Chris Dillow's Blog, page 94

September 23, 2015

Piggate: the behavioural economics

Recent allegations have reminded us that some initiation ceremonies can be a little unusual. I'd be failing in my duty if I did not point out some economic aspects of this.

Such rituals are common: we see them among army recruits, football teams, primitive tribes and university students. This very ubiquity suggests that they serve a useful purpose. This has been well described by Robert Cialdini in Influence. He points out that we have a strong urge for consistency. We will therefore rationalize a humiliating initiation ceremony by persuading ourselves that the high cost of joining a society means that membership thereof being very valuable.

This was established experimentally by Elliot Aronson and Judson Mills way back in 1958. They got female students to join a discussion group, with some of them having to experience the embarrassment of reading out swear words before doing so. They found (pdf) that the embarrassed subjects valued membership of the group more highly than those who weren't embarrassed. They concluded:

Subjects who underwent a severe initiation perceived the group as being significantly more attractive than did those who underwent a mild initiation or no initiation.

Initiation rites thus act as a bonding device, making people more loyal to their fellows: Lawrence Richards is right, therefore, even though he misdescribes the mechanism through which this happens.

This is very similar to the endowment effect - our tendency to value something merely because we have sacrificed effort or money to get it. Dan Ariely calls this the Ikea effect: having suffered the eighth circle of hell in going to Ikea and then the pain of assembling their furniture, you will value it all the more. He writes:

The more work you put into something, the more ownership you begin to feel for it...On the basis of price alone, it is easy to imagine that a $4000 couch will be more comfortable than a $400 couch. (Predictably Irrational, p135,180)

The classic demonstration of this, for which Ariely won an Ig Nobel prize, was the finding that expensive placebos work better (pdf) than cheap ones.

All this has some important and general implications. Here are three:

1. Where customers are ill-informed, sellers might overcharge for products in the hope that naive buyers will interpret a high price as a sign of quality. This (as well as the fact that people are forced buyers) might help explain the huge price of textbooks and academic journals. It also explains why financial advice is expensive even though some of it is worse than useless whilst a lot of good advice can be found freely and quickly; advisors use a high price to signal quality to phools.

2. Some markets can quickly become illiquid. One reason why houses are so slow to change hands when the market weakens is that home-owners are prone to the endowment effect and so value their house far more highly than potential sellers do. As Will Goetzmann has shown, this can mean that house price indices which only measure the prices of houses that actually sell can over-estimate prices in bad times and so under-estimate the risk of home ownership.

3. We can throw good money after bad. The endowment effect and our desire for consistency can give rise to the sunk cost fallacy - our tendency to stick with a bad idea just because we've spent time and effort upon it. This is sometimes called the Concorde fallacy, because the French and British governments continued to invest in Concorde even though the project looked a poor one. It might also explain why people remain in religions, political parties and indifferent relationships - because they have invested time and effort in them.

Perhaps, therefore, piggate illuminates a much wider range of behaviour than those who are laughing at Mr Cameron would like to admit.

September 22, 2015

NIB: good economics, bad politics

There's at least one aspect of Corbynomics which many mainstream economists accept - the case for a National Investment Bank. Even critics such as John Van Reenen and the Economist see no objection to it. Indeed, Corbyn is simply adopting an idea proposed by, among others, the LSE Growth Commission (pdf) and Robert Skidelsky.

However, I fear that this is yet another example of something that is good economics but bad politics.

To see my point, remember that the Corbyn's NIB will invest not just in infrastructure but also in "the hi-tech and innovative industries of the future."

This is good economics, because it's likely that the market under-supplies investment in innovation. As William Nordhaus famously pointed out, the social returns to innovation far exceed the private returns to producers. Innovation thus has a positive externality. This means private firms will under-invest in it and so there is a case for state intervention. As Mariana Mazzucato has shown, state investments in technology can have positive spillovers to the private sector.

