Chris Dillow's Blog, page 86

February 18, 2016

Debt, & ideology

Is high personal debt a threat to the UK economy? Vince Cable thinks so. He told radio 4 yesterday (9���28��� in):

A sudden change in household confidence ��� people beginning to get alarmed about their debt levels ��� could trigger a serious downturn.

This is a more ideological claim than you might think.

First,some economics. As Simon says, the question of what is the right level of debt is a very tricky one, not least because so much depends upon the distribution of debt. In fact, it���s possible that high consumer debt far from being a bad thing is in fact to be welcomed, because it���s a sign that households might be rightly optimistic about the future.

What���s more, history tells us that consumer-led downturns are quite rare. Since data began in 1955, there have been 45 calendar quarters in which real GDP fell. In only 11 of these did consumer spending fall by more ��� and several of these were in response to increases in sales taxes (1968Q2, 1975Q3 and 1979Q3) interest rates or oil prices (1980Q4). It���s rare therefore for an exogenous drop in consumer spending to trigger a recession. More often, consumer spending acts as a stabilizing force.

Recessions are far more often due to errors by those in power than to consumers: policy-makers setting interest rates wrongly; corporate bosses investing too much and then retrenching; or bankers cutting credit after making bad loans.

This is why I say Cable���s claim is ideological. In inviting us to worry about the alleged irrationalities of consumers, he is deflecting attention away from what has more often been the threat to our prosperity ��� the errors of our rulers*. In this way, a question that might undermine the legitimacy of the rich and powerful ��� do bosses, banks and policy-makers know what they are doing? ��� is not asked.

From this perspective, there���s a link with the fuss over Peter Tatchell being ���no-platformed.��� The kerfuffle over students��� wanting to limit cognitive diversity distracts us from a more pernicious form of no-platforming ��� the Westminster bubble���s narrowing of the Overton window to exclude many ideas from debate. It expects us to give a toss what a criminal associate thinks about Brexit whilst underplaying or ignoring more serious issues such as the cases for a citizen���s income or worker democracy or what to do about the UK���s lamentably low productivity.

What we see in both cases is a means of shoring up inequalities of power: fretting about consumer debt or silly student politics whilst underplaying the greater defects of the powerful help to legitimate the latter.

You might think I���m making a Marxist point here. Maybe. But I���m also channelling another classical economist ��� Adam Smith:

We see frequently the vices and follies of the powerful much less despised than the poverty and weakness of the innocent. (Theory of Moral Sentiments, I.III.29)

* In fairness, such errors might be occasionally inevitable because we can only have limited knowledge of complex emergent processes.

February 17, 2016

How much should millennials save?

The claim by Rebecca Taylor in the FT that ���today���s 25-year-olds need to save the equivalent of ��800 a month over the next 40 years to retire at 65 with an income of ��30,000 a year��� has met with much mirth. Perhaps Ms Taylor thinks millennials should sack one of their junior footmen to raise the cash.

Her claim embodies one of the things I hate about financial journalism ��� the tendency for advertising to masquerade as ���expert��� advice. A representative of the financial ���services��� industry wants us to hand over our money to that industry where a lot of it will disappear in management charges. There���s a surprise.

And guess what? Her claim is deeply questionable.

First, the maths. If you save ��800 per month in real terms then, assuming a real return of three per cent per year, you���ll end up with over ��720,000 after 40 years. An income of ��30,000 per year represents only just over 4% of this. Ms Taylor seems to be assuming some combination of low returns, a long retirement or a desire to leave a bequest. All are possible, but dubious.

So, should young people try to save? There are three reasons to do so:

- The power of compounding. If you start saving ��800 per month at 25, you���ll end up with over ��720,000 at age 65. But if you only start when you���re 35, you���ll end up with less than ��460,000. The first ��96,000 you save will therefore make you over ��260,000. This is because 3% per year compounds nicely over 30+ years.

- Your earnings might not increase with age, so you can���t bet on being able to save later. This isn���t just because robots might take your job. You might just want to jump off the treadmill. I���m earning less (in nominal terms) now than in my late 20s.

