Chris Dillow's Blog, page 96

August 6, 2015

Blairite optimism

Paradoxical as it might sound, Jeremy Corbyn is in one sense the Blairite candidate for the Labour leadership.

What I mean is that Corbyn is offering what Blair offered in the 90s - newness, change and hope. As Simon Kuper says in a different context, positivity and optimism sell. "Yes we can" won Barack Obama an election from nowhere. But few people vote for cowards, Quislings and nay-sayers.

In this sense, those who claim to be Blairites now are in fact the anti-Blairites. As Owen says, they're offering only negativity and sneers. And whereas Blair was a modernizer, today's Blairites seem to be the exact opposite; they refuse to see that the economy has changed since the 90s, and that this requires new politics.

This poses the question. What would a modern, optimistic Blairism look like? Here are some ideas:

1. "Britain can do better". UK productivity is 22% below that of France. This matters simply because low productivity means low wages. Policies to raise productivity are thus essential. Blairites should therefore be able to distinguish themselves from the Tories - who seem to think wages can be raised by legislative fiat - and from the Corbynites whose emphasis on anti-austerity under-estimates the UK's supply-side problems.

2. "Putting you in control". We've learned since the 90s that top-down management has its limits. This suggests a case for increasing the power of workers generally and consumers of public services. In fairness, Liz Kendall has seen this:

we need to go back to our roots as a party and ensure people have the power to shape their lives, the services they use, and the communities in which they live...We must ensure power lies with people in their workplaces, public services, schools and streets, not just the town hall.

The challenge is to ensure real empowerment, not mere tokenism.

3. "Strong enough to care." In its healthy phase, Blairism was open to globalization and immigration. This should be revived. Blairites should oppose the dehumanization of migrants, and point out that Britain isn't so desperate that it needs to deprive asylum-seekers of ��37 per week. We're better than that.

4. "Investing in the future." As Simon points out, a policy of targetting a zero current balance would allow Blairites to pander to deficit fetishism whilst at the same time promising to invest in infrastructure. They could easily argue, against Corbyn, that QE is unnecessary to this; with real yields still negative, bond markets are happy to finance investment.

5. "Making work pay." Taxes should be shifted from incomes onto land and inheritances.

There is, therefore, some kind of positive Blairite agenda. And yet, apart from Kendall's talk of empowerment and Burnham's of a national care service, we aren't hearing much of it. Why not?

One possibility is that such an agenda would fail. Maybe "moderate" policies just cannot shift economic growth by much, or perhaps secular stagnation is so entrenched that only a Corbynite socialization of investment can combat it. This, though, doesn't explain why the Blairites seem to have given up so easily. Perhaps they have become too stupefied by Westminster Bubblethink.

August 5, 2015

The sad death of free market pessimism

The hostile response to Paul Mason's Postcapitalism raises a question: why are rightists economic optimists?

I ask because that reaction seems to me to be part of a pattern. It tends to be free market types who are most critical of Malthusian-type pessimism, and I get the impression that it is left-liberal economists who are more worried by secular stagnation whilst rightists are more sanguine about it.

There is, though, no necessary logical connection between optimism and pro-capitalism. Joseph Schumpeter was an admirer of capitalism but feared it could not last. David Ricardo advocated free markets but feared that diminishing returns would choke off growth. And there was for a long time a melancholy tendency within conservatism - expressed most eloquently (pdf) perhaps by Michael Oakeshott.

It would be perfectly coherent to be believe that freeish market capitalism is a good thing but that it is imperiled not just by bad policy but by intrinsic developments such as diminishing returns or a loss of entrepreneurship. And yet free market pessimism is a view that seems to have faded.

Why?

Here - in no order - are some theories:

1. My premise is wrong. The fact that index-linked gilt yields are negative suggests that gilt investors, many of whom have pro-market views, are pessimistic about future GDP growth.

This, though, deepens the puzzle of why such a view isn't expressed much in the right-wing media.

2. Optimism is justified. Capitalism has survived many dangers, and has lifted millions out of poverty.

The problem with this is that, as Bertrand Russell famously said, the fact that something has happened in the past does not ensure its continuance. Paradoxically, the optimists might be making the same error as Malthus. Just as he looked at centuries of human history and inferred that mankind was doomed to subsistence, so free market optimists might be over-inferring from two centuries of success. It's quite possible that, at some time, the race between diminishing returns and technical progress will be won by the former.

3. The collapse of communism has led to triumphalism on the right.

The problem here is that centrally planned economies are not the only alternative to capitalism - though many on both left and right fail to see this.

4. Wishful thinking. Just as lefties want to believe that capitalism is doomed because it is bad, so the right wants to believe the opposite.

5.Class. Henrik Cronqvist and colleagues have shown that investors from wealthy families tend to own more growth stocks than those from poor ones, even controlling for their own wealth. This suggests that family backgrounds can predispose people to optimism. For example, Matt Ridley, author of the Rational Optimist, went to Eton - as did one of Mason's critics Douglas Murray. Of course, it's not true that all rightist optimists are posh and pessimists not so, but there might be a tendency here. I conform to it, being very risk-averse and from a poor home.

Points 4 and 5 suggest that what's going on here might not be based wholly upon a rational assessment of the facts. This is, of course, true of both right and left.

For that reason, I don't say this to attack rightist optimism. Instead, I do so to lament the disappearance of an important perspective - that of free market pessimism.

August 4, 2015

Back to pre-capitalism?

Paul Mason's claim that we're entering the post-capitalist era has met some some sneering from the right. But I wonder: might we not be reverting to a pre-capitalist era instead?

I mean this in three different senses.

First, we might be seeing a tendency for people to have multiple jobs. One feature of the sharing economy is that companies such as Airbnb and Uber allow people to be hoteliers and cabbies alongside their day jobs. There are increasing numbers of self-employed - many of whom are jacks of all trades - and, to a lesser extent, increased number of people with second jobs in the formal economy.

This represents a reversion to pre-capitalism*. E.P Thompson has described (pdf) how, before the arrival of large-scale manufacturing, workers performed a "multiplicity of subsidiary tasks". And Banerjee and Duflo show how many of the poorest (pdf) people in the world - those whom advanced capitalism hasn't sufficiently reached - have several small jobs.

Secondly, we are seeing a backlash against capitalism's tendency to undermine communities. Marx wrote:

Constant revolutionising of production, uninterrupted disturbance of all social conditions, everlasting uncertainty and agitation distinguish the bourgeois epoch from all earlier ones.

But as Karl Polanyi recognised (pdf), there will inevitably be a backlash against this. Which is what we're seeing. In its benign form, this takes the form of a preference for locally-produced food and even local currencies. In its nastier form, it consists of a hatred of immigrants. You can see all these as recrudescences of feudalism - a cleaving to community and (in the case of anti-immigrationism) belief that one's fate should be tied to where one was born.

Thirdly, secular stagnation, in its extreme form, might itself be a reversion to pre-capitalistic growth rates. In this context, Schumpeter is relevant. He described (chs XII-XIV of this pdf) how the revolutionary function of the entrepreneur was eventually subsumed into bureaucratic organization. One reason for stagnation might be that this has happened; the (over-)optimistic entrepreneur has been replaced by bureaucracy.

You might find it odd that I call this a reversion to pre-capitalism. But in a way, it is: hierarchy is pre-capitalistic - and, like feudalism, is sustained by irrationality and illusion.

Now, you might think I'm being mischievous here. I'm not sure. For one thing, Marx, Polanyi and Schumpeter all agreed that free market capitalism would undermine itself. Maybe this is what we're seeing.

And for another, there's a long and growing literature which shows how very distant history shapes our behaviour today - which suggests that attitudes formed before capitalism might still linger. As Michal Kalecki said of Poland in the 1960s: "Yes, we have successfully abolished capitalism; all we have to do now is to abolish feudalism."

* Or does it. Marx wrote:

In communist society, where nobody has one exclusive sphere of activity but each can become accomplished in any branch he wishes, society regulates the general production and thus makes it possible for me to do one thing today and another tomorrow, to hunt in the morning, fish in the afternoon, rear cattle in the evening, criticise after dinner, just as I have a mind, without ever becoming hunter, fisherman, herdsman or critic.

Note, however, that these are pre-capitalistic occupations. And there's a big difference between people doing many jobs because they are free to choose - as in Marx's description of communism - and because they must do so to make ends meet.

August 3, 2015

Is Corbynomics inflationary?

It's widely agreed that Jeremy Corbyn's popularity is due in large part to the mediocrity of the alternatives. As if to demonstrate this, Chris Leslie - Shadow Chancellor - claims that Corbynomics would be inflationary.

This isn't wholly unreasonable. A money-financed fiscal expansion - which is all "people's QE" is - would increase employment and aggregate demand. Conventional economics says this would reduce the "output gap" which would tend to add to inflation.

The claim might be reasonable. But we cannot make it with much confidence, for three reasons.

First, measures of the output gap are subject to considerable uncertainty (pdf) - so much so that Paul Ormerod and Chris Giles (who I guess are hardly Corbynites) think the concept is nonsense.

Secondly, the UK is an open economy and as the standard textbook says:

In an open economy, there is a range of unemployment rates consistent with the absence of inflationary pressure (Carlin and Soskice, Macroeconomics, p343)

It's possible, as Richard says, that disinflationary pressures in the euro are would hold down UK inflation.

Thirdly, Corbynomics isn't just about QE. It also comprises a deflationary policy - higher taxes on companies and the rich. These would tend to depress demand and employment and hence inflation. Whether there is net inflation depends upon the balance of the two. It's uncertain.

But so what if inflation does rise? As Tony Yates has said - and he's no loony lefty either - there might well be a case for a higher inflation target. I'm not sure he's right - but I'm pretty sure that 4% inflation wouldn't see the world cave in.

Maybe Leslie's right, then. Or maybe not. My Hayekian scepticism about the possibility of centralized knowledge of the complex process that is the macroeconomy prevents me being confident either way.

And yet I am depressed by his intervention,

The fact is that there are 5.4 million people who are unemployed or under-employed: 1.8m officially unemployed; 2.3m who are "inactive"but want to work; and 1.3m part-time workers who want full-time work. If inflation can rise when there's so much unemployment then we suffer from a massive supply-side problem. If this is the case, then Labour should offer some solution to this.

Which is just what Leslie is not doing. Instead, all he is doing is peddling fear. But given the choice between hope - however forlorn - and fear, Labour members can be forgiven for choosing hope.

July 31, 2015

Creating markets

Simon Jenkins' and James Kirkup's proposals to privatize lions to protect them has been derided by some as "peak Telegraph" and knowing the price of everything and the value of nothing. This, I fear, highlights the poverty of debate about the use of markets generally.

Simon's and James' thinking derives from the conventional economics of the tragedy of the commons. This says that if wildlife is unowned, nobody has a material incentive to conserve it and there will therefore be a tendency to over-hunt it. If, however, lions could be owned and hunting permits sold, the owner would have an incentive to protect lions from poachers. Privatization is, therefore a possible solution to the tragedy of the commons - though as Elinor Ostrom (pdf) showed, only one possibility.

There are, however, problems here. Not least is: can such private property rights be created and enforced?

One danger here is a re-emergence of the natural resource curse: if governments grant a valuable property right, people will fight over it, possibly impoverishing the country.

Another issue is whether such rights can be enforced. As Terry Anderson has shown (pdf), the emergence of property rights requires among other things that technology permits a lowish-cost enforcement of those rights. But in the case of migratory (pdf) species, this might be absent. There's also a principal-agent problem. Landowners might not be able to prevent poachers bribing rangers to let them kill the animals or to tempt them off the protected land: it's alleged that this happened to Cecil.

My point here is a simple one. Whether effective markets and private ownership can be created depends upon particular institutional and technical conditions.

This is, of course, a variant on Coase's famous point (pdf) - that there are costs to market transacting. These costs must be weighed against the costs of other forms of economic organisation - be it the firm or state control.

This applies to issues much nearer home. Whether public sector services should be privatized depends upon precise institutional detail: is it possible to write contracts which ensure a high quality of service without excessive rent-seeking? In Coasean terms, is the cost of market transacting lower than the cost of in-house production?

The answer will vary from service to service and place to place.

And herein lies my beef. In the case of lions and the NHS, this point is overlooked in favour of ideological soundbites: "Markets - yay!" "Neoliberalism - boo!" In fact, the issue is more technocratic than that. It all depends upon subtle details.

July 30, 2015

On Corbynomics

Jeremy Corbyn's economic policy deserves more attention than it's getting.

It seems to me that this comprises two necessarily related elements. One is higher corporate taxes: he wants to "strip out some of the huge tax reliefs and subsidies on offer to the corporate sector" - which he claims to be ��93bn a year. This would depress investment, by depriving firms of some of the means and motive to invest. However, this would be offset by "people's quantitative easing" - a money-financed fiscal expansion:

The Bank of England must be given a new mandate to upgrade our economy to invest in new large scale housing, energy, transport and digital projects.

This amounts to what Keynes called a "socialisation of investment":

It seems unlikely that the influence of banking policy on the rate of interest will be sufficient by itself to determine an optimum rate of investment. I conceive, therefore, that a somewhat comprehensive socialisation of investment will prove the only means of securing an approximation to full employment; though this need not exclude all manner of compromises and of devices by which public authority will co-operate with private initiative. (General Theory, ch 24)

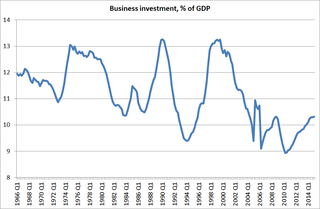

This is a response to a genuine problem - low capital spending. The share of business investment in GDP has (in nominal terms) been trending downwards since the mid-70s.

Quite why this has happened is unclear: I suspect it owes more to fundamental problems of a lack of monetizable investment opportunities than to short-termism, but this doesn't much matter for current purposes. Corbyn's view seems to be that, if private enterprise won't invest, the public sector should.

I don't have much problem with the diagnosis here. But I do with the remedy, for three reasons.

First, how exactly will the public sector investment projects be chosen? One reason why the Bank of England didn't conduct QE through the corporate bond or equity markets was that it didn't think it had the expertise to pick companies. So how can it appraise energy and digital projects?

One answer to this is to have a National Investment Bank. But again, where will its expertise be drawn from? I fear this is a form of managerialism - a faith in central managers.

The second question is: who will do the actual investing? There's a case for the state to invest in infrastructure. But we also need corporate investment, to raise private sector productivity.

It's possible that the higher aggregate demand created by people's QE will stimulate private sector investment via accelerator mechanisms. Maybe high expected demand will overcome higher corporate taxes. Or maybe not.

My third problem is raised by David Boyle: where are the mutuals? Corbyn's world seems to comprise just two actors: the state and capitalist corporations. There seems insufficient emphasis upon decentralized forms of economic control, be they Robin Hahnel's participatory planning, Roemerian market socialism or workers' control.

Granted, Corbynomics might be a building block towards these. But as it stands, it looks to me like replacing one set of bosses with another - which isn't as egalitarian as it could be.

Nevertheless, Corbyn is at least asking the right question - how to stimulate investment - which is, sadly, more than his rivals are doing.

July 28, 2015

On centrist utopianism

Here are some things we've seen recently:

- Andy Haldane says shareholder capitalism is too short-termist, without asking whether it is possible to change this, or whether short-termism might in fact be a rational response to massive uncertainty about technical change and creative destruction.

- There's a warning that the rising minimum wage might cause a "catastrophic failure" in home care. Apparently, higher wages have a cost: who'd have guessed?

- Alan Milburn seems scandalized by the fact social mobility is blocked by parents' urge to help their kids.

There's a common theme here. It's centrist utopianism - the idea that moderate and feasible tweaks within capitalism can generate big improvements. Haldane seems to think we could see much higher investment if only capitalism could be reformed*; minimum wage advocates might be underplaying the costs of the policy; and supporters of social mobility fail to appreciate that human nature is itself a massive obstacle to greater equality of opportunity.

Here are some other examples of centrist utopianism:

- The idea that macroeconomic policy can stabilize economies. This runs into the problem that recessions are inherently unpredictable and so policy cannot be changed in advance of downturns; the Bank of England didn't begin QE until 12 months into the recession. It also assumes that governments would want to stabilize the economy if only they could. But as Kalecki famously pointed out, this is dubious.

- The idea that structural reforms can quickly and significantly increase growth. This is in fact pretty much impossible.

- The pretty much unquestioned faith in managerialism and command and control techniques; the response to pretty much any organizational failure is a demand for "better leadership". This ignores the possibilities that "leaders" lack the knowledge and rationality to control complex organizations, or that such leadership has costs in terms of facilitating rent-seeking and demotivating employees. This ideology isn't confined to organizations. For a long time, there's been a divide in Labour between those who think change can be achieved merely by winning elections, and others who think there must be broader social and cultural change.

- The notion that public sector bodies, including the BBC, can increase efficiency by shedding waste. This fails to appreciate a basic lesson of public choice - that bureaucrats look after themselves, and so wasteful layers of management can become entrenched.

I say all this as a counterweight to a longstanding prejudice - that centrists and moderates are realistic and hard-headed whilst we leftists are utopian dreamers. Of course, this accusation applies to some on the left - anything is true of someone - but for me the opposite is the case. I'm a Marxist because I'm a pessimist. It is those who think that (actually-existing) capitalism is easily reformable so that inefficiencies and injustices can be eliminated who seem to me to be the dreamers.

* I might be doing him a dis-service. Maybe he believes that low investment is an ineradicable feature of capitalism.

Another thing. You might object that capitalism has seen huge improvements in workers' well-being. However, just because something has occurred in the past doesn't mean it will continue to occur. Maybe reformers have picked the low-hanging fruits. And if we are in secular stagnation, then the economy becomes a zero-sum game - which reinforces my pessimism.

July 27, 2015

"Demography is destiny"

Talking about the "glass floor" which limits social mobility, Alan Milburn says:

It���s a social scandal that all too often demography is still destiny.

This is true in a far bigger way than Mr Milburn means. There's a policy which suppresses social mobility and ensures that demography is destiny for millions of people.

I refer, of course, to immigration controls.

If you support social mobility you must, logically, favour open borders. For example, someone migrating from Zimbabwe, where GDP per head is barely $2000 per year, to a minimum wage job in the UK would see their income rise tenfold. That's massive upward mobility. And yet far from wanting to encourage such mobility, most people in the UK want to suppress it: a letter in the Telegraph today calls for water cannon to be used against migrants.

However, a world without immigration is one in which demography is destiny. People born in the UK will be at least ten times as rich as those born in Zimbabwe, regardless of merit or ability. This is a form of feudalism. Just as feudalists thought that people's fate should be determined by the station they were born into, so anti-immigrationists think our fate must be tied to the country we were born into.

This seems odd. If it's a "scandal" that demography is destiny then immigration controls must be scandalous. So why don't people believe they are?

I don't think the answer lies in conscious racism - that we want upward mobility for Brits but not Zimbabweans: I doubt that three-quarters of the British people are that racist.

One possibility is that one might favour open borders in principle but believe that they are simply impractical - especially for a single small country to adopt on its own. This, I think, is a reasonable position. But I'm not sure how widespread it is. I've not heard a politician say "I support open borders in principle; the problems are merely practical."

Another possibility is that some advocates of social mobility desire it not as a way of improving individuals' life-chances but as a way of justifying inequality; if everyone has a chance of success, then, it is thought*, inequalities are legitimate - as long as you don't think about poorer countries.

I suspect, though, that in most cases something else is going on. People just don't think what social mobility really means. Just as they don't appreciate that equality of opportunity requires a massive limitation of freedom - for example, banning private tuition - so they just don't see that social mobility must mean free migration. They are like those 18th century people who thought they were devout Christians but who kept slaves. It's easy to sustain two contradictory positions simply by not thinking.

* Very dubiously - but leave that aside.

July 25, 2015

On welfare incentives

A loyal reader has chastised my defence of welfare benefits for ignoring incentive effects. This deserves a reply.

The issue here is not about Osborne's welfare cuts, simply because these haven't, net, made much difference to incentives. On the one hand, the rise in the "living wage" relative to Universal Credit will increase incentives to work. But on the other hand, this won't affect under-25s (who aren't covered by the wage floor); cuts to in-work tax credits reduce work incentives; and the higher taper rate reduces incentives to work longer. Overall, says the Resolution Foundation's David Finch:

These changes will do very little to improve the incentives for low paid families to find a path into work and then to progress.

Instead, the issue is a fundamental trade-off facing any benefit system - that of incentives versus risk reduction. Low out-of-work benefits sharpen incentives for the unemployed to find work. But they also mean that people losing their jobs face a bigger cut in income, which could deepen any recession.

I'll concede that the incentives argument has some merit. Some of the unemployed do reject job offers because they'd prefer to stay on benefits. And Barbara Petrongolo has shown that a tougher benefits regime does incentivize job-finding. The question is: how strong is this argument?

Let's do a back-of-the envelope estimate. If we could move 300,000 people - almost all those who have been unemployed for more than two years - from unemployment to full-time minimum wage work GDP would rise by around ��5bn: this is ��3.8bn of wages plus around ��1.2bn of extra profits from employing them. This is around 0.3% of GDP. However, a serious recession could easily cost 5% of GDP. A generous welfare state, being a strong automatic stabilizer, would save a big fraction of this.

Which should we prefer? It depends on many issues:

1. How sensitive is job-finding to unemployment benefits? I doubt if many people think: "my benefits have been cut, so I might as well stop watching Jeremy Kyle and take up that offer of a professor of maths." I suspect many of the voluntarily unemployed are borderline unemployable and so not very amenable to incentives. This is consistent with evidence that the 2010-15 welfare reforms, such as the benefit cap, did not greatly increase job-finding.

2. What's the mechanism whereby the demand for labour increases to meet the increased supply? One possibility is that wages get bid down. But this channel is silted up by a rising minimum wage. Another possibility is that vacancies get filled faster, which makes firms more efficient. But Ms Petrongolo shows that those who are incentivized to find work by benefit cuts are less likely to stay in work - which suggests that low benefits lead to worse job matches, which is bad for firms.

3. Can macro policy be used to stablize the economy? If the answer's yes, then there's less need for a generous welfare state as a stabilizing device. My view, though, is that recessions are unpredictable and so policy cannot prevent them.

4. Do recessions have permanent effects on GDP? In my example, the benefits of getting the unemployed into work - subject to the above caveats - are long-lasting, whereas the benefits of stabilizing recessions come only once every few years. However, if recessions have long-lasting adverse effects upon future growth, then it becomes more important to cushion ourselves from them.

5. How important is it to punish those who violate the norm of reciprocity? The issue here is not merely one of economics, but ethics. Many people hate the idea that some of the unemployed are getting something for nothing at the expense of the rest of us. How much weight does this preference have?

6. How should we weigh false positives against false negatives? A tough welfare regime punishes "scroungers", but also the "deserving poor" - those unlucky to lose their jobs, whilst a more generous welfare state is kinder to both.

Many people's attitudes to these issues are based in part upon ignorance - an overestimation of benefit spending. Nevertheless, in the fact-based world, reasonable people will disagree here. But let's be clear: I am not ignoring incentives, but merely doubting how much weight we should put upon them.

July 24, 2015

Yes, Labour must change

Tony Blair's speech this week, paradoxically, reminded us of the need for new, radical economic policies. He said:

The most important characteristic of this world is: the scope, scale and speed of change. Change defines it.

Let's leave aside the obvious snark that one thing that hasn't changed is Blair's talk of change. He was talking about the "breathtaking pace of change" 20 years ago*. As Alan Finlayson wrote (pdf), the rhetoric of modernization has been a key element of Blairism.

Instead, my point is that it is because the world has changed that New Labour is no longer relevant. For example:

- New Labour worried that the "bond market vigilantes" constrained fiscal policy. That was a reasonable concern when real interest rates were four per cent. But now they are negative a loose fiscal policy is more feasible.

- New Labour thought that if governments could provide the right conditions - such as macroeconomic stability - then businesses would invest. But (nominal) investment-GDP ratios have fallen since then. This suggests governments need some other policies to raise investment - perhaps more more interventionist ones.

- In the 90s, labour productivity was growing nicely. Now it's not. Productivity policy is thus more important.

- The sort of inequality that troubled New Labour was the gap between the moderately well-off and the poor; it thought increased education was one way of tackling this. This gap, however, has declined recently. Instead, the most salient inequality is now the income share of the top 1%. This requires different policies.

- The productivity slowdown might be evidence that managerialism and the target culture have limits. Perhaps a better way to raise productivity is to increase worker control.

- The Great Recession has reminded us that recessions are unpredictable. This means that macro policy cannot adequately stabilize the economy and that we need instead a generous welfare state as an automatic stabilizer. As Blair says, it is a means to protect those "disadvantaged by the changes whirling round them."

However, party politics has changed as well as the economy. The left-centre-right dichotomy might no longer be so important. Ukippers, for example, want immigration controls but also nationalization and price controls: are they rightists or leftists, or do the old labels no longer apply? And the wipe-out of Lib Dems and rise of Ukip and SNP might suggest that those who claim to be centrists fare badly against those who attack, or pretend to attack, the centre.

Now, I'll concede that Blair might have a point when he says that some forms of radical leftism can be reactionary. Sometimes, I fear that some leftists' demands for high corporate taxes and nationalization are a relic of the 1970s beliefs that capital is immobile and top-down hierarchy desirable and feasible.

There is, though, another form of leftist policy - one that recognizes the need for a generous welfare state, worker empowerment and well-functioning markets. This requires that Labour abandons not just relics of the 1970s, but relics of the 1990s too.

* New Britain: My vision of a young country, p203

Chris Dillow's Blog

- Chris Dillow's profile

- 2 followers