Chris Dillow's Blog, page 90

November 26, 2015

Osborne's wage squeeze

In the 2009 Pre-Budget Report the Labour government proposed a rise in employers' National Insurance Contributions. David Cameron said the measure was a "jobs killer" and George Osborne attacked it as a "tax rise on jobs" that "will stamp out the green shoots and kill the recovery."

Yesterday, Mr Osborne announced his own tax rise on jobs by introducing an Apprenticeship Levy.

It is this, and not just the money the OBR has magically discovered behind the sofa, which is paying for his tax credits U-turn. It will raise the Treasury ��2.7bn in 2017-18 - very close to the ��2.9bn that the restoration of tax credits will cost it*.

This raises the obvious question: if higher NICs were "a jobs killer", why isn't the Apprenticeship Levy? It's not because of any difference in scale: Labour's NIC increase would have cost employers around ��2.4bn a year**.

Instead, it's because higher payroll taxes, such as employer NICs or the Apprenticeship Levy, don't much raise the cost of employment simply because they lead to lower wages instead. The incidence of payroll taxes falls upon workers. Back in 2010 I pointed to experimental evidence from Finland for this, and said: "higher employer NICs are highly likely to be passed onto workers in the form of lower wages than they would otherwise get." The OBR thinks the Apprenticeship Levy will have exactly the same effect:

The additional costs created for firms and workers by the Government���s introduction of the apprenticeship levy and ongoing auto-enrolment into workplace pensions ��� both of which are economically equivalent to payroll taxes ��� will largely be borne through lower wages (Par 3.70 of this pdf)

Lower wages for whom, though? It can't be the very worst-paid, as these will benefit from the rising living wage during this time. Instead, it is likely to be workers just above the living wage who will suffer: they lack the bargaining power that comes with high skill (or rent-seeking talent!) whilst also lacking protection from the living wage.

In this sense, Mr Osborne's measures will compress pay differences between the worst-paid and those just above them. This might actually exacerbate trends which are already under way because of job polarization.

This might not be a good thing. For one thing, it might increase resentment as those who consider themselves hardworking and mildly skilled suffer a loss relative to those "below" them: we mustn't under-estimate the desire of people to "preserve differentials" as they used to say in the 1970s. And for another, less wage compression at the lower end of the labour market reduces the potential for the less skilled to work their way clear of poverty.

I suppose one might argue that Mr Osborne's measures would tend to increase one form of equality. But I doubt egalitarians will congratulate him for this. And nor should they.

* Lines 1 and 23 of table 3.1 here.

** Table 1.2 of this pdf.

November 24, 2015

Two realities of Labour politics

Is Labour heading for "civil war"? Colin Talbot says yes. Simon says no. I'm inclined to agree with Simon. There has always been tension in the party between socialists and social democrats: "Labour is a broad church" is one of the oldest cliches in politics.

I suspect this tension is exacerbated today by the fact that there are two different realities: the reality of electoral politics as shaped by the MSM versus economic reality. For example:

- Political reality regards Osborne as competent on the economy; economic reality sees him as an anti-economist.

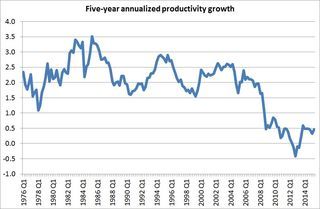

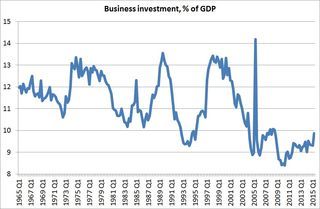

- Political reality sees the deficit as the top economic problem; economic reality sees low investment and productivity growth as bigger problems.

- Political reality requires austerity now; the economic reality is that this is failing in its own terms.

- Political reality sees benefit "claimants" as a drain on the economy: economic reality, arguably, focuses more on the possible damage done by the 1%.

- Political reality says immigration is a big problem; economic reality says it isn't.

- Political reality overstates the incomes of middle England; economic reality focuses on the fact that half of full-time workers earn less than ��528 per week and 90% earn less than ��54,000 a year.

