Chris Dillow's Blog, page 93

October 9, 2015

On forecasting recession

Richard Murphy says there is a "near inevitability" of a recession sometime soon. I'm not sure it's wise to make such a prediction.

I wholly agree with him - and with the IMF - that there are reasons to be worried. In fact, I'd add a couple to Richard's menu:

- The US breakeven inflation rate, at 1.2pp, is close to a six-year low. It implies that markets expect the Fed to undershoot its inflation target - which means bond markets think monetary policy will be too tight.

- At low inflation, the yield curve might no longer be the great predictor of recessions it has been in the past. The fact that the yield curve is upward sloping is therefore not as good a comfort as it once was.

However, recessions are damned hard to foresee. Most professional forecasters - even before 2008 - have failed to see them coming. This might be because they are inherently unpredictable because they arise in part from failures of individual companies which might be magnified by network (pdf) effects. Because we don't know enough about these complex processes, time-dated forecasts are, as David says, "a mug's game."

Yes, a recession is possible. But there's a good reason to be wary of forecasting one now. Share prices tend to do much better from Halloween to May Day than in the other six months of the year. This suggests that people's assessments of economic prospects usually become too gloomy at this time of year. We should, therefore, be especially sceptical of pessimism now.

Of course, if he keeps forecasting a recession, Richard is certain to be right eventually. As Andy Haldane said last month:

Recessions occur roughly every 3 to 10 years. Over the course of a decade, they are overwhelmingly more likely than not.

But this is like a clock that's right twice a day: it isn't good enough for practical purposes.

My big problem with Richard's forecast, though, isn't that it might be wrong: it might not be. Instead, I've two other beefs.

One is that forecasting a recession gives the many non-economists who read Richard a false impression that economists can foresee the future. In fact, we can't. Knowledge of the future is a contradiction in terms.

Secondly, I'm not sure Richard has got the cost-benefit calculus right.

His main ideas - some of which such as opposition to austerity in its current form, a state investment bank and the possible need for alternative monetary policies are good - don't derive their strength from the claim that we're heading for recession. Merely warning of the possibility of recession is good enough. However, if we don't get a recession, his credibility will be called into question to discredit these ideas - whilst if we do get a recession his call will be forgotten or dismissed (rightly) as a lucky guess. He's therefore giving his opponents a stick to beat him with, and unnecessarily so.

October 8, 2015

Coping with unreplicability

"Economics research is usually not replicable" say (pdf) Andrew Chang and Phillip Li (via).

This problem is not confined to economics: it also seems to be the case in psychology (pdf) and medicine. Perhaps, therefore, the problem is a general (ish) academic one: pressure to publish and win research grants lead researchers to, ahem, tweak their findings.

Nevertheless, it poses a problem for those of us who are consumers of economic research: how should we respond to this?

First, we should remember Dave Giles' Ten Commandments, in particular:

Check whether your "statistically significant" results are also "numerically/economically significant"...

Keep in mind that published results will represent only a fraction of the results that the author obtained, but is not publishing.

Secondly, we should remember the Big Facts. For example, one the Big Facts in finance is that active equity fund managers rarely (pdf) beat the market (pdf) for very long, at least after fees. This, as much as Campbell Harvey's statistical work (pdf) reminds us to be wary of the hundreds of papers claiming to find factors that beat the market.

To take another example, Pritchett and Summers remind us of another Big Fact (pdf):

The single most robust empirical finding about economic growth is low persistence of growth rates...Episodes of super-rapid growth tend to be of short duration and end in decelerations back to the world average growth rate.

This warns us to be sceptical of findings that national policies, institutions or cultures have significant long-lasting effects on growth.

Thirdly, we should ask: is this paper consistent or not with other findings?

Take this paper which claims that fund managers perform badly after they have suffered a bereavement. This seems a mere curiosum. It's not. It's consistent with experimental evidence that sadness increases present bias, and with another Big Fact - that stock markets do better in winter, perhaps because longer nights in the autumn depress investors and share prices.

One of my favourite examples here is momentum. When I first saw Jegadeesh and Titman's claim that shares that have recently risen tend to carry on rising whilst fallers continue falling, I thought it was an interesting curiosity. But a similar thing has been found in currencies, commodities and even in sports betting. All this suggests that momentum is a reasonably robust fact.

