Chris Dillow's Blog, page 98

July 4, 2015

The something for nothing culture

One thing I'd like George Osborne to do in Wednesday's "emergency" Budget is to end the something for nothing culture.

I know someone who has made almost ��400,000 tax-free without working - equivalent to almost 20 years of getting the maximum welfare benefits the Tories are considering. Thanks to this, he is looking forward to a prosperous early retirement. This is surely unfair, given that so many younger people might have to work until they drop.

That someone, of course, is me. And the ��400,000 is the tax-free profit I made from rising house prices.

In this respect, I am typically British. Just look at the TV schedules. Antiques Roadshow, Homes under the Hammer, Cash in the Attic and anything starring Phil & Kirsty or Sarah Beeny testify to our desire to get money without working. The idea that something for nothing culture is confined to benefit recipients is utterly wrong.

It is, however, economically damaging in at least four ways:

- It diverts finance away from productive uses. For every pound UK banks lend to manufacturers, they lend almost ��36 to home-buyers: ��35.3bn vs ��1264.8bn (pdf). It might also contribute to financial crises as bank periodically learn that mortgage lending isn't as safe as they think.

- As Andrew Oswald and Danny Blanchflower have shown (pdf), it contributes to unemployment, in part because the deadweight costs to home-owners of moving house slow down the extent to which people can move to where there are jobs.

- It creates a large constituency with a vested interest in loose monetary policy and higher inflation; inflation favours home-owners but hurts renters. The cost here isn't, perhaps (pdf) merely the werlfare costs of high inflation but the malinvestments, bubbles and increased risk of financial crises that result from low rates.

- If people are looking to get rich merely from rising house prices, they'll be diverted from productive activity. Granted, my early retirement won't be a devastating loss to anyone, but across millions of people such early retirement - and the diminished need to make full use of their human capital event whilst they are working - might well represent a big loss.

These mechanisms are consistent with a big fact - that across countries, high home ownership is associated with poor macroeconomic performance; Greeks and Italians are far more likely to own houses than Swiss or Germans*.

Which brings me to the Budget. In proposing to cut inheritance tax on housing George Osborne will exacerbate all these problems by further increasing the constituency with an interest in house price inflation and in getting something for nothing. This is not just inegalitarian - most of those who stand to inherit a ��1m house are rich already - but also, I'd suggest, inefficient not just for the above reasons but also because lower tax on inheritances mean higher taxes elsewhere.

What it is not, though, is unpopular. Which reminds us that a big obstacle to a more just and efficient economy is public opinion.

* Of course, the causality doesn't just run from home ownership to shonky economies, but this is suggestive of some link.

July 2, 2015

Poverty & ideology

Iain Duncan Smith wants to shift the definition of child poverty from one based upon low incomes to one based on educational attainment, worklessness and addiction.

What's at stake here is, as Amelia Gentleman points out, an ideological issue: is poverty due to individual failings or to the structure of society?

Of course, some parents of poor children are feckless workshy druggies. But in a population of 64.6 million people, pretty much anything is true of someone.

Two big facts, however, suggest that the link between child poverty and parental failure is weak. One comes from the DWP's own report:

Children in families where at least one adult was in work made up around 64 per cent of all children in low income [before housing costs] in 2013/14 (p46 of this pdf).

Think what it means to be in work. It means you've impressed an employer sufficiently to get hired, and you are managing to turn up roughly on time most days. You have, in short, got your shit together. And yet you're still unable to get your family out of relative poverty.

Secondly, Andrew Dickerson and Gurleen Popli point out that there is zero correlation between material child poverty and a measure of parental involvement based upon facts such as whether parents read to their children or given them regular meal times and bed times. There is, therefore, no link between bad parenting (on this measure) and material poverty.

These two facts suggest another, bigger reason for child poverty. Quite simply, it has become harder for less skilled people to provide for their families. For someone at the 25th percentile of weekly wages, real wages are 6% lower now than they were as far back as 1997*.

In this sense, obstinately high child poverty has its roots in developments in the labour market. Whether it be because of mass unemployment**, deindustialization, the offshoring of low-skilled work, technical change or whatever, the fact is that things have gotten tougher for what used to be called the respectable poor in the last 40-odd years.