There isn't that much substantive policy difference between John McDonnell's "socialism with an iPad" and Liam Byrne's "entrepreneurial socialism" (pdf). A much bigger difference, I suspect, lies in how to respond to these different realities. Leftists like me emphasize the economic realities, but rightists claim that a strategy of "no compromise with the voters" is electoral suicide.

Now, maybe I'm guilty here of deformation professionelle and am overweighting the importance of economics. Many of Corbyn's fiercest critics - I'm looking at you, Mr Cohen - focus instead upon his attitude to foreign affairs.

Nor must we under-estimate the role of personal loyalties. The division between Blairites and Brownites (which seems so quaint now!) was more about allegiances to individuals than about policy differences. Likewise, the strongest evidence for Corbyn being a hard leftist lies not in his economic policy - which is ho-hum and mainstream - but, as Colin says, in the fact that he has happily associated with some rum coves in (for example) the Stop the War coalition.

These caveats aside, what I'm saying is that in a better world Labour would find itself a new Blair - a leader capable of bridging the chasm between economic reality and electoral reality.

However, as Stephen says, nobody of such quality exists: the fact that Andy Burnham - who ran an utterly uninspiring leadership campaign - should be the most popular (pdf) alternative to Corbyn shows that Labour has not so much a talent pool as a puddle.

If we had a more sensible politics which was more collegial and less infected with the disease of leadershipitis, this wouldn't be so much a problem. In the real world, however, it is.

November 21, 2015

"A new economics"

"I've read everything ever written in economics, and I've decided it's all rubbish." John McDonnell probably didn't mean to say something this cranky, but it's one interpretation of his call for a "a new economics."

The thing is, Labour doesn't need new economics at all. For one thing, given that George Osborne is the anti-economics Chancellor, any economics at all would be an improvement.

And for another, pretty much everything substantive Mr McDonnell wants to say is consistent with old conventional economics. Anti-austerity is basic undergraduate economics. The case for a national investment bank is founded on the view that finance is dis-serving the economy - which is held by mainstream figures such as John Kay or Adair Turner. "People's QE" - the idea that the central bank should, if necessary, buy bonds issued by the state investment bank - is no more radical than the Federal Reserve's purchases of agency bonds. Concerns about under-investment can be rooted in the notion of secular stagnation proposed by Alvin Hansen in 1938* and revived by Larry Summers and Paul Krugman. And McDonnell's call for worker participation in management can be justified by Hayek's claim that centralized knowledge of complex systems is impossible and so there must be institutions for gathering dispersed information.

Mr McDonnell, therefore, has no need for "new economics". Some of the old economics is good enough to justify his policies. Which poses the question: why call for a "new economics"?

One possibility is that he's engaging in fake radical posturing of a sort that's too common on the left and is attacking a straw man - failing to see that there's a difference between economics and right-wing prejudices. Another explanation is that he is approaching the issue not from the perspective of an economist but from that of the Bubble which has perpetuated the illusion that there's some economic justification for what Osborne is doing.

Whatever the reason, Mr McDonnell is missing a big trick here. It is vitally important for any potential party of government to create the impression of economic competence. Labour should be kicking at an open door here: Osborne's policies have no basis in conventional economics and are failing even by their own dim standards. If, however, Mr McDonnell poses as a radical when he is not, he'll miss the chance to tell the truth - that it is Labour that is in many ways the party of mainstream economics and Osborne who is the crank.

* In fact, it's very similar to an even older idea - that of the stationary state, a theory held by most classical economists such as John Stuart Mill and his predecessors.

November 20, 2015

In defence of higher pensions

Is there a case for ever-rising state pensions which redistribute from young to old? Madsen Pirie thinks not. The image of pensioner poverty, he says, "does not accord with present day reality for most pensioners":

Some 86% of pensioners live in households with assets in excess of ��50,000. The average income of over 65s is ��15,400. A young person working on current minimum wage for a normal working week earns just under ��13,000. Yet the young person is taxed while the older person is guaranteed a triple locked pension.

However, you can easily argue that this is fair, and not just because, as Simon says, pensioners have assets because they have had years in which to save.