But here we have an inconsistency: how do we reconcile this claim with the Big Fact that fund managers don't often beat stock markets?

This brings me to my fourth principle. We must ask: is there a sound theoretical reason for these findings, which reconcile them to the Big Facts?

Initially I thought momentum's out-performance was possible because fund managers were looking for accounting-based anomalies rather than behavioural ones. This, though, has become less plausible given the interest in behavioural finance since the 90s. But there is another possibility, pointed out by Victoria Dobrynskaya. It's that momentum stocks often have "bad beta"; they carry benchmark risk which makes them unattractive to fund managers with the result that they are under-priced to reflect such risk.

Now, here's the thing. It is, I suspect, rare for papers to satisfy these criteria. Of course, a lot of findings are worth thinking about. But few are actionable. And those that are are ones which fit other findings, Big Facts and theory.

My principles, I hope, are a form of informal Bayesianism. They are intended to steer the middle ground between a bigoted cleaving to our own prejudices on the one hand and gee-whizz gullibility on the other.

You might wonder why I've taken my examples from financial economics. It's partly because my ignorance of this field is less profound than others. But it's also to remind you of another Big Fact - that economic research is not, and should not be, about armchair windbaggery but rather about how to help people make better real world decisions.

October 7, 2015

"The country can't afford"

There's one thing George Osborne said in his Conference speech this week which looks odd. It's this:

We simply can���t subsidise incomes with ever-higher welfare and tax credit bills the country can���t afford.

However, recipients of tax credits are part of the country too. The IFS estimates that the 8.4 million of these will on average lose ��750 per year because of Osborne's cuts. For a lot of the country, it is not tax credits which are unaffordable, but the cuts in them.

What's going on here? Part of the answer is that Osborne is perpetuating an error which the Tories - and indeed journalists - have been committing for years: he is equating the government's finances with the nation's. Mr Cameron did just this when he justified the cuts to tax credits by speaking of a "need to get on top of our national finance."

Of course, any fool can see that this is wrong: the country and the government are not the same thing. For a large part of the country, tax credits improve their finances.

There's a related error - what I've called the cost bias. The cost of tax credits is NOT the ��29.5bn which the government spends on them. This is a transfer. Instead, the costs are the deadweight costs associated with them: for example, the cost of administering a complex system (which is one reason why I prefer a basic income), or the disincentive effects they create - for example, the higher taxes levied on other people to pay tax credits. The latter are, however, moot (pdf): a big purpose of tax credits is to raise in-work income and so incentivize work. Whether tax credits are therefore a cost at all is thus questionable*.

I fear, though, that what we're seeing here isn't just a neutral intellectual error. In defining the country and the nation to exclude the low paid, the Tories can create the illusion that the interests of the worst-off are not part of the national interest. This is an old trick of the ruling class. Here's C.B. Macpherson describing 17th century attitudes:

The Puritan doctrine of the poor, treating poverty as a mark of moral shortcoming, added moral obloquy to the political disregard in which the poor had always been held...Objects of solicitude or pity or scorn and sometimes of fear, the poor were not full members of a moral community...But while the poor were, in this view, less than full members, they were certainly subject to the jurisdictions of the political community. They were in but not of civil society. (The Political Theory of Possessive Individualism, p226-27)

Jeremy Hunt's claim that tax credit recipients lack self-respect and dignity echoes this.

In this way, Osborne's rhetoric serves to create an illusion that the interests of the poor are antagonistic to the "national interest". You didn't think Theresa May's concern about a "cohesive society" was sincere, did you?

* Not least because of the question: cost relative to what?

October 6, 2015

Demand deniers

The Tories seem to be demand deniers, in the sense that they seem oblivious to problems of weak demand. Three things make me say this.

First, Jeremy Hunt tries to justify cutting tax credits by claiming that he wants to create a culture of hard work.

Let's leave aside the fact that working long hours is often a sign a economic failure - of low productivity - and ask: what would happen if people offered to work longer?

The answer is that, in many cases their employers would reject their offers. There are already 1.28 million people who are working part-time because they cannot find full-time work. This tells us that, for very many people, the problem isn't a lack of culture of hard work but a lack of demand for their services.

