Chris Dillow's Blog, page 95

August 22, 2015

Techno-optimism & low investment

Gillian Tett points out that, despite talk of a technology boom, corporate investment is weak. This isn't as paradoxical as it seems. In fact, techno-optimism might be one reason for low investment.

I say so for a simple reason: future technical progress could well render today's investments unprofitable. If you spend ��10m installing robots in a factory today you might be able to undercut your non-robotized rivals. But if a new company later installs better robots for ��5m, it will undercut you and destroy your profits. As Marx wrote:

In addition to the material wear and tear, a machine also undergoes, what we may call a moral depreciation. It loses exchange-value, either by machines of the same sort being produced cheaper than it, or by better machines entering into competition with it...When machinery is first introduced into an industry, new methods of reproducing it more cheaply follow blow upon blow.

This is true not just of process innovation but product innovation too. For example, Nokia benefited hugely from the first wave of innovation in mobile phones, but suffered hugely from the later wave which gave us the smartphone.

The point generalizes. William Nordhaus has shown that the returns to innovation are tiny, in part because later innovations displace earlier ones. And Jeremy Greenwood and Boyan Jovanovic say that one reason for the stock market's fall in the 1970s was that investors anticipated old firms suffering (pdf) moral depreciation because of the emergence of new IT firms and methods.

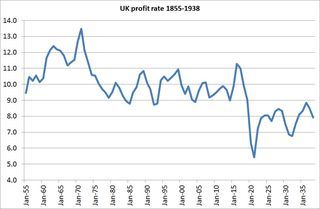

My chart shows other evidence for this. It shows the UK profit rate from 1855 to 1938*, the second industrial revolution. This was a time of phenomenal technical progress (pdf): the telegraph, the Bessemer process, electricity, steam ships, numerous chemicals, the production line, cars and radio. And yet the profit rate seems to have trended downwards after the late 1860s - consistent with later innovations destroying the profits of earlier ones.

Schumpeter called it creative destruction for a reason.

This is why I say techno-optimism might hold back capital spending: if you fear current investments will be rendered worthless by better, future ones, you'll not invest even if it is temporarily profitable to do so.

This is merely a variation upon real options theory. This tells us that, when firms face uncertainty, they will not invest even if the net present value of a project is positive, because it might become even more positive later - if, say, they can use cheaper, better technology. The idea that uncertainty holds back investment is usually discussed in terms of policy uncertainty. But uncertainty about the pace and direction of technical change can have the same effect.

Which leads me back to Marx. He said:

At a certain stage of development, the material productive forces of society come into conflict with the existing relations of production...From forms of development of the productive forces these relations turn into their fetters.

This is what we might be seeing, or are about to see. Capitalistic relations of production are fettering the development of productive forces because the fear of being unable to make a sustained profit is preventing investment in new technology.

This is no bad thing if you believe jobs are an inherently good thing and that the economy should be preserved in aspic to protect them.

There is, though, a bigger vision here - that robots can give us all a high income and free people from drudgery. It's not clear that capitalism as it presently exists can fulfill this possibility.

* My source is Mitchell's British Historical Statistics, ch XVI tables 4 and 14. You can quibble a lot with the numbers, but I suspect my broad point would survive these.

August 20, 2015

On wishful thinking

David Aaronovitch in the Times has a nice piece on how people fall for conspiracy theorists and conmen:

What a fraudster, a fantasist or a hoaxer needs to be able to survive, is to fall among people who are anxious to believe.

This urge to believe is not confined to extreme cases. It's much more common than that.

A while ago, Guy Mayraz did a neat experiment at Oxford. He asked subjects to use charts of the price of wheat to predict future price moves. Before doing so, he randomly divided them into two groups: "farmers" who would profit from a rising price, and "bakers" who would profit from a falling one. He found that farmers predicted higher prices than bakers - which is evidence of wishful thinking. What's more, this bias persisted even when subjects were given incentives for accurate predictions.

This finding applies in the real world. Brad Barber and Terrance Odean have shown that retail equity investors under-perform the market around the world in part because they tend to hold on too much to losing stocks and thus suffer adverse momentum effects; this is the disposition (pdf) effect. I suspect that one reason they do this is wishful thinking: the mere fact that they hold a share makes them unduly optimistic about it. (This is closely related to the endowment effect).

If wishful thinking exists even when people have material incentives to avoid it, it is even more likely to exist where they don't. I suspect, therefore, that it is common in politics. Political partisans are prone to over-estimate the beneficial effects of their party's policies and to under-rate the sheer difficulty of manipulating complex emergent processes such as society or the economy for the better.