- Job satisfaction doesn���t increase with age. Sure, if you���re lucky you���ll be doing more interesting work. But this is offset by an increased awareness that life is short and hence that there are other things you���d rather do with your time. If you save when you���re young, you might be able to afford to retire early.

Against this, there are arguments against saving a lot:

- In extreme old age ��� when your health is gone - you can���t enjoy (pdf) your wealth so much. Holidays aren���t as much fun if your mobility is impaired, and fast cars are useless if your eyesight���s shot.

- You might not need as much as ��30,000 per year. This is well above median full-time earnings. And when you stop work, your expenses fall ��� eg on commuting, work clothes and eating at lunchtime. And we should, with luck, get over ��6000 a year from the state pension.

- There���s not much evidence that people saved too little in the past. The IFS estimates that most people approaching retirement have reasonable wealth: insofar as they don���t it���s because they were poor whilst they worked. And the ONS finds that older people are happier than others on average, suggesting that they at least didn���t save so little as to diminish their well-being. Granted, they benefited from rising house and share prices, which millennials might not enjoy. But this suggests that, if people weren���t irrationally spendthrift in the past, they might not be so today.

- Spending, like saving, can increase our future happiness. It can create happy memories, or a stock of consumption capital and leisure skills which allow us to better enjoy our retirement. As JP Koning says, consumption can be a long-lived asset.

- You might not live long. ���He who dies rich dies disgraced��� said Andrew Carnegie. He might have added that he also dies disappointed, as he missed on doing better things with money than saving.

On balance, the decision about how much to save is a tricky one, and probably impossible to get entirely right: we can save too much, as well as too little. This, I think, is one case for a decent state pension - it diminishes our need to make impossible decisions. Whatever the answer is, though, I doubt we���ll find it in the special pleading of vested interests.

February 16, 2016

Ronnie O'Sullivan & the limits of incentives

Ronnie O���Sullivan yesterday gave us a nice example of the limitations of basic economics. He turned down the chance to go for a 147 break because the ��10,000 prize for doing so was ���too cheap.���

This is an example of how incentives can backfire. Had there been no prize for doing so, I suspect O���Sullivan would have gone for the maximum, because he's a showman. Instead, he took umbrage at the meanness of the reward.

In this sense, he behaved just like the parents of children at the Israeli kindergartens described in a famous paper (pdf) by Aldo Rustichini and Uri Gneezy. They show that when the kindergartens introduced small fines for parents who collected their children late, the number of late-comers actually increased.

What happened in both cases is motivational crowding out: financial incentives can displace intrinsic ones. Small fines crowded out parents��� desire to help kindergarten staff by being punctual, just as a small prize pot crowded out O���Sullivan���s desire to play brilliantly. This is no mere curiosity. One reason for banks��� serial criminality ��� PPI mis-selling. Libor rigging, forex fixing and so on ��� is that bonus culture has driven out any sense of professional ethics.

Daniel Pink, author of Drive, has described this crowding out as ���one of the most robust findings in social science���: see this paper (pdf) by Edward Deci and colleagues or this by Bowles and Reyes for more evidence.

You might object that incentives only backfire in these cases because they are too small: O���Sullivan would have gone for the 147 if the prize were bigger.

However, big incentives can also backfire. The Yerkes-Dodson law says that people can become over-motivated and so ���choke��� under pressure: other work by Uri Gneezy has established this experimentally. Who can forget John Terry���s penalty miss in the 2008 Champions League final? (And who would want to?)

These are not the only ways in which incentives can fail. There are others:

- Performance-related pay can encourage people to hit targets at the expense of the organizations��� wider goals. If teachers ���teach to the test��� they might fail to instil in children a love of learning, and if bosses are incentivized to hit quarterly earnings��� targets they abandon longer-term strategy. For a formal model of this, see Benabou and Tirole (pdf).

- They can lead to figures being manipulated or fiddled.

- They can encourage a tunnel vision and so reduce (pdf) creativity. As Pink says:

Rewards, by their very nature, narrow our focus��� Rewarded subjects often have a harder time seeing the periphery and crafting original solutions. (Drive p44-46)

- Big bonuses can signal that the task is very difficult, or even impossible. This might demotivate existing staff, or have adverse selection effects, insofar as only irrationally overconfident people will apply for the job.