In fact, in one important respect pensioners are poorer than youngsters. Our wealth does not consist merely of financial assets. It also comprises human capital - our ability to earn wages. Youngsters have a lot of this: someone who can look forward to 30 years of a real income of ��25,000 has an asset of almost ��400,000, assuming a 5% discount rate. Pensioners have little or none.

This means they are exposed to greater risks than youngsters. For one thing, they face distribution risk: a shift in incomes from capital to labour would hurt them. Youngsters who hold a mix of human and financial wealth can diversify this risk, however*.

Also, oldsters have less chance to time-diversify. Youngsters can withstand short-term losses in the hope that better times will follow. Oldsters might be dead before they arrive.

And thirdly, younger retirees face a genuine uncertainty about whether equity returns will continue to mean-revert or not. Younger workers also face this risk, but their human capital means it is less important.

In these senses, older folk face more risk than younger ones. Higher state pensions can be justified on the grounds that they reduce the income risks that pensioners face.

And, remember, the triple lock does NOT merely redistribute to older people. Quite the opposite. Insofar as it stays in place, younger people will benefit more simply because they'll get many years of rises whereas an oldster will dies before getting them.And the power of compound growth is a great thing.

In saying this, I don't mean to deny that younger people have no grievances. They assuredly do. They face obscenely high house prices, the threat of being made redundant (pdf) by robots and the more immediate dangers of job degradation and polarization. There might be solutions to these harms - but they do not involve cutting pensions.

* Of course, many younger people can't afford to save and hold equities. This is either because they haven't yet seen the pay rises that come with experience, or because they'll suffer lifelong poverty. The first problem will solve itself with time, the second requires inter-personal rather than inter-generational redistribution.

November 18, 2015

Keynes' error

Why was Keynes wrong? In his 1930 essay (pdf), Economic possibilities for our grandchildren he predicted that:

the standard of life in progressive countries one hundred years hence will be between four and eight times as high as it is to-day.

This looks like being spot-on: real UK GDP per head is now 5.2 times what it was in 1930.

However, Keynes made another forecast that has been wrong - that the average working week would fall to around 15 hours. In fact, it is more than twice that. What's more, it is now falling much more slowly than it did in Keynes' time: in the last 20 years it has fallen by just 1.1 hours in the UK (3.3%) whereas in the 20 years to 1930, it fell by 8.25 hours (16%)*.

Why was Keynes so wrong about this? In a new paper, Benjamin Friedman suggests it is because of increased inequality. Since the 70s, he says, median incomes have grown much more slowly than mean incomes, so households have to work longer to get by.

Personally, I'm not so sure about this. Some of the longest working hours now are put in not by households on median incomes, but by those on high incomes, such as bankers and lawyers. This might well be due to increased inequality - younger bankers put in gruelling hours in the hope of joining the mega-rich 0.1% - but it's a different issue from the working hours of the median worker.

Instead, I suspect two other things have happened. One, as Friedman says. is that network effects have become more important. Now, more than in the 1930s, we want to spend more to keep up with the Joneses. The spread of TV might have exacerbated this process: there's evidence that this increases our material aspirations and reduces contentment with current income.

Another - which I can't quantify - is that technical progress has been more oriented towards consumption goods than Keynes anticipated. We want to work longer than he thought because there's more stuff to buy.

Both these theories are consistent with the fact that Keynes made another error. He thought that rising incomes would lead to bigger rises in savings. But in fact, the savings ratio has fallen in the last 30 years.

However, conventional economics - and indeed many forms of liberal democracy - tells us that, for policy purposes, we should take preferences as given. And many people's preference is to work longer hours. I'm thinking here not just of the unemployed and inactive but also of the 1.26 million people who are working part-time - Keynes' 15 hours a week - who want a full-time job. As Friedman points out, these preferences can best be met by more expansionary fiscal policy. It's a little paradoxical that some of the people who most strongly assert the importance of people's existing preferences - such as neoclassical economists and right-wing politicians - should be so loath to satisfy them in this regard.

* Source: Bank of England: three centuries of data, page 12.

November 17, 2015

Migration as poverty reduction

Immigration is a great way of reducing poverty. A new paper (pdf) by John Gibson at the University of Waikato and colleagues has established this in a neat way.

