Chris Dillow's Blog, page 92

October 23, 2015

Osborne: the Katie Hopkins Chancellor

Most Chancellors have intellectual influences and mentors. Dalton and his successors had Keynes, Howe had Friedman, and Brown had several east coast US economists. Who, then, is George Osborne's influence? The answer is...

Katie Hopkins.

Her schtick is simple: imagine what reasonable people believe, and then say the opposite. Osborne is copying this. For example:

Reasonable people: use negative real interest rates to borrow cheaply. Osborne: borrow from China and pensioners at unnecessarily high cost.

Reasonable people: build more houses. Osborne: stoke up even more demand through Help to Buy.

Reasonable people: raise the minimum wage carefully and on the basis of evidence and research. Osborne: jack it up as political grandstanding.

Reasonable people: incentivize work and support the low-paid through tax credits. Osborne: cut tax credits.

Reasonable people: ensure that governments have discretion to loosen fiscal policy if needed. Osborne: legislate for a return to surplus regardless of economic conditions.

Reasonable people: delay fiscal austerity until interest rates are above the zero bound. Osborne: implement it anyway, even if it is self-defeating.

Reasonable people: if you must cut public spending, do so after consulting workers about where waste can be identified, and after studying best practice in public services around the world. Osborne: cut anyway and hope for the best.

This, I think, explains something. Osborne's policies generally lack consistent support from economists. Of course, there are some that support austerity, and some that support the higher minimum wage. But I suspect there isn't a single one who supports both. This seems puzzling. However, once we regard him as a Hopkinsite, the puzzle vanishes: he is perfectly consistent.

October 22, 2015

Markets need Marxism

Trading in house price futures would stabilize house prices and increase households' welfare, according to new Bank of England research. This poses the question: why isn't there an active market in such instruments?

It's certainly not because their virtues are not known. Robert Shiller pointed out over 20 years ago that macro markets - assets whose prices were linked to GDP, house prices or industry or occupational incomes - could spread risk. And yet these markets barely exist at all. Why not?

One reason is bad incentives. The financial "services" industry has more incentive to sell overpriced rubbish such as complex credit derivatives, structured products and actively managed funds rather than good assets. As Akerlof and Shiller say: "competitive markets by their very nature spawn deception and trickery (p165)."

Also, there is a collective action problem in establishing new markets. A good market needs liquidity. But if people fear that liquidity will be weak or absent, they'll not participate in the market, so it will indeed fail to develop.

In his excellent book, An Engine Not A Camera (pdf) Donald MacKenzie describes how Leo Melamed, boss of the CME, overcame this problem in the early days of index futures by cajoling traders into trading them, thus creating the necessary liquidity:

A market, says Melamed, ���is more than a bright idea. It takes planning, calculation, arm-twisting, and tenacity to get a market up and going. Even when it���s chugging along, it has to be cranked and pushed.��� (p173)

Sadly, though, we often lack Melameds. When we do, we might need state intervention to solve the collective action problem. For example, the Bank of England could encourage the development of house price futures by giving them to households as part of its next quantitative easing policy - or, at least, it could provide easy credit facilities with which to buy them*.

You might find it odd that state intervention is necessary for the development of free, well-functioning markets. You shouldn't. As Karl Polanyi pointed out (ch 5 of this pdf), it was state intervention which drove the development of markets in the 15th and 16th centuries. David Graeber writes:

Despite the dogged liberal assumption...that the existence of states and markets are somehow opposed, the historical record implies that the exact opposite is the case. Stateless societies tend also to be without markets (Debt: the first 5000 years, p50)

All this poses the question. Why, then, haven't we seen state help to create what Robert Shiller has called financial democracy?

It's certainly not because of a commitment to laissez-faire: the massive implicit subsidy to banks tells us that the state is very happy to intervene in the financial system.

Instead, the answer was pointed out by Marx: the state serves the interests of capitalists, not the people. And financial capital would rather financial markets consisted of rent-seeking than of enhancing aggregate welfare. Crony capitalism has encouraged financialization (pdf), not financial democracy.

In this sense, a well-functioning market economy requires that the state be freed from the grip of capitalists. In some respects it is capitalism that is the enemy of a market economy, and Marxism that is its friend.

* This is just a variant on Andrew McNally's proposal to extend equity ownership.

October 21, 2015

Tax credits: the Bubble's failures

Despite winning last night's Commons vote, George Osborne is still under pressure from many on the right to reverse his cuts in tax credits. This highlights two failures of the Westminster Bubble.

The first failure was that it misjudged July's Budget in which Osborne announced those cuts.

