognitive biases as the rest of us. Those at the top will be overly confident in their ability to predict the system-wide effects of paternalistic policy-making ��� and the combination of democratic politics and market economics is precisely the kind of complex and spontaneous order that does not lend itself to expert intuition.

This is not to defend the simple-minded assumption that market agents are always rational. Instead, I suspect that irrationality, like intelligence, is context-specific: rational consumers (in my very limited sense of the phrase) might be irrational voters. The trick ��� in our personal lives as well as in economic research and policy-making ��� is to know when and how particular environments generate cognitive biases and when they don���t.

May 28, 2016

Labour's economic answers

Tony Blair says of the Labour leadership: ���These guys aren't providing answers, not on the economy, not on foreign policy.��� I don���t want to discuss foreign policy ��� others might have opinions on Mr Blair���s ability to judge that ��� but in economic policy, this seems questionable.

Among our economic problems are: persistently weak capital spending; a fiscal policy which, at the ZLB, cannot cushion the economy from adverse shocks; stagnant productivity and real wages; and unaffordable housing.

And Labour does have some good answers to these. A National Investment Bank can step up investment in new technology and infrastructure; Labour���s fiscal rule increases the flexibility of policy; the pledge to increase housebuilding is self-evidently a good idea; and McDonnell���s claim that ���there is a clear boost to the economy from worker ownership and management��� is correct; worker democracy can raise productivity.

Granted, Labour���s ideas aren���t fully worked out yet, but this is only to be expected four years from an election. The fact that McDonnell is seeking advice from top quality economists augurs well. As Liam Young says, Labour is building a good economic case.

This is not to say that Labour can solve all our economic problems. There���s not much it can do about the long-term slowdown in world trade growth ��� which is an especial problem as the current account deficit might become a constraint on growth. It doesn���t seem yet to have a policy about banks and financial stability (hint: nationalization). And it might be under-estimating the power of the forces depressing investment such as low profits; the fear of future competition and the possibility that companies have wised up to the fact that innovation doesn���t pay much.

However, I suspect that this is not what Blair has in mind; scepticism about the health of capitalism would be out of character for him. So what is he thinking?

One possibility is that he���s just out-of-touch. A globetrotting multimillionaire friend of dictators is not well attuned to the struggles of the low-paid, or to McDonnell���s attempts to solve them. Another is that he���s living in the world of post-truth politics, in which the test of policy is not whether it is a coherent answer to real problems, but simply whether it sells to a biased media and inattentive electorate. A third possibility is that he���s thinking of the economy in BBC mediamacro terms ��� as a synonym for ���government borrowing.��� None of these possibilities do him any credit.

May 27, 2016

Markets as selection devices

One of the stronger defences of free markets is that they act as selection mechanisms. To the allegations that stock markets aren���t efficient because investors are irrational or that firms can���t maximize profits because bosses don���t know what they���re doing, the reply is that this might be so, but the market eliminates egregious irrationality and selects for those firms that have stumbled upon profitable strategies.

This, though poses the question: how does selection really work? A new paper by Pascal Seppecher and colleagues at the University of Paris gives one answer. They show that selection can lead to ���wild fluctuations and deep downturns���. For example in good times, the market selects for companies who borrow to expand because these take market share from their cautious rivals. However, high leverage exposes firms to the risk of bankruptcy when an adverse shock occurs, which leads to a sharp downturn as they try to deleverage. You needn���t look far for an example of this; it describes banks behaviour in 00s.

The problem here is that, when faced with selection pressures, firms face a trade-off between what James March called (pdf) exploration versus exploitation. The firm that maximally exploits existing conditions will be maladapted when those conditions change. The firm that invests in exploring alternative strategies might survive change, but at the expense of not maximizing short-term profits.

To put this another way, the best chance of survival in a changing environment is to pursue mixed strategies. But these ��� by definition ��� do not maximize ���shareholder value��� in the short-run. And if all firms in an industry pursue the same strategy, we can have massive systemic instability, as the banking system showed us (pdf).

It���s not just change in the environment over time that can lead to maladaption, corporate death and downturns. A similar problem occurs when businessmen move from one environment to another. For example, the market in sportswear selected in favour of Mike Ashley���s ruthless cost-cutting. But that strategy when applied to Newcastle United proved less successful*. Or to take a more outlandish example, the market selects in favour of property developers who ���restructure��� their debts and dodge taxes. But it���s not so clear that such strategies are a good way of handling the government���s finances.