Maybe, therefore, wishful thinking is more widespread than David suggests.

And in some ways, this is a good thing. In Human Inference, Richard Nisbett and Lee Ross wrote:

We probably would have few novelists, actors or scientists if all potential aspirants to these careers took action based on a normatively justifiable probability of success. We might also have few new products, new medical procedures, new political movements or new scientific theories.

And Donald Davidson has written:

Both self-deception and wishful thinking are often benign. It is neither surprising nor on the whole bad that people think better of their friends and families than a clear-eyed survey of the evidence would justify. Learning is probably more often encouraged than not by parents and teachers who overrate the intelligence of their wards. Spouses often keep things on an even keel by ignoring or overlooking the lipstick on the collar. (Elster (ed, The Multiple Self p86)

And here's the point. Because wishful thinking (like overconfidence) often has beneficial effects the learning and adverse feedback that would cause us to correct our errors is absent. Cognitive biases persist because they are not selected against, and might be selected for.

I say all this for a reason. It's very easy for those of us who write about cognitive biases to commit the Homer Simpson error: "Everyone is stupid except for me." In fact, we might in some respects be as irrational as everyone else.

August 19, 2015

Ballroom dancing, & Sapir-Whorf

Last night I went to a ballroom dance lesson, which set me thinking about the Sapir-Whorf hypothesis.

When you are a rank beginner, the natural thing to do is to speak as you are moving: "left-forward-back" and so on. But this of course confuses your partner, who must do the opposite. You can use objective locators - "to the bar", "to the window" - but whilst these work OK for the rumba, they cause a car-crash in the waltz.

What we need, I thought, are observer-neutral spatial terms - something that means "my left/your right."

Although such terms are lacking in English, they do exist in other languages. The Guugu Yithimirr of northern Queensland use points of the compass rather than subjective terms such as left or forward; they would say, for example, "the tree is west of the house."

I suspect that our ability to learn dancing would, in the initial phase at least, be enhanced if we could use such language and the thought that accompanies it - the ability to identify compass points.

This is where the Sapir-Whorf hypothesis enters. It is the theory that our language constrains our thoughts - that, as Wittgenstein said, "The limits of my language mean the limits of my world." For now at least, the English language is constraining my ability to learn to dance.

Maybe the limits on our thought imposed by subjective terms such as "left" and "right" are tighter than this. Here's a conjecture. Perhaps being accustomed to think of space in subjective language creates or intensifies an individualistic, egocentric bias in our general thinking - a tendency to think that our point of view is the objectively correct one. The fact that there are cross-cultural differences in degrees of overconfidence, perhaps because of differences (pdf) in "cognitive customs" is compatible with this hypothesis.

Here's another example. In English, we speak of the future as being in front of us; we say, for example, "I'm looking forward to my holiday". This encourages us to think that we can see the future; we can, after all see what's in front of us. But this is not the case. In important respects - such as recessions - the future is unknown and perhaps unknowable.

Here, the Aymara people have the advantage on us. They speak of the past as being in front of them and the future behind them. This makes sense: we can see the past better than the future.

Take another example. We English have no precise equivalents of the ancient Greek words for "phronesis" or "arete". It's possible that this lack is related to Alasdair MacIntyre's complaint that our moral thinking is much more confused than that of the Greeks.

Perhaps this point generalizes. It's not only language that constrains our thought but our conceptual schema. One reason why culture wars are so bitter in religion or even in macroeconomics is that different cultures have different standards of what matters - and the more bone-headed partisans don't appreciate this.

This is not to say that the constraints imposed by language and culture are tightly binding; translations are after all possible and we can construct some meaning of words like "arete". What I'm saying, though, is that we often fail to appreciate these constraints for the same reason that fish don't know that they are wet.

I guess that all I'm calling for here is a little less egocentricity in our thought and a little more effort in trying to understand where others are coming from - because perhaps our minds aren't as open as we think.

August 18, 2015

Corbynomics - meh

There are two common objections to Corbynomics (pdf) which seem to be to be misplaced.

The first is that it is out-of-date. "A howl for the past" says John van Reenen. "Old solutions to old problems" says Yvette Cooper.