Secondly, in speaking of immigration, Theresa May says:

We know that for people in low-paid jobs, wages are forced down even further while some people are forced out of work altogether...

At best the net economic and fiscal effect of high immigration is close to zero.

Let's leave aside the fact that we don't know this at all because it is wrong. Just think about elementary economics. An increased supply of labour could force its price down and if demand is price-inelastic employment won't increase much. But the solution to this is to increase aggregate demand so that wages and employment do increase. You don't need to believe me on this. Just look at what Ms May's own department says (pdf):

There is relatively little evidence that migration has caused statistically significant displacement of UK natives from the labour market in periods when the economy has been strong...

But during a recession, and when net migration volumes are high as in recent years, it appears that the labour market adjusts at a slower rate and some short-term impacts are observed.

It is not immigration that's the problem, therefore, but weak aggregate demand.The solution, therefore, is not immigration controls but better demand policies.

Thirdly, the Tories' proposed cuts in tax credits overlook one of the great trends in the economy over the last 40-odd years - that some mix of globalization and technical change has reduced demand for less-skilled labour with the result that millions of people have low pay. Proposed rises in the minimum wage will not solve this problem, not least because many of the low paid earn a little more than the minimum wage. Tax credits exist not because the Labour government was profligate, but because it recognised that topping up the incomes of the low-paid was a roughly least-bad solution to the problem of low demand for less skilled work.

These three examples raise the question: why are the Tories demand-deniers? Alex offers one answer: it's because they still believe that poverty is the fault of the individual - they are committing the fundamental attribution error.

The counterpart to this is a perhaps wilful failure to see that there are also systemic reasons for low pay - not just bad policy, but fundamental properties of the capitalist economy.

October 5, 2015

Trident, & the limits of rationality

Deliberation, which those who begin it by prudence, and continue it with subtilty, must, after long expence of thought, conclude by chance.

Looking at the debate about whether to renew Trident reminded me of these words of Samuel Johnson.

To see why, let's put aside the principled arguments on either side - about national prestige on the one hand or the immorality of threatening to kill millions of people - and consider the pragmatic case. This is that, without a nuclear deterrent we might be blackmailed or even attacked by someone with nuclear weapons, and that a deterrent would prevent this*. In this sense, buying Trident is like buying insurance - protection against a small but horrible risk?

But here's the problem: how great is this risk? Is it one in a 100? One in 1000? 10,000? We can't know, even to within an order of magnitude. This renders any cost-benefit case for Trident practically useless because its benefits are unknowable.

What we do know, though, is that people are terrible at judging probabilities. Of especial relevance here is our tendency to over-rate salient or easily imaginable risks and underweight less salient ones - and it is possible that countless TV shows and films about Dr Strangelove types have contributed to increasing the salience of nuclear threats and so to overestimating the need for Trident.

The objection that we must err on the side of prudence because we cannot take risks with Britons' lives cannot apply. There is an opportunity cost to Trident: the real resources spent on it could be spent on reducing risks to lives in other ways - better road safety, better medical care and research, anti-crime measures and so on. If we cannot quantify Trident's insurance value, we cannot know whether it is a better use of resources than these alternatives.

Herein lies a puzzle. Intuitively, I'd expect people who disagree about the case for Trident to differ in other ways. I'd expect advocates of Trident to be more risk- and ambiguity-averse than its opponents: if they are keener to buy nuclear insurance they should also be keener to buy other forms of insurance and be less inclined to gamble or invest in equities. Empirically, though, this seems doubtful. Whether this confirms that our judgments of probabilities are skew-whiff or whether our attitudes to risk differ from context to context is another matter.

It's in this sense that Dr Johnson was right. Given the impossibility of judging the probability of us really needing nuclear weapons, what looks like prudent deliberation about them is in fact based upon chance.

My point here, though, is not really about Trident. It's about the limitations of evidence-based policy and cost-benefit analysis - and in fact technocracy generally. In some cases, uncertainty is so great as to render these uninformative: I suspect that several military decisions fall into this category. What Nick calls the "tough decisions of Very Serious People" might in fact be much less well-founded than they pretend.