The initial reaction to that Budget was generally favourable. It "gives Britain a pay rise" said the Telegraph. It "stole Labour's clothes" said the Guardian's Jonathan Freedland. And Jeremy Warner welcomed "the best Labour Budget in a long while". Even the BBC got in on the act. Tory stooge Robert Peston wibbled about the extent to which cuts in tax credits would be offset by the higher minimum wage but omitted to tell viewers that this offset would be only partial.

Such cheerleading simply misread facts which were available at the time.The NIESR, SMF and Resolution Foundation immediately spotted that the cuts to tax credits would inflict hardship - and, in fairness, one or two journalists did too.

What we saw in July was yet another example of the big gulf between reality and the Bubble. What we're seeing now is the fact that reality, inconveniently, refuses to go away.

To see the second failure of the Bubble, recall why Osborne thought cuts in tax credits were necessary. It's because his original plans to cut departmental spending were simply not credible. He felt he had to cut tax credits because he couldn't sufficiently cut other forms of spending. His announcement of cuts in tax credits in July was accompanied by increases in plans for other spending - a ��21.3bn rise in non-welfare spending for 2019-20.

But why were his original plans incredible? One reason is that he had failed to provide any political foundation for them; he hadn't created an ideological climate conducive to a small state, nor mobilized the dispersed fragmentary knowledge of workers who could identify efficiency savings.

He failed to see that big political change requires more than bums on seats in Whitehall. It rests upon broader social conditions. The Bubble, with its focus upon Westminster, under-estimates this fact. In this sense, some Corbynistas - who see that there's much more to politics than Westminster - know something the Bubble is keen to deny.

October 20, 2015

Steel, & austerity denial

A few days ago, I accused Tories of being "oblivious to problems of weak demand". Not just Tories, it seems, but the media too.

I say this because its coverage of the closure of steel works is blaming these upon, variously, Chinese dumping, high energy costs and the global slowdown.

But there's something missing from this list: fiscal austerity.

Simon has estimated that this has cost the UK economy 5% of GDP, and the euro zone a similar amount. It's reasonable to suppose that if European GDP were 5% higher then there'd be more demand for steel and so the industry would be in better shape. I'm not saying all would be well, but the odds would at least be more favourable to it and, at worst, laid-off workers would have more chance of finding new jobs.

This point, however, is being missed. Instead, we get this from business minister Anna Soubry:

The steel industry across the UK is facing very challenging economic conditions...government cannot alter these conditions."

As if government cannot influence aggregate demand! Instead, in blaming high energy costs for steel's woes, the press give the impression that greens are responsible whist the government is a powerless onlooker.

What's going on here is deeply ideological. Weak demand is being presented as something natural and immutable, rather than what it is - a policy choice. The costs of that choice, however, are not mere statistics - a few per cent of GDP - but people's livelihoods and communities.

You might think I'm making a leftist point here. Not entirely. There is in fact a free market case for high aggregate demand policies.

Such policies would fend off calls for government action to save the steel industry. This isn't because high demand would have stopped the industry slumping. Maybe it wouldn't. But if the industry were collapsing at a time of high demand it would be clearer that the industry needed to shrink in response to changing markets, and it would be easier for sacked workers to find new jobs. By contrast, state aid for specific industries is more market-unfriendly, as it risks preserving the economy in aspic and gives special favours to those who have lobbying power.

Insofar as the alternative to fiscal activism is ad hoc state intervention in particular industries, one would expect free marketeers to be most vociferous in their hostility to austerity. As I've said, the demise of small government Keynesianism is one of the oddities of our era - and, I think, a regrettable one.

October 17, 2015

Technical change as collective action problem

Stephen Hawking has reminded us of why Marx is so relevant today. He's written:

If machines produce everything we need, the outcome will depend on how things are distributed. Everyone can enjoy a life of luxurious leisure if the machine-produced wealth is shared, or most people can end up miserably poor if the machine-owners successfully lobby against wealth redistribution. So far, the trend seems to be toward the second option, with technology driving ever-increasing inequality

There is, though, a problem with this second option: if most people are miserably poor, who will buy the products of super-machines?