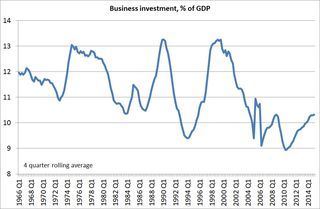

I'm not so sure. People's QE is a response to a problem which is perhaps more severe now than in the past - that the UK invests too little. The share of business investment in GDP has been trending downwards for years: complaints about BT's tardiness in rolling out fast broadband are symptomatic of a wider problem. And if fears of secular stagnation are even partly true, it might stay low. Greater public investment is a response to this.

In this sense, it might be Corbyn's critics who are out-of-date. The assumption that the private sector will generate investment, innovation and dynamism if only left alone might have been reasonable in the 90s. But it is in question today - hence, perhaps, a need for greater state activism.

The second objection is that people's QE could undermine the Bank of England's independence because it is, as Tony alleges, "pretty much orthogonal to whether it���s actually needed for monetary policy purposes."

Certainly, Corbynistas have been presenting it that way. But I'm not sure this is right. It's likely that Bank rate would be low in 2020: Mark Carney has warned that rates might peak at less than 3%, and futures markets are pricing in a rate of barely 2%. This means the Bank would have very little orthodox monetary policy ammunition to fight any deflationary shock. And there might will be such a shock not only from ordinary macroeconomic surprises but from Corbynomics itself. He wants big - possibly unachievable - tax rises on companies and the rich. These could well be deflationary. It's quite possible, therefore, that QE would be needed for conventional monetary policy purposes - to get inflation back up to 2%.

In saying all this I don't intend to wholly defend Corbynomics. I'd prefer more emphasis upon decentralized decision-making and worker control than he seems to be offering. And, paradoxically, I don't think he is sufficiently anti-austerity. Talk of people's QE dodges a big fact - that with real interest rates below zero (and expected to remain so) public investment can be easily financed through ordinary borrowing. And in wanting to close the "tax gap", Corbynistas aren't anti-austerity at all; they just think it apply to different people.

All this leaves me in an odd position. I find Corbynomics neither as good as its supporters believe nor as scary as its opponents claim. The strongest case against Corbyn becoming leader might lie outside of economics.

August 17, 2015

The C-word

One of the more irritating memes of the Labour leadership election has been the use of the word "credible". For example, Gordon Brown says "the best way of realising our high ideals is to show that we have an alternative in government that is credible." Yvette Cooper says: "We have to have a radical alternative and it also has to be credible and Jeremy's approach isn't." And Andy Burnham says Corbyn's plans "lack financial and economic credibility."

I don't like this word "credibility" because it's horribly ambiguous. It can mean four things.

First is a technical meaning: policies are "credible" if they are time-consistent. Tony Yates' objection to Corbynomics is along these lines - that in undermining Bank independence it could raise future inflation. But I'm not sure most uses of the word have this meaning.

Secondly, it could simply mean "vague". Burnham seems to have this in mind when he complains that Corbyn hasn't spelled out how to pay for free university education or nationalization. ("We'll borrow" is of course one possible and reasonable answer.)

Thirdly, it could be just a pompous sounding word for "bad" - an attempt to dress up a value judgment in apparently technocratic language. My problem with this is that it elides a crucial distinction - between policies that are unpopular and ones that would have adverse effects if implemented. The distinction matters enormously because many good policies are unpopular (eg liberal immigration, basic income, land taxes) and bad ones popular (eg deficit fetishism, benefit cuts).

The fourth possible meaning is, however, the nastiest. I fear that "credible" is often used to mean "unacceptable to the Westminster-media Bubble".

The problem with this is that the Bubble is detached from reality: it believes unthinkingly in deficit fetishism; over-estimates median incomes; and stigmatizes welfare as a cost rather than seeing it as reasonable insurance, for example. Talk of "credibility" thus means surrendering to economic illiteracy - which can hardly be the basis of good policy.

Now, I don't say all this to endorse Corbynomics. There are reasonable objections to it - not least of which is that, with real interest rates negative, there's simply no need to print money. All I'm saying is that Corbyn's opponents should not hide behind pseudo-technocratic talk of "credibility".

August 16, 2015

Inverting the rhetoric of inequality

It's not often that Sir Tom Jones provides evidence to support Mariana Mazzucato, but he's done just this.

Here's the FT's John Thornhill:

As Mazzucato explains it, the traditional way of framing the debate about wealth creation is to picture the private sector as a magnificent lion caged by the public sector. Remove the bars, and the lion roams and roars. In fact, she argues, private sector companies are rarely lions; far more often they are kittens. Managers tend to be more concerned with cutting costs, buying back their shares and maximising their share prices (and stock options) than they are in investing in research and development and boosting long-term growth.