Each year, Tongans wanting to migrate to New Zealand are randomly given permits to do so. Comparing permit-winners who migrated to those who didn't win the ballot allows us to see the impact upon incomes of migration: because the ballot-winners, being drawn at random, are otherwise similar to the losers we get a relatively clean measure of the effect of migration.

Gibson and colleagues estimate that a ballot winner who migrates earns an average of NZ$340 per week, compared to NZ$126 for losers who stay in Tonga. That's almost a tripling of income. It amounts to a lifetime gain of well over ��100,000. Controlling for the difference in cost of living between Tonga and New Zealand doesn't much affect the results.

This is consistent with a finding by Orley Ashenfelter - that people doing the same job (working in McDonalds) earn ten times as much (pdf) in real terms in rich countries as in poor ones.

You might think this is trivial: people in rich countries are richer than those in poor ones - big deal. I'm not sure it is. The fact that incomes differ so much for similar people - ballot winners and losers or McDonalds workers - shows that such differences are due far more to the luck of where we were born than to personal qualities. We westerners often forget this: we were born on third base but congratulate ourselves on hitting a triple.

All this poses the obvious question: what right do we in the west have to deny others the chances that we got through the sheer good luck of being born in the right place? Does the one-in-a-millionish chance that a migrant might be a terrorist justify inflicting poverty upon tens of thousands of decent but unlucky people? Even if we concede that there are other costs to host countries - such as a loss of social cohesion and less internal redistribution - do these justify inflicting mass poverty? If so, how? As Bryan Caplan says, your love of your countrymen may tempt you to treat foreigners unjustly, but it's no excuse for treating them unjustly.

Of course, it's not just the impact of immigration upon rich countries that matters. So too does the impact on poor ones. Paul Collier has suggested that migration hurts these by depriving them of talented energetic people. But is this really an argument for migration controls? Forcing people to work within a particular country for substantially lower wages than they could get elsewhere is a form of slavery - more so than the high taxes of which right-wingers often complain.

I know the terrible Paris attacks might well cause a backlash against immigration. But this makes it all the more necessary to point out that there is a strong moral case for migration as a means of lifting people out of poverty. The question is whether morality trumps practicality, and if so why.

November 13, 2015

"Best practice"

David Cameron's letter (pdf) to Oxfordshire County Council has been widely criticized, but I fear there's one thing his critics are under-playing.

Cameron wrote:

I would have hoped that Oxfordshire would instead be following the best practice of Conservative councils from across the country in making back-office savings and protecting the frontline.

There's a big omission here. Cameron does not say exactly what "best practice" is - except for proposing asset sales, which as Mr Hudspeth points out (pdf) are "neither legal, nor sustainable in the long-term". Nor did he bother to say in which precise ways Oxfordshire Council was falling short of "best practice."

A Prime Minister who was serious about making efficiency savings would not have been so sloppy. Instead, he would have created a public register of "best practice" by councils around the country. Such a register would have two virtues:

1. Efficiency savings will be, in Sir Dave Brailsford's words, about the aggregation of marginal gains. Countless apparently mundane tweaks to procurement, administration and so on add up significantly. But councils have to know what these are. And they can do so by learning from others. Such a register would collate thousands of dispersed and fragmentary ideas from the 433 UK local authorities.

2. A public available register would bolster councils' incentive to adopt "best practice" as it would allow voters to benchmark their local authority against others.

We know from the work (pdf) of Nick Bloom and John Van Reenen that, in the private sector, there is a "long tail of extremely badly managed firms". I don't know if the same is true for public sector organizations - and nor, judging from the imprecision of his letter, does Mr Cameron. A register of best practice would tell us.

Rick might be right to say that "councils have already made most of the back office savings they can safely get away with". Again, a register would tell us.

I fear that what's going on here is more than mere incompetence, but two other things.

One is cargo cult management. Mr Cameron seems to think that "best practice" can arise magically merely by requesting it. This is not the case. It must be discovered and facilitated. Good leaders, in business or politics, know this.

Secondly, this corroborates my fear that Tory attitudes to spending cuts are putting the cart before the horse. A sensible strategy to cut spending would be one which "efficiency savings" were identified in advance of spending plans. Instead, spending cuts seem to be motivated less by a genuine desire to increase efficiency and more by an asinine macroeconomic policy.