This raises what Marx called one of the fundamental contradictions of capitalism. On the one hand, capitalism is great at developing productive potential. But on the other, demand might not keep up with this potential:

The conditions of direct exploitation, and those of realising it, are not identical. They diverge not only in place and time, but also logically. The first are only limited by the productive power of society, the latter by the proportional relation of the various branches of production and the consumer power of society. But this last-named is not determined either by the absolute productive power, or by the absolute consumer power, but by the consumer power based on antagonistic conditions of distribution, which reduce the consumption of the bulk of society to a minimum varying within more or less narrow limits.(Capital vol III ch 15)

This can lead to two possible outcomes. One is possible "realization crises" (see eg ch X of this pdf) if capitalists over-estimate demand and invest and produce too much:

The ultimate reason for all real crises always remains the poverty and restricted consumption of the masses as opposed to the drive of capitalist production to develop the productive forces as though only the absolute consuming power of society constituted their limit. (Capital vol III ch 30)

Another possibility, though, is that capitalists might fear a lack of demand and so not invest. (In fact, this is not the only reason why they might not invest. Investment is undertaken not by a representative agent but by individual capitalists. And each individual might be loath to invest or innovate for fear that future technical progress will undercut his own innovations.)

In either of these cases, capitalism will not develop technology by as much as is technically feasible. If so::

At a certain stage of development, the material productive forces of society come into conflict with the existing relations of production...From forms of development of the productive forces these relations turn into their fetters. Then begins an era of social revolution. (Preface to A Contribution to the Critique of Political Economy)

In these ways, capitalism is a form of collective action problem. We can imagine a society in which super-machines do indeed allow us all to live in luxurious leisure. But the decentralized decisions of capitalists might not get us there.

Granted, sensible aggregate demand policies might suffice to overcome realization crises - though the believe that such policies will be enacted is a form of what I've called centrist utopianism. But the other obstacle to investment and growth - the fear of future technical change - might not be so easily soluble within the confines of capitalism.

These issues are, of course, unresolved. What is clear, though, is that Marxism presents a useful perspective upon them.

October 16, 2015

Conning the working-class

I wrote yesterday that our tendency to take people at face value leaves us vulnerable to conmen. Bang on cue, A Tory-voting recipient of tax credits spoke last night of how she felt conned by the Tories.

Deomstrating the understanding and compassion for which they are renowned, some lefties have reacted by claiming she had it coming. This ignores the powerful forces which put her into this mess.

One of these, as I've said, is that it is easy to be conned simply because our instinct is to trust people - especially those in positions of authority. As Akerlof and Shiller say, millions of people are phished for phools. There's a sucker born every minute. Hundreds of thousands of people like her were conned when Osborne lied:

Where is the fairness, we ask, for the shift-worker, leaving home in the dark hours of the early morning, who looks up at the closed blinds of their next door neighbour sleeping off a life on benefits?

When we say we're all in this together, we speak for that worker.

But there's something else. Whilst the left is right to complain that low-paid workers like that woman should have felt solidarity with benefit recipients, they should at least understand the psychological mechanisms which stop them doing so.

One of these is the self-serving bias. People adopt beliefs to enhance their self-esteem. Those on tax credits thus believe they are hard-working and deserving, unlike "scroungers" - even though they are all, from a Tory point of view, getting "the taxpayers' money."

Secondly, wishful thinking and the optimism bias lead us to think "it couldn't happen to me". As @Staedtler tweeted:

What they said: "There will be ��12 billion welfare cuts.

What you heard: "There will be ��12 billion welfare cuts for other people."

Thirdly, social comparison theory tells us that people compare themselves to those who are like them. As Leon Festinger hypothesised (pdf):

Given a range of possible persons for comparison, someone close to one's own ability or opinion will be chosen for comparison.

This is what Osborne was driving at: he was inviting the low-paid to compare themselves to their neighbours rather than to mega-rich tax-dodgers and exploiters. His invitation worked because it went with the grain of people's inclinations.

Some laboratory experiments (pdf) by Philip J. Grossman and Mana Komai have shown how strong such within-class envy can be. They show that some of the poor are willing to attack other poor people even at their own expense. They conclude:

We find strong evidence of within class envy: the rich targeting the rich and the poor targeting the poor...Within the poor community, the target of envy is usually a poorer subject whose wealth is close to the attacker; the attacker may possibly be trying to preserve his/her relative ranking.

I say all this for a reason. It's tempting for lefties to believe that people vote Tory because of "neoliberal" ideology and the right-wing media. But there might be more to it than this. Even without such propaganda, there are cognitive biases at work which undermine class solidarity. I fear some on the left underestimate this fact because of the same cognitive bias which contributed to that woman voting Tory - wishful thinking.

October 15, 2015

Believing others

One urban myth that has resurfaced recently is that of the car park attendant at Bristol Zoo who dutifully collected parking fees for 24 years only to be discovered to have been a conman who pocketed them all for himself.