* I'm assuming here that the deterrent would work if needed - that the insurance policy would pay out. Sceptics doubt this, but it doesn't affect my point.

October 1, 2015

The trade slowdown

I have in the past complained about centrist utopianism. Tim Montgomerie in the Times offers an example of this. He points out "nothing has actually done more in world history to ensure the poor don't stay poor...than the advance of free trade" and then asks: "Do politicians such as Mr Corbyn really want to roll back globalization?"

This overlooks an important fact - that the pace of globalization has already slowed markedly not because of leftist politicians but because world capitalism is faltering.

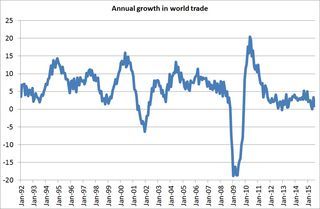

Figures from CPB show that the volume of world trade grew by only 0.8 per cent in the last 12 months.This isn't a sudden dip, but seems part of a post-crisis trend for slow growth. In the 15 years to December 2007, world trade grew by 7% per year. Since then it has grown only 2% per year.

This is why I accuse Tim of centrist utopianism; his claim that world trade will lift people out of poverty ignores the fact that this trade has slowed. To paraphrase Tom Paine, he is admiring the plumage but ignoring the sick bird.

There are many possible reasons why world trade has slowed. One possibility is that greater uncertainty about exchange rates or the availability of credit are discouraging firms from exporting. Some firms have become more aware of the impossibility of overseeing long supply chains and so are reshoring production. Perhaps the same depressed animal spirits that are suppressing capital spending are also suppressing investment in export sales' efforts. Or perhaps poorer nations such as China are victims of their own success: rising wages mean their cost advantage is diminishing and with it western firms' desire to source goods from them.

This might be important. We know that a country can reduce abject poverty by opening itself up to global trade and attracting investment to take advantage of its low wages. But this cannot go for long: there are many cases of countries falling into a "middle income trap" in which growth stagnates and with it the pace of poverty reduction. As Lant Pritchitt and Larry Summers wrote (pdf):

Regression to the mean is the single most robust finding of the growth literature, and the typical degrees of regression to the mean imply substantial slowdowns in China and India relative even to the currently more cautious and less bullish forecasts.

One reason why stock markets have reacted so badly to China's slowdown is that they fear this very possibility.

This, though, implies that formal globalization alone might not be sufficient to ensure a continued rapid pace of poverty reduction.

The issue, therefore, is not merely whether capitalism is desirable or not. It is also: how healthy is it? Partisan cheer-leading pieces such as Tim's overlook this crucial question.

September 30, 2015

On confined expertise

"Why is Richard Dawkins such a jerk? asks Matthew Francis.Some recent laboratory experiments help shed light upon this.

Researchers at Microsoft first looked at professional pundits' predictions for the NBA playoffs - which are best-of-seven matches - conditional upon seeing the results of previous games in the series. They found that the professionals' forecasts were more internally consistent than amateurs' forecasts, suggesting that the experts are more rational than the amateurs. However, when the pundits were then asked analogous questions about the probability of seeing red and black balls drawn from an urn, this superior internal consistency disappeared. They conclude:

Expertise fades in the lab even when the lab explicitly mimics the field.

This is consistent with some earlier research (pdf) by Steve Levitt and colleagues, who have found that professional poker players' ability to use minimax strategies deserts them when they are asked to play abstract games in the lab.

This corroborates the claim made by Dan Davies in a classic post: there is no such thing as a general purpose expert. As Richard Feynman said, "a scientist looking at nonscientific problems is just as dumb as the next guy.���

Instead, as George Loewenstein has said (pdf), "all forms of thinking and problem solving are context-dependent." When they are taken out of their context, experts lose their expertise.

Richard Dawkins is the poster-boy for this. He's a brilliant popular scientist, but can be a prat in other contexts. But of course he is not alone. Think of Niall Ferguson or James Watson or Tim Hunt or Steve Levitt, or many businessmen in politics. Peter Spence's advice seems, therefore, reasonable:

It'd be great if we all treated the opinions of Nobel prize winners outside of their field of expertise as basically irrelevant.