Another thing: Mr Cameron seems to think "best practice" is confined to Conservative councils. This seems to me to be a level of political partisanship which verges on a mental illness.

November 10, 2015

Elites vs representation

Simon asks a good question: "why is there this presumption that we should be governed by a meritocratic elite?"

There are good reasons why we shouldn't be. One, as Simon says, is that in a representative democracy, politicians should represent the people*. This isn't merely an intrinsic good. Because we tend to trust people like ourselves, a more representative body of MPs might well increase trust in politics.

What's more, in one important respect, the "elite" aren't very good at politics. Jeremy Corbyn won the Labour leadership in large part because his Oxbridge-educated opponents were lousy at campaigning; being good at "insider politics" - for example winning influential mentors - doesn't make you good at appealing to "ordinary" people. As I've said, perseverance and soft skills matter at least as much as intellectual ability**.

Against these arguments stand the classic Burkean one - that MPs should not be representative of their constituents but should instead exercise independent judgement on their behalf.

We might elaborate on this by remembering something Thomas Sowell said:

One of the best things about going to Harvard is that, for the rest of your life, you are neither intimidated nor impressed by people who went to Harvard.

The intellectual (over-)confidence one gets from an "elite" university should help ministers to stand up against what Blair once called the "forces of conservatism": lobbyists, civil servants and other vested interests.

This argument for elite rule, though, doesn't apply now. For one thing, as Simon says, MPs can hire in people of good judgement, and even delegate policy-making to them - as it does with the Bank of England. And for another, Oxbridge rule has not generated good judgement. In several areas - such as immigration and fiscal policy - policy owes more to the prejudices of the mob than to enlightened judgement. And thirdly, politicians have not stood up against the strongest vested interests, such as those of financial capital: quite the opposite.

Which brings me to a depressing thought. Could it be that our present system gives us the worst of both "elite" rule and genuine representation? On the one hand, we get the lousy policies that mob rule would produce. But on the other hand, we also get the rent-seeking, distrust and narrowness of discourse that result from "eilte" domination.

* We should call this the Bill Stone theory. Simon Hoggart used to tell this story:

[Mr Stone] used to sit in the corner of the Strangers' Bar drinking pints of Federation ale to dull the pain of his pneumoconiosis. He was eavesdropping on a conversation at the bar, where someone said exasperatedly about the Commons: "The trouble with this place is, it's full of cunts!"

Bill put down his pint, wiped the foam from his lip and said: "They's plenty of cunts in country, and they deserve some representation."

** You might be tempted to add another argument in favour of representation and against elite rule - that it breeds a tendency to groupthink. I'm not sure about this. The most-criticized course - Oxford's PPE - isn't to blame here. As Nick says, "there wasn���t then, and is not now, anything resembling an Oxford ideology". A course which has produced Nick Cohen, Ann Widdecombe, Seumas Milne and David Cameron might have its faults, but the production of groupthink isn't one of them. The narrowness of political debate has other causes.

November 9, 2015

Lies we've told our children

The possibility of a strike by junior doctors has more profound political significance than generally realized.

What I mean is that we should regard Jeremy Hunt's proposal to change their working conditions as part of a general trend - resulting from both market and state action - for "good" jobs to decline in quality. This happened long ago to journalists, but we're seeing it among criminal lawyers where cuts to legal aid are depressing already-modest pay and among academics who face increasingly stressful demands to act as money-grubbers and coppers as well as intellectuals. And even the best-paid jobs in the City come at the price of long hours and mind-numbing tedium. As Rick says, "being middle class just ain���t what it used to be".

It's not just among what were once the most prized jobs that this is happening. Job polarization means there are fewer decent white-collar jobs for diligent but less academically able people.

And if Frey and Osborne are right, things could get even worse as some of these jobs are replaced (pdf) by AI and robots.

I say all this is significant because it undermines what has been the mindset of both Tories and New Labour. Tories have believed that a "free market" has offered able and hard-working youngsters the chance of better lives. New Labour thought that skill-biased technical change would increase demand for skilled workers - that we'd all become "symbolic analysts" - and so the economy needed ever more university graduates.