It is this fact that Duncan Smith seems to want to gloss over. From the point of view of the ruling class, it is better to question the character of the poor than the health of capitalism. And, sadly, I fear he might succeed in this aim: the egocentric bias means many voters like to think well of themselves and hence less well of others. There will therefore be an audience for slanders against the poor.

However, facts are facts however you try to change the language. You can define your cow as a horse but it still won't win the Derby.

* According to ASHE, gross weekly earnings for the 25th percentile have risen 53.6% since 1997 (when their data begins) whilst the RPI has risen 63.6%: I suspect RPI is a better measure than CPI as it includes housing costs.

** There are 1.81 million officially unemployed, plus 1.3m part-timer workers who want full-time work, plus 2.34m economically "inactive" who want a job. That's a total of 5.45 million.

Another thing: insofar as some poor parents are lazy, there's a question of endogeneity: is the laziness a cause of poverty or is it instead an adaptive preference - a response to their belief that they can't find work?

June 30, 2015

Inequality, the state & the left

To what extent can the state be used to advance leftist aims? This is one of the questions posed by the Greek crisis. But two things I've seen recently suggest the left in the UK should also be asking this.

First, Fraser Nelson points out that kids who attend schools in the poorest areas are significantly less likely to get five good GCSEs than those in better-off areas. In this sense, state schooling is inegalitarian. As Heather Rolfe says, poor white kids get a poor deal from education.

Secondly, the ONS says that in 2013-14 the poorest fifth of households paid a higher proportion of their income in tax than the richest fifth: 37.8% against 34.8%. The tax system is not progressive.

Of course, the state is a force for equality in other ways - there is still a welfare state. But these facts remind us that government is not that egalitarian and can actually be a force for increased inequality.

This will, of course, be no surprise to Marxists."The executive of the modern state is but a committee for managing the common affairs of the whole bourgeoisie" wrote Marx and Engels: "The working class cannot simply lay hold of the ready-made state machinery, and wield it for its own purposes." There has always been a strong strand of libertarianism within Marxism.

A big reason for this is that the rich often have the power to ensure that the state operates in their own interests. The revolving door between Whitehall and big business ensures that policy favours the latter. The fact that the government wants to create jobs and a tax base makes in want to protect business confidence. And globalization and/or neoliberal ideology lead to a reluctance to tax the rich heavily.

In the face of pressures such as these, I fear that the statist left is often guilty of wishful thinking - of what I've called Bonnie Tyler syndrome, of holding out for a hero who can wield the state for egalitarian purposes.

But this is naive: what we saw this year in Ferguson only confirmed what we saw during the miners' strike - that, in the wrong hands, the state will be viciously regressive.

Rather than merely hope that the state can be grasped by good people, the left needs to think differently. What we also need are horizontalism or what Erik Olin Wright has called (pdf) interstitial transformations - self-help groups independent of the state which can grow to supplant capitalism or at least act as a counterweight to capitalistic pressures.

Sadly, though, I'm not sure that much of the British left is thinking along these lines. Perhaps, though, real progress towards socialism will occur only when the left begins to question its love of the state.

June 28, 2015

Inequality: the right's problem

Are trends in UK inequality more of a problem for the right than left?

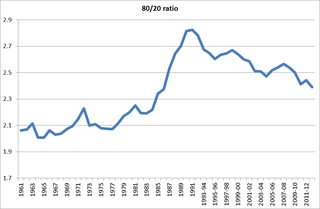

I'm prompted to ask by the fact that recent years have seen two different trends. On the one hand, there's been increased equality between the moderately well-off and the moderately badly off: the 90/10 and 80/20 ratios for post-tax income have fallen back to 1980s' levels. But on the other hand, top incomes have risen; although the share of incomes going to the top 1% (Excel) has fallen since the recession, it is twice what it was in the mid-70s.

One could argue that both these trends should worry the right more than the left. After all, luck egalitarians and Marxists, for different reasons, thought capitalism was unjust 30-40 years ago; subsequent developments won't have changed their minds. The right, however, should be disquieted.

They should be concerned by the relative decline of the middle class partly because a narrowing gap between them and the worse off dampens incentives to work harder or get an education, but also because, historically, a healthy and optimistic middle class has been the bedrock of freedom.