For me, there's something sad here. It seems that the scientific approach - such as the question "what counts as evidence here?" - is hard to apply outside of one's own field. In this sense, perhaps science and religion are closer than Professor Dawkins would like to think: just as many Christians forget their Christian principles when they are outside the church, so scientists forget their scientific principles when they are outside the lab.

September 29, 2015

Comfortable?

Janan Ganesh interprets the rise of Corbyn as a sign of Britain's prosperity - that people "can afford to treat politics as a source of gaiety and affirmation":

A Corbyn rally is not a band of desperate workers fighting to improve their circumstances, it is a communion of comfortable people working their way up Maslow���s hierarchy of needs.

I fear this misses two points.

One is that twas ever thus. Left-wing movements have always contained - and often been led by - the well-off. Lenin, Trotsky, Mao and Castro were all nice middle-class boys. Several of the leaders of the 1945-51 Labour government went to public school such as Attlee, Dalton and Cripps. And the soixante-huitards were the products of the long post-war boom. Left-wing politics has always contained a lot of Howard Kirk types.

One reason for this is that the moderately well-off feel a greater sense of grievance at inequality. It is people on ��40-50,000 a year who are excluded from the London housing market by gentrification. And, being sociologically indistinguishable from them, they are more apt to envy (perhaps wrongly) the 1%; it is the classmate who's done slightly better for himself that we envy more than the Queen.

By contrast, the really poor tend to be politically inactive. This might, as Janan says, be because they are lower down the hierarchy of needs and are too busy trying to make ends meet to attend rallies. But it might also be because they have adapted to their poverty and lack the sense of entitlement that motivates the better off to political activity (on either side).

Which brings to be another point that Janan omits. Not everyone is so comfortable. The IFS said recently:

The incomes of the non-pensioner population remain considerably behind where they were before the recession: in 2013-14 the median income of non-pensioners remained 2.7% below its level in 2007-08...

Rates of income poverty among working families have been rising.

You might object that such people are still well-off by most historic standards. But this omits the fact that, for many poor working families, incomes will fall a lot next year when tax credits are cut. And it also overlooks the fact that cruel and irrational benefit sanctions (pdf) and the bedroom tax are driving people to poverty, despair and even suicide: Kate Belgrave is essential reading on this.

In this sense, I fear that, like most political journalists in the Westminster Bubble, Janan is underplaying the fact that many people are not at all comfortable. This discomfort is both important and ameliorable. Yes, Janan is right to say that many Corbynistas are well-off middle-class types. But even so, there are real grievances and hardships out there. And Corbyn, despite his many faults, recognises this.

September 28, 2015

The benign deficit

There's a point I made in my previous post that I'd like to emphasise. It's that voters support austerity for the same, sometimes mistaken, reason that they support price controls - because they under-estimate the extent to which emergent processes sometimes produce benign outcomes.

What I mean is that what free marketeers say about the price system - that it is the benign outcome of uncoordinated individual decisions - is also true of government borrowing now.

This borrowing is the counterpart and effect of decisions by millions of companies and households (pdf) around the world to save and not invest*. Given that much of the rest of the world wants to be net savers, somebody must be a net borrower - and that somebody includes the UK government.

This borrowing is as John says a solution not a problem - because it is helping to sustain demand.

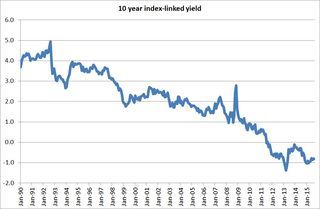

At this point I could write thousands of words about MMT. But why bother? Just look at real bond yields. These tell us that financial markets are untroubled by government borrowing - because the same net savings which cause this borrowing also cause low interest rates.

In this sense, the division of opinion is not between left and right but between economists and non-economists. Most economists are more or less relaxed about the deficit for the same reason that they often support freeish markets - because they appreciate that individuals' uncoordinated decisions sometimes have tolerable outcomes. Non-economists, being less aware of this, are keener for the government to "control its borrowing" just as they want state control over other aspects of the economy.

All that said, there are two massive caveats here.