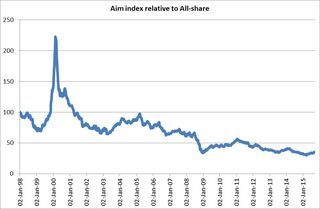

A big reason why the private returns to innovation are low is that it is a very risky business. Many apparently attractive projects will turn out to be expensive dead-ends but it is pretty much impossible to spot these in advance. William Goldman's famous saying of the movie business - "nobody knows anything" - applies generally. Two big facts tell us this. One is that the of venture capital trusts has been massively variable, with some losing fortunes. The other is that the Aim index - home to some innovative firms as well as a lot of dross - has consistently under-performed for years, which suggests that a lot of apparently promising innovations have failed.

I suspect that one reason for low corporate investment now is that firms have wised up to the fact that innovation doesn't pay.

There is, therefore a sound economic case for a NIB.

However, the same things that stop the private sector innovating mean that a NIB is bad politics.

If the NIB does its job properly it will back a lot of failures. This isn't because the state is bad at backing winners but because pretty much everyone is. Even the best private equity investors back a lot of duds: Marc Andreesen has estimated that 15 of 200 tech startups a year generate around 95% of the total returns. That leaves a lot that lose money.

And here's my problem. Our biased press will focus upon the latter. "Corbyn's bank costs taxpayers" millions would be a regular story. This could be exacerbated by the fact that the planning fallacy will ensure that even "safer" infrastructure projects will often run over time and budget. Even if the NIB is profitable on average - which perhaps it shouldn't be, given that it should be investing in projects with a high social return rather than private return - the media will present it as a failure.

Cynics might see in this a case for "people's quantitative easing". Picture the scene. Corbyn is being interviewed by some right-wing twat:

RWT: [Lists failed investments]. Your bank has cost the tax-payer millions.

Corbyn: It's not the tax-payers' money. We created the money out of thin air!

This exchange, though, merely reinforces my point - that good economics is bad politics. The NIB is therefore like immigration policy and tax policy and fiscal policy...

For this reason, I welcome Corbyn's refusal to kowtow to the media. It is only by refusing to play their silly games that we have any hope of a rational economic policy.

September 21, 2015

The outcome bias

Diego Costa has something in common with George Osborne. I don't just mean the obvious. I mean that both could be beneficiaries of a common cognitive error - the outcome bias.

Some observers are praising Costa for engineering Gabriel's sending off. "There is barely a team on the planet who would not benefit from Costa's streetfighting approach" says Oliver Kay in the Times. "He deliberately and skilfully got an opponent sent off" says Barney Ronay in the Guardian. "This was wasn���t a mugging. It was a heist, and an expert one." And Arry Redknapp adds that "you would like to have him in your team."

However, if the game had been reffed properly, Costa would have been red-carded and so Gabriel, having nobody to kick, would have stayed on the pitch. That might have cost Chelsea the game. We would not then be hearing praise for Costa, nor talk from Mourinho about emotional control.

In this sense, what we're seeing is the outcome bias. Costa's behaviour looks good not because it was skilful but because he had the good luck of having Mike Dean as ref. As Daniel Kahneman has written:

Hindsight bias has pernicious effects on the evaluations of decision-makers. It leads observers to assess the quality of a decision not by whether the process was sound but by whether its outcome was good or bad. (Thinking Fast and Slow, p203).

The outcome bias, he says, can "bring undeserved rewards to irresponsible risk seekers." Maybe Costa was one of these: he recklessly risked getting sent off himself.

This bias is a common one. It's common to praise bosses of successful companies, without asking whether that success was because of the CEO's decisions or just luck:Alex Coad's finding that corporate growth is largely random, and Ormerod and Rosewell's claim that bosses can't predict the effects of corporate strategy both suggest that we understate the latter. Here's Kahneman again:

Because luck plays a large role, the quality of leadership and management practices cannot be inferred reliably from observations of success.

A similar thing might happen in medicine: doctors get excessive praise for lucky but correct diagnoses and too much blame for reasonable but wrong ones.

Which brings me to Osborne. Some of his supporters regard the decent growth we've had had since 2013 as evidence that austerity worked. This too, is an example of the outcome bias - interpreting a bad decision as a good one simply because it eventually led to a happier outcome. But as Simon says, this is absurd:

Imagine that a government on a whim decided to close down half the economy for a year. That would be a crazy thing to do, and with only half as much produced, everyone would be much poorer. However, a year later when that half of the economy started up again, economic growth would be around 100 per cent. The government could claim that this miraculous recovery vindicated its decision to close half the economy down the previous year. That would be absurd, but it is a pretty good analogy to claiming that the recovery of 2013 vindicated the austerity of 2010.