���As soon as I started looking at these issues, I started realising how much language matters" [she says].

Coincidentally, Sir Tom complains that he was sacked from The Voice with "no conversation of any kind" - implying that BBC bosses lacked the courage to tell him to his face.

In their different ways Sir Tom and Mariana are challenging the dominant image of bosses. Far from being the swashbuckling risk-taking entrepreneurial dragons they pretend to be, bosses are often cowards who lack the courage to defend their decisions or to invest and innovate.

In fact the biggest risk-bearers are often not bosses at all, but workers. It is they who invest all or most of their biggest asset (their human capital) into a single venture. And as we saw with the collapse of City Link, small sub-contractors who are unsecured creditors can lose more than bosses do.

By contrast, bosses are often mere bureaucrats. We have long passed the point which Schumpeter described in 1942, in which the entrepreneur "is becoming just another office worker."

Now, in itself this is not necessarily a bad thing. What looks like cowardice might in fact be a rational, prudent realization that investment and innovation don't pay. And a lot of entrepreneurship is in fact a spunking away of redundancy money on doomed ventures.

What I am saying, though, is that the rhetoric of capitalism should be inverted. Bosses are not heroic risk-takers, but mere pen-pushers.

In fact, that rhetoric must also be inverted in two other ways.

First, although the right likes to paint Marxists as Stalinists and central planners, the opposite is in fact that case. It is bosses who still believe in the out-dated and discredited dogma of central planning whilst many of us leftists believe in the virtues of decentralized decision-making.

Secondly, there's a tendency to see the dichotomy between the centre and the left as synonymous with that between technocrats and idealistic dreamers. But I would argue that the opposite is the case. It is centrists who are utopians, in that they grossly over-estimate the ability of the state to improve well-being in a capitalist society. And as we heard in that notorious Jack Straw interview, centrists can be far too stupid to be technocrats.

My point here is a simple one. Inequalities are legitimated in part by an ideology which presents bosses as heroic, forward-looking wealth-creators and their opponents as dreamers and ideologues. This turns the truth on its head.The left should make more effort to reframe our language accordingly*.

You might think that, in saying this, I'm making a Marxian point. Maybe. But it was Adam Smith who complained that "We frequently the respectful attentions of the world more strongly directed towards the rich and the great, than towards the wise and the virtuous"**. I'm just suggesting we lean against this bias.

* Trades unions often exacerbate the problem. The rhetoric of "demands" presents workers as people who want to take something out of the system when the truth is the exact opposite - that workers are essential suppliers.

** Theory of Moral Sentiments, I.III.29

August 15, 2015

Fairness, decentralization & capitalism

Marxists and Conservatives have more in common than either side would like to admit. This thought occurred to me whilst reading a superb piece by Andrew Lilico.

He describes the Brams-Taylor procedure for cutting a cake in a fair way - in the sense of ensuring envy-freeness - and says that this shows that a central agency such as the state is unnecessary to achieve fairness:

Provided that all adhere to an appropriate mechanism, large numbers of people themselves, without central direction, can divide goods, services and assets up in ways that all consider fair.

The appropriate mechanism here is one in which there is a balance of power, such that no individual can say: "take it or leave it."

This is where Marxism enters. Marxists claim that, under capitalism, the appropriate mechanism is absent. Marx stressed that capitalism was founded upon theft and slavery - what he called primitive accumulation, a process that is still going on. This means that the labour market is an arena in which power is unbalanced: the worker, he said, brings only his own hide to market "and has nothing to expect but ��� a hiding." Exploitation occurs and matters, says (pdf) John Roemer because it is the effect of "an unjust inequality in the distribution of productive assets and resources."

Nor do Marxists expect the state to correct this, because the state is captured by capitalists - it is "a committee for managing the common affairs of the whole bourgeoisie." Marxists smile at the naive centrist utopianism of social democrats who complain about "corporate welfare", because they fail to see that, under capitalism, it could perhaps only rarely be otherwise.

Instead, Marx thought that fairness can only be achieved by abolishing both capitalism and the state - something which is only feasible at a high level of economic development - and replacing it with some forms of decentralized decision-making. There has always been an affinity between Marxism and anarchism, with many Marxists regarding Stalinism as the negation of Marxism.

In this sense, Marxists agree with Andrew: people can find fair allocations themselves without a central agency.