First, I am NOT saying that deficits are always benign any more than I am saying that other emergent processes are. Whether either is the case or not varies from time to time depending upon the circumstances**. I can imagine - and have seen - circumstances where big government borrowing is a problem. It's just that those circumstances are not here not now.

Secondly, some of the reasons for high net private savings around the world are assuredly not benign: weak welfare states, a lack of consumer confidence and secular stagnation. In a better world, the government would be borrowing less. But inferring from this that the government should cut borrowing is like withdrawing medicine from a sick man because he wouldn't need it if he were healthy.

Which brings me to a problem. It's possible that many of the causes of global net savings - and we can to them ageing populations in Europe - are longlasting. To the extent that they are, government borrowing might persist. If so, the Fiscal Charter's promise to achieve a surplus on PSNB by 2019-20 might require yet more counter-productive fiscal tightening. Deficit reduction should be state-dependent, not time-dependent.

I appreciate that there political reasons why Labour might support the Fiscal Charter, but I'm not so sure there are good economic ones.

* I stress around the world: the counterpart to government borrowing is now an overseas deficit - which is to say net savings by the rest of the world.

** Note here that, yet again, the bigotry of anti-Marxists is 100% wrong. It is me the Marxist who is stressing that context is everything whilst anti-Marxists of right and left want to see lawlike generalizations where none are appropriate.

September 24, 2015

Paradoxes of control

"Why do the British dislike the free market?" asks John Rentoul, pointing to public support for nationalization and opposition (pdf) to privatization: he might have added support for rent and price (pdf) controls too.

For me, this raises three paradoxes.

Paradox one is that, as John says, "left-wing" policies are popular but left-wing parties are not.

One reason for this, at least in May's general election, is that as Jon Cruddas has said the voters disliked Labour's opposition to austerity.

There is, though, no contradiction between voters being "left-wing" on nationalization and price controls but "right-wing" on austerity.

The key word here is "control". People support nationalization and price controls for the same reason they support immigration controls; they want to feel that the government is in control. They under-estimate the extent to which spontaneous order or emergent processes produce benign outcomes without state direction*. The invisible hand is well-named: people can't see it.

I suspect that support for austerity arises from this same urge for control. People want to believe that the government is in control of its finances. They don't like the idea that government borrowing is the uncontrolled (and often benign) outcome of private sector choices to save or borrow.

Which brings me to a second paradox. Although voters want the government to expand its sphere of control, they don't want to expand their own control. There is pitifully little demand at the political level for greater worker control of firms.

I say this is a paradox because of a simple principle: control should be exercised by those who know the most and who have the most skin in the game. Many workers - those with job-specific human capital - have a lot to lose if their firm is badly managed and have the dispersed fragmentary knowledge to improve management. But the same isn't true for politicians: for example, George Osborne doesn't know better than the market or Low Pay Commission what is the right level for the minimum wage, and it's no great loss to him if he gets it wrong. We'd therefore expect to see more political demand for worker control than state control. But we don't. Which brings me to...

Paradox three. Although there's no political demand for worker control, many people vote for it with their own feet. Since current records began in 1984 the numbers of self-employed have risen by 67.5% to over 4.5m - an increase from 11.1% to 14.5% of all those in work.

Rick is of course right to point out that many of these are making little money in inefficient and doomed businesses, and many have been compelled into self-employment by a lack of decent alternative. But I suspect that people are also choosing self-employment even if it is insecure and badly paid because they want more control over their lives - or at least the feeling of control - than they can get from hierarchical employment. Research by Bruno Frey and colleagues has found that the self-employed are "substantially more satisfied with their work than employed persons" in many countries because they value autonomy in itself.

All this has an important implication. The phrases "left" and "right" are horribly misleading. The issue is: are uncontrolled emergent processes benevolent or not? Very many voters think not - which explains the otherwise paradoxical fact that they support "left-wing" price controls and "right-wing" austerity.

This in turn poses big political questions: how can we ensure that emergent processes are only reined in when they are harmful? Can we persuade voters of the virtues of spontaneous order without sounding like capitalist shills? Are there efficient means of satisfying the demand for control? These questions, rather than waffle about left and right, deserve more attention.

* Granted, capitalism's apologists sometimes overstate this point.

Chris Dillow's Blog

- Chris Dillow's profile

- 2 followers