It might be no accident that the relative decline of the middle class has led to anti-market attitudes: not only do the majority of people favour immigration controls, but sizeable minorities of social classes ABC1 support controls over rents and even food prices (41% and 33% respectively according to one poll (pdf).)

It's also reasonable for free marketeers to be concerned about rising top incomes.

In this context, the statistics are meaningless. A given level of inequality can arise from processes which free marketeers would think benign, such as differences in choices over work and savings or the emergence of superstars, as in Nozick's famous Wilt Chamberlain example. Or it might arise though processes they would deplore, such as rigged markets or cronyism. What matters is not the level of inequality but rather how it arose.

And it's plausible that at least some of the rise in inequality is due to the latter. Bankers have been (increasingly) well-paid since the 80s because they have exploited the implicit state subsidy they get from banks being too big to fail. And the fact that CEO pay has risen without obvious improvements in corporate performance is consistent with the possibility that corporate governance failures have facilitated increased rent-seeking within what are, in effect, centrally planned economies*.

The very fact that a rising income share of the 1% has been followed by a worsening macroeconomic performance (in the sense of slower growth in GDP per head) since the 90s should alert us to the possibility that malign processes have been behind the rise in inequality. This might perhaps (only perhaps (pdf)) be because the state subsidy causes finance to become too big (pdf) with detrimental effects on growth; or because the managerialism that raises bosses' incomes strangles productivity and innovation or because inequality reduces the trust which is necessary for decent economic growth.

Now, I concede that generalizations here are unhelpful; from a free market perspective, a rise in inequality because of the emergence of a J.K. Rowling is less troubling than an increase due to cronyism. I fear, though, that some rightists' efforts to defend inequality don't make this distinction sufficiently clear.

* One counterargument to this is the paper (pdf) by Nick Bloom and colleagues which claims that rising US inequality is due to increased inequality between firms rather than between workers in the same firm. I'm not sure what to make of this. If, say, a bank subcontracts its cleaning work, intra-firm wage inequality falls whilst inter-firm inequality rises. But has anything substantive really happened? For other criticisms of this paper, see here (pdf) and here.

June 25, 2015

Managerialism vs innovation

Does management's pursuit of efficiency crowd out innovation? I ask because of two interviews I've seen recently.

First is Matt Ridley's with Hon Lik, inventor of the e-cigarette, which describes how Mr Lik's invention was inspired by his own desire to quit smoking and facilitated by the fact that the "lab where he worked had a good supply of pure nicotine".

Secondly, Toru Iwatani, the creator of Pac Man, tells the FT:

Japanese game companies used to be places of total freedom. We had almost no orders, except to make fun games.

Mr Iwatani, says the FT, is "the product of a typical Japanese company structure that insulated people such as him from job insecurity and thus incubated creativity."

What we have here are two case where innovation occurred in situations which would horrify many Anglo-Saxon managers. Allowing employees to use company materials for their own personal pet projects as Mr Lik did, or giving them jobs for life and little oversight as Mr Iwatani enjoyed, aren't generally considered good management practices. And yet they produced important creations.

This point might generalize. If you have your nose to the grindstone and are working flat out, you might be very efficient but you don't have the time to experiment with new ideas.

For this reason, many innovative companies give employees space to follow pet projects: think of 3M's bootlegging (pdf), Google's 20% time, Microsoft's Garage or Apple's Blue Sky. These recognise the fact that orthodox managerialist structures, with their emphasis upon cost-effectiveness and following routine and protocols, militate against creativity. Employees thus need some protection from managerialism if they are to innovate.

Hence my question. Could it be that the spread of managerialism and the pursuit of "efficiency" in the static sense of trying to maximize output for given inputs has squeezed out innovation?*

Two things suggest an affirmative answer. One is casual empiricism: the growth of managerialism has been followed by a decline in trend labour productivity growth. The other is a paper from David Audretsch and colleagues, which shows that since the late 70s innovation has tended to come less from incumbent firms and more from new ventures.

If this is the case, then perhaps secular stagnation is not so much an aberrant feature of hierarchical capitalism as its logical consequence. I've said that stagnation might be the result of firms' wising up to the fact that a lot of innovation doesn't pay. But it might also be due to managerialism squeezing out the slack space in which innovation can occur.