But can they do so under capitalism? One hope that they can lies with trades unions. As Philippe Aghion has pointed out, strong unions are a substitute for minimum wage laws because they ensure a balance of power which facilitates fair labour bargains without state intervention; it's for this reason that Conservatives should in fact support unions.

Herein, I suspect, lie the big differences between Marxists like me and Conservatives like Andrew*. One is: what constitutes a reasonable balance of power? Another is: would a "fair" labour bargain actually be consistent with healthy capitalism, or would it instead lead to a squeeze on profit margins so severe as to deter capital spending and hence depress growth?

* I fear both of these are small groups.

August 13, 2015

Labour's dysfunctional ideology

Imagine you were running a business and were looking to hire someone for a well-paid job that was crucial for your company's success. However, all the applicants for the job seem inadequate and the last two people who did the job were duds who have weakened your company. What do you do?

You could get into fights with your business partners: "your preferred applicant is a twat!" "No; yours is." "If he gets the job, I'm selling my stake."

Or you might try something intelligent. You could change the job spec to make it less demanding, spreading its functions among several employees rather than loading them upon one, probably inadequate, individual.

Of course, I'm not talking about a hypothetical company but the Labour party.

The obvious lesson to draw from the underwhelming leadership contest is that nobody is equipped to be a strong leader and that a more collective and less centralized leadership structure is needed.

This shouldn't be surprising. An effective leader must fulfill numerous functions: influence policy formation; appeal to voters; get the party's organization working adequately; inspire and attract party members; maintain party unity and so on. There's no reason to suppose that one person will be great at all these. As Archie Brown has shown, there are, partly for this reason, strong benefits of more collective political leadership. Labour's most effective government - in 1945-51 - was one in which the leader was only primus inter pares rather than the dominant figure.

But Labour isn't drawing this lesson. Rather than being a technical matter of putting the right people into the right jobs, the leadership election has become a "battle on for the soul of our party" - which is the natural cost of having a winner-take-all election. To invert Kissinger's quip about academia, the politics are so bitter because so much is at stake.

Despite New Labour's belief that politicians should learn from business, the party is behaving in an utterly unbusinesslike way. This is because it has for years been in the grip of the ideology of leadership, a belief that all will be well if only the right leader can be found.

This, though, is pure cargo cult thinking. It fails to ask; through what mechanisms does "leadership" lead to effective outcomes? It equally possible that leadership can be a path to failure - for example by demotivating subordinates; by generating excessive conflict as people view for power; or by entrusting power to someone who ends up living in a purely imaginary world.

But why is Labour trapped by a dsyfunctional faith in leaders? Of course, there are benefits of hierarchy - for example by permitting quick decision-making. But these benefits were not overwhelming in the hands of Brown or Miliband, so why should they become so?

I fear there is a reason - that our media demands strong leaders. It was partly for this reason that the Greens replaced "principle speakers" with a conventional leader - only to find that some of Natalie Bennett's performances showed why they were right in the first place.

However, the demands of a reactionary and dumbed-down media are no justification for bad politics. If we are to have a stronger Labour party - and indeed a healthier society - the ideology of leadership must at least be questioned.

August 11, 2015

The London paradox

How reliable is personal experience? This a question raised by Janan Ganesh in the FT. He writes:

Modern London is liberalism...in excelsis. It has taken the free movement of people, goods, services, capital and ideas to anarchic extremes that might have no precedent.

Anyone can talk a good game about freedom and diversity; living here is a practical test of one���s commitment to these things

I lived in London for over 20 years, and this struck me as nonsense. For one thing, I saw little diversity. I lived in Belsize Park and worked in the FT building, both of which seemed no more ethnically diverse than a Ukip party conference*; some of London's supporters seem to forget that ethnic diversity exists in other cities.

Nor did I experience any "free movement". Perhaps my biggest reason for leaving London was that I wasted hours travelling; one of the biggest adjustments I had to make when I moved to Rutland was realizing that it is quicker and more pleasant to travel the 25 miles into Leicester for an evening than it was to get from the office to the West End.

Like millions of others, I was just a mindless drone moving from silo to silo. The notion of the city as a serendipity engine in which innovation and creativity is sparked by chance meetings always struck me as romantic drivel.

My experience, however, runs into a problem. The fact is that London is far more productive than the rest of the country - 29.2 per cent more so, according to ONS data**. How can this be?