There is, though, a problem here. The outcome bias isn't wholly stupid; as I've said, cognitive biases persist because they have a grain of usefulness. In an uncertain world, it's impossible to foresee the effects of choices and so it's hard to judge the quality of a decision at the time - especially if we don't know the decision-maker's information set. A good outcome might then alert us to the possibility that there was more wisdom in the decision than we thought at the time. I don't think this applies to Osborne's austerity - mainstream economics told us at the time that it was a bad choice - but it might apply to Costa. Maybe he judged that Mike Dean would not take a big decision to favour Arsenal and so thought he could get away with his behaviour. If so, praise for him is warranted. Sometimes, it's hard to distinguish between rational and lucky behaviour.

September 19, 2015

People's QE: no big deal

There's been much debate and, I fear, confusion, about "people's quantitative easing". Personally, I suspect the case for it all depends on the circumstances.

Let's start from a fact - that if it has any effect at all, PQE is inflationary. Whether this is a good thing or not depends upon the conditions in which it is introduced.

If PQE is undertaken when inflation and economic activity are high, then Tony is right - it would be incompatible with the Bank's mandate to keep inflation at 2%. If, however, we face the risk of deflation and/or weak activity then PQE would be entirely consistent with that mandate. In such circumstances, there is nothing radical whatsoever in the Bank buying the bonds of a National Investment Bank: the Fed's QE involved buying the bonds of government agencies such as Fannie Mae and Freddie Mac, so why shouldn't the Bank do the same?

Doing this would not require any breach of Bank independence. Any expansion of QE would require authorization by the Treasury, and as part of this the Treasury could authorize the Bank to buy NIB bonds.

Undertaken in the appropriate conditions, therefore, there is nothing radical or unusual about PQE*.

In fact, it could be that the problem with PQE is that - if undertaken at a time of recession - it would not be radical enough. I say so for three reasons:

1. The QE element might not be very stimulative. Let's say, for concreteness, that the government announces ��50bn of investment via the NIB. This would represent an increase in aggregate demand of around 3%. This itself would tend to be inflationary: how much so depends upon how much spare capacity there will be. If this is financed by the Bank buying NIB bonds there might be an additional boost to inflation through the same mechanisms that orthodox QE added to inflation: by raising inflation expectations;by boosting asset prices as investors who get the cash reinvest it; and perhaps by weakening sterling. These mechanisms, though, might be weak. The Bank estimates (pdf) that the first ��200bn of conventional QE raised inflation by 0.75-1.5%, so ��50bn of QE might have a quarter of that impact. That's 0.2-0.4%, which isn't much.

2. PQE concedes too much to deficit financing. In saying that NIB bonds should be bought by the Bank, PQE fails to address the fact that there is massive demand for safeish assets and so a NIB can be financed at negative real rates through ordinary bond issuance.

3.There are more radical fiscal/monetary alternatives. The Bank could simply write everyone a cheque. It could, as Andrew McNally has argued, print money to allow households to buy shares. Or a mix of QE and conventional bond finance could be used to finance the creation of a sovereign wealth fund whose dividends would eventually form part of a citizens' basic income. Relative to these ideas, PQE - if introduced when monetary/fiscal stimulus is necessary - is a remarkably conservative idea.

Which poses the question: why do its advocates give us the opposite impression? One reason is that some seem to have been confused about when it would be introduced: would it be implemented in normal times or reserved for when inflation has to be raised?

Another reason is that some of them have conflated the case for PQE with attacks upon mainstream economics and, often, arguments for modern monetary theory**. These, though, are separate matters. PQE, under the right circumstances, would be a mainstream conservative policy.

* There is another issue here. One could argue that the 2% inflation target is too restrictive and that it should be lifted to, say, 4%. This would create more room for PQE. But this too is not a radical idea: it was suggested by Andy Haldane yesterday.

** It seems to me that MMT is mostly a wholly reasonable idea, undermined by the dogmatism, obscurantism and longwindedness of its advocates.