Perhaps, then, Marx was right: whereas for a long time capitalism promoted growth, it no longer does so. As he put it:

At a certain stage of development, the material productive forces of society come into conflict with the existing relations of production or ��� this merely expresses the same thing in legal terms ��� with the property relations within the framework of which they have operated hitherto. From forms of development of the productive forces these relations turn into their fetters.

I say all this to endorse a point made by Mariana Mazzucato - that the Labour party can no longer assume that the economy will grow nicely but must instead put in place the policies and institutions that generate such growth. How compatible such institutions are with managerialist capitalism is, however, an open question - and one which Labour isn't even asking.

* My question is consistent with John Kay's theory of obliquity: maybe growth and innovation are unintended consequences which are stifled by attempts at conscious control.

June 8, 2015

Tories against freedom

To those of us whose political instincts were formed in the 70s and 80s, today's Tories present a strange spectacle.

What I mean is that Thatcherites presented themselves as being on the side of liberty: after she died, The Economist called Lady Thatcher freedom fighter and the Telegraph a "champion of liberty." However, the same cannot be said for today's Tories, for at least three reasons:

- Osborne's call for a crackdown on those who ���spread hate but do not break laws���and Cameron's rejection of the idea that the state should leave us alone as long as we obey the law are both antithetical to the Thatcherite principle of liberty under the rule of law.

- Some Tories want to restrict freedom of movement within the EU. Whereas Tebbit wanted workers to get on the bikes, his successors want to stop them doing so.

- The proposed ban on legal highs, as it currently stands, is a proposal to prohibit pretty much anything.

In these senses, the government is continuing the trend of the coailition and New Labour - to create ever-more new criminal offences. Today's Tories are the enemies of liberty, not its champions. As Bruce says, a truly Tory government should be reversing authoritarianism, not increasing it.

This poses the question: what has changed since Thatcher's time?

The answer could be: nothing. Thatcherites' failure to vigorously oppose apartheid, section 28 and the desire to starve the IRA of the "oxygen of publicity" all suggest that they believed in freedom only for particular types of people.

But there's another possibility - that managerialism has beaten the idea of spontaneous order. The case for freedom rests, to a large extent, upon the idea that people left to themselves will sort things out more or less adequately. Although this idea is associated with economics - think of Smith's invisible hand - it goes much wider than that. The Millian case for freedom of expression is that good arguments will drive out bad - that Islamofascism in Britain can be beaten by open debate.

Today, though, spontaneous order has very few adherents.

Herein, though, lies a problem. If a government promises a perfect world in which we are protected from foreigners, dangerous talk and people having a good time it will swiftly lose legitimacy when people realize that those promises cannot be delivered.

Maybe Thatcherites' talk of freedom was hypocritical. But hypocrisy is the tribute that vice pays to virtue. And there was a good reason for Thatcherites to claim to support liberty.

June 6, 2015

"A nice guy"

Jon Snow's claim that Tariq Aziz was a "nice guy" has been widely attacked: Nick Cohen called it "everything that's wrong with the British Left handily summarised in one tweet."

But what exactly is the error here? I don't think Snow is defending the Saddam regime: it's no defence of a murderous tyranny to claim that one of its members seemed like a decent bloke.

Instead, I suspect there might be one of two different mistakes - each of which is quite common.

One arises from the fact that, in judging Aziz's character, the personal impression he made on meeting him is only a fraction of the total information available. Any reasonable assessment would ask: would someone spend decades as a key member of a brutal dictatorship if he really were a nice guy?

The answer is: perhaps not. Even if Aziz started as a decent bloke, he might well have been corrupted by proximity to the worst form of power.

Snow seems therefore to be overweighting private information and underweighting public information.

But as I say, this is a common mistake: it's closely related to that most ubiquitous cognitive bias, overconfidence. We see often see it in financial markets. For example:

- The neglect of base rate information - for example the tendency for many takeovers to fail - and overweighting of private information ("this acquisition seems a good idea") can lead to catastrophically expensive takeovers, such as RBS's of ABN Amro.

- Investors often pay too much (pdf) for newly-floated companies because they overweight their private feelings and underweight an obvious public signal: if this is such a good business, why are the people who know it best selling it?