- Bonuses can encourage people to free-ride on others��� efforts. They can also encourage slacking, if workers give up after they have met their targets, or excessive risk-taking as workers become desperate to meet their targets.

Tim Worstall is right to say that the core concept in economics is that incentives matter. However, they can matter in unpredictable ways.

The point here is a simple one. Designing incentives ��� in companies, sport, public services or wherever ��� require careful thought. More thought, in fact, than is often given. I fear that, in the real world, ���incentives��� in fact serves an ideological function described by George Carlin:

Conservatives say if you don���t give the rich more money, they will lose their incentive to invest. As for the poor, they tell us they���ve lost all incentive because we���ve given them too much money.

February 11, 2016

Should we nationalize banks?

Should banks be nationalized to protect shareholders?

What I mean is that banks are risk-magnifiers. When they lose money, credit to the whole economy gets choked off, thus causing recession. Banks are critical hubs in a network economy.

Put it this way. In the 2008 financial crisis, the US���s biggest financial institutions lost between them less than $150bn. But during the tech crash of 2000-03 investors in US stocks lost over $5 trillion. The former led to a great depression, the latter to only the mildest of downturns. Why the difference? One big reason is that losses are easier to bear if they are spread across millions of (mostly unleveraged) people, but cause real trouble if they are concentrated in a few leveraged strategically important institutions.

One reason why non-financial stocks have fallen recently is that investors fear a repeat of 2008 ��� a fear which is all the greater because banks are so opaque. Yes, the bosses of Deutsche and Credit Suisse claim that they are sound ��� but nobody believes bosses these days. As Nicholas Taleb said, bankers are ���not conservative, just phenomenally skilled at self-deception by burying the possibility of a large, devastating loss under the rug.���

I suspect the CAPM has got things backwards. It says that banks fall a lot when the general market falls because they are, in effect, a geared play upon the general market. But sometimes, the market falls because banks fall.

Which leads me to the case for nationalization. This wouldn���t prevent banks losing money: these are inevitable sometimes because of complexity, bounded rationality and limited knowledge. However, when banks are nationalized, their losses would create only a very minor problem for the public finances as governments borrow money to recapitalize them*. That needn���t generate the fears of a credit crunch or financial crisis that we���ve seen recently. In this sense, nationalization would act as a circuit-breaker, preventing blow-ups at banks from damaging the rest of the economy. (Given that countries are exposed to financial crises overseas, the full benefit of this requires that banks be nationalized in all countries).

You might reply that the same effect could be achieved by demanding that banks were better capitalized, as Anat Admati and Martin Hellwig have argued: calls for 100% reserve banking are to a large extent just an extreme version of this.

However, the former would require massive share issues, which would themselves hurt stock markets. And the transition to the latter ��� as even its advocates acknowledge - would be complex: in fact, Frances has argued that it would kill off commercial banking. Nationalizing banks would be simpler.

You might object that doing so would impose losses upon shareholders, and the adverse wealth effects would depress demand. I���m not sure. By reducing the chances of future financial crises, the risk premium on non-financial stocks should fall, causing their prices to rise. And to the extent that banks have a positive net present value at all, their transfer to the public sector represents not a loss of wealth but a mere transfer: what bank shareholders lose, the tax-payer gains. The only wealth loss would come if banks are worse-managed in the public sector than they would be in the private ��� and that���s a low bar. Net, there might well be a positive wealth effect.

My point here is, however, a broader one. One fact illustrates it. During the golden age of social democracy ��� from 1947 to 1973 ��� UK real total equity returns averaged 5.1% per year. If we take the fall of the Berlin wall in 1989 as its starting point, they have returned 4.9% per year in the ���neoliberal" era. This alerts us to a possibility ��� that perhaps some social democratic policies are in the interests not just of workers but of shareholders too. Maybe the beneficiaries of neoliberalism are fewer than one might imagine.

* Because losses are most likely to happen when the economy is depressed, such borrowing would be done when demand for gilts is high and borrowing costs low. In fact, in such depressed conditions there might well be a case for quantitative easing, whereby the Bank of England buys the bond issues directly.