There's a good reason why so many people believed this story. It's because we do tend to take people at their self-assessment and self-presentation: if a man says he's something, and he looks and acts the part, we tend to believe him.

For example, in Influence, Robert Cialdini describes an experiment in which a man asked passers-by to give a third man money to pay a parking meter; passers-by were far more likely to comply when the man was dressed as a security guard than when he was dressed normally. And in a separate experiment, Cameron Anderson and Sebastien Brion have found that people rate over-confident folk as being more competent than they are: we tend to believe people's images of themselves.

All this is no mere curiosity of psychologists' experiments. It has real political effects. For example, George Osborne has contived to present himself as being in control of the public finances and his opponents as "deficit deniers" even though his policies have failed in their own terms to cut the deficit as much as expected. David Cameron's promise last week to "end discrimination and finish the fight for real equality" was seen by some as a progressive move to the centre ground, oblivious to the fact that Tories' actual policies aren't quite so egalitarian. And the SNP has won huge support by claiming to be progressive and anti-austerity even though they are not.

All these are examples of voters and pundits believing the presentation.

I suspect that there are four mechanisms which combine to produce this.

One is that people in successful societies tend (pdf) to instinctively trust (pdf) each other. This is by no means a bad thing: trust is essential for many economic transactions and thus a contributor to healthy economies as well as good societies.

Secondly, there is simple deference. As Adam Smith famously said:

We frequently see the respectful attentions of the world more strongly directed towards the rich and the great, than towards the wise and the virtuous. (Theory of Moral Sentiments I.III.29)

I suspect that one contributor to this is the outcome bias: we assume that because someone has gotten rich or won elections they must have superior knowledge and ability, and so under-rate the role of luck.

Thirdly, as Cialdini says, there is a "deep-seated sense of duty to authority within us all"; from childhood we are brought up to identify authority - teachers and parents - with superior knowledge. However, as Stanley Milgram's famous experiments - along with much of human history - have shown, this can have terrible effects.

Finally there's a confluence of confirmation bias and social proof: once we believe something of somebody, we interpret ambiguous evidence as corroboration of that belief, and if enough people believe something of someone, then others will follow them.

Through these mechanisms, reputations can be won even if they are undeserved. And once a man has a reputation, he can use it to con people. That mythical car-park attendant and George Osborne have something in common.

October 14, 2015

More than Keynesianism

Danny Finkelstein in the Times says there's a good reason for John McDonnell's confusion on the fiscal charter:

Fundamentally, he is a socialist, not a Keynesian...The deficit may have been central to political debate over the last seven years, but it isn't central to him. So he has been careless because he regards this as a side issue.

I don't know whether this is an accurate description of Mr McDonnell. But Danny is alluding to something important here - that from a socialist point of view Keynesianism, in the sense of counter-cyclical deficit financing, is not enough.

One reason for this is simply that it does little to address what socialists regard as key defects of capitalism - its tendencies towards inequality and alienation. Danny's right to say that Keynesianism was a way of saving capitalism, not abolishing it. Sure, full employment can help ameliorate these evils by increasing workers' bargaining power. But as Kalecki famously said, full employment is not sustainable within capitalism.

A second reason - which is more pressing today than for years - is that mere counter-cyclical policy does little to increase long-term trend growth; sure it might do so by reducing the fear of recession and thus improving animal spirits, but it's also possible (pdf) that stabilization policy dampens it. Combating the threat of secular stagnation requires more than counter-cyclical policy. Keynesianism in its alternative sense of socializing investment might be part of the answer here - and in fairness this is what Corbynomics is. But only part. There's also a need for policies to raise productivity - and these might require measures to reduce inequality and increase worker ownership.

But there's a further reason why Keynesianism is not enough. Counter-cyclical fiscal policy is insufficient to fight recessions simply because recessions are unpredictable and so we cannot rely upon even a government of intelligence and goodwill to loosen policy at the right time. Anti-recessionary policy requires other institutions. These might include: nationalizing banks to prevent destabilizing credit cycles; a generous welfare state (citizens income!) to act as an automatic stabilizer; and/or Shiller-style insurance markets.

I say all this partly to answer Danny's accusation that socialism is "hazy". Lenin defined communism as "Soviet power plus electrification": I'd define socialism as citizens income plus worker ownership and control.

But I'm also speaking to the left here. It's not enough to be "anti-austerity", and certainly not enough to simply want to shift austerity onto companies and the rich - not least because pre-tax inequality matters too. Good counter-cyclical policy should of course be part of intelligent leftism. But it can only be part.