- One reason for momentum in asset prices is that people cling to their prior private beliefs. For example, if bad news hits a company, its owners are loath to sell because they cleave to the belief that it's a good stock. This causes prices to under-react to bad news, and so drift down in subsequent weeks.

Let's though, ignore all this and assume that Aziz really was a nice guy. The fact remains that his life did not improve the condition of humanity. And this poses a question: to what extent does character matter?

Adam Smith thought not."It is not from the benevolence of the butcher, the brewer, or the baker, that we expect our dinner, but from their regard to their own interest" he wrote. Marx agreed. The well-being of workers, he said, "does not, indeed, depend on the good or ill will of the individual capitalist." Both instead thought incentives and social structures were more important that individual dispositions - though they differed upon the effect that capitalist incentives had. And the famous experiments of Philip Zimbardo surely corroborate them.

In calling Aziz "a nice guy in a nasty situation" Snow might have been acknowledging this. But I fear he was underestimating the extent to which some situations are so nasty that they render individual character irrelevant. Again, this is a variant of a common cognitive bias: the salience heuristic leads us to overweight obvious information - the impression a guy makes on us - and underweight less salient facts such as how social structures and incentives shape behaviour.

And again, Snow's error is common. Lefties commonly attack bankers and top footballers as greedy, when in fact their wealth arises not from greed but from the structure of 21st century capitalism.

In these ways, I'm sympathetic to Nick's point: Snow's tweet does express a lot that's wrong with how many people think about society.

June 5, 2015

Mismanaging public finances

For years, Keynesian have complained that governments must not treat the public finances as if they were household finances. This complaint lets the government off too lightly, because no sensible household would manage its finances in the way the government does.

Take three recent examples.

First, Osborne promised yesterday to sell the government's stake in Royal Mail to reduce government debt.

This makes no sense. The expected return on that stake should be positive, simply because if the market is valuing Royal Mail fairly its returns should be more or less those of the stock market generally. However, the government is borrowing at a negative real interest rate. Selling a positive-returning asset to pay off costless debt is just daft. It's like a tradesman selling his van and tools to reduce a mortgage whose payments he can easily afford. Nobody would so that.

Of course, selling the stake might make sense if you thought Royal Mail were overvalued or if you expect borrowing costs to rise sharply. But the market does not expect the latter. And the fact that the government sold Royal Mail so cheaply in the first place suggests it has no especial knowledge about its value.

Secondly, Radio 4's PM show has this week been running a series about NICE. This has reminded me of the government's very partial attitude to cost-benefit analysis.

If we take the NHS's drugs budget as fixed, it is entirely reasonable to use CBA to maximize its effectiveness: it's suboptimal to spend ��10,000 to give someone a few weeks of impaired life when it could instead give somebody else many years of healthy life.

But how is the drugs budget - and the NHS budget - set? It's not by careful CBA of the sort conducted by NICE but rather by politics and inter-departmental higgling. ��10,000 to give someone an extra month of life might not sound a good deal when compared to ��10,000 spent on a more effective drug. But what if the comparison is with MPs' salaries, spending on failed IT projects or handouts to Capita?

Applying CBA to only a pre-set portion of public spending is penny-wise, pound foolish. No sensible household would make best use of its food budget, whilst allocating cash between food and other things according to no good principle.

My third example is the most egregious. It's the commitment - shared by David Cameron and Liz Kendall - to spend 2% of GDP on defence.

To see how silly this is, imagine you wanted your family to eat more healthily. So you "commit" to spending 5% of your weekly household budget on fresh fruit and vegetables. You then spend ��20 on a single carrot, and as you feast on this, you celebrate meeting your commitment.

This, of course, is bonkers. You've paid no heed to value for money. No sensible household would do this. The same should be true for defence spending: what matters is having adequate military forces and value for money for what we do spend. It's what we get that matters, not what we spend. Given that defence procurement has often been massively wasteful, this distinction matters.

I'm not saying here that households are rational maximizers. It's just that they are not the gibbering idiots that they would be if they managed their finances like the government manages its.

June 4, 2015

The problem of greater equality

Inequality has fallen in the UK - which might be worrying.

This sounds like an odd thing to say. But it's the natural implication of what Ben Chu rightly says. He notes that whilst the Gini coefficient hasn't changed much since the early 90s, the share of income going to the top 1% has risen.