February 10, 2016

Costs of austerity

It���s not just public sector workers and benefit recipients who are suffering from fiscal austerity. So too now are bank shareholders.

The FT reports that the sharp fall in banking stocks so far this year is due in part to fears of more negative interest rates. This is because negative rates are in effect a tax on banks: banks have to pay the ECB and BoJ to deposit with it. JP Koning might be right to say that banks will eventually find a way of passing this tax onto others ��� say, by charging customers for deposits ��� but stock markets don���t agree with him (yet?).

The link between this and austerity should be obvious. Negative rates are a response to weak economic growth. But growth is weak because fiscal policy isn���t loose enough. A looser fiscal policy would prevent the need for negative rates, thus removing the potential pressure on banks��� profits.

In this sense, the costs of fiscal austerity are widespread. Not only do they fall upon public sector workers and benefit recipients, but they are also being suffered by savers who face nugatory interest rates and bank shareholders (and bankers themselves!) who are hit by fears of a de facto tax.

This poses the question: why isn���t this more widely realized? Why is anti-austerity seen as a minority left-wing position when it would in fact have wider benefits?

One reason, as I���ve said, is that people are lousy at making connections: they just don���t join the dots between fiscal austerity and low interest rates. And our illiterate media don���t help them.

A second reason is that anti-austerity comes as part of a package. A fiscal expansion might be good for bankers. But in many countries, this would come with policies they don���t fancy so much, such as higher taxes and more regulation. For some reason, right-wing anti-austerity isn't on the table.

A third possibility is Kalecki���s famous one:

Under a laissez-faire system the level of employment depends to a great extent on the so-called state of confidence���This gives the capitalists a powerful indirect control over government policy: everything which may shake the state of confidence must be carefully avoided because it would cause an economic crisis. But once the government learns the trick of increasing employment by its own purchases, this powerful controlling device loses its effectiveness. Hence budget deficits necessary to carry out government intervention must be regarded as perilous. The social function of the doctrine of 'sound finance' is to make the level of employment dependent on the state of confidence.

I confess to being unsure about this: do capitalists really prefer control over policy to economic stability? However, if you discount this possibility, we are left with an awkward question: why do so many people not favour policies which would seem to be in their own interests?

February 9, 2016

Are recessions predictable?

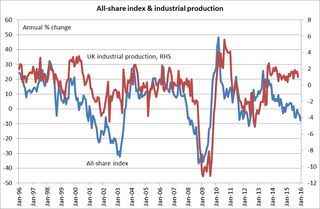

Amidst all the talk of a recession, this chart presents something of a puzzle. It shows that there���s a decent correlation (0.57) between annual changes in the All-share index and in UK industrial production*.

The puzzle is that this correlation is contemporaneous. If stock markets anticipated recessions and booms, we���d expect to see the blue line move in advance of the red one. But this isn���t really the case**. Sure, the strongest correlation (of 0.68) comes if we lag industrial production four months. But such a short lag might exist simply because the stock market is a ���jump��� variable whereas output isn���t. Shares can respond immediately to bad news (such as the collapse of Lehmans in 2008), but because output takes time and must be planned in advance, it can be slower to respond.

For longer lags, the correlation is weak ��� for example, it���s only 0.23 between price changes and output changes 12 months later.

This lack of a significant lead between share prices and output is especially surprising simply because you���d expect one simply because changes in share prices can cause changes in output ��� via cost of capital or wealth effects, or because share prices should send signals about future economic conditions.

So, what explains it?

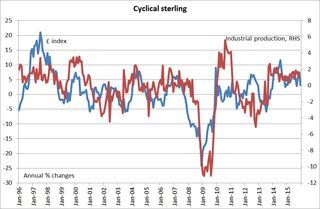

I don���t think the story here is about equities: my second chart shows a very similar relationship between output and sterling���s trade-weighted index.

Instead, all this is consistent with a simple possibility ��� that stock markets just don���t see recessions coming (or at least don���t anticipate the things that trigger recessions). We know that economists have consistently failed to foresee recessions. Perhaps this isn���t (just) because of their own inadequacies. Maybe it���s because economic fluctuations are inherently unpredictable.