The obvious possibility is that my experience is wrong and cities do indeed benefit (pdf) from agglomeration effects: people learn from living and working alongside each other. As Ed Glaeser has said:

We are a social species that gets smarter by being around other smart people, and that���s why cities thrive. That���s why Wall Street traders still have trading floors where incredibly wealthy people are all willing to sit right on top of each other.

But there's a problem here. If this were the case, we'd expect that cities generally would have higher productivity than less densely populated areas. But in the UK, this is not so. Researchers at the University of Cambridge point out (pdf) that our other major cities such as Birmingham and Manchester have below-average productivity.

This is consistent with another theory - that London's wealth is due not to benevolent agglomeration effects but to parasitism. It might be that big legal (pdf) and financial industries actually depress economic activity elsewhere, in part by sucking talent away from other uses. Professor Glaeser might be right to say that wealthy traders want to sit on top of each other - but this could be because doing allows them to benefit from insider dealing, front-running and rigging markets rather than because of genuine productivity improvements.

I offer this as just a hypothesis. To reject it one must answer the question: why is it that London is one of our few cities to benefit from agglomeration effects?

* You might reply that this is because I lived and worked in affluent areas - to which I reply that the richer parts of Leicester, for example, have a large Asian population.

** This raises another paradox. Higher productivity doesn't translate into higher subjective well-being: Londoners are actually slightly less happy than the national average.

August 10, 2015

Ambiguity aversion in politics

There's a link between David Cameron's holiday snaps and the moral panic about migrants. The link is ambiguity aversion.

We've known ever since Daniel Ellsberg's famous experiments that people don't like ambiguity or uncertainty; they much prefer known probabilities to unknown ones.

This is well known in financial markets: "markets hate uncertainty" is a cliche because its true. However, uncertainty aversion matters in politics too - a fact which is, I fear, under-appreciated.

Here are some examples:

- People fear immigration because it creates uncertainty: they are disquieted by the prospect that migrants will change their communities.The strong possibility that these changes will be benign is little comfort.

- Terrorism is effective - in the sense of provoking a repressive backlash - because it creates uncertainty. The facts might show that Americans are more likely to be killed by policemen than by terrorists - but this doesn't matter because policemen are familiar and so cozy whereas terrorists are not.

- Both front-runners in the Labour leadership election are trying to offer Labour members familiarity: Andy Burnham talks of coming from outside the Westminster Bubble whilst Jeremy Corbyn offers policies which are as warmly nostalgic as Subbuteo and Thunderbirds.

- In talking of Jeremy Corbyn's support for nationalization, Peter Kellner says:

If people think he's doing it as a left-wing ideological move it wouldn't be a popular as if, say, David Cameron did it. If David Cameron said "I'm going to take the railways into public ownership" I think people would be dancing in the streets because nobody would accuse him of doing it for a left-wing ideological motive.

What he's getting at here is that the framing of policies matter. "Left-wing ideology" is unpopular because it seems unfamiliar and so creates uncertainty. Other motives - be they pragmatism or vote-grubbing - are more familiar and hence more acceptable; psychologists call this the mere exposure effect. This is how the Overton window works; policies that are outside the window and so rarely discussed appear to be uncertain and thus become unpopular.

- Radio 4's Broadcasting House asked yesterday whether Ted Heath could become PM now - the point being that a single man would now be seen as strange and hence uncertain. It's for this reason that the media presented Ed Miliband as "weird"; they knew instinctively that the unfamiliar is bad. It's in this context that we should regard Cameron's holiday photo. The message is: "Look, I'm a normal, married guy - you can trust me."

And here's the thing. Some politicians are good at exploiting ambiguity aversion for partisan gains: they know to present themselves as regular guys and their opponents as weirdos.

But this is not the only way in which politicians should address the public's aversion to uncertainty. One function of the political sphere should be to provide institutions which help us to cope with uncertainty: a welfare state which cushions us from economic risks; public services which are flexible enough to deal with social change; an educational system and media which help us understand uncertainties. And so on. But it is not clear that these functions are being fulfilled. Aversion to uncertainty, it seems, is something to be exploited for partisan gain rather than addressed as a political problem.

Another thing: it's easy to forget that Ted Heath became Tory leader in part because he offered familiarity. In the early 60s, the upper-class were regarded as out of touch toffs, as exemplified by Mervyn Griffith-Jones question about Lady Chatterley's Lover: "is this a book you would wish your wife or servants to read?" In this context, the grammar school-educated Heath appealed to those wanting "normality".

Chris Dillow's Blog

- Chris Dillow's profile

- 2 followers