September 16, 2015

Inevitable "errors"

One of the problems with the English language is that words such as "mistake" and "error" connote shortfalls from a feasible ideal when in fact, in some important cases, errors are inevitable and unavoidable.

I'm prompted to say this by Yian Mui's piece which points out that "the Fed has continually underestimated how much support the economy needs" in the last seven years. A similar thing is true in the UK. For example, the Bank of England forecast two years ago that inflation would now be around 2% but in fact even the core rate is just 1%.

These "errors", though, are not corrigible. Macroeconomic forecasts are inevitably subject to a margin of "error". And this margin is especially big just when we need forecasts most, to warn us of recession; as Prakash Loungani pointed out in 2000 economists have a perfect record of failing to foresee recessions, a fact corroborated by subsequent experience. These "errors" aren't due merely or even mainly to economists' incompetence but to the fact that the economy is a complex process whose outcomes depend upon inherently unpredictable network effects. As GLS Shackle said years ago, accurate forecasting is pretty much impossible*.

This in turn means that monetary policy "errors" are common and inevitable, simply because policy affects the real economy and inflation with a lag - remember the title of Tony Yates' blog - and so the right policy now requires foresight as to future economic conditions.

In the absence of such foresight, though, policy will often be "wrong". The recession of 2009 implies that policy was too tight in 2007-08 and the fact that inflation now is well below its (symmetric, remember) target implies that policy was too tight some months ago.

These "errors", though, are not eliminable bugs but features; forecast-based policies will often be wrong.

It's for this reason that, like Tony, I am lukewarm about money GDP targets: I can't get excited about whether it's better for the Bank to miss a money GDP target than an inflation target.

Instead, in thinking about monetary policy we must give great weight to the inevitability that policy will be wrong.

This has, of course, long been a feature of the literature. Back in the 1960s, William Brainard said (pdf) that it meant that central banks should (pdf) be slow to change rates - a principle which the Fed followed for years. And textbooks say that central banks should (pdf) minimize a loss function. The precise form of this function is, though, debatable. Simon says that at low inflation, the Bank should put more weight upon output losses than inflation overshoots, but JP Koning says this isn't necessarily true if interest rates can become negative.

All of this leads me to why Labour would be foolish to abandon central bank independence (pdf)**.

One reason why is that the gilt market could interpret even the honest policy errors of a rate-setting Chancellor as being in fact politically motivated, by a desire to stoke up booms. This would raise inflation expectations and hence nominal interest rates. Independence removes this interpretation and hence allows rates to be lower: this, or something like it, was the argument upon which independence was founded in the 90s.

There is, though, another reason for independence. If Chancellors set interest rates the media, in its imbecile failure to see that "errors" are inevitable, would blame them for even honest and unavoidable "mistakes": imagine how much worse the criticism would be of Gordon Brown if he had been responsible for interest rates in the mid-00s. The political case for central bank independence is to ensure that somebody else is the fall guy for inevitable policy "errors".

* The fact that one or two people foresaw the crisis of 2008 doesn't refute my point. Successful monetary policy requires not that forecasts be right sometimes, but that they be right all the time. AFAIK, nobody has achieved this, even roughly.

** I mean operational independence: Richard is right that its independence is circumscribed.

September 15, 2015

What can leaders do?

Jeremy Corbyn's victory has prompted Corbynmania from his fans and talk of the collapse of the party from his critics. Both reactions beg an important question: how much difference do leaders make?

There's a famous quote from Warren Buffett:

When a management with a reputation for brilliance tackles a business with a reputation for bad economics, it is the reputation of the business that remains intact.

What he's getting at is that companies have organizational capital - cultures and ways of doing things - which are very difficult to change. The same might be true of political parties. It is rare for big established ones to collapse, Pasok and the Canadian Liberal party being notable exceptions: the thing about the Strange Death of Liberal England is that it was strange. And it is rare for them to be utterly changed: as Archie Brown points out in The Myth of the Strong Leader, transformative leaders are rare, and require especial circumstances. Those who complain about Blair moving to the right understate his orthodox social democratic achievements in, for example, reducing pensioner poverty and NHS waiting times.