This could be because recessions are the product of complex emergent processes. But there might be a more mundane reason. If some recessions were predictable, policy-makers would loosen policy in advance, thus preventing them***. The only recessions we ever saw would then be the unpredictable ones.

The message I take from this is that we should be humble about our ability to foresee recessions coming, especially when others aren���t expecting them.

* Given that UK equities are correlated with overseas ones, and UK industrial production with global output, I suspect a similar pattern is true generally.

** The chart is also inconsistent with Samuelson���s quip that the stock market has predicted nine of the last five recessions. If this were the case, we���d expect to see some falls in share prices which aren���t followed by falls in output. However, except in 2003 (and maybe now!) we haven���t.

*** They would then be criticized with hindsight for loosening policy unnecessarily!

February 8, 2016

Are football tickets under-priced?

Saturday���s protest by Liverpool fans at the proposed rise in ticket prices poses a puzzle - that from the point of view of elementary economic theory, football tickets are too cheap.

What I mean is simple. Fans are addicts; many would pay much more to see their team. Demand is therefore price-inelastic. And despite playing indifferent football, Anfield ��� like most Premier League stadia ��� has been full this season. Both these facts suggest that Liverpool���s owners could increase profits by charging fans more. Econ 101, therefore, tells us that tickets are under-priced.

This is not just true for Liverpool. A survey (pdf) by Anthony Krautmann and David Berri has found that most fans in many popular sports pay less for their tickets than conventional economic theory would predict.

Which poses the question: are team owners therefore irrational?

Not necessarily. There are (at least?) four justifications for such apparent under-pricing.

First, say Krautmann and Berri, owners can recoup the revenues they lose from under-pricing tickets by making more in other ways: selling programmes, merchandise and over-priced food and drink in the stadium.

Secondly, Shane Sanders points out that it can be rational to under-price tickets to ensure that stadia are full. A full ground and vibrant atmosphere, he says, increase a team���s chance of winning and thus increases future revenues. One way in which this happens is that referees are biased towards home teams with big crowds: we all know there is such a thing as a ���Stretford End penalty��� (aka a fair tackle).

Thirdly, higher ticket prices can have adverse compositional effects: they might price out younger and poorer fans but replace them with tourists ��� the sort who buy those half-and-half scarves and should, therefore be shot on sight. This increases uncertainty about longer-term revenues: a potentially life-long loyal young supporter is lost and a more fickle one is gained. It also diminishes home advantage: refs are more likely to give dodgy decisions in front of thousands of screaming Scousers than in front quiet Japanese tourists.

Fourthly, high ticket prices can make life harder for owners. They raise fans��� expectations: if you���re spending ��50 to see a game you���ll expect better football than if you spend just ��10: I suspect that a big reason why Arsene Wenger has been criticised so much in recent years is not so much that Arsenal���s performances have been poor but because high prices have raised expectations.

This imposes several costs on owners. Impatient demands to sack managers force them into difficult decisions. Fans��� protests can be bad for the owners��� ���brand���. And even the thickest-skinned owner doesn���t like having tens of thousands of people shouting abuse at him: even Mike Ashley has felt compelled to spend money at Newcastle United this season.

In these ways, apparently irrational behaviour ��� the under-pricing of tickets ��� might not, in fact, be so irrational after all.

Sometimes, what looks like irrational behaviour turns out to make sense if we consider agents��� motives and incentives more carefully.

The point, I suspect, broadens. To take just one example, the great performance of momentum and defensive stocks makes it appear that fund managers��� have, stupidly, left money on the table. However, when we consider that such stocks expose them to benchmark risk ��� the danger of under-performing their peers and so getting sacked ��� their behaviour becomes more understandable.

Apparent departures from rational behaviour should not lead us to immediately decry stupidity. They should instead be cues to investigate further why people are behaving as they are. This, of course, is true for life as well as economics.

February 6, 2016

On recommended reading

Diane Coyle���s question ��� what should the well-read student read? ��� has prompted some good answers, not least her own. But for me it raises a question: are there some classic books which are age-specific ��� which youngsters might love but older folk not, and vice versa?