In fact, there���s another problem here: markets might select not for sensible behaviour but for lucky chancers. As Armen Alchian wrote in a brilliant paper (pdf) way back in 1950:

The greater the uncertainties of the world, the greater is the possibility that profits would go to venturesome and lucky rather than to logical, careful fact-gathering individuals.

This is surely true in financial markets. Bjorn-Christopher Witte has shown that risk-taking fund managers can attract more inflows and higher salaries than more cautious but better managers. Economists at Cass Business School corroborate this. They show that just six months of good performance (far too short a period to demonstrate skill rather than luck) can attract inflows into funds ��� and those funds go on to under-perform.

In a similar vein, Brock Mendel and Andrei Shleifer show that investor can chase (pdf) noise ��� a process which can give big profits to the irrational noise investor who bought over-priced assets early enough.

Now, in saying all this I don���t mean to reject the analogy between markets and natural selection. Quite the opposite. It���s a good one ��� especially but not only in financial markets. We should push it further, and ask: what exactly is it that the market selects for? How fierce is the selection process; the existence of a ���long tail��� of badly managed firms (pdf) suggests it isn���t always and swiftly brutal? And: how vulnerable are today���s survivors to the danger of a change in market conditions?

These answers will of course vary from market to market and time to time. But that���s the point. Economics is (or should be) an empirical discipline. Windy talk about ���optimality��� isn���t good enough. Sometimes, the invisible hand gets the tremors.

* Yes, Ashley did invest in the club last season, but that change came too late.

May 24, 2016

Prospect theory & populism

Does prospect theory help explain support for Brexit in the UK and for Donald Trump in the US?

The bit of the theory I have in mind is the prediction that people are risk-seeking when they are losing, because they gamble to get even. This explains several phenomena: why the favourite-longshot bias is stronger (pdf) in the last race of the day*; why (pdf) stock-pickers hold onto losing shares; why losing sports teams abandon their tactics in favour of risky all-out attack and ���Hail Mary��� passes; and why we sometimes get rogue traders ��� men who try to recoup losses by making riskier trades and so lose even more.

The same thing might explain support for Brexit and Trump. It���s generally agreed that both causes draw support from workers and the unemployed who feel that they���ve lost out under the existing order. As Jonathan Freedland says, ���the voters rallying to populist insurgents are those who feel failed by conventional politics, left behind either economically or culturally.���

Of course, voting for Brexit, Trump or other populists is risky. But prospect theory tells us that those who feel they���ve lost might want to take risks. This might be because they feel they���ve nothing to lose: the threat of higher unemployment isn���t so scary if you���re already unemployed or if you think there���s a high chance of losing your job anyway. And/or it might be because they think that change carries upside risk.

This mechanism is amplified by another ��� distrust. The elite���s warnings that Brexit and Trump are risky are true. But many poorer workers and unemployed don���t trust elites ��� a fact which Brexiteers are cynically exploiting.

My point here is the opposite of Janan Ganesh���s. He writes that Brexiteers are rich enough to be able to ignore the economics of Brexit. Whilst this is true of Boris Johnson and Nigella���s dad, it cannot explain Brexit's support among over 40% of voters.

You might object there that, in theory, there is another mechanism tying impoverishment to political attitudes ��� resignation. Often, the poor can be apathetic about politics. I���m not sure there���s a contradiction here. The poor can be both apathetic in the sense of not actively seeking positive political solutions to their plight, but also willing to take a risky option should it present itself.

I���m making two points here.

First, we don���t need to invoke xenophobia, small-mindedness or racism to explain the popularity of Brexit or Trump. Such support can also arise from decent people acting as behavioural economics predicts.

Secondly, what we���re seeing here is a cost of inequality. Unemployment, insecurity and low pay has generated constituencies willing to back risky options. And, as Eric Uslaner and Henrik Jordahl has shown, inequality breeds distrust so that even on those (rare?) occasions when elites are correct, many voters don���t believe them. Perhaps, therefore, support for Trump and Brexit are not so much diseases as symptoms of a wider malady.

* Some researchers, however, find (pdf) this isn���t statistically significant, at least in the US.

May 23, 2016

Bad arguments against Marxism

One of the problems with being a Marxist is that one is the subject of silly misunderstandings. Here are a handful of the bad arguments against Marxism I often see, and my replies.

���Don���t you realize central planning has failed?���

We do. But if you want to find people who still believe in central planning today, you should look not among Marxists but in company boardrooms. It���s bosses who believe complex systems can be controlled well from the top down, not we Marxists.