In fact, Buffett is echoing something Marxists have long pointed out, that Labour is fundamentally a social democratic party which has only limited ability to change capitalism: Mr McDonnell's aspiration to transform it might be over-optimistic. One thing Miliband and Poulantzas agreed upon in their famous debate was that there are big constraints upon what parliamentary parties can do. As Miliband wrote:

Social-democrats have tended to be blind to the severity of the struggle which major advances in the transformation of the social order in progressive directions must entail. (Socialism for a Sceptical Age, p163-4)

Let's take just two of these constraints.

One is the danger of capital flight. Any government which tries to raise anything like ��120bn from companies - some estimates of the "tax gap" - would see investment collapse; ��120bn is equivalent to 30% of UK corporate profits. This greatly limits how much Corbyn can tax firms: in fairness to him, Richard Murphy recognises this.

A second constraint is ideology. Capitalism generates attitudes - cognitive biases - which serve to support the system: the media might exacerbate this process, but is not the sole cause of it. Corbyn will to some extent have to accommodate himself to this fact - and if he doesn't, his successor will. In fact, given his leftist credentials, Corbyn might be better able to do this: only a hardline anti-communist such as Nixon could have opened diplomatic relations with China during the cold war.

In this context, perhaps Yanis Varoufakis has something to offer Corbyn. He, more than most, knows just how difficult the left's job is.

I suspect, therefore that Labour will eventually revert to type, being a moderate successful social democratic party - though the journey will be, ahem, interesting. This offers both hope to the "Blairites" (a word which should be out-of-date by now) and caution to the Corbynites.

That, though, is just a suspicion, tempered by my deep antipathy towards forecasting. What I'm more confident of is that our political debate would be much improved if both sides were to question the ideology of leadershipitis and instead ask: just how much, and through what mechanisms, leaders can change parties? "Cargo cult" thinking is not good enough.

September 13, 2015

Reputation, biases & fraud

There's a link between Olivier Giroud and the financial crisis: both show the importance of reputation.

Yesterday, Giroud both missed horribly against Stoke and scored a good goal. To his detractors, the miss is evidence that Arsenal can't win the title with a second-rate striker. His fans, by contrast, look at the goal as evidence that he is good enough. What both are doing is seeing his performance through the prism of their priors; if you think Giroud is mediocre, you focus upon his shortcomings but if you like him you see his merits*.

This is how reputations are built. If you have a good reputation, a mix of the framing effect and confirmation bias means that people will read ambiguous evidence as compatible with that reputation. And if you have a bad reputation, they'll interpret the same ambiguous evidence as consistent with you being a duffer.

Reputations, though, are assets and assets can be exploited; as the old saying goes, "give a man a reputation as an early riser and he can sleep til noon."

One of the best examples of this in sport was Shane Warne's later career. His reputation as a magician so bamboozled batsman that he could take wickets even with ordinary straight balls.

A similar thing happens in music; a reputation as a great artist allows some performers to make self-indulgent albums: think of the more, cough, challenging music of Lou Reed, Prince or Scott Walker.

Conmen know this. One of the oldest frauds is the confidence trick. You win the confidence of the mark, for example, by repaying small loans with interest and then use this reputation as a good borrower to borrow a fortune and run off with it.

In Phishing for Phools, George Akerlof and Robert Shiller call this reputation mining:

If I have a reputation for selling beautiful ripe avocados I have an opportunity. I can sell you a mediocre avocado at the price you would pay for the perfect ripe one.

This, they say, is just what ratings agencies and investment banks did in the 00s. They used their good reputations to give high credit ratings to bad securities, thus passing off bad avocados as good ones.

Such behaviour isn't, though, confined to the financial sector. Luigi Zingales and colleagues have estimated that around one-in-seven US companies might be defrauding their shareholders by bosses' exploiting their reputations for trustworthiness.

The problem here, though, isn't simply outright dishonesty. Even wholly honest corporate bosses and fund managers use inflated reputations for excellence to earn big salaries and fees. And companies can profit - for a while - by selling inferior goods under a good brand name: its critics claim that this is what has happened to Cadbury's chocolate.

My point here is that exactly the same processes that we see among football supporters - a tendency to use cognitive biases such as Bayesian conservatism and the confirmation bias to build reputations which aren't always proportioned to evidence - also exist in economics, and sometimes with unpleasant effects. Economics and sport have much in common; in fact, I regard Matthew Syed and Ed Smith as our best economics journalists.