Here are two examples from my sixth-form years. For my English A level, I had to read Middlemarch. It inspired me ��� to drop my plans to study English at university. God it was turgid. But it���s quite possible that its themes of disappointment and mediocrity would chime better with the middle-aged ��� though I���ve yet to summon the appetite to find out.

Then my history teacher, seeing that I was a gobby socialist (what ��� you���re surprised?) urged me to read Hayek���s Constitution of Liberty. His motives were entirely correct: one must read to challenge one���s prejudices, not confirm them. But I couldn���t get to grips with it. Maybe Hayek���s key insight ��� that our knowledge is tightly bounded ��� can only be learned properly at the School of Hard Knocks and formalized by reading after that bitter experience. Perhaps some things can���t be understood by cocksure youngsters, and nor should they be.

I suspect that two other writers I admire ��� Michael Oakeshott and P.G. Wodehouse ��� would have left me cold had I tried them when I was young.

The converse is also true. Some books are more suitable for youngsters. To a certain type of 16-year-old, Thus Spake Zarathrusta is a fantastic read. The older reader, however, thinks that someone should have had a quiet word with Mr Nietzsche. I suspect the same goes for Ayn Rand.

And I remember reading Crime and Punishment in almost one sitting as a teenager. But I was disappointed when I re-read it in older age (The Brothers Karamazov, on the other hand, remains my favourite novel.)

This thinking leads me to two principles that should inform our suggestions for what bright young people should read.

One is that readability matters. Books, at that age, should be fun to read. For me, this makes Diane���s suggestion of Hume���s Enquiry Concerning Human Understanding a brave one: it might work brilliantly, but might not. I���d also quibble with her recommendation of Kahneman���s Thinking Fast and Slow. Much as I admire his work, and think behavioural economics and cognitive biases very important, I found the first few chapters of that rather dull. I���d prefer to recommend Dan Ariely���s Predictably Irrational, which is a livelier read.

For the same reason, if I had to recommend a work of political philosophy, I���d plump for Nozick���s Anarchy State and Utopia on the grounds of readability. Most of you ��� and me ��� would find Rawls or Sen���s ideas more congenial. But let���s face it, they���re not exciting reads.

Young people will discover soon enough that most people ��� not least those who claim to be intellectuals ��� are tedious bores*. There���s no reason why they should learn this earlier than is necessary.

Secondly, books should alert youngsters to the breadth of ideas out there without necessarily flatly contradicting them. In my youth, Sabine���s History of Political Theory and Russell���s History of Western Philosophy did this. I like to think that Alasdair MacIntyre���s After Virtue might have a similar effect, with a twist, today.

You might object here that the books we should advise youngsters to read are those we agree with. I disagree. The point of education is not to turn out a generation of mini-mes. If your ideas are worth having, intelligent and curious young people will eventually discover them for themselves.

I must, however, caveat all this massively. I have little experience of young people: for obvious reasons, few people would me anywhere near them. My question to those who do have such experience is: how wrong am I?

* In their defence, this might (in a few cases at least) be because, as Isaiah Berlin said, there���s no reason to suppose that the truth, if it is ever discovered, will necessarily prove interesting. I worry that a lot of the advice I give readers in my day job is boring and repetitive.

February 4, 2016

Immigration, crime & jobs

Since the Cologne sex attacks, there has been even more of a backlash against immigration in Europe. Whilst the details of those attacks are unclear, I wonder: might increased crime be the price we must pay for doing our moral duty?

I ask because of a new paper from the CEPR (ungated earlier version here (pdf)) from Switzerland. It estimates ��� based on migration to Switzerland ���that:

Cohorts exposed to civil conflicts/mass killings during childhood are on average 40 percent more prone to violent crimes than their co-nationals born after the conflict.

This rings true. We know that people are scarred by experiences in their formative years and that there is an intergenerational transmission of violence. As Glen Bramley points out, British adults who are chronic offenders ���had very high instances of adverse childhood experiences���. It is surely, therefore, plausible that people who suffer the trauma of civil war and mass killings in their early years will themselves be disproportionately predisposed to violence.