October 13, 2015

Against the fiscal charter

John McDonnell's decision to oppose Osborne's fiscal charter reminds me of what Winston Churchill said of the Americans: they will always do the right thing after they've exhausted all the alternatives.

The charter commits the government to achieving a surplus on public sector net borrowing by the end of 2019-20, which implies a tightening of around four percentage points of GDP. Mr McDonnell is right to oppose this, on three grounds.

1. It is not state-dependent. If economic growth falters, the charter would exacerbate the slowdown by imposing unnecessary austerity. As Simon has said:

Having to achieve a target at a fixed date whatever shocks hit the economy could be harmful when unexpected shocks occur near that date.

You might object that policy-makers still have counter-cyclical tools they could use such as more QE, a helicopter drop or negative interest rates. Such policies, however, have uncertain effects and so it's hard to know what the correct dosage should be. A less tight and more discretionary fiscal policy which allowed interest rates to rise would give us better protection against recession by allowing for fiscal loosening and interest rate cuts if needed - the effects of which are less uncertain.

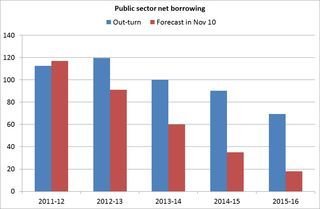

2. It could be self-defeating. As Richard says, there is still a global savings glut (or investment dearth). This means that someone, somewhere, must borrow. With real interest rates negative - implying massive demand for gilts - this someone should be the government. If it tries to cut borrowing whilst the rest of the world wants to save, the result will be self-defeating: lower GDP and hence lower tax revenues and higher-than-expected government borrowing. This is, of course, no mere possibility. It is just what's happened. In November 2010, the OBR expected PSNB to be ��18bn in 2015-16. It now expects it to be ��69.5bn, and even this might be too optimistic.

3. Given the inflation target, a tight fiscal policy implies a loose monetary policy. But this policy mix has at least two possible costs. One is that it can generate financial instability as a search for yield encourages banks and investors to take extra risk. As Larry Summers has said:

Low interest rates raise asset values and drive investors to take greater risks, making bubbles more likely.

The second cost is distributional. Loose monetary policy tends to raise asset prices thus enriching asset holders who tend to be already rich. Fiscal austerity, at least in its current form, however, bears hardest upon the worse off. To this extent, the fiscal charter would increase inequality.

Of course, the Westminster Bubble with its deficit fetishism will regard McDonnell's opposition to the charter as bad politics. Maybe. But let's remember that it is good economics.

October 11, 2015

Thoughts on the human cloud

Sarah O'Connor in the FT has a great piece on the "human cloud":

White-collar jobs are chopped into hundreds of discrete projects or tasks, then scattered into a virtual ���cloud��� of willing workers who could be anywhere in the world, so long as they have an internet connection.

A few diverse observations here:

1. The question: how far can this trend go? should be viewed through the prism of transactions costs. Coase famously showed (pdf) that firms - and therefore employees - exist because there are costs involved in market transactions, and employer-employee relationships reduced these costs.

The human cloud exists because the internet has reduced the costs of market transactions. It is now easy to find and hire someone to undertake a micro-job, and the use of ratings systems helps to solve the principal-agent problem: cloud workers are incentivized to do a good job by the desire to earn a good rating to make them attractive to subsequent hirers.

However, the obstacles to the development of the human cloud are that some costs of contracting out will remain. If a task cannot be divided from the bigger job, or if it requires constant tweaking and teamworking as job specs change, then there'll still be a place for employees.

How far the cloud can develop depends upon the precise nature of individual transactions, which will differ from firm to firm and job to job. It's not a matter of bigthink futurology.

2. This vindicates a point made by Erik Brynjolfsson and Andrew Mcafee in The Second Machine Age - that there can be a lag of many decades between the introduction of a technology and the full adoption of it. Just as it took years for firms to change to make best use of electricity, so it is only after 20 years that they are beginning to change to make full use of the internet.

3. This might contribute to the trend towards job polarization. It's low-level white collar jobs that are easiest - at first - to shift into the human cloud. This could create yet another obstacle to social mobility: it'll be harder to climb the jobs ladder if some rungs of it are missing.

4. If you no longer need to live near where you work, you'll no longer need to pay extortionate prices or rents in London but can instead live somewhere more affordable. Just as the opening of the Metropolitan line depressed house prices in central London, so too - eventually - might the human cloud.

Chris Dillow's Blog

- Chris Dillow's profile

- 2 followers