You might think all this just shows the dangers of having strong prior beliefs about people's competence and trustworthiness.

Maybe. But there are dangers in not having priors. There's a rare phenomenon known as the Capgras delusion, whereby people believe their close relatives have been replaced by impostors. When psychiatrists quiz such patients, they often reply along the lines that such events are indeed improbable but they must believe the "evidence" of their own eyes. To such patients, more faith in their priors - that people don't get replaced by impostors - would enhance their psychological health.

Good judgment requires us to hit the happy medium, putting neither too much nor too little weight upon our priors.It's because this is so darned difficult that costly cognitive biases are so ubiquitous.

* In fact Giroud's goals-per-game ratio, at 0.42, whilst less than that of the best strikers, is comparable to that of some lauded ones such as Carlos Tevez and Didier Drogba (and, ahem, Emmanuel Adebayor).

September 12, 2015

Corbyn's victory, the Bubble's defeat

Was this a victory for Jeremy Corbyn or a defeat for the Westminster Bubble? I ask because of three different but related things.

One is organizational. Many New Labour figures supported the introduction (pdf) of registered supporters as a means of weakening the influence of activists and union leaders - of avoiding "stitch-ups by special interest groups". It turns out that that innovation bit them on the arse as it was those registered supporters who delivered Corbyn's victory.

A second sense is partly organizational and partly ideological. New Labour and the media promoted an ideology of "strong" leadership, the upshot of which is that leadership elections become high-stakes winner-take-all contests. If Labour had a more collegiate leadership system, the Bubble would at least have lost less in this election.

Thirdly, Corbyn's success, I suspect, owes a lot to the perception that he was the anti-Bubble candidate. Without him, the leadership contest would have been an unspiring low-grade marketing exercise, uplifted only by the under-rated Liz Kendall's ideas of empowerment and popular control. What the Bubble overlooked was that talk of appealing to the centre ground beg the question of whether the terms "left, right and centre" have a clear meaning any more. Many voters, for example, support both austerity and redistribution, and nationalization and immigration controls: does that make them left or right, or what?

In the fetid atmosphere of bland and unempirical marketing-speak of making Labour electable, Corbyn was a breath of fresh air. He asked questions that matter to those of us outside the Bubble: how to increase investment and living standards? I find his answers to those questions uninspiring. But when one of his rivals can only say "vote for me coz I'm a woman", it's easy to see why so many people think otherwise.

Let's remind ourselves of a big fact. Corbyn has been an MP for 32 years and for 31 and three-quarters of those nobody talked of him as a potential Labour leader. That he now occupies that role owes less to his own merits than to the weaknesses of the alternatives.

There is, though, perhaps a bigger message here. As Owen says, Corbyn's popularity shows that history "doesn���t unfold in ways you can control." Social and political affairs are complex emergent processes the outcome of which often cannot be controlled or foreseen by "experts." In this sense, too, Corbyn's victory is a defeat for managerialism. I therefore agree with Paul; although I am unenthusiastic about Corbyn the leader, I welcome (I think) the processes that put him in place.

September 11, 2015

Filters

What are the filters? Some things I've seen recently make me think this question should be asked more often in politics and the social sciences.

What I mean is that all social structures - markets or the state, hierarchies or coops - act as filters: they select for some behaviours and against others. The question is: which ones?

Standard Econ 101 tells us that, under some circumstances, free markets filter in activities which maximize efficiency and consumer welfare and filter out sub-optimal ones.

However, these circumstances are not ubiquitous. Nick Bloom and John Van Reenen have shown (pdf) that there are "a large number of firms who appear to be extremely badly managed" - which means that actually-existing markets don't wholly filter out inefficiencies. In their new book Phishing for Phools George Akerlof and Robert Shiller describe how, markets select not for welfare-enhancing behaviour but for "manipulation and deception." And we have several models - ranging from Akerlof's market for lemons to Tervio's talent markets and Witte's survival of the unfittest theory - which show that markets can filter in bad products, mediocre employees and lucky bluffers rather than filter them out.