But these are precisely the people we have a duty to help. The principle of luck egalitarianism tells us that it is unjust for people to suffer through no fault of their own ��� and it is not one���s fault if one suffers mass violence in one���s childhood. To condemn people to suffer because of a misfortune of birth is to revert to feudalism.

From this perspective, the claim that migrants are prone to violence ��� far from being a reason to exclude them ��� is in fact a reason for letting them in. It is those who have been most traumatized in their youth that we have a duty to help ��� but equally, it is these people who are prone to violence. If our immigration policy is at all humane, it will increase the domestic crime rate.

You might reply that our duty to help the world���s most traumatized people is trumped by a duty to reduce the threat of crime to ���our own people.��� Nations, however, are imagined communities. It is not self-evident that our duties to our co-nationals outweigh our duties to the very worst-off: the claim that they do requires cool-headed philosophical argument, not hysterical populist shrieking.

In this sense, we have a fundamental trade-off - between a duty to rescue people from civil wars and mass violence on the one hand, against curbing crime on the other.

But this trade-off can be mitigated. The very fact that violent crime has fallen in many western nations since the 1990s tells us that cycles of violence can be broken. The way to do so is to give work to asylum-seekers: common sense tells us that men are less likely to commit crime if they have something to lose (such as a job) by doing so. In fact, that Swiss research finds that:

getting labor market policies right can wipe out any crime-fuelling impact of past exposure to conflict.

Wouldn���t this (slightly) bid down the wages of native workers? It wouldn���t, if it were accompanied by serious full employment policies. Perhaps, then, proper macroeconomic policies have even bigger pay-offs than people think, as they would also help reduce anti-immigration feelings.

February 3, 2016

"Unelectable"

There���s one increasingly common meme I find very irritating: the dismissal of politicians as ���unelectable���. Corbyn has long been tagged such, as are most US presidential candidates.

I���ve two beefs with the word.

One is that it presumes that elections are predictable. But they are sometimes not. Remember the old adage, ���oppositions don���t win elections; governments lose them���? What if we were to have another recession? Or if the Tories were to split themselves over Europe? Corbyn wouldn���t look so ���unelectable��� then. As Anne Perkins and Jacques have pointed out, Thatcher was regarded as ���unelectable��� in the 70s, by both Tory wets and the Labour party. Look how that turned out. Public tastes are unpredictable ��� especially given today���s anti-establishment attitudes. As Adam Kotsko says, ���electability is a ���purely speculative property.���

What I especially hate here is the pretence to knowledge, even in the face of contrary evidence. People who never foresaw a Tory majority or the rise of Corbyn continue to pretend that they have the foresight to declare Corbyn ���unelectable���: I don���t know whether Tim Bale���s self-awareness of his ���arrogance��� in doing this is admirable or not. What such people are ignoring is the wise warning of thehistorian:

Anyone who doesn't��� admit to doubt, imprecision, contingency - is a fraud. No-one knows exactly what has just happened, let alone what is going to happen. Nothing is as clear as politicians, newspaper columnists, banks, betting markets, even commercial economists want you to think it is. Everything is uncertain.

My second problem with talk of ���unelectability��� is that it betokens a sense of entitlement. It is usually outsiders who are ���unelectable��� ��� Thatcher, Corbyn, Sanders, whoever ��� and only rarely Establishment figures. There���s a presumption here that elections can only be won by particular types: youngish good-lookers who went to the right schools and universities and who don���t unsettle the Very Serious People. ���Unelectable��� can be used to close off debate, to shift discussion away from policy and towards pseudo-technocratic psephology. Too often, it is used by the Labour right to cover up their intellectual vacuum. As Peter Ryley says, all they���re offering is ���grisly managerialism.���

Now, I don���t say this to defend Corbyn at all. By all means attack his policies or association with the ���regressive left���: at least we can then have a debate. Just drop the word ���unelectable��� ��� unless, that is, you want to be seen as an over-entitled arrogant charlatan.

Chris Dillow's Blog

- Chris Dillow's profile

- 2 followers