All this might have been correct once: there was for decades an upskilling of jobs which created an illusion of upward social mobility. But it is questionable now.

Young people used to be told: "do well at school and you'll get a good job."

But today, people who have achieved what was once the pinnacle of youngsters' ambitions - to become a doctor - are so discontent they are thinking of emigrating or striking.

The best we can tell our children now is: "if you do really well at school and university you'll be saddled with thousands of pounds of debt but you'll get a chance of working deadly long hours in a job that might eventually pay you well enough to afford a small flat in London."

It's not much of an offer. And a society that cannot offer much to even the brightest and most hard-working of its young people is one that is fundamentally sick.

In this context the fact that many of these youngsters are supporting Jeremy Corbyn is not at all surprising. What is surprising is that the political establishment are so narcissistically self-absorbed that they cannot see that his rise represents their own abject failure.

November 7, 2015

Blairism vs the left

The difference between Blairites and the left isn't merely one of policy prescriptions. It's also about the diagnosis of capitalism. John Rentoul's response to my post yesterday alerts me to this fact.

Here's what I mean. To a large extent, New Labour's thinking was founded in large part upon a belief in the dynamism of capitalism. It thought that capitalism would increase investment and productivity if only governments could provide (pdf) the right policy framework, such as the macroeconomic stability required to give firms the confidence to invest. It thought capitalism could create good jobs; Blair's talk of "education, education, education" arose from the idea that skill-biased technical change would increase the demand for skill labour. And it thought it could improve the efficiency of public services by importing management practices from the more dynamic private sector.

However, many of us now doubt this premise. Investment has declined as a share of GDP as firms prefer to build up cash. Productivity growth has slumped. And job polarization, the degradation of erstwhile "middle class jobs" and migration of workers to insecure and poorly-paid self-employment all suggest that capitalism is no longer providing satisfying work.

Quite why all this has happened is a separate story. But you don't need to be a Marxist to believe it: those economists who are most vocal in discussing secular stagnation are leftist social democrats rather than Marxists.

This raises the question: how can Blairites deny the facts which seem to me to speak of a loss of capitalist dynamism?

There are low-level quibbles one can have with the data; maybe some business investment is counted now as consumer spending, such as spending on laptops. Maybe innovations have raised consumer surplus rather than measured output; the fact that books, music and journalism are now available for free does nothing for GDP. But I doubt these explain away all of the facts suggestive of stagnation.

It's also possible that what we're seeing is just a temporary malaise. Maybe a revival of animal spirits will raise investment and productivity. However, the fact that the future is unknowable means we shouldn't put much weight upon this possibility.

There is, though, a more promising way of denying that capitalism has lost its oomph. It could be that all the symptoms of a loss of dynamism are in fact the result not of a secular crisis of capitalism but of weak aggregate demand. Such weakness has depressed productivity (via Verdoorn's law), interest rates, employment and capital spending. If we had more expansionary fiscal policy - not just in the UK but around the world - what looks like secular stagnation would disappear.

This, though, leads me to a paradox. If this is the case - and I don't know whether it is or not - then it is Blairites who should be most hostile to austerity. They should be complaining not only that austerity is destroying jobs but that it is also undermining faith in capitalism by leading folk like me to mistakenly attribute to capitalism what are in fact the results of bad policy. By contrast, we lefties should be slightly less hostile to austerity. Sure, we agree that it is bad for workers. But we suspect that even if we had sensible macroeconomic policy, many of capitalism's faults would remain.

But of course, this is exactly not what we're seeing. The million mask march was not dominated by Blairites. In fact, it is they who have actually been accommodating of austerity, even to the extent to failing to oppose Osborne's imbecilic fiscal charter.

What explains this paradox? The most obvious possibility lies in a difference of priorities. I want to try to understand the economy whereas Blairism is essentially about trying to win elections - and these are two different and perhaps even irreconcilable objectives.

* That spike in my second chart in 2005 was because of a reclassification of investment in the nuclear power industry, which uglifies the chart but doesn't change the story.

Chris Dillow's Blog

- Chris Dillow's profile

- 2 followers