However, inadequate or counter-productive filters are not just a problem in some markets. They are also a problem in hierarchies. The Dilbert and Peter principles (pdf) tell us that firms promote incompetents, in part because managers lack the ability to spot ability.

Bad or missing filters are also a feature of government and policy-making. When Simon and I talk about bubblethink and mediamacro we are complaining that the media filters good economics out of public discourse and bad economics in; the Overton window is an example of a bad filter.

If the media is a bad filter, there's also a missing filter in policy-making, as Simon says:

I think most people imagine politicians outside government as having at their disposal a huge network of assistants, each of which is plugged into a huge network of advice coming from individuals and think tanks. There is certainly a huge amount of advice out there, but you need some knowledge to filter good from bad, research based ideas from ideological ones etc. And that is the problem: there is no army of experienced assistants doing that job.

My point here is partly to remind us of the old truism that there is failure in markets as well as governments. But it's also to endorse points made recently by Arnold Kling and Dani Rodrik. Economics, they say, should not be (just) about model-building but model selection. In my context, this means asking whether models of good filters, such as textbook perfect competition, are more applicable than models of bad filters. The answer, of course, will vary from place to place - a fact obvious to all but silly ideologues.

If we were serious about improving markets and the state, we would focus much more upon the question I began with. We'd ask of particular markets and state functions: what behaviour is filtered out and what in, and how can we improve these filters? I fear, though, that the bad filters which select against good policy-making prevent this question gaining the prominence it deserves.

August 25, 2015

Nothing to fear but...

Yesterday's big stock market falls pose the question: do we really have anything to worry about?

It's tempting to answer: no. The claim that stock markets have predicted nine of the last five recessions is a cliche because it is true - although why (pdf) this is is a matter of doubt. And we know from the very mild repercussions of the tech crash of the early 00s that exogenous falls in share prices don't have catastrophically negative wealth effects.

Nevertheless, I suspect there are four concerns here.

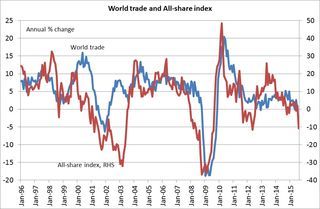

First, the fact that the Chinese economy is slowing down (pdf) is a symptom that world trade generally is stagnating; although today's figures from the CPB showed a good increase in this in June, the volume of world imports is still lower than it was last autumn. This means that a major force for the world's enrichment - an increased global division of labour - is now absent. Unsurprisingly, there's a close correlation between annual growth in world trade and annual returns on UK shares.

Secondly, we don't know how much further the world economy might weaken. Granted, the stock market is a lousy predictor of recessions. But so too is pretty much everything else (except perhaps the yield curve). Back in 2000, the IMF's Prakash Loungani wrote (pdf) that mainstream forecasters' "record of failure to predict recessions is virtually unblemished": the recession of 2008-09 merely corroborated this. Maybe recessions are inherently unpredictable because they arise from unknowable network effects.

Thirdly, a highly indebted (pdf) world increases the danger of a financial crisis. Someone, somewhere has leveraged exposure to commodities and commodity producers. If that someone is highly interconnected with other funds, there's a danger that their collapse will trigger others, via heightened counterparty or fire sale risk. The question is: will the collapse be like that of LTCM, which had big spillovers or like that of Amaranth, which didn't? (I stress that what matters is not so much the level of total debt as the distribution thereof .)

Fourthly, there's less chance than before that macroeconomic policy could stabilize economies in the event of recession or financial crisis. Conventional QE is less effective when bond yields are low. And governments' commitment to austerity makes it less likely that we'd get timely countercyclical fiscal policy.

Now, I don't say all this to offer reasons to expect shares to fall further. It's also a cliche because it's true that bull markets climb a wall of worry. If you want comfort, the fact that yield curves are upward-sloping points to us avoiding recession. Personally, I think most efforts to time the market beyond obeying the "sell in May, buy on Halloween" rule are mistaken.

Instead, my point is a simple one that's been made before. It's that stock markets' falls remind us that high leverage, financial interconnectedness and the zero bound all combine to make us vulnerable to recession or crisis.

Chris Dillow's Blog

- Chris Dillow's profile

- 2 followers