In fact, many of us point to the abundant evidence that worker (pdf) ownership and control increases (pdf) well-being and productivity (pdf) as evidence that a post-capitalist society is feasible ��� in the sense of one in which hierarchical inequality is replaced by more egalitarian forms of control and ownership. For me, central planning is not a part of socialism.

���How can you believe guff like the labour theory of value?���

Simple ��� because as an empirical theory (pdf), it actually (pdf) works well (pdf). Paradoxically, the theory might be true but irrelevant. John Roemer has shown that it is not necessary for the claim that workers are exploited under capitalism. Instead, he says (pdf), we can say that workers are exploited if they would be better off if they could withdraw from capitalism, taking with them their per capita share of the capital stock. On this conception, the question is: does capitalist rule increase wages (by more efficient organization) or depress them (by exploitation).

���You���re ignoring the fact that capitalism has lifted millions of people out of poverty.���

I don't. It has. And Marx ��� perhaps more so that his contemporaries ��� was aware of this. Capitalism, he wrote, ���has accomplished wonders far surpassing Egyptian pyramids, Roman aqueducts, and Gothic cathedrals���, ���has given an immense development to commerce��� and caused a ���rapid improvement of all instruments of production.���

However, to assume that this will remain the case is to commit the fallacy of induction. Marx also thought that there���d come a time when capitalist relations of production would become ���fetters��� upon growth. It���s possible ��� given the slowdown in growth ��� that developed economies have reached this point.

���Marxists are the enemies of freedom.���

Let���s leave aside the fact that this accusation often comes from supporters of political parties that have created over 5000 new criminal offences since 1997. What this ignores is that there is a big strand of libertarianism within Marxism: Marxists are far more sceptical about the benevolence of the state than social democrats, for example. As Jon Elster has written, Marx "condemned capitalism mainly because it frustrated human development and self-actualization." For us Marxists, one of the nastier features of capitalism is that it forces people ��� for lack of alternatives ��� into employment relations which are illiberal, coercive and demeaning. For us one challenge is to find ways of increasing people���s real freedom to live fulfilling lives. Such ways might not be compatible with capitalism.

���You want to impose a social engineering dogma onto people.���

No. Insofar as government has a role to play in the transition to socialism, it���ll be through a form of accelerationism or what Erik Olin Wright calls (pdf) interstitial transformation ��� encouraging and facilitating democratic libertarian egalitarian alternatives to capitalism. For example, a citizens income combined with a meaningful jobs guarantee would be a step towards real freedom, and might kill off the most exploitative forms of capitalism by allowing workers to reject bad jobs. Preferred bidding status might encourage the growth of coops. Credit unions and P2P lending could be encouraged as alternatives to banks. Forms of civic engagement could be encouraged on the basis that small forms of democracy will lead to demands for more. And so on.

In this sense, socialism might evolve as capitalism did ��� through an admixture of emergence and state intervention.

���You���re a bunch of utopians.���

In the sense that we believe that a better world is possible, we plead guilty. But we are not alone here. Non-Marxists who claim there���ll be big gains from managerialist policies are also guilty of a form of utopianism. A big reason why I���m a Marxist is that I���m a sceptic about that sort of utopianism, and doubt how far working people���s lives can be improved within the confines of a stagnant late capitalism.

���Marxism is a pseudo-science.���

This accusation often comes from people who believe in a form of mainstream economics which rests upon numerous unobservable entities such as the natural rate of interest, natural rate of employment, marginal utility and marginal product.

I suppose it is true for some definitions of ���science��� and some definitions of ���Marxism���. For me, though, Marxism comprises a set of theories which are reasonably consistent with some facts, for example:

- Technology affects culture. ���The mode of production of material life conditions the general process of social, political and intellectual life��� said Marx. This has been confirmed, for example, by the work of Jeremy Greenwood. If you want an example of Marxism at the BBC, the strongest is Radio 4���s The Digital Human.

- Class and power - in the sense of access to the economic surplus ��� rather than human capital determine inequality

- Apparently free markets ��� what Marx called ���the realm of liberty, equality and Bentham��� ��� can disguise rent-seeking and exploitation. Marx had in mind the labour market. Other examples are the markets for CEOs and for many financial ���services.���

- Marx thought that capitalism produced a form of false consciousness; people failed to see its exploitative nature. I suspect a lot of the work on cognitive biases is consistent with this.

- Marx thought there���d come a time when capitalist institutions ��� what he called the ���relations of production��� would act to restrain economic growth. ���From forms of development of the productive forces these relations turn into their fetters.��� Secular stagnation might be evidence that this is happening. For example, intellectual property laws might do more to increase incumbents��� profits than encourage technical progress. Bosses��� opposition to organizational change might mean that the full gains from IT have yet to be realized. And the difficulty of monetizing innovation might help explain the paradox that techno-optimism co-exists with low investment.

In these ways ��� to mention just a few ��� Marxism is, to put it at its weakest, at least a useful perspective on today���s problems.

You might object here that my Marxism is idiosyncratic. Certainly, it owes more to the Marx described by Jon Elster than to the one portrayed by Leszek Kolakowski. But frankly my dear, I don���t give a damn.

May 20, 2016

TV journalism: no place for Marxists

My first reaction to the news that Noreena Hertz is to become ITV���s economics editor was: isn���t she slumming it? Others, though, have asked whether a leftie can be trusted to report economics impartially.

On this question, Ben is of course right to say that the answer is: yes. I���d add that being a Marxist is actually a qualification for the job, in two senses.

First, some of us Marxists ��� unlike many of our opponents ��� are not spittle-flecked fanatics. Instead, our Marxism arises from a cool-headed scepticism about whether capitalism really can maximally advance living standards and real freedom for all. Such scepticism is a virtue in any proper journalist. And it���s surely a vast improvement on the churnalism and unthinking deference to the rich and powerful that passes for most of journalism today.

Secondly, we Marxists know that we are in a minority, so we know which of our opinions aren���t mainstream. This makes us much more aware of potential biases in our own thinking, and so able to slough them off when necessary. By contrast, ���mainstream��� reporters might be more prone to groupthink and so pass off their own opinions as impartial fact.

In this context, the problem with Ms Hertz is that she���s NOT a Marxist. I fear instead there���s a danger that she���ll import bien-pensant Primrose Hill dinner party sentiments into her reporting.

Rather than ask: are Marxists fit to be impartial TV journalists ��� to which the answer is obviously yes ��� we should turn the question around and ask: Is TV journalism a fit job for any intelligent, sceptical person? I suspect not - at least in economics - for three reasons:

- Impartiality has come to mean not impartiality between economists but rather impartiality between politicians. This leads to systematic biases in reporting on subjects such as austerity, Brexit or immigration because the consensus of economists is not adequately conveyed.

- The news agenda, being set by politicians, is also biased. Non-problems such as ���the nation���s finances��� get attention whilst real economic issues such as low trend growth, the collapse in productivity growth and capture of the economy by the 1% are under-reported. I'm not sure how far one can fight this bias.

- High-profile reporters come under pressure from hysterical bigots. One of the big reasons why I work at the IC is that my readers ��� unlike those of newspapers ��� want good economics rather an echo chamber for their own neuroses.

It was pressures such as these that forced Paul Mason out of the industry. Perhaps, on reflection, my immediate reaction was right: the job is beneath Ms Hertz.

May 19, 2016

Farage's argument for Remain

Nigel Farage���s demand for a second referendum if Remain wins has met with the same reaction with which the famous heckler at the Glasgow Empire greeted Mike and Bernie Winters: ���Och, Christ. There���s two of ���em.*��� In fact, though, it has a serious implication ��� it means undecided voters should vote Remain.

The reason for this is simple. If Mr Farage gets his way then if you vote Remain and regret it, you���ll have a chance to change your decision. If, however, you vote Leave and regret it, you���ll have to live with your regret; nobody is proposing a re-match in this case.

If you regard both possibilities as equally likely ��� as I guess many undecideds do ��� then voting Remain is obviously the thing to do. It gives you a chance to change your mind whereas voting Leave does not.

To put this another way, if you vote Remain you retain an option to leave. But if you vote Leave, you have no such option: your choice is irreversible. Common sense ��� and real options theory if you want to be fancy ��� thus says that undecideds should vote Remain. Remain plus an option to leave is, for anyone roughly undecided, a better choice that Leave with no option.

For me, this is one of the strongest arguments for Remain that I���ve heard. (It���s so powerful that it should lead to such a strong Remain vote that even Mr Farage won���t demand a re-match, but let���s leave aside this paradox.) The fact that it comes from an ardent Leaver only confirms my prior, that the Brexit debate is characterized by a lot of counter-advocacy.

* Other accounts have a more realistic description of Glaswegian argot and the Winters��� talents.

Chris Dillow's Blog

- Chris Dillow's profile

- 2 followers