However, we can think of the Gini coefficient as a single measure of all inequalities: the gap between the top 1% and the second percentile, plus the gap between the second and third percentiles, and so on. For this reason, the same Gini coefficient can describe very different societies.

The Gini coefficient can therefore be stable if one inequality increases and another diminishes. As Ben says, inequality has risen in the sense that the top 1% has gotten relatively better off. But it follows, therefore, that some other inequality has fallen.

My chart, taken from the IFS, shows one of these inequalities - the ratio of the 80th to 20th percentiles, but neighbouring ratios such as the 70/30 show a similar pattern.

Now, these figures refer to incomes after tax and tax credits but before housing costs and they are adjusted for household size. A childless couple with a disposable income of ��288 per week in 2012-13 (the latest date available) was at the 20th percentile, whilst ��689 per week got the couple onto the 80th percentile; the latter is equivalent to a pre-tax income of just under ��50,000.

What's going on here, I suspect, are two separate developments.The 20th percentile are often lower-wage workers, who have benefited from tax credits: since 1996-97 their incomes have risen by 23.7% - more than any group except the 1% who got a 40% rise. However, the 80th percentile has seen growth of less than 13% - as have the 65-85th percentiles. This, I suspect reflects a combination of the relative decline of the lower middle-class and job polarization hurting white-collar workers: you can picture the 80th percentile couple as a man on ��30,000 and woman on ��20,000 - or more for a couple with kids.

In fact, I suspect their relative decline might be worse than this, because working conditions for such people might also have deteriorated.

Worse still, it's possible that robotization (pdf) will worsen their relative position still further.

And here's the thing. It's these sort of people who have, in politico-speak, worked hard and played by the rules. And yet they've seen their position decline relative both to lower-paid workers and the top 1%. Their response to this, in some (many) cases has been resentment against the political class generally: when I picture a Clarkson-loving resentful white man, it's someone on the sort of decentish wage that gets him and his family into to the 65th-85th percentiles.

It is often said that a strong middle-class is necessary for a healthy, stable free society. Insofar as this is the case, then the sort of increased equality we've seen might be a problem.

June 3, 2015

Secular stagnation as wising up

Andrew Smithers says:

A major cause of low investment is the incentives created by the bonus culture ��� the practice (now almost ubiquitous in quoted companies) of paying executives huge bonuses to reward short-term success.

I agree that many bosses are overpaid and that this is an economic problem, but I'm not sure about the mechanism Mr Smithers identifies.

Low investment and short-termism might be due not to misaligned incentives between shareholders and executives but are instead actually in shareholders' interests.

This is because creative destruction is inherently uncertain, and a rational response to such uncertainty should be to curb investment. For example, why retool a factory if future robotization will make that retooling obsolete? Why invest in a new car model if it will be supplanted by driverless cars? Why bother investing in a slightly better tablet if a rival will make an even better one?

Uncertainty should, in many cases, reduce (pdf) capital spending.

You might object that uncertainty has always been with us, so how can it explain low investment now?

Here's a theory. What we've seen since the early 00s is that firms have wised up. They know that, in the past, a lot of investment was driven by irrational overconfidence, by overly optimistic expectations for returns. They have learned from this error, and so have reduced capex.

Remember two important papers:

- William Nordhaus's finding that only a "miniscule fraction" of the total returns to innovation accrue to companies.

- Charles Lee's and Salman Arif's finding that higher capital spending leads to more earnings disappointments - which suggests that capex decisions are swayed by sentiment rather than by an improvement in genuinely profitable opportunities.

The rational response to these findings, surely, would be to become more sceptical about proposed investment plans, and thus to approve fewer of them.

Secular stagnation - in the sense of low investment even at low real interest rates - might therefore be due not (just) to a lack of profitable investment opportunities but rather to a more sober and less overconfident assessment of those opportunities. It is the result of boardrooms being dominated less by buccaneering adventurers and more by rational(ist) accountants.

Perhaps, then, we are at last seeing just what Keynes warned us of:

If the animal spirits are dimmed and the spontaneous optimism falters, leaving us to depend on nothing but a mathematical expectation, enterprise will fade and die.

Chris Dillow's Blog

- Chris Dillow's profile